Abstract

Malaria is associated with significant microcirculation disorders, especially when the infection reaches its severe stage. This can lead to a range of fatal conditions, from cerebral malaria to multiple organ failure, of not fully understood pathogenesis. It has recently been proposed that a breakdown of the glycocalyx, the carbohydrate-rich layer lining the vascular endothelium, plays a key role in severe malaria, but direct evidence supporting this hypothesis is still lacking. Here, the interactions between Plasmodium falciparum infected red blood cells (PfRBCs) and endothelial glycocalyx are investigated by developing an in vitro, physiologically relevant model of human microcirculation based on microfluidics. Impairment of the glycocalyx is obtained by enzymatic removal of sialic acid residues, which, due to their terminal location and net negative charge, are implicated in the initial interactions with contacting cells. We show a more than twofold increase of PfRBC adhesion to endothelial cells upon enzymatic treatment, relative to untreated endothelial cells. As a control, no effect of enzymatic treatment on healthy red blood cell adhesion is found. The increased adhesion of PfRBCs is also associated with cell flipping and reduced velocity as compared to the untreated endothelium. Altogether, these results provide a compelling evidence of the increased cytoadherence of PfRBCs to glycocalyx-impaired vascular endothelium, thus supporting the advocated role of glycocalyx disruption in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Keywords: human umbilical vein endothelial cells, glycocalyx, Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence, microfluidics

1. Background

Malaria is the most widespread mosquito-borne infectious disease in humans and it is caused by single-celled Plasmodium parasites. Most of the cases of fatal malaria are due to Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), a species with a mortality of 15–20% mostly among children in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is endemic [1–4]. Malaria is transmitted through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito in the form of sporozoites. The asexual reproduction of the sporozoites produces free forms of parasite (‘merozoites’); once released in the blood stream, these proceed through rounds of intracellular growth, egress and invasion, greatly amplifying their number by clonal divisions. The ability of merozoites to invade cells is limited to a few minutes after parasite egress from red blood cells (RBCs) [5,6]. The parasites grow intracellularly in the blood stage for around 48 h through ring, trophozoite, and schizont phases [1,2,7–9].

The disease state is characterized by microcirculation disorders, including mechanical obstruction of small blood vessels connected to the progressive changes in Pf-infected RBC (PfRBC) shape, size, and structure during the intraerythrocytic cycle [10,11] compared to healthy conditions [12,13]. In severe malaria (SM), mature PfRBCs change their membrane properties and develop the ability to bind to endothelial cells of peripheral blood vessels (sequestration) [1,14], to adhere to nearby nonparasitized RBCs (HRBCs) (rosetting) [15] and/or to other PfRBCs (auto-agglutination) [16]. Such phenomena cause the restriction of the vascular lumen, leading to anaemia and fatal complications due to the blockage of the microcirculatory flow and the lack of PfRBC clearance by the spleen [17].

Malaria cytoadherence has been widely investigated both by experimental research and mathematical simulations. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed, such as changes of RBC rigidity [1,2,18], induction to release of pro-inflammatory receptors [19], binding of PfRBCs to specific adhesion receptors on endothelial cells [20], and activation of endothelial receptors [21,22]. Due to the complex structure of microvasculature, most experimental studies have taken a simplifying approach, addressing PfRBC adhesion and sequestration in flow chambers coated by a choice of the adhesion molecules likely involved in the adhesion pathway (i.e. CD36, V-CAM1, I-CAM1) [23–26]. In some studies, the cytoadhesion of PfRBCs at schizont stage under physiological flow conditions was also associated with rolling, a behaviour similar to the one of leucocytes in the first step of extravasation during acute inflammation [27–29]. PfRBC cytoadhesion under flow has also been investigated by computational models as a function of relevant parameters, such as cell stiffness, flow conditions, tube dimensions and haematocrit. Fedosov et al. [29–32], investigating the adhesion of PfRBCs in cylindrical capillaries, identified several modes of adhesive behaviour: solid adhesion, slow slipping along the wall, and intermittent flipping. These computational studies shed critical information on the complex physical interactions coupling fluid dynamics to cell membrane deformability, but they lack biochemical detail at the microscopic level. Despite these significant insights, the mechanisms at the base of PfRBC binding to endothelial cells remain unclear and are still under debate.

Recently, it has been suggested [33] that a breakdown of the glycocalyx, the carbohydrate-rich layer lining the vascular endothelium, might play a key role in SM. Endothelial remodelling in malaria may result from local inflammation and activation of enzymes inducing glycocalyx shedding, such as thrombin and plasmin. Removal of the outer glyocosaminoglycans may allow interaction of PfRBCs with glycoproteins, such as CD36, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and endothelial protein C receptor, which are located at a deeper level in the glycocalyx and are involved in the cytoadhesion pathway. In addition, PfRBCs themselves may also directly bind to the endothelium through glycosaminoglycans, such as heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate [34,35], and contribute to endothelium remodelling by generating components with sheddase-like functions [33,36].

In vitro models are especially relevant to assess the putative role of glycocalyx in SM pathogenesis, since they allow the use of human materials and controlled perturbations. Nevertheless, the application of such models has been hindered by the experimental difficulty to obtain a mature glycocalyx in vitro. Protocols to observe endothelial glycocalyx in vitro by confocal microscopy under static [37] and flow conditions [38] have been recently published. However, to the best of our knowledge, no reports describing models of microcirculation to study the effect of glycocalyx on malaria in vitro are available in the literature.

Here, we describe a microfluidic organ-on-chip device that mimics the lumen of a blood microvessel using small sample volumes and allows one to observe PfRBC adhesion onto endothelial cells under flow rates in the physiological range of microcirculation. The coupling of microfluidics and live microscopy provides a reliable in vitro model for the investigation of cytoadherence in Pf malaria under physiological conditions. By selectively removing the sialic acids of the endothelial glycocalyx via enzymatic treatment, we found that malaria infected cells become more adhesive with respect to healthy ones, thereby showing that the vascular endothelial glycocalyx strongly regulates cytoadherence.

2. Methods

2.1. Healthy red blood cells

Human blood was obtained from healthy volunteers. RBCs were separated from other blood components by centrifugation (as described in detail in electronic supplementary material S1) and suspended in wash medium at a 1 : 1 ratio by volume to have a 50% haematocrit (Hct) suspension. The latter was placed at 4°C for storage for up to 7–10 days.

