Abstract

Objectives

The issue of gaining employment for those with mental illness is a growing global concern. For many in the young adult population, who are at a transitional age, employment is a central goal. In response, we conducted a scoping review to answer the question, ‘What are the barriers and facilitators to employment for young adults with mental illness?’

Design

We conducted a scoping review in accordance to the Arksey and O’Malley framework. We performed a thorough search of Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, ABI/INFORM, PsycINFO and Cochrane. We included studies that considered young adults aged 15–29 years of age with a mental health diagnosis, who were seeking employment or were included in an employment intervention.

Results

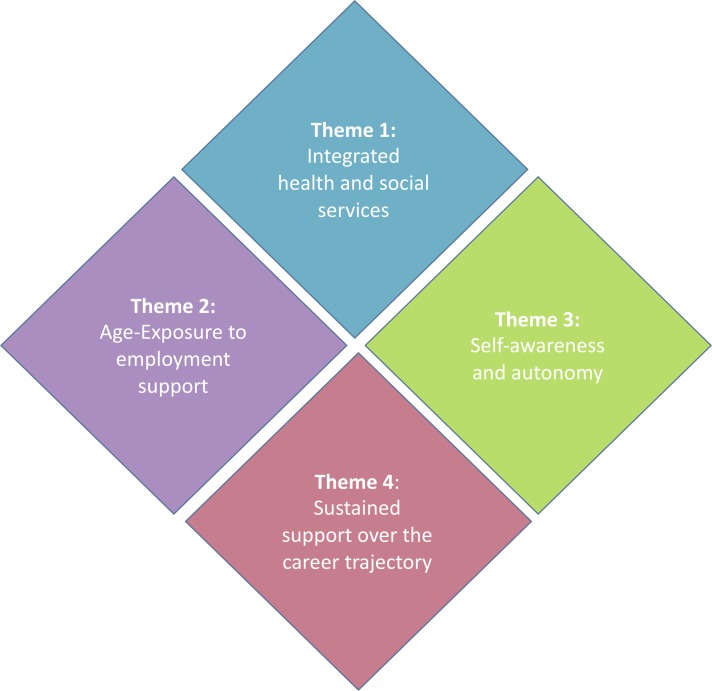

Our search resulted in 24 research articles that focused on employment for young adults with mental illness. Four main themes were extracted from the literature: (1) integrated health and social services, (2) age-exposure to employment supports, (3) self-awareness and autonomy and (4) sustained support over the career trajectory.

Conclusions

Our review suggests that consistent youth-centred employment interventions, in addition to usual mental health treatment, can facilitate young adults with mental illness to achieve their employment goals. Aligning the mental health and employment priorities of young adults may result in improved health and social outcomes for this population while promoting greater engagement of young adults in care.

Keywords: employment, young adults, scoping review, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Overview summary of the barriers and facilitators to employment for young adults with mental illness.

Wide scope of barriers and facilitators were reviewed.

Full-text review and data extraction completed by two reviewers.

Most studies had small sample sizes and lacked consistent measurement of outcomes.

Introduction

Mental illness is a widespread global challenge that affects approximately one in four young people at some point in their lives,1–3 with people aged 12–24 years experiencing the highest incidence of mental disorders of any age group.4 5 Adolescence and early adulthood are considered the peak periods for the onset of mental illness, with 75% of all diagnoses having an onset before the age of 25 years.6–8 Mental illness in young adults affects all education and income levels and all cultures.5 6 9 The global economic and societal burden of mental health disorders for this age group is rising at an alarming rate.9 10 Nevertheless, this age group has been shown to have the greatest challenge in accessing mental health services.11 12 Global mental health services have been described as ‘largely inadequate and unsuited to their [age-related] needs’.13 14 There is an international call to urgently re-examine how mental health services are delivered for youth.10 12 15–20 In order to reduce the impact of mental illness, and to increase the likelihood of recovery for young people, transformative change and service redesign are necessary.21

Recovery, in the context of mental healthcare and psychosocial rehabilitation, is defined as ‘the ability to live a full and meaningful life’.22 The greatest chance of recovery is associated with having an illness identified, receiving an intervention early and accessing ongoing support.9 15 21 23–25 One of the best indicators of recovery for adults with mental illness is the ability to obtain and maintain meaningful employment.11 26 High-quality studies have repeatedly shown that employment is associated with reductions in negative symptoms associated with a diagnosis of a mental illness, improvement in overall well-being and enhanced perception of social inclusion and self-worth.11 27–32 Yet approximately 70%–90% of people with a serious mental health condition are unemployed—this, despite increasing evidence suggests that the majority of them desire to work.33–35 Although limited research is available regarding how young adults with mental illness view employment as an outcome important for recovery, the promise of shifting towards what is important to youth and their families is now being emphasised.12 36–40 Employment may not only be a promising outcome for young adults in terms of symptomatic and functional recovery, but also a mechanism to engage young people who may not otherwise have sought support from mental health services.12

As research continues to emerge regarding timely integrated youth health services for young adults with mental illness,12 there is a strong case for mental health services to integrate employment-support components within the current model of service delivery.41–44 Incorporating employment into community mental health services for young adults may have a substantial impact at the individual, familial and societal level, thereby advancing health-related outcomes for this population.45 46 These impacts may include decreased hospital admissions, reduced interaction with the justice system, improved mental health and reduction of costs to the system.28 47 Yet, most often, health and employment services are offered in silos, inherently rigid systems that do not communicate and can increase the potential for poor quality patient experiences and outcomes. In order to strengthen the case for preparing youth with mental illness early on for employment, it is vital for researchers, clinicians and policy-makers to understand the barriers and facilitators to employment for the individuals and the system. This information will help communities strategise ways for health and social services to work together and meet the needs of young people and their families.

The aim of this work is to understand the barriers and facilitators to employment for youth with mental illness. In this study, we outline the breadth of knowledge available regarding obtaining and maintaining employment for young adults with mental illness and implementing employment programmes within mainstream mental health services.

Methods

Our scoping review drew on existing literature to understand what is known about the barriers and facilitators to employment for young adults with mental illnesses. As compared with systematic reviews, scoping reviews have a very broadly defined research question, include all study types, and track data according to key issues and themes.43 We followed a five-stage commonly used methodological framework48 to complete this review, including: (1) identification of the research question, (2) identification of all relevant studies, (3) selection of studies for detailed analysis, (4) charting of the data according to key concepts and (5) collation and summarising the findings of selected studies.

