Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the patient pathways and associated health outcomes, resource use and corresponding costs attributable to managing unhealed surgical wounds in clinical practice, from initial presentation in the community in the UK.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort analysis of the records of 707 patients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database whose wound failed to heal within 4 weeks of their surgery. Patients’ characteristics, wound-related health outcomes and healthcare resource use were quantified, and the total National Health Service (NHS) cost of patient management was estimated at 2015/2016 prices.

Results

Inconsistent terminology was used in describing the wounds. 83% of all wounds healed within 12 months from onset of community management, ranging from 86% to 74% of wounds arising from planned and emergency procedures, respectively. Mean time to healing was 4 months per patient. Patients were predominantly managed in the community by nurses and only around a half of all patients who still had a wound at 3 months were recorded as having had a follow-up visit with their surgeon. Up to 68% of all wounds may have been clinically infected at the time of presentation, and 23% of patients subsequently developed a putative wound infection a mean 4 months after initial presentation. Mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months was £7300 per wound, ranging from £6000 to £13 700 per healed and unhealed wound, respectively. Additionally, the mean NHS cost of managing a wound without any evidence of infection was ~£2000 and the conflated cost of managing a wound with a putative infection ranged from £5000 to £11 200.

Conclusion

Surgeons are unlikely to be fully aware of the problems surrounding unhealed surgical wounds once patients are discharged into the community, due to inconsistent recording in patients’ records coupled with the low rate of follow-up appointments. These findings offer the best evidence available with which to inform policy and budgetary decisions pertaining to managing unhealed surgical wounds in the community.

Keywords: burden, cost, surgical wounds, wound management, surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate the patient pathways and associated health outcomes, resource use and corresponding costs attributable to managing unhealed surgical wounds over 12 months from the onset of community management.

This study was undertaken using real-world evidence derived from the anonymised records of a sample of patients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database (a nationally representative database of clinical practice among >11 million patients registered with general practitioners (GP) in the UK).

The estimates were derived following a systematic analysis of patients’ characteristics, wound-related health outcomes and all community-based and secondary care resource use contained in the patients’ electronic records.

Computerised information in the THIN database is collected by GPs for clinical care purposes and not for research, consequently the accuracy of wound descriptors and other terminology has not been validated, but does reflect real-world documentation in clinical practice.

The analysis does not consider the potential impact of patients’ surgical wounds that heal within 4 weeks of the surgical procedure or those patients who remain in hospital until their surgical wound heals.

Introduction

More than 10 million operations were performed by the National Health Service (NHS) in England1 in 2015/2016, with the majority involving an incision.2 Most incised surgical wounds generally heal by primary intention. However, some heal by secondary intention, either because the wound has intentionally been left open or has dehisced following primary closure.3 4 Surgical wounds healing by secondary intention are thought to be common in the UK, and to account for 26%–28% of all surgical wounds requiring continued nursing intervention.5 Such wounds may remain open for an extended period and are susceptible to infection, requiring ongoing treatment.6 Surgical wound dehiscence (SWD), defined as the rupture or splitting open of a previously closed surgical incision site, may be either superficial or deep.7 Dehisced wounds may be left to heal fully through secondary intention, or closed surgically after partial healing.

The management of patients with an unhealed surgical wound remains challenging because of the potentially high chance of developing further wound complications.8 Such complications can result in hospital readmission, further surgery and prolonged hospitalisation, and may require intensive management in the community. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimated that 5% of all surgical procedures result in a surgical site infection (SSI) in the UK and account for up to 20% of cases of healthcare-associated infections.9 The SSI data collected by hospitals could be an underestimate as most patients develop signs and symptoms after discharge.10

The Burden of Wounds study reported that unhealed surgical wounds accounted for 11% (n=250 000 patients) of all wounds managed in the UK by the NHS in 2012/2013.11 The annual NHS cost attributable to managing these wounds and associated comorbidities was estimated to be £982.9 million.12 After adjustment for comorbidities, the annual NHS cost was estimated to be between £957.4 and £985.8 million.12

Wound management is now of sufficient concern among the wound care community in the UK, that the UK Parliament (House of Lords) debated developing a national strategy for improving the standards of wound care in the NHS.13 All healthcare systems recognise the importance of healing surgical wounds without complications. Nevertheless, there is a lack of information surrounding the characteristics of patients with surgical wounds healing by primary or secondary intention, the time taken for these wounds to heal, wound treatment and patient management within the community. Additionally, the healthcare costs associated with SWD are poorly reported and are frequently conflated with the cost of SSI. This paucity of data limits our understanding of the healthcare needs of patients with an unhealed surgical wound and also hinders the planning and allocation of the relevant resources. The aim of the present analysis was to follow a cohort of patients in clinical practice from initial presentation of their surgical wound in the community, to evaluate in greater depth how managing patients with an unhealed surgical wound impacts on healing and NHS costs.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort analysis of the case records of patients with an unhealed surgical wound (defined as one that had not healed within 4 weeks of the surgical procedure), randomly extracted from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database. The perspective of the analysis was that of the UK’s NHS and the time horizon was 12 months from initial presentation in the community.

THIN database

The THIN database (IMS, London, UK) contains electronic records on > 11 million anonymised patients entered by general practitioners (GPs) from >560 practices across the UK. The patient composition within the THIN database has been shown to be representative of the UK population in terms of demographics and disease distribution,14 and the database theoretically contains patients’ entire medical history, as previously described.11 Hence, the information contained in the THIN database reflects actual clinical practice.

Study population

The authors had previously obtained a random sample of records of 6000 adult patients with a documented history of a wound for whatever reason from the THIN database, for previous wound studies. The study population of 707 patients was identified within this cohort of 6000 patients according to the following criteria:

Were 18 years of age or over.

Had undergone a surgical procedure either during or after 2012.

Had a surgical wound which had remained unhealed for 4 weeks after the surgical procedure.

Had at least 12 months of continuous medical history in their case record from the first mention of their surgical wound unless it healed.

Patients whose wound healed within 4 weeks of their surgical procedure or those with a dermatological tumour were excluded from the data set. Any patients with an unhealed surgical wound who died within a year of initial presentation in the community were also excluded, since the study design was to examine the trajectory of these wounds over a full 12 months from initial presentation unless it healed.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public were not directly involved in this study. The study population was limited to the anonymised records of patients in the THIN database.

