Abstract

Coral reefs are increasingly threatened by thermal bleaching and tropical storm events associated with rising sea surface temperatures. Deeper habitats offer some protection from these impacts and may safeguard reef-coral biodiversity, but their faunas are largely undescribed for the Indo-Pacific. Here, we show high species richness of scleractinian corals in mesophotic habitats (30–125 m) for the northern Great Barrier Reef region that greatly exceeds previous records for mesophotic habitats globally. Overall, 45% of shallow-reef species (less than or equal to 30 m), 78% of genera, and all families extended below 30 m depth, with 13% of species, 41% of genera, and 78% of families extending below 45 m. Maximum depth of occurrence showed a weak relationship to phylogeny, but a strong correlation with maximum latitudinal extent. Species recorded in the mesophotic had a significantly greater than expected probability of also occurring in shaded microhabitats and at higher latitudes, consistent with light as a common limiting factor. The findings suggest an important role for deeper habitats, particularly depths 30–45 m, in preserving evolutionary lineages of Indo-Pacific corals. Deeper reef areas are clearly more diverse than previously acknowledged and therefore deserve full consideration in our efforts to protect the world's coral reef biodiversity.

Keywords: scleractinia, deep reef, refuge, phylogeny, faunal overlap

1. Introduction

Coral reefs around the world are severely threatened by the increasing frequency and magnitude of climate-related stressors, such as mass bleaching events and tropical storms [1–3]. In particular, the 2015/2016 mass coral bleaching event was the most severe on record, with reefs across the Indo-Pacific severely affected and up to 90% coral mortality reported in the northern Great Barrier Reef and adjacent Coral Sea atolls of Australia [2]. These impacts are so severe that local extinctions and slow recovery are likely in many areas [3,4]. Both thermal bleaching and severe tropical storms are widely predicted to increase in frequency and severity as global sea temperatures increase [2,5], thus there is an urgent need to investigate areas that may safeguard biodiversity during such events.

Deeper reef areas have received much recent interest for their potential to provide refuge against major disturbances [6–8]. While not immune from disturbance [8,9], they offer a degree of protection to deeper coral communities as impacts of thermal bleaching and severe tropical storms often decline over depth [9–11]. Surviving deep coral populations might therefore mitigate against local extinctions and supply larval recruits to facilitate recovery of shallow populations on damaged reefs [10–12]. These potential roles are the subject of much recent debate [6–8], but one role that has been largely overlooked is that of lineage protection. The preservation of evolutionary lineages is increasingly recognized in conservation biology and is particularly relevant to reef corals because many are considered endangered [13–15]. Reef corals have recently undergone major taxonomic and phylogenetic revision [16], but are generally accepted as having two major modern lineages, the ‘Robust’ and ‘Complex’ clades [17], each with multiple families, that arose from a deep-sea lineage up to 425 Myr ago [17,18]. The extent to which these phylogenetically distant lineages are able to extend into deeper habitats is therefore of interest to both the conservation and general biology of reef corals.

Despite the potentially critical roles that deeper habitats may play in the future of reefs and reef corals, species-level assessments and their overlap with shallow communities have been largely limited to the Red Sea and west Atlantic, with little taxonomic data for the extensive reef areas of the Indo-Pacific [19]. Deeper coral habitats are commonly defined as the mesophotic zone, encompassing depths 30 to approximately 150 m [20] and prior to this study, the greatest richness was reported for the Red Sea (93 species) and in the west Atlantic for Jamaica (38 species, table 1). The Great Barrier Reef region (GBR) has extensive areas of potential mesophotic habitat [23], but studies have been largely limited to observation by submersibles and sampling by dredge with few taxonomic collections [24–30]. Only 32 valid species were reported for the GBR mesophotic zone prior to our research programme (table 1).

Table 1.

Previous reports for species richness of scleractinian corals in mesophotic habitats (depth 30 to approx. 150 m). Total valid species [21] according to current nomenclature [22], literature sources are detailed in the electronic supplementary material, table S1.

| region | mesophotic species | total species | proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Seaa | 93a | 310 | 30.9 |

| Maldives | 34 | 292 | 8.7 |

| Great Barrier Reef | 32 | 421b | 7.6 |

| New Caledonia | 72 | 438 | 16.6 |

| Japan | 17 | 418 | 4.1 |

| Micronesia | 71 | 431 | 16.5 |

| Austral Is., Polynesia | 62 | 153 | 43.8 |

| Northeast Pacifica | 23a | 77 | 29.9 |

| Honduras/Belizea | 29a | 60 | 48.3 |

| Jamaicaa | 38a | 59 | 64.4 |

aRelatively well documented.

bSix new records from our study not included.

Here, we report the main findings of a large taxonomic study of mesophotic corals of the northern GBR and adjacent Coral Sea atolls (herein referred to as northern GBR region), conducted from 2010 to 2016. Samples collected using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and deep self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) diving were used for the great majority of records as there are issues with in situ identification of many coral genera [26,31], particularly in mesophotic habitats where morphologies can be atypical [32,33]. We build on initial reports from our research programme that focused specifically on staghorn corals [33] and lower mesophotic depths (60–126 m) [34] and consolidate data from museum collections and previous literature to summarize the fauna and its potential for safeguarding shallow-reef taxa and evolutionary lineages. We also test for a phylogenetic pattern to depth distributions and compare the mesophotic fauna to other marginal faunas to further the understanding of factors limiting reef-coral distributions.

