Abstract

Objective

To investigate the efficacy and safety of the pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy in treating osteoarthritis (OA).

Design

Meta-analysis.

Data sources

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library and Web of Science were searched through 13 October 2017.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Randomised controlled trials compared the efficacy of PEMF therapy with sham control in patients with OA.

Data extraction and synthesis

Pain, function, adverse effects and characteristics of participants were extracted. RevMan V.5.2 was used to perform statistical analyses.

Results

Twelve trials were included, among which ten trials involved knee OA, two involved cervical OA and one involved hand OA. The PEMF group showed more significant pain alleviation than the sham group in knee OA (standardised mean differences (SMD)=−0.54, 95% CI −1.04 to –0.04, p=0.03) and hand OA (SMD=−2.85, 95% CI −3.65 to –2.04, p<0.00001), but not in cervical OA. Similarly, comparing with the sham–control treatment, significant function improvement was observed in the PEMF group in both knee and hand OA patients (SMD=−0.34, 95% CI −0.53 to –0.14, p=0.0006, and SMD=−1.49, 95% CI −2.12 to –0.86, p<0.00001, respectively), but not in patients with cervical OA. Sensitivity analyses suggested that the exposure duration <=30 min per session exhibited better effects compared with the exposure duration >30 min per session. Three trials reported adverse events, and the combined results showed that there was no significant difference between PEMF and the sham group.

Conclusions

PEMF could alleviate pain and improve physical function for patients with knee and hand OA, but not for patients with cervical OA. Meanwhile, a short PEMF treatment duration (within 30 min) may achieve more favourable efficacy. However, given the limited number of study available in hand and cervical OA, the implication of this conclusion should be cautious for hand and cervical OA.

Keywords: eoarthritis, pulsed electromagnetic field, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provided a comprehensive assessment on the efficacy and safety of the pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy in patients with knee, hand and cervical osteoarthritis (OA).

All included studies in this meta-analysis were randomised controlled trials.

There was a high level of heterogeneity among various studies, because different treatment protocols of PEMF were used in the included studies.

There were sparse eligible trials available for the efficacy analysis of hand OA and cervical OA, and the reliability of the conclusions on these two joints were limited.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a widespread degenerative disease, which can lead to pain, physical dysfunction and even disability. The joints most commonly affected by OA include knees, hips, hands, neck and feet.1 2 A variety of medications and physical therapies have been used in the treatment of OA. However, some widely applied drugs (eg, chondroitin, glucosamine, intra-articular hyaluronic acid, etc) or physical treatments (eg, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and ultrasound) are actually not advocated by the recent Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines.3 To date, few effective treatments for knee OA are available.

Since the early 1980s, researchers have found that pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy could be applied to accelerate wound healing, repair fracture, reduce haematoma and treat soft tissue injury and inflammation.4 In addition, some studies have demonstrated that PEMF could activate the signal transduction pathway5–7 and induce the human articular chondrocyte proliferation.8 Being a simple, non-invasive and safe physical therapy, PEMF was considered to be an alternative treatment regimen for OA. During the past two decades, more than 10 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted to explore the efficacy of PEMF in the treatment of OA, but no consensus was reached yet.9–22 Several previous meta-analyses have evaluated the combined effects of PEMF and pulsed electrical stimulation (PES) on OA.23 24 However, the mechanisms of PEMF and PES were totally different. For example, PES is delivered through capacitive coupling using transcutaneous electrodes and coupling agents25 relying on the direct application of an electrical field, whereas PEMF creates induced current through magnetic impulse.24 To the best of our knowledge, few meta-analyses have evaluated the efficacy and safety of single PEMF for OA.

To fill in this knowledge gap, the purpose of the present study was to provide a comprehensive assessment on the efficacy and safety of single PEMF in patients with OA at different joints. It was hypothesised that PEMF could relieve pain and improve the physical function of patients with OA without producing side effects.

