Abstract

Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy is a rare phenomenon and there is limited literature on its management. Cushing’s disease in pregnancy is even less common and there is little guidance to help in the treatment for this patient group. Diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy is often delayed due to overlap of symptoms. In addition, there are no validated diagnostic tests or parameters documented.

We present a case of a 30-year-old woman presenting to the antenatal clinic at 13 weeks of pregnancy with high suspicion of Cushing’s disease. Her 21-week fetal scan showed a congenital diaphragmatic hernia and she underwent pituitary magnetic resonance imaging, which confirm Cushing’s disease. She successfully underwent transsphenoidal adenomectomy with histology confirming a corticotroph adenoma. Tests following transsphenoidal surgery confirmed remission of Cushing’s disease and she underwent an emergency caesarean section at 38 weeks. Unfortunately, her baby died from complications associated with the congenital abnormality 36 hours after birth.

The patient remains in remission following delivery. To date, there have been no reported cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with Cushing’s disease in pregnancy. In addition, we believe that this is only the eighth reported patient to have undergone successful transsphenoidal surgery for Cushing’s disease in pregnancy.

Keywords: Skull base, Transsphenoidal surgery, Endoscopic surgery, Cushing’s disease

Introduction

Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy is exceptionally rare and raises a number of treatment dilemmas. Not only is there significant maternal morbidity, the state of hypercortisolism in pregnancy has adverse implications for fetal health. Infertility in Cushing’s syndrome is associated with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism secondary to cortisol and/or to androgen excess.1,2 To date, approximately 200 cases of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy have been reported.3,4 Of these, 40–50% had adrenal adenoma, 30% had Cushing’s disease and 10% had either adrenal carcinoma, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)-independent hyperplasia or ectopic ACTH secretion.5 Diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy is difficult and is often delayed due to an overlap between symptomatology and the physiological effects of pregnancy such as hypertension, hyperglycaemia, weight gain, striae and mood changes. In addition, hormonal analysis and imaging modalities have their restrictions in pregnancy. During normal pregnancy there is a physiological upregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis resulting in elevated levels of cortisol and ACTH, making it even more difficult to diagnose Cushing’s syndrome.6 As there is increased morbidity for both mother and fetus, early diagnosis and management is essential. Close to 50 cases of Cushing’s disease in pregnancy have been reported to date, with only 12 of these cases being treated with transsphenoidal surgery during pregnancy. We present a case of recurrent Cushing’s disease in pregnancy successfully treated with endoscopic transsphenoidal resection. To our knowledge, this is the first ever case reported of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy complicated by fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia and the eighth reported case successfully treated with transsphenoidal surgery.7

