Abstract

Objective

To translate an informed shared decision-making programme (ISDM-P) for patients with type 2 diabetes from a specialised diabetes centre to the primary care setting.

Design

Patient-blinded, two-arm multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial of 6 months follow-up; concealed randomisation of practices after patient recruitment and acquisition of baseline data.

Setting

22 general practices providing care according to the German Disease Management Programme (DMP) for type 2 diabetes.

Participants

279 of 363 eligible patients without myocardial infarction or stroke.

Interventions

The ISDM-P comprises a patient decision aid, a corresponding group teaching session provided by medical assistants and a structured patient–physician encounter.

Control group received standard DMP care.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary endpoint was patient adherence to antihypertensive or statin drug therapy by comparing prescriptions and patient-reported uptake after 6 months. Secondary endpoints included informed choice, risk knowledge (score 0–11 from 11 questions) and prioritised treatment goals of patients and doctors.

Results

ISDM-P: 11 practices with 151 patients; standard care: 11 practices with 128 patients; attrition rate: 3.9%. There was no difference between groups regarding the primary endpoint. Mean drug adherence rates were high for both groups (80% for antihypertensive and 91% for statin treatment). More ISDM-P patients made informed choices regarding statin intake, 34% vs 3%, OR 16.6 (95% CI 4.4 to 63.0), blood pressure control, 39% vs 3%, OR 22.2 (95% CI 5.3 to 93.3) and glycated haemoglobin, 43% vs 3%, OR 26.0 (95% CI 6.5 to 104.8). ISDM-P patients achieved higher levels of risk knowledge, with a mean score of 6.96 vs 2.86, difference 4.06 (95% CI 2.96 to 5.17). In the ISDM-P group, agreement on prioritised treatment goals between patients and doctors was higher, with 88.5% vs 57%.

Conclusions

The ISDM-P was successfully implemented in general practices. Adherence to medication was very high making improvements hardly detectable.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN77300204; Results.

Keywords: primary care; diabetes mellitus, Type 2; decision support techniques; patient education as topic; health educators; health knowledge, attitudes, practice

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) followed the UK MRC framework for complex interventions and is the final step of the development and evaluation of an informed shared decision-making programme (ISDM-P) for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Efficacy of the ISDM-P was demonstrated in a former RCT under high-fidelity conditions in a diabetes centre. In this cluster RCT, the ISDM-P was integrated into routine care by addressing implementation barriers.

The cluster RCT was meticulously designed and conducted with a low drop-out rate; practices were only randomised after completion of patient recruitment and acquisition of baseline data.

It was planned to keep the patients blinded, but it was impossible to keep the healthcare providers (practices) blinded.

Since there is no gold standard to assess SDM in routine care, the patient-held sheet for personal treatment goals might be used as a surrogate indicator for SDM in diabetes care.

Introduction

Diabetes guidelines explicitly recommend shared decision-making (SDM) to help patients and physicians to make informed choices and to select the treatment that best fits individual patient needs, values and preferences.1 2 Patients increasingly want to participate in making decisions about their health, and they have the right to be involved.3 However, SDM is not yet implemented in diabetes care,4 and a number of barriers have been identified that are hindering this.5 While many clinicians believe that they already practise SDM, they in fact do not involve patients in treatment decision-making.5 6 Physicians are used to deciding what they consider best for their patients. Even if healthcare professionals are aware of such misconceptions about SDM, organisational structures (and mainly time constraints) are often perceived as barriers for patient involvement. Another challenge is the generally poor science literacy among health professionals and patients, and a lack of competencies for communicating and understanding risk information.7–9 Finally, there is a paucity of evidence-based patient information material such as decision aids or drug facts boxes, which display probabilities of benefits and harms of options and are the basis for informed decision-making.10 11 There are only a few projects on decision aids and SDM in diabetes care; these address different treatment regimens,12 statin treatment,13–15 oral antidiabetic agents,16 17 starting insulin injections18 or prevention of macrovascular and microvascular complications.19 Results about efficacy or implementation are ambiguous.

We have developed an informed SDM programme (ISDM-P) for patients with type 2 diabetes that targets implementation barriers.20 21 The ISDM-P comprises an evidence-based patient decision aid, a corresponding teaching session provided by specially trained medical assistants (MAs) and a structured patient–physician encounter. MAs and doctors are trained to provide risk information and to conduct consultations based on SDM principles. The ISDM-P is designed to be easily integrated in the structured treatment and teaching programme22–25 used in the German Disease Management Programme (DMP).26 We have compared the ISDM-P to a structurally equivalent control intervention in a proof-of-concept randomised controlled trial (RCT) at a single diabetes centre.21 About half of the ISDM-P patients, but none of the patients in the usual care group, attained adequate risk knowledge to make informed decisions. Nonetheless, patients’ treatment preferences were not adequately considered by physicians in decision-making. Although physicians expressed a positive attitude towards SDM, they had not been specifically trained in SDM. Therefore, we developed additional programme components to facilitate SDM-based patient–physician consultations.27

In the present study, we investigated whether the results of the proof-of-concept RCT21 could be repeated under routine care conditions for patients with type 2 diabetes. The aim was to translate the optimised ISDM-P to the primary healthcare setting.