For the first stage of the scoping review, the research question that guided the review was: ‘What are the barriers and facilitators to employment for young adults with mental illness?’ In stage 2 of the review, a reference librarian was consulted in order to determine search terms, identify relevant databases, and build the search protocol with the team. Our team derived significant terms extracted from the research question and expanded on these terms to create a comprehensive list of primary search words and their variants, including ‘mental disorders’, ‘anxiety disorders’, ‘bipolar’, ‘dissociative disorders, ‘multiple personality disorder’, ‘mood disorders’, ‘personality disorders’ and ‘schizophrenia or psychotic disorders’, as well as a combination of the following work-related terms: ‘employment’, ‘employment, supported’, ‘unemployment’, ‘workplace’ and ‘occupation’ (see table 1). Combination of these terms were tested iteratively across the following databases on 28 July 2016: MEDLINE (1946–July 2016), ABI/inform (1986–July 2016), CINAHL (1982–July 2016), Embase (1974–July 2016), PsycINFO (1880–July 2016) and Cochrane (2005–July 2016) to allow for the identification of new combinations of terms or other related citations. In the late 1980s, frameworks for incorporating employment into health services for young adults with disabilities began to be consolidated in clinical practice.49–54 As a results, our scoping review search was limited to studies from January 1985 and beyond. We also searched Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms, MeSH tree and related terms found in keywords and article references, and truncation was used for maximum recall when applicable. All searches included at least one identifier for mental disorder linked to at least one identifier for employment. The initial cut-off day for this scoping review was 28 July 2016. A Google Scholar and Medline follow-up search was conducted on 1 October 2018, to ensure any new studies were included. Table 1 outlines the search strategy used in each database.

Table 1.

Search strategy terms used for each data-based searched

| Database(s) | Mental health search terms | Boolean | Employment search terms |

| Medline | 1. exp mental disorders or exp anxiety disorders or exp bipolar or exp dissociative disorders or multiple personality disorder or exp mood disorders or exp personality disorders or exp schizophrenia or psychotic disorders OR 2. Mental Disorder* or Adjustment Disorder* or Mental illness or Affective Disorders or Depression or Dysthymic Disorder* or Anxiety Disorder* or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD or Dissociative Disorder* or Multiple-Personality Disorder or Delusion* or Personality Disorder* or Psychotic Disorder* or Affective Disorder* or Bipolar Disorder* or Cyclothymic Disorder or Schizoaffective Disorder* or Paranoid Disorder* or Schizophrenia or Mood disorder* |

AND | 1. employment/or employment, supported/or return to work/or unemployment/or workplace OR 2. (((work or job) adj3 (site or place or location)) or worksite or workplace or job or work or employ*) |

| CINAHL and Psycinfo | 1. Mental Disorders OR Adjustment Disorders OR Mental Disorders, Chronic OR Affective Disorders OR Depression OR Dysthymic Disorder OR Anxiety Disorders OR Post Traumatic Stress Disorder OR Dissociative Disorder OR Multiple-Personality Disorder OR Organic Mental Disorders OR Delusions OR Personality Disorders OR Psychotic Disorders OR Affective Disorders OR Bipolar Disorder OR Cyclothymic Disorder OR Schizoaffective Disorder OR Paranoid Disorders OR Schizophrenia OR 2. Mental Disorder* OR Adjustment Disorder* OR Mental illness OR Affective Disorders OR Depression OR Dysthymic Disorder* OR Anxiety Disorder* OR Post Traumatic Stress Disorder OR PTSD OR Dissociative Disorder* OR Multiple-Personality Disorder OR Delusion* OR Personality Disorder* OR Psychotic Disorder* OR Affective Disorder* OR Bipolar Disorder* OR Cyclothymic Disorder OR Schizoaffective Disorder* OR Paranoid Disorder* OR Schizophrenia OR Mood disorder* |

AND | 1. worksite or workplace or ((work or job) n3 (site or place or location))or job or work or employ* OR 2. Employment OR Part Time Employment OR Temporary Employment OR Employment Status OR Unemployment OR 3. (Mental Health ‘Work’) |

| Cochrane Review and ABI/Inform | 1. Mental Disorder* or Adjustment Disorder* or Mental illness or Affective Disorders or Depression or Dysthymic Disorder* or Anxiety Disorder* or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD or Dissociative Disorder* or Multiple-Personality Disorder or Delusion* or Personality Disorder* or Psychotic Disorder* or Affective Disorder* or Bipolar Disorder* or Cyclothymic Disorder or Schizoaffective Disorder* or Paranoid Disorder* or Schizophrenia | AND | 1. employment or return to work or unemployment or workplace or job |

We included studies with employment-seeking young adults, aged 15–29 years, with a mental health diagnosis. This age group was chosen in order to best reflect the context of study and the challenges faced by those with an emerging mental illness who are attempting to seek paid work. We recognise, in many bodies of literature, youth are defined as 15–24 years of age.12 Many sources of peer-reviewed literature reference the 1981 United Nations report,55 where the secretary-general first referred to this age definition in a report to the General Assembly on International Youth Year (A/36/215, para. 8 of the annex)56 and endorsed it in ensuing reports (A/40/256, para. 19 of the annex).57 However, in the report,55 the secretary-general also highlighted that, ‘the meaning of the term ‘youth’ varies in different societies around the world’. For example, in Canada, most youth employment programmes are targeted for youth <30 years of age. As such, the definitions of age (<30) and each other aspect of the population (mental health status, gender, ethnicity) have been left broad in order to maintain a wide approach that generates a breadth of coverage of the topic.

For stage three of the scoping review, two research team members (TG and CB) independently screened all titles and abstracts of every study identified in the electronic search. We included all relevant articles published in English or French that described employment services for young adults with mental illness. In addition, we limited our search to human subjects and studies with young adults under 30 years old. The main qualifications that determined if studies were included in the relevant tables were: (1) the population was in the young adult age range of 15–29 years, (2) the population had a mental illness diagnosis and (3) the study had a primary focus on attaining employment. If all three of these criteria were addressed, the barriers and facilitators in the study were then examined and extracted. Country of origin and study format did not have any influence on determining relevance to this scoping review. We did not screen for methodology or levels of evidence.

In order to chart the data, we synthesised the studies and sorted each study according to key themes and ‘barriers and facilitators to employment’. Barriers and facilitators were sorted according to how they were specified in the article. If no such specification was available, three content experts (SB, LH, GL) with over 10 years of clinical experience were consulted to determine what category the theme should be placed. We charted data based on author, year of publication, study location, study type, intervention (if applicable), study population and key results (barriers and facilitators to employment).

Finally, we synthesised and sorted data according to key issues and themes to present a narrative account of the existing literature.48 Themes were categorised broadly. All team members reviewed the themes, and consensus was reviewed for the label of each theme. The main purpose of this scoping review was to identify the breadth of literature in this area of study, and whether there are any gaps in service identified within the subject matter. As a result, we did not complete an assessment of the quality of evidence, nor did we determine whether particular studies provide robust or generalisable findings.48

Patient and public involvement

This study is related to a prospective study currently under way that is examining the experiences of young adults participating in employment interventions (study Principal Investigator: SPB). The research question and data extraction variables for this study were informed by young adults participating in an existing employment programme in Vancouver, Canada. Two focus groups of eight youth, age 19–29, were invited to participate. Participants were recruited through a youth health centre in Vancouver called Foundry (foundrybc.ca), and the surrounding community. Results of this study will be presented to these participants (November 2018) in a modified world-café format. A 1-page summary of this project will also be developed and disseminated to the Foundry centres in British Columbia (n=7) and targeted policy and health services decision-makers.

