Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to validate the performance of the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) in a Chinese emergency department and to determine the best cut-off value for in-hospital mortality prediction.

Design

A prospective, single-centred observational cohort study.

Setting

This study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in South China.

Participants

A total of 383 patients aged 18 years or older who presented to the emergency department from 17 May 2017 through 27 September 2017, triaged as category 1, 2 or 3, were enrolled.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of in-hospital mortality and admission to the intensive care unit. The secondary outcome was using MEWS to predict hospitalised and discharged patients.

Results

A total of 383 patients were included in this study. In-hospital mortality was 13.6% (52/383), and transfer to the intensive care unit was 21.7% (83/383). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of MEWS for in-hospital mortality prediction was 0.83 (95% CI 0.786 to 0.881). When predicting in-hospital mortality with the cut-off point defined as 3.5, 158 patients had MEWS >3.5, with a specificity of 66%, a sensitivity of 87%, an accuracy of 69%, a positive predictive value of 28% and a negative predictive value of 97%, respectively.

Conclusion

Our findings support the use of MEWS for in-hospital mortality prediction in patients who were triaged category 1, 2 or 3 in a Chinese emergency department. The cut-off value for in-hospital mortality prediction defined in this study was different from that seen in many other studies.

Keywords: ("modified early warning score") or "mews", ("emergency") and "triage", emergency department

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This prospective observational study was carried out according to workflow, which is the most cost-effective option and reduces difficulty in data collection.

This study used a prospective study design and provided a new cut-off point for the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) using the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to increase sensitivity in predicting in-hospital mortality.

This study evaluated the MEWS only once, on patient admission, which means that dynamic changes in the score could not be observed during patient hospitalisation.

This prospective cohort study recruited participants at a single medical centre, which could limit the generalisability of the study findings.

Introduction

Different kinds of triage systems have been developed worldwide to assess the illness severity of patients presenting to emergency departments (EDs) who are assigned treatment priorities.1 2 In China, there is a lack of a unified triage standard to manage patients when they present to the ED.3 The triage standard used in hospitals in Shenzhen is a new four-level Chinese emergency triage criteria, published by the Public Hospital Administration of Shenzhen Municipality in August 2013.3 It categorises patients as near death (level 1), critically ill (level 2), acute (level 3) and not acute (level 4), requiring treatment immediately, in 10 min, in 30 min and in 4 hours, respectively. This is mainly decided according to patients’ presenting complaints and questions about potentially aggravating factors. According to acuity, level 1, level 2 and level 3 are urgent patients with a higher risk of serious adverse events, such as hospital admission and mortality, compared with level 4, which describes non-urgent patients.4 5

Therefore, an excellent scoring system is urgently required for mortality predictions in patients admitted to the ED. Today, there are a number of scoring systems designed to predict the chances of hospitalisation, intensive care unit (ICU) admission or in-hospital mortality in ED patients.6 7 The VitalPac Early Warning Score, Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), Rapid Emergency Medicine Score, Emergency Department Sepsis Score and Rapid Acute Physiology Score are the most commonly employed systems for bedside evaluation.8–12

MEWS was introduced in 2001 by Subbe and colleagues,13 who modified it from the Early Warning Score (EWS). The MEWS is a simple physiological scoring system which includes five physiological parameters—systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, temperature and level of consciousness—that can easily be collected at the moment of presentation. The MEWS is widely used in wards, ICU and EDs to detect the clinical deterioration of patients or to predict clinical outcomes.6 7 13

A large number of studies have reported that MEWS is an effective tool for in-hospital mortality prediction.14–17 However, there have also been studies conducted on different populations or in different areas reporting that MEWS is not an adequate scoring system for predicting in-hospital mortality.18 19 Moreover, the MEWS cut-off value (for in-hospital mortality prediction reported in studies) varies.9 10 15 20–22 A study conducted on 518 patients in ICU indicated that patients with MEWS ≥6 had significantly higher mortality than those with MEWS <6.22 However, another study, which examined the performance of MEWS in assessing non-traumatic critical patients in an ED, showed the MEWS cut-off value was 3.15 Therefore, this study hypothesises that MEWS performance and cut-off value may differ according to the specific population.