Methods

Study design

The study was a two-arm, multicentre cluster RCT with 6 months follow-up. According to international standards for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, we additionally focused on implementation conditions and process parameters.28–31 A detailed protocol has been published.27

Patient involvement

In order to address patient and public involvement, patients participated in the development of the intervention material. We did not involve patients in the design of this study. After publication of the study, we will write a plain language summary and design a leaflet for distribution to patient groups. It will also be available on the project website (www.diabetes-und-herzinfarkt.de).

Context and setting

In Germany, care for patients with type 2 diabetes is usually provided by family physicians at the primary healthcare level. The study took place in 21 primary care practices in East Germany (Free State of Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt) and one in the city of Hamburg. Practices were included if they provided structured teaching and treatment according to the German DMP for type 2 diabetes.32 33 Patient education was provided by diabetes educators or MAs with special training in diabetes education.34 A more detailed description is given in the protocol.27

Participants

Patients between 40 and 69 years who had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, had glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels of <9% and had previously participated in structured DMP teaching sessions were included. Exclusion criteria were a history of ischaemic heart disease (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) I20-I25) or stroke (ICD I63), proliferative retinopathy, chronic kidney disease stage 3 or higher or care by a legal guardian. All participants gave informed written consent.

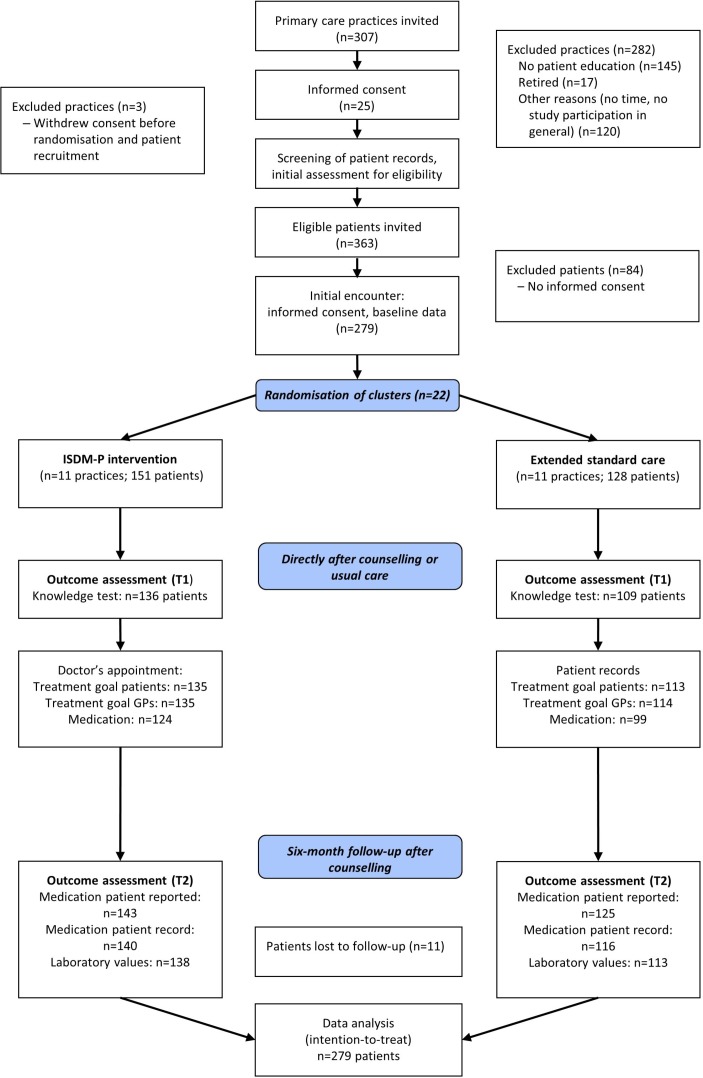

Study recruitment

A total of 307 general practices of the study regions were informed about the project by mail (figure 1). Two weeks later, the practices were called and asked whether they were interested in participating in the study. Supported by the research associate, MAs and general practitioners (GPs) of each practice screened the patient records for eligibility. Patients of the included practices were then informed about the study by a letter and invited to participate during the next consultation with their GPs. After patients who were willing to participate had given informed consent, baseline data were retrieved directly from patients and supplemented by standard data extracted from the electronic patient records.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. GP, general practitioner; ISDM-P, informed shared decision-making programme; T1, directly after counselling or usual care; T2, 6-month follow-up.

