Abstract

Background

Our previous study has shown that cadmium (Cd) exposure is not only a risk factor for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), but also correlated with the clinical stage and lymph node metastasis. However, the underlying molecular events of Cd involved in NPC progression remain to be elucidated.

Purpose

The objective of this study was to decipher how Cd impacts the malignant phenotypes of NPC cells.

Methods

NPC cell lines CNE-1 and CNE-2 were continuously exposed with 1 μM Cd chloride for 10 weeks, designating as chronic Cd treated NPC cells (CCT-NPC). MTT assay, colony formation assay and xenograft tumor growth were used to assess cell viability in vitro and in vivo. Transwell assays were performed to detect cell invasion and migration. The protein levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin as well as β-catenin and casein kinase 1α(CK1α) were measured by Western blot. Immunofluorescence staining was used to observe the distribution of filament actin (F-actin), β-catenin and CK1α. The mRNA levels of downstream target genes of β-catenin were detected by RT-PCR. Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity was assessed by TOPFlash/FOPFlash dual luciferase report system. MS-PCR was used to detect the methylation status of CK1α. Finally, the activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway and cell biological properties were examined following treatment of CCT-NPC cells with 5-aza-2-deoxy-cytidine(5-aza-CdR).

Results

CCT-NPC cells showed an increase in cell proliferation, colony formation, invasion and migration compared to the parental cells. Cd also induced cytoskeleton reorganization and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Upregulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin and increased luciferase activity accompanied with transcription of downstream target genes were found in CCT-NPC cells. Treatment of CCT-CNE1 cells with 5-aza-CdR could reverse the hypermethylation of CK1α and attenuate the cell malignancy.

Conclusion

These results support a role for chronic Cd exposure as a driving force for the malignant progression of NPC via epigenetic activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Keywords: cadmium, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Wnt/β-catenin, DNA methylation, casein kinase 1α

Introduction

Cd, a ubiquitous carcinogenic pollutant, has long been recognized as a toxic metal. Occupational inhalation, cigarette smoke, food and drinking water, or ambient air are the primary routes to Cd exposure.1 Cd has a very long biological half-life ranging from 15 to 40 years, and is retained in the liver and kidneys. In 1993, Cd and its inorganic compounds were classified as Group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer for causing lung cancer.2,3

Occupational Cd exposure has been associated with elevated risk for lung and prostate cancers.3,4 Nevertheless, enhanced cancer risk may not be restricted to comparatively high occupational exposure.5 For the general population, daily exposures are under low level conditions. Numerous data from cohort or cross-sectional studies have shown that environmentally relevant dietary exposure to Cd contributes to the development of cancer of the prostate, lung, genitourinary, breast, endometrium, pancreas, urinary bladder and colon cancers, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma.6–11 Furthermore, a putative carcinogenic role of Cd has been validated by in vitro and in vivo models.11–17

NPC is a unique malignancy that arises from the epithelium of the nasopharynx with a high prevalence in east and Southeast Asia, especially in the Guangdong and Guangxi provinces in southern China.18 The unique ethnic and geographical distribution of NPC indicates its unusual etiology. Three major etiologic factors, genetic susceptibility, Epstein–Barr virus infection and environmental factors, have been identified as being involved in NPC pathogenesis, alone or in synergy.18,19 It has been acknowledged that environmental exposures serve as a driving force in tumor development and progression.20 But to date, only nitrosamine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nickel are regarded as environmental risk factors in the development and progression of NPC.18 Recent epidemiological data from Khlifi et al and our laboratory suggested a correlation between NPC and blood levels of Cd in Tunisian and Chinese Teochew populations, southeast of China.21,22 In addition, our results illustrated that Cd burden was positively associated with clinical stage and node grade,22 suggesting Cd burden may contribute to NPC progression. Nonetheless, a cause-and-effect association between chronic Cd exposure and the malignant progression of NPC has not been established.

Mechanistically, oxidative stress, one of the primary mechanisms involved in heavy-metal-mediated carcinogenesis, has been implicated in Cd carcinogenesis and causes most of the genotoxic events such as DNA strand breaks, chromosomal aberration and gene mutations.23 However, direct interaction of Cd with DNA is minimal. Epigenetic alterations, including hypermethylation, have been suggested to the predominant molecular processes involved in Cd-induced carcinogenesis,24–26 and also contribute to NPC carcinogenesis.27,28 A few signaling pathways have been identified deregulated by DNA methylation in NPC, including the MAPK, Hedgehog, TGF-β and Wnt signaling.29 Promoter methylation-induced silence of some Wnt inhibitors has been linked with the aberrant activation of Wnt signaling and transcription of its downstream targets.30

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has emerged as a key signaling pathway promoting malignancy in mouse kidney and triple-negative breast cancer cells with chronic Cd exposure.31,32 However, the precise mechanism by which Cd mediates Wnt signaling has not been elucidated, especially epigenetic regulation of some core components of this pathway. CK1α, consisting of the “destruction complex” with Axin, APC, Ser/Thr kinases glycogen synthase kinase 3β for phosphorylating and proteolytically degrading cytoplasmic β-catenin, is known to be a key factor determining β-catenin stability and transcriptional activity in tumor cells.19 Since downregulation of CK1α in melanoma cells correlated with promoter methylation and induction of β-catenin signaling to promote metastasis,33 we hypothesized that chronic Cd exposure promoted NPC cell growth and metastatic potential through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by epigenetic modulation of CK1α.