Study variables and statistical analyses

Information was systematically extracted from the patients’ electronic records over a period of 12 months from initial presentation of their unhealed surgical wound in the community. This included patients’ characteristics, comorbidities (defined as a non-acute condition that patients were suffering from in the year before the start of their wound), wound-related healthcare resource use (ie, dressings, bandages, topical treatments, negative pressure wound therapy, district nurse visits (who provide care within a patient’s home), practice nurse visits (who provide care within a GP’s surgery), GP visits, hospital outpatient visits, laboratory tests), prescribed medication (ie, analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and systemic anti-infectives (principally antibiotics)) and clinical outcomes (ie, healing and putative infection). If a patient received a bandage or dressing on a specific date, but a clinician visit was not documented in their record, it was assumed the patient had been seen outside of the general practice by a district nurse. No other assumptions were made regarding missing data and there were no other interpolations.

Differences between two subgroups were tested for statistical significance using a Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 test. Differences between three subgroups were tested for statistical significance using a Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2 test. Multivariate logistic regression (using the enter method in which all the independent variables were entered into the analysis simultaneously) investigated relationships between baseline variables and clinical outcomes. Kaplan-Meier analyses were undertaken to compare the healing distribution of different subgroups. The p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant and have been reported. All p values ≥0.05 were not considered to be statistically significant and these numerical values have not been reported. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM UK).

Cost of patient management

Unit costs at 2015/2016 prices15–17 were assigned to the resource use values to estimate the mean NHS cost of managing an unhealed surgical wound over 12 months from initial presentation in the community.

Sensitivity analyses

Deterministic sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess how the cost of managing an unhealed surgical wound changes by varying the values of clinical outcomes and resource use.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

This analysis has essentially studied a cohort of patients with SWD or an open wound left to heal by secondary intention. However, the term dehiscence or open wound was only recorded in 4% of the patients’ case records. The most frequently used terms were ‘dressing of wound’ or ‘dressing of surgical wound’. The age of the study population was a mean of 62.6±17.8 years per patient. Fifty-eight per cent (n=411) of the cohort of patients were >60 years of age, and 26% (n=184) were ≤50 years of age. Seventy-one per cent (n=505) of patients had undergone a planned surgical procedure and 29% (n=202) an emergency procedure. Two-thirds (67%) of all the patients were discharged from hospital into the community within 2 weeks of their surgical procedure; the median length of stay was 10 days. Patients’ baseline characteristics and anatomical site of surgery are summarised in table 1. Twenty-two per cent of all the wounds arose from abdominal surgery, and 14% arose from limb (vascular) surgery of which 79% of the procedures involved either a minor or major amputation.

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline characteristics

| Mean age at time of surgery per patient | 62.6 years |

| Female | 54% |

| Mean systolic blood pressure per patient | 131.0 mm Hg |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure per patient | 75.4 mm Hg |

| Mean BMI per patient | 29.6 kg/m2 |

| BMI<18.5 kg/m2 | 3% |

| BMI≥30.0 kg/m2 | 46% |

| Smokers | 21% |

| Ex-smokers | 29% |

| Non-smokers | 50% |

| Abdominal surgery | 22% |

| Lower limb (vascular) surgery | 14% |

| Minor surgery | 12% |

| Lower limb (orthopaedic) surgery | 10% |

| Upper limb surgery | 9% |

| Skin surgery | 8% |

| Chest surgery | 8% |

| Unspecified surgery | 4% |

| Head and/or neck surgery | 4% |

| Perineal surgery | 3% |

| Lower limb (minor) surgery | 2% |

| Back surgery | 2% |

| Groin surgery | 1% |

BMI, body mass index.

The cohort had a mean of 5.3±2.7 comorbidities per patient, ranging from 5.2±2.7 comorbidities per patient who had a planned surgical procedure to 5.5±2.6 comorbidities per patient who underwent an emergency procedure. These differences were not significantly different. Additionally, 29% (n=205) of all patients had diabetes (27% (n=137) and 34% (n=68) of patients who underwent a planned or emergency procedure, respectively). Patients’ comorbidities are summarised in table 2. There were no significant differences in the incidence of comorbidities between patients whose wound did or did not heal within 12 months from initial presentation in the community (not shown), with the exception that 42% of patients whose wound remained unhealed had diabetes compared with 27% of healed patients; p<0.01.

Table 2.

Patients’ comorbidities

| Comorbidity | Percentage of patients with a comorbidity | ||

| All (%) | Planned procedures (%) | Emergency procedures (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 70 | 69 | 71 |

| Cerebrovascular | 7 | 6 | 9 |

| Dermatological | 54 | 54 | 54 |

| Endocrinological | 48 | 47 | 50 |

| Gastroenterological | 41 | 39 | 45 |

| Genitourinary | 32 | 32 | 30 |

| Haematological | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Hepatological | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Immunological | 13 | 12 | 15 |

| Musculoskeletal | 68 | 67 | 70 |

| Neurological | 27 | 27 | 28 |

| Oncological | 25 | 24 | 27 |

| Ophthalmological | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Otolaryngological | 22 | 20 | 28 |

| Psychiatric | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Renal | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Respiratory | 39 | 37 | 42 |

Clinical outcomes

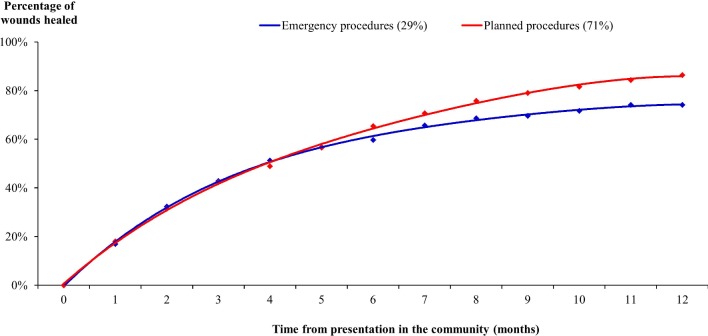

This study was an analysis of unhealed surgical wounds following a documented surgical procedure in the patients’ medical records. The THIN database does not define what a wound is nor does it define wound healing. Wound healing was a clinical observation not necessarily confirmed by a specialist and it is unknown if the nurses/GPs who managed these patients used any consistent definition. On that basis, 83% (n=607) of all the wounds in this study’s cohort were estimated to have healed within 12 months from initial presentation in the community (figure 1), with healing ranging from 86% of wounds arising from a planned procedure to 74% of wounds arising from an emergency procedure. The time to healing was a mean of 4.2±3.0 months per patient. However, this ranged from a mean of 3.9±3.0 months for patients who had undergone planned surgery to 4.3±2.8 months for those who had undergone an emergency procedure.