Concealed external randomisation of practices (cluster) started only after conclusion of patient recruitment and collection of baseline data at the study centre.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Association of the Federal State of Thuringia in April 2014. It was submitted to registration in February 2015. The study protocol was published in March 2015.27 In order to avoid undue delays in recruitment of study participants, we started enrolment of family practices and patients in December 2014. During that time, we checked if prescription rates of statins and antihypertensive agents were comparable between our former proof-of-concept study and the primary care setting to make sure that our sample size calculation is adequate. Practices were randomised only after trial registration and after publication of the study protocol. In fact, we did not change our original sample size calculation. We think that our approach did not bias our study results. The last practice was enrolled in August 2015, and the last patient, in April 2016. The overall trial end date should have been July 2016, but as some practices required more time for patient recruitment, data collection was completed in March 2017. Please refer to online supplementary data S1 study procedure and registration, for in depth detail of this.

bmjopen-2018-024004supp001.pdf (153.3KB, pdf)

Intervention

The ISDM-P comprises a number of interrelated components (online supplementary data S2).27 Those components that had already been tested in the proof-of-concept RCT21 were: (1) an evidence-based patient decision aid about the primary prevention of myocardial infarction and other diabetes-related complications20; (2) a structured group teaching session provided by MAs and (3) a provider training for MAs. The additional components developed for implementation in routine care were: (4) a patient-held documentation sheet with patient-defined treatment goals, to be shared and discussed by the patient with the GP and (5) a 6-hour training to prepare GPs for consultations in terms of SDM.27

The ISDM-P addresses various facilitators and barriers of SDM implementation.5 35 36 In the patient-teaching session, MAs provided evidence-based risk information and assured that the patients understood it by using question cards to identify knowledge gaps and to repeat content, if necessary. Further, they helped patients to set individual treatment goals and to document them on the patient-held sheet. The sheet ensured that individual patient set goals were discussed in the subsequent patient–physician encounter. Finally, both, patients and GPs documented their common goals on the patient-held sheet. A copy remained in the patient record. Please refer to online supplementary data S3 for details on the sheet—note that this has been translated from German to English.

Comparison

The control group received standard care supplemented with a brief extract of the patients’ version of the German National Disease Management Guidelines on the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes, with a link to the full version of the guideline.37

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was adherence to antihypertensive or statin therapy, operationalised as adherence to prescribed medication as documented in the patients’ records at the 6-month follow-up. Our hypothesis was that patients would be more adherent when they defined personal treatment goals together with their healthcare professionals. For more details on selection of the primary endpoint, please refer to the protocol.27

A blinded external study assistant conducted telephone interviews with all patients to assess the primary endpoint after 6 months. She was specifically trained by the psychologist who coauthored the study (KL) to perform the interview. A standardised interview guide was used. Patients were considered to have been adherent if their answers were consistent with the prescription documented in the patients’ record.

Secondary endpoints included: (1) informed choices about statin treatment, blood pressure control, glucose control and smoking cessation; (2) risk knowledge; (3) realistic expectations about individual heart attack risks and effects of preventive options; (4) achievement and (5) prioritisation of treatment goals.27

The adapted multidimensional parameter informed choice38 tests for adequate knowledge (eg, correctly answering 8 out of 11 items of the validated questionnaire27) and achievement of treatment goals. A patient with adequate knowledge and who had achieved the personal treatment goal was considered as having made an informed choice. How well the treatment goals (including prioritisation of goals) of patients and GPs matched was assessed as an indicator of SDM. In addition, changes in medication prescriptions and clinical parameters, including HbA1c levels, cholesterol and blood pressure, was assessed from baseline to follow-up.

Sample size

It was assumed that 80% of patients in the ISDM-P group would adhere to prescriptions of antihypertensive and statin medication, as compared with 60% of the control group.27 An intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.03 and a mean cluster size of 13 patients were estimated. Using estimations of 1.36 for design effect, 80% power, 5% significance level and a 20% drop-out rate, the calculated sample size was 306 patients distributed over 24 practices (clusters).

Randomisation and blinding

Concealed randomisation was performed in blocks of four practices using a computer-generated allocation sequence, after patient recruitment and collection of baseline data, by the Centre for Clinical Studies at the Jena University Hospital. Blinding of practices was not feasible. However, an attempt to conceal allocation for patients was made. At follow-up, patients were asked ‘In your opinion, did you receive new or more-of-the-same information?’ Assessment of the primary endpoint, data entry and analyses were kept blinded against study allocation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by intention to treat.27 For main endpoints, missing data were imputed using the method of multiple imputations. Therefore, an extensive set was used of baseline covariates and, when appropriate, outcome-specific variables, that is, blood pressure, age, gender, graduation status and prescribed medication.

Generalised mixed models were fitted to compare the groups with respect to rates of adherence, informed choice and individual goal achievement, with intervention as a fixed effect and practices as a random effect. Cluster-adjusted OR and 95% CIs were calculated. We used linear mixed models to compare study groups regarding average differences between planned and achieved values of blood pressure and HbA1c, the level of knowledge, realistic expectations and change of clinical parameters (from baseline to 6 months follow-up). Cluster-adjusted mean differences with 95% CI were calculated. No central laboratory analysis was carried out for the study, as practices contract various laboratories.

Deviations from the protocol are described in online supplementary data S1.

Process evaluation

Barriers and facilitators of implementing the ISDM-P in routine care were identified using the documentation from the MAs for the teaching sessions as well as interviews with MAs and GPs of each ISDM-P practice. Interviews focused on workload and attitudes towards the ISDM-P as well as on experiences with teaching, such as organisational aspects or use of teaching material.