Case history

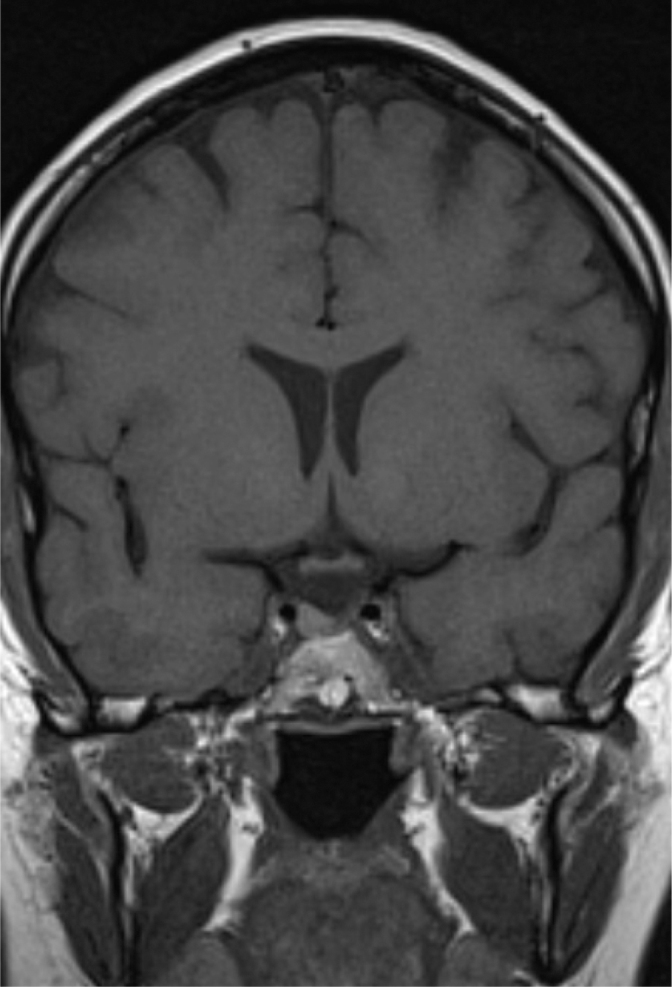

We describe a case of a 30-year-old woman who presented to her local antenatal clinic in the first trimester of her pregnancy. She had recently been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and was adequately managed with metformin. Her past medical history included Cushing’s disease secondary to a pituitary microadenoma for which she had undergone transsphenoidal adenomectomy six years previously. Following this procedure, she saw clinical resolution of her symptoms and restoration of her menstruation. Unfortunately, in her postoperative period she was lost to follow-up. Given her complex past medical history and recent onset diabetes, she was referred to a specialist endocrine team in a nearby tertiary care unit at 13 weeks of gestation. She was kept under close antenatal surveillance with a high clinical suspicion of Cushing’s disease. Subsequently, a 21-week fetal ultrasound scan revealed a congenital diaphragmatic hernia, the contents of which included stomach, bowel and liver. At this point the obstetric team offered the patient a termination, given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with such an anomaly, but this was refused. Following repeat non-contrast pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), discussion at the pituitary endocrine multidisciplinary team meeting concluded a likely recurrence of a right-sided pituitary microadenoma measuring 4.5 mm (Fig 1). Considering the risks of hypercortisolism for both the mother and fetus, transsphenoidal adenomectomy was recommended and the patient successfully underwent the procedure in the 23rd week of gestation. Transsphenoidal surgery was undertaken with the patient lying supine with a slight left lateral tilt to reduce aortocaval compression and with 30-degree head up to reduce venous bleeding and improve the surgical field. The left lateral tilt turned the head further away from surgical reach and the head was turned further to the right to compensate. Cocaine nasal decongestion was avoided and 1:10,000 adrenaline used instead.

Figure 1.

Non-contrast magnetic resonance image showing right-sided pituitary lesion.

The fetal heart rate was monitored before surgery and immediately following surgery while the patient was in the recovery suite. The surgery itself was uneventful and was undertaken with the obstetric team monitoring for any fetal distress. Histopathology confirmed recurrent corticotroph adenoma and postoperatively she was put on hydrocortisone. Her diabetes was well controlled with metformin. At 33 weeks she was found to be hypertensive and was put on labetalol and nifedipine. At 38 weeks, she had an emergency caesarean section, but the baby died 36 hours later secondary to complications of the congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Assessment of cortisol status a few weeks after delivery, confirmed disease remission with a morning serum cortisol of 34 nmol/l and a short Synacthen® test of 71 nmol/l (t = 0) and 164 nmol/l (t = 30 minutes) after one year showing continued suppression of the HPA axis. She remains on 30 mg split of hydrocortisone.

Discussion

Women with Cushing’s syndrome present with symptoms of amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea in 75% of cases. In such patients, pregnancy is rare, owing to a pathophysiological state of hyperandrogenism and hypercortisolism suppressing gonadotrophin secretion.1,2,8,9,10 It has previously been observed that benign adrenal adenomas were the most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy, in contrast to non-pregnant women where pituitary pathology is the most common cause.11

The rarity of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy has resulted in a low index of suspicion among physicians, which unfortunately can lead to late diagnosis and serious maternal and fetal complications.11 Part of the delay in diagnosis is attributed to the overlap in clinical presentation with some of the features of Cushing’s syndrome being similar to those in normal pregnancy; these include weight gain, hypertension, abdominal striae. The syndrome can also easily be confused with complications of pregnancy such as gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Interestingly, Cushing’s syndrome can be discriminated from normal pregnancy by violaceous striae as opposed to skin coloured, easy bruising and symptoms of elevated androgens, such as acne and hirsutism.11