2.2. Plasmodium falciparum culture

Pf ITO4 strain [39] knob positive was provided by Drs V.L. Lew and T. Tiffert (Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge). ITO4 parasites were cultured in fresh human RBCs (prepared as described in §2.1) under low-oxygen atmosphere (1% O2, 3% CO2, and 96% N2), and the culture medium (wash medium supplemented with 0.5% AlbuMAX II, Sigma-Aldrich) was changed daily according to standard protocols [40,41]. For experiments requiring a low level of parasitaemia, around 5%, the Hct was maintained at 5% and the malaria culture was synchronized through the sorbitol lysis method [42] to keep the development stage of the parasites within a narrow range (trophozoites and schizonts). For experiments requiring an elevated number of highly synchronous infected red blood cells (PfRBCs), we followed the protocol of Radfar et al. [43], using low Hct of 1–1.5% and the sorbitol synchronization method to shorten the parasite cycle window to 4–6 h, therefore increasing the parasitaemia to 15–20%. The parasitaemia was assessed by microscopic inspection of Giemsa-stain (Sigma-Aldrich) blood smears.

2.3. Growth of human umbilical vein endothelial cells in microfluidic channels

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, from Sigma-Aldrich) were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator on uncoated tissue-culture polystyrene flasks (see electronic supplementary material S2 for details) until cell confluency of 85% was reached. A suspension of HUVECs (density of about 106 ml−1) was transferred from the flask and seeded into the microchannels (commercially available from Ibidi as μ-Slide VI) used to perform controlled flow experiments.

Each microchannel was coated with collagen type IV and had a rectangular geometry with height (h) 0.4 mm, width (w) 3.8 mm, and length (l) 17 mm.

A volume of 60 µl of HUVEC suspension was quickly released into each channel of the slide to cover its entire surface. After 2–3 h, cells were already attached to the bottom surface, and fresh endothelial cell growth medium (ECGM) was added to the reservoir of the flow chamber. Cells grew in the incubator for 1–2 days until confluency with a daily change of ECGM. Finally, a suspension of infected and healthy RBCs was flowed across the HUVEC monolayer, as illustrated in figure 1.

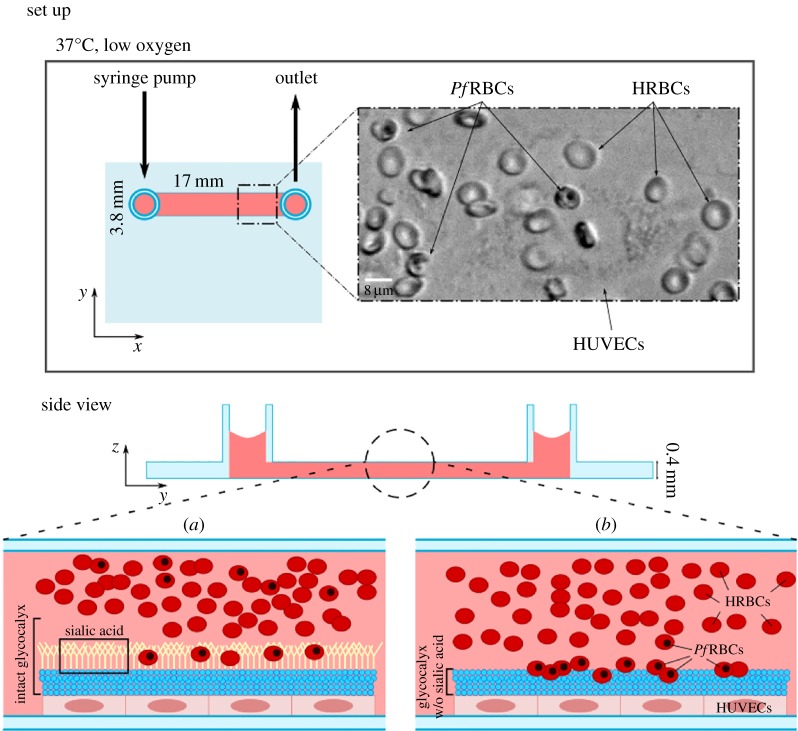

Figure 1.

Malaria infected cells become more adhesive with respect to HRBCs, and the vascular endothelial glycocalyx regulates adhesion. An organ-on-chip vascular endothelium of HUVECs is grown in a flow chamber, guaranteeing cell alignment and physiological glycocalyx. Cytoadherence experiments are performed in situ while perfusing cell suspension of HRBCs and PfRBCs at controlled flow rate using a syringe pump. The microfluidic chip has multiple channels (17 × 3.8 × 0.4 mm) used for on-chip controls. The whole set-up is placed in an incubator for the growth of the endothelium, and on the stage of an inverted microscope equipped with temperature control and gas supply for imaging. Experiments compare two conditions (schematically drawn in a and b): in (a) the integral glycocalyx covers all the endothelial surface, preventing the adhesion of all the healthy and most of the infected RBCs, and favouring the flow of RBCs across the endothelium; while in (b) the glycocalyx is largely removed by an enzymatic treatment, strongly affecting PfRBC cytoadherence. The loss of sialic acid layer on the outer portion of glycocalyx (b) leads to adhesion of PfRBCs to glycoproteins on the endothelial surface. It is possible that in vivo the partial damage or complete loss of glycocalyx could account for increased PfRBC adhesion and may cause blood flow problems such as hypoxia and inflammatory processes typical of SM. The glycocalyx structure is schematically represented in blue, and the sialic acid, as part of glycocalyx, is highlighted in yellow. RBCs are in red: PfRBCs can be distinguished from HRBCs because of the black spot representing the intracellular haemozoin, typical of late-stage infected RBCs.

2.4. Characterization of endothelium growth

HUVECs were grown in parallel microchannels at the same time as control, both in static and under shear stimulation for up to 8 days (see electronic supplementary material S3 for details). The steady shear stress applied was 2 Pa, a typical value in the human circulatory system [44].

Immunofluorescent staining of the glycocalyx was obtained by using Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA-Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes)), a lectin that binds to sialic acid, an important component of the endothelial glycocalyx [37].

The contribution of glycocalyx on malaria-induced cytoadherence was assessed via enzymatic digestion (details in electronic supplementary material S3) by incubation with neuraminidase, which cleaves the O-glycosidic bonds between the terminal sialic acids and the subterminal sugars [45] with a 95% specificity [46,47].

2.5. Microfluidic set-up for studying malaria adhesion on endothelium

PfRBCs were diluted to 0.1% Hct for imaging by adding culture medium and fresh uninfected erythrocytes (HRBCs), but keeping the level of parasitaemia at 20%, which is typical of SM [48]. This suspension was loaded into the microchannel using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) with flow rate regulation, as illustrated in the top view panel of figure 1.

To measure the velocity of HRBCs and PfRBCs at different wall shear stresses, videos were recorded at frame rate ranging from 10 to 300 frames per second depending on the flow rate and the size of the acquisition window (see electronic supplementary material S4 and S5).