Figure 1.

Wound healing stratified by planned/emergency procedures.

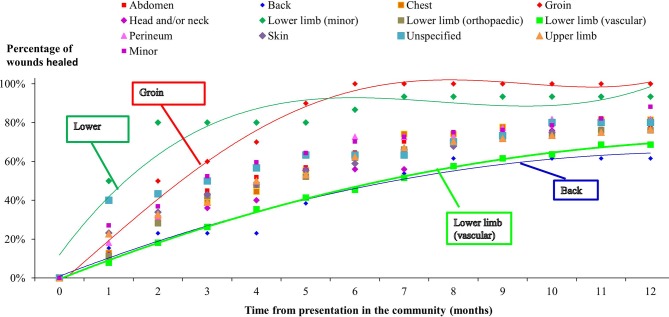

The distribution of healing between the wounds arising from planned and emergency procedures was not significantly different (p=0.26 from a Kaplan-Meier analysis). The healing rates stratified by anatomical site of surgery are shown in figure 2. All the groin procedures healed, 93% of the minor lower limb procedures healed and 88% of the other minor procedures healed within 12 months from initial presentation in the community. Conversely, only 62% of back procedures and 69% of vascular lower limb procedures healed during this period. Irrespective of the other anatomical sites of surgery, between 76% and 82% of all the other procedures healed within 12 months from initial presentation in the community.

Figure 2.

Wound healing stratified by anatomical site of surgery.

Healing appeared to be affected by a patient’s body mass index (BMI). Ninety-four per cent of patients with a BMI <20 kg/m2 healed during the study period compared with 89% of patients with a BMI of 20–29 kg/m2, 84% of those with a BMI of 30–35 kg/m2 and 84% of those with a BMI of >35 kg/m2. None of these rates were significantly different, although there was a trend. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the BMI of those patients who underwent planned or emergency procedures. Additionally, significantly more wounds of patients without diabetes healed over the 12 months’ follow-up period compared with patients who had diabetes (88% vs 80%; p=0.002).

Binary logistic regression showed that within the limitations of the data documented in the records, anatomical site of surgery, having diabetes, having a suspected infection (see ‘Infection’ in the Results section) and undergoing an emergency procedure are potential independent risk factors for a wound not healing:

Suspect infection: OR 0.497 (95% CI 0.223 to 0.935); p=0.032.

Lower limb (vascular) surgery: OR 0.538 (95% CI 0.310 to 0.934); p=0.028.

Diabetes: OR 0.546 (95% CI 0.301 to 0.903); p=0.007.

Emergency surgery: OR 0.660 (95% CI 0.408 to 0.990); p=0.045.

Smoking was not identified as being an independent risk factor for non-healing; 50% of patients in both the healed and unhealed groups were smokers or ex-smokers at the time of surgery.

Patient management

At the onset of their wound management in the community, 46% of patients were prescribed an absorbent dressing, 39% an antimicrobial dressing, 39% a soft polymer, 36% a foam, 32% an alginate, 32% a permeable dressing, 29% a hydrocolloid and 24% a hydrogel (table 3). Dressing use for the initial treatment was unaffected by whether a patient had undergone a planned or emergency procedure.

Table 3.

Dressings prescribed at the time of initial presentation in the community

| Percentage of patients who were treated with the following dressings for their initial treatment | |||||||||||

| Absorbent (%) | Alginate (%) | Antimicrobial (%) | Foam (%) | Hydrocolloid (%) | Hydrogel (%) | Low adherence (%) | Odour absorbent (%) | Other (%) | Permeable (%) | Soft polymer (%) | |

| All | 46 | 32 | 39 | 36 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 37 | 32 | 39 |

| Emergencies | 46 | 34 | 39 | 38 | 32 | 26 | 27 | 0 | 37 | 32 | 41 |

| Planned | 46 | 30 | 39 | 36 | 29 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 37 | 32 | 39 |

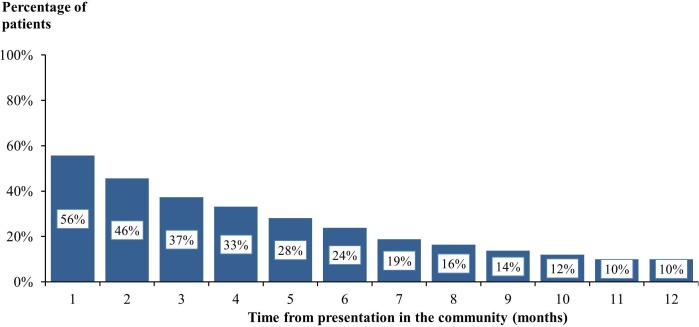

Patients continued to be prescribed their initial mix of dressings until such time as their wound healed (table 4). Over half of the patients received multiple dressings at each dressing change in the first month of treatment, decreasing to 10% of patients by the 12th month of treatment (figure 3). Patients who were treated with multiple dressings received between a mean of 2 and 4 dressings. Overall, patients’ dressings were changed three times a week. Additionally, <1% of patients who had undergone a planned procedure and 2% of those who had undergone an emergency procedure received negative pressure wound therapy.

Table 4.

Dressings prescribed over the 12 months following initial presentation in the community

| Month of treatment | Percentage of patients who were treated with the following dressing | ||||||||||

| Absorbent (%) | Soft polymer (%) | Antimicrobial (%) | Other (%) | Foam (%) | Permeable (%) | Alginate (%) | Hydrocolloid (%) | Low adherence (%) | Hydrogel (%) | Odour absorbent (%) | |

| 1 | 46 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 0 |

| 2 | 38 | 35 | 35 | 32 | 13 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 24 | 25 | 0 |

| 3 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 28 | 32 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 24 | 21 |

| 4 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 26 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 21 | 22 | 0 |

| 5 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 26 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 0 |

| 6 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| 7 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 18 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 0 |

| 8 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 9 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 0 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| 11 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 17 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| 12 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 0 |

Figure 3.