Results

Of the 307 invited general practices, 22 were recruited; of the 363 eligible patients, 279 participated (with informed consent). Eleven practices (with 151 patients) were randomised to ISDM-P and 11 practices (with 128 patients), to standard care (figure 1). Baseline characteristics were comparable between groups (table 1). Fifteen patients of the ISDM-P group did not participate in the teaching session and eight were lost to follow-up. In the control group, three patients were lost to follow-up. About half of the patients in both groups thought they received the usual information. More patients in the ISDM-P group responded that they received new information (38% compared with 19%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | ISDM-P group (n=151) | Control group (n=128) |

| Women | 67 (44.4) | 59 (46.1) |

| Age, years | 59.5 (6.5) | 58.7 (7.9) |

| Duration of diabetes, years* | 8.5 (6.5) | 7.5 (6.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg† | 140 (15.1) | 140 (16.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg† | 81 (8.9) | 84 (8.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2‡ | 33.6 (5.3) | 31.5 (6.7) |

| HbA1c, %§ | 7.0 (0.7) | 7.0 (1.0) |

| Total cholesterol†, mmol/L | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.1) |

| High-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 3.2 (0.9) | 3.4 (1.0) |

| Smoker (%)** | 29 (19.2) | 18 (14.5) |

| Diagnosis hypertension (%)† | 134 (88.7) | 115 (90.6) |

| Medication for blood pressure control (%) | 129 (85.4) | 104 (81.3) |

| Medication for glucose control | 124 (82.1) | 95 (74.2) |

| Insulin | 36 (23.8) | 28 (21.9) |

| Metformin | 111 (73.5) | 88 (68.8) |

| Sulfonylurea | 21 (13.9) | 10 (7.8) |

| Other antidiabetic agents | 52 (34.4) | 40 (31.3) |

| Statin medication | 50 (33.1) | 41 (32.0) |

| Participation in teaching session for hypertension†† (%) | 28 (21.1) | 11 (10.1) |

| Graduation | ||

| None | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| Junior high school | 29 (19.2) | 24 (18.8) |

| High school | 93 (61.6) | 86 (67.2) |

| Qualification for technical college or university | 28 (18.5) | 17 (13.3) |

Values are given as patient number (percentage) or as means (SD).

*ISDM-P n=151, control group n=125.

†ISDM-P n=151, control group n=127.

‡ISDM-P n=150, control group n=126.

§ISDM-P n=151, control group n=128.

¶ISDM-P n=150, control group n=117.

**ISDM-P n=151, control group n=124.

††Patients with diagnosis of hypertension, ISDM-P n=133, control group n=109.

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; ISDM-P, informed shared decision-making programme.

Primary outcome

At follow-up, 218 patients were prescribed antihypertensive drugs and 107 patients, statins. Adherence rates to antihypertensive and statin medications were high for both groups, with no difference between groups (table 2). Missing data did not affect the results.

Table 2.

Primary endpoint: adherence to antihypertensive or statin therapy

| ISDM-P group | Control group | Adjusted OR (95% CI); p values |

MI: adjusted OR (95% CI); p values | ICC | |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 96/118 (81.4) | 71/90 (78.9) | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.6); 0.696 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4); 0.812 | 0.176 |

| Statins | 51/58 (87.9) | 43/45 (95.6) | 0.4 (0.1 to 2.0); 0.271 | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.4); 0.139 | 0.000 |

Values are given as patient number (percentage).

ICC, intracluster correlation coefficient; ISDM-P, informed shared decision-making programme; MI, multiple imputation (n=279).

Secondary outcomes

More ISDM-P patients made informed choices regarding statin intake, blood pressure control and glucose control (table 3). There were less than 20% smokers in both groups. We found no difference in informed choices regarding smoking cessation. A total of 136 ISDM-P patients (90%) and 109 control group patients (85%) completed the knowledge test (score of 0–11). The mean score was 6.96 for ISDM-P, versus 2.86 for the control group (adjusted mean difference 4.06 (95% CI 2.96 to 5.17); p<0.001). The mean score for the domain realistic expectations (score of 0–5) was 3.09 for ISDM-P patients, versus 0.92 for standard care patients (2.18, 95% CI 1.67 to 2.69; p<0.001) (online supplementary data S4). Significantly more ISDM-P patients had adequate risk knowledge (table 3).

Table 3.

Informed choice and adequate knowledge

| ISDM-P group | Control group | Adjusted OR (95% CI); p values | MI: adjusted OR (95% CI); p values |

|

| Adequate knowledge* | 61/136 (44.9) | 3/109 (2.8) | 29.3 (6.9 to 124.6); <0.001 | 21.4 (6.8 to 67.4); <0.001 |

| Informed choice: statins | 43/128 (33.6) | 3/105 (2.9) | 16.6 (4.4 to 63.0); <0.001 | 6.2 (2.4 to 16.0); <0.001 |

| Informed choice: blood pressure | 50/129 (38.8) | 3/109 (2.8) | 22.2 (5.3 to 93.3); <0.001 | 10.0 (3.3 to 30.4); <0.001 |

| Informed choice: HbA1c | 57/134 (42.5) | 3/109 (2.8) | 26.0 (6.5 to 104.8); <0.001 | 11.5 (4.0 to 33.1); <0.001 |

| Informed choice: smoking | 3/23 (13.0) | 0/16 (0) | 5.1 (0.2 to 135.1); 0.322 | – |

Values are given as patient number (percentage).