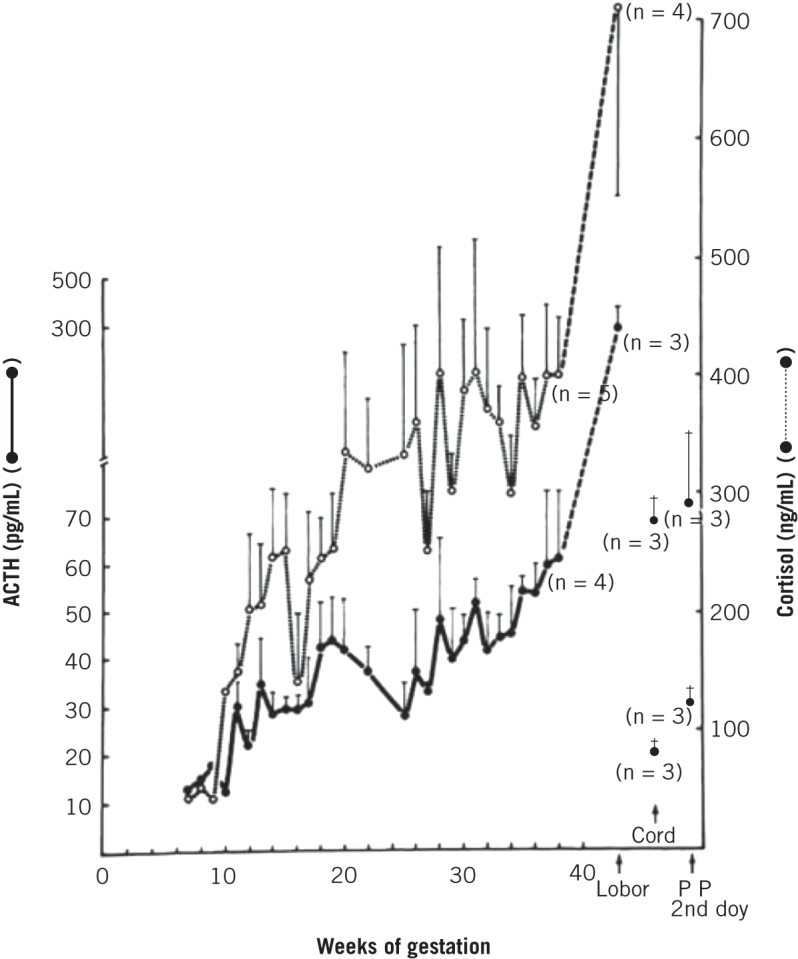

During a state of normal pregnancy, we see a physiological upregulation of the HPA axis (Fig 2). There is progressive increase in serum ACTH, cortisol and urinary free cortisol levels throughout pregnancy, which further complicates the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy.2,6,8 To date, no definitive biochemical parameters have been published to help diagnose Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy. Increased levels of cortisol-binding globulin stimulate production of cortisol, increasing circulating bound cortisol. Both total and free cortisol levels rise throughout pregnancy with levels being two to three times higher compared with non-pregnant women and similar to those found in Cushing’s syndrome. This in turn results in rising urinary free cortisol levels throughout gestation again reaching up to three times the upper limit of normal.6 These changes are driven by a rise in ACTH which reaches a maximum level during labour and delivery, where levels can be three-fold higher than normal.6 The cause for these elevated levels of ACTH include placental synthesis and release of ACTH and corticotrophin-releasing hormone, pituitary desensitisation to cortisol feedback or enhanced pituitary response to corticotrophin-releasing hormone.6 In addition to these physiological changes, cortisol suppression by dexamethasone may be blunted; but circadian rhythm of cortisol and ACTH is preserved.11 This can be a useful aid in diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy as urinary free cortisol and serum cortisol levels cannot be always used as diagnostic parameters. Lindsay et al proposed that values of urinary free cortisol in the second and third trimester above three times the upper limit of normal should be considered a strong clinical indicator of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy as are midnight salivary cortisol levels two to three times above normal.6,14 A high-dose (8 mg) dexamethasone suppression test may serve useful in identifying pituitary or adrenal aetiology. Strictly speaking, adrenal pathology will not suppress cortisol whereas classical Cushing’s disease will; however, owing to the physiological changes of the HPA axis in pregnancy, this test is less reliable. Not all cases of Cushing’s disease in pregnancy will completely suppress cortisol, but of the cases where it has been used, almost all cases have been correctly identified by 50% cortisol suppression threshold.6,7 Ultrasound imaging is a safe and quick procedure to identify adrenal masses in patients with clinical and biochemical suspicion of Cushing’s syndrome. Typically, in Cushing’s syndrome secondary to an adrenal adenoma, one can expect to find elevated urinary free cortisol with suppression of ACTH and loss of circadian rhythm. In cases of suspected Cushing’s disease, the use of MRI has not been proven to be safe in the first trimester because of the potential effects on organogenesis and it is therefore generally avoided.15 There have been many reported cases of the use of non-contrast MRI (as in our case), mainly in the second and third trimester, with no adverse effects observed and this is generally the safest period to do so.7,16 Gadolinium contrast is characterised by the US Food and Drug Administration as category C and be avoided in pregnancy due to potential teratogenicity. It is important to note, however, that non-contrast enhanced MRI may not be very informative for microadenomas and the physiological enlargement of the pituitary gland during pregnancy may mask a small tumour.

