Abstract

Objective

To establish the views and experiences of healthcare professionals in relation to interventions targeted at them to reduce unnecessary caesareans.

Design

Qualitative evidence synthesis.

Setting

Studies undertaken in high-income, middle-income and low-income settings.

Data sources

Seven databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase, Global Index Medicus, POPLINE and African Journals Online). Studies published between 1985 and June 2017, with no language or geographical restrictions. We hand-searched reference lists and key citations using Google Scholar.

Study selection

Qualitative or mixed-method studies reporting health professionals’ views.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two authors independently assessed study quality prior to extraction of primary data and authors’ interpretations. The data were compared and contrasted, then grouped into summary of findings (SoFs) statements, themes and a line of argument synthesis. All SoFs were Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) assessed.

Results

17 papers were included, involving 483 health professionals from 17 countries (nine high-income, six middle-income and two low-income). Fourteen SoFs were identified, resulting in three core themes: philosophy of birth (four SoFs); (2) social and cultural context (five SoFs); and (3) negotiation within system (five SoFs). The resulting line of argument suggests three key mechanisms of effect for change or resistance to change: prior beliefs about birth; willingness or not to engage with change, especially where this entailed potential loss of income or status (including medicolegal barriers); and capacity or not to influence local community and healthcare service norms and values relating to caesarean provision.

Conclusion

For maternity care health professionals, there is a synergistic relationship between their underpinning philosophy of birth, the social and cultural context they are working within and the extent to which they were prepared to negotiate within health system resources to reduce caesarean rates. These findings identify potential mechanisms of effect that could improve the design and efficacy of change programmes to reduce unnecessary caesareans.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017059455.

Keywords: caesarean section, over treatment, qualitative evidence synthesis, health professionals

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our sensitive search strategy optimises the likelihood that we have identified relevant studies published in the time period in principal journals in English and other languages.

Our findings were derived from obstetricians, midwives and general practitioners from high-income, middle-income and low-income countries and countries with both high and low rates of caesarean section.

Quality scores for included studies were generally high or moderate. There was high or moderate confidence on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research measure for 11 summaries of findings.

We only had data from one Asian country (China), one Middle Eastern country (Iran) and one South American country (Nicaragua).

Introduction

Caesarean section (CS) can prevent deaths and serious complications in mothers and babies when indicated, but there is no evidence of benefit in the absence of clinical or psychological need.1–3 In 2015, the WHO published a new statement declaring that CS rates higher than 10% are not associated with reductions in mortality and can cause surgical complications, disability or death, particularly where safe surgery cannot be conducted.1 4 Recent figures suggest an average global CS rate of 18.6%, ranging from 6.0% to 27.2% in the lowest and highest income regions.5 Some countries,6 and some regions within countries,7 now have CS rates above 50%. The WHO statement1 is a call to action that resonates with other contemporary campaigns8 9 for the reduction of medical overdiagnosis and overtreatment, to promote quality care and to reduce iatrogenic damage and excessive healthcare costs.10 11

Debate in this area spans four decades.4 10 12 The highest burden of CS in all income contexts occur in Robson groups 1–5, which comprise women with singleton, term, cephalic pregnancies with or without a previous CS.13–15 Reported reasons for rising CS rates in these groups include maternal request and the preferences and practice patterns of health professionals.16–19 Surveys of obstetricians’ personal preferences for CS report rates as high as 46% among US obstetricians20 but less than 2% among Flemish,21 Norwegian22 and Dutch obstetricians.23 Practice patterns within and between countries vary.24 25 Reasons include convenience and ease of undertaking a CS, risk aversion, fear of litigation in societies with growing intolerance to imperfection and in which CS is seen as a protective strategy, financial incentives and a decline in training and skills to perform forceps and vacuum techniques.25–27 Healthcare professionals’ views of CS differ according to gender, profession and socioclinical environment and the dominant opinion of their relevant professional body (which can shift over time).

Existing campaigns to reduce unnecessary medical tests and treatments acknowledge that it is counterintuitive for many health professionals to accept that their practices may be unnecessary and that this may partly explain why interventions targeting healthcare providers have had limited or moderate success.10 28 29 Single or multicomponent interventions have been tested, including educational programmes and training to improve adherence to evidenced-based guidelines; second opinion policies; and audit, feedback and peer-review. However, health professionals’ views are largely missing. This is a gap because understanding motivations, values and fears is essential for effective change management. The qualitative evidence synthesis presented in this paper aimed to identify, appraise and synthesise what health professionals say about interventions targeted at them to reduce unnecessary CS.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative evidence synthesis using an interpretive, modified, meta-ethnography approach.30 The published protocol (online supplementary file 1)31 specified three objectives relating to: (1) educational interventions aimed at improving adherence to evidence-based clinical practices, (2) second opinion policies and (3) audit, feedback and peer-review (replicating the categorisation used in the Cochrane Review of non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary CS).28 29 A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist is provided as online supplementary file 2.32

bmjopen-2018-025073supp001.pdf (106.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025073supp002.pdf (114.2KB, pdf)

Systematic searches were conducted in March and April 2017 in CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase, Global Index Medicus, POPLINE and African Journals Online. Search strategies were developed for each database using guidelines developed by the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group33 34 and strategies for optimising the identification of qualitative studies in specific databases (example search strategy online supplementary file 3).35–38 No geographic or language restrictions were imposed. Studies from 1985 onwards were included, as this was the publication date of the first WHO statement on appropriate childbirth technology.4 The reference lists of eligible studies were back and forward checked.39 40 Key articles cited by multiple authors (citation pearls) were checked on Google Scholar.28 29 39–41 The authors of relevant published protocols were contacted.42 43

bmjopen-2018-025073supp003.pdf (181.1KB, pdf)

Two review authors (CK and SD) independently assessed each abstract for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were studies: using a qualitative design or mixed methods that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis; in any setting where an intervention has been developed, communicated, distributed or implemented and targets health professionals; published after 1985 onwards; in any language; and a full manuscript was accessible. Exclusion criteria included clinical interventions targeted at Robson groups 6–10. The full texts of all potentially relevant papers were retrieved and independently assessed by CK and SD and checked by APB. Three Chinese-language articles44–46 were assessed following translation into English by a native Chinese speaker. An additional two papers were identified after the completion of this screening process—one was included47 and one was excluded.48

We undertook a qualitative evidence synthesis using a modified meta-ethnography approach,30 comprising five stages: (1) familiarisation and quality assessment, (2) data extraction, (3) coding into summaries of findings (SoFs), (4) interpretative synthesis, including thematic analysis and creation of a line of argument synthesis and (5) Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) assessment of the SoFs (online supplementary file 4). In stage 1, quality assessment of individual studies was independently undertaken by two authors (CK and SD) using the criteria described by Walsh49 with studies graded as: A: no or few flaws: the study credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability is high; B: some flaws: unlikely to affect the credibility, transferability, dependability and/or confirmability of the study; C: some flaws that may affect the credibility, transferability, dependability and/or confirmability of the study; and D: significant flaws that are very likely to affect the credibility, transferability, dependability and/or confirmability of the study. While no studies were excluded based on the quality assessment, these assessment scores were used when judging the relative contributions of each study in the development of explanations and relationships between studies. In stage 5 of the synthesis, these quality scores were also contributory to the CERQual assessment process. GRADE-CERQual is an approach to assess the confidence in qualitative evidence synthesis findings.50 51 Assessment was undertaken at the level of the SoFs, with each one assessed for four criteria: methodological quality of studies underpinning the SoF, coherence across those studies, relevance to the review question and adequacy. Based on the GRADE approach, each SoF was initially given a high confidence rating, and then downgraded to moderate, low or very low confidence depending on the degree to which each of these criteria were not met. Peripheral studies that were theoretically relevant to the general topic, but that did not meet the full criteria for inclusion, were used to test the line of argument ‘fit’ (online supplementary file 5).

bmjopen-2018-025073supp004.pdf (691.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025073supp005.pdf (451.1KB, pdf)

Reflexivity is a key component of qualitative research.52 CK, a medical sociologist, came to the project with prior beliefs about the complexity and interdependency of social factors driving CS rates, principally informed by undertaking earlier primary research with women and health professionals in the UK.24 53 SD, a professor of midwifery, has experienced the barriers clinical staff encounter when they try to use their clinical judgement and skills alongside personal values and knowledge of the current evidence base, and the views and choices of childbearing women, to decide if a particular test or treatment is appropriate for a particular mother and/or baby, rather than just applying the same rules to all regardless of need or choice. APB is a medical officer with over 15 years of experience in maternal and perinatal health research and public health and has witnessed the sense of helplessness and the barriers governments experienced when trying to reduce unnecessary CS.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or conduct of this review.