Methods

Search strategies and studies selection

The study records were identified in four electronic databases of PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library and Web of Science through using the combination of a series of keywords and text terms describing OA and PEMF (see online supplementary appendix 1). The latest literature search was conducted on 13 October 2017. Studies were included if: (1) subjects had symptomatic or radiographic OA, (2) the intervention contained PEMF versus sham–control, (3) the study was designed as an RCT, (4) the primary outcome included pain and/or function. Studies were excluded if: (1) experimental studies (eg, in vitro studies, animal studies or cadaveric studies), (2) studies for postoperation rehabilitation, (3) subjects treated by short wave or PES or any other physical therapies, (4) studies cannot get full text, (5) studies no data available, (6) unbalanced additional non-pharmacological treatments (eg, exercise or hot pack) between groups.

bmjopen-2018-022879supp001.pdf (283KB, pdf)

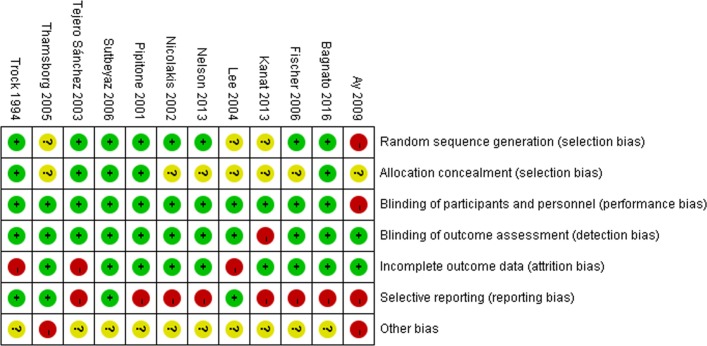

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of each included trial was evaluated by two independent authors based on the Cochrane handbook,26 27 which consists of seven domains: generation of randomisation sequences, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and implementers, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other potential biases. Furthermore, any of divergence was to be discussed and a third consultant was needed if necessary.28 29 Trials involving three or more high risks of bias were considered as poor methodological quality.30

Data extraction and outcome measure

All the data were extracted by two independent authors. The extracted information included the characteristics of participants (age, gender, body mass index and duration of OA), balance intervention between groups, number of participants in each trial, treatment protocol of PEMF and the type of outcome measures, baseline data, post-treatment data and mean changes and SD or the information from which SD could be derived, such as SE or CI. The primary goal of this study was to assess the efficacy of pain alleviation and function improvement by applying the PEMF therapy for patients with OA. Adverse events (AEs) were considered as the safety outcome. The efficacy of pain alleviation was measured by change of pain intensity from baseline.31 Data at the last follow-up time point after treatment were extracted to calculate the change degree from baseline to the last follow-up. According to the recommended hierarchy of continuous pain-related outcomes used in the meta-analyses,32 33 the outcome data expressed in higher ranking scale were extracted if multiple pain scale measured simultaneously. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) function was the preferred measure for function outcome. If a study did not measure or report the WOMAC function, WOMAC total, Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) social function score or total score and physician global assessment scores were used in the analysis instead.34 The number of participants who reported AEs were also extracted in order to evaluate the safety of interventions.

Statistical analysis

The Review Manager V.5.2 was used to perform all the statistical analyses. As the outcome of pain and function reported by continuous data and various scales were used for outcome assessment, the standardised mean differences (SMDs) were calculated to compare the effect of pain alleviation and function improvement between different intervention groups. For the safety outcome, the relative risk (RR) was calculated to compare the safety between the two groups. Trials that reported zero AE in both the PEMF and the sham groups were not included in the AEs analysis.26 Ninety-five per cent CI was calculated for pooled estimates for each outcome. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05. A random model was applied to pool the data. Q and I2 statistics were calculated to assess the heterogeneity among the included studies, with a p value >0.05 of the Q statistics and I2 value <50% indicating statistical homogeneity. It is hypothesised that different exposure duration of PEMF and disease location will influence treatment effect. Therefore, subgroup analyses were performed according to the exposure duration of PEMF therapy (no more than 30 min per session or more than 30 min per session)5–7 and location of OA. Funnel plots were inspected to assess publication bias.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of public were involved in the present study. No patients were asked to advise on the interpretation or writing up of results. The results of the present research will be communicated to the relevant patient community.