The MEWS is also used to evaluate patient conditions in Chinese EDs, including focusing on the relationship between factors and clinical outcomes, using prehospital MEWS to identify non-trauma patients requiring life-saving intervention and risk stratification of patients before interfacility transport.23–25 However, information on MEWS validation is limited to in-hospital mortality predictions in patients triaged as level 1, 2 or 3 in Chinese EDs. Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate MEWS performance in predicting in-hospital mortality of the population in a Chinese emergency treatment room and to find the best cut-off value.

Methods

Study design

A prospective, single-centred observational cohort study was conducted in the ED of a tertiary hospital in Shenzhen, China to evaluate the ability of the MEWS to predict in-hospital mortality in patients presenting to the emergency treatment room who were categorised level 1, 2 or 3.

Study population

The study was carried out at a tertiary hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University, which saw 173 000 ED presentations in 2017. Of the 173 000 ED presentations, approximately 6600 patients were admitted to the emergency treatment room. Data of patients presenting to the emergency treatment room between 17 May 2017 and 27 September 2017 were collected. Patients aged 18 years or older triaged as categories 1, 2 and 3 were included in the study. Patients who had died prior to arrival in the ED and patients who needed ward admission, ICU admission or rescue according to the doctor’s judgement, or who ignored the doctor’s advice and left the hospital due to a variety of reasons, were excluded from the study. Patients with insufficient information were also excluded.

Sample size calculation

This study calculated the sample size using G*Power V.3.1.9.2 (http://www.softpedia.com/get/Science-CAD/G-Power.shtml). The estimated sample size was 319, with an accuracy index of 0.95 and a marginal error of 0.05 with 95% confidence level and 80% power.

Participant involvement and data collection

Patients who presented to our ED were evaluated and triaged by the triage nurse, who had more than 5 years of experience. Patients were triaged to near death (level 1), critically ill (level 2), acute (level 3) and not acute (level 4). This is decided according to the triage guidelines and the judgement of the triage nurse. According to acuity, patients triaged to levels 1 and 2 were sent to the emergency treatment room; patients triaged to level 3 were given priority in the consulting room or sent to the emergency treatment room if the triage nurse judged the patient’s condition to be serious; and patients triaged to level 4 were sent to wait outside the consulting room.

Physiological parameters were measured by nurses and researchers at the time of admittance to the emergency treatment room. Respiratory rate was counted manually for more than a full minute; heart rate and blood pressure were measured using an automatic electronic sphygmomanometer (HBP-9020) or multifunctional ECG monitor (Philips Jin Kewei, G30). Body temperature was measured using an infrared ear thermometer (PRO 4000). The level of consciousness was recorded as the best response to the AVPU score (A for alert, V for reacting to vocal stimulus, P for reacting to pain and U for unresponsive). Patient information was recorded using a questionnaire designed by the researchers. The following information was included: age, gender, nationality, educational background, mode of transportation to hospital, disease type, main diagnosis, body temperature, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, peripheral oxygen saturation, AVPU score, triage level, MEWS score (online supplementary appendix 1) and mortality.

bmjopen-2018-024120supp001.pdf (252.4KB, pdf)

The patients were followed up by the researcher until discharge, death or for a maximum of 90 days. The researchers calculated the MEWS using patients’ five recorded physiological parameters. In-hospital mortality was the main outcome. The predictive accuracy of the MEWS was evaluated by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were analysed to indicate the predictive power of the scoring system. The patients were divided into two groups: MEWS <4 and MEWS ≥4. The intergroup differences in the baseline characteristic physiological parameters and the scores between the two groups were also evaluated.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of in-hospital mortality and admission to the ICU. The secondary outcome of this study was using MEWS to predict admission to the general ward unit or discharge from hospital.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were tabulated for the overall sample. Mean and SD were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for all other categorical variables. Data distribution of each variable between the MEWS <4 and the MEWS ≥4 groups was compared. In addition, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was measured to evaluate the predictive ability of the MEWS. Finally, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV and NPV were also analysed. Regression analysis was used to address confounding variables of age and gender. P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. EpiData V.3.1 was used for data entry, and then exported to tab-delimited text files. All analyses were performed using R (http://www.R-project.org) and EmpowerStats (www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Boston, Massachusetts) software.