Results

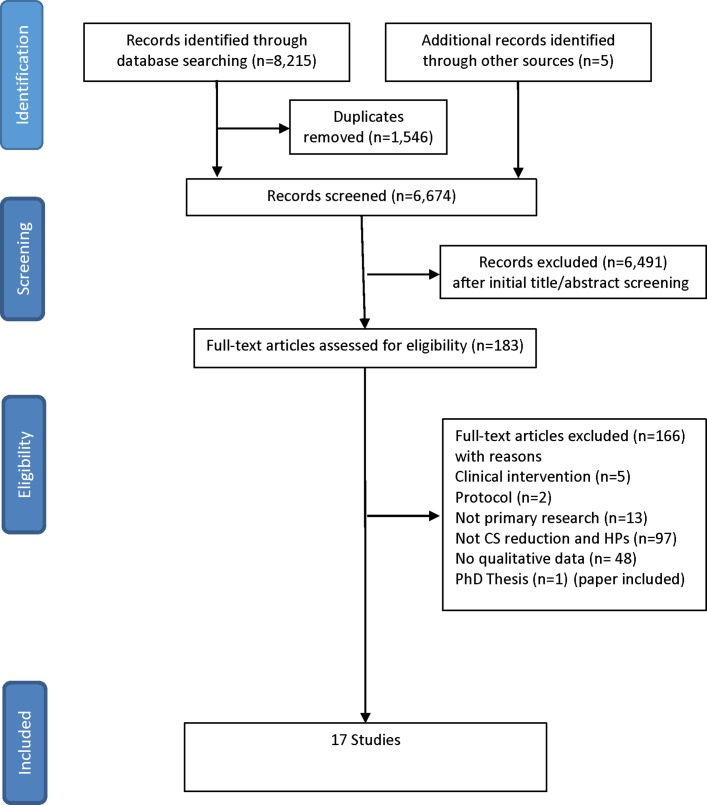

Seventeen studies were included from 17 countries in all WHO regions except Southeast Asia (Australia, Canada, China, Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, The Netherlands, Nicaragua, Sweden, Tanzania, Uganda, UK and USA).44–47 54–66 Studies encompassed countries with the highest and lowest CS rates globally and from high-income, middle-income and low-income settings5 (see figure 1). Individual studies included between 9 and 71 health professionals. Ten studies were graded A or B for quality. Six were graded C, and one was graded D. Two studies undertaken alongside randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified. Both were excluded. One was not focused on CS.48 The other did not use qualitative methods.67 Six included studies focused on health professional’s views in relation to clinical practice guidelines47 55 58 and change initiatives.57 59 62 Eleven explored barriers and facilitators to CS reduction more generally, and reported data relating to guidelines, policy initiatives, second opinion strategies, audit, feedback and peer-review.44–46 54 56 60 61 63–65 Seven studies had an explicit focus on vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC).54 56 58 62 64–66

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram. CS, caesarean section.

Table 1 details the characteristics of included studies and their quality assessment grade. Table 2 reports the SoFs, along with their CERQual50 51 ratings. The more detailed summary of evidence profile table is available as an online supplementary file. Fourteen SoFs statements were derived. They mapped onto three distinct themes (table 3): philosophy of birth (four SoFs); social and cultural context (five SoFs); and negotiation within the system (five SoFs). Additional quotes are provided in box 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies and quality assessment

| Author | Aim | Country (region) | Resource | Setting | Number of participants | Type of participant | Method | Quality assessment |

| Melman et al 47 | To explore barriers and facilitators for delivering optimal care as described in clinical practice guidelines. | The Netherlands (European) | High | Rural and urban | 30 | Obstetricians and midwives | Telephone interviews and focus groups | B |

| Foureur et al 66 | To explore the views and experiences of providers in caring for women considering VBAC. | Australia (Western Pacific) | High | Urban | 18 | Obstetricians and midwives | Semistructured interviews | B |

| Lundgren et al 65 | To explore the views of clinicians from countries with low VBAC rates on factors of importance for improving VBAC rates. | Ireland, Italy and Germany (European) | High | Rural and urban | 71 | Obstetricians, midwives, neonatologist and GP. | Focus groups | A− |

| Lundgren et al 64 | To investigate the views of clinicians working in countries with high VBAC rates on factors of importance for improving VBAC rates. | Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands (European) | High | Rural and urban | 44 | Obstetricians and midwives | Interviews and focus groups | A− |

| Litorp et al 63 | To explore obstetric caregivers’ rationales for their hospital’s CS rate to identify factors that might cause CS overuse. | Tanzania (African) | Low | Urban | 32 | Obstetricians and midwives | Observation, interviews and focus groups | A |

| Marshall et al 62 | To evaluate the ‘Focus on Normal Birth and Reducing Caesarean section Rates’ programme. | UK (European) | High | Rural and urban | 16 | Obstetricians and midwives | Semistructured interviews | B |

| Colomar et al 61 | To assess opinions of the determinants of the high rate of caesarean births in Nicaragua as well as possible barriers to and facilitators of optimal caesarean birth rates. | Nicaragua (Americas) | Middle | Unclear | 17 | Doctors and obstetric decision makers | Focus groups | A |

| Lofti60 | To explore effective strategies to reduce caesarean delivery rates in Iran. | Iran (Eastern Mediterranean) | Middle | Unclear | 10 | Obstetricians and midwives | Semistructured interviews | C |

| Dunn et al 59 | To reduce high rates of ERCS <39 weeks across the Eastern Ontario region. | Canada (Americas) | High | Unclear | 9 | Nursing cirectors and managers | Key informant interviews | C |

| Wang and Ding46 | To explore reasons for obstetric medical staff choosing CS for themselves in the absence of medical indication. | China (Western Pacific) | Middle | Urban | 11 | Health professionals | Semistructured interviews | C |

| Liu et al 45 | To explore affecting factors of continuing increase in CS rate in rural area. | China (Western Pacific) | Middle | Rural | 9 | Health professionals | Focus groups | C |

| Cox58 | To explore the barriers associated with the ACOG VBAC guidelines. | USA (Americas) | High | Rural and urban | 24 | Obstetricians, midwives and an administrator | Semistructured interviews | A- |

| Yazdizadeh et al 57 | To identify barriers to reduce the CS rate in Iran, as perceived by obstetricians and midwives as the main behavioural change target groups. | Iran (Eastern Mediterranean) | Middle | Urban | 26 | Hospital directors, obstetricians and midwives | In-depth interviews | A− |

| Wanyonyi et al 56 | To determine perceptions on the practice of VBAC among maternity service providers in East Africa and possible solutions (including acceptability of evidence, guidelines, and audit). | Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Ethiopia (African) | Low | Unclear | 63 | Doctors and midwives | Semistructured questionnaire | C− |

| Chen et al 44 | To explore informed choice and autonomy of uterine-incision delivery making in China. | China (Western Pacific) | Middle | Urban | 51 | Health professionals | In-depth interviews | D |

| Chaillet and Dumont39 | To investigate obstetricians perceptions of clinical practice guidelines and to identify the barriers to, facilitators of, and obstetricians’ solutions for implementing these guidelines in practice. | Canada (Americas) | High | Urban | 27 | Obstetricians | Focus groups and semistructured interviews | C |

| Kamal et al 54 | To explore the views of health professionals on the factors influencing repeat CS. | UK (European) | High | Urban | 25 | Doctors and midwives | Semistructured interviews | A |

ACOG, American College of Obstetrician and Genecologists; CS, caesarean section; ERCS, elective repeat caesarean section; GP, general practitioner; VBAC, vaginal birth after caesarean.