Patients who received a combination of multiple dressings at each dressing change.

In addition to dressings and bandages, 42% of patients were prescribed an analgesic or NSAID, and 36% were prescribed a systemic anti-infective at the time of initial presentation in the community. Over the study period, 66% of all patients were prescribed an anti-infective and 59% of all patients received an antimicrobial dressing.

Healthcare resource use associated with managing an unhealed surgical wound in the community is shown in table 5. Patients were predominantly managed in the community by nurses. Only three patients were documented as having had a single visit by a tissue viability nurse. Two of these patients had undergone a planned procedure and one an emergency procedure.

Table 5.

Healthcare resource use associated with managing unhealed surgical wounds in clinical practice

| Resource use | Mean amount of resource use per patient over 12 months from initial presentation | ||

| All | Planned procedures | Emergency procedures | |

| Bandages | 18.88 | 19.10 | 18.30 |

| District nurse visits | 72.00 | 73.10 | 69.20 |

| Dressings | 177.50 | 182.50 | 164.50 |

| GP visits | 2.80 | 2.90 | 2.50 |

| Hospital admissions | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.39 |

| Hospital outpatient visits | 2.20 | 2.10 | 2.50 |

| Laboratory tests | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.75 |

| Negative pressure wound therapy | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| Practice nurse visits | 10.30 | 10.80 | 9.20 |

| Prescriptions for analgesic and non-steroidal inflammatories | 5.60 | 5.80 | 5.20 |

| Prescriptions for anti-infectives | 2.40 | 2.40 | 2.20 |

| Topical treatments | 3.30 | 2.10 | 6.20 |

GP, general practitioner.

Fifty-nine per cent of all patients were recorded as having had a follow-up visit with their surgeon within 3 months from discharge into the community, ranging from 54% of patients who had undergone a planned procedure to 66% of those who had undergone an emergency procedure. Fifty-eight per cent of all patients (58% and 57% of those who had undergone a planned or emergency procedure, respectively) still had a wound at 3 months and only 53% of them had a follow-up visit with their surgeon. Additionally, 39% of all patients (38% and 40% of those who had undergone a planned or emergency procedure, respectively) still had a wound at 6 months and only 40% of them had a follow-up visit with their surgeon. Furthermore, 19% of patients were readmitted into hospital a mean of 3.6 months after original discharge, including 9% within 30 days of discharge.

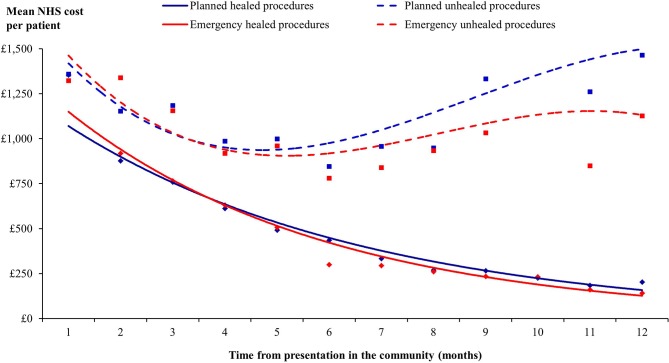

Cost of patient management

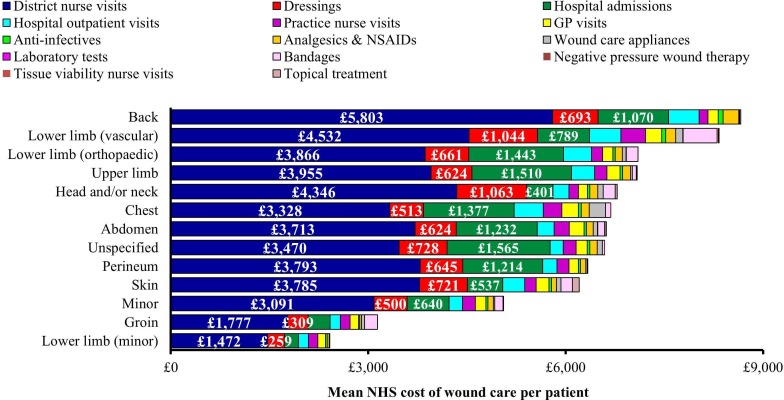

The mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months, following initial presentation in the community, was an estimated £7345±£6673 per surgical wound, ranging from a mean of £7163±£6366 to £7800±£6405 per wound that arose following a planned or emergency procedure, respectively (table 6). Figure 4 illustrates the monthly cost of managing these wounds, and shows how the monthly wound management cost starts to increase around month 5/6 if the wound fails to heal. The mean NHS cost of wound care of managing a wound that remained unhealed was at least double that of managing a wound that healed (mean of £5997 vs £13 682 per unhealed surgical wound) (table 7). The mean NHS cost of wound care stratified by anatomical site of surgery is shown in figure 5.

Table 6.

Cost of healthcare resource use associated with managing unhealed surgical wounds in clinical practice (percentage of total cost is in parenthesis)

| Resource | Mean cost of resource use per patient over 12 months from initial presentation in the community | |||||

| All procedures (%) | Planned procedures (%) | Emergency procedures (%) | ||||

| District nurse visits | £4186.81 | (57) | £4142.62 | (58) | £4297.30 | (55) |

| Hospital admissions | £1086.76 | (16) | £972.30 | (14) | £1372.91 | (18) |

| Dressings | £763.73 | (10) | £772.50 | (11) | £741.82 | (10) |

| Hospital outpatient visits | £348.55 | (5) | £326.04 | (5) | £404.84 | (5) |

| Practice nurse visits | £253.29 | (3) | £262.33 | (4) | £230.69 | (3) |

| GP visits | £219.33 | (3) | £227.02 | (3) | £200.11 | (3) |

| Bandages | £214.65 | (3) | £202.20 | (3) | £245.77 | (3) |

| Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories | £118.42 | (2) | £118.31 | (2) | £118.68 | (2) |

| Wound care appliances | £83.61 | (1) | £75.35 | (1) | £104.24 | (1) |

| Anti-infectives | £43.44 | (1) | £43.51 | (1) | £43.26 | (1) |

| Topical treatments | £17.17 | (<1) | £12.35 | (<1) | £29.22 | (<1) |

| Negative pressure wound therapy | £6.00 | (<1) | £5.18 | (<1) | £8.03 | (<1) |

| Laboratory tests | £2.85 | (<1) | £2.85 | (<1) | £2.85 | (<1) |

| Tissue viability nurse visits | £0.25 | (<1) | £0.24 | (<1) | £0.27 | (<1) |

| Total | £7344.86 | (100) | £7162.81 | (100) | £7800.00 | (100) |

GP, general practitioner.