2. Methods

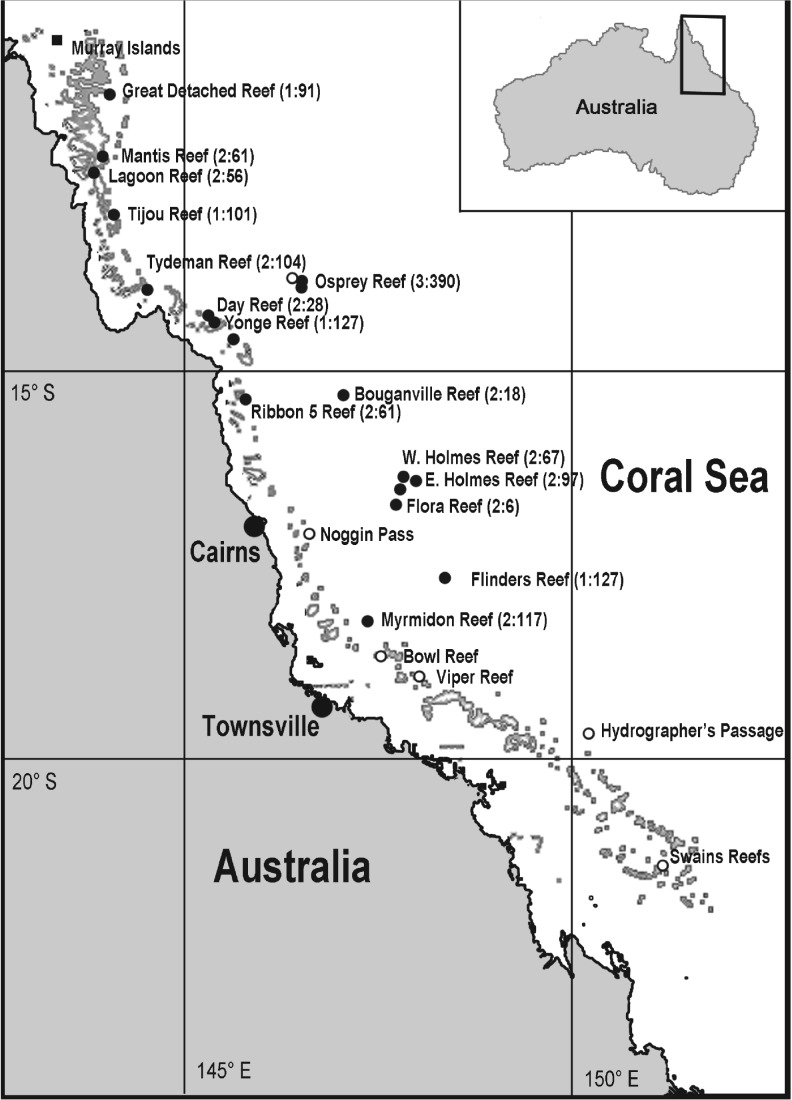

Seven dedicated mesophotic expeditions were conducted from 2010 to 2016 (figure 1), the majority as part of the ‘XL Catlin Seaview Survey’ (http://catlinseaviewsurvey.com). Twenty-seven sites were assessed (figure 1), many with steep bathymetric profiles so that both SCUBA and ROV operations could be conducted from an anchored vessel. The numerous technical and safety issues associated with working on deep and often exposed sites resulted in wide variation in sampling effort, but for each site 500–1500 m2 was surveyed by divers at 40 m depth and 2000–6000 m2 by ROV (Seabotix vLBV300 or LBV200) from depths 41 m to below the extent of coral occurrence. An area 500–3000 m2 at 5–10 m depth was also surveyed by divers for species detected in the mesophotic. As the morphology of deeper specimens was often atypical (consistent with reports [19,32]) and many required microscopic examination for accurate identification, we mainly used specimen-based records. Small (3–15 cm long) samples of coral colonies were taken by divers using a hammer and chisel or by ROV using a grab. The ROVs allowed far longer surveys than SCUBA, but the grabs were relatively slow and provided fewer specimens. Macro photographs (DSLR Olympus E410 with a 14–54 mm lens) or for the ROVs, higher-resolution video (1980 × 1024 px), were used to document in situ morphology and for corals that were difficult to sample.

Figure 1.

Locations with sites: number of specimens collected used in this study (filled circles), from unpublished museum records (squares), and previous studies [24–30] (open circles).

Samples were processed in bleach solution (4% hypochlorite, 36–72 h), rinsed in freshwater, dried, and registered into the Queensland Museum Collection (QMC) and the Invertebrate Zoology collection at the California Academy of Sciences. Specimens were examined by a microscope (Wild M5) and identified by comparison with type material, specimens from published works in the QMC, and according to the wider taxonomic literature. Additional specimens were sourced from the QMC which includes shallow-reef collections (e.g. [26,31]) and mesophotic material from the region. Nomenclature was according to the World Register of Marine Species [22]. Because of the need to use mainly specimen-based records and issues with variable sampling between sites, quantitative analyses between sites was not feasible.