3. Results

3.1. The microfluidic set-up provides a physiologically relevant model of microcirculation in vitro

The microfluidic set-up described in the previous section was used to create an organ-on-chip in vitro model mimicking the human vasculature microenvironment lined with HUVECs expressing the glycocalyx layer. The perfusion system, ensuring physiological flow conditions, allowed the growth of a viable HUVEC monolayer on the bottom plane of the flow chamber, with cell alignment and formation of endothelial glycocalyx. Our experiments compare two conditions: (i) the physiological case in which glycocalyx is produced on the top layer of HUVECs (as schematically shown in figure 1a) and (ii) the case in which glycocalyx is partly damaged by the loss of sialic acids (figure 1b), leading to enhanced cytoadherence of PfRBCs, as implicated in malaria infection.

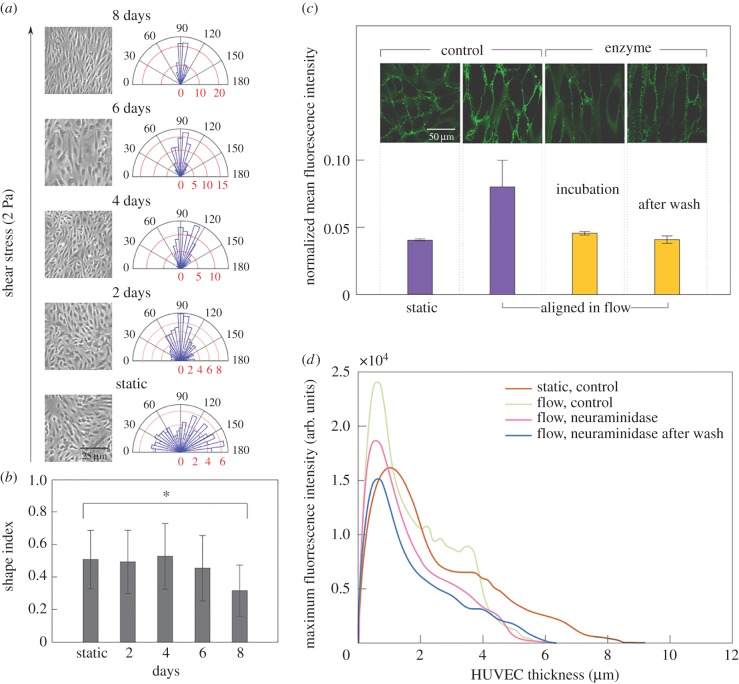

The growth of HUVECs under microfluidic perfusion leads to a physiologically relevant endothelium, as shown in the pictures reported in figure 2a: HUVECs adhere onto microchannel wall, forming a confluent monolayer of progressively oriented cells. Cell alignment along the flow direction was measured considering the angle between the major axis of the cell and the orthogonal direction to the flow. A polar plot was generated by distributing cell orientation angles into 25 equal slices (7.2° each) representing the whole range (0–180°). The microscopy images of HUVECs illustrate progressive cell alignment under 2 Pa flow over 8 days, as quantified in the polar plots from bottom to top. In static conditions, HUVECs are randomly orientated, while after just one day the cells start orienting along the flow direction (90o). In particular, after one day under flow about 80% of cells are in the 60°–120° range, and after 8 days all cells show orientation angles within the 60°–120° range.

Figure 2.

Growth of HUVECs in microfluidic perfusion culture leads to a physiological endothelium as well as enabling in situ imaging of adhesion. The microscopy images of HUVECs in (a) illustrate progressive cell alignment under 2 Pa flow over 8 days, quantified in the polar plots. HUVECs orient along the flow direction (90°), the red axis indicates the percentage of HUVECs in a slice. In static conditions HUVECs are randomly orientated, while already after one day in flow, about 80% of cells are in the 60°–120° range, and after 8 days all cells show orientation angles within the 60°–120° range. HUVEC elongation quantified by shape index (SI) [49,50] after 8 days in flow (b). The SI is 1 for a circle and 0 for a straight line. At day 8 the difference from static is statistically significant (p < 0.001). Error bars (such as in the following figures) represent the standard deviation of the measurements. (c) The glycocalyx expression is quantified through fluorescent plasma membrane staining WGA from three different fields of view: fluorescence is doubled in aligned HUVECs, whereas it is comparable to the non-aligned cells during and after neuraminidase treatment of HUVECs. The glycocalyx component was inferred by the WGA mean fluorescence intensity that stains only the HUVEC glycocalyx, normalized by the confocal microscopy gain, in static, flow, during incubation with neuraminidase, and after neuraminidase treatment. (d) The thickness of HUVEC layer is reduced in flow conditions. The plots show the distribution of the WGA intensity used to highlight the HUVEC surface as a function of their thickness in static, flow, during incubation with neuraminidase, and after enzyme wash. HUVECs under flow have thickness of about 6 µm, with no significant difference before and after the neuraminidase treatment, whereas the thickness of HUVECs in static is about 9 µm. Z-stacks videos of HUVEC monolayer growth in different conditions in parallel channels were recorded from the level of the microscope slide upward with steps of 0.2 µm. The thickness was finally calculated from the reconstruction of the surface of the endothelial layer, in which each point is the maximum fluorescence intensity value of WGA dye used to mark the surface of HUVECs.

HUVEC elongation can be quantified by the shape index (SI) of the cells, defined as

| 3.1 |

where A is the cell area, and P is the cell perimeter [49,50]. SI values range from 0 for a straight line to 1 for a perfect circle. In figure 2b the SI is plotted as a function of time. SI remains almost constant until day 5, then it starts decreasing on day 6, and by day 8 the difference from the static value is statistically significant (p < 0.001).

The glycocalyx expression and thickness were quantified by recording z-stack of images starting from the bottom surface of the microchannel, both in static and under flow, before and after enzyme treatment. Glycocalyx expression was quantified through fluorescent plasma membrane staining with WGA, a lectin that binds to sialic acids, the most commonly observed components of endothelial glycocalyx, responsible for the negative charge and generally used as representative of the glycocalyx presence [51–53]. In figure 2c, the value of the mean fluorescence intensity in each condition is normalized with respect to the confocal microscopy gain value chosen during acquisition. It can be observed that fluorescence doubles in aligned HUVECs, whereas it is comparable to the non-aligned cells during incubation with neuraminidase treatment, and after wash. This shows that perfusion of HUVECs under physiological flow conditions is essential to obtain higher cell alignment and glycocalyx expression as compared to static culture conditions.