*At least 8 out of 11 questions were correctly answered.

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; ISDM-P, informed shared decision-making programme; MI, multiple imputation (n=279).

For estimating personal heart attack risk, 131 ISDM-P and 96 standard care patients participated. The absolute difference of the patient estimated individual risks and objective risks was greater in the control group (5.5% vs 31.1%; adjusted difference –25.6% (95% CI –30.4% to –20.8%); p<0.001). This result was confirmed after multiple imputation of missing data. Notably, most patients in the control group overestimated their personal heart attack risk (online supplementary data S5 and S6).

There was no difference between groups with respect to meeting treatment goals at follow-up. Most patients in both groups achieved their goals regarding statins (85.8% of ISDM-P patients vs 87% of control group patients), blood pressure (93.7% vs 90%) and HbA1c (94.7% vs 89.1%) (online supplementary data S7). No substantial changes within groups from baseline to follow-up were observed for HbA1c levels, systolic blood pressure values, total cholesterol levels, low-density lipoprotein levels or medication prescriptions (data not shown).

Prioritisation of treatment goals differed significantly between groups. More ISDM-P patients prioritised blood pressure control rather than HbA1c targets (28% vs 12%; p<0.015) (online supplementary data S8).

Matching of treatment goals of GPs and patients were higher for the ISDM-P group (table 4). Significant differences in favour of the ISDM-P group were found for treatment goals regarding blood pressure values, HbA1c-levels and the prioritised goal. These results remained unchanged after multiple imputation of missing data.

Table 4.

Match of treatment goals between physicians and patients

| Treatment goal | ISDM-P group | Control group | Adjusted difference (95% CI); p values | MI: adjusted difference (95% CI); p values |

| Blood pressure* | 3.06 mm Hg (5.21) | 6.89 mm Hg (6.94) | –4.0 mm Hg (–6.6 to –1.4); 0.005 | –3.1 (–5.6 to –0.5); 0.019 |

| HbA1c† | 0.26% (0.33) | 0.49% (0.49) | –0.2 (–0.4 to –0.1); 0.003 | –0.2 (–0.39 to –0.05); 0.012 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI); p values |

MI: adjusted OR (95% CI); p values | |||

| Statins | 114/127 (89.8) | 81/104 (77.9) | 2.4 (0.9 to 6.2); 0.077 | 1.9 (0.7 to 4.8); 0.181 |

| Stop smoking | 9/17 (52.9) | 6/9 (66.7) | 0.5 (0.1 to 4.0); 0.537 | 0.6 (0.1 to 3.6); 0.561 |

| Prioritised goal | 92/104 (88.5) | 45/79 (57.0) | 6.5 (3.0 to 14.4); <0.001 | 2.6 (1.3 to 5.2); 0.009 |

Values are given as patient number (percentage) unless stated otherwise.

*Adjusted mean difference between patients’ treatment goals and physicians’ treatment goals; values are means (SD); ISDM-P n=127, control group n=95.

†Adjusted mean difference between patients’ treatment goals and physicians’ treatment goals; values are means (SD); ISDM-P n=133, control group n=95.

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; ISDM-P, informed shared decision-making programme; MI, multiple imputation (n=279).

Process evaluation

Characteristics of practices, such as numbers of employed MAs, GPs and patients, were comparable between groups (online supplementary data S9).

ISDM-P patient teaching module

Overall, 35 teaching sessions were provided by ISDM-P practices. MAs conducted 2–6 sessions that lasted between 50 and 120 min. Group sizes varied from one to seven patients. MAs stated that they felt well prepared for the ISDM teaching module. Role playing and question cards related to the content of the ISDM-P were identified as facilitators for training success. Before the study, MAs were unfamiliar with risk communication. Some MAs and some patients indicated that there was too much statistics to explain/understand, while a few patients stated that there was not enough information about statistics. Overall, MAs felt that patients were appreciative for the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process and to define their own treatment goals.

ISDM-P consultations

Patients consulted their GPs directly after the teaching session or within 1–3 weeks afterwards. The consultations lasted between 5 and 20 min (mean 11.4 min). GPs stated that the patients had been well prepared for decision-making by their MAs, which was ‘better than expected’ and ‘better than usual’. They experienced changes in communication following the ISDM-P teaching module. One GP stated that former consultations were more ‘instructive, demanding and in some ways authoritarian’, and found that after training, patients and professional teams ‘meet on an equal footing’.