Phylogenetic analyses were based upon the median tree of Huang & Roy [35] for species occurring in the region [21] according to current nomenclature [22]. To test for a phylogenetic effect in maximum depth of occurrence, we used Blomberg's K statistic and Pagel's λ [36] executed in the package Phytools [37] in R. Additional depth data for shallow-reef species not detected in this study were from [38].

Similarities between the mesophotic coral fauna and those documented for shaded [39] and high latitude [38] habitats were tested using Pearson's and Mantel–Haenszel χ2 (VCD package [40]), analysing the number of shared species, with expected values from 3-way contingency tables. Analyses with and without the genus Acropora were conducted as this genus has a specialized deep-water fauna restricted to low latitudes [41]. An additional test was used to compare high latitude and mesophotic faunas including the genus Montipora which was not present in the main analyses due to a lack of data for shaded habitats. The correlation between maximum depth of occurrence and maximum latitude was analysed with Kendall's τ statistic [42] implemented in R. A non-parametric method was used as these data showed strong deviations from a normal distribution.

3. Results

For the northern GBR region, we identified 169 species and 57 genera of scleractinian corals from 1263 specimens collected between 30 and 125 m depth (electronic supplementary material, table S2). A further four species and one genus were recorded from QMC specimens not previously reported and 11 species and one genus from in situ macro photographs (electronic supplementary material, table S2 and figure S3). Three species were tentatively recorded as ‘cf.’, but were not included in totals or analyses. Species richness decreased rapidly with depth: we found 38 species from 24 genera for more than or equal to 60 m depth and four species from four genera for more than or equal to 100 m, although fewer specimens (177) were collected deeper than 40 m depth. Overall, 75 species were detected on only one to two occasions below 30 m depth. Only six species (Zoopilus echinatus, Craterastrea levis, and four Acropora species) were recorded exclusively below 30 m depth. Overall, 109 species were recorded at depths exceeding previously reported global maxima documented in [24–30,38]. Zoopilus echinatus and one tentative identification (Lithophyllon cf. spinifer) were new records for the region (electronic supplementary material, tables S2, S3 and figure S1). Four other species (Acropora tenella, Acropora pichoni, Acropora kimbeensis, and Craterastrea levis) were also new records, but reported previously by our group [33,34].

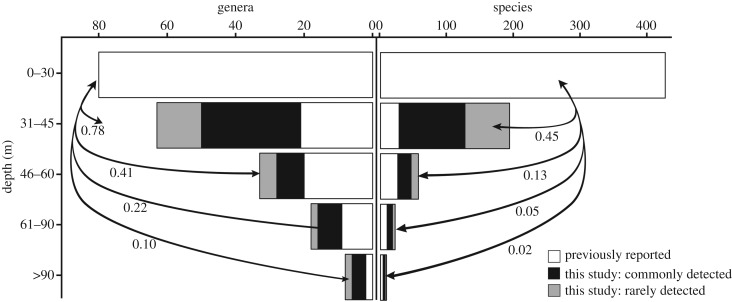

Combined with the 11 species and three additional genera previously reported for the mesophotic in the region [24–30], but not detected in our study, we show substantial overlap between the mesophotic and shallow habitats (less than 30 m; figure 2). Excluding taxa that are apparently restricted to the mesophotic in the region, 45% of species and 78% of genera reported for shallow habitats [21,22] extended deeper than 30 m depth. These proportions declined to 13% and 41% greater than 45 m and 2% and 10% greater than 90 m depth (species/genera, respectively). Eight genera reported for the region are only recorded for shallow (less than 30 m) habitats (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Summary of reef-coral taxa detected at depth and the proportional overlap with shallow-reef fauna [21] for the northern GBR region. According to current nomenclature [22], species detected exclusively in the mesophotic were excluded, ‘this study’ includes preliminary records reported previously by our group [33,34]. Previously reported [24–30], see electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2 for details.