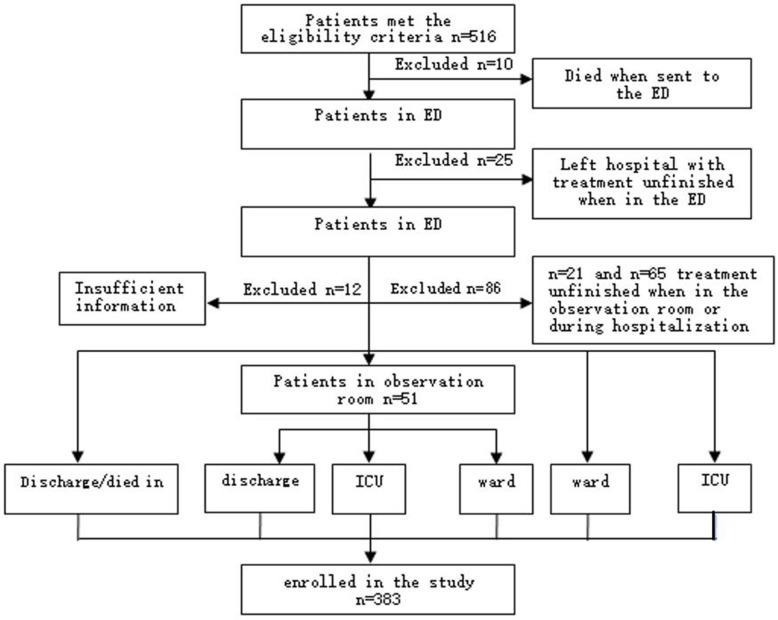

Results

A total of 516 patients met the eligibility criteria, with 133 patients excluded. Among the patients who were excluded from the study, 10 had already died when they were sent to the ED, while 46 patients in the ED ignored the advice of doctors and left the hospital due to a variety of reasons. Another 65 patients left the hospital after being admitted to the ward or ICU. Twelve patients were excluded due to insufficient information (figure 1). Ultimately, 383 patients were enrolled in the study. Of this total, 255 (66.6%) patients were male; the mean age of all patients was 59.6±18.3 years, and the ethnicity of the majority of patients was Han Chinese (98.2%). Among the 383 patients, 52.5% and 21.7% were admitted to the ward and ICU from the ED, respectively. Nervous system, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases were the three most common disease types seen in these patients, consisting of more than half of the population. In the baseline characteristics between the MEWS <4 and MEWS ≥4 groups, a number of baseline characteristics showed significant differences, with p<0.05. Detailed patient baseline characteristics are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study procedure. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics between the MEWS <4 and MEWS ≥4 groups

| Characteristics | All, n (%) | MEWS <4 | MEWS ≥4 | P value |

| n=383 | n=225 | n=158 | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 59.6 (18.3) | 57.9 (16.9) | 62.1 (19.9) | 0.008 |

| Gender | 0.43 | |||

| Male | 255 (66.6) | 159 (70.7) | 96 (60.8) | |

| Female | 128 (33.4) | 66 (29.3) | 62 (39.2) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.525 | |||

| Han | 376 (98.2) | 222 (98.7) | 154 (97.5) | |

| Hui | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Manchu | 6 (1.6) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Means of arrival | 0.009 | |||

| Walking | 123 (32.1) | 86 (38.2) | 37 (23.4) | |

| Wheelchair | 8 (2.1) | 4 (1.8) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Ambulance | 252 (66.8) | 135 (60.0) | 117 (74.1) | |

| Triage | <0.001 | |||

| Discharged from ED | 38 (9.9) | 31 (13.8) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Observation room | 51 (13.3) | 39 (17.3) | 12 (7.6) | |

| Ward admission | 201 (52.5) | 126 (56.0) | 75 (47.5) | |

| ICU admission | 83 (21.7) | 28 (12.4) | 55 (34.8) | |

| Died in ED | 10 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 9 (5.7) | |