Results

Study screening and characteristics of included studies

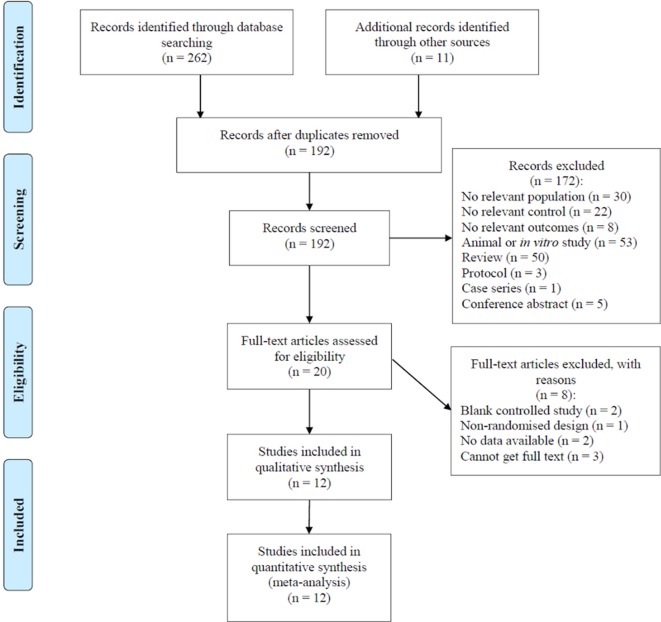

Figure 1 showed the flow diagram for study screening. One hundred and ninety-two records were identified initially and 12 studies9–20 met the eligibility criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. The characteristics of included studies are summarised in table 1. The risk of bias assessment (figure 2) showed that one study9 was regarded as low quality.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of studies screening process based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Studies | Balance | N | Location of OA | Age, years (mean±SD) |

Female % |

Mean BMI, kg/m2

(mean±SD) |

Duration of OA, years (mean±SD) |

Exposure of intervention | Time point for outcome measure | ||

| Daily time | Exposure duration | ||||||||||

| Ay9 | PEMF | Hot pack, TENS | 55 | Knee | 58.9±8.8 | 70.0 | NA | 3.6±4.6 | 30 min | 3 weeks (15 sessions) |

After treatment |

| Placebo | 57.7±6.5 | 76.0 | NA | 3.5±4.1 | |||||||

| Bagnato10 | PEMF | None | 60 | Knee | 67.7±10.9 | 70.0 | 27.4±4.3 | 12.1±8.2 | A minimum of 12 hours | 1 month (30 sessions) |

1 month |

| Placebo | 68.6±11.9 | 73.3 | 27.7±4.6 | 12.4±9.1 | |||||||

| Fischer11 | PEMF | None | 71 | Knee | 52.1±1.9 | 71.4 | 29.2±1.0 | 6.8±0.7 | 16 min | 6 weeks (42 sessions) |

Therapy-end, 4 weeks after therapy-end |

| Placebo | 62.1±1.5 | 72.2 | 29.4±0.7 | 6.2±0.6 | |||||||

| Lee13 | PEMF | None | 51 | Knee | 63.5±8.9 | 8.0 | 26.1±3.1 | 12.7±7.5 | 30 min | 6 weeks (18 sessions) | 3, 6 weeks during treatment, 4 weeks after finishing |

| Placebo | 66.2±8.8 | 11.5 | 27.1±3.7 | 12.8±7.6 | |||||||

| Nelson14 | PEMF | Current standard of care | 34 | Knee | 55.5±2.5 | 73.7 | 33.5±1.9 | NA | 15 min | 6 weeks (84 sessions) |

14, 29, 42 days |

| Placebo | 58.4±2.5 | 66.7 | 34.7±1.7 | NA | |||||||

| Nicolakis15 | PEMF | None | 36 | Knee | 69.0±5.0 | 73.3 | NA | NA | 30 min | 6 weeks (84 sessions) |

After treatment |

| Placebo | 67.0±7.0 | 47.1 | NA | NA | |||||||

| Pipitone16 | PEMF | None | 75 | Knee | 62.0 (40–84) * | 35.3 | NA | 4.0 (1.0–18.0) * | 10 min and three times a day | 6 weeks | 2, 4, 6 weeks after study entry |

| Placebo | 64.0 (48–84) * | 20.0 | NA | 8.0 (0.5–31.0) * | |||||||

| Tejero Sánchez18 | PEMF | None | 83 | Knee | 67.4±8.7 | 87.9 | NA | NA | 30 min | 20 sessions | The end of therapy, 1 month after therapy |

| Placebo | 68.0±8.3 | 88.2 | NA | NA | |||||||

| Thamsborg19 | PEMF | None | 83 | Knee | 60.4±8.7 | 46.5 | 27.0±4.0 | 7.5±5.2 | 2 hours | 6 weeks (30 sessions) |

