Abstract

Objectives

The Heart Manual (HM) is the UK’s leading facilitated home-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programme for individuals recovering from myocardial infarction and revascularisation. This audit explored patient-reported outcomes of home-based CR in relation to current Scottish, UK and European guidelines.

Setting

Patients across the UK returned their questionnaire after completing the HM programme to the HM Department (NHS Lothian).

Participants

Qualitative data from 457 questionnaires returned between 2011 and 2018 were included for thematic analysis. Seven themes were identified from the guidelines. This guided initial deductive coding and provided the basis for inductive subthemes to emerge.

Results

Themes included: (1) health behaviour change and modifiable risk reduction, (2) psychosocial support, (3) education, (4) social support, (5) medical risk management, (6) vocational rehabilitation and (7) long-term strategies and maintenance. Both (1) and (2) were reported as having the greatest impact on patients' daily lives. Subthemes for (1) included: guidance, engagement, awareness, consequences, attitude, no change and motivation. Psychosocial support comprised: stress management, pacing, relaxation, increased self-efficacy, validation, mental health and self-perception. This was followed by (3) and (4). Patients less frequently referred to (5), (6) and (7). Additional themes highlighted the impact of the HM programme and that patients attributed the greatest impact to a combination of all the above themes.

Conclusions

This audit highlighted the HM as comprehensive and inclusive of key elements proposed by Scottish, UK and EU guidelines. Patients reported this had a profound impact on their daily lives and proved advantageous for CR.

Keywords: home-based, cardiac rehabilitation, patient reported outcomes, guidelines, evidenced based, patient experience

Strengths and limitations of this study.

By using audit data, this qualitative project provides a substantial illustration of patient-reported outcomes of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation programme in relation to current guidelines.

Due to the design of the questionnaire, demographic information of the patients was not gathered.

Conversely, by not gathering demographic information, patients had complete anonymity that the authors agreed may have reduced bias and/or social desirability.

The framework approach provided a systematic approach that accommodated both inductive and deductive thematic analysis. This proved beneficial for managing a large sample of qualitative responses.

Due to the complexities of the HM programme, the findings of this audit may not be generalisable to other home-based cardiac rehabilitation programmes.

Introduction

With over 90% of individuals surviving at least 30 days following their first myocardial infarction (MI), the need for cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is greater than ever before.1 CR programmes are offered to individuals to support recovery and aid secondary rehabilitation. These services within the UK are currently informed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),2 European Society of Cardiology (ESC),3 the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR)4 and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN).5 Key components of these guidelines support the inclusion of information on diagnosis, advice on lifestyle and medical risk management, and psychosocial well-being. As one of the most clinically and cost-effective therapeutic interventions in cardiovascular disease management,6 7 CR is well established within the UK.8 Recent figures have highlighted that the UK has internationally leading levels of uptake, despite still falling short of national recommendations.8 Current evidence suggests that perceived barriers to traditional, centre-based CR may include practical barriers, personal or programme factors.9 Therefore, the future of CR requires flexible delivery and personalisation of care,6 while being mindful of organisational and financial constraints. Alternative forms of CR delivery, such as home-based rehabilitation programmes, are promoted throughout all the current guidelines2–5 and have proved cost-effective10 yet remain an underused mode of delivery.8 One such example highlighted in the guidelines2 8 and successfully embedded across the UK National Health Service and internationally is the Heart Manual (HM; NHS Lothian).11 An individually tailored 6-week CR programme for patients recovering from acute MI and/or revascularisation, the HM is available in either paper or digital format12 and proven to be as cost-effective as traditional centre-based programmes.7 As a flexible resource, the HM has been successfully implemented in CR pathways as both a standalone resource and in collaboration with multidisciplinary teams within centre-based programmes. Founded on cognitive behavioural principles, it provides patients with a tailored approach to promote self-management and well-being. As a guided programme, the HM addresses cardiac misconceptions and enables individuals to use effective coping strategies and techniques throughout their recovery. In the past 26 years, the HM remains highly evidenced and the subject of three randomised controlled trials.13–15 These studies have highlighted significant improvements in psychological outcomes, physical activity, diet, cholesterol and smoking. Furthermore, the resource has been evidenced as improving patients’ quality of life, reducing unplanned hospital and GP healthcare usage and improving accessibility to CR. It has provided the basis for recent developments, including the development of a digital resource and adapted for other conditions such as cancer,16 stroke17 and heart failure.18 19

Evidenced-based CR guidelines regularly inform what is provided to patients, but what remains relatively unexplored at present are patient perspectives about which components of CR they perceive have the greatest impact on their recovery. This audit aims to explore patient-reported outcomes of the impact of the HM programme in relation to the key recommendations published by NICE,2 ESC,3 SIGN4 and BACPR.5

Methods

Patient and public involvement statement

As part of its ongoing quality assurance audit, the HM department regularly receives patient’s feedback via questionnaires from individuals who have experienced the programme. In addition, the Public Involvement Heart Manual Group is a body of patients and healthcare professionals that regularly informs the development of the HM programme and its evaluation process. A summary will be made publicly available on the HM website, as no identifying details of the patients were gathered, meaning patients cannot be informed directly.