Figure 4.

Monthly cost of healthcare resource use associated with managing surgical wounds stratified by planned/emergency procedures and healing in clinical practice. NHS, National Health Service.

Table 7.

Cost of healthcare resource use associated with managing unhealed surgical wounds stratified by planned/emergency procedures and healing in clinical practice (percentage of total cost is in parenthesis)

| Resource | Mean cost of resource use per patient over 12 months from initial presentation in the community | |||||||

| Planned/healed procedures (%) | Planned/unhealed procedures (%) | Emergency/healed procedures (%) | Emergency/unhealed procedures (%) | |||||

| District nurse visits | £3457.82 | (58) | £8328.58 | (59) | £3104.09 | (52) | £7651.79 | (59) |

| Hospital admissions | £921.22 | (15) | £1284.56 | (9) | £1314.78 | (22) | £1536.34 | (12) |

| Dressings | £627.04 | (10) | £1661.62 | (12) | £558.83 | (9) | £1256.28 | (10) |

| Hospital outpatient visits | £293.21 | (5) | £526.69 | (4) | £331.36 | (6) | £611.42 | (5) |

| Practice nurse visits | £191.80 | (3) | £693.48 | (5) | £164.96 | (3) | £415.48 | (3) |

| GP visits | £182.28 | (3) | £500.49 | (4) | £161.89 | (3) | £307.56 | (2) |

| Bandages | £117.25 | (2) | £721.50 | (5) | £86.36 | (1) | £693.92 | (5) |

| Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories | £106.13 | (2) | £192.77 | (1) | £91.42 | (2) | £195.32 | (2) |

| Wound care appliances | £57.95 | (1) | £181.74 | (1) | £77.48 | (1) | £179.46 | (1) |

| Anti-infectives | £37.73 | (1) | £78.83 | (1) | £33.78 | (1) | £69.90 | (1) |

| Topical treatments | £6.21 | (<1) | £49.89 | (<1) | £39.62 | (1) | £0.00 | (<1) |

| Negative pressure wound therapy | £5.92 | (<1) | £0.69 | (<1) | £1.89 | (<1) | £25.30 | (<1) |

| Laboratory tests | £1.89 | (<1) | £8.70 | (<1) | £1.78 | (<1) | £5.86 | (<1) |

| Tissue viability nurse visits | £0.28 | (<1) | £0.00 | (<1) | £0.37 | (<1) | £0.00 | (<1) |

| Total | £6006.73 | (100) | £14 229.54 | (100) | £5968.61 | (100) | £12 948.63 | (100) |

GP, general practitioner.

Figure 5.

Cost of healthcare resource use associated with managing unhealed surgical wounds in clinical practice stratified by anatomical site of surgery. GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

District nurse visits were the primary cost driver and accounted for ≥52% of the cost of patient management. Hospital readmissions accounted for up to a further 22% of the cost and hospital outpatient visits a further 4%–6%. Dressings and bandages accounted for up to 17% of the cost of patient management. Eighteen per cent of the total NHS cost of managing a wound arising from a planned procedure and up to 23% for a wound arising from an emergency procedure was incurred in secondary care, the majority of which related to hospital readmission. The remainder was incurred in the community.

The mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months decreased inversely as a patient’s BMI increased (table 8). Additionally, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months was 43% more among patients with diabetes than among those without the disease (table 8).

Table 8.

Cost of healthcare resource use associated with managing unhealed surgical wounds stratified by BMI and diabetes

| Patients (%) | Healed (%) | Emergencies (%) | NHS cost per patient | |

| BMI<20 kg/m2 | 5 | 94 | 31 | £9269 |

| BMI 20–29 kg/m2 | 45 | 89 | 27 | £6938 |

| BMI 30–35 kg/m2 | 20 | 84 | 35 | £7096 |

| BMI>35 kg/m2 | 20 | 84 | 28 | £7812 |

| Diabetes | 29 | 80 | 33 | £9349 |

| No diabetes | 71 | 88 | 27 | £6526 |

BMI, body mass index; NHS, National Health Service.

Infection

The terms ‘surgical site infection’ and ‘SSI’ were not found in any of the patients’ case records. The most frequently used terms in the records were ‘postoperative wound infection’, ‘skin and subcutaneous tissue infection’, ‘local infection of skin/subcutaneous tissue’ and ‘cellulitis of wound’.

Thirteen per cent of the patients’ records documented their wound as being clinically infected at the onset of their management in the community. Another 55% of patients were prescribed a systemic anti-infective and/or antimicrobial dressing at this time, suggesting that as many as 68% of all the wounds in our study population may have been considered to be at risk of infection or infected at the time of initial presentation in the community (table 9). Additionally, 31% of patients with a putative infection had diabetes compared with 18% of patients who did not have an infection; p<0.005.

Table 9.

Incidence of putative infection with associated healing and costs over the 12 months’ follow-up period

| Patients (%) | Patients who healed (%) | Mean time to healing per patient (months) | Mean cost of wound care per patient | |

| No infection | 16 | 92 | 1.86 | £2001 |

| Received only an antimicrobial dressing | 18 | 83 | 5.79 | £6966 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective with or without an antimicrobial dressing | 66 | 85 | 6.46 | £8742 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective with an antimicrobial dressing | 41 | 82 | 8.11 | £11 169 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective without an antimicrobial dressing | 25 | 90 | 3.62 | £4961 |

Over the 12 months’ follow-up period, 18% of patients received only an antimicrobial dressing, indicative of concern about the local bioburden or a possible localised wound infection, and 66% were prescribed a systemic anti-infective. The duration of continuous prescribing of an antimicrobial dressing in the patients’ records was a mean of 4.2 months per patient. However, 28% of patients received continuous prescribing of topical antimicrobials for >6 months, according to documentation in their case record.