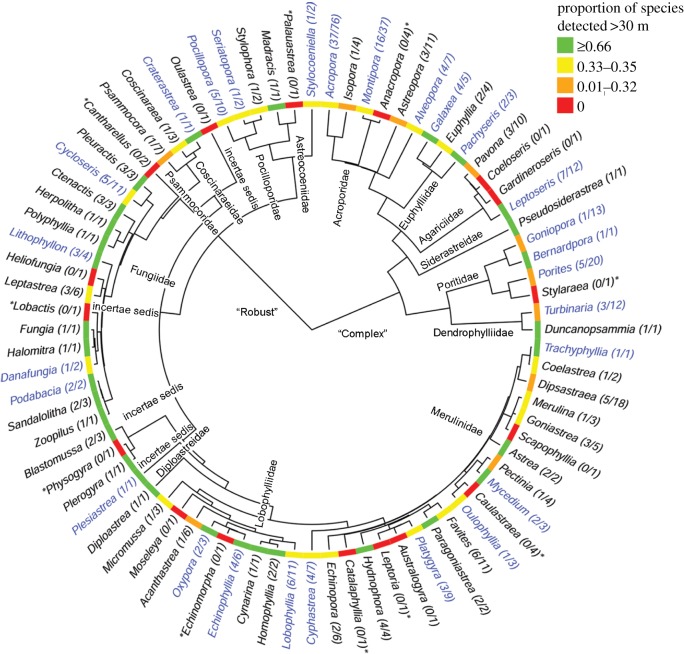

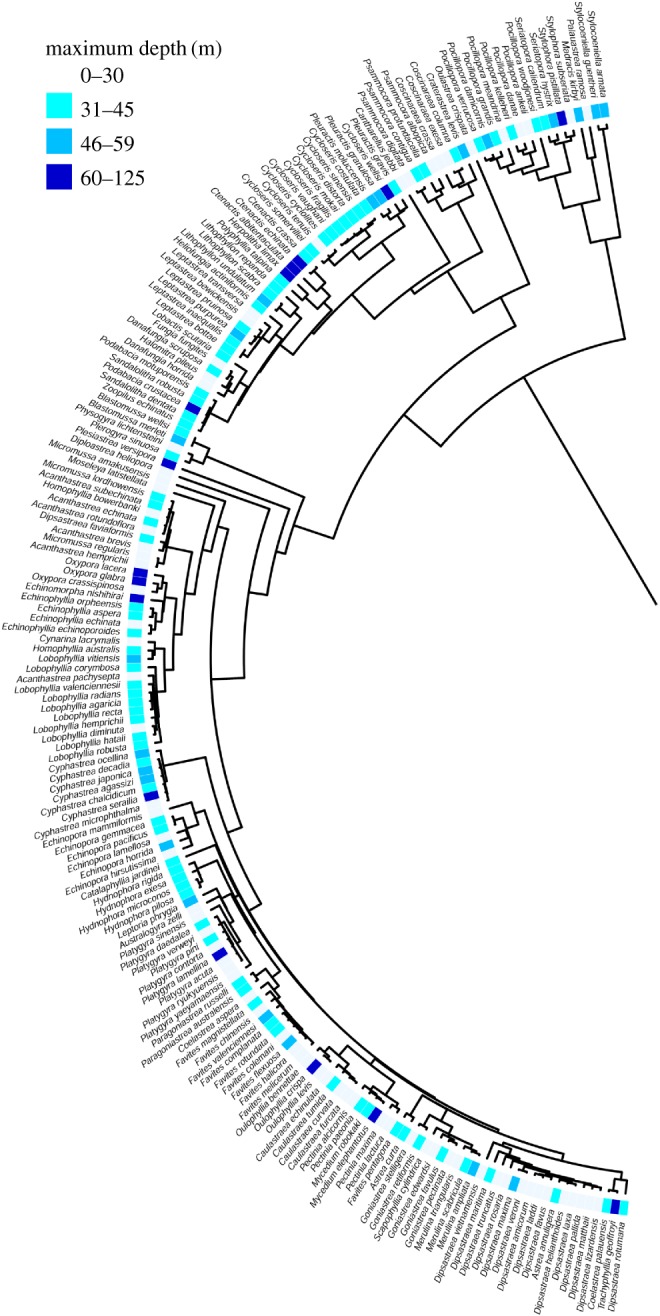

Figure 3.

Each family of scleractinian reef corals and a wide range of genera occurred deeper than 30 m depth, with many extending to 60 m or deeper (in blue font). Tree is based upon the median tree of [35] and is shown for species documented for the northern GBR region [21] according to current nomenclature [22]. Number of species for genus in brackets, *reported greater than 30 m depth for other geographic regions. (Online version in colour.)

Phylogenetic analyses showed each of the 14 families documented for the region were represented in the mesophotic zone and 64% of these in the lower mesophotic (more than or equal to 60 m, figure 3). Few genera showed a high proportion of deep-occurring species and these were phylogenetically distant: Leptoseris and Galaxea in the Complex clade and Oxypora, Ctenactis, Pleuractis, and Echinophyllia in the Robust clade (figure 3). Maximum depth of occurrence showed only a low to moderate phylogenetic signal (K = 0.006, λ = 0.780), with the capacity to extend to deeper depths varying within most genera and present across the scleractinian supertree (figure 4). This analysis showed some additional clades within the large genera Acropora and Montipora restricted to shallow depths (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Figure 4.

The ability to extend to depth varied widely within genera and was only slightly related to phylogeny (Blomberg's K = 0.006, p = 0.137, Pagel's λ = 0.780). Here, the ‘Robust’ clade for scleractinian corals reported for the northern GBR region [21] with current nomenclature [22] is shown. The median tree of [35] is used, with additional depth data from [38]. For the complete tree, see electronic supplementary material, figure S2. (Online version in colour.)