Table 2.

CERQual summary of findings (SoFs)

| Review finding | Studies contributing to review finding | CERQual assessment | Explanation of confidence in the evidence assessment |

| Philosophy of birth | |||

| Beliefs about birth: across HIC and MICs health professionals reported varying beliefs about birth. These included a common approach to birth shared by obstetricians and midwives who valued the physiological process and worked effectively as a team to make it happen (recognising it as an empowering process for women and only intervening when medically necessary), to labour and vaginal birth as a fatally flawed physiological process with CS the preferable means to an end. This dichotomy of beliefs reflected competing ideologies of birth and shaped the importance individuals attached to CS rate reduction. In MIC, while some obstetricians who preferred CS made reference to perinatal mortality and morbidity gains, this was not the experience of the few female Chinese obstetricians who actually had CDMR, nor the preference of Iranian obstetricians who expressed concerns about having to deal with comorbidities caused by previous CSs. Beliefs were influenced by professional training, personal experience and practice setting. | 44–46, 54, 57–62, 64–66 | Moderate confidence | Thirteen studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Rich data from 14 countries across four geographical regions, high-income and middle- income levels and high and low CS rates. Reasonable level of coherence with uncertain confidence in LICs. |

| Beliefs about what constitutes necessary and unnecessary CS: some health professionals reported CS rates as determined by factors beyond their control (ie, uncertain obstetric history, unfolding obstetric circumstance and clinical indications), but between health professionals, there was no clear consensus as to what they believed to be clinical indications across time (ie, breech), place (ie, availability and access) and parity (ie, women with a previous CS). Some senior doctors and midwives expressed concerns that less experienced staff are more likely to perform CS based on vague indications and spoke favourably about wanting junior staff to consult them more for a second opinion. Other senior staff suggested second opinion policies only work where both doctors are in attendance at the hospital. While some residents also reported wanting improved communication, they feared seeking a second opinion would negatively impact their clinical credibility and career. | 47, 54–57, 63 | Low confidence | Six studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thin data, with major concerns about coherence across settings. |

| Beliefs about the evidence base surrounding caesarean section: health professionals’ views about research evidence varied. Most health professionals recognised that guidelines represent the national or international evidence base, which sensitised them to reflect on their practice, providing a potential mechanism for change. Most health professionals wanted more evidence of transferability to their own practice context, particularly in MIC and LIC contexts, where audit was not common. Not all health professionals believed available evidence to be valid, applicable to their practice or feasible to implement and spoke about keeping-up-to-date with the latest evidence as challenging. Across resource settings, obstetricians and midwives expressed concerns about evidence of risks associated with CS as incomplete. Some health professionals who valued guidelines were also very clear they took other factors into account in actual decision making (ie, interpersonal relationships and patient’s unique characteristics). | 54–55, 57–59, 61–64 | Moderate confidence | Ten studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Rich data from across three geographical regions but limited data from LICs. High coherence across HICs and MICs. Uncertain confidence in LICs. |

| Belief in need to reduce unnecessary CS and receptiveness to change: across resource settings, health professionals reported concerns about high CS rates and associated morbidity. In Iran and Tanzania, some health professionals spoke about colleagues who performed CS for non-medical reasons as contravening medicines underlying ethical principle to do no harm. In European settings, health professionals experienced interventions targeted to reduce unnecessary CS as most acceptable where this vision was shared within and between multidisciplinary groups. In the UK and Scandinavia, health professionals from organisations that achieved success in reducing rates had positive attitudes towards critical self-reflection (including audit, second opinion and continuing medical education) and felt supported by colleagues and opinion leaders. Across resource settings, health professionals acknowledged concerted action to reduce unnecessary CS as challenging but achievable and intrinsically rewarding where there was respect, accountability and shared responsibility to support women achieve a vaginal birth. | 54–55, 57–59, 61–64 | Moderate confidence | Nine studies with no to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from Europe. Only one study from African region contributed to this finding. High coherence. |

| Social and cultural context | |||

| Fear of blame and recrimination (including medicolegal concerns): across HIC, MIC and LICs health professionals reported fear of litigation as an important influence on their low threshold for performing CS (although no one had actual experience of litigation in LIC). Predominantly in North America, health professionals described medicolegal concerns as an underlying factor in non-compliance to guideline recommendations. Across urban and rural settings with or without 24 hours obstetrical and anaesthesia coverage, obstetricians and midwives weighed up the balance of professional identity risk with not intervening, a poor outcome ensuing and a medicolegal case against them. Also in North America, some obstetricians were opposed to second-opinion policies because of the difficulties in medicolegal responsibilities that could ensue. In North America, some European countries and Africa, midwives and obstetricians expressed concerns about threats to their professional identity and career prospects posed by internal audit and feedback. A few health professionals welcomed guidelines as providing a defendable basis for their practice, while other midwives and obstetricians were undeterred in their commitment to intervene only when necessary. | 45, 54–55, 57–58, 61, 63–64 | Moderate confidence | Eight studies, with no to moderate methodological limitations. Rich data from five countries. Moderate coherence. |

| Value attached to financial rewards associated with CS: some health professionals were outspoken about the economic incentives for CSs, particularly in private healthcare facilities. This included doctors in Tanzania, Iran, China and Nicaragua, as well as midwives in Iran and the USA. Some doctors considered CS to involve more work, which justified the payment; others blamed the system, while others still reported personally valuing this extra income. Some doctors, and midwives, were critical of insufficient monetary reward to staff labour and vaginal birth by comparison. | 45, 47, 55, 57–58, 60–61, 63 | Moderate confidence | Eight studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Rich data predominantly from middle-income countries. High coherence. |

| Preferences for CS as convenient: health professionals valued both the scheduling CS offers and the lesser time commitment it entails compared with labour and vaginal birth. Some health professionals described how CS was convenient for women too (for the same reasons), although others recognised while CS might be more convenient for them, it is not what every woman wants. | 46, 57–61, 63 | Moderate confidence | Seven studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Fairly rich data from two studies and convenience a theme in a third. High coherence. |

| Beliefs about women: across the world, health professionals reported women’s demand for a particular birth method as an important factor influencing rates of CS, NVD and VBAC. Some health professionals believed women now value CS as a consumer choice (available in public and private healthcare settings), others attributed increasing rates to women’s lower threshold for CS during labour. In HIC, MICs and one LIC (Tanzania), a few health professionals spoke about women’s innate ability to labour and birth as being diminished by rising BMIs, advanced maternal age, sedentary lifestyles and ‘western diseases’. Health professionals also perceived women as lacking in antenatal education, being influenced by their families and the plethora of information about birth available in the media and online. | 45–47, 54–61, 63–66 | High confidence | Fifteen studies with no to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from 15 countries, across five world regions, high-income, middle-income and low-income settings with high CSRs. High coherence. |

| Dysfunctional teamwork, within the medical profession and including the marginalisation of midwives: health professionals reported dysfunctional teamwork within and between professionals as an important barrier to reducing unnecessary CS rates. Medicine’s entrenched hierarchies, lack of communication between maternity and theatre staff and difficult relationships between obstetricians, midwives and family doctors were all spoken about. Some midwives and obstetricians spoke passionately about the marginalisation of midwives and their exclusion from birth as counterproductive. | 47, 55–63, 65 | Moderate confidence | Eleven studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from across resource settings. High coherence. |