Results

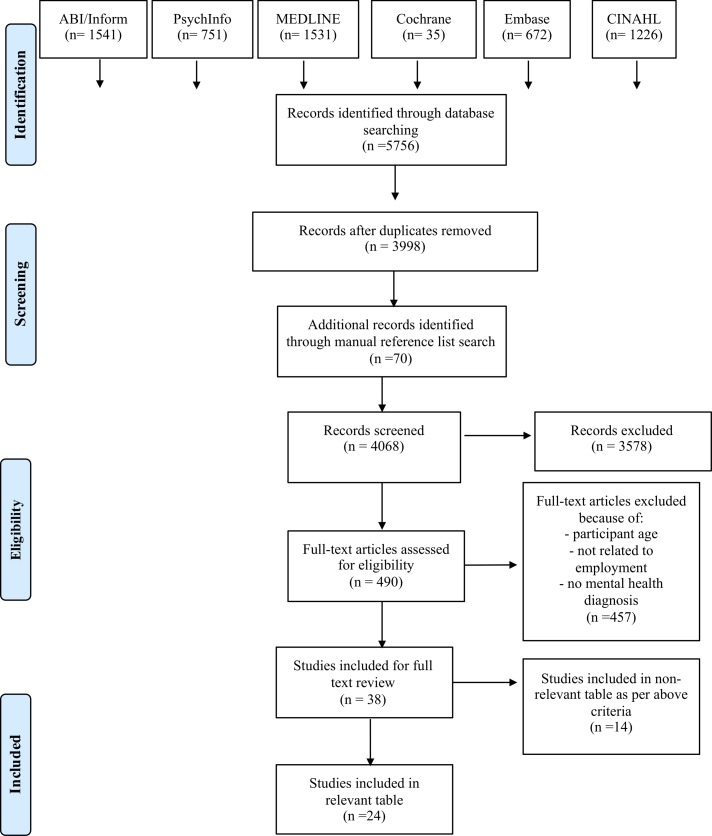

The initial search generated a total of 8037 results. After removing duplicates and performing a preliminary screen to ensure the inclusion criteria was met, a total of 488 titles and abstracts were identified. These were further screened to ensure that they addressed the appropriate age range, had a focus on employment, and that the participants had a diagnosis of a mental illness. As stated in terms of selection criteria, manual screening performed by the researchers generated a total of 33 articles that were carefully examined, and divided into relevant (n=19) and non-relevant studies (n=14). After the updated search from 2016 to 1 October 2018, we found an additional five articles now included in the review (total n=24 articles). Table 2 lists the relevant studies, and figure 1 describes the details for how we arrived at the final set of studies.

Table 2.

Details of included articles (n=24) including study origin, findings, barriers, facilitators and limitations

| Study information | Country | Population | Type of study and intervention (if applicable) | Summary of results | Facilitators to employment | Barriers to employment | Study limitations |

| Baksheev et al 43 | AUS |

Age: 15–24 Mean age: 21.4 years n=41 Diagnosis (Dx): first episode psychosis |

Randomised control study. Intervention: compared IPS plus treatment, with just treatment on its own. There was a 6-month intervention period and a 6-month follow-up period. |

Intervention group were 14.17 times more likely to have worked or studied during the 6-month assessment period compared with the control group. Intervention group were 16.26 times more likely to obtain work or study during the 6-month follow-up period. Baseline factors that were found to be not significant in determining if a participant would have found work or studied in the 6-month follow-up period included:

|

The main facilitator to employment was having participated in the IPS programme and not only the intervention as usual. Clinicians should not exclude any client based on ‘work readiness’, current symptoms or any other personal factors. |

No barriers to employment were identified in this paper. | Short follow-up (6 months). Small sample size. |

| Bassett et al 27 | AUS |

Age: 18–28 n=10 Dx: psychotic disorder |

Qualitative study. Intervention: focus groups on participants’ perceived barriers to employment. |

Themes of focus groups:

|

Programmes aimed to assist in the development of time management, stress management, self-confidence and problem-solving skills. Skills at how to manage the lifestyle change from not working to being employed. |

Low self-esteem. Low self- worth. Negative effects of medication (low motivation and tiredness). Lack of strategies to manage conflict/frustration. |

Small sample size. Only male participants included in this study. Participants were only from one health district. |

| Bond et al 62 | USA | NA | Systematic review of employment and education outcomes in early intervention programmes. | Incorporating well-defined evidence-based supported employment services into comprehensive early intervention programmes for patients in early psychosis significantly increases employment rates but does not improve educational outcomes compared with programmes lacking these services. | Early intervention Integrated employment services with early intervention services. |

Not specified. | Review did not did not meet the full standards of a PRISMA review. |

| Brimblecombe et al 15 | UK |

Age: 18–27 n=20 Dx: general mental health disorder |

Pre–post comparative treatment design. | Employment rates improved, although the sample size for this is very small. Cost-effective intervention. |

Early intervention Youth-specific mental health services. |

Unmet mental health needs. Lack of integration of services. |

Small sample size. Lack of control group. |

| Burke-Miller et al 41 | USA |

Age: 18–30* n=1272 Dx: any mental health dx |

Multisite RCT. Examined if participants had any kind of work, and if they were employed in a competitive job.† |

Youth (after intervention):

|

High future work expectations. Greater hours of supported employment services. - work history Positive work history (better able to provide references). Recovery focused. Younger age. Increased access to benefits counselling (for welfare). |

Heavy emphasis on job retention for youth. | Small sample size in the ‘youth’ category. |

| Dudley et al 42 | USA |

Age: 14–35 n=30 Dx: psychosis |

Naturalistic comparison of two studies. Intervention: IPS model+vocational worker. |

Improve the engagement in meaningful education, training or employment for young people with psychosis. | IPS. Younger age. Small caseload size for vocational therapist. Funding for vocational specialist. Zero exclusion policy for clients. Diversity of jobs developed. Jobs as transitions (positive experiences on the path of vocational growth and development). Follow-along supports (provided to employer and client on a time-unlimited basis). Rapid job searches (within 4 weeks). Ongoing work-based vocational assessments. |

Psychiatric illness. Lack of follow-up support. |

The findings rest on the assumption that the only difference between the services was the presence of the vocational worker. |

| Ellison et al 77 | USA |

Age: 18–35 n=36 Dx: any mental health diagnosis |

Longitudinal study comparing original intervention group and the same participants at 5 years’ follow-up.‡ | Data from two groups (original career education group, and follow-up group) were examined. The main significant differences were found between baseline (prior to original intervention) results and the follow-up 5 years later. Near significant decrease in proportion of participants currently in school or a training programme Findings indicate that positive results seen at the end of the original intervention period were maintained for the 5 years since that time. |

Higher work satisfaction | Decreased quality of life. | No control group. Not all original participants were located, therefore their data were not included. |

| Ferguson44 | USA |

Age: 18–24 Mean age: 21 n=28 Dx: homeless youth with any mental health diagnosis |

RCT. Intervention: supported employment with four components: (1) Vocational skills. (2) Small business skills. (3) Social skills. Clinical services. |

The study described a methodology for establishing a university-agency research partnership to design, implement, evaluate and replicate evidence-informed and evidence-based interventions with homeless youth with mental illness to enhance their employment, mental health and functional outcomes. | Vocational+clinical service integration. Structuring participant time. Social contact. Social identity. Zero exclusion from programme. Rapid job search. Younger age. |