Figure 2.

Serial increases in serum cortisol and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) during pregnancy in normal controls (reproduced with permission from: Carr BP, Parker CR Jr, Madden JD et al. Maternal plasma adrenocorticotrophin and cortisol relationships throughout human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981; 139: 416–422.)

Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy has adverse health implication on both the mother and fetus. Most commonly occurring maternal complications include hypertension (68%), gestational diabetes (25%), pre-eclampsia (14%), higher incidence of abortion and premature labour, cardiac failure (3%) and maternal death (2%).1 The most common fetal morbidity is prematurity (43%) followed by intrauterine growth restriction (21%), stillbirth (6%), intrauterine death (5%) and other congenital abnormalities.3 These risks persist even among women treated during pregnancy, although early treatment improves both maternal and fetal outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this case was the first reported with a fetal complication of a diaphragmatic hernia. The contents of the hernia sac included the stomach, bowel and liver. This abnormality carries a high risk of pulmonary hypoplasia and has an approximately 40% mortality rate.17 In view of significant morbidity, Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy is considered an obstetric high-risk condition and requires close surveillance and early effective treatment.

Management of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy can be also very challenging due to the associated added risk to mother and child. Surgery is considered as the more favourable treatment option, with reported livebirth rates up to 87% following transsphenoidal adenomectomy or adrenalectomy.9,10,18,19 After an extensive literature review, to the best of our knowledge this is the eighth case of Cushing’s disease successfully treated in pregnancy (Table 1).3,7,18–24 In all cases of pituitary adenoma successfully treated with transsphenoidal surgery, the procedure was performed between the end of the first trimester and the early second trimester, a period associated with lower maternal and fetal complications.7 Adrenalectomies have been successful performed during a similar gestation time with resolution of hypercortisolism and high birth rates.25 Medical therapy has been used in 20 reported cases to date. The most common steroidogenesis inhibitors were metyrapone (61%), ketoconazole (15%) and cyproheptadine (11%) used in the second and third trimesters. Metyrapone has shown successful control with no teratogenicity but carries a risk of severe hypertension and pre-eclampsia.3 Other medication has less commonly been used due to possible risk of teratogenicity, proven on animal studies only.26,27 Despite this, ketoconazole has successfully been used in a small number of cases of Cushing’s syndrome without any adverse consequences.27,28

Table 1.