2 weeks, end of treatment, 6 weeks after end of treatment |

| Placebo | 59.6±8.6 | 61.0 | 27.5±5.7 | 7.9±7.7 | |||||||

| Trock20 † | PEMF | Do not change basic therapeutic regimen | 86 | Knee | 69.2±11.5 | 69.0 | NA | 9.1±8.9 | 30 min | 4–5 weeks (18 sessions) |

Midway of therapy, the last treatment, and 1 month later |

| Placebo | 65.8±11.7 | 70.5 | NA | 7.4±7.2 | |||||||

| Sutbeyaz17 | PEMF | None | 34 | Cervical | 43.2±10.3 | 64.7 | NA | NA | 30 min | 3 weeks (42 sessions) |

After treatment |

| Placebo | 42.1±10.1 | 66.7 | NA | NA | |||||||

| Trock20 † | PEMF | Do not change basic therapeutic regimen | 81 | Cervical | 61.2±13.4 | 28.6 | NA | 7.4±6.7 | 30 min | 4–5 weeks (18 sessions) |

Midway of therapy, the last treatment, and 1 month later |

| Placebo | 67.4±8.0 | 30.8 | NA | 8.1±8.0 | |||||||

| Kanat12 | PEMF | Active range of motion and resistive exerciss | 50 | Hand | 64.0±2.60 | NA | NA | 5.01±2.3 | 20 min | 10 days | After treatment |

| Placebo | 62.0±2.40 | NA | NA | 4.31±4.7 | |||||||

*Age and duration of OA in this trial were expressed by median (range).

†This trial provided data of patients with knee OA and cervical OA, respectively.

BMI, body mass index; N, number of participates; NA, not available; OA, osteoarthritis; PEMF, pulsed electromagnetic field; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary of 12 included studies. The green background with ‘+’ means low risk of bias; the red background with ‘-’ means high risk of bias; the yellow background with ‘?’ means unknown risk of bias. Trials involving three or more high risks of bias were considered as poor methodological quality.

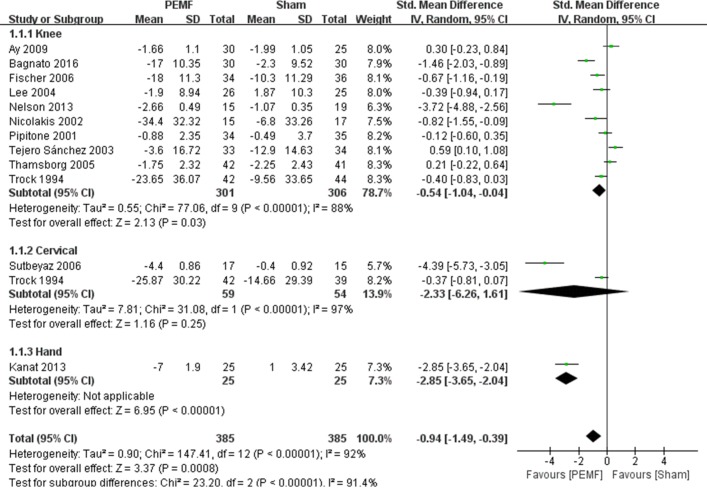

Pain relief

Twelve RCTs were included for meta-analysis of pain management.9–20 As shown in figure 3, PEMF group achieved a significant difference in pain improvement compared with the sham group (SMD=−0.94, 95% CI −1.49 to –0.39, p=0.0008), while significant heterogeneity was observed (I2=92%; p<0.00001). Subgroup analysis showed that significant differences were observed between the PEMF and sham group on pain improvement in patients with knee OA (SMD=−0.54, 95% CI −1.04 to –0.04, p=0.03) and hand OA (SMD=−2.85, 95% CI −3.65 to –2.04, p<0.00001), whereas no significant difference was achieved between groups in patients with cervical OA (SMD=−2.33, 95% CI −6.26 to 1.61, p=0.25). As for subgroup analysis of different exposure duration, significant difference was observed with exposure duration within 30 min (SMD=−1.01, 95% CI −1.64 to –0.39, p=0.001), and no significant difference was achieved between intervention groups with exposure duration of more than 30 min (SMD=−0.61, 95% CI −2.25 to 1.02, p=0.46) (see table 2). Besides, substantial asymmetry was not identified in the funnel plot.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) compared with sham–control on pain. Significant differences were observed between the PEMF and sham group on pain improvement in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) (p=0.03) and hand OA (p<0.00001), whereas no significant difference was achieved between groups in patients with cervical OA (p=0.25).