No barriers addressed in study. | Majority of participants were male. Small sample size. |

| Ferguson et al 58 | USA |

Age: 18–24 n=20 Dx: homeless youth with any mental health diagnosis |

Pre–post Quasi-experiment. Intervention: adapted IPS model targeted at low-income youth. |

The study sought to adapt an evidence-based intervention for homeless young adults with mental illness. At follow-up, the IPS group were 7.83 times more likely of working than the control group. The IPS group worked 5.20 months compared with the control group at 2.19 months. |

IPS intervention. Less ‘severe’ mental health dx. Younger age. |

Living on the streets. Criminal activity. Drug use. The need to maintain personal hygiene. Securing transportation. Having enough food to eat. |

Majority of the participants were male. Small sample size. Non-random assignment to groups. |

| Gilmer et al 68 | USA |

Age: 18–24 n=74 Dx: any mental health diagnosis |

Qualitative study. Intervention: integrating employment services into mental health services. |

The study assessed the needs for mental health services for transition-age youths at youth-specific programmes. | Services that foster a transition to independence. Age-specific housing. |

Inconvenient scheduling. Weak patient–provider relationship. Limited programme funding. Lack of mentorship from peers experiencing similar struggles. Need for holistic approach to recovery. |

Sampling bias of transition-aged youth. |

| Haber et al 69 | USA | Mean age: 17 n=562 Dx: any mental health dx |

Descriptive | The most consistent improvement was shown on the indicators of educational advancement and employment progress. There was a post hoc improvement on employment/educational advancement. Productivity, education and employment all increased. |

Education for younger participants. Longer period of support for employment and education related goals for younger participants. |

Advanced age (within the youth population). | Lack of uniform data across sites on programme characteristics. Lack of control group. |

| Henderson et al 63 | CAN |

Age range: 12–24 n=690 Dx: youth not in employment or in education training (NEET) |

Cross-sectional. | NEET youth showed multiple psychosocial risk factors. They were also more likely to endorse substance use and crime/violence concerns than their non-NEET service-seeking counterparts. Gender-based differences were observed. | Integrated services. Working with schools. Working with employers to increase internship opportunities. |

Substance dependence. History of crime/violence. High level of need related to internalising and externalising behaviours. Gender-based differences. |

Participants not asked how long they were NEET. Study cross-sectional in nature. |

| Killackey, Jackson and McGorry45 | AUS |

Age range: 15–25 n=41 Dx: first episode psychosis |

Non-RCT. IPS+treatment as usual. |

65% of intervention group found employment compared with 9% of control group. The intervention group was able to find more jobs (23 compared with the control group’s 3). 80% of the intervention group listed welfare benefits as their primary source of income. |

Participation in a vocational intervention for young people. Acquiring jobs in a wide range of occupations that are congruent with personal interests and needs. |

Little or no work history can be a barrier to longer term employment. | Small sample size. No follow-up to determine whether a short 6-month intervention is sufficient to lead to lasting gains in employment and employment skills. |

| Lindsay64§ | CAN |

Age Range: 15–24 n=1898 Dx: teens with disabilities (all) |

2006 participation and activity limitation. | Severity of disability, type and duration of disability, level of education, gender, low income, geographical location and the number of people living in the household all influenced the kind of barriers and work discrimination for these young people. | High school diploma. Age (older +). More social capital. |

Low income. Geographical location. Family/friends discourage youth. Information about jobs is not adapted. Family responsibilities. Worry about isolation by other workers. Been victim of discrimination in the past Inadequate training. Inaccessible transportation. Lost income support. No jobs available. |

Dataset cross-sectional. |

| Luciano and Carpenter-Song73 |

USA |

Age: 22–32 n=12 Dx: psychosis substance use disorder |

Cross-sectional interview study Intervention: explored past/current participation experiences with school and work. |

This study examines the meaning and importance of career exploration and career development in the context of integrated treatment for young adults with early psychosis and substance use disorders. | Prioritising career oriented opportunities (not finding ‘just a job’). Optimism in developing a career. External support. Prioritising career-oriented opportunities. |

Family pushing for participants to obtain low wage/low skill jobs. Placement in job with no potential to advance. Decreased confidence. |

Data were cross-sectional, precluding causal interpretation. Study did not include:

|

| Nochajski and Schweitzer75 |

USA |

Age: 14–19 n=47 Dx: emotional+behavioural disorders |

Qualitative Intervention: school-to-work transition programme focusing on additional supports needed for youth. |

This study examines the transition of students with disabilities from high school to adult occupations, such as work and independent living. 30% of youth were still employed after the 10-week follow-up period. |

Transition programme starting in the beginning of high school. Pay youth to participate in specific programme. |

Unemployment of parents. Family living in poverty. Substance use within family. Incarceration of prominent family member. |

Only one diagnosis involved in study. Only youth enrolled in high school examined. Short follow-up period. |

| Noel et al 72 | USA |

Age: 16–24 n=280 Dx: psychiatric disorders |

Cross-sectional survey of young adults in IPS programmes. Intervention: IPS. |

Study team examined the barriers to employment for transition-age youth with disabilities enrolled in supported employment in eight community rehabilitation centres. Employment team members identified each youth’s top three barriers to employment using a 21-item checklist. |

Outreach of IPS team to the youth and the youth’s family. |

Lack of work experience, transportation problems and programme engagement issues.

Poor control of psychiatric symptoms. Families commonly discouraged their youth from employment. |

Small amount of missing data. Unable to explore demographic differences. |

| Porteous and Waghorn46 | New Zealand |

Age: 14–26 n=135 Dx: first episode psychosis (schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar affective disorder) |

Implementation of fidelity scale to determine effectiveness of supported employment services for young adults. | Occupational therapists and other allied health professionals can help facilitate system change towards the routine delivery of employment services integrated with public mental health treatment and care. | Colocation of employment services and publicly funded mental health services. Employment was identified as an unmet occupational need. Established in the early intervention team. |

Youth not being on the caseload for a mental health team. | Exploratory and anecdotal nature of study. |

| Rinaldi et al 59 | UK |

Age: 18–32 Median age: 21 n=40 Dx: first episode psychosis |

Pre–post study Compared baseline to 6-month follow-up and 12 month follow-up. |

Employment: Baseline: 10% were employed, 55% were unemployed. 6 months: 28% employed, 7% unemployed. 12 months:41% employed, 5% unemployed. Everyone employed at 6 months, continued to be employed at 12 months. |

Participation in vocational intervention programme. Team-based approach to recovery and employment. Proactively help participants retain and keep jobs. Welfare benefit advice. |

Not addressed in article. | Only diagnosis was psychosis. Small sample size. Lack of comparison group. |

| Rinaldi et al 83 | UK |

Age: 17–32 n=166 Dx: schizophrenia |

Pre–post design naturalistic evaluation Supported education was delivered. |

40% of participants were working/studying at start of intervention, this increased to 71% by 6 months. 47% of those who were unemployed at baseline, achieved open employment by 24 months follow-up. |

Transition from education/training to the labour market is critical for independence. Short work history is acceptable. Use of a ‘place and train’ method. |