Workload

MAs described the efforts of training and practising for the teaching module as similar as for standard DMP patient education modules. Most GPs and MAs described the overall workload as appropriate. GPs considered the intended distribution of work within the team as helpful and reduced workload. Most practices would provide the ISDM-P in routine care if it was covered by health insurances. See online supplementary data S9 for more details.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

Results from our single centre proof-of-concept RCT21 were confirmed in this multicentre cluster RCT. The programme could be translated from a university-based diabetes centre to everyday primary care. ISDM-P patients were more likely to make informed choices, while the standard care control group did not make informed decisions. The ISDM-P group showed increased knowledge and realistic expectations regarding their individual cardiac risk and probabilities of the benefits and harms of preventive treatment options. Treatment goals between patients and their physicians were more matched for the intervention group. The patient-held documentation sheet of personal treatment objectives supported patients and GPs in deliberating treatment goals and preferences. In fact, better informed patients appeared to trigger more rational evidence-based goal setting among physicians. Contrary to our predefined hypotheses, adherence to medication was very high overall in this study population, making further improvements undetectable. Overall, we believe that the ISDM-P was successfully implemented in the general practices.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Our study has several strengths. The intervention has been developed and evaluated according to the United Kingdom Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions.28 Efficacy was demonstrated in an RCT under high-fidelity conditions.21 Findings of the RCT and qualitative process data were used to optimise the ISDM-P.27 A recent publication has reviewed important barriers of SDM.5 Our programme already addresses these barriers.

In order to facilitate integration into everyday practice, the structure and duration of the ISDM-P teaching session were adapted to standard teaching modules of the DMP.22–25 The cluster RCT was meticulously designed and conducted with a low drop-out rate. Additional qualitative methods were used to gain insight into implementation processes.

The weaknesses of the study include the inability to blind the study for the healthcare team for study allocation, due to the nature of the intervention. It also remains unclear to what degree patients were kept blinded. Further, we could not document the extent of SDM. There is no gold standard to quantify patient involvement,27 39 and the use of decision aids does not accurately reflect SDM.40 Videotaping and available instruments, such as MAPPIN’SDM, are not applicable for routine care conditions.41 Thus, we had to define surrogate parameters. Risk knowledge is a prerequisite of informed SDM. The proof-of-concept RCT21 showed that patients with standard care lack the necessary risk knowledge. Therefore, we used knowledge and informed choice as secondary endpoints. We hypothesised that successful ISDM would enable more patients to set and achieve realistic and personally defined treatment goals. However, patients were already well controlled at the beginning of the study. Study participants were followed in the German DMP for type 2 diabetes. All had received structured education and were closely monitored. The proof-of-concept RCT indicated lower adherence rates to statin prescriptions in the standard care group. Adherence is a patient relevant endpoint that may reflect successful ISDM when it is based on adequate knowledge and mutual agreement on treatment goals between patients and health professionals. We hypothesised that patients would be more adherent to medication when prescriptions were based on SDM principles. However, in the present cluster RCT, adherence to antihypertensive medication and statins was very high already under standard care. Patients’ self-reported adherence to medication uptake was used to assess the primary endpoint. Telephone interviews were conducted independently from practices, but socially desirable answers cannot be completely ruled out. The interviewer asked patients to read out the substance that was labelled on the medication boxes. To do that, patients had to have the medication box at home. No changes from baseline to follow-up were observed for prescription rates or clinical parameters (such as levels of HbA1c, blood pressure and cholesterol). Thus, it is very likely that adherence was already high at baseline. Generalisability of our results to other healthcare systems remains speculative. Our study participants had unexpectedly high adherence rates to prescribed medications and overall good control of diabetes and hypertension. This might be a result of diabetes care within the DMP for patients with type 2 diabetes in Germany. In populations with lower adherence rates, the ISDM-P could presumably improve adherence to medication. Our patient-held documentation sheet improved matching of treatment goals between patients and GPs and therefore might be used as a surrogate indicator for SDM. This sheet is an integral part of the intervention for supporting patient participation and, at the same time, a tool for the documentation of common treatment goals.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies, discussing important differences in results

The statin choice decision aid was tested regarding statin adherence in a specialised clinic,14 one primary care centre13 and several primary care practices in Spain.15 Improvement of adherence was only found in the specialised clinic.14 The diabetes medication choice decision aid had no impact on adherence,17 while one study even reported a better outcome in the control group.16 In all publications, adherence rates were very high already under standard care. This is consistent with our study.

In a recent cluster RCT from the Netherlands (OPTIMAL), an SDM intervention also aimed at enhancing patients’ achievement of treatment goals.12 Patients were asked to choose between an intensive treatment strategy according to the ADDITION protocol and a less intensive treatment based on guideline recommendations. The findings showed no significant difference between the groups. Almost half of the patients in the intervention group switched from less intensive to intensive treatment.12 However, benefits from intensifying therapy in type 2 diabetes are questionable. In our previous RCT on the ISDM-P, more patients achieved their HbA1c level goals because they set slightly higher HbA1c targets after the teaching session.21 We offered and supported patients to prioritise and set realistic treatment goals. GPs of the OPTIMAL trial found the decision aid helpful, but it remains unclear if patients understood the information.12

Most of the ISDM-P consultations with the GP did not take longer than usual consultations, with a mean duration of about 11 min. The implementation trial of the statin choice decision aid in Spain reported consultation times of almost 20 min without significant differences between intervention and control groups.15 In our study, GPs just had to perform the last steps of the SDM process, as patients had been well prepared for decision-making by MAs. Hence, GPs could discuss four health topics—blood glucose, blood pressure, statin use and smoking—and related treatment options with their patients in a single encounter. The duration of the group teaching session provided by MAs was comparable to other DMP teaching sessions.