Another parameter indicative of a physiologically relevant HUVEC monolayer is its thickness: we evaluated this by recording image z-stacks of HUVEC monolayers, from the surface of the microscope slide upwards in steps of 0.2 µm. The surface of the glycocalyx layer was reconstructed by taking at each point the thickness of the maximum fluorescence intensity value of the WGA dye. The plot in figure 2d shows the distributions of the WGA maximum fluorescence intensity as a function of thickness under static and flow conditions, during incubation with neuraminidase, and after enzyme wash. The width of these distributions shows that HUVECs under flow have thickness of about 6 µm, with no significant difference before and after the neuraminidase treatment, whereas the thickness of HUVECs in static conditions is about 9 µm, indicating that the applied flow, and the consequent cell alignment, lead to cell thinning. Regarding the thickness of the glycocalyx layer, it depends on the techniques used to measure it and usually varies from several hundred nanometres to 1 µm [53], thus it is much smaller than HUVEC thickness. Moreover, it has been shown that the glycocalyx layer under an applied shear stress up to 2.0 Pa is similar to that under static conditions [54]. Hence, in our condition (i.e. 2 Pa) the difference in HUVEC thickness between static and flow is not due to glycocalyx thickness.

To sum up, neuraminidase treatment leads to decrease of WGA signal due to removal of sialic acids, but does not substantially change HUVEC thickness due to the limited thickness of sialic acids. Instead, HUVEC thickness is markedly decreased under flow due to cell alignment and flattening. The flow chamber was first characterized by using the syringe pump to flow HRBCs both in bare and endothelialized microchannels. As expected, HRBC velocity profiles as a function of channel height showed a parabolic trend and centreline velocity was higher in bare channels as compared to that in HUVEC lined channels due to the endothelial reduction of channel lumen (more details are available in electronic supplementary material S5).

3.2. Neuraminidase treatment affects the flow behaviour of HRBCs and PfRBCs near wall

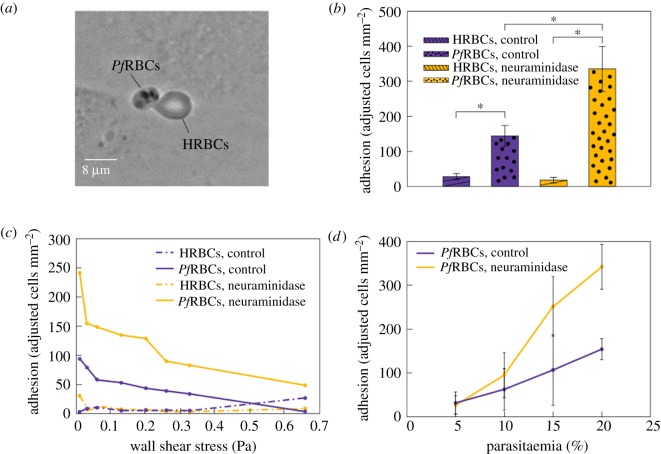

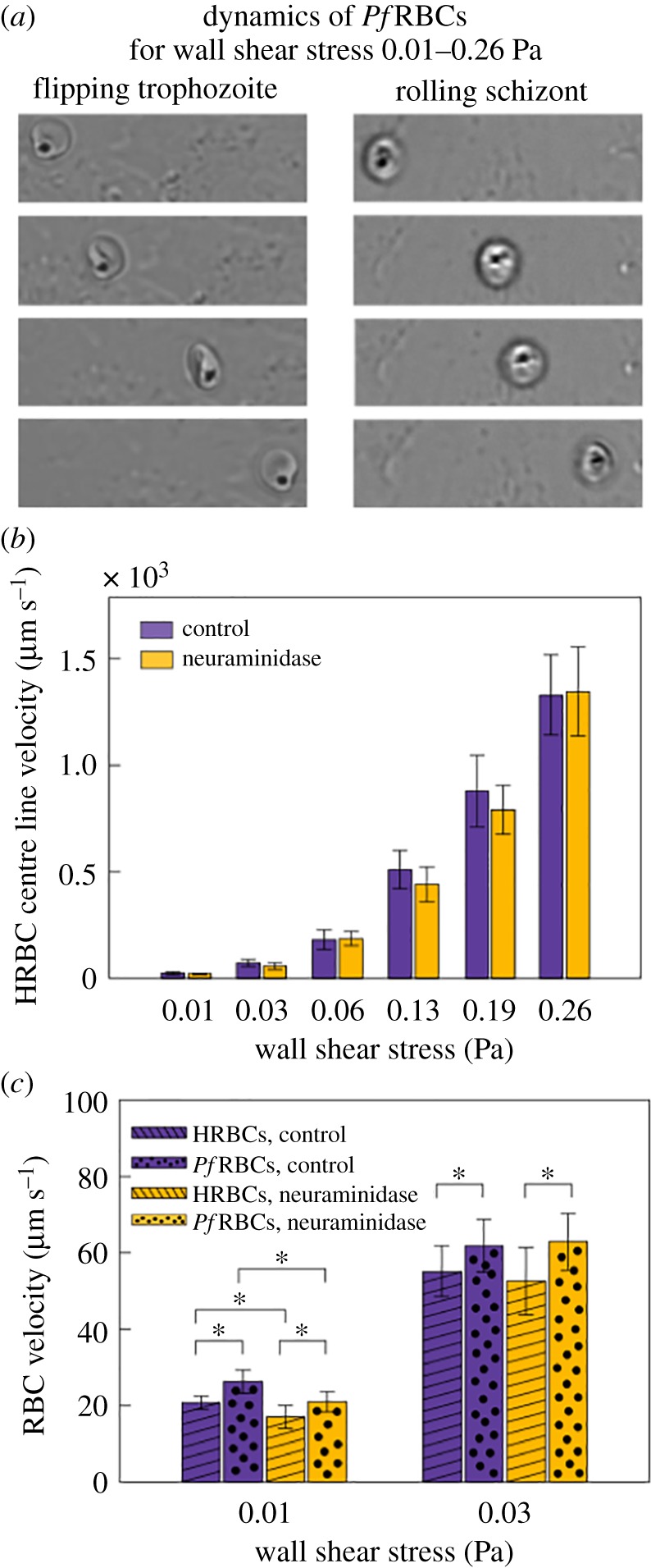

Having assessed that a physiologically relevant layer of glycocalyx-expressing HUVECs and well-controlled HRBC velocity profiles were obtained by the microfluidic set-up developed in this work, we now focus on the effect of neuraminidase on the flow behaviour of HRBCs and PfRBCs. In figure 3a representative images of PfRBCs flowing over the HUVEC monolayer are shown.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of PfRBCs flowing on a HUVEC monolayer. (a) Sequence of snapshots of a trophozoite and a schizont in their characteristic flipping and rolling motion, respectively. Their motion is maintained for all the considered wall shear stresses. (b) HRBC centre line velocity at physiological wall shear stresses for both control and neuraminidase-treated samples, showing that glycocalyx does not influence HRBC centre line velocity at a fixed channel height. (c) HRBC and PfRBC velocity on HUVEC focal plane at two representative wall shear stress values for both control and neuraminidase-treated HUVECs. PfRBC velocity is always higher than that of HRBCs (p < 0.05). A statistically significant difference is present separately between control and neuraminidase-treated samples for HRBCs and PfRBCs only at 0.01 Pa (p < 0.05): neuraminidase-treated samples are 10–14% slower compared to the control. SD obtained by following 20 HRBCs and 20 PfRBCs flowing on HUVECs for at least 10 frames in three different fields of view.