| Negotiation within the system | |||

| Organisation of care: across the world, health professionals perceived the maternity care system as insufficiently resourced (human and material). Midwives and obstetricians reported where CS was an important source of revenue operating facilities were a priority, and facilities for labouring women were poor and inadequately staffed. | 47,55-59,61-63,65 | Moderate confidence | Ten studies with no to moderate methodological limitations. Thin data from 13 countries, and thick data from Iran. High coherence. |

| Beliefs about need for high-level infrastructures: health professionals in HICs who were supportive of VBAC were flexible in their interpretation of guidelines and used them and available technologies in a facilitative way. Other health professionals, predominantly from MICs and LICs, but some from HICs, expressed concerns that a lack of human and technological resource made guideline recommendations unworkable in practice. In HICs where 24 hours obstetrical and anaesthesia cover was available, some health professionals reported women were still refused a trial of labour. | 47, 54–66 | Moderate confidence | Fourteen studies with no to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from HICs and MICs. The finding may have higher confidence in settings where the level of resource is sufficient to sustain necessary CS. |

| Reluctance to change based on lack of training, skills or experience: some health professionals spoke about how preregistration and postregistration training has ill-equipped the next generation for a reduction in CS rates as they have little experience, competency or confidence in normal labour and vaginal birth. Others reported wanting specific training on recommendations to make them more acceptable in practice. Reasons for many health professionals lack of buy-in was multifactorial; see also organisation of care; beliefs about need for complex infrastructure; and beliefs about the clinical encounter and autonomous decision making. | 45, 47, 55–57, 59, 61, 65–66 | Low confidence | Nine studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from one study. Extent of coherence unclear. |

| Views about the format, content and delivery of interventions: a few health professionals spoke about the importance of the tone of guidance as facilitative of reflection, not dictatorial, judgemental or threatening, at the same time as being clear about the need for change by avoiding the use of words such as ‘should’, ‘developmental’ or ‘pilot’. Some health professionals described how important it was for local opinion leaders to endorse projects, and where external facilitators were involved they are ‘credible’ and ‘grounded’, exercised cultural humility and understand the challenges within specific practice settings. In some HICs, health professionals talked about multidisciplinary/interprofessional team involvement meaning representatives from medicine (obstetrics, anaesthesia and paediatrics), nursing and midwifery, allied health professionals, quality, health records and scheduling in secondary care. | 55, 57, 59, 61–63 | Low confidence | Six studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from one study. Extent of coherence unclear. |

| Beliefs about the clinical encounter and autonomous decision making: obstetricians and midwives’ views varied as to who they thought should have the final say in the decision to perform a CS. Some health professionals accepted a woman’s right to choose CS, many thought the decision should be shared, while others believed the decision could only be made by health professionals qualified to do so. Some health professionals expressed concern time constraints in practice limited their opportunities to facilitate informed decision making. Where teams had a shared approach, they reported informed decision making did happen and irrespective of who made the final decision everyone involved was reassured by the process. | 44–47, 54–55, 57–59, 61–64, 66 | Moderate confidence | Fourteen studies with no to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from HICs, MICs and one LIC. High coherence. |

BMI, body mass index; CS, caesarean section; HIC, high-income country; LICs, low-income countries; MICs, middle-income countries; VBAC, vaginal birth after caesarean.

Table 3.

Summary of initial concepts, emergent themes and final themes

| Initial concepts | Emergent themes/SoFs | Studies contributing to review finding | Final themes |

| Belief in a common approach to birth across obstetrics and midwifery | Beliefs about birth | 44–46, 54, 57–62, 64–66 | Underpinning philosophy of beliefs about birth informs both the importance health professionals attach to reducing unnecessary CS and the effectiveness of healthcare teams to do so with competing knowledge claims about what are clinically necessary and unnecessary CS across time, place and discipline used by health professionals to either endorse or dispute the value of CS per se. |

| Belief in value of physiological labour and vaginal birth | |||

| Belief in CS as progressive for birth | |||

| Doubts about the value of CS and concerns about comorbidities | |||

| Belief CS rate determined by factors beyond health professionals control | Beliefs about what constitutes necessary and unnecessary CS | 47, 54–57, 63 | |

| Ambiguity surrounding medical indications for CS | |||

| Views and experiences of seeking a second opinion | |||

| Evidence as mechanism for change | Beliefs about the evidence base surrounding CS | 54–55, 57–59, 61–64 | |

| Evidence as incomplete, unconvincing or not applicable | |||

| Views about guideline adherence and local audit | |||

| Belief CS rates are too high | Belief in need to reduce unnecessary CS and receptiveness to change | 54–55, 57–59, 61–64 | |

| Belief unnecessary CS is unethical, negligent practice | |||

| Positive attitudes towards guidelines, second opinion, audit and feedback | |||

| Fear of blame in event of poor outcome of NVD | Fear of blame and recrimination (including medicolegal concerns) | 45, 54–55, 57–58, 61, 63–64 | Social and cultural context exerts an important influence on health professional’s commitment to reducing CS rates. This includes fear of blame and medicolegal concerns, financial incentives and health professionals perceptions of women. |

| Fear of threat to professional identify and career progression | |||

| Fear of litigation | |||

| Value greater monetary reward associated with CS | Value attached to financial rewards associated with CS | 45, 47, 55, 57–58, 60–61, 63 | |

| Value scheduling CS and less time commitment compared NVD | Preferences for CS as convenient | 46, 57–61, 63 | |

| Perception women are changing | Beliefs about women | 45–47, 54–61, 63–66 | |

| Perceptions of what woman want | |||

| Belief women lack confidence in NVD | |||

| No team work within profession/not easy to listen to opinion of peers | Dysfunctional teamwork, within the medical profession and including the marginalisation of midwives | 47, 55–63, 65 | |

| Little or no cross-professional working | |||

| Marginalisation of MWs | |||

| Concerns about the organisation of care | Organisation of care | 47, 55–59, 61–63, 65 | Health professionals may negotiate health system factors in accordance with their underpinning philosophy about birth, women and medicine, where the level of resource is sufficient to sustain necessary CS should a clinical need arise. |

| Insufficient human resource | |||

| Need 24 hours anaesthetic cover | Beliefs about need for high-level infrastructures | ||

| Need 24 hours consultant cover | |||

| Need for more equipment | |||

| Challenges to need for technology | |||

| Belief strategy/intervention would not be effective | Reluctance to change based on lack of training, skills or experience | 45, 47, 55–57, 59, 61, 65–66 | |

| Preregistration and postregistration education does not prioritise NVD skills and training | |||

| Perception insufficient time to implement | |||

| Perception insufficient resources | |||

| Positive tone of intervention (reflective and facilitative) | Views about the format, content and delivery of interventions | 55, 57, 59, 61–63 | |

| Without fear of blame or threat to professional identify | |||

| Use of language (ie, not conditional verb tense – should) | |||

| Women’s right to choose CS | Beliefs about the clinical encounter and autonomous decision making | 44–47, 54–55, 57–59, 61–64, 66 | |

| Informed decision making too lengthy | |||

| Doctor’s decision takes precedence | |||

| Decision-making process with women |

CS, caesarean section; MWs, midvives; NVD, normal vaginal delivery; SoFs, summary of findings.

Box 1. Themes with supporting quotes.