Recently, Ballard et al assessed the routine use of the statin choice decision aid and the diabetes medication choice decision aid in a tertiary care centre under routine care.40 Half of the clinicians used the statin choice decision aid and 9% the medication choice decision aid. Reasons for not using the material were lack of awareness that the tools were available, time constraints and attitudinal barriers, for example, clinicians found the decision aids not helpful or not accurate.40 Recommendations to address such barriers are workshops to improve SDM skills, development of brief evidence-based consultation tools, interventions to prepare patients in decision-making and the development of measurements to be used in practice to identify knowledge gaps and preferences.5 Our ISDM intervention already addresses all these aspects. The ISDM-P training included a demonstration of a patient-teaching session and role play in order to help teams gain more insight into differences between usual counselling and SDM-based consultations. Our training took longer than trainings in other studies, but this time duration was perceived as appropriate by participants.

Meaning of the study: possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policy-makers

In our study, we determined that patients under standard care did not have adequate risk knowledge to make informed decisions. Healthcare providers do not have access to education and patient information material which fulfil the criteria for evidence-based health information. The ISDM-P remedies this: it not only provides understandable and relevant risk information to healthcare personnel and patients, it also enables a patient–physician communication on equal footing and helps patients and GPs to pursue common treatment goals as recommended in DMP guidelines. Our study shows that the ISDM-P can be integrated in everyday practice without large extra effort. It meets the criteria to be covered by health insurance companies.

Unanswered questions and future research

Further research will focus on extending the ISDM-P concept to other clinical decisions. In particular, drug facts boxes on the increasing number of oral antidiabetic agents should be made available. Structured treatment and teaching programmes need to be updated and optimised based on criteria for evidence-based patient information and SDM.22 25 42 Web-based formats allowing individual training and exchange with healthcare professionals have to be developed. This will also allow a more personalised selection of teaching modules on diabetes or hypertension care.

Current clinical practice guidelines do not provide well-structured information on benefits and harms of medication or other treatments that could readily be used within consultations with patients. Fact boxes or other decision tools should be considered in guideline development.3 43 Finally, open access trainings in evidence-based medicine, risk information and SDM for healthcare providers are required. Maintaining and updating an entire ISDM treatment and teaching programme will require an up-to-date online platform for patients and healthcare providers.

The implementation of the ISDM-P concept would meet national and international guideline recommendations as well as the patients’ ethical and legal rights on true involvement in decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the medical assistants, physicians and participating patients of all 22 primary care practices. We also thank Susanne Kählau-Meier for her valuable support in data collection and administration as well as Veronica A. Raker for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was carried out in collaboration between all authors. SB and IM designed the study. SB and KL designed and tested the provider training. SB, NK and UAM were involved in the planning, coordination and management of data acquisition at the study sites (primary care practices). TL did the statistical planning and analyses of the study. SB and IM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NK, KL and UAM contributed to the draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was funded by the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD) on behalf of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). NK’s salary has been partly financed by the non-profit association “Diabeteszentrum Thüringen e.V.” (Diabetes Centre Thuringia).

Disclaimer: The EFSD and the Diabetes Centre Thuringia had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: NK reports grant from the Diabetes Centre Thuringia during the conduct of the study.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Association of Thuringia in April 2014 (ref: 29739/2014/31).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The corresponding author can be contacted to forward request for data sharing.

References

- 1. German Medical Association, National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies. Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Therapie des Typ-2-Diabetes – Langfassung. 2013. http://www.leitlinien.de/nvl/diabetes/therapie (Accessed 19 Mar 2018).