Design

This study audited questionnaires returned to the Heart Manual Department by individuals UK wide who had previously been prescribed the resource by a qualified healthcare professional and trained HM facilitator. The decision to prescribe the programme is based on the facilitator’s clinical judgement, with patient safety being paramount alongside other considerations (eg, communication barriers, literacy levels and catchment area). The HM is designed for those with a literacy level of age 9 years and is unsuitable for patients who have a very poor prognosis (cardiac or other) or those with unstable conditions.

Ethics

The Integrated Research Application System responded that this project was not considered research and therefore did not need formal NHS ethical approval, as this project was classified as an audit and ongoing quality assessment of the programme.

Participants

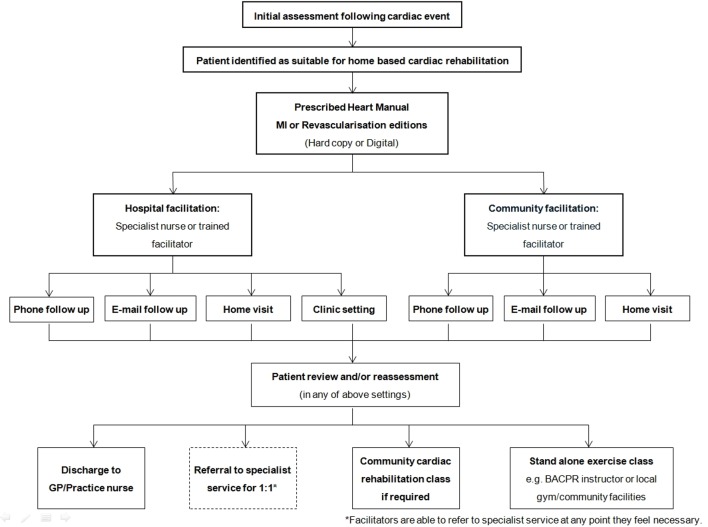

The questionnaire was not designed to gather demographic information of patients. Although this may have offered a greater insight into the impact of the HM, the authors agree that anonymity may have helped reduce bias or social desirability, respectively. Patients were assessed before receiving the HM programmes by a trained HM facilitator (see figure 1 for an overview of the facilitation procedure). Due to the nature of the programme, it is assumed that all patients will have experienced a cardiac event such as MI and revascularisation procedures (eg, angioplasty or coronary artery bypass graft).

Figure 1.

Facilitation procedure of the Heart Manual programme. (BACPR, British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; GP, general practitioner; MI, myocardial infarction.

Procedure

Once patients have worked through the resource, they have the option to return the questionnaire to the HM Department. Patients are informed that the purpose of the questionnaire was to inform future development, quality improvement and audit purposes and that their responses would remain anonymous. Once received, this is transcribed and stored securely on an electronic database. For the purpose of this audit, all available questionnaires that had been returned between November 2011 and January 2018 were included for analysis.

Measures

The HM patient questionnaire comprises three parts. First, it gathers information about the use of the manual and levels of facilitation received. Second, patient’s satisfaction of quality is measured across 23 items that cover the key elements of the programme on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The third section includes four questions where patients are able to provide written responses to what do you think has changed in your day-to-day life since completing the programme, is there anything you would like to see added, what sections do you think have been most useful and any other comments about the HM. For the purpose of this audit, responses from the third section from both the MI and revascularisation editions were included for analysis.