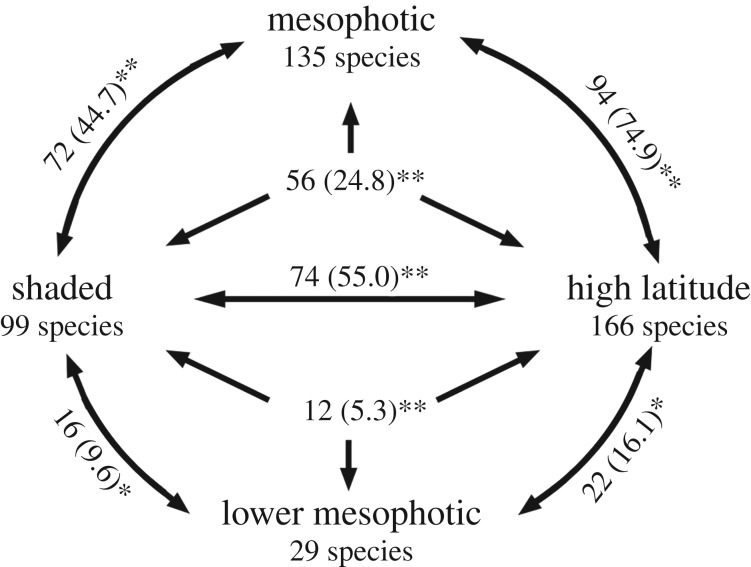

Species recorded in the mesophotic and lower mesophotic from the northern GBR region had a significantly greater than expected probability of also occurring in shaded microhabitats and at higher latitudes (figure 5). High latitude and shaded faunas also showed significant similarity to each other and the number of species occurring in all three habitats was significantly greater than expected (figure 5). Similarities between high latitude and mesophotic faunas were robust to inclusion of the genus Montipora (χ2 = 11.32, p < 0.001). Including genus Acropora reduced but maintained the significant similarities (p < 0.01), except between lower mesophotic and high latitude faunas (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). This is consistent with the highly diverse Acropora having a specialized deep-water fauna restricted to low latitudes [26,41]. Maximum depth of occurrence and maximum documented latitude were also strongly correlated (Kendall's tau z = 2.60, p = 0.009, see electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Figure 5.

Species that occurred at mesophotic (30–150 m) and lower mesophotic (60–150 m) depths in the northern GBR region were significantly more likely to extend to higher latitudes (greater than 34°) and into shaded microhabitats. Numbers indicate species shared with expected values in brackets, ** denotes p ≪ 0.01, * denotes p < 0.05 from Pearson's and Mantel–Haenszel χ2. Species for the region according to [35], shaded habitats [39] and latitudinal extent [38]. Genus Acropora excluded here, details and further analyses can be found in the electronic supplementary material table S2 and figure S3.

4. Discussion

Mesophotic depths are often regarded as marginal for reef-building scleractinian corals [43], but here we document a richness of 195 species, 62 genera, and 14 families from 30 to 125 m depth for the northern GBR region. This greatly exceeds richness reported for other regions of the world (table 1), strengthening the case that mesophotic coral ecosystems are worthy of greater consideration in overall coral reef management and ecology [8,19]. Our findings indicate that a much greater proportion of Indo-Pacific reef-coral diversity occurs at mesophotic depths than previously recognized, which has implications for deep-reef areas potentially safeguarding some coral biodiversity from climate change impacts. The mesophotic coral fauna also showed surprising similarities with other marginal reef faunas, providing further insight into the factors limiting the bathymetric and latitudinal distribution of reef corals.

The northern GBR region supports a relatively high diversity of reef-building scleractinian corals [21] and we found 45% of shallow-reef species and 78% of genera occurring at depths greater than 30 m (table 1 and figure 2). While the proportions of species and genera are similar to those reported for other well-documented regions with the exception of Jamaica (table 1), here we show overlap for a much larger fauna, representing a significant proportion of common Indo-Pacific taxa. The degree to which shallow-reef taxa extend into deep habitats is perhaps critical to the future of reefs because deeper habitats provide one of the few potential refuges for corals during certain climate change impacts. Thermal bleaching and severe storm events have severely damaged reefs across the globe and are predicted to increase in severity and frequency [2,5], but their impacts tend to decrease with depth in some regions [9–11]. Our findings show wide scope in terms of taxon diversity, for deeper habitats to provide refuge and extinction mitigation during these events. Perhaps most significantly, each family is represented in the mesophotic zone with many extending to greater depths, despite their wide phylogenetic diversity (figure 3). Thus, each lineage has some potential for being safeguarded in the event of widespread shallow-reef degradation. These findings are particularly relevant because many species of reef corals are currently considered endangered or vulnerable [15].

In addition to lineage preservation, refuged deep populations might contribute to shallow-reef recovery by providing a source of larval recruits [9,10]. Such recruitment would be particularly important in accelerating recovery after severe bleaching events, given that the rate of recovery between events is likely to be critical to the future of reefs [1,3]. However, the capacity of deep and often sparse populations to accelerate or even contribute to shallow-reef recovery is currently the subject of much debate [6–8]. Studies of genetic connectivity suggest a low potential for deep-sourced recruitment at shallow depths for some species [44] and decreased light at greater depths (40–60 m) is associated with decreased fecundity for several species [45]. Here, we detected a large proportion of species at upper mesophotic depths (figure 2), supporting the concept of an ‘optimum refuge zone’ protected from the worst bleaching and storm impacts, but not so deep that diversity, light, and genetic isolation become limiting [9,44]. Given the number and range of taxa present at both shallow and mesophotic depths, even limited recruitment from a subset of the deep fauna is likely to be critical in shallow areas where severe mortality has occurred. Clearly, the role that deep populations play following severe impacts requires further study, but we here show much greater scope in terms of systematics than previously acknowledged.