Table 2.

Results of subgroup analyses

| Reason for subgroup analyses | Pooled results of subgroups | Heterogeneity of subgroups | ||

| SMD/RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | P values | ||

| Pain | ||||

| Location | Knee OA | −0.54 (−1.04 to 0.04) | 88 | 0.03 |

| Cervical OA | −2.33 (−6.26 to 1.61) | 97 | 0.25 | |

| Hand OA | −2.85 (−3.65 to 2.04) | NA | <0.00001 | |

| Exposure duration | No more than 0.5 hour/session | −1.01 (−1.64 to 0.39) | 91 | 0.001 |

| More than 0.5 hour/session | −0.61 (−2.25 to 1.02) | 95 | 0.46 | |

| Function | ||||

| Location | Knee OA | −0.34 (−0.53, to 0.14) | 0 | 0.0006 |

| Cervical OA | −0.27 (−0.71 to 0.16) | NA | 0.22 | |

| Hand OA | −1.49 (−2.12 to 0.86) | NA | <0.00001 | |

| Exposure duration | No more than 0.5 hour/session | −0.50 (−0.81 to 0.18) | 59 | 0.002 |

| More than 0.5 hour/session | −0.33 (−0.82 to 0.17) | 54 | 0.20 | |

| Adverse event | ||||

| Exposure duration | No more than 0.5 hour/session | 0.42 (0.14 to 1.29) | 0 | 0.13 |

| More than 0.5 hour/session | 1.95 (0.81 to 4.71) | NA | 0.14 | |

NA, not available.; OA, osteoarthritis; RR, relative risk; SMD, standard mean difference.

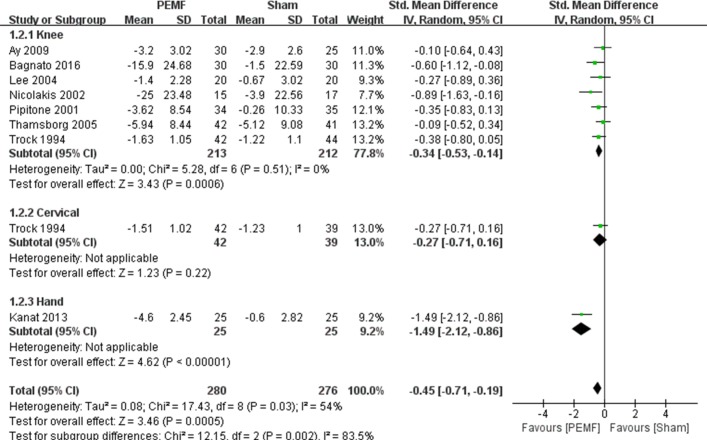

Function improvement

Eight RCTs were included for meta-analysis of physical function improvement.9 10 12 13 15 16 19 20 Figure 4 illustrated the beneficial effect of PEMF on physical function improvement (SMD=−0.45, 95% CI −0.71 to –0.19, p=0.0005), and substantial heterogeneity was observed (I2=54%; p=0.03). However, the subgroup analysis of different OA locations suggested significant differences both in knee OA and hand OA (SMD=−0.34, 95% CI −0.53 to –0.14, p=0.0006, and SMD=−1.49, 95% CI −2.12 to –0.86, p<0.00001, respectively, see table 2), whereas there was no significant difference between groups in patients with cervical OA (SMD=−0.27, 95% CI −0.71 to 0.16, p=0.22). In addition, there was a significant difference on effect of function improvement with exposure duration within 30 min (SMD=−0.50, 95% CI −0.81 to 0.18, p=0.002), and no significant difference was observed in more than 30 min group (SMD=−0.33, 95% CI −0.82 to 0.17, p=0.20). Funnel plot also did not identify substantial asymmetry.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) compared with sham–control on function. There were significant differences both in knee osteoarthritis (OA) (p=0.0006) and hand OA (p<0.00001), whereas there was no significant difference between groups in patients with cervical OA (p=0.22).