Analysis

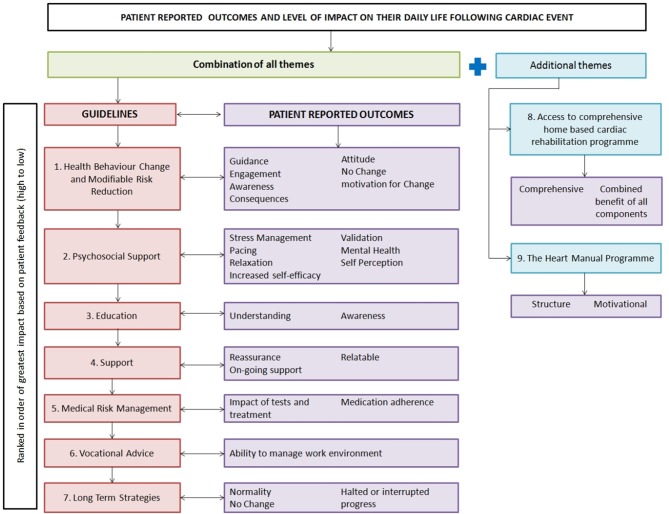

The analysis was an iterative process led by HR (MSc and BSc) who is employed as an assistant psychologist, supported by frequent discussion of emerging themes with CD (Health Psychologist DPsych, MSc and MA (Hons)). Both researchers CD and LT (who have experience in qualitative research and conducting audits) oversaw the audit including initial design of questionnaire and data collection/entry. Analysis was guided by the framework method20 as it allowed combined deductive and inductive thematic analysis. Deriving from social policy research, this approach has been increasingly used in healthcare research.20 The systematic nature of the methodology ensures that analysis is both rigorous and transparent. The framework provided a clear and coherent approach that was preferable given the large number of data sets included in this audit that amounted to 457 questionnaires, which in total amassed to 12,812 words. This approach used structured topic guides to identify patterns within the data. Initial analysis began by coding the transcribed data into the common components in CR guidelines while allowing additional themes to be captured. Secondary analysis used an inductive approach allowing patient reported outcomes to emerge. Findings were interpreted and written up. Figure 2 highlights a visual representation of this process. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research reporting guidelines21 were used and can be found in online supplementary appendix 1.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of the analysis.

bmjopen-2018-024499supp001.pdf (166KB, pdf)

Results

Initial coding combined the key constructs from the guidelines into deductive themes. These were health behaviour change (HBC) and modifiable risk reduction, psychosocial support, education, support, medical risk management, vocational rehabilitation and long-term maintenance. Additional themes that emerged highlighted the importance of access to a comprehensive CR programme and the HM programme. Representative quotes for these themes and relevant subthemes are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Representative quotes of themes

| Theme | |

| Subtheme | Representative quote (Q) |

| 1. Health behaviour change/modifiable risk reduction | |

| Guidance | Q1 ‘What to do to tackle being overweight’. |

| Q2 ‘The risk factors and how to beat it’. | |

| Q3 ‘Ways to include regular exercise in my day’. | |

| Q4 ‘Exercise description and reason given for the exercise gave me incentive to continue in the early days’. | |

| Q5 ‘What to eat’. | |

| Engaging | Q6 ‘More exercise and healthier eating habits’. |

| Q7 ‘Regular daily exercise and routine has certainly increased my fitness and recovery levels’. | |

| Q8 ‘Stopping smoking’. | |

| Q9 ‘I’ve stopped smoking, I’m eating better and I’m doing more exercise especially walking’. | |

| Q10 ‘I’ve lost some weight but not a lot else. I was already very active with a vegan diet. Non smoker/drinker etc’. | |

| Awareness | Q11 ‘More aware of the importance of lifestyle consideration’. |

| Q12 ‘A much livelier awareness of the importance of a healthier diet’. | |

| Q13 ‘Awareness of food labelling. Awareness of the need to practise relaxation’. | |

| Q14 ‘The awareness of need to maintain regular exercise. Also to pay more attention to diet’. | |

| Q15 ‘Consciously thinking about reducing risk factors’. | |

| Q16 ‘More aware of things to do on a daily basis for example, walking and exercising especially and to pace myself’. | |

| Consequences | Q17 ‘I am more energetic and far more active’. |

| Q18 ‘I am more relaxed and have lost weight’. | |

| Q19 ‘General health has improved. Walking more’. | |

| Q20 ‘Restored my love for exercise. Closer to wife with walks taken together and chance to talk openly. Careful with food. Positive lost over 1.5 stone so far!’. | |

| Q21 ‘Restricted my hobbies’. | |

| Q22 “As a racing cyclist I will miss the racing and training, just going out for fun won’t be the same. I will still go out to keep fit’. | |

| Attitude | Q23 ‘Change of attitude to exercise, diet and lifestyle’. |

| Q24 ‘My whole outlook on my lifestyle - that is, how to exercise properly, how and what to eat, that will help me to recover’. | |

| Q25 ‘I now have a determination to put general health issues before anything else, when you feel well everything in life is more enjoyable’. | |

| Q26 ‘Contentment - how to care for your body. How to enjoy life, and to understand life in general’. | |

| Q27 ‘Appreciate life more’. | |

| No change | Q28 ‘Nothing much - I am still a carer for my husband who is permanently in a wheelchair and has cancer. I feel much better walking everywhere without pain in stomach and chest’. |

| Q29 ‘No great change - always had healthy lifestyle’. | |

| Motivation For change | Q30 ‘More committed to healthier lifestyle’. |

| Q31 ‘The incentive to get walking and exercising’. | |

| 2. Psychosocial support | |

| Stress management | Q32 ‘Learning about controlling stress was very very good. I do not worry about things any more, and this makes my life a lot happier’. |