| Disease types | 0.003 | |||

| Respiratory system | 54 (14.1) | 19 (8.4) | 35 (22.2) | |

| Digestive system | 36 (9.4) | 23 (10.2) | 13 (8.2) | |

| Cardiovascular system | 82 (21.4) | 50 (22.2) | 32 (20.3) | |

| Nervous system | 99 (25.8) | 69 (30.7) | 30 (19.0) | |

| Haematological system | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Endocrinological, metabolism | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Urinary system | 15 (3.9) | 7 (3.1) | 8 (5.1) | |

| Trauma | 28 (7.3) | 17 (7.56) | 11 (7.0) | |

| Others | 63 (16.5) | 34 (15.1) | 29 (18.4) |

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

The patients were divided into two groups: MEWS ≥4 and MEWS <4. Physiological parameters include body temperature, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, percutaneous oxygen saturation and mental status, which were different between the two groups, and the difference was statistically significant. However, between the two groups, there were no differences in terms of blood sugar and length of stay. In addition, a total of 277 critically ill patients were triaged as level 1 and level 2, requiring treatment within 10 min. There were more critically ill patients in the MEWS ≥4 group than in the MEWS <4 group (150/158 vs 127/225, p<0.001). The proportion of in-hospital mortality was 13.6% (52/383), with most of these patients in the MEWS ≥4 group (7/52 vs 45/52, p<0.001). Detailed physiological parameters of the two groups are outlined in table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical parameters between patients with MEWS <4 and MEWS ≥4

| Parameters | All, n (%) | MEWS <4 | MEWS ≥4 | P value |

| n=383 | n=225 | n=158 | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 59.6 (18.3) | 57.9 (16.9) | 62.1 (19.9) | 0.008 |

| Gender | 0.430 | |||

| Male | 255 (66.6) | 159 (70.7) | 96 (60.8) | |

| Female | 128 (33.4) | 66 (29.3) | 62 (39.2) | |

| Physiology, mean (SD) | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.2 (1.0) | 36.9 (0.6) | 37.6 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 136.6 (33.6) | 140.9 (29.6) | 130.3 (37.9) | 0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 80.3 (21.1) | 82.8 (18.4) | 76.80 (24.0) | 0.002 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 95.2 (30.8) | 80.7 (15.4) | 116.0 (35.0) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (bpm) | 23.1 (6.3) | 20.7 (3.0) | 26.6 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| SPO2 median (IQR) | 99.0 (4) | 99 (2) | 98 (5) | <0.001 |

| BS median (IQR) | 8.0 (3.4) | 8.0 (3.2) | 8.2 (3.6) | 0.461 |

| LOS median (IQR) | 12 (11) | 11 (9) | 14 (14) | 0.068 |

| Mental status | <0.001 | |||

| Alert | 280 (73.1) | 193 (85.8) | 87 (55.1) | |

| Reacting to voice | 39 (10.1) | 21 (9.3) | 18 (11.4) | |

| Reacting to pain | 32 (8.4) | 10 (4.4) | 22 (13.9) | |

| Unresponsive | 32 (8.4) | 1 (0.4) | 31 (19.6) | |

| Triage level | <0.001 | |||

| Level 1 | 69 (18.0) | 8 (3.6) | 61 (38.6) | |

| Level 2 | 208 (54.3) | 119 (52.9) | 89 (56.3) | |

| Level 3 | 106 (27.7) | 98 (43.6) | 80 (5.1) | |

| Survivors | 331 (86.4) | 218 (96.9) | 113 (71.5) | <0.001 |

| Non-survivors | 52 (13.6) | 7 (3.1) | 45 (28.5) | <0.001 |

bpm, beats or breaths per minute; BS, blood sugar; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LOS, length of stay; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SPO2, percutaneous oxygen saturation.