Not addressed in article. | No control group. Quality of life was not explored. |

| Tapfumaneyi et al 61 | UK |

Age: 14–35 n=1067 Dx: any mental health dx |

Naturalistic study Intervention: multidisciplinary service that focused on recovery and relapse prevention for 2–3 years. |

After 1 year, 34.1% had been employed or studied towards a qualification. 61.2% were in employment. 50.4% were in educational courses employment/education at baseline. |

Reduction in duration of untreated psychosis. Engagement in early intervention services for more than 1 year (compared with those engaged for less than 1 year). Involvement in the IPS model. |

Welfare benefits (relatively high reward for being unemployed). Stigma, discrimination. Lack of professional help Illness related factors. |

Differences in outcomes between teams was not analysed. The study was not able to control for premorbid functioning. |

| Vander Stoep et al 67 | USA |

Age: 18–21 years n=181 Dx: anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, disruptive disorder |

Longitudinal study Compares 33 participants with psychiatric disorder and 148 participants without psychiatric disorder. |

39.4% of participants with psychiatric disorder had not completed secondary school (six times less likely than other youths to accomplish this task) 4.07 times less likely to be employed or in college/trade school. |

No diagnosis of psychiatric condition. | Diagnosis of a psychiatric condition. | Examined multiple areas of life: gainful employment, criminal involvement, sexual activity and secondary school completion. Small numbers hampered the ability to draw firm conclusions about the magnitude of the effects of exposure. |

| Veldman et al 71 | NDL |

Age: 11–19 n=1711 Dx: any mental health dx |

Prospective cohort study Intervention: Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey. |

Examines the aetiology and course of psychopathology. Study found that Mental health dx affect education and employment in negative ways. |

Being diagnosed with a mental illness later in life. | Mental health diagnosis indicated as a high-stable trajectory, meaning they had serious mental illness at a younger age compared with others in the population. | Measuring the outcome at the same time point as the end of the trajectory, allowing reverse causation. Limited number of young adults at work without basic education level and in neither education nor training. |

| Waghorn et al 60 | AUS |

Age: 15–25 n=7 Dx: any mental health diagnosis Socially and economically marginalised people |

Descriptive study. Intervention: supported employment. |

The study sought to determine what the major and minor barriers were when integrating supported employment services into already existing mental health services. | Setting clear goals throughout treatment. Establishing sustainable partnerships between the health and employment sectors. |

Time it takes to integrate vocational staff into mental health team. Lack of resources/funding for programming. Differences in organisational cultures. Legal, insurance and confidentiality issues. Large caseload size for employment specialists. Limited follow-up support. Having to participate in a programme while not working/being paid. Additional training to vocational staff from a mental health perspective. |

No clear number of population. |

*Divided into three groups: youth (18– 24), young adults (25– 30), older adult (31+).

†Definition of competitive job: pays minimum wage or higher, located in a mainstream/integrated setting, is not set aside for mental health consumers, is consumer owned.

‡Follow-up from Danley et al, 1992.90

§Lindsay study included young people with all disabilities.

AUS, Australia; CAN, Canada; IPS, individual placement support; NA, not applicable; NDL, Netherlands; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RCT, randomised control trial.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram outlining study selection.

Of the 24 relevant articles, 11 were from the USA, four were from Australia, four from the UK, two from Canada, one from New Zealand and one from the Netherlands. Results showed that a concentration on employment for young adults with mental illness is occurring, for the most part, in the Western world, with the USA being the focal area of research, primarily in the area of first episode psychosis and early intervention treatment. Of the 124 articles, 8 were published between 1999 and 2009, and 15 were published between 2010 and 2018. Although the search criteria allowed for articles published from 1985, the researchers were unable to identify any relevant articles from 1985 to 1998.

This scoping review identified several themes in regards to the barriers and facilitators to employment for youth with mental illness. As shown in figure 2, the four main themes extracted from the literature were: (1) integrated health and social services, (2) age-exposure to employment supports, (3) self-awareness and (4) sustained support over the career trajectory.

Figure 2.

Common themes found in the scoping review about the barriers and facilitators to employment for young adults with mental illness.

Integrated health and social services

The scoping review found that having an employment intervention in addition to usual mental health treatment led to higher success rates for young adults with mental illness15 42–44 58–64 (as identified in table 2). For example, one youth-tailored employment intervention resulted in 65% of the intervention group gaining employment, compared with only 9% of the control group.45 Two studies found that youth-tailored employment support, when delivered concurrently with conventional mental health therapies, led to improved health and employment outcomes.41 43 Porteous and Waghorn46 suggested that having both interventions (health and employment) in the same physical site mutually reinforced these successes.

Throughout many of the studies reviewed, the two central frameworks often identifed when addressing employment outcomes for youth were the recovery-oriented framework and the biomedical model. The biomedical model was defined as physical or biological aspects of disease and illness. In these studies, success was achieved when there is an absence of the disease and/or disorder or improvement in symptomology.65 In contrast, the recovery model focuses on ‘living a satisfying, hopeful, contributing life, despite psychiatric disability or symptoms’. (Piat et al, p168)66 Our results suggest that the paradigm used to guide intervention and care may shape how young adults gain and maintain employment. For instance, two studies highlighted that the biomedical model was a major barrier to finding employment for this population,46 67 and three studies suggested that the recovery-oriented framework was a facilitator to increased rates of employment for young adults, based on its holistic perspective of physical, mental, social and spiritual health.41 59 68

Age-exposure to employment support

While the literature is still growing for this population, the scoping review found many suggestions that age-exposure to employment-related interventions was critical to employment success and sustainability. Studies in this review suggested that earlier exposure to employment programming was associated with improved long-term employment outcomes and more engagement from youth in other areas of treatment and rehabilitation.41 42 44 46 58 61 63 69 70 Some studies also emphasised that in addition to early employment intervention, early diagnosis of a mental illness was also essential to ensure that young adults have access to the full range of treatments and interventions needed to optimise their potential to self-manage with their condition and thrive in the community.15 63 71 The review also highlighted a need to include and reach out to families and social networks early. Family and friends were reported in two studies as discouraging youth from employment, and thereby acting as barriers.64 72 73

One of the main temporal issues that was discussed across several studies was the focus on ‘finding a job’ as opposed to seeking a ‘long-term career’. The goal of finding a career was described in the literature as a potential barrier and not always applicable to this age group.41 68 Some studies in the review highlighted that youth felt many existing programmes were too focused on ‘getting a job’ rather than supporting milestones along journey of employment and career construction.60 74 The results of this review yielded a concentration of studies focused on supporting young adults to have a variety of skill development experiences, thereby helping a young adult achieve their goal of finding a first job.41 42 44 46 74

Self-awareness and autonomy

All studies collectively identified that seeking employment can be a challenging endeavour, especially for young adults doing so for the first time. For better chances of success in finding employment, studies in the review suggested that harnessing feelings of hope and optimism about themselves and their career prospects is vital to employment success.41 Some studies identified that young adults reported feeling more optimistic about jobs in which they can learn and progress, leading to greater senses of accomplishment and self-worth.41 74 One participant in study #2 described the impact of employment on self-esteem as:

“a vicious circle, ‘cause you don’t have any work and you don’t bring in an income and it gives you no self-esteem, and then you don’t want to get up and go get a job.” (Bassett et al, p68)27

Self-worth and self-esteem were identified throughout all studies as being important for this age group.