Late stage PfRBCs such as trophozoites and schizonts can be recognized by the black spot of haemozoin, a product formed from the digestion of haemoglobin by the parasites. PfRBCs at trophozoite stage showed a peculiar flipping motion and at schizont stage a rolling motion before adhering firmly to the endothelium (figure 4a). While the HRBCs move along the HUVEC surface in different motions such as tank-treading, tumbling, and rolling, depending on the flow rate (as described in electronic supplementary material, figure S1), PfRBCs only flip and roll, respectively, for all the wall shear stresses. Both behaviours have been reported in the literature for PfRBCs flowing in microchannels in vitro, coated either with adhesion molecules or with endothelial cells (e.g. see review by Rowe et al. [55]). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study of rolling and firm adhesion of PfRBCs onto endothelial cells with a defective glycocalyx has been conducted so far. We have found that the flipping and rolling dynamics is unchanged when the sialic acid layer on HUVEC glycocalyx is removed, but PfRBC motion slows down by 10–14% at 0.01 Pa.

Figure 4.

The effect of HRBC and PfRBC adhesion on HUVEC glycocalyx, before and after the removal of glycocalyx sialic acids with neuraminidase. (a) Snapshot of HRBCs and PfRBCs adhering to HUVEC layer after washing out unattached cells. (b) PfRBC adhesion efficiency is double in neuraminidase-treated endothelium with respect to the control (p < 0.001). PfRBCs always adhere significantly more than HRBCs for control and neuraminidase-treated samples (p < 0.001), while the sialic acid removal of HUVEC glycocalyx has no impact of HRBC adherence. Adjusted adhesion indicates the number of RBCs per mm2 attached to HUVECs normalized by the ratio of PfRBCs and HRBCs. (c) PfRBC adhesion efficiency decreases for increasing wall shear stresses for both control and neuraminidase-treated samples, while HRBC adhesion efficiency remains almost constant for both these conditions. RBCs were classed as adhered to the endothelium when they remained completely attached for about 500 frames for every value of shear stress. (d) Linear increase of PfRBC adhesion as function of parasitaemia for both control and neuraminidase-treated samples. SD from 10 different fields of view per value of parasitaemia.

The effect of neuraminidase on HRBC bulk flow was evaluated by comparing HRBC centre line velocity for untreated and enzyme-treated HUVECs, as shown in figure 3b. No significant difference between control and neuraminidase-treated samples is observed for each wall shear stress, i.e. the loss of sialic acids does not influence HRBC bulk flow behaviour.

This result is not unexpected due to the small thickness of the glycocalyx layer (in the range 0.17–3.02 µm) [56] with respect to the channel height (400 µm) in our microfluidic device, although a significant reduction in glycocalyx thickness has been found upon treatment with neuraminidase [47]. As no bulk flow effects were found, the attention was focused on the near wall flow behaviour of HRBCs and PfRBCs in proximity of the endothelial surface.

The same analysis has been carried out for PfRBCs before and after the removal of glycocalyx sialic acid by neuraminidase, and compared with results obtained for HRBCs. We have checked that an intact glycocalyx covers all the endothelial surface, preventing the adhesion of all the healthy and most of the infected RBCs, thus favouring the flow of RBCs across the endothelium. As shown in figure 3c, the near wall velocity of PfRBCs is always higher than that of HRBCs both for control and neuraminidase-treated samples (p < 0.05). This result could be explained by the different travelling modes of HRBCs and PfRBCs: while the first show a tank-treading behaviour, the latter exhibit more tumbling/flipping behaviour due to parasite-induced cell stiffening. Furthermore, this is consistent with a slowing-down of HRBCs moving near a polymer brush mimicking the glycocalyx, which has been described in the literature [57]. A statistically significant difference is also present separately between control and neuraminidase-treated samples for HRBCs and PfRBCs, but only at 0.01 Pa (p < 0.05). Such difference of 10–14% could be attributed to a velocity reduction induced by increased adhesion with enzyme-treated HUVECs. No difference in cell velocity is reported starting from 0.03 Pa due to the increasing distance between flowing RBCs and the endothelium which leads to lower cytoadhesion at higher wall shear stress.

3.3. Neuraminidase treatment enhances cytoadhesion of PfRBCs only, in a parasitaemia and shear stress dependent manner

The effect of PfRBCs binding to glycocalyx of vascular endothelium is studied by analysing HRBC and PfRBC firm adhesion (henceforth just referred to as adhesion) on HUVECs, before and after the selective removal of sialic acids by neuraminidase. In particular, HRBC and PfRBC adhesion has been evaluated by counting the number of RBCs attached to endothelium after 1 h flow at 0.33 Pa, unattached RBCs being flushed out by applying a strong flux at 0.39 Pa of fresh culture medium for several minutes. Images are taken all along the microchannel in 10 different fields of view (a field of view is 1920 × 1200 pixels, equivalent to 554.8 × 350.4 µm). Here, adhesion is measured in terms of an ‘adjusted’ cell count per mm2, where by ‘adjusted’ we mean that the parasitaemia of the suspension was taken into account. In our condition, HRBCs and PfRBCs constitute 80% and 20% of RBC population, respectively. The number of adhered healthy and infected RBCs per mm2 has been normalized to the respective fractions within the RBC population. An example of healthy and infected RBCs firmly adherent to endothelium is presented in figure 4a. PfRBCs are completely rigid and anchored to the endothelium, while HRBCs, although remaining adhered after washing the channel with medium at high flow rate, show an elongated, droplet-like shape in the direction of the flow. In figure 4b, PfRBC adhesion efficiency is double in neuraminidase-treated endothelium with respect to the control (p < 0.001). Moreover, PfRBCs always adhere significantly more than HRBCs both for control and neuraminidase-treated samples (p < 0.001), while the removal of glycocalyx sialic acid seems to have no impact on HRBC adherence. This strengthens the hypothesis proposed by Hempel et al. [33] according to which a damaged glycocalyx allows the interaction of the parasites with the glycoproteins present in the deeper layers of the glycocalyx, thereby resulting in enhanced adhesion.