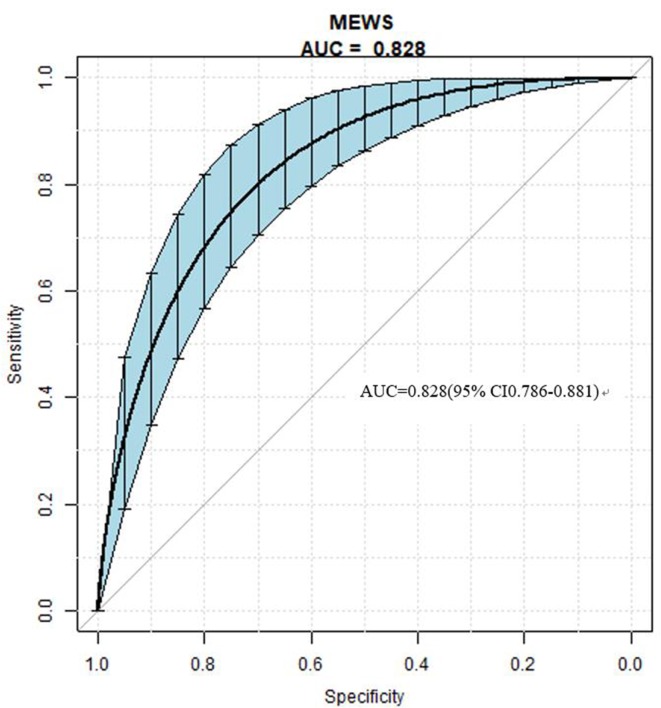

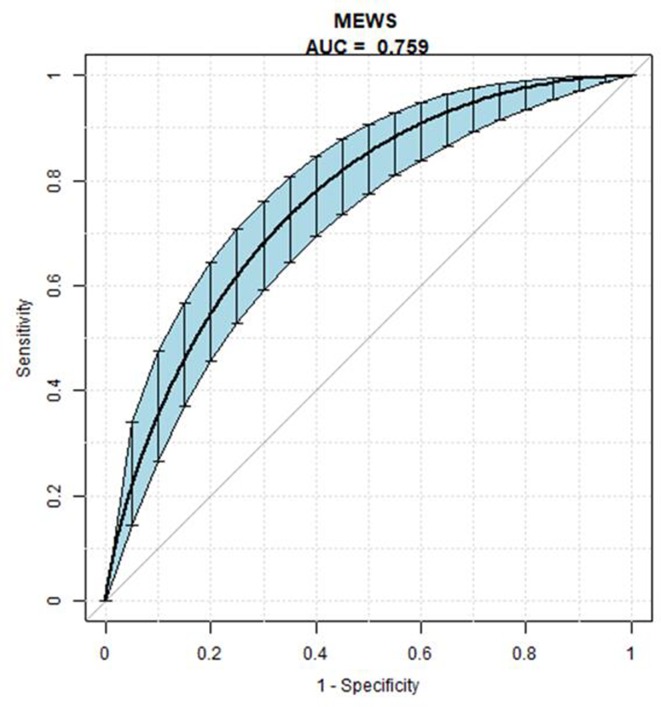

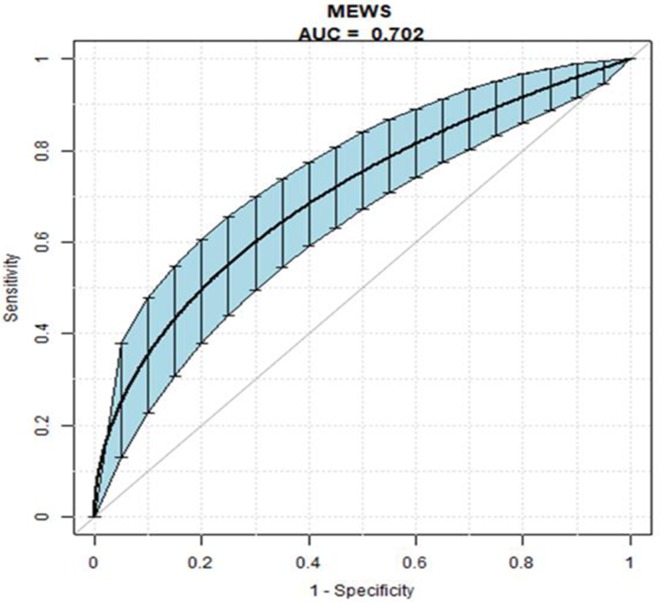

The MEWS in-hospital mortality predictive ability is shown by AUC, at 0.83 (95% CI 0.786 to 0.881) (figure 2). Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between MEWS and the primary and secondary outcome measures. As seen in table 3, the MEWS was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.65, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.89, p<0.001), admission to ICU (OR, 1.54, 95% CI 1.39 to 1.72, p<0.001), and predicting admission to a general ward unit or discharge from hospital (OR, 1.55, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.89, p<0.001) (table 3). The MEWS in-hospital mortality, predictive ability of admission to ICU and predictive ability of admission to a general ward unit or discharge from hospital are shown in figure 2–4, respectively.

Figure 2.

The AUC value of MEWS for predicting in-hospital mortality. Blue shading shows the bootstrap estimated 95% CI with AUC. AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

Table 3.

Association of MEWS with in-hospital mortality, admission to ICU and predicting admission to general ward unit or discharge from hospital

| MEWS | Model 1, OR (95% CI) P value |

Model 2, OR (95% CI) P value |

| In-hospital mortality | 1.66 (1.45 to 1.90) <0.001 |

1.65 (1.44 to 1.89) <0.001 |

| Admission to ICU | 1.52 (1.37 to 1.69) <0.001 |

1.54 (1.39 to 1.72) <0.001 |

| Predicting admission to general ward unit or discharge from hospital | 1.54 (1.27 to 1.86) <0.001 |

1.55 (1.28 to 1.89) <0.001 |

Model 1, original model; model 2 with adjustment for age and gender. Presented as OR with 95% CI (MEWS ≥4 and MEWS <4 as reference).

ICU, intensive care unit; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

Figure 3.

The AUC value of MEWS for predicting admission to intensive care unit. Blue shading shows the bootstrap estimated 95% CI with AUC. AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

Figure 4.

The AUC value of MEWS for predicting admission to general ward unit or discharge from hospital. Blue shading shows the bootstrap estimated 95% CI with AUC. AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

Discussion