Of the 16% of patients who were never recorded as having an infection, 92% of the wounds healed within a mean of 1.9 months. The healing rate was lower among patients with a putative infection, and the mean time to healing was longer (table 9). Furthermore, the cost of wound management of an uninfected wound was at least 60% less than that of a putatively infected wound (table 9). The percentage of putative infections and associated costs was relatively unaffected by whether the wound had arisen from a planned or emergency procedure (table 10). Hence, the mean NHS cost of managing an unhealed surgical wound without any evidence of infection was estimated to be ~£2000 per wound, and the mean conflated cost of managing an unhealed surgical wound with a putative infection ranged from £5000 to £11 200 per wound.

Table 10.

Incidence of putative infection with associated healing and costs stratified by planned/emergency procedures over the 12 months’ follow-up period

| Cohort (%) | Cohort that healed (%) | Mean time to healing per patient (months) | Mean cost of wound care per patient | |

| Planned procedures | ||||

| No infection | 17 | 90 | 1.81 | £2143 |

| Received only an antimicrobial dressing | 17 | 86 | 5.99 | £6966 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective with or without an antimicrobial dressing | 66 | 87 | 6.66 | £8507 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective with an antimicrobial dressing | 43 | 84 | 8.19 | £10 606 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective without an antimicrobial dressing | 23 | 93 | 3.79 | £4581 |

| Emergency procedures | ||||

| No infection | 16 | 97 | 1.97 | £1649 |

| Received only an antimicrobial dressing | 21 | 79 | 5.29 | £7165 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective with or without an antimicrobial dressing | 63 | 79 | 5.98 | £9574 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective with an antimicrobial dressing | 38 | 76 | 7.93 | £12 018 |

| Prescribed an anti-infective without an antimicrobial dressing | 25 | 83 | 3.20 | £5633 |

Additionally, 23% of patients subsequently developed a putative wound infection a mean 4.3 months after initial presentation, for which an anti-infective was prescribed. The cost of wound management among these patients was a mean of £12 890 per patient.

Binary logistic regression showed that within the limitations of the data documented in the records of this cohort of patients, the anatomical site of surgery, prior presence of immunological symptoms and diabetes were all potential independent risk factors for patients developing an infection:

Chest and breast surgery: OR 3.231 (95% CI 1.127 to 9.263); p=0.029.

Immunological symptoms: OR 2.678 (95% CI 1.197 to 5.992); p=0.016.

Lower limb (vascular) surgery: OR 2.485 (95% CI 1.130 to 5.466); p=0.024.

Abdomen surgery: OR 1.814 (95% CI 1.076 to 3.058); p=0.025.

Diabetes: OR 1.734 (95% CI 1.025 to 2.933); p=0.04.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis showed that:

If the probability of healing was reduced by 25%, from 83% to 62%, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would increase by 22% to an estimated £8929 per wound. Conversely, if the probability of healing was increased by 20%, from 83% to 99%, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would decrease by 17% to an estimated £6077 per wound.

If the number of district nurse visits changed by 25% below or above the base case value, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would vary by 14% from the mean value (range £6298–£8392 per wound).

If the number of practice nurse visits changed by 25% below or above the base case value, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would vary by 1% from the mean value (range £7282–£7408 per wound).

If the number of hospital admissions changed by 25% below or above the base case value, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would vary by 4% from the mean value (range £7073–£7617 per wound).

If the number of hospital outpatient visits changed by 25% below or above the base case value, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would vary by 1% from the mean value (range £7258–£7432 per wound).

If the unit cost of wound care products was decreased or increased by 25%, the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months would vary by 4% from the mean value (range £7074–£7616 per wound).

Changes to the use of other healthcare resources had minimal impact on the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months, following initial presentation in the community.

Discussion

This study’s population comprised those patients who were discharged from hospital into the community with a wound that remained unhealed for longer than 4 weeks after their surgery, and may well be different from the cohort of patients whose wound heals within 4 weeks of their surgical procedure or those who remain in hospital until their surgical wound heals. Nevertheless, this analysis provides the first evidence of how unhealed surgical wounds are managed in clinical practice in the UK, following initial presentation in the community.

This cohort consisted of patients with SWD or an open wound left to heal by secondary intention. SSI is one of the risk factors for SWD, but the occurrence of SWD can increase the risk of developing an SSI.18 Although the secondary care and economic implications of SSI are well recognised,19 20 those of SWD remain largely unquantified,21 as is the community cost of treating both.22 One study comments that a rigorous and consistent classification system is needed if patients with SWD are to be effectively diagnosed and managed.21 Our study found considerable variation in documentation standards and terminology pertaining to both the nature of the wound and infection. Consequently, any reporting system on SWD and SSI in the community would be under-reported and inaccurate. In an attempt to address this variance, a post-discharge SSI assessment has been developed and is currently undergoing further testing.23

The lack of secondary care involvement in many of the cases identified in this study would suggest that surgical teams may be unaware of the extent of the problem, and that both SWD and SSI may therefore be under-reported. A point prevalence study of wounds in north-east England identified that the largest proportion of wounds was surgical wounds, and that community nurses were involved in the care of over 70% of patients with wounds.24 Another study found that one-third of surgical complications occurred after discharge, that two-thirds were managed in the community and that one-third resulted in readmission to hospital.25 The authors emphasised that research and audit based solely on inpatient data significantly underestimates surgical wound morbidity rates.25 In comparison, 19% of this study’s patients were readmitted into hospital as a direct result of their unhealed surgical wound.