Adhesion of HRBCs and PfRBCs is reported in figure 4c as a function of wall shear stress, where RBCs have been considered as attached to the endothelium if no cell movement was observed for 500 frames for each wall shear stress value. This choice leads to a lower number of adherent cells as compared to figure 4b, where a longer time was allowed before taking the measurements, but has the advantage of enabling a consistent and less time-consuming evaluation of the effect of the applied shear stress. PfRBC adhesion efficiency decreases at increasing wall shear stresses for both control and neuraminidase-treated samples, while HRBC adhesion efficiency remains almost constant for both these conditions. Regarding the control HUVEC monolayer, PfRBC adhesion efficiency decreases to zero, while for neuraminidase-treated HUVECs the number of adhesive PfRBCs at the highest applied shear stress (0.66 Pa) is about 50, indicating that PfRBCs are so strongly bound that even this high value of shear stress is not able to detach them from endothelium. Similar decreasing behaviour is consistent with results obtained by using micropipette manipulation and flow chamber techniques [58] and has also been found with other RBC diseases: sickle red blood cells [59] and polycythaemia vera [60]. There is a sharp decrease until 0.2–0.3 Pa, then the slope is shallower [61].

In figure 4d PfRBC adhesion is reported as a function of parasitaemia ranging from 5% to 20%. A linear increase of PfRBC adhesion is found for both control and neuraminidase-treated samples, the slope being larger for treated endothelial cells, providing further support to the higher adhesion of PfRBCs on damaged glycocalyx. These results support the hypothesis that the partial damage or complete loss of glycocalyx could account for increased PfRBC adhesion in vivo and may cause blood flow problems such as hypoxia and inflammatory processes typical of SM. An increase of PfRBC adhesion as a function of parasitaemia agrees with previous studies [62–64].

4. Discussion

We investigated the effects of a damaged glycocalyx on the flow behaviour and cytoadherence of PfRBCs in an organ-on-chip model of human microcirculation. The main motivation comes from the hypothesis recently proposed in the literature [33] that microcirculation disorders, which are especially relevant in the severe stage of malaria, are essentially due to glycocalyx disruption as a consequence of the disease progress.

At a molecular level, glycocalyx can be damaged by the shedding activity of several enzymes, such as thrombin and plasmin, which are associated with coagulation and fibrinolysis, matrix metalloproteases, and other components with sheddase-like functions produced by the parasites [33,36,65]. In this scenario, adhesion molecules located in the deeper layers of the glycocalyx, such as CD36, V-CAM1, I-CAM1 [23,66], are exposed to interactions with RBCs. While HRBCs seem to adhere slightly less than the control ones (the difference being not statistically significant) after neuraminidase-treatment, PfRBCs show an enhanced cytoadherence. This is the hallmark of the sequestration process, whereby infected cells adhere to the endothelium and escape from spleen clearance, with the consequence of microvessel obstruction and proinflammatory and coagulation activity [67,68]. In turn, these effects can generate serious complications typical of SM, such as cerebral malaria and multiorgan failure. Here, we exploit the selective cleavage of sialic acids by neuraminidase to create a model system of damaged glycocalyx in human endothelial cells, previously cultured under physiological flow conditions in a microfluidic organ-on-chip device. PfRBCs flowing close to the enzyme-treated glycocalyx showed more than two-fold enhanced adhesion as compared to untreated endothelial cells. To the best of our knowledge, this result provides the first experimental evidence of the suggested role of glycocalyx disruption as the main driver of PfRBC sequestration on the vascular endothelium in microcirculation [33]. Removal of sialic acid by neuraminidase has been recently shown to induce increased endothelial permeability in rat mesenteric microvessels in vivo [47], supporting the proposed effect of glycocalyx loss on tissue swelling due to increased vascular permeability in SM [33,69].

Peculiar interactions between PfRBCs and enzyme-treated glycocalyx are also shown in the flow behaviour near the endothelial surface, where enhanced cell rolling (and corresponding lower cell velocity) is observed at low shear stresses. It should be noticed that PfRBC (and, to less extent, HRBC) rolling has been observed near the wall even in the absence of endothelial cells or of any coatings with adhesion molecules [48]. Such host independent flipping/rolling can be attributed to parasite-induced PfRBC stiffening which increases the tumbling behaviour already present in HRBCs under certain shear rate [48]. When surface adhesion sites are present, rolling is further enhanced, likely due to the presence of knobs, which are adhesive protrusions that the parasite induces on the surface of the host RBC cell, starting about 16 h after injection. Such structures contain several proteins including PfEMP-1 (Pf erythrocyte membrane protein-1), considered key in PfRBC adhesion [34,70]. Mathematical models capturing knob-induced rolling have been shown to be in qualitative agreement with experimental results of PfRBC adhesion on endothelial cells [29]. However, the glycocalyx was not taken into account in the modelling nor was documented in the endothelial cells investigated. Therefore, our work is the first report of PfRBC dynamics on both an intact and a damaged endothelial glycocalyx.

5. Conclusion

The main result of this work is that glycocalyx loss by selective cleavage of sialic acids enhances PfRBC cytoadherence to endothelial cells in an organ-on-chip model of microcirculation. We also found that glycocalyx loss is associated with altered near wall flow behaviour, such as enhanced PfRBC rolling on the diminished endothelial monolayer. This supports the proposed vicious circle acting in SM: PfRBC cytoadherence to endothelial cells leads to glycocalyx disruption, thereby resulting in enhanced sequestration and microcirculation disorders. Hence, more evidence is provided to considering glycocalyx as a possible therapeutic target for malaria treatment, in addition to other antiadhesion adjunctive therapy [55]. Future perspectives in this area include the study of the effects of the putative sheddase molecules at plasma-level concentrations on glycocalyx impairment.

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

All data supporting this study are provided as electronic supplementary material accompanying this paper.

Authors' contributions

A.C. and V.I. contributed to all aspects of the work, carried out experiments and data analysis. G.T. and S.G. designed the experiments and wrote the paper, P.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (Programma per il finanziamento della ricerca di Ateneo, DR 341-8 Febbraio 2016) (G.T.), EPSRC and Sackler for studentship (V.I.), EPSRC EP/R011443/1 (P.C.).