| Q33 ‘More assertive about prioritising my needs. Accepting help from others/realising I cannot (will not) do as I did’. | |

| Q34 ‘I don’t smoke or drink. I have had a lot of stress at work and family history with heart disease so the reduction of stress/relaxation has been very helpful’. | |

| Q35 ‘Sections on stress and anxiety’. | |

| Pacing | Q36 ‘I was very active for a 76 year old. Now I take life a little slower. I do just as much but over a longer period’. |

| Q37 ‘Considering some activities prior to acting as to their benefits etc.’. | |

| Q38 ‘I think I have learnt to listen to my body and not rush things!’ | |

| Q39 ‘To try pace myself and to admit when in trouble’. | |

| Relaxation | Q40 ‘Relaxation… I have devised my own breathing and visualisation which I try to do daily’. |

| Q41 ‘Listen to relaxation CD every day. Sleeping better at nights’. | |

| Q42 ‘More relaxed, eating a better diet, a new lease of life to look forward to’. | |

| Q43 ‘I have slowed down the mad pace in which I used to do everything and am more laid back and relaxed’. | |

| Increased self-efficacy | Q44 ‘I do short walks alone: I used to wait to arrange with friends. I now do some exercises at home’. |

| Q45 ‘Explanation about the condition and the psychological approaches to the problem and the reassurances’. | |

| Q46 ‘Less likely to worry about my condition’. | |

| Q47 ‘I am more prepared to push myself without expecting angina pain’. | |

| Q48 ‘My confidence has improved and I am getting stronger each day’. | |

| Validation | Q49 ‘Completing the programme has re-affirmed the things I already did as being correct’. |

| Mental health | Q50 ‘Turning negative thoughts to positive ones!’ |

| Q51 ‘Low spirits after a heart procedure (depression)’. | |

| Q52 ‘Mostly about operation and recovery and help for couples to cope with mood swings’. | |

| Q53 ‘Angina, stress and anxiety’. | |

| Self-perception | Q54 ‘I have become more tolerant of myself’. |

| Q55 ‘I feel more hopeful than I did prior to completing the programme. Each day I feel I am making progress with small tasks around the house, and this gives me a feeling of worth once again’. | |

| Q56 ‘I found it hard to accept I had a heart attack. Previous to it I had been feeling good. The programme has helped me to realise I had a heart problem’. | |

| Q57 ‘I now accept that I have to change my lifestyle to my condition’. | |

| 3. Education | |

| Understanding | Q58 ‘Learning to understand my health issues and dealing with them’. |

| Q59 ‘What the risk factors are and how to reduce them to prevent other heart attacks’. | |

| Q60 ‘Knowing the truth. So simple but so useful’. | |

| Q61 ‘Understanding the process of recovery’. | |

| Q62 ‘Explaining what uses tablets are for and explaining about stents’. | |

| Q63 ‘Recovery section, exercises section and different ways to deal with emotions after bypass’. | |

| Awareness | Q64 ‘Made me fully aware of the seriousness of my heart attack’. |

| Q65 ‘I am more aware of the workings of the heart, what food is good for me, what is bad’. | |

| Q66 ‘More aware of condition and the treatment’. | |

| 4. Support | |

| Q67 ‘Back to normal. Reassured about recovery process’. | |

| Q68 ‘If I forget I can look it up in your Heart Manual. Plus other advice’. | |

| Q69 ‘Reading the manual knowing it is there to check any time I feel insecure’. | |

| Q70 ‘The stories about how other people feel because one gets the same feelings and I find that the stories have helped me to cope better’. | |

| 5. Medical risk management | |

| Q71 ‘Hospital tests and treatments.’ | |

| Q72 ‘At 82 it is difficult to change lifestyle - but the stent has improved me 100%. Still have some aches and pains - a result of old age?!’ | |

| Q73 ‘I had never taken a pill. I have now’. | |

| Q74 ‘Awareness and control of behaviour. Difficulty in managing medicine regime’. | |

| 6. Vocational support | |

| Q75 ‘Take breaks when go back to work’. | |

| Q76 ‘Reduced time at work’. | |

| Q77 ‘It is just over a year since my heart attack. I am back to normal doing a full time job’. | |

| Q78 ‘I have handed in my notice at work’. | |

| 7. Long-term maintenance | |

| Normality | Q79 ‘Early days but trying to get back normal as what I used to do but it is taking time’. |

| Q80 ‘Not a lot other than getting back to life as it was up to a few weeks before the heart attack but some changes in diet’. | |

| Halted or interrupted progress | Q81 ‘Contracting severe sciatica approx 6 weeks after heart attack has really been debilitating regarding loss of mobility & pain’. |

| Q82 ‘The programme brought me along very nicely but unfortunately introducing me to Beta-Blockers stopped me in my tracks’. | |