A literature review of all reported cases of Cushing’s disease treated with transsphenoidal adenomectomy in pregnancy.

| Reference | Timing of TSA (weeks of gestation) | Postoperative complications | Delivery | Postoperative Outcome |

| Casson et al (1987)19 | 22 | Pre-eclampsia | C-section 30 weeks; baby required ventilation but survived | n/a |

| Pickard et al (1990)22 | 16 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Coyne et al (1992)20 | 14 | Uneventful | NVD 38 weeks; healthy baby | Cortisol normal; unsure residual disease |

| Pinette et al (1994)23 | 16 | Uneventful | 33 weeks fetal death, tight nuchal cord | Elevated UFC, persistent CD |

| Ross et al (1995)18 | 16 | Uneventful | Fetal distress and C-section 37 weeks; healthy baby | Remission |

| Mellor et al (1998)21 | (2nd trimester) | Uneventful | C-section at 33 weeks; healthy baby | UFC normal Remission |

| Verdugo et al (2004)24 | 23 | Uneventful | NVD 39 weeks; healthy baby | Remission |

| Lindsay et al (2005)6 | 18 | Pre-eclampsia | 34 weeks induced; healthy baby | Remission |

| 14 | Transient SIADH | 33 weeks IU death, tight nuchal cord | Persistent CD | |

| 10 | Uneventful | NVD at term; healthy baby | Remission | |

| 17 | Transient SIADH and hypertension | C-section 24 weeks for reversal cord flow; baby died | Remission | |

| Abbassy et al (2015) | 18 | Diabetes insipidus | NVD 39 weeks; healthy baby | Remission |

| Jolly et al (2016) | 23 | Uneventful | C-section 38 weeks; fetal death due to congenital diaphragmatic hernia after 36 hours | Remission |

CD, Cushing’s disease; IU, intrauterine; NVD, normal vaginal delivery; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion; TSA, transsphenoidal adenomectomy; UFC, urinary free cortisol.

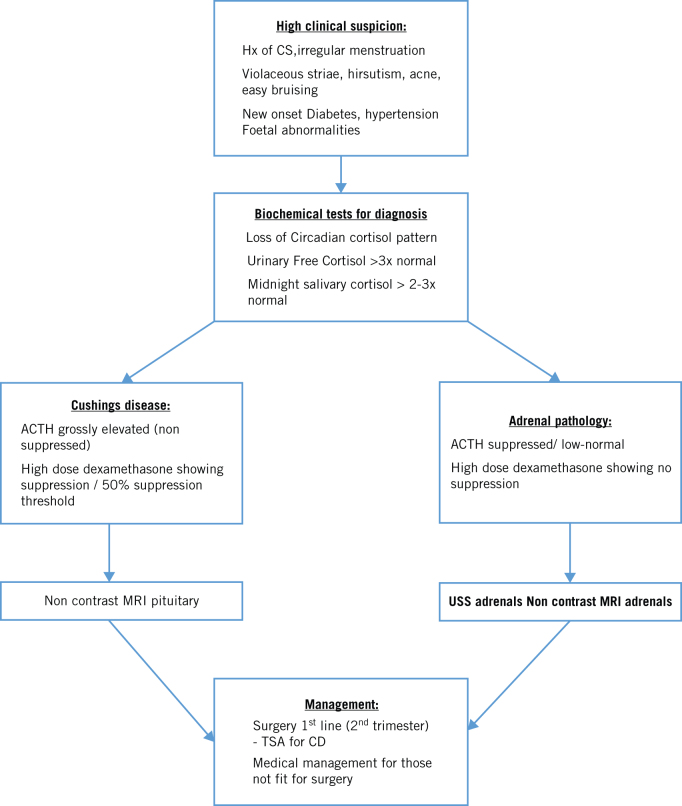

Owing to the rarity of this condition, there appear to be no guidelines with regards to diagnosis and management of Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy. A high index of clinical suspicion can aid swift diagnosis and early treatment, reducing maternal and fetal morbidity and improving pregnancy outcomes. High clinical suspicion of Cushing’s should be based on past medical history, symptoms of violaceous striae, easy bruising and symptoms of elevated androgens, such as acne and hirsutism. If suspected, all patients should go on to have biochemical analysis looking for urinary free cortisol over three times the upper limit of normal, midnight salivary cortisol two to three times above the upper limit of normal and loss of circadian rhythms. Imaging modalities such as ultrasound or MRI can help with the diagnosis. Surgery seems to be the preferred fist-line treatment, with limited medical therapies available for those not fit for surgery. The best time period for treatment appears to be in the second trimester, where successful outcomes have been reported. In Figure 3, we outline a recommended treatment algorithm based on an up-to-date review of the literature to help guide clinicians to manage Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy.