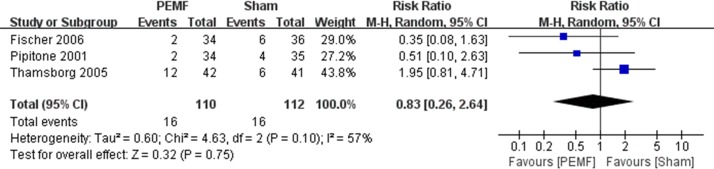

Adverse events

There were 10 RCTs that reported AEs.9–11 13 14 16–20 Seven of them claimed that no AEs were observed both in PEMF and sham group.9 10 13 14 17 18 20 Three trials reported the AEs of each treatment group, which mainly included increased knee pain, hip pain, spine pain, vomiting, warming sensation, increased blood pressure, numbness of feet, paraesthesia of foot and cardiomyopathy, and there were no AE-related dropouts in each trial.11 16 19 There was no significant difference between the PEMF and the sham group regarding AEs (RR=0.83, 95% CI 0.26 to 2.64, p=0.75) (figure 5). Substantial asymmetry was not identified in the funnel plot.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) compared with sham–control on adverse events. There was no significant difference between the PEMF and the sham group regarding adverse events (p=0.75).

Discussion

This study provided a comprehensive assessment of the scientific literature on the efficacy and safety of the PEMF therapy in patients with knee, hand and cervical OA. The results showed that, in comparison with the sham–control group, PEMF was more effective in both pain relief and function improvement for patients with knee OA and hand OA, but not for patients with cervical OA. In addition, PEMF did not lead to specific AEs compared with the sham–control group. Interestingly, a short duration of PEMF treatment for <=30 min per session seems to achieve more favourable results. This finding may have significant implications for the clinical application of PEMF in the OA field.

As a non-invasive, safe and simple therapy, the PEMF therapy is widely used to treat soft injury and bone fracture and relieve pain and inflammation, as well as many other types of diseases and pathologies.35 In the past two decades, researchers have turned their attention to the efficacy of treating OA. Some previous systematic reviews have combined PEMF and other physical therapies together to examine their efficacy in patients with OA, which might bias the results. McCarthy et al 36 demonstrated that PEMF and short wave together had limited effect in treating knee OA. In contrast, We et al 37 reported different results. Based on the follow-up data extracted from different time points for subgroup analysis, they concluded that the combination of PEMF and short wave was more effective in functional improvement, but not in pain relief, at 8 weeks after the first treatment.37 It should be noted that short wave therapy was considered to be another type of physical therapy which was different from PEMF.38 Similarly, another study conducted by Li et al 24 reported that PEMF and PES might provide moderate benefit for OA sufferers in terms of pain relief. However, considering that PES relies on the direct application of an electrical field and PEMF creates induced current through magnetic impulse, the combined analysis of these two physical therapies may also bias the results.

The results of the present study showed that PEMF had significant effects in pain alleviation and function improvement compared with the sham–control group in patients with knee and hand OA, but not in patients with cervical OA. The poor efficacy of the treatment for cervical OA may be due to the anatomical factors of cervical spine. The neurovascular structures contained in the cervical spinal canal may be compressed due to cervical OA, which will then induce a series of symptoms, such as the upper limb nerve root pain induced by nerve root compression, the chronic vertebral and basilar arterial insufficiency due to compression of vertebral arteries and the numbness of limbs and easiness to falling caused by spinal cord compression.39 40 Although some studies showed that PEMF could enhance articular cartilage regeneration,41 42 no evidence yet demonstrated that PEMF can reduce osteophytes formation, which may induce nerve root compression that can lead to deterioration of pain and function. In addition, the limited number of studies available is another reason that should not be ignored.

The present study further examined the association between the exposure duration of PEMF and efficacy for patients with OA. The results suggested that the exposure duration <=30 min per session could achieve better efficacy both in pain relief and function improvement. The reason could be explained by several previous laboratory studies. A recent study exploring the effects of different PEMF treatment durations (ranged from 5 to 60 min) over the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) chondrogenic differentiation reported that the expression of MSC chondrogenic markers showed the greatest increase in response to 5–20 min PEMF treatment.43 Similarly, another two studies which have shown that PEMF could activate cellular signaling transduction rapidly within 5–10 min, whereas the signaling might be largely dulled after 30 min.5–7