| No change | Q83 ‘Nothing doing what I did before’. |

| Q84 ‘My life is much the same as before - I am 91 so do what I can when I can. I have no home help. As I am 92 this year I think I must have been doing something right! I have enjoyed good health until this happened. I don’t think a lot of the manual applied to me!’ | |

| 8. Access to a comprehensive home-based cardiac rehabilitation programme | |

| Q85 ‘Difficult to specify as book is useful in every section’. | |

| Q86 ‘The whole manual has been most helpful to me’. | |

| Q87 ‘I found all information helpful and informative. It’s really interesting and helped me understand what has happened and what was to come over the weeks’. | |

| Q88 ‘All the sections were useful as one built up another as you progressed through’. | |

| Q89 ‘It was all interesting and informative and good to be able to keep referring as I have a bad memory!’ | |

| Q90 ‘All the sections have added to achieving a steady, effective and sustained recovery’. | |

| 9. The Heart Manual programme | |

| Q91 ‘The weekly programme (week by week)’. | |

| Q92 ‘Having a daily record to reflect back on in particular when I had the odd set back, it made a positive impact’. | |

| Q93 ‘The emphasis on daily action/attention helped me focus on my situation and concentrate on what I needed to do’. | |

| Q94 ‘Routine’. | |

| Q95 ‘The daily exercise records. I have found that using them pushes one into making more effort’. | |

HBC and modifiable risk reduction

Guidance

Patients reported that the HM resource provided them with guidance in relation to HBC and modifiable risk reduction (table 1, quote (Q) 1). These included reference to general risk factors (table 1, Q2) and in particular exercise and diet (table 1, Q3–5).

Engagement

Many patients reported engaging in positive changes such as improving their diet, increasing their levels of exercise and stopping smoking (table 1, Q6–8). Many patients highlighted that they were changing more than one health behaviour (table 1, Q9), while others reported that they were engaged in positive health behaviours prior to their event and subsequently perceived little change to be necessary (table 1, Q10).

Awareness

Some individuals expressed an increased awareness of the importance of adopting healthier behaviours on their recovery (table 1, Q11). In particular individuals focused on their diet, relaxation and daily activity (table 1, Q12–14), as well as highlighting lifestyle and risk factors more generally (table 1, Q15 and Q16).

Consequences

The consequences of HBC and modifiable risk reduction emerged. Positive outcomes included feeling more energetic, weight loss and improvement to their overall well-being (table 1, Q17–19). Patients also reported psychosocial improvements such as improved relationships (table 1, Q20). Some negative consequences were noted, particularly for individuals who felt CR restricted their behaviour or had impacted their enjoyment having been previously engaged in a much higher level of competitive fitness (table 1, Q21 and Q22).

Attitude

Individuals reported a change in attitude towards their lifestyle, suggesting that they had reprioritised the importance of diet and exercise (table 1, Q23–25). Many also reported feeling contentment and appreciation for life (table 1, Q26 and Q27).

No change

For those that reported no change, they attributed this to the demands of caring for a relative and/or already being engaged in a healthy lifestyle prior to their cardiac event (table 1, Q28 and Q29).

Motivation for change

Individuals reported an increase in motivation and commitment to improve their health, which for some prompted them to engage in exercise (table 1, Q30 and Q31).

Psychosocial support

Stress management

The impact of stress management techniques was highlighted (table 1, Q32). Individuals found that it had enabled them to be able to prioritise and delegate (table 1, Q33). The usefulness of coping skills was highlighted, and many individuals found it beneficial for addressing feelings of anxiety too (table 1, Q34 and Q35).

Pacing

Pacing was highlighted as one coping techniques that many individuals found beneficial. Patients reported that they took life slower, took greater consideration of the consequences of activities before engaging in them, learnt to listen to their body and seek help when needed (table 1, Q36–39).

Relaxation

Relaxation was frequently referred to, and patients highlighted that it was easily adopted into their daily routine (table 1, Q40). Patients reported this resulted in positive outcomes such as better sleep quality, diet and change in attitude towards life (table 1, Q41–43). It was noted that relaxation was often referred alongside pacing and stress management.

Increased self-efficacy

Patients reported that they felt more capable at performing certain behaviours, specifically physical activity (table 1, Q44). Many found that they felt more reassured and less likely to worry (table 1, Q45 and Q46). This had a positive impact on their recovery, as individuals felt that they were able to challenge themselves physically and as a result had better physical health (table 1, Q47 and Q48).

Validation

For some, it was important that the HM programme confirmed behaviours that they were already engaged in as being correct, positive and in line with current evidence (table 1, Q49).

Mental health

The HM enabled individuals to cope with negative thoughts and feelings of anxiety and depression, which was an important element for patients and their family during recovery (table 1, Q50–52). Patients highlighted that this was closely linked to stress and related conditions such as angina (table 1, Q53).