The mesophotic taxon richness we found greatly exceeds the 32 species and 20 genera previously reported for this region and that of other documented regions (table 1). This likely reflects the large sampling effort and geographical extent of the study (27 sites over approx. 150 000 km2), but also the location. This is the first detailed taxonomic report of mesophotic corals across a large reef system with high shallow-reef species richness. The northern GBR region has approximately 427 scleractinian reef corals reported (including six new records from our study), exceeding that of the other regions where mesophotic corals are relatively well documented (table 1). While the relationship between shallow- and deep-reef richness has not been fully established, these results provide some evidence that the two are interrelated, at least over regional scales.

Specific environmental conditions at our study sites are also likely to have contributed to the species richness. Overall, 109 species showed depths exceeding previously documented maxima (electronic supplementary material, table S2), including many species common across the Indo-Pacific [21,26,31]. Many of our study sites were located at relatively low latitudes (figure 1) on atolls or outer barrier reef slopes, far from terrestrial influences and bathed in waters of extremely high clarity [46]. Such conditions are optimal for light transmission to depth, a factor that influences the bathymetric distribution of many reef corals [47]. While low-latitude deep sites with high water clarity are common throughout the Indo-Pacific, this is one of the first taxonomic studies for such habitats. Low temperatures also limit species occurrence for some mesophotic habitats [32], but for several of our deep sites the annual minima [48] were well above those considered limiting for reef corals [47]. The region studied was extremely remote, relatively pristine, well-protected by marine parks, and the fieldwork was conducted prior to the 2016 thermal bleaching event: thus it provides an important baseline for deep-reef assemblages and the depth distributions of many reef-coral species.

The significant similarities shown between coral faunas from mesophotic, high latitude, and shaded habitats (figure 5) provide an indication of the factors limiting species occurrence in these marginal habitats. Similarities between mesophotic and shaded faunas are not surprising because light is generally accepted as one of the main limits to species occurrence for these habitats [39,49]. However, the significant similarity between both these faunas and higher latitude fauna is a novel finding. The results indicate that species able to tolerate low levels of light were also more likely to extend to deeper depths and higher latitudes. Light availability has long been hypothesized to limit the latitudinal distribution of reef formation and corals [46,50], and recent studies have provided some quantitative evidence for this [41,51]. It is critical to understand the extent to which light is constraining current limits of coral distributions because this will likely determine their scope for latitudinal extension in response to warming oceans. Clearly, the response of individual species to lowered light regimes needs to be assessed, but our results provide further evidence that light limitation plays an important role in the current bathymetric and latitudinal distribution of reef corals.

The outlook for coral reefs is currently grim given recent bleaching and severe tropical storm events [1–5]; indeed the region studied underwent high coral mortality across wide areas of shallow reef shortly after we completed our sampling programme [2]. However, our findings provide a glimmer of hope. A far greater proportion of Indo-Pacific coral taxa are present in deep-reef habitats than previously acknowledged, potentially providing extinction mitigation and lineage continuity in the face of some climate change impacts. Deep refuged populations may also contribute to shallow-reef recovery, although this role is currently debated [6–8]. We also show that a greater than expected subset of species is likely to benefit from a combination of deep-reef, high latitude [52], and shaded [11,53] refuges. Aside from their role as a potential refuge, deep habitats are clearly far more diverse and extensive than previously acknowledged and are therefore much in need of further study, management, and protection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The majority of collections were made during the ‘XL Catlin Seaview Survey’. We thank Kyra Hay, Norbert Englebert, and David Whillas for contributing to the collections and David Aguirre for statistical advice and Luke Denseley, Jaap Barendrecht, and Linda Tonka for diving and ROV support. We also thank Ed Roberts, Emre Turak, Tom Bridge, David Aguirre, Davey Kline for assistance in the field and Bert Hoeksema, Elizabeth Moodie, Barbara Done, and Hiro Fukami for some of the identifications. The crews from ‘Eye to Eye Marine Encounters', ‘Reef Connections’, and ‘Mike Ball Dive Expeditions' provided logistical support and Barbara Done and Marlene Trenerry provided laboratory assistance. We thank our reviewers for their excellent input.

Ethics

Sampling was conducted under GBRMPA and Australian Government permits and Queensland Museum guidelines. Our samples were collected under permit: GBRMPA G12/35281.1, G14/37294.1, AU-COM2012-151, AU-COM2013-226, AU-COM2016-308.

Data accessibility

Additional results and references supporting this article have been uploaded as online electronic supplementary material. Datasets used in this study are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6pn119g [54].

Authors' contributions

Specimen collection: P.M. and P.B.; identification: C.W., M.P., and P.M.; analysis: P.M.; expedition and equipment: P.B. and P.M.; preparation of manuscript: P.M., P.B., M.P., and C.W.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Catlin Group Limited, the Global Change Institute and an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) DE160101433.