Nevertheless, limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, since different treatment protocols of PEMF were used in the included studies, there was a high level of heterogeneity among various studies. Second, there were sparse eligible trials available for the efficacy analysis of hand OA and cervical OA, and the accuracy of the conclusions on these two joints were limited. In addition, because the number of studies reporting the pulse frequency of application, pulse intensity, pulsed rate and other parameters of PEMF was very limited, subgroup analyses were restricted according to these parameters of PEMF. Finally, morphological change is a meaningful outcome for exploring the treatment efficacy of PEMF further19; however, the morphological changes were not reported in the present study due to the lack of relevant data. More trials are needed to evaluate the morphological changes after PEMF therapy.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that PEMF could alleviate pain and improve physical function for knee and hand OA patients, but not for cervical OA. Meanwhile, a short PEMF treatment duration (within 30 min) may achieve more favourable efficacy. However, given the limited number of studies available in hand and cervical OA, the implication of this conclusion should be cautious for hand and cervical OA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

ZW and XD contributed equally.

YW and DX contributed equally.

Contributors: ZW, DX, XD and YW were responsible for the conception and design of the study. ZW, XD, DX and YW contributed to the study retrieval. YC and YX contributed to quality assessment. HL, TY and JL contributed to the data collection. JW and CZ contributed to statistical analysis. ZW, XD, DX and YW drafted the manuscript. CZ and GL contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81472130, 81672225, 81601941, 81501923, 81772413, 81702207, 81702206), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central SouthUniversity (182130), the Young Investigator Grant of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2016Q03, 2016Q06), the ScientificResearch Project of the Development and Reform Commission of Hunan Province ([2013]1199), the Scientific Research Project of Science andTechnology Office of Hunan Province (2013SK2018), the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (2016JC2038), the XiangyaClinical Big Data System Construction Project of Central South University (45), the Clinical Scientific Research Foundation of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2015L03), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2017JJ3491, 2017JJ3492), the Postgraduate Independent Exploration and Innovation Project of Central South University (2018ts909), the Postgraduate Independent Exploration and Innovation Project of Hunan Province (CX2017B065), and the Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6750.17258).