Self-perception

Importantly, patients noted that after completing the HM programme they had a more positive perception of themselves and their self-worth (table 1, Q54 and Q55). This included helping them to accept having experienced a cardiac event, although it is unclear if misconceptions remain. This may have enabled them to actively engage in reducing their risk factors (table 1, Q56 and Q57).

Education

Understanding

Individuals reported a greater understanding of their condition and potential risk factors since completing the programme (table 1, Q58 and Q59). Many found that the programme increased their understanding by addressing misconceptions and managing their expectations of recovery (table 1, Q60 and Q61). Medication, exercise and coping strategies were frequently referred as an area in which patients felt their knowledge had improved (table 1, Q62 and Q63).

Awareness

Individuals found they had an increased awareness of the seriousness of their event, the biological causes of the event, their treatment and condition in general (table 1, Q64–Q66). Many reported that they had a better awareness of the impact of their diet as a risk factor (table 1, Q65).

Support

Many found the HM programme offered reassurance (table 1, Q67). It was noted that this support was ongoing, and they were able to refer back to the manual at any point they felt they needed to (table 1, Q68 and Q69). In particular, individuals found the scenarios to be reassuring and in line with their own emotions (table 1, Q70).

Medical risk management

Individuals reported the impact of the tests and treatments while in hospital, as well as the surgical event following their cardiac event (table 1, Q71 and Q72). Medication adherence was highlighted with some individuals finding it difficult while others had incorporated it into their daily routine (table 1, Q73 and Q74).

Vocational advice

Patients reported that the vocational advice in the HM programme had enabled them to modify their work to include breaks or reduce their hours (table 1, Q75 and Q76). Some felt able to return to work once they had recovered, while some felt it was not possible (table 1, Q77 and Q78).

Long-term maintenance

Normality

Individuals highlighted that they wanted a sense of normality and for their lives to be as they were before their event (table 1, Q79). Some individuals noted that there had been some positive long-term changes to their diet (table 1, Q80).

Halted or interrupted progress

Some individuals noted that their progress had been stopped or interrupted by other conditions and comorbidities that had made it difficult to engage in CR (table 1, Q81 and Q82).

No change

For the few individuals who highlighted that they did not engage in HBC, this may have been because they felt they had little modifiable risk factors to reduce or they felt that certain aspects of the HM manual was not entirely applicable to them (table 1, Q83 and Q84).

Additional themes that emerged included:

Access to a comprehensive CR programme

The majority of individuals agreed that having access to a comprehensive self-management programme was necessary for their recovery as they benefited from many of the elements included in the HM (table 1, Q85–88). This had a profound effect on throughout their recovery and secondary prevention (table 1, Q89 and Q90).

The HM programme

Overall, the HM resource was positively received by patients. In particular, patients reported that the presentation of the manual and the weekly structure had made a positive impact (table 1, Q91 and Q92). Individuals found this helped reflection, prioritise daily tasks and enable routine and motivation (table 1, Q93–95).

Discussion

Patients reported that above all a comprehensive and holistic approach to CR, which addressed biopsychosocial elements, had the greatest impact on their recovery. In particular, the findings of this audit highlighted that patients perceived HBC, modifiable risk reduction and psychosocial support to have the greatest impact on recovery as singular components. HBC and modifiable risk reduction were grouped as patient feedback highlighted a significant level of overlap between the two components. Guidance was reported alongside increased levels of engagement, awareness and motivation to change by adopting or modifying their health behaviours, most notably diet and physical activity. The consequences of these behavioural changes were also evident and are comparable with CR programmes across the UK,8 including improvements across biological markers, increased levels of smoking cessation and physical activity. Although patients in this sample did not report outcomes in relation to specific biological markers, this is unsurprising as the questionnaire was designed to elicit more general responses. Encouragingly, the findings of this study highlighted that patients receiving the HM reported positive changes to their weight, despite being reported as one of the more difficult risk factors to address.8 Smoking cessation did not emerge as a subtheme; however, given that the number of patients entering CR as non-smokers is as high as 94%,8 this is unsurprising as fewer patients are requiring this in comparison with other behavioural changes. Some individuals were already engaged in a healthy lifestyle or felt unable to make changes due to competing demands (eg, caregiving). In two cases, patients reported feeling restricted and reduced levels of enjoyment during physical activity, highlighting the need for facilitation and tailoring of CR programmes.