References

- 1.Suresh S, Spatz J, Mills JP, Micoulet A, Dao M, Lim CT, Beil M, Seufferlein T. 2005. Connections between single-cell biomechanics and human disease states: gastrointestinal cancer and malaria. Acta Biomater. 1, 15–30. ( 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dondorp AM, Kager PA, Vreeken J, White NJ. 2000. Abnormal blood flow and red blood cell deformability in severe malaria. Parasitol. Today 16, 228–232. ( 10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01666-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. 2002. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature 415, 673–679. ( 10.1038/415673a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt S, et al. 2015. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207–211. ( 10.1038/nature15535) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crick AJ, Theron M, Tiffert T, Lew VL, Cicuta P, Rayner JC. 2014. Quantitation of malaria parasite-erythrocyte cell-cell interactions using optical tweezers. Biophys. J. 107, 846–853. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crick AJ, Tiffert T, Shah SM, Kotar J, Lew VL, Cicuta P. 2013. An automated live imaging platform for studying merozoite egress-invasion in malaria cultures. Biophys. J. 104, 997–1005. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosseini SM, Feng JJ. 2012. How malaria parasites reduce the deformability of infected red blood cells. Biophys. J. 103, 1–10. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller LH, Ackerman HC, Su X-Z, Wellems TE. 2013. Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: insights for new treatments. Nat. Med. 19, 156 ( 10.1038/nm.3073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honrado C, Fernandes M, Ciuffreda L, Spencer D, Cartwright RL, Morgan H. 2018. Dielectric characterization of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells using microfluidic impedance cytometry. J. R. Soc. Interface15, 20180416. ( 10.1098/rsif.2018.0416) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park Y, Silva DM, Popescu G, Lykotrafitis G, Choi W, Feld MS, Suresh S. 2008. Refractive index maps and membrane dynamics of human red blood cells parasitized by Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 13 730–13 735. ( 10.1073/pnas.0806100105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diez-Silva M, Dao M, Han J, Lim C-T, Suresh S. 2010. Shape and biomechanical characteristics of human red blood cells in health and disease. MRS Bull. 35, 382–388. ( 10.1557/mrs2010.571) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomaiuolo G, Lanotte L, D'Apolito R, Cassinese A, Guido S. 2016. Microconfined flow behavior of red blood cells. Med. Eng. Phys. 38, 11–16. ( 10.1016/j.medengphy.2015.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomaiuolo G, Barra M, Preziosi V, Cassinese A, Rotoli B, Guido S. 2011. Microfluidics analysis of red blood cell membrane viscoelasticity. Lab Chip 11, 449–454. ( 10.1039/C0LC00348D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herricks T, Antia M, Rathod PK. 2009. Deformability limits of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 1340–1353. ( 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01334.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaul D, Roth EJ, Nagel R, Howard R, Handunnetti S. 1991. Rosetting of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells with uninfected red blood cells enhances microvascular obstruction under flow conditions. Blood 78, 812–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig AG, Khairul M, Patil PR. 2012 Cytoadherence and severe malaria. Malays. J. Med. Sci.19, 5–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engwerda CR, Beattie L, Amante FH. 2005. The importance of the spleen in malaria. Trends Parasitol. 21, 75–80. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dondorp A, Nyanoti M, Kager P, Mithwani S, Vreeken J, Marsh K. 2002. The role of reduced red cell deformability in the pathogenesis of severe falciparum malaria and its restoration by blood transfusion. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96, 282–286. ( 10.1016/S0035-9203(02)90100-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armah H, Wiredu EK, Dodoo AK, Adjei AA, Tettey Y, Gyasi R. 2005. Cytokines and adhesion molecules expression in the brain in human cerebral malaria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2, 123–131. ( 10.3390/ijerph2005010123) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochola LB, et al. 2011. Specific receptor usage in Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence is associated with disease outcome. PLoS ONE 6, e14741 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0014741) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conroy AL, Phiri H, Hawkes M, Glover S, Mallewa M, Seydel KB, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME, Kain KC. 2010. Endothelium-based biomarkers are associated with cerebral malaria in Malawian children: a retrospective case-control study. PLoS ONE 5, e15291 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0015291) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakravorty SJ, Hughes KR, Craig AG. 2008. Host response to cytoadherence in Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. Soc. Trans.36, 221–228. ( 10.1042/BST0360221) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antia M, Herricks T, Rathod PK. 2007. Microfluidic modeling of cell–cell interactions in malaria pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 3, e99 ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030099) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooke BM, Berendt AR, Craig AG, MacGregor J, Newbold CI, Nash GB. 1994. Rolling and stationary cytoadhesion of red blood cells parasitized by Plasmodium falciparum: separate roles for ICAM-1, CD36 and thrombospondin. Br. J. Haematol. 87, 162–170. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04887.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udomsangpetch R, Reinhardt PH, Schollaardt T, Elliott JF, Kubes P, Ho M. 1997. Promiscuity of clinical Plasmodium falciparum isolates for multiple adhesion molecules under flow conditions. J. Immunol. 158, 4358–4364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho M, Schollaardt T, Niu X, Looareesuwan S, Patel KD, Kubes P. 1998. Characterization of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocyte and P-selectin interaction under flow conditions. Blood 91, 4803–4809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEver RP, Zhu C. 2010. Rolling cell adhesion. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 363–396. ( 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113238) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helms G, Dasanna AK, Schwarz US, Lanzer M. 2016. Modeling cytoadhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes and leukocytes—common principles and distinctive features. FEBS Lett. 590, 1955–1971. ( 10.1002/1873-3468.12142) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dasanna AK, Lansche C, Lanzer M, Schwarz US. 2017. Rolling adhesion of schizont stage malaria-infected red blood cells in shear flow. Biophys. J. 112, 1908–1919. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fedosov D, Caswell B, Suresh S, Karniadakis G. 2011. Quantifying the biophysical characteristics of Plasmodium-falciparum-parasitized red blood cells in microcirculation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 35–39. ( 10.1073/pnas.1009492108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedosov DA, Lei H, Caswell B, Suresh S, Karniadakis GE. 2011. Multiscale modeling of red blood cell mechanics and blood flow in malaria. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002270 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fedosov DA, Caswell B, Karniadakis GE. 2011. Wall shear stress-based model for adhesive dynamics of red blood cells in malaria. Biophys. J. 100, 2084–2093. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hempel C, Pasini EM, Kurtzhals JA. 2016. Endothelial glycocalyx: shedding light on malaria pathogenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 453–457. ( 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogt AM, Barragan A, Chen Q, Kironde F, Spillmann D, Wahlgren M. 2003. Heparan sulfate on endothelial cells mediates the binding of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes via the DBL1α domain of PfEMP1. Blood 101, 2405–2411. ( 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogerson SJ, Chaiyaroj SC, Ng K, Reeder JC, Brown GV. 1995. Chondroitin sulfate A is a cell surface receptor for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. J. Exp. Med. 182, 15–20. ( 10.1084/jem.182.1.15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietmann A, Helbok R, Lackner P, Issifou S, Lell B, Matsiegui P-B, Reindl M, Schmutzhard E, Kremsner PG. 2008. Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in Plasmodium falciparum malaria: serum levels of TIMP-1 are associated with disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 1614–1620. ( 10.1086/587943) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barker AL, Konopatskaya O, Neal CR, Macpherson JV, Whatmore JL, Winlove CP, Unwin PR, Shore AC. 2004. Observation and characterisation of the glycocalyx of viable human endothelial cells using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 1006–1011. ( 10.1039/B312189E) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsvirkun D, Grichine A, Duperray A, Misbah C, Bureau L. 2017. Microvasculature on a chip: study of the endothelial surface layer and the flow structure of red blood cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 45036 ( 10.1038/srep45036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts DJ, Berendt AR, Pinches R, Nash G, Marsh K, Newbold CI. 1992. Rapid switching to multiple antigenic and adhesive phenotypes in malaria. Nature 357, 689 ( 10.1038/357689a0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trager W, Jensen JB. 1976. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science 193, 673–675. ( 10.1126/science.781840) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esposito A, Choimet J-B, Skepper JN, Mauritz JM, Lew VL, Kaminski CF, Tiffert T. 2010. Quantitative imaging of human red blood cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Biophys. J. 99, 953–960. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.065) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. 1979. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J. Parasitol. 65, 418–420. ( 10.2307/3280287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radfar A, Méndez D, Moneriz C, Linares M, Marín-García P, Puyet A, Diez A, Bautista JM. 2009. Synchronous culture of Plasmodium falciparum at high parasitemia levels. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1899 ( 10.1038/nprot.2009.198) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papaioannou TG, Stefanadis C. 2005. Vascular wall shear stress: basic principles and methods. Hellenic J. Cardiol. 46, 9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cassidy JT, Jourdian GW, Roseman S. 1965. The sialic acids VI. Purification and properties of sialidase from Clostridium perfringens. J. Biol. Chem. 240, 3501–3506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pahakis MY, Kosky JR, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. 2007. The role of endothelial glycocalyx components in mechanotransduction of fluid shear stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355, 228–233. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.137) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Betteridge KB, Arkill KP, Neal CR, Harper SJ, Foster RR, Satchell SC, Bates DO, Salmon AH. 2017. Sialic acids regulate microvessel permeability, revealed by novel in vivo studies of endothelial glycocalyx structure and function. J. Physiol. 595, 5015–5035. ( 10.1113/JP274167) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy S, Dharmadhikari J, Dharmadhikari A, Mathur D, Sharma S. 2005 Plasmodium-infected red blood cells exhibit enhanced rolling independent of host cells and alter flow of uninfected red cells. Curr. Sci.89, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vartanian KB, Kirkpatrick SJ, Hanson SR, Hinds MT. 2008. Endothelial cell cytoskeletal alignment independent of fluid shear stress on micropatterned surfaces. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 371, 787–792. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.167) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malek AM, Izumo S. 1996. Mechanism of endothelial cell shape change and cytoskeletal remodeling in response to fluid shear stress. J. Cell Sci. 109, 713–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kataoka H, Ushiyama A, Kawakami H, Akimoto Y, Matsubara S, Iijima T. 2016. Fluorescent imaging of endothelial glycocalyx layer with wheat germ agglutinin using intravital microscopy. Microsc. Res. Tech. 79, 31–37. ( 10.1002/jemt.22602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bai K, Wang W. 2012. Spatio-temporal development of the endothelial glycocalyx layer and its mechanical property in vitro. J. R. Soc. Interface9, 2290–2298. ( 10.1098/rsif.2011.0901) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu W, Wang X, Bai K, Lin M, Sukhorukov G, Wang W. 2014. Microcapsules functionalized with neuraminidase can enter vascular endothelial cells in vitro. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20141027 ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.1027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ueda A, Shimomura M, Ikeda M, Yamaguchi R, Tanishita K. 2004. Effect of glycocalyx on shear-dependent albumin uptake in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H2287–H2294. ( 10.1152/ajpheart.00808.2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowe JA, Claessens A, Corrigan RA, Arman M. 2009. Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to human cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med.11, e16. ( 10.1017/S1462399409001082) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kolářová H, Ambrůzová B, Švihálková Šindlerová L, Klinke A, Kubala L. 2014. Modulation of endothelial glycocalyx structure under inflammatory conditions. Mediators Inflamm.2014, 694312. ( 10.1055/2014/694312) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lanotte L, Tomaiuolo G, Misbah C, Bureau L, Guido S. 2014. Red blood cell dynamics in polymer brush-coated microcapillaries: a model of endothelial glycocalyx in vitro. Biomicrofluidics 8, 014104 ( 10.1063/1.4863723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nash G, Cooke B, Marsh K, Berendt A, Newbold C, Stuart J. 1992. Rheological analysis of the adhesive interactions of red blood cells parasitized by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood 79, 798–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walmet PS, Eckman JR, Wick TM. 2003. Inflammatory mediators promote strong sickle cell adherence to endothelium under venular flow conditions. Am. J. Hematol. 73, 215–224. ( 10.1002/ajh.10360) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wautier M-P, El Nemer W, Gane P, Rain J-D, Cartron J-P, Colin Y, Le Van Kim C, Wautier J-L. 2007. Increased adhesion to endothelial cells of erythrocytes from patients with polycythemia vera is mediated by laminin 5 chain and Lu/BCAM. Blood 110, 894–901. ( 10.1182/blood-2006-10-048298) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yipp BG, Anand S, Schollaardt T, Patel KD, Looareesuwan S, Ho M. 2000. Synergism of multiple adhesion molecules in mediating cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to microvascular endothelial cells under flow. Blood 96, 2292–2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooke B, Morris-Jones S, Greenwood B, Nash G. 1993. Adhesion of parasitized red blood cells to cultured endothelial cells: a flow-based study of isolates from Gambian children with falciparum malaria. Parasitology 107, 359–368. ( 10.1017/S0031182000067706) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Viebig NK, Wulbrand U, Förster R, Andrews KT, Lanzer M, Knolle PA. 2005. Direct activation of human endothelial cells by Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 73, 3271–3277. ( 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3271-3277.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCormick CJ, Craig A, Roberts D, Newbold CI, Berendt AR. 1997. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and CD36 synergize to mediate adherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to cultured human microvascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2521–2529. ( 10.1172/JCI119794) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Becker BF, Jacob M, Leipert S, Salmon AH, Chappell D. 2015. Degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx in clinical settings: searching for the sheddases. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 80, 389–402. ( 10.1111/bcp.12629) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho M, Hickey MJ, Murray AG, Andonegui G, Kubes P. 2000. Visualization of Plasmodium falciparum–endothelium interactions in human microvasculature. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1205–1212. ( 10.1084/jem.192.8.1205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Francischetti IM. 2008. Does activation of the blood coagulation cascade have a role in malaria pathogenesis? Trends Parasitol. 24, 258–263. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2008.03.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Francischetti IM, et al. 2007. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes induce tissue factor expression in endothelial cells and support the assembly of multimolecular coagulation complexes. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 155–165. ( 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02232.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seydel KB, et al. 2015. Brain swelling and death in children with cerebral malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1126–1137. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa1400116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacPherson G, Warrell M, White N, Looareesuwan S, Warrell D. 1985 Human cerebral malaria. A quantitative ultrastructural analysis of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration. Am. J. Pathol.119, 385–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study are provided as electronic supplementary material accompanying this paper.