Disclaimer: None of the authors have any financial and personal relationships with other people or organisations that could potentially and inappropriately influence this work and its conclusions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. . Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:635–46. 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. . EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1145–55. 10.1136/ard.2003.011742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. . OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raji AR, Bowden RE. Effects of high peak pulsed electromagnetic fields on degeneration and regeneration of the common peroneal nerve in rate. Lancet 1982;2:444–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uckun FM, Kurosaki T, Jin J, et al. . Exposure of B-lineage lymphoid cells to low energy electromagnetic fields stimulates Lyn kinase. J Biol Chem 1995;270:27666–70. 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dibirdik I, Kristupaitis D, Kurosaki T, et al. . Stimulation of Src family protein-tyrosine kinases as a proximal and mandatory step for SYK kinase-dependent phospholipase Cgamma2 activation in lymphoma B cells exposed to low energy electromagnetic fields. J Biol Chem 1998;273:4035–9. 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kristupaitis D, Dibirdik I, Vassilev A, et al. . Electromagnetic field-induced stimulation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 1998;273:12397–401. 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Mattei M, Caruso A, Pezzetti F, et al. . Effects of pulsed electromagnetic fields on human articular chondrocyte proliferation. Connect Tissue Res 2001;42:269–79. 10.3109/03008200109016841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ay S, Evcik D. The effects of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatol Int 2009;29:663–6. 10.1007/s00296-008-0754-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bagnato GL, Miceli G, Marino N, et al. . Pulsed electromagnetic fields in knee osteoarthritis: a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Rheumatology 2016;55:755–62. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer G, Pelka R, Barovic J. Adjuvante Behandlung der Gonarthrose mit schwachen pulsierenden Magnetfeldern. Aktuelle Rheumatologie 2006;31:226–33. 10.1055/s-2006-927051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanat E, Alp A, Yurtkuran M. Magnetotherapy in hand osteoarthritis: a pilot trial. Complement Ther Med 2013;21:603–8. 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee J, Park J, Sheen D, et al. . The Effect of Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Report of Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Randomized Trial. J Korean Rheum Assoc 2004;11:143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nelson FR, Zvirbulis R, Pilla AA. Non-invasive electromagnetic field therapy produces rapid and substantial pain reduction in early knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind pilot study. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:2169–73. 10.1007/s00296-012-2366-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicolakis P, Kollmitzer J, Crevenna R, et al. . Pulsed magnetic field therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee--a double-blind sham-controlled trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2002;114(15-16):678–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pipitone N, Scott DL. Magnetic pulse treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Curr Med Res Opin 2001;17:190–6. 10.1185/03007990152673828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sutbeyaz ST, Sezer N, Koseoglu BF. The effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of cervical osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. Rheumatol Int 2006;26:320–4. 10.1007/s00296-005-0600-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tejero Sánchez M, Muniesa PM, Díaz SP, et al. . Effects of magnetotherapy in knee pain secondary to knee osteoarthritis. A prospective double-blind study. Patología Del Aparato Locomotor 2003;1:190–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thamsborg G, Florescu A, Oturai P, et al. . Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with pulsed electromagnetic fields: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:575–81. 10.1016/j.joca.2005.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trock DH, Bollet AJ, Markoll R. The effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and cervical spine. Report of randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trials. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1903–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dündar Ü, Aşık G, Ulaşlı AM, et al. . Assessment of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy with Serum YKL-40 and ultrasonography in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 2016;19:287–93. 10.1111/1756-185X.12565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ozgüçlü E, Cetin A, Cetin M, et al. . Additional effect of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy on knee osteoarthritis treatment: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:927–31. 10.1007/s10067-010-1453-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Negm A, Lorbergs A, Macintyre NJ. Efficacy of low frequency pulsed subsensory threshold electrical stimulation vs placebo on pain and physical function in people with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1281–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li S, Yu B, Zhou D, et al. . Electromagnetic fields for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD003523 Issue 12. Art. No.: CD003523 10.1002/14651858.CD003523.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fary RE, Carroll GJ, Briffa TG, et al. . The effectiveness of pulsed electrical stimulation in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, repeated-measures trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1333–42. 10.1002/art.30258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Higgins JPT, Green S, Browne KD. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: A Handbook. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated 2010. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zeng C, Li YS, Wei J, et al. . Analgesic effect and safety of single-dose intra-articular magnesium after arthroscopic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:38024 10.1038/srep38024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xie DX, Zeng C, Wang YL, et al. . A Single-Dose Intra-Articular Morphine plus Bupivacaine versus Morphine Alone following Knee Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e140512 10.1371/journal.pone.0140512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cui Y, Yang T, Zeng C, et al. . Intra-articular bupivacaine after joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e11325 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeng C, Wei J, Li H, et al. . Effectiveness and safety of Glucosamine, chondroitin, the two in combination, or celecoxib in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Sci Rep 2015;5:16827 10.1038/srep16827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeng C, Li H, Yang T, et al. . Electrical stimulation for pain relief in knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:189–202. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jüni P, Reichenbach S, Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: rational approach to treating the individual. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20:721–40. 10.1016/j.berh.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Scherer M, et al. . Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:580 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zeng C, Li H, Yang T, et al. . Effectiveness of continuous and pulsed ultrasound for the management of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:1090–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salomonowitz G, Friedrich M, Güntert BJ. [Medical relevance of magnetic fields in pain therapy]. Schmerz 2011;25:157 10.1007/s00482-010-1005-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCarthy CJ, Callaghan MJ, Oldham JA. Pulsed electromagnetic energy treatment offers no clinical benefit in reducing the pain of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006;7:51 10.1186/1471-2474-7-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ryang We S, Koog YH, Jeong KI, et al. . Effects of pulsed electromagnetic field on knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2013;52:815–24. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shamliyan TA, Wang SY, Olson-Kellogg B, et al. . Physical Therapy Interventions for Knee Pain Secondary to Osteoarthritis. Rockville (MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Valat JP, Lioret E. [Cervical spine osteoarthritis]. Rev Prat 1996;46:2206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilder FV, Fahlman L, Donnelly R. Radiographic cervical spine osteoarthritis progression rates: a longitudinal assessment. Rheumatol Int 2011;31:45–8. 10.1007/s00296-009-1216-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ciombor DM, Aaron RK, Wang S, et al. . Modification of osteoarthritis by pulsed electromagnetic field--a morphological study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:455–62. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00083-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chang CH, Loo ST, Liu HL, et al. . Can low frequency electromagnetic field help cartilage tissue engineering? J Biomed Mater Res A 2010;92:843–51. 10.1002/jbm.a.32405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Parate D, Franco-Obregón A, Fröhlich J, et al. . Enhancement of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis with short-term low intensity pulsed electromagnetic fields. Sci Rep 2017;7:9421 10.1038/s41598-017-09892-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022879supp001.pdf (283KB, pdf)