Our analysis suggests that unhealed surgical wounds occur in patients with significant comorbidities, the management of which is associated with significant resource use. Moreover, two-thirds of all the unhealed surgical wounds in this cohort were considered to be at risk of infection or infected at the time of presentation. This estimate was based on documentation of infection in the patients’ records and the use of antimicrobial dressings and anti-infective prescriptions. The authors recognise the potential weakness of this estimate as systemic anti-infectives can be prescribed in general practice on the basis of wound swabs alone. Furthermore, antimicrobial dressings are prescribed prophylactically in clinical practice for wounds that are both infected and uninfected. The relative effectiveness of any antiseptic, antibiotic or antibacterial agent delivered either systemically or topically on surgical wounds healing by secondary intention is unclear.26 NICE recommends that patients with an SSI are offered treatment with an antibiotic that covers the likely causative organisms, and is selected based on local resistance patterns and the results of microbiological tests.9 Moreover, prophylactic use of antibiotics carries a risk of adverse effects and increased prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Therefore, NICE recommends that prophylactic use of antibiotics should be limited to cover the organisms most likely to cause infection and be influenced by the strength of the association between the antibiotic used and these adverse effects.9

Resource use associated with managing a putatively infected wound was found to be greater than that of an uninfected wound as the healing rate was lower and time to healing was longer. So too was resource use associated with managing the wounds that remained unhealed compared with those that went on to heal. Consequently, the cost of managing an unhealed wound was at least double that of managing a wound that healed (mean of £5997 vs £13 682 per wound), and the cost of managing an uninfected wound was at least 60% less than that of a putatively infected wound. The mean cost of managing a putatively infected wound with an anti-infective and an antimicrobial dressing (£11 200) was not too dissimilar to Tanner’s cost estimate of managing a postsurgical wound infection in the community (£10 523).27 Moreover, the analysis found the mean NHS cost of wound care over 12 months from initial presentation in the community to be an estimated £7300 per wound, ranging from a mean of £7200 to £7800 for a wound that arose from a planned or emergency procedure, respectively. It is important to note that these estimates are the amounts by which the costs of the original episodes of surgery are increased as a result of the surgical wound not having healed. Others have also reported that SWD increases healthcare expenditure, due in part to the need for community nursing and associated support and increased use of wound care products.19 28–32

These findings from this cohort of patients with unhealed surgical wounds are consistent with our Burden of Wounds study.11 12 33 The time to healing a wound is clearly an important factor in driving costs. Accordingly, the cost of surgical wound management can be affected by a combination of resources required for dressing changes, complexity of some treatment regimens and infection.12 Furthermore, the Burden of Wounds study11 12 33 provided insight into areas where care improvements could potentially result in improved clinical outcomes while generating significant cost savings. Nevertheless, cost-effective management and healing of unhealed surgical wounds in the community is likely to remain a challenging problem. One of the reasons may be due to the inadequate involvement of specialist clinicians in the management of the wounds in this study’s cohort. Only three patients were recorded as having seen a tissue viability nurse and around a half of all patients who still had a wound at 3 months were recorded as having had a follow-up outpatient visit with their surgeon. However, it is possible that more patients were receiving multidisciplinary care than those for whom that was recorded in the THIN database. However, there was minimal evidence of this within the records, and there was no evidence of a coordinated shared treatment plan.

This study highlights the apparent lack of treatment planning, reassessment and re-evaluation of care for most patients with an unhealed surgical wound in the community. The patients’ combination of dressings and bandages remained unchanged for the length of time the wound remained unhealed, and there was minimal correlation between wound duration and senior involvement in direct patient care. Given the nature of these wounds, there was a surprising underutilisation of topical negative pressure therapy in this cohort of patients. This may have resulted from either a lack of product availability, item cost considerations, skill mix and/or a failure to follow escalation pathways involving senior staff. Another community-based study in Australia reported similar findings,21 and interestingly, the distribution of dressing use in our study was concordant with that used to treat SWD in the Australian study.21 Clearly, improving management practices should lead to a better outcome for patients and would be cost-effective for the NHS.

The authors suggest that an improvement in five key areas of clinical and service management would enhance healing and other patient outcomes while reducing overall management costs. These are:

Working to common definitions and reporting standards across primary and secondary care.

Integrating care across providers.

Escalating care appropriately with greater senior involvement.

Rational use of products with access to advanced wound treatments when necessary.

Recognising high-risk patients and responding with nutritional support and comorbidity management as appropriate.

In turn, with improved healing, these actions should reduce workload and associated healthcare resource use and lead to reductions in the overall cost of wound care. All healthcare systems recognise the importance of managing unhealed surgical wounds and the relative risk of developing an SSI. Clearly, training non-specialist nurses in the appropriate management of unhealed surgical wounds is a prerequisite to overcoming some of the problems encountered in clinical practice and to achieving better health outcomes than those currently being observed.

Study limitations

The advantages and disadvantages of using patients’ records in the THIN database for health economic studies in wound care have been previously discussed.11 In summary, the advantage of using the database is that the patient pathways and associated resource use are based on real-world evidence derived from clinical practice. However, the analyses were based on clinicians’ entries into their patients’ records and inevitably subject to a certain amount of imprecision and lack of detail. Moreover, the computerised information in the database is collected by GPs and nursing teams for clinical care purposes and not for health economics research. Prescriptions issued by GPs and practice nurses are recorded in the database, but it does not specify whether the prescriptions were dispensed or detail patient compliance with the product. Additionally, the patients’ records do not consistently document plasma glucose levels and amounts of alcohol intake, both of which could potentially impact on wound healing. Despite these limitations, it is the authors’ opinion that the real-world evidence contained in the THIN database has provided a useful perspective on the management of unhealed surgical wounds in the community in the UK and the associated costs.

The analysis was truncated at 12 months and does not consider the potential impact of those wounds that remained unhealed beyond the study period. Also excluded is the potential impact of managing hospital inpatients with a surgical wound and those being cared for in nursing/residential homes. The analysis only considered NHS resource use and associated costs for the ‘average patient’ and was not stratified according to gender, comorbidities, disease-related factors and level of clinicians’ skills. Costs incurred by non-NHS organisations (such as the provision of social care), patients’ costs and indirect societal costs as a result of patients being absent from work were also excluded from the analysis.

Further research is required to quantify both the incidence and prevalence of unhealed surgical wounds, SWD and SSI in the community and to elucidate more fully the risk factors for their development.

Conclusion

The real-world evidence in this study provides important insights into a number of aspects of surgical wound management in clinical practice in the community in the UK that have been difficult to ascertain from other published studies. Surgeons are unlikely to be fully aware of the problems surrounding unhealed surgical wounds once patients are discharged into the community, due to inconsistent recording in patients’ records coupled with the finding that only around a half of all patients who still had a wound at 3 months saw their surgeon for a follow-up appointment. Additionally, it provides the best estimate available of NHS resource use and costs with which to inform policy and budgetary decisions pertaining to managing these wounds. Clinical and economic benefits to both patients and the NHS could accrue from strategies that focus on improving documentation in patients’ records, wound healing rates and reducing infection. Clinicians managing unhealed surgical wounds may wish to consider the findings from this study when making treatment decisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kathryn Vowden, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Bradford, UK, and University of Bradford, Bradford, UK, for her review and invaluable input into this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: JFG designed the study, managed the analyses, performed some analyses, checked all the other analyses and wrote the manuscript. GWF conducted much of the analyses. PV scrutinised the analyses, suggested further analyses and helped interpret some of the findings. All the authors were involved in revising the manuscript and gave final approval. JFG is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This analysis was originally commissioned and part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Wound Prevention and Treatment Healthcare Technology Co-operative (NIHR WoundTec HTC), Bradford Institute for Health Research, Bradford, West Yorkshire, UK, and part funded by Smith & Nephew Medical, Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire, UK.