Our review also found that programmes allowing young adults to choose the jobs they pursued further empowered them to take control of their career goals and aspirations for the future, in addition to finding employment.42 44 The ability to choose was identified as a central asset for this age group: our review identified that, while many programmes focus primarily on the retention of jobs, the young people themselves do not always share this priority. Giving young adults the right to both choose and leave jobs, allowing them to explore career opportunities and pursuing opportunities to develop more skills, were key facilitators to job and career development for this population.41 44

Sustained integrated care

Sustained employment support was identified as a major barrier to short-term and long-term employment success for young adults. Many of the studies identified in this review did not continue to provide support for participants beyond their end of the job-seeking period.41–44 A short duration of support was identified as a major barrier for young adults with mental illness (ranging from 2 to 16 weeks). The scoping review highlighted that programmes with short follow-up periods were more likely than programmes with long follow-up periods to result in poor employment outcomes for youth.27 42 60 Although the studies reviewed are relatively recent, the data support the benefits of continued support to help youth with their employment goals.69 For example, a number of studies42 44 75 suggested that youth employment programmes may work best when focusing on the continued success of retaining employment and career development in general.44 68 76–78 Of critical importance, most studies in this review suggested that ongoing support to integrate both health and employment/career development goals, is a significant facilitator to ensure that young adults with have the capacity to gain the skills necessary to manage long-term employment.27 31 41 46 58 63 68 69 72 79

Discussion

This review describes the current literature related to the facilitators and barriers for young adults with mental illness who are seeking employment. A scoping review was chosen in order to determine the breadth of the literature for this topic. While there were no other systematic reviews or meta-analyses of the literature identified in this research area, this scoping review did identify a number of studies that investigated adults (age 29+) with mental illness who were seeking employment. These studies were excluded based on the allotted age range criteria. However, they nonetheless found similarities to the studies included as relevant in the scoping review, such as the importance of integrated support, sustained access to health and employment services that are not time-limited, and a focus on employment as a vehicle towards improved health outcomes.14 80 81

This scoping review identified 24 relevant articles, of which there were a number of methodologies, type of interventions and/or research questions. This disparity suggests that the literature in this field of study is still developing, and alludes to the diverse approaches taken to understanding the field. The articles were published between 1999–2018, with the majority (n=16) published between 2010 and 2018. The studies were predominantly completed in English-speaking countries (n=23) with a high volume from the USA (n=12), while others were completed in Australia (n=4), New Zealand (n=1) and the UK (n=4). Common facilitators included high self-efficacy,31 43 68 early intervention,27 41 46 68 69 participation in a supported employment programme,31 41 45 46 58 68 82 and a long-term follow-up after intervention.27 41 Barriers included the use of exclusion criteria,41 58 68 lack of social capital,61 64 75 stigma in the workplace,27 64 history of criminal justice involvement,44 58 inadequate training opportunities27 61 73 and lack of ongoing integrated funding for programming.27 68

Among these barriers, four overarching themes were identified in this review. These themes may add value to the way that employment and health services are currently designed and implemented for the young adult population. Our review emphasised that the transition from adolescence to adulthood is a typical process of development, but for many young adults with mental health conditions, this transition can be especially difficult.69 Most studies highlighted that young adults have unique needs that are different from those of older adults. Creating a programme designed specifically for this age group may allow professionals to better understand their needs, and provides opportunities to further young people’s professional development despite the barriers of mental illness. For the young adult population, retaining the same job may not be indicative of a successful employment pattern; rather, our review suggests that young people with mental illness may require the opportunity to explore various jobs in order to expand their skill set. Our review suggests that young adults with mental health conditions should be afforded the same opportunities as their peers by receiving tailored supported employment programmes designed to support their dynamic health and employment goals.41 Additionally, increasingly more studies emphasise that young adults should be involved in co-designing these integrated services so that they are centred on the needs of youth, rather than the system alone.12 40 Most studies in our review emphasised that long-term follow-up support is critical for this population to help them navigate the employment landscape. As youth acquire new jobs, they may also benefit from continued support throughout these subsequent transitions to maximise their success, self-esteem and overall well-being.

Our scoping review results support emerging literature that suggests that incorporating vocational interventions at the onset of illness can have both short-term and long-term effects, including the development of skills and interests, and a decrease in the likelihood of chronic unemployment which in turn can shape health outcomes.27 41–45 58 67–69 74 83 84 Our review did highlight notable heterogeneity in the interventions delivered; however, one common theme identified that supported employment intervention, when integrated with mental health treatment, may offer young adults an increased probability for employment success. More research is needed to outline evidence-based models of employment support for this group that can be integrated into existing health services. Such information will be important when helping youth learn to self-manage their illness while also achieving their employment goals.44 In addition, this information is critical to support policy decisions to fund employment interventions as core services for youth mental health services and programmes.

Another area of future research is to understand the components of supported employment interventions that can produce meaningful outcomes for youth. Our review identified a lack of standardisation for how these services have been developed and delivered. Further work in close collaboration with youth and key stakeholders is needed (ie, clinicians, family, funders) to tailor supported employment programmes that can be scaled across mental health services and can be delivered early in the care pathway.85 Given the increasing emphasis on patient-oriented research across developed countries,86–89 there is an ideal opportunity for future research in this area to be conducted in partnership with relevant stakeholders, notably youth. By working with youth research partners to develop and test such interventions, mental health services have the opportunity to foster evidence-informed healthcare by bringing innovative rehabilitation approaches to the point of care for young adults with mental illness.

While it is not the main tenet of a scoping review, it must be acknowledged that a thorough investigation into the quality of the literature was not completed. Despite the lack of analysis based on study rigour, our review did identify that many studies were descriptive in methodology, and did not include control groups. As well, most studies had small sample sizes and lacked consistent measurement of outcomes. In order to optimise decision-making, evidence from well-designed studies is needed to develop health services, guidelines and policies that apply to this young adult population. Such clarity around employment and integrated approaches to treatment may have significant potential to improve performance, accountability and innovation of youth mental health services worldwide.

In conclusion, the health and well-being of young adults with mental illness is a topic of global concern. Our review suggests that the employment goals of the young adult population are important to them, and therefore should be recognised by the mental health system as an area to address and improve upon. This paper presents preliminary evidence for the benefit of integrating employment intervention and mental health services, specifically highlighting the barriers and facilitators for this population to obtain employment. Collectively, the studies included in the review emphasise that it cannot be assumed that young adults can be sized into an adult model of care in relation to their employment and mental health needs; tailored programmes are required to address youth-specific needs. Aligning the mental health and employment priorities of young adults may enable efficiency in achieving improved outcomes for this population, while promoting greater engagement of young adults in care and accountability of mental health services worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is extended to Dr Letitia Henville, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of British Columbia, for editorial support.

Footnotes

TG and CB contributed equally.