Around 30% of patients will experience some degree of depression and anxiety, of which 20% will develop major depression.22 23 Associated with both of these are detrimental consequences on individual’s recovery and quality of life, as well as increased levels of mortality and morbidity.24 25 Across the UK, CR programmes consistently observe a reduction in the levels of anxiety and depression.8 Comparably, patients reported that the HM had a profound effect on their mental health and helped them to manage negative thoughts and feelings of anxiety and depression, consistent with previous literature.13–15 Patients felt less stressed and increasingly able to effectively pace themselves and relax. Other factors that can negatively impact quality of life post cardiac event include sexual health, alcohol/substance abuse, illness misconceptions and low levels of self-efficacy.4 Although individuals in this sample did not refer to sexual health or alcohol/substance abuse, positive changes to individual’s self-perception and improvement in self-efficacy was evident.

CR programmes are encouraged to provide education on medication, stress management, emotional well-being, illness perceptions, health behaviours and long-term maintenance.2–4 Additionally, the BACPR suggests CR should encompass other occupational and vocational factors, sexual health and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.4 The HM programme is highlighted in current national guidelines as an example of best practice for providing health education.2 Patients reported increased levels of understanding and greater awareness, which interplayed heavily with the other themes. It was evident that this contributed and strengthened HBC, modifiable risk reduction and psychosocial support. Patients found misconceptions and expectations of their recovery were addressed, which alleviated anxiety. This increased understanding of their condition and contributory risk factors encouraged them to engage with HBC. Social support is often embedded within the provision of psychosocial support. Literature has highlighted its protective effect for anxiety and depression,26 as well as an effective behaviour change technique.27 Conversely, low social support has been associated with increased mortality rates.28 Patients reported feeling reassured and safe finding the scenarios particularly supportive and understanding of the emotional responses to cardiac events. Patients felt this level of support was reinforced by the ability to retain the HM and use it for ongoing reference as required.

Less frequently referred to were medical risk management, vocational rehabilitation and long-term maintenance, although it was still evident that it was beneficial for some. Throughout the guidelines, medical risk management refers to the reduction of modifiable risk factors through behavioural management and prescribing practice.2–5 In this sample, patients highlighted surgical events, treatments and medication. Patients may perceive this as less demanding compared with other behavioural changes due to a lower level of perceived autonomy. Vocational rehabilitation may not have featured more prominently as home-based options tend to be used by individuals over 75 years, of which the majority are retired.8 For those individuals who did refer to it, they reported feeling able to apply the goal setting and pacing skills that enabled them to feel supported and able to return to work and make suitable modifications. Long-term maintenance features heavily throughout CR guidelines and although it was referred to least, this was unsurprising given that patients were encouraged to return the questionnaire on completion of the 6-week programme and may not have had the opportunity to consider the impact of long-term maintenance of the programme on their daily lives. This is an important area for future research as by completing home-based rehabilitation and incorporating it into their daily lives in a natural setting may have a considerable effect on long term maintenance. Additionally, the HM programme received an overwhelmingly positive response. In particular, the presentation and weekly structure enabled patients to reflect on their progress, self-manage, prioritise daily tasks, become motivated and sustain a routine. Throughout the audit, it was evident that the components of CR are heavily interwoven with one another. As a result, it was unsurprising that patients reported the greatest impact on their recovery was having access to a comprehensive, highly evidenced programme that encompassed the wide range of topics, as proposed by the guidelines.2–5

This audit highlights the importance of considering the patients’ perspective in CR design. By understanding which elements of CR patients perceive have the greatest impact on their recovery, those providing services can be better informed, which may optimise uptake or ensure patients remain engaged throughout. Furthermore, this may help understanding of why CR programmes have an effect and complement studies that have examined programmes efficacy. These findings illustrate the profound effect and beneficial outcomes patients achieve through well-evidenced home-based programmes. It is worth noting that there are many further areas recommended for inclusion within CR programmes, many of which are embedded within the HM resource and supplemented through active facilitation. Further study is needed to explore this.

Trustworthiness and limitations

Due to the design of the patient questionnaire, we cannot claim that this methodology provides a rich account of individual’s experiences. However, by using the framework approach to guide our analysis, it meant that the interpretation of the findings accurately portrayed participants’ responses. Similarly, the credibility of these findings is strengthened by the consistency in patient-reported outcomes throughout the 7-year period in which questionnaires were gathered. It would have been preferable to include a follow-up to see the effect of the HM programme over a longer period; however, due to the design and anonymity of the patient questionnaire, this was not possible. Similarly, demographic details were not gathered and may have provided greater insight. The authors agree that the lack of demographic details ensured patients had total anonymity and may have reduced bias and/or social desirability.

Given the consistency in the patient reported themes and subthemes, it is unlikely that any more would have emerged with the inclusion of a third reviewer at the coding stage. However, a third party familiar with the audit process and guidelines (LT) reviewed the final output of the themes. A further limitation of this audit is that due to the specific nature of the HM programme, these findings are not transferable to other home-based CR programmes. They do however add to our existing knowledge of what patients find has the greatest impact on their recovery and can be used to inform future research.