References

- 1.Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. 2007. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742. (doi:101126/science1152509) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes TP, et al. 2017. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377. (doi:101038/nature21707) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes TP, et al. 2018. Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83. ( 10.1126/science.aan8048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards ZT, Day JC. 2018. Biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef—how adequately is it protected? PeerJ 6, e4747 ( 10.7717/peerj.4747) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Hooidonk R, Maynard J, Tamelander J, Gove J, Ahmadia G, Raymundo L, Williams G, Heron SF, Planes S.. 2016. Local-scale projections of coral reef futures and implications of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Sci. Rep. 6, 39666 (doi:101038/srep39666) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semmler RF, Hoot WC, Reaka ML. 2016. Are mesophotic coral ecosystems distinct communities and can they serve as refugia for shallow reefs? Coral Reefs 36, 433–444. ( 10.1007/s00338-016-1530-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner JA, Babcock RC, Hovey R, Kendrick GA. 2017. Deep thinking: a systematic review of mesophotic coral cosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 2309–2320. ( 10.1093/icesjms/fsx085) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocha LA, Pinheiro HT, Shepherd B, Papastamatiou YP, Luiz OL, Pyle RL, Bongaerts P. 2018. Mesophotic coral ecosystems are threatened and ecologically distinct from shallow water reefs. Science 361, 281–284. ( 10.1126/science.aaq1614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bongaerts P, Ridgway T, Sampayo EM. 2010. Assessing the ‘deep reef refugia’ hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs 29, 309–327. (doi:101007/s00338-009-0581-x) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glynn PW. 1996. Coral reef bleaching: facts, hypotheses and implications. Glob. Change Biol. 2, 495–509. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2486.1996.tb00063.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muir PR, Marshall PA, Abdulla A, Aguirre JD. 2017. Species identity and depth predict bleaching severity in reef building corals: shall the deep inherit the reef? Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20171551 ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.1551) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith TB, Glynn PW, Mate JL, Toth LT, Gyory J. 2014. A depth refugium from catastrophic coral bleaching prevents regional extinction. Ecology 95, 1663–1673. ( 10.1890/13-0468.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang D. 2012. Threatened reef corals of the world. PLoS ONE 7, e34459 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0034459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curnick DJ, et al. 2015. Setting evolutionary-based conservation priorities for a phylogenetically data-poor taxonomic group (Scleractinia). Anim. Conserv. 18, 303–312. ( 10.1111/acv.12185) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter KE, et al. 2008. One-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk from climate change and local impacts. Science 321, 560–563. ( 10.1126/science.1159196) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitahara MV, Fukami H, Benzoni F, Huang D. 2016. The new systematics of Scleractinia: integrating molecular and morphological evidence. In The cnidaria, past, present, and future (eds Goffredo S, Dubinski Z), pp. 41–59. Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romano SL, Cairns SD. 2000. Molecular phylogenetic hypotheses for the evolution of scleractinian corals. Bull. Mar. Sci. 67, 1043–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolarski J, Kitahara MV, Miller SJ, Cairns SD, Mazur M, Meibom A. 2011. The ancient evolutionary origins of Scleractinia revealed by azooxanthellate corals. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 1–10. ( 10.1186/1471-2148-11-316) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker EK, Puglise KA, Harris PT. 2016. Mesophotic coral ecosystems — A lifeboat for coral reefs? Nairobi: The United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loya Y, Eyal G, Treibitz T, Lesser MP, Appeldoorn R. 2016. Theme section on mesophotic coral ecosystems: advances in knowledge and future perspectives. Coral Reefs 35, 1–9. ( 10.1007/s00338-016-1410-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veron JEN, Stafford-Smith MG, Turak E, DeVantier LM.. 2016. Corals of the world. Accessed 06 May 2018. See http://www.coralsoftheworld.org/coral_geographic/interactive_map/.

- 22.Hoeksema B, Cairns S.. 2018. World list of Scleractinia. See http://www.marinespecies.org/scleractinia.

- 23.Harris PT, Bridge TCL, Beaman RJ. 2013. Submerged banks in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, greatly increase available coral reef habitat. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 70, 284–293. ( 10.1093/icesjms/fss165) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells JW. 1985. Notes on Indo-Pacific scleractinian corals II. A new species of Acropora from Australia. Pacific Sci. 39, 338–339. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarano F, Pichon M. 1988. Morphology and ecology of the deep fore reef slope at Osprey Reef (Coral Sea). In Proc. 6th Int. Coral reef Symp (eds Choat H, et al.), pp. 607–611. Townsville, Australia: ICRS. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace CC. 1999. Staghorn corals of the world. Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopley D. 2006. Coral reef growth on the shelf margin of the Great Barrier Reef with special reference to the Pompey complex. J. Coastal Res. 22, 150–158. ( 10.2112/05A-0012.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CSIRO 2016. Seabed Biodiversity Study 2003-2006 Records accessed in Atlas of living Australia. See www.ala.org.