Contributors: SPB is the senior and corresponding author. She has taken the primary responsibility for communication with the journal during the manuscript submission, peer review and publication process, and has ensured that all the journal’s administrative requirements, such as providing details of authorship, and gathering conflict of interest forms and statements, are properly completed, although these duties may be delegated to one or more coauthors. SPB has also designed the study, contributed to the writing of the manuscript and oversight of graduate student responsibilities to complete this work. TG and CBr conducted the scoping review, participated in data extraction and synthesis, and wrote the first draft of the paper for submission as their research project for completion of a Master’s degree in Occupational Therapy at the University of British Columbia. LH, GL, PB and SM contributed to the study design, search strategy, interpretation of study results and review of the manuscript. All four authors reviewed the accuracy and integrity of the work. All four authors provided specific content clinical expertise to inform the discussion and implications of the study results (from the perspective of occupational therapy, psychiatry and peer support). AL was the research coordinator on the project. She coordinated all aspects of the study, including drafting the protocol, acting as the byline between the library and the students, reviewing the first draft of the manuscript and addressing reviewer comments. CBe was the study librarian on the study. She cobuilt the search strategy with the graduate students and contributed to the draft and review of the methods of this manuscript. She also reviewed the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Dataset is available from corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Statistics Canada. Census of Canada. 2011. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm (Accessed 31 Aug 2014).

- 2. Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med 2014;44:1303–17. 10.1017/S0033291713001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Making the case for investing in mental health in canada. 2013.