Figure 3.

An algorithm to diagnose and manage Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy.

References

- 1.Gopal RA, Acharya SV, Bandgar TR et al. Cushing disease with pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol 2012; : 533–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bronstein MD, Machado MC, Fragoso MCBV. Management of pregnant patients with Cushing’s syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 2015; : R85–R91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsay JR, Jonklaas J, Oldfield EH, Nieman LK. . Cushing’s syndrome during pregnancy: personal experience and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; : 3,077–3,083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kita M, Sakalidou M, Saratzis A. Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy: report of a case and review of the literature. Hormones (Athens) 2007; : 242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lekarev O, New MI. Adrenal disease in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; : 959–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsay JR, Nieman LK. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in pregnancy: challenges in disease detection and treatment. Endocr Rev 2005; : 755–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbassy M, Kshettry V, Hamrahian A, Recinos P. Surgical management of recurrent Cushing’s disease in pregnancy: a case report. Surg Neurol Int 2015; : S640–S645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheeler LR. Cushing’s syndrome and pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1994; : 619–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aron DC, Schnall AM, Sheeler LR. Cushing’s syndrome and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990; : 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buescher MA, McClamrock HD, Adashi EY. Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1992; : 130–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami S, Saitoh M, Kubo T et al. A case of mid-trimester intrauterine fetal death with Cushing’s Syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; : 153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nassi R, Ladu C, Vezzosi C, Mannelli M. Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol 2015; : 102–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magiakou MA, Mastorakos G, Rabin D. The maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in the third trimester of human pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996; : 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopes LM, Francisco RP, Galletta MA, Bronstein MD. Determination of nighttime salivary cortisol during pregnancy: comparison with values in non-pregnancy and Cushing’s disease. Pituitary 2016; (1): 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson SK, Goldman SM, Shah KB et al. Acute non-traumatic maternal illnesses in pregnancy: imaging approaches. Emerg Radiol 2005; : 199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown MA, Birchard KR, Semelka RC. Magnetic resonance evaluation of pregnant patients with acute abdominal pain. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2005; : 206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller RL, Tacy TA, Xu J et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: endothelin-1, pulmonary hypertension, and disease severity. AMJ Respir Crit Care Med 2010; : 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross RJ, Chew SL, Perry L et al. Diagnosis and selective cure of Cushing’s disease during pregnancy by transsphenoidal surgery. Eur J Endocrinol 1995; : 722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casson IF, Davis JC, Jeffreys RV et al. Successful management of Cushing’ disease during pregnancy by transsphenoidal adenectomy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1987; : 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coyne TJ, Atkinson RL, Prins JB. Adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting pituitary tumor associated with pregnancy: case report. Neurosurgery 1992; : 953–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellor A, Harvey RD, Pobereskin LH, Sneyd JR. Cushing’s disease treated by trans-sphenoidal selective adenomectomy in mid-pregnancy. Br J Anaesth 1998; : 850–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickard J, Jochen AL, Sadur CN, Hofeldt FD. Cushing’s syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1990; : 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinette MG, Pan YQ, Oppenheim D et al. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus corticotropin sampling with corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation in a pregnant patient with Cushing's syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; : 563–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verdugo C, Alegría J, Grant C et al. Cushing’s disease treatment with transsphenoidal surgery during pregnancy. Rev Med Chil 2004; : 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabezon C, Bruno OD, Cohen M et al. Twin pregnancy in a patient with Cushing’s disease. Fertil Steril 1999; : 371–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanco C, Maqueda E, Rubio JA, Rodriguez A. Cushing’s syndrome during pregnancy secondary to adrenal adenoma: metyrapone treatment and laparoscopic adrenalectomy. J Endocrinol Invest 2006; : 164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boronat M, Marrero D, Lopez-Plasencia Y et al. Successful outcome of pregnancy in a patient with Cushing’s disease under treatment with ketoconazole during the first trimester of gestation. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011; : 675–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costenaro F, Rodrigues TC, de Lima PB et al. A successful case of Cushings disease pregnancy treated with ketoconazole. Gynecol Endocrinol 2015; : 176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]