Philosophy of birth

‘If somebody says that a woman needs a caesarean our senior midwives are prepared to say “why?” … we’re all working for the same thing’. (Obstetrician, UK Marshall, 2016:337)

‘It’s just kind of a personal philosophy, too. Otherwise you’d be too afraid to do anything’. (CNM, USA, Cox 2011:5)

‘We have a 60 or 65% CSR, but we must not only focus on the percentage of caesareans, but also on the percentage of children admitted to the NICU; the perinatal mortality rate here is low (0%–3%)’. (Nicaragua, Colomar 2014:2385)

‘With increase of caesarean section rate mortality of newborn and maternal mortality ratio remained low’. (China, Liu 2010)

‘As a doctor I don’t believe caesarean section is the best choice. Caesarean should be used as necessary’. (China, Chen 2008)

‘… we used to deliver breeches [vaginally] and we no longer deliver breeches’. (Doctor, UK, Kamal 2005:1056)

‘The mode of delivery in case of a breech presentation depends on the expertise of the obstetrician in attendance’. (Midwife, The Netherlands, Melman 2017:5)

‘Maybe they [residents] say that it was “fetal distress” but it was not fetal distress, it was “doctor’s distress” … [laughter]’. (Specialist, Tanzania, Litorp 2015:235)

‘Residents who perform the job, decide in favor of CS as soon as even a small problem is encountered…’. (Specialist, Iran, Yazdizadeh 2011:7)

‘Quality of care can put pressure on people to do what the clients want rather than what is clinical need’. (Midwife, UK, Kamal 2005:1057)

‘The discrepancy between the midwives’ and the specialists’ information is our main problem. We don’t believe in issues that the physicians accept as true’. (Midwife, Iran, Yazdizeh 2011:9)

‘Continuous CTG according to protocol is recommended. However, the difficulty with that is the risk for uterine rupture is 1:1000 and so very low…I am a little flexible in this’. (Obstetrician, Netherlands, Lundgren 2015:6)

‘If the woman is nulliparous, pregnant with a child that is expected to be large for gestational age and with a fetal head not engaged at term, it depends on her characteristics whether or not I will discuss a CS’. (Midwife, Melman 2017:3)

‘I went on and looked at CS rates throughout the country. And was quite disappointed to see how high some of them were really’. (Midwife, UK, Kamal 2005:1055)

‘We started looking at some of the CS, why are we doing them, discussing them in meetings, and these CS weren’t necessarily indicated’. (Obstetrician); ‘I do think we’ve made good progress with it, but I think it would be complacent if we sat here to say… there isn’t more work to do, because there’s always more work to do … to keep developing and improving the service. You know, it’s good today but tomorrow can be better…’. (Head of Midwifery, UK, Marshall 2016:335)

‘Despite the reduced number of pregnancies, women undergo surgeries due to various other reasons in which the adhesions caused by previous C-sections might become troublesome’. (Iran, Yazdizadeh 2011:6)

Social and cultural context

‘Obstetricians are in a constant fear of being sued, so they’re taking a path of least resistance’. (Doctor, USA, Cox 2011:5)

‘Your reputation is important. No one will give you a gold medal for a VBAC rate of 95% if you make one mistake’. (Ireland, Lundgren 2016:6)

‘I am coming towards retirement, I don’t want to go to court’. (Midwife, UK Kamal 2005:1058)

‘Our society has spent more time on teaching the process of suing rather than introducing the labor to the general public’. (Midwife, Iran, Yazdizeh 2011:5)

‘In the private sector, providers are reimbursed approximately $700 for normal childbirth and $1500 for CS, so the doctor prefers to perform a CS’. (Nicaragua, Colomar 2014:2388)

‘… Profit from CS surgery is much high than vaginal delivery’. (Healthcare provider, China, Liu, 2010)

‘The main problem with natural delivery is its unpredictability, as it may occur anytime and disturb the physician’s program’. (Specialist, Iran, Yazdiadeh 2011:4)

‘People don’t want to wait too long. Rather than waiting the whole night, they take a short-cut’. (Consultant, Tanzania, Litorp 2015:235)

‘We know that CS is not indicated in low-risk pregnancy, but to avoid the night pressure and the work during the night…’. (Colomar 2014:2385)61

‘Some of them (women), they just quite like a planned thing. They have the caesarean’. (Midwife, Australia, Foureur 2017:6)

‘It is requested a lot (CS)’. (Ob/Gyn physician, Nicaragua, Colomar 2014:2385)

‘In the end of the day, when they come to deliver, they are so weak, they cannot push the babies. So the patients themselves are the ones requesting for CS, because they cannot tolerate the labor pain’. (Resident, Tanzania, Litorp 2015:235)

‘… not following a healthy diet have reduced the capabilities of our girls in this regard [to undergo vaginal delivery]’. (Physician, Iran, Yazdiadeh 2011:10)

‘Inadequate information to mothers makes them fear labouring!…’. (Kenya, Wanyonyi 2010:338)

‘Sometimes it is the mother’s mother and her sister and all that out there [general agreement], I am afraid, I am reading this. And it is the Internet, its Dr Google’. (Ireland, Lundgren 2016:6)

‘You can never ignore the information a patient receives from a neighbour or a niece. That sometimes seems more important than the medical information you provide’. (Netherlands, Melman 2017:5)

‘You might enter into a situation of decision of unnecessary CS because of the, you know, friction with the midwives’. (Resident, Tanzania, Litorp 2015:236)

‘In our hospital, the residents are not allowed to independently consult the anaesthesiologist at night’. (Resident, The Netherlands, Melman 2017:5)

‘The GP is vital… If the GP will support you, then you are in business’. (Obstetrician, Ireland, Lundgren 2016:4)

‘There is a little more work to be done in primary care, with nursing assistants, with social workers… to create a little awareness of what a vaginal delivery is’. (Nicaragua, Colomar 2014:2388)

‘There is no joint meeting between the midwifery and obstetricians associations’. (Midwife, Iran, Yazdiadeh 2011:9)

‘Then the ACOG shift happened… So we had to stop doing them [VBACs]’. (CNM, USA, Cox 2011:7)

Negotiation within the system

‘In our hospital improved support during labour could reduce CS rates. However, we know upfront that an increase in staffing is not an option’. (The Netherlands, Melman 2017:6)

‘Nobody can tell what will happen during a trial of labour (TOL), so we should say that a TOL is possible, but only if we have staff who are not overworked and exhausted’. (Italy, Lundgren 2016:5)

‘It is not possible to promote physiologic delivery without spending on it’. (Midwife, Iran, Yazdiadeh, 2011:9)

‘We cannot monitor the foetus continuously… why try a scar’. (East Africa, Wanyonyi, 2010:338)

‘If the patient is given enough time, she may have a normal delivery, but as the risk of a uterus rupture is present during labor and we need a blood bank available, we perform an elective surgery’. (Ob/Gyn physician61)

‘Not everybody needs to be on CTGs and that they don’t need to be on beds and stuff like that…’. (Midwife, UK, Marshall 2016:337)

‘In the past few years many obstetricians have never had the opportunity to do a vaginal delivery’; ‘If you ask any of the midwives in our hospital, they attest that they have not conducted a natural delivery for years’. (Specialists and Hospital Director, Iran, Yazdiadeh 2011:4)

‘Nowadays we can see how the culture has affected the training of residents [junior obstetricians]. For residents, a previous CS means another CS. They have to be told that a woman can have a VBAC’. (Italy, Lundgren 201:5)

‘I think we should realize that we are the ones who have done them that way’ [trained residents in hierarchical structures where admonishment has made them reluctant to seek a second opinion] (Specialist, Tanzania, Litorp 2015:235)

‘The Toolkit was not dictatorial in nature but rather it enabled the team to decide ‘where as an organisation you wanted to be’. (Midwife); ‘… everybody had a greater awareness; consultants, registrars, SHOs, ultrasonographers, student midwives, student nurses, anaesthetists even came [to the meetings]. … they all bring a different perspective, and they also take credibility back to their own peer group’. (Midwifery Manager, UK, Marshall 2016:337)

‘Non-responsible personnel such as the head of the network and health officials in small provinces force young specialists to stay away from C-section’. (Specialist, Iran, Yazdizadeh 2011:4)

‘… A trial of labour should be offered to a woman with one previous transverse low-segment caesarean section. The use of conditional verb tense in the guideline has been identified as a potential barrier to adopting the recommendations, refusing any sort of obligation’. (Chaillet 2007:794)