Conclusion

This audit appears to be the first to explore patient reported outcomes of the UK’s leading home-based CR programme in relation to current guidelines, further evidencing the HM as a validated programme that meets current local, national and European level guidance. These findings provide a substantial, illustrated and previously unexplored account of the outcomes patient’s experience throughout their recovery and secondary prevention after using the HM programme, which has important implications for CR programmes and service providers alike.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients UK wide who took the time to fill out the questionnaire after completing the Heart Manual (HM) programme and returning it to the department in NHS Lothian. In addition, our thanks to Lucie Michalova, Heather Cursiter and Frieda Brookmann for their role in inputting the questionnaire data.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors are involved in the continual development of the HM programme. HR was involved in the audit design, led on the data analysis and interpretation and prepared the manuscript. CD led on the audit, oversaw data collection and was involved in the design of the patient questionnaire, the audit design, data analysis and interpretation and contributed to the manuscript preparation. LT was involved in the design of the patient questionnaire and oversaw data collection, reviewed the final data analysis and interpretation output and contributed to the reviewing and editing of the manuscript. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Integrated Research Application System was used to ascertain whether a formal ethical approval was required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Requests for data sharing can be sent to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. National Services Scotland. Scottish heart disease statistics. Scotland: National Services Scotland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease. Clinical guideline [CG172]. National Institute for Health Care and Excellence, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. The British association for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation. London: The British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. SIGN 150. Cardiac rehabilitation. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network: Edinburgh, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2015;351351:h5000 10.1136/bmj.h5000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shields GE, Wells A, Doherty P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. Heart 2018;104:1403–10. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doherty P. The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Annual statistical report 2017. New york: The British Heart Foundation, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Herber OR, Smith K, White M, et al. ’Just not for me' - contributing factors to nonattendance/noncompletion at phase III cardiac rehabilitation in acute coronary syndrome patients: a qualitative enquiry. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:3529–42. 10.1111/jocn.13722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dalal HM, Zawada A, Jolly K, et al. Home based versus centre based cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:b5631 10.1136/bmj.b5631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Heart Manual Department. The Heart Manual. 11th Impression. Edinburgh: The Heart Manual Department, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deighan C, Michalova L, Pagliari C, et al. The digital Heart Manual: a pilot study of an innovative cardiac rehabilitation programme developed for and with users. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:1598–607. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewin B, Robertson IH, Cay EL, et al. Effects of self-help post-myocardial-infarction rehabilitation on psychological adjustment and use of health services. Lancet 1992;339:1036–40. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90547-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jolly K, Lip GY, Taylor RS, et al. The Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation study (BRUM): a randomised controlled trial comparing home-based with centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Heart 2009;95:36–42. 10.1136/hrt.2007.127209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dalal HM, Evans PH, Campbell JL, et al. Home-based versus hospital-based rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: A randomized trial with preference arms-Cornwall Heart Attack Rehabilitation Management Study (CHARMS). Int J Cardiol 2007;119:202–11. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deighan C, Ranaldi H, Taylor L. “It felt like an arm around my shoulder” – Findings from piloting The Cancer Manual: A comprehensive self-management resource for patients living with and beyond cancer: NHS Lothian, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Heart Manual Department. The Stroke Workbook. Edinburgh: Lothian Health Board, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Greaves CJ, Wingham J, Deighan C, et al. Optimising self-care support for people with heart failure and their caregivers: development of the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH-HF) intervention using intervention mapping. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2 10.1186/s40814-016-0075-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taylor RS, Hayward C, Eyre V, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH-HF) facilitated self-care rehabilitation intervention in heart failure patients and caregivers: rationale and protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009994 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:1–8. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meijer A, Conradi HJ, Bos EH, et al. Adjusted prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: individual patient data meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2013;203:90–102. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.111195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roest AM, Martens EJ, Denollet J, et al. Prognostic association of anxiety post myocardial infarction with mortality and new cardiac events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2010;72:563–9. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dbff97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chauvet-Gélinier JC, Trojak B, Vergès-Patois B, et al. Review on depression and coronary heart disease. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2013;106:103–10. 10.1016/j.acvd.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roest AM, Zuidersma M, de Jonge P. Myocardial infarction and generalised anxiety disorder: 10-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:324–9. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu RT, Hernandez EM, Trout ZM, et al. Depression, social support, and long-term risk for coronary heart disease in a 13-year longitudinal epidemiological study. Psychiatry Res 2017;251:36–40. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heron N, Kee F, Donnelly M, et al. Behaviour change techniques in home-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e747–e757. 10.3399/bjgp16X686617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiss-Faratci N, Lurie I, Neumark Y, et al. Perceived social support at different times after myocardial infarction and long-term mortality risk: a prospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:424–8. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024499supp001.pdf (166KB, pdf)