In this observational cohort study, the MEWS showed good performance for in-hospital mortality prediction, with AUC values at 0.83. The higher the score, the higher the ratio of in-hospital mortality, indicating that MEWS was significantly correlated with patient mortality. In patients with MEWS ≥4, compared with MEWS <4, a number of variables, such as age, triage level, vital signs, means of arrival and disease type, are influencing factors of death in ED patients. The study demonstrated that MEWS is an effective tool for in-hospital mortality prediction for ED patients triaged to levels 1, 2 and 3.

MEWS is a widely used scoring system in many countries, but differences between these studies, including study setting, population and disease type, have led to differences in the predictive ability of the MEWS. The AUC, specificity and sensitivity were the most common indexes reported in studies on MEWS performance.17 20 26 27 A large proportion of studies have reported that MEWS is an effective tool for mortality prediction, with AUC ranging from approximately 0.70 to 0.89 for the most frequently used threshold (MEWS=5), and specificity and sensitivity ranging from 0.67 to 0.72, and from 0.65 to 0.71, respectively.9 17 20 26 However, less information was provided on the accuracy, PPV and NPV of the score. In a single-centre, observational cohort study conducted at an urban tertiary care medical centre in Chicago, adult patients who were suspected of contracting an infection in a hospital ward or ED were included.20 Discrimination for in-hospital mortality was moderate, with MEWS AUC of 0.73 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.74).

Furthermore, there are also studies demonstrating that MEWS is not an efficient system for mortality prediction, with an approximate AUC of less than 0.6, with study populations that included patients with sepsis admitted to medical wards, surgical patients presenting to EDs and adults admitted to medical wards, respectively.9 17 22 This study showed that disease and population differences seem to strongly determine MEWS performance. However, MEWS performance in ED patients who were triaged as level 1, 2 or 3 had previously not been validated. Our study found that mortality prediction for the MEWS is good (AUC, 0.83, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.88).