- 29.Bridge TCL, Fabricius KE, Bongaerts P, Wallace CC, Muir PR. 2012. Diversity of Scleractinia and Octocorallia in the mesophotic zone of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs 31, 179–189. ( 10.1007/s00338-011-0828-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoeksema BW. 2015. Latitudinal species diversity gradient of mushroom corals off eastern Australia: a baseline from the 1970s. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 165, 190–198. ( 10.1016/j.ecss.2015.05.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veron JEN, Pichon M. 1976. Scleractinia of eastern Australia part 1, families Thamnasteriidae, Astrocoeniidae, Pocilloporidae. Canberra: Australian Institute of Marine Science. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahng SE, García-Sais JR, Spalding HL, Brokovich E, Wagner D, Weil E, Hinderstein L, Toonen RJ. 2010. Community ecology of mesophotic coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs 29, 255–275. ( 10.1007/s00338-010-0593-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muir P, Wallace C, Bridge TCL, Bongaerts P. 2015. Diverse staghorn coral fauna on the mesophotic reefs of north-east Australia. PLoS ONE 10, e0117933 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0117933) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Englebert N, Bongaerts P, Muir P, Hay K, Pichon M, Hoegh-Guldberg O. 2017. Lower mesophotic coral communities (60-125 m depth) of the northern Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea. PLoS ONE 12, e0170336 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0170336) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang D, Roy K. 2016. The future of evolutionary diversity in reef corals. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140010 ( 10.1098/rstb.2014.0010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blomberg SP, Garland T Jr, Ives AR. 2003. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: behavioural traits are more labile. Evolution 57, 717–745. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00285.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revell LJ. 2012. Phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 217–223. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madin J, et al. 2018. Coral traits database. See www.coraltriats.org/ctdb_20180210.zip.

- 39.Dinesen ZD. 1983. Shade-dwelling corals of the Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 10, 173–185. ( 10.3354/meps010173) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer D, Zeileis A, Hornik K. 2017. VCD: Visualizing Categorical Data. R package version 1.4–4.

- 41.Muir PR, Wallace CC, Done T, Aguirre JD. 2015. Limited scope for latitudinal extension of reef corals. Science 348, 1135–1138. (doi:101126/science1259911) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kendall M. 1938. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 30, 81–89. ( 10.1093/biomet/30.1-2.81) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Camp EF, Schoepf V, Mumby PJ, Hardtke LA, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Smith DJ, Suggett DJ. 2018. The future of coral reefs subject to rapid climate change: lessons from natural extreme environments. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, 4 ( 10.3389/fmars.2018.00004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bongaerts P, Riginos C, Brunner R, Englebert N, Smith SR, Hoegh-Guldberg O. 2017. Deep reefs are not universal refuges: reseeding potential varies among coral species . Sci. Adv. 3, e1602373 ( 10.1126/sciadv.1602373) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shlesinger T, Grinblat M, Rapuano H, Amit T, Loya Y. 2017. Can mesophotic reefs replenish shallow reefs? Reduced coral reproductive performance casts a doubt. Ecology 99, 421–437. ( 10.1002/ecy.2098) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brodie J, De'ath G, Devlin M, Furnas M, Wright M. 2007. Spatial and temporal patterns of near-surface chlorophyll a in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Mar. Freshwater Res. 58, 342–353. ( 10.1071/MF06236) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Done TJ. 2011. Corals: environmental controls on growth. In Encylopedia of modern coral reefs (ed. Hopley D.), pp. 281–293. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frade PR, Bongaerts P, Englebert N, Rogers A, Gonzalez-Rivero M, Hoegh-Guldberg O. 2018. Deep reefs of the Great Barrier Reef offer limited thermal refuge during mass coral bleaching. Nat. Comm. 9, 3447 ( 10.1038/s41467-018-05741-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dinesen ZD. 1982. Regional variation in shade-dwelling coral assemblages of the Great Barrier Reef province. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 7, 117–123. ( 10.3354/meps007117) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleypas JA, McManus JW, Meñez LAB. 1999. Environmental limits to coral reef development: where do we draw the line? Am. Zool. 39, 146–159. ( 10.1093/icb/39.1.146) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sommer B, Sampayo EM, Beger M, Harrison PL, Babcock RC, Pandolfi JM. 2017. Local and regional controls of phylogenetic structure at the high-latitude range limits of corals. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170915 ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0915) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beger M, Sommer B, Harrison PL, Smith SD, Pandolfi JM. 2014. Conserving potential coral reef refuges at high latitudes. Divers. Distrib. 20, 245–257. ( 10.1111/ddi.12140) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coelho VR, Fenner D, Caruso C, Bayles BR, Huang Y, Birkeland C. 2017. Shading as a mitigation tool for coral bleaching in three common Indo-Pacific species. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 497, 152–163. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2017.09.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muir PR, Wallace CC, Pichon M, Bongaerts P. 2018. Data from: High species richness and lineage diversity of reef corals in the mesophotic zone Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.6pn119g) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Muir PR, Wallace CC, Pichon M, Bongaerts P. 2018. Data from: High species richness and lineage diversity of reef corals in the mesophotic zone Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.6pn119g) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional results and references supporting this article have been uploaded as online electronic supplementary material. Datasets used in this study are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6pn119g [54].