Disclaimer: The study’s sponsors had no influence on (1) the study design; (2) the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; (3) the writing of the manuscript; or (4) the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NIHR and Smith & Nephew.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval to use anonymised patients’ records from the THIN database for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee that appraises studies using the THIN database (reference number 13-061).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The THIN data set cannot be shared as this restriction was a condition of the ethics approval obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13-061). This statement is correct

References

- 1. NHS Confederation. NHS statistics, facts and figures. 2017. http://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/key-statistics-on-the-nhs.

- 2. NHS Digital. Hospital episode statistics 2015/16. England, 2017. https://digital.nhs.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moore P, Foster L. Acute surgical wound care 1: an overview of treatment. Br J Nurs 1998;7:1101–6. 10.12968/bjon.1998.7.18.5588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Surgical site infection: Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vowden KR, Vowden P. The prevalence, management and outcome for acute wounds identified in a wound care survey within one English health care district. J Tissue Viability 2009;18:7–12. 10.1016/j.jtv.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sussman C, Bates-Jensen B. Wound care: a collaborative practice manual for health professionals. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. . Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999;20:250–78. 10.1086/501620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scalise A, Calamita R, Tartaglione C, et al. . Improving wound healing and preventing surgical site complications of closed surgical incisions: A possible role of incisional negative pressure wound therapy. A systematic review of the literature. Int Wound J 2016;13:1260–81. 10.1111/iwj.12492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013. Surgical site infection: prevention and treatment of surgical site infection. Clinical guideline [CG74] https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG74

- 10. Tanner J, Khan D. Surgical site infection, preoperative body washing and hair removal. J Perioper Pract 2008;18:7–43. 10.1177/175045890801800602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guest JF, Ayoub N, McIlwraith T, et al. . Health economic burden that wounds impose on the National Health Service in the UK. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009283 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guest JF, Ayoub N, McIlwraith T, et al. . Health economic burden that different wound types impose on the UK’s National Health Service. Int Wound J 2017;14:322–30. 10.1111/iwj.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. House of Lords Hansard, 2017. House of Lords debate on developing a strategy for improving the standards of wound care in the NHS https://hansard.parliament.uk/lords/2017-11-22/debates/6C57E65A-A04D-449B-82E9-C836F088A696/NHSWoundCare.

- 14. Blak BT, Thompson M, Dattani H, et al. . Generalisability of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database: demographics, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates. Inform Prim Care 2011;19:251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2016. Canterbury: University of Kent, Personal Social Services Research Unit, 2016. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/unit-costs-2016/ (accessed 12 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Department of Health. NHS reference costs 2015/16. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-2015-to-2016 (Accessed 12 Dec 2017).

- 17. Drug Tariff. Drug Tariff. 2016. https://www.drugtariff.co.uk accessed 12 Dec 2017.

- 18. Crawford M. Surgical complications and their treatments : Dockery G, Crawford M, Lower Extremity Soft Tissue & Cutaneous Plastic Surgery. 2nd Edition: Saunders Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leaper DJ, van Goor H, Reilly J, et al. . Surgical site infection - a European perspective of incidence and economic burden. Int Wound J 2004;1:247–73. 10.1111/j.1742-4801.2004.00067.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sullivan E, Gupta A, Cook CH. Cost and consequences of surgical site infections: A call to arms. Surg Infect 2017;18:451–4. 10.1089/sur.2017.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sandy-Hodgetts K, Leslie GD, Lewin G, et al. . Surgical wound dehiscence in an Australian community nursing service: time and cost to healing. J Wound Care 2016;25:377–83. 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.7.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Orsted HL, Keast DK, Kuhnke J, et al. . Best practice recommendations for the prevention and management of open surgical wounds. Wound Care Canada 2010;8:6–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Macefield RC, Reeves BC, Milne TK, et al. . Development of a single, practical measure of surgical site infection (SSI) for patient report or observer completion. J Infect Prev 2017;18:170–9. 10.1177/1757177416689724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Srinivasaiah N, Dugdall H, Barrett S, et al. . A point prevalence survey of wounds in north-east England. J Wound Care 2007;16 413–9. 10.12968/jowc.2007.16.10.27910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Woodfield JC, Jamil W, Sagar PM. Incidence and significance of postoperative complications occurring between discharge and 30 days: a prospective cohort study. J Surg Res 2016;206:77–82. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Norman G, Dumville JC, Mohapatra DP, et al. . Antibiotics and antiseptics for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD011712 10.1002/14651858.CD011712.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tanner J, Khan D, Aplin C, et al. . Post-discharge surveillance to identify colorectal surgical site infection rates and related costs. J Hosp Infect 2009;72:243–50. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guest JF, Ruiz FJ, Tang R, et al. . Cost implications of post-surgical morbidity following blood transfusion in cancer patients undergoing elective colorectal resection: an evaluation in the US hospital setting. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:447–55. 10.1185/030079905X30734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Urban JA. Cost analysis of surgical site infections. Surg Infect 2006;7 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):s19–s22. 10.1089/sur.2006.7.s1-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reilly J, Twaddle S, McIntosh J, et al. . An economic analysis of surgical wound infection. J Hosp Infect 2001;49:245–9. 10.1053/jhin.2001.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Lissovoy G, Fraeman K, Hutchins V, et al. . Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J Infect Control 2009;37:387–97. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Graf K, Ott E, Vonberg RP, et al. . Economic aspects of deep sternal wound infections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:893–6. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guest JF, Vowden K, Vowden P. The health economic burden that acute and chronic wounds impose on an average clinical commissioning group/health board in the UK. J Wound Care 2017;26 292–303. 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.6.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.