When combined with sensitivity and specificity, the maximum was defined as the best threshold. In this study, in order to increase the proportion of in-hospital mortality prediction and reduce missed diagnoses, sensitivity is more important than specificity. When the threshold was 4, the specificity, accuracy and NPV improved at the cost of sensitivity and PPV, and the number of deaths due to missed diagnosis increased from 6 to 16. Hence, this study defined the MEWS cut-off point as 4, which was different from a previous prospective study, whose MEWS cut-off point was defined as 3.15 However, the MEWS cut-off point defined as 3 in this study was different from that of many other studies, whose MEWS cut-off point was defined as 5 or higher.10 20–22 For the baseline characteristics of patients in this study, respiratory system diseases, digestive system diseases, circulatory system diseases and nervous system diseases were found in 70.7% of the population and 67.3% of non-survivors, with the median (IQR) MEWS at 3 (3). Different kinds of diseases and populations may have contributed to the difference. In general, our study provides evidence that the MEWS is an efficient system for in-hospital mortality prediction in an ED.

Limitations and implications for future research

There are several limitations in our study. First, this was a single-centre, observational cohort study at a tertiary hospital in Shenzhen. Patient outcomes may have been affected by the level of care provided by the hospital, and may therefore have also affected the performance of the MEWS for in-hospital mortality prediction. Second, the population included in this study was selected according to triage criteria that were only published in Shenzhen. Therefore, our study results may not be generalisable to other settings. Third, we evaluated the MEWS only once, on patient admission. Dynamic changes in the score could not be observed during patient hospitalisation. Hence, we could not exclude the possibility that re-evaluation of this clinical score during hospitalisation may have improved or reduced the MEWS performance in this setting. In future, a multicentre study should be conducted to reduce the effect of the sample size not being representative. In addition, due to the varied performance of MEWS in other studies, research on specific diseases is also required in order for the use of MEWS to be more accurate. While the actual number of enrolled subjects was 383 (higher than the required sample size of 319), we excluded 133 patients in the analysis due to missing data, resulting in potential selection bias. Thus, future research should implement strategies to minimise missing data in patient report forms.

Conclusion

This study found that MEWS was an accurate score for predicting in-hospital mortality and admission to ICU in a Chinese ED. Future multicentric prospective cohort studies are needed to validate the study findings. As patients with MEWS equal to or higher than 4 had higher rates of in-hospital mortality and ICU admission, calculating MEWS may be an important indicator for closely monitoring patients, making an immediate request to contact the doctor in charge and establishing a rapid response intervention team. In this hospital, the ED triage system has already added MEWS as one of the vital parameter monitors and designed an algorithm in the triage system that can automatically calculate MEWS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Xinglin Chen for her excellent assistance with the statistical analyses. We also thank all patients for participating in this study.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributors: Study design: XX, WH and QL. Data acquisition: WH. Data analysis and interpretation: WH, LP, LW, JZ, YW and YZ. Project administration: XX and WT. Manuscript first draft: XX and WH. Statistical analysis: WH. Manuscript revision: WT and YZ.

Funding: This work was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Guangdong Province, China (grant number 2014A020212574).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Second People’s Hospital of Shenzhen (no 20141201005).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We are glad to share data collected in this study upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Krey J. Triage in emergency departments. Comparative evaluation of 4 international triage systems. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2016;111:124–33. 10.1007/s00063-015-0069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chang W, Liu HE, Goopy S, et al. . Using the five-level taiwan triage and acuity scale computerized system: factors in decision making by emergency department triage nurses. Clin Nurs Res 2017;26:651–66. 10.1177/1054773816636360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peng L, Hammad K. Current status of emergency department triage in mainland China: a narrative review of the literature. Nurs Health Sci 2015;17:148–58. 10.1111/nhs.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muncicipality PHAoS. The hospital emergency triage guidelines (Trial). 2013.