‘“Developmental” or “pilot” project, and inviting rather than mandating participation’. (Dunn 2013:31159)

‘I’ll do it [CS]! Because she has already decided! Or she will go to someone else’. (Specialist, Tanzania, Litorp, 2015:235)

‘That’s about the same thing as if I decide how the plumber should place the pipes in my home, or if I should go on a long holiday abroad and beforehand go to the surgeon and say, can I have my appendix removed so I don’t get sick?’. (Midwife, Sweden, Lundgren, 2015:6)

‘I am very good at telling people what they don’t want, what they can’t have. What they mustn’t expect. I’m damned if I let somebody come and say, ‘I’m going to have something this way’ unless they are prepared to pay for it’. (Midwife, UK, Kamal 2005:1058)

‘We need time to be able to approach the patients [to talk about Labour and vaginal birth), and what we have in this hospital is lack of time; we are so overloaded that we usually give only 15 min per patient’. (Physician, Nicaragua, Colomar 2014:2388)

‘Time is a factor. But we have a “Towards Normal Birth” midwife who is [very available] to us’. (Midwife, Australia, Fourer 2017:6)

Theme 1: philosophy of birth

This theme encapsulates how the philosophy of birth expressed by both individuals and teams acts as a guiding principle underpinning the value health professionals’ attach to CS reduction, and, therefore, to interventions designed for this purpose. Underpinning beliefs regarding birth play out in everyday clinical practice, including which caesareans, if any, health professionals view as unnecessary; how available evidence is used; and receptiveness, or not to change.

Beliefs about birth

Across 13 studies44–46 54 57–62 64–66 from 14 countries varying beliefs about birth were reported. An interdisciplinary, cross-system shared belief in vaginal birth was a key mechanism to facilitating a common approach that could help women deliver vaginally, as typified by a midwife from the Netherlands: ‘it is very clear that the hospitals we work with are also very much advocates of VBAC in the same way we are’ (p. 4).64 In contrast, a specialist from Iran, where the CS rate was in excess of 40%, said ‘The general belief indicates that caesarean is better than vaginal delivery. The dominant paradigm says so’ (p. 4).57 Some health professionals in the review valued labour and vaginal birth as a physiological process. Others believed that labour and birth in general, or VBAC in particular, comes ‘with the big-risk of a very-bad outcome’ (p. 4).65 These individuals thought CS was a reasonable solution for many if not most women, even if they had some doubts about the safety of the operation.

Beliefs about what constitutes necessary and unnecessary CS and beliefs about the evidence

There was ambiguity surrounding what health professionals believe constitutes a definite clinical indication for CS. This varied across time (eg, changing views about the need for CS for breech presentation); place (the extent to which CS was available and accessible locally); or clinical history (ie, whether women with a previous CS should or should not have a repeat operation in a subsequent pregnancy).47 54–57 63 Health professionals chose the evidence they used to support their position.54 55 57–59 61–64 Evidence could provide an impetus for change, but not where it was viewed as incomplete, unconvincing or inapplicable.59 61 In Nicaragua, for instance, specific concerns were expressed about the relevance of available evidence because ‘Studies have shown that VBAC is a good option, but these studies have been done in developed countries where educated people space their pregnancies’ (p. 2385).61 The absence of very local evidence was used as a rationale for resisting change: ‘The truth is that we don’t have statistics of CS complications that might negatively influence the decision to perform a CS, like fatal-deadly outcomes or anything like that’ (p. 2388)61

Belief in the need to reduce unnecessary CS and receptiveness to change

Across resource settings, some health professionals54 55 57–59 61–64 acknowledged that some CSs ‘weren’t necessarily indicated’ (p. 334).62 and CS rates were in general too high.54 Participants from Iran and Tanzania raised specific concerns about ‘whether CS on demand in private patients should be considered malpractice’ (p. 235).63 and that ‘physicians should respect ethical rules’ (p. 6),57 rather than acceding to patient demand. Positive attitudes towards continuing professional education and development were important to reintroducing belief in vaginal birth. ‘We are strengthened by watching how happy the patients are when it works, and we have the experience of how excellently women give birth, so we are strengthened by this [experience] in our care of all the other [women]’ (p. 7).64 Health professionals from organisations that achieved success in reducing rates of CS worked in cultures that valued clinical audit, second opinion and/or continuing medical education as part of continuous quality improvement.59 62 As this head of midwifery in UK said, ‘we knew we had a problem, we knew what the issues were, actually addressing them was the challenge for us’ (p. 337).62

Theme 2: social and cultural context (five SoFs)

The second theme explores how social and cultural context exerts an important influence on health professional’s commitment to reducing CS or not. Resistance was influenced by fear of blame and recrimination, including fear of litigation for not intervening; the value attached to personal financial rewards associated with CS; and preference for CS as a convenient, efficient birth method that can be scheduled. This was contextualised by shifting beliefs about the inherent capacity or not of women to give birth safely if left to labour without technical intervention and the strength of professional teamwork in local contexts and as advocated in national guidelines.

Fear of blame and recrimination

In eight studies,45 54 55 57 58 61 63 64 health professionals reported feelings of fear associated with the risk of poor perinatal outcomes following vaginal delivery, threats to their professional identity arising from seeking a second-opinion and a general fear of litigation. They acknowledged that these prompted the early clinical decision to default to CS,55 57 58 61 as evident in this quote from a Nicaraguan specialist: ‘[The] number one priority… is the fear of medico-legal problems because we didn’t do a cesarean section’ (p. 2385).61 Within studies, resistance to defensive practice was also reported: ‘I just think it’s a bunch of crap that you have to change your practice when you know something is safe because somebody might sue you’ (USA midwife) (p. 5).58 Across most studies the extent of actual experience of a lawsuit was unclear. In a study from Tanzania, where fear of litigation was given as a rationale for medically unjustified CSs, no participant had personal experience of being sued.63 It seemed that the practice was more about defending against such a situation ever arising in the future: ‘If the woman went to CS and she comes out safe and the baby is safe, there is no very big harm in that. Despite that the indication was not appropriate… It is not so bad compared to if CS was supposed to be done and it was not done in time’ (p. 236).63

Value attached to financial rewards associated with CS

Some health professionals were outspoken about the economic incentives for CS, perceiving some practices to be tantamount to ‘selling caesareans’ (p. 6).58 While some doctors considered CS involved more work, justifying greater payment, others blamed financial incentives for CS, while others were open about valuing the extra income provided by undertaking CS.45 47 55 57 58 60 61 63 There were critical comments from both doctors and midwives relating to insufficient income for the time spent with labouring women, and for vaginal birth, by comparison with the time needed and financial rewards for undertaking CS. In Iran, it was suggested that the ‘the paying system should be changed completely. Paying physicians a definite salary rather than based on the number of cases they visit, would change the condition significantly’ (p. 4).57 However, another specialist in the same study said ‘I won’t do it (vaginal delivery), even if I’m paid 10 times more’ (p. 4).57 The balance of financial reward with the convenience of the operation is not clear, but favourable attitudes to these two factors were linked in several studies57 58 60 61 63 as evident in this quote, ‘with CS I minimise my time and I earn more!’ (p. 235).63

Preferences for CS as convenient

In seven studies,46 57–61 63 health professionals noted the convenience of CS compared with vaginal birth. For women with a previous CS, one community obstetrician in the USA said, ‘it’s easier to do a repeat C-section’ (p. 6).58, while another community obstetrician in the same study suggested, ‘it’s much easier for us to schedule a C-section, but if it’s [VBAC] something that the patient wants, then we certainly give them that opportunity’ (p. 6).58 In Iran, Nicaragua and Tanzania, the use of CS to avoid night pressures was acknowledged.57 61 63 One Iranian specialist was disinclined to ‘revisit my patient in the hospital at 10 pm to carry out a vaginal delivery’ (p. 4).57 In Nicaragua, another overburdened local-level provider said, ‘We know that cesarean section is not indicated in low-risk pregnancy, but to avoid the night pressure and the work during the night’ (p. 2385).61 Some health professionals believed that CS was more convenient for women, describing the availability of extended family support during birth, father’s work schedule and dates of deployment overseas for military families.59

Beliefs about women

In 15 studies, health professionals talked about women as key to rising CS rates for psychological, physiological and social reasons.45–47 54–61 63–66 Health professionals believed women are now less prepared for labour, less confident in their capacity to give birth vaginally and more likely to demand a CS due to inadequate antenatal education, increasing fear of vaginal birth and decreasing tolerance of labour pain, coupled with increasing rates of obesity, sedentary lifestyles and ‘western diseases’ (p. 235).63 There was also the suggestion ‘C-section is becoming more common and stylish these days’ (p. 11).57 What women want and why was perceived to be influenced by family and friends, the media and interactions with (other) health professionals.