- 2. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140–9. 10.2337/dc14-2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rutten G, Alzaid A. Person-centred type 2 diabetes care: time for a paradigm shift. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30193-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Gionfriddo MR, Ospina NS, et al. Shared decision making in endocrinology: present and future directions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:706–16. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00468-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ 2017;357:j1744 10.1136/bmj.j1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agoritsas T, Heen AF, Brandt L, et al. Decision aids that really promote shared decision making: the pace quickens. BMJ 2015;350:g7624 10.1136/bmj.g7624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scholte op Reimer WJ, Moons P, De Geest S, et al. Cardiovascular risk estimation by professionally active cardiovascular nurses: results from the Basel 2005 Nurses Cohort. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006;5:258–63. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mühlhauser I, Kasper J, Meyer G. Federation of European Nurses in Diabetes. Understanding of diabetes prevention studies: questionnaire survey of professionals in diabetes care. Diabetologia 2006;49:1742–6. 10.1007/s00125-006-0290-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W, Kurz-Milcke E, et al. Helping doctors and patients make sense of health statistics. Psychol Sci Public Interest 2007;8:53–96. 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2008.00033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montori VM, Kunneman M, Brito JP. Shared decision making and improving health care: the answer is not in. JAMA 2017;318:617–8. 10.1001/jama.2017.10168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:Cd001431 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Den Ouden H, Vos RC, Rutten G. Effectiveness of shared goal setting and decision making to achieve treatment targets in type 2 diabetes patients: a cluster-randomized trial (OPTIMAL). Health Expect 2017;20:1172–80. 10.1111/hex.12563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mann DM, Ponieman D, Montori VM, et al. The statin choice decision aid in primary care: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80:138–40. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weymiller AJ, Montori VM, Jones LA, et al. Helping patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus make treatment decisions: statin choice randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1076–82. 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perestelo-Pérez L, Rivero-Santana A, Boronat M, et al. Effect of the statin choice encounter decision aid in Spanish patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:295–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mullan RJ, Montori VM, Shah ND, et al. The diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1560–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karagiannis T, Liakos A, Branda ME, et al. Use of the diabetes medication choice decision aid in patients with type 2 diabetes in Greece: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012185 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mathers N, Ng CJ, Campbell MJ, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a patient decision aid to improve decision quality and glycaemic control in people with diabetes making treatment choices: a cluster randomised controlled trial (PANDAs) in general practice. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001469 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denig P, Schuling J, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, et al. Effects of a patient oriented decision aid for prioritising treatment goals in diabetes: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014;349:g5651 10.1136/bmj.g5651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lenz M, Kasper J, Mühlhauser I. Development of a patient decision aid for prevention of myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetes - rationale, design and pilot testing. Psychosoc Med 2009;6:Doc05 10.3205/psm000061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buhse S, Mühlhauser I, Heller T, et al. Informed shared decision-making programme on the prevention of myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009116 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gruesser M, Bott U, Ellermann P, et al. Evaluation of a structured treatment and teaching program for non-insulin-treated type II diabetic outpatients in Germany after the nationwide introduction of reimbursement policy for physicians. Diabetes Care 1993;16:1268–75. 10.2337/diacare.16.9.1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kronsbein P, Jörgens V, Mühlhauser I, et al. Evaluation of a structured treatment and teaching programme on non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Lancet 1988;2:1407–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90595-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gruesser M, Hartmann P, Schlottmann N, et al. Structured treatment and teaching programme for type 2 diabetic patients on conventional insulin treatment: evaluation of reimbursement policy. Patient Educ Couns 1996;29:123–30. 10.1016/0738-3991(96)00941-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Müller UA, Müller R, Starrach A, et al. Should insulin therapy in type 2 diabetic patients be started on an out- or inpatient basis? Results of a prospective controlled trial using the same treatment and teaching programme in ambulatory care and a university hospital. Diabetes Metab 1998;24:251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Busse R. Disease management programs in Germany’s statutory health insurance system. Health Aff 2004;23:56–67. 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buhse S, Mühlhauser I, Kuniss N, et al. An informed shared decision making programme on the prevention of myocardial infarction for patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care: protocol of a cluster randomised, controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:43 10.1186/s12875-015-0257-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, et al. Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials 2013;14:15 10.1186/1745-6215-14-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci 2017;12:21 10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ 2017;356:i6795 10.1136/bmj.i6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Busse R, Blümel M, Knieps F, et al. Statutory health insurance in Germany: a health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. Lancet 2017;390:882–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31280-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fuchs S, Henschke C, Blümel M, et al. Disease management programs for type 2 diabetes in Germany: a systematic literature review evaluating effectiveness. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:453–63. 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. German Medical Association, National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies. Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Diabetes – Strukturierte Schulungsprogramme – Langfassung. 2012. http://www.leitlinien.de/nvl/diabetes/schulungsprogramme (Accessed 19 Mar 2018).

- 35. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:291–309. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;7:CD006732 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. German Medical Association, National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies. PatientenLeitlinie zur Nationalen VersorgungsLeitlinie, Therapie des Typ-2-Diabetes. 2015. http://www.leitlinien.de/nvl/diabetes/therapie (Accessed 19 Mar 2018).

- 38. Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect 2001;4:99–108. 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00140.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gärtner FR, Bomhof-Roordink H, Smith IP, et al. The quality of instruments to assess the process of shared decision making: A systematic review. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191747 10.1371/journal.pone.0191747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ballard AY, Kessler M, Scheitel M, et al. Exploring differences in the use of the statin choice decision aid and diabetes medication choice decision aid in primary care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017;17:118 10.1186/s12911-017-0514-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kasper J, Heesen C, Köpke S, et al. Patients’ and observers’ perceptions of involvement differ. Validation study on inter-relating measures for shared decision making. PLoS One 2011;6:e26255 10.1371/journal.pone.0026255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mühlhauser I, Sawicki PT, Didjurgeit U, et al. Evaluation of a structured treatment and teaching programme on hypertension in general practice. Clin Exp Hypertens 1993;15:125–42. 10.3109/10641969309041615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mühlhauser I, Meyer G. Evidence base in guideline generation in diabetes. Diabetologia 2013;56:1201–9. 10.1007/s00125-013-2872-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024004supp001.pdf (153.3KB, pdf)