- 5. Yuksen C, Sawatmongkornkul S, Suttabuth S, et al. . Emergency severity index compared with 4-level triage at the emergency department of Ramathibodi University Hospital. Asian Biomedicine 2016;10:155–61. 10.5372/1905-7415.1002.477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zachariasse JM, Seiger N, Rood PP, et al. . Validity of the manchester triage system in emergency care: a prospective observational study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170811 10.1371/journal.pone.0170811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nannan Panday RS, Minderhoud TC, Alam N, et al. . Prognostic value of early warning scores in the emergency department (ED) and acute medical unit (AMU): A narrative review. Eur J Intern Med 2017;45:20–31. 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mapp ID, Davis LL, Krowchuk H. Prevention of unplanned intensive care unit admissions and hospital mortality by early warning systems. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2013;32:300–9. 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dundar ZD, Ergin M, Karamercan MA, et al. . Modified early warning score and vitalpac early warning score in geriatric patients admitted to emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 2016;23:406–12. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bulut M, Cebicci H, Sigirli D, et al. . The comparison of modified early warning score with rapid emergency medicine score: a prospective multicentre observational cohort study on medical and surgical patients presenting to emergency department. Emerg Med J 2014;31:476–81. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Galen LS, Dijkstra CC, Ludikhuize J, et al. . A protocolised once a day modified early warning score (MEWS) measurement is an appropriate screening tool for major adverse events in a general hospital population. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160811 10.1371/journal.pone.0160811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hung SK, Ng CJ, Kuo CF, et al. . Comparison of the mortality in emergency department sepsis score, modified early warning score, rapid emergency medicine score and rapid acute physiology score for predicting the outcomes of adult splenic abscess patients in the emergency department. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187495 10.1371/journal.pone.0187495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, et al. . Validation of a modified early warning score in medical admissions. QJM 2001;94:521–6. 10.1093/qjmed/94.10.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Winslow C, et al. . Differences in vital signs between elderly and nonelderly patients prior to ward cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med 2015;43:816–22. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Köksal Ö, Torun G, Ahun E, et al. . The comparison of modified early warning score and Glasgow coma scale-age-systolic blood pressure scores in the assessment of nontraumatic critical patients in Emergency Department. Niger J Clin Pract 2016;19:761–5. 10.4103/1119-3077.178944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Delgado-Hurtado JJ, Berger A, Bansal AB. Emergency department modified early warning score association with admission, admission disposition, mortality, and length of stay. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2016;6:31456 10.3402/jchimp.v6.31456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Winslow C, et al. . Multicenter development and validation of a risk stratification tool for ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:649–55. 10.1164/rccm.201406-1022OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tirotta D, Gambacorta M, La Regina M, et al. . Evaluation of the threshold value for the modified early warning score (MEWS) in medical septic patients: a secondary analysis of an Italian multicentric prospective cohort (SNOOPII study). QJM 2017;110:hcw229–373. 10.1093/qjmed/hcw229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho leO, Li H, Shahidah N, et al. . Poor performance of the modified early warning score for predicting mortality in critically ill patients presenting to an emergency department. World J Emerg Med 2013;4:273–8. 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, et al. . Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:906–11. 10.1164/rccm.201604-0854OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kruisselbrink R, Kwizera A, Crowther M, et al. . Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) identifies critical illness among ward patients in a resource restricted setting in Kampala, Uganda: a prospective observational study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151408 10.1371/journal.pone.0151408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reini K, Fredrikson M, Oscarsson A. The prognostic value of the modified early warning score in critically ill patients: a prospective, observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2012;29:152–7. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835032d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gu M, Fu Y, Li C, et al. . [The value of modified early warning score in predicting early mortality of critically ill patients admitted to emergency department]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2015;27:687–90. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leung SC, Leung LP, Fan KL, et al. . Can prehospital modified early warning score identify non-trauma patients requiring life-saving intervention in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas 2016;28:84–9. 10.1111/1742-6723.12501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee LL, Yeung KL, Lo WY, Wy L, et al. . Evaluation of a simplified therapeutic intervention scoring system (TISS-28) and the modified early warning score (MEWS) in predicting physiological deterioration during inter-facility transport. Resuscitation 2008;76:47–51. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eick C, Rizas KD, Meyer-Zürn CS, Grogabada P, et al. . Autonomic nervous system activity as risk predictor in the medical emergency department: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1079–86. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wheeler I, Price C, Sitch A, et al. . Early warning scores generated in developed healthcare settings are not sufficient at predicting early mortality in Blantyre, Malawi: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e59830 10.1371/journal.pone.0059830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024120supp001.pdf (252.4KB, pdf)