- 5. Mcdonald KC, Bulloch AG, Duffy A, et al. Prevalence of Bipolar I and II Disorder in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:151–6. 10.1177/070674371506000310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kidd SA, Mckenzie KJ, Virdee G. Mental health reform at a systems level: widening the lens on recovery-oriented care. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:243–9. 10.1177/070674371405900503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. British Journal of Psychiatry 2013;202:s5–s10. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet 2012;379:1641–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, et al. Uses and abuses of recovery: implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014;13:12–20. 10.1002/wps.20084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McFarlane WR, Levin B, Travis L, et al. Clinical and Functional Outcomes After 2 Years in the Early Detection and Intervention for the Prevention of Psychosis Multisite Effectiveness Trial. Schizophrenia bulletin 2014. (published Online First: 30 Jul 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ellison ML, Klodnick VV, Bond GR, et al. Adapting Supported Employment for Emerging Adults with Serious Mental Health Conditions. The journal of behavioral health services & research 2014. (published Online First: Nov 2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, et al. Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: best available evidence and future directions. Med J Aust 2017;207:S5–S18. 10.5694/mja17.00694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bond GR, Drake RE. Making the case for IPS supported employment. Adm Policy Ment Health 2014;41:69–73. 10.1007/s10488-012-0444-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoffmann H, Jäckel D, Glauser S, et al. Long-term effectiveness of supported employment: 5-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:1183–90. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13070857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brimblecombe N, Knapp M, Murguia S, et al. The role of youth mental health services in the treatment of young people with serious mental illness: 2-year outcomes and economic implications. Early Interv Psychiatry 2017;11:393–400. 10.1111/eip.12261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM. Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis: an overview. World Psychiatry 2017;16:251–65. 10.1002/wps.20446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kozloff N, Stergiopoulos V, Adair CE, et al. The Unique Needs of Homeless Youths With Mental Illness: Baseline Findings From a Housing First Trial. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:1083–90. appips201500461 10.1176/appi.ps.201500461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2016;387:2383–401. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalinyak CM, Gary FA, Killion CM, et al. The Transition to Independence Process: Promoting Self-Efficacy in Transition-Aged Youths. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2016;54:49–53. 10.3928/02793695-20160119-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, O’Campo P, et al. Housing First: exploring participants’ early support needs. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:167 10.1186/1472-6963-14-167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016;387:2423–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 1993;16:11–23. 10.1037/h0095655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slade M. Routine outcome assessment in mental health services. Psychol Med 2002;32:1339–43. 10.1017/S0033291701004974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tse S, Tsoi EW, Hamilton B, et al. Uses of strength-based interventions for people with serious mental illness: A critical review. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2016;62:281–91. 10.1177/0020764015623970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, et al. The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2016;25:113–22. 10.1017/S2045796015001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bond GR, Drake RE, Campbell K. Effectiveness of individual placement and support supported employment for young adults. Early Interv Psychiatry 2016;10 10.1111/eip.12175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bassett J, Lloyd C, Bassett H. Work issues for young people with psychosis: Barriers to employment. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2001;64:66–72. 10.1177/030802260106400203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Latimer EA, Bond GR, Drake RE. Economic approaches to improving access to evidence-based and recovery-oriented services for people with severe mental illness. Can J Psychiatry 2011;56:523–9. 10.1177/070674371105600903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krueger JI, Vohs KD, Baumeister RF. Is the allure of self-esteem a mirage after all? Am Psychol 2008;63:64–5. discussion 65-6. doi 10.1037/0003-066X.63.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW. Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol 2008;95:695–708. 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellison ML, Danley KS, Bromberg C, et al. Longitudinal outcome of young adults who participated in a psychiatric vocational rehabilitation program. Psychiatr Rehabil J 1999;22:337–41. 10.1037/h0095218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guada JM, Conrad TL, Mares AS. The aftercare support program: An emerging group intervention for transition-aged youth. Soc Work Groups 2012;35:164–78. 10.1080/01609513.2011.604765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stone RA, Delman J, McKay CE, et al. Appealing features of vocational support services for hispanic and non-hispanic transition age youth and young adults with serious mental health conditions. J Behav Health Serv Res 2015;42:452–65. 10.1007/s11414-014-9402-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Waghorn G, Hielscher E. The availability of evidence-based practices in supported employment for Australians with severe and persistent mental illness. Aust Occup Ther J 2015;62:141–4. 10.1111/1440-1630.12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harvey SB, Henderson M, Lelliott P, et al. Mental health and employment: much work still to be done. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:201–3. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tindall RM, Simmons MB, Allott K, et al. Essential ingredients of engagement when working alongside people after their first episode of psychosis: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2018;12:784–95. 10.1111/eip.12566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. MacDonald K, Fainman-Adelman N, Anderson KK, et al. Pathways to mental health services for young people: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018;53:1005–38. 10.1007/s00127-018-1578-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Santesteban-Echarri O, Paino M, Rice S, et al. Predictors of functional recovery in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2017;58:59–75. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. OnTrackNY/Washington Heights Community Service, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. Silver award: providing recovery-oriented early intervention services to youths experiencing first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:e7–e8. 10.1176/appi.ps.681005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Henderson JL, Cheung A, Cleverley K, et al. Integrated collaborative care teams to enhance service delivery to youth with mental health and substance use challenges: protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014080 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burke-Miller J, Razzano LA, Grey DD, et al. Supported employment outcomes for transition age youth and young adults. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2012;35:171–9. 10.2975/35.3.2012.171.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dudley R, Nicholson M, Stott P, et al. Improving vocational outcomes of service users in an Early Intervention in Psychosis service. Early Interv Psychiatry 2014;8:98–102. 10.1111/eip.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baksheev GN, Allott K, Jackson HJ, et al. Predictors of vocational recovery among young people with first-episode psychosis: findings from a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2012;35:421–7. 10.1037/h0094574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ferguson KM. Using the Social Enterprise Intervention (SEI) and Individual Placement and Support (IPS) models to improve employment and clinical outcomes of homeless youth with mental illness. Soc Work Ment Health 2013;11:473–95. 10.1080/15332985.2013.764960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Killackey E, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD. Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. Br J Psychiatry 2008;193:114–20. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Porteous N, Waghorn G. Developing evidence-based supported employment services for young adults receiving public mental health services. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy 2009;56:34–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Knapp M, Patel A, Curran C, et al. Supported employment: cost-effectiveness across six European sites. World Psychiatry 2013;12:60–8. 10.1002/wps.20017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Arskey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schuring M, Mackenbach J, Voorham T, et al. The effect of re-employment on perceived health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:639–44. 10.1136/jech.2009.103838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hill ML, Banks PD, Handrich RR, et al. Benefit-cost analysis of supported competitive employment for persons with mental retardation. Res Dev Disabil 1987;8:71–89. 10.1016/0891-4222(87)90041-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shafer MS, Hill J, Seyfarth J, et al. Competitive employment and workers with mental retardation: analysis of employers’ perceptions and experiences. Am J Ment Retard 1987;92:304–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rusch FR, Hughes C. Supported employment: promoting employee independence. Ment Retard 1988;26:351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wehman P, Kreutzer J, West M, et al. Employment outcomes of persons following traumatic brain injury: pre-injury, post-injury, and supported employment. Brain Inj 1989;3:397–412. 10.3109/02699058909004563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wacker DP, Fromm-Steege L, Berg WK, et al. Supported employment as an intervention package: a preliminary analysis of functional variables. J Appl Behav Anal 1989;22:429–39. 10.1901/jaba.1989.22-429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. United Nations. Secretary-General’s Report to the General Assembly A/36/215, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 56. United Nations. Secretary-General’s Report to the General Assembly, A/40/256, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 57. United Nations. General Assembly Resolution, A/RES/50/81, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ferguson KM, Xie B, Glynn S. Adapting the Individual Placement and Support Model with Homeless Young Adults. Child Youth Care Forum 2012;41:277–94. 10.1007/s10566-011-9163-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rinaldi M, Mcneil K, Firn M, et al. What are the benefits of evidence-based supported employment for patients with first-episode psychosis? Psychiatr Bull 2004;28:281–4. 10.1192/pb.28.8.281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Waghorn G, Collister L, Killackey E, et al. Challenges to implementing evidence-based supported employment in Australia. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2007;27:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tapfumaneyi A, Johnson S, Joyce J, et al. Predictors of vocational activity over the first year in inner-city early intervention in psychosis services. Early Interv Psychiatry 2015;9:447–58. 10.1111/eip.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bond GR, Drake RE, Luciano A. Employment and educational outcomes in early intervention programmes for early psychosis: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2015;24:446–57. 10.1017/S2045796014000419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Henderson JL, Hawke LD, Chaim G, et al. Not in employment, education or training: Mental health, substance use, and disengagement in a multi-sectoral sample of service-seeking Canadian youth. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;75:138–45. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lindsay S. Discrimination and other barriers to employment for teens and young adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33(15-16):1340–50. 10.3109/09638288.2010.531372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Labonte R. Heart health inequalities in Canada: modules, theory and planning. Health Promot Int 1992;7:119–28. 10.1093/heapro/7.2.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Piat M, Sabetti J, Bloom D. The transformation of mental health services to a recovery-orientated system of care: Canadian decision maker perspectives. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2010;56:168–77. 10.1177/0020764008100801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vander Stoep A, Beresford SA, Weiss NS, et al. Community-based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorder. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:352–62. 10.1093/aje/152.4.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gilmer TP, Ojeda VD, Leich J, et al. Assessing needs for mental health and other services among transition-age youths, parents, and providers. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:338–42. 10.1176/appi.ps.201000545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Haber MG, Karpur A, Deschênes N, et al. Predicting improvement of transitioning young people in the partnerships for youth transition initiative: findings from a multisite demonstration. J Behav Health Serv Res 2008;35:488–513. 10.1007/s11414-008-9126-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lindsay S. Employment status and work characteristics among adolescents with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:843–54. 10.3109/09638288.2010.514018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Veldman K, Reijneveld SA, Ortiz JA, et al. Mental health trajectories from childhood to young adulthood affect the educational and employment status of young adults: results from the TRAILS study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:588–93. 10.1136/jech-2014-204421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Noel VA, Oulvey E, Drake RE, et al. Barriers to Employment for Transition-age Youth with Developmental and Psychiatric Disabilities. Adm Policy Ment Health 2017;44:354–8. 10.1007/s10488-016-0773-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Luciano A, Carpenter-Song EA. A qualitative study of career exploration among young adult men with psychosis and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Dual Diagn 2014;10:220–5. 10.1080/15504263.2014.962337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Luciano A, Bond GR, Drake RE. Does employment alter the course and outcome of schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses? A systematic review of longitudinal research. Schizophr Res 2014;159(2-3):312–21. 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nochajski SM, Schweitzer JA. Promoting school to work transition for students with emotional/behavioral disorders. Work 2014;48:413–22. 10.3233/WOR-131790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Meeting the needs of young people. IPPF Med Bull 1984;18:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ellison ML, Klodnick VV, Bond GR, et al. Adapting supported employment for emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. J Behav Health Serv Res 2015;42:206–22. 10.1007/s11414-014-9445-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Killackey E, Allott K, Cotton SM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of vocational intervention for young people with first-episode psychosis: method. Early Interv Psychiatry 2013;7:329–37. 10.1111/eip.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Killackey E, Waghorn G. The challenge of integrating employment services with public mental health services in Australia: progress at the first demonstration site. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2008;32:63–6. 10.2975/32.1.2008.63.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mueser KT, Cook JA. Why can’t we fund supported employment? Psychiatr Rehabil J 2016;39:85–9. 10.1037/prj0000203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Bond GR. Recent advances in supported employment for people with serious mental illness. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2016;29:196–201. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Cheungpasitporn W, Horne JM, Howarth CB. Adrenocortical carcinoma presenting as varicocele and renal vein thrombosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:337 10.1186/1752-1947-5-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rinaldi M, Perkins R, McNeil K, et al. The Individual Placement and Support approach to vocational rehabilitation for young people with first episode psychosis in the UK. J Ment Health 2010;19:483–91. 10.3109/09638230903531100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Brady WJ, Ferguson JD, Ullman EA, et al. Myocarditis: emergency department recognition and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2004;22:865–85. 10.1016/j.emc.2004.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tandon SD, Latimore AD, Clay E, et al. Depression outcomes associated with an intervention implemented in employment training programs for low-income adolescents and young adults. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:31–9. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. 2016. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html (accessed 6 Sep 2016).

- 87. Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Canada’s strategy for patient-oriented research - patient engagement framework. 2015.

- 88. Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA 2014;312:1513–4. 10.1001/jama.2014.11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Selby JV, Forsythe L, Sox HC. Stakeholder-driven comparative effectiveness research: An update from PCORI. JAMA 2015;314:2235–6. 10.1001/jama.2015.15139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Danley KS, Sciarappa K, MacDonald-Wilson K. Choose-get-keep: a psychiatric rehabilitation approach to supported employment. New Dir Ment Health Serv 1992;53:87–96. 10.1002/yd.23319925310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.