Dysfunctional teamwork within the medical profession and the marginalisation of midwives

Unsupportive medical hierarchies, communication barriers and difficult relationships between specialists and residents, and midwives and doctors were perceived as contributing to high CS rates in all settings.47 55–63 65 In Ireland, support from the family doctor (GP) from the outset of a woman’s pregnancy was reported as crucial to the outcome of trial of VBAC: ‘If the GP will support you, then you are in business’ (p. 4).65 In Iran and the USA, midwives and obstetricians spoke passionately about the marginalisation of midwives and about the counterproductive effect of their exclusion from guideline creation57 and content.58 Midwives and residents mentioned the presence of strict hierarchies as troublesome barriers to optimal care for women.47 57 63 Where these strong hierarchical structures existed, and in contexts where junior medical staff expected to be scolded for unnecessary questions or for mistakes, specialists acknowledged that juniors were reluctant to seek their opinion.63

Theme 3: negotiation within the system (five SoFs)

The third theme captures how health professionals actively negotiate care within the health system and how this impacts on the effectiveness of interventions to reduce unnecessary CS.

Organisation of care

From all resource settings, health professionals expressed concerns that the current organisation of care in their country was insufficiently resourced.47 55–59 61–63 65 In LICs, peripheral hospitals were described as overcrowded, underequipped and understaffed,63 with not enough nurses or midwives to care for women during labour.56 In MICs, CS was acknowledged as a way to compensate for insufficient time for antenatal counselling, lack of emergency care,61 lack of labour facilities or a lack of midwives,57 as well as being convenient for physicians and a valued source of revenue for individuals or facilities.57 61 However, while staff shortages were reported in HICs,47 62 changes to the organisational culture of caring in the UK were reported to address CS rates without additional resource.62

Beliefs about the need for high-level infrastructures

In 14 studies, health professionals talked about the infrastructure required to provide safe care during labour and vaginal birth in general and VBAC in particular.47 54–66 The need for modern user-friendly equipment in hospitals was a recurrent concern in LICs.56 63 In HICs, all of the hospitals in one study reported using professional guidelines (ACOG) as the defining standard of care for VBAC.58 Professionals in the hospitals talked about how the mundane details of operationalising specific aspects of care made the difference between whether or not VBAC was actually achievable. Immediately available access to senior staff skilled in the provision of emergency care in one hospital meant ‘we cannot leave the facility’; in another, ‘within 10 min from the unit [labour and delivery]’; and another no ‘dedicated anaesthesia provider for L&D [labour and delivery] meant ‘we’re not able to offer a VBAC’ (p. 6).58

Training, skills and experience

Reluctance on the part of some professionals to implement guidelines or programmes targeted at them to reduce CS stemmed from insufficient training and experience or past experience of a bad outcome.45 47 55–57 59 61 65 66 Concerns were voiced about the younger generation of health professionals (residents and midwives) who were felt to be ill-equipped with the requisite skills in labour and vaginal birth.57 61 65 In an Iranian study, ‘residents learn[t] the process of natural delivery during the first year but by the time they have learned how to deal with physiologic labor, the year ends and a new unskilled group becomes responsible for the whole thing’ and ‘Many first year residents transfer mothers from labor rooms for a C-section as they need to learn C-section before entering the second year’ (p. 7).57 The importance of training in labour and vaginal birth before professional accreditation and continued professional development was evident. In two Canadian studies,55 59 obstetricians identified the importance of ‘educational workshops focusing on the recommendations in practice to make the guidelines more acceptable and useful to health professionals’ (p. 795).55

Views about the format, content and delivery of interventions

Health professional buy-in was a process that had to be continuously negotiated,55 57 59 61–63 59 62 without fear of blame or threat to professional identity.62 63 Health professionals also wanted the tone of guidance to be reflective, rather than dictatorial. Language mattered, in particular avoiding words such as ‘should’, ‘developmental’ or ‘pilot’.59 Some health professionals described how important it was for local opinion leaders to personally endorse projects.

Beliefs about the clinical encounter and autonomous decision making

Organisations that accept CS on maternal request have higher CS rates.62 Some health professionals reported that a woman’s preference for a CS greatly influenced their clinical decision making.45 61 In one study of three countries with high VBAC rates, it was believed that, while women should participate in decision making, only professionals can make the final decision, based on medical knowledge.64 Short appointments limiting the time available to discuss birth options and build a trusting relationship were reported in HICs,66 and inadequate postnatal debriefing after a woman’s first CS was believed to be associated with maternal choice for repeat CS.54 Where teams had a shared approach to the clinical encounter, informed decision making was more likely to happen irrespective of who made the final decision, and everyone involved was reassured by the process. This required time.44–47 54 55 57–59 61–64 66

Line of argument synthesis

Health professionals’ accounts revealed the synergy between their underpinning philosophy of birth (as inherently normal or pathological), their social and cultural context and the extent to which they were enabled and prepared to negotiate within the local health and cultural system context and resources to reduce CS rates. These values and preferences influenced their receptiveness to interventions and, potentially, the effectiveness of the intervention itself. Online supplementary file 6 represents this in a figure. The mechanisms of effect for change or resistance to change appeared to include prior beliefs; willingness or not to engage with change, especially where this entailed potential loss of income or status including the risk of litigation; and capacity or not to influence local community and healthcare norms and values relating to CS provision.

bmjopen-2018-025073supp006.jpg (361KB, jpg)

Discussion

This qualitative evidence synthesis identified fourteen SoFs, resulting in three core themes: (1) philosophy of birth (four SoFs); (2) social and cultural context (five SoFs); and (3) negotiation within system (five SoFs). The consequent line of argument was supported by the peripheral literature41 68–82 and includes three potential mechanisms of effect for change. These are: prior beliefs about whether labour and birth are fundamentally physiological or pathological; willingness or not to engage with changing local practice norms, especially where this entails potential loss of income or status; and capacity or not to influence local community and healthcare systems and structures relating to maternity care provision. Based on our CERQual assessments of all 14 SoFs, we have the most confidence in core theme 2, which shows how social and cultural context shape health professionals attitudes to change. Within theme 1, low confidence in the SoF reporting beliefs about what constitutes necessary and unnecessary suggests further exploration is warranted into the ambiguities surrounding what health professionals may classify as necessary and unnecessary caesareans.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first global qualitative evidence synthesis that addresses health professional’s views of specific interventions targeted at them to reduce unnecessary CS. Our sensitive search strategy optimises the likelihood that we have identified relevant studies published in the time period in principal journals in English and other languages. The findings included the views and experiences of obstetricians, midwives and general practitioners from high-income, middle-income and low-income countries and countries with both high and low rates of caesarean section. Quality scores for included studies were generally high or moderate. There was high or moderate confidence on the CERQual measure for 11 SoFs. However, we only had data from one Asian country (China), one Middle Eastern country (Iran) and one South American country (Nicaragua). All of these regions have very high rates of CS.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

In comparison with surveys of health professional practice, our qualitative review provides more nuanced explanations for why interventions designed to change health professionals practice may or may not work. For instance, a survey associated with a cluster RCT of Brazilian doctors’ perspective on seeking a second opinion strategy before undertaking CS found that around half of the participants thought the strategy might be effective locally, though far fewer thought this would be the case in private as opposed to public hospitals.67 Our review reinforces this finding but also provides more detailed insights into why this situation might occur, since it shows that seeking a second opinion brings fear of recrimination that could undermine professional identities and career progression, and it threatens loss of income, challenges power structures and risks exposing overuse of CS for financial gain. Our review also resonates with the findings of studies that interpret maternity cultures as being the outcome of social processes and practices, exposing the disjuncture between what is supposed to happen and what actually happens when national and international policy measures are implemented in local contexts.48 83–85 Our review further identifies the degree to which health professionals manipulate the kind of evidence they use to reinforce their arguments for or against action on high CS rates.83 This indicates that beliefs and values are the key arbiter of intention to change behaviour, regardless of the wider system pressures and despite knowledge of the evidence base.83 85 86 Our findings therefore reinforce arguments that simply providing good quality evidence to healthcare providers will not influence practice change.

Implications for clinicians and policy makers

The three mechanisms of effect we have identified are aligned with the three key domains of general behavioural change theory.87 88 This theory has a number of forms but, in general, it can be summarised as ‘my behaviour depends on what I believe is right to do; what is normal to do around here; and what is under my control to do’. Changing the behaviours of health professionals and policy makers therefore demands action in these three areas. First, health professionals need to believe that they, personally, are performing unnecessary CS and that physiological labour and vaginal birth has an intrinsic value. Second, healthcare providers need to be brought together in intraprofessional and interprofessional groups to discuss and agree how to change local norms about practice decisions in various labour and birth scenarios. This may include development of skills in self-reflection and targeted continuing professional education and development. Third, health professionals need to be enabled within their healthcare system to address barriers that include the relative status and power of various professional groups, the quality (or not) of clinician–patient relationships, medicolegal concerns, monetary gain and efficiency concerns. Evidence of the impact of changes in these three areas is currently emerging in China.89 The present review also suggests that while concerns about under-resourced maternity services are reported across high-income, middle-income and low-income countries, there are specific challenges and clinical implications of CS use in low-income and middle-income countries where antenatal care can be insufficient, the environment, equipment and care during labour may be inadequate and access to emergency care is limited.

Unanswered questions and future research

The potential mechanisms of effect arising from this study should be integrated with the findings from qualitative evidence synthesis reviews of the views and experiences of women and communities90 and of those working at the level of organisations, facilities and systems.91 The integrated mechanisms of effect should then be used to design implementation interventions to reduce the overuse of CS, based on participative and action-oriented research designs that involve all relevant stakeholders and that take account of local context. In settings where there are rapidly rising CS rates, and where there was lower confidence for the summaries of findings in this review (such as South Asia and South America), further in-depth qualitative studies are needed to establish how far our findings are applicable locally, before intervention programmes are introduced in such settings.

Conclusion

Change programmes for health professionals need to act on personal beliefs, local norms and control beliefs to be effective. This review provides detailed insights into the particular factors that enhance or resist reduction in unnecessary CS from the point of view of health professionals in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries from around the world, including those with both very low and very high rates of CS. For maternity care professionals, there is a synergistic relationship between their underpinning philosophy of birth, the social and cultural context they are working within and the extent to which they are prepared and able to negotiate changes to health system structures and resources. To maximise the chance of success, the proposed mechanisms of effect resulting from this study, and from parallel reviews of the views and experiences of service users and of those working at the level of organisations, facilities and systems, should be built in to future change programmes designed to reduce unnecessary CS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Qian Long for her native-tongue translation and interpretation of Chinese papers into English language. Newton Opiyo for his contributions to enhance the synergy between this qualitative evidence synthesis and the Cochrane Review of non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean section. M

eghan Bohren for continuing support and discussion about qualitative evidence synthesis and the GRADE-CERQual method for assessing confidence in findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: APB and CK designed the review with input from SD. CK and SD conducted the searches, identification and screening with agreement by consensus of all authors on final inclusions. CK extracted data, with CK and SD agreeing initial, emergent and final themes. All authors contributed to writing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the UNDP-UNFPA-Unicef-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, a cosponsored program executed by the WHO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This is a qualitative evidence synthesis. Original research data are contained in the included studies. Data interpretation is contained in the manuscript. Further information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. Geneva: WHO/RHR/15.02, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. . Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet 2010;375:490–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Souza JP, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, et al. . Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Med 2010;8:71 10.1186/1741-7015-8-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organisation. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet 1985;2:436–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller AB, et al. . The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148343 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MdC L. Nascer no Brasil: Inquerito Nacional sobre Parto e Nascimento, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boatin AA, Schlotheuber A, Betran AP, et al. . Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. BMJ 2018;360:k55 10.1136/bmj.k55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The BMJ. Too much medicine. https://www.bmj.com/too-much-medicine (accessed 27th June 2018).

- 9. Choosing wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/ (accessed 27 Jun 2018).

- 10. Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, et al. . Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet 2016;388:2176–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elshaug AG, Rosenthal MB, Lavis JN, et al. . Levers for addressing medical underuse and overuse: achieving high-value health care. Lancet 2017;390:191–202. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32586-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johanson R, Newburn M, Macfarlane A. Has the medicalisation of childbirth gone too far? BMJ 2002;324:892–5. 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robson MS. Classification of caesarean sections. Fetal Matern Med Rev 2001;12:23–39. 10.1017/S0965539501000122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pyykönen A, Gissler M, Løkkegaard E, et al. . Cesarean section trends in the Nordic Countries - a comparative analysis with the Robson classification. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:607–16. 10.1111/aogs.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vogel JP, Betrán AP, Vindevoghel N, et al. . Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e260–70. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70094-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Torloni MR, Betrán AP, Montilla P, et al. . Do Italian women prefer cesarean section? Results from a survey on mode of delivery preferences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:78 10.1186/1471-2393-13-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bettes BA, Coleman VH, Zinberg S, et al. . Cesarean delivery on maternal request: obstetrician-gynecologists' knowledge, perception, and practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:57–66. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000249608.11864.b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Munro S, Kornelsen J, Corbett K, et al. . Do women have a choice? care providers' and decision makers' perspectives on barriers to access of health services for birth after a previous cesarean. Birth 2017;44:153–60. 10.1111/birt.12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharpe AN, Waring GJ, Rees J, et al. . Caesarean section at maternal request--the differing views of patients and healthcare professionals: a questionnaire based study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;192:54–60. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gabbe SG, Holzman GB. Obstetricians' choice of delivery. Lancet 2001;357:722 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71484-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jacquemyn Y, Ahankour F, Martens G. Flemish obstetricians' personal preference regarding mode of delivery and attitude towards caesarean section on demand. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;111:164–6. 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00214-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Backe B, Salvesen KA, Sviggum O. Norwegian obstetricians prefer vaginal route of delivery. Lancet 2002;359:629 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07733-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Does van der J, Roosmalen van J. Obstetricians’ choice of delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol 2001;99:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lavender T, Kingdon C, Hart A, et al. . Could a randomised trial answer the controversy relating to elective caesarean section? National survey of consultant obstetricians and heads of midwifery. BMJ 2005;331:490–1. 10.1136/bmj.38560.572639.3A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Habiba M, Kaminski M, Da Frè M, et al. . Caesarean section on request: a comparison of obstetricians' attitudes in eight European countries. BJOG 2006;113:647–56. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grytten J, Skau I, Sørensen R. The impact of the mass media on obstetricians' behavior in Norway. Health Policy 2017;121:986–93. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Bengtson JM, et al. . Relationship between malpractice claims and cesarean delivery. JAMA 1993;269:366–73. 10.1001/jama.1993.03500030064034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]