This is the first study to reveal the stimulative effect of chronic Cd exposure on malignant progression of NPC. In particular, we suggest an epigenetic mechanism involved in Cd carcinogenesis by upregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

CNE-1 and CNE-2 cell lines were a gift from Dr. Ya Cao (Xiangya Hospital, Hunan, People’s Republic of China) and maintained in our laboratory.34,35 Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (HIMEDIA, Mumbai, India) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cd chloride (purity 99%; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in double-distilled water to make a 1M stock solution. For cytotoxicity assessment, cells were placed in 96-well plates for 24 hours and then incubated with various concentrations of Cd (1 nM, 1 μM and 1 mM) for 72 hours. For the chronic exposure experiment, cell lines were continuously exposed to a non-toxic level (1 μM) of Cd for up to 10 weeks (23 passages). To distinguish Cd-exposed cells from their parental cells, the cells exposed to Cd for 10 weeks were designated as CCT-NPC cells including CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells. We used Cd-free cultured CNE-1 and CNE-2 cells as controls. This study was performed with the approval of the Human Ethical Committee of the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College.

Cell treatment

To investigate the mechanism responsible for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation and CK1α downregulation, CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells (1×106) were treated with 0, 5, 10, or 50 μM 5-aza-CdR (Santa Cruz, Dallas, Texas, USA) for 48 hours, after which cells were harvested and genomic DNA, total RNA and total protein were extracted, and then subjected to methylation specific-PCR (MS-PCR), RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. Simultaneously, the cell characteristics were evaluated by MTT assays and transwell assay. Control cultures were treated under similar experimental conditions in the absence of 5-aza-CdR. To further identify the modulating role of CK1α in Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation induced by Cd, CK1α was silenced by small interfering RNA (siRNA) in CCT-CNE1 cells. The sequences of the siRNAs used to suppress CK1α were as follows: forward: 5-CUCAGGAUUAAACCAGUUATT-3 and reverse: 5-UAACUGGUUUAAUCCUGAGTT-3. Both the siRNA and control sequences were ordered from GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, People’s Republic of China). Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 3,000 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After that, the β-catenin protein level and mRNA levels of its downstream genes were determined by Western blot and RT-PCR, respectively. The analysis was repeated three times.

MTT assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)–2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was conducted to quantify cell viability by the protocol described previously.36 Briefly, exponentially growing cells (1×104 cells/well) in 100 μL medium were seeded in 96-well plates. The dye crystals were dissolved in 100 μL DMSO and the absorbance was measured with a Multiskan MK3 reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 492 nm. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate wells.

Colony formation assay

Exponentially growing cells were suspended in RPMI-1640 medium and seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 200 cells per well. The plates were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for two weeks. After fixation in paraformaldehyde, the colonies were stained with Giema for 10 minutes and then counted using a light microscope. The cloning efficiency (%)=(number of colonies formed)/(number of cells added)×100. All groups were assessed in triplicate.

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell migration and invasion were measured using transwell chambers (8 μm pore size; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) according to methods described previously.37 600 μL 10% FBS-supplemented RPMI-1640 medium was added to the lower chamber. The invasion chambers were pre-coated with 50 μL Matrigel solution. 1×105 cells were layered in the upper chambers and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours (migration assay) and 48 hours (invasion assay). Cells adhering to the lower surface of the membrane were fixed by methanol, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (migration) or Giemza (invasion) and counted under a light microscope. Experiments were independently performed in triplicate.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as previously described37 using monoclonal antibodies against β-actin, β-catenin, (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), CK1α (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology) as well as E-cadherin, N-cadherin and Vimentin (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), at 4°C overnight followed by rinsing and addition of an anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody (Gene Tech, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) at 1:1,000 dilution for 1 hour. Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China).

Immunofluorescence analysis

Each group of cells was washed and treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 minutes. After blocking with goat serum for 30 minutes, the fixed and blocked cells were incubated with primary anti-β-catenin (rabbit antihuman, 1:100; Cell Signaling Technology), CK1α (rabbit anti human, 1:100; (Cell Signaling Technology) and actin filament antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:2,000; ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) conjugated with rhodamine (Santa Cruz, Dallas, Texas, USA) for 1 hour at 37°C. Actin filament was stained with rhodamine phalloidin (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO, USA) for 30 minutes. Finally, nuclei were stained with DAPI (Beyotime). Fluorescence images were then taken with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from untreated and Cd-treated CNE-1 and CNE-2 cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) and cDNA was prepared using reverse transcriptase PCR kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). RT-PCR was conducted as previously described37 using primers designed with Primer Express Software version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, Canada): cyclin D1 forward 5-TGTCCTACTACCGCCT CACA-3 and reverse 5-CAGGGCTTCGATCTGCTC-3; cyclin E forward 5-AAAAGGTTTCAGGGTATCAG-3 and reverse 5-TGTGGGTCTGTATGTTGTG-3; c-myc forward 5-GCCCCTCAACGTTAGCTTCA-3 and reverse 5-TTCCAGATATCCTCGCTGGG-3; c-jun forward 5-AAGAACTCGGACCTCCTCAC-3 and reverse 5-CTCCTGCTCATCTGTCACG-3; β-actin forward 5-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT-3 and reverse 5-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT-3. Gene expression relative to β-actin was determined by the comparative CT method (2−ΔΔCT). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Dual luciferase assay

CNE-1 and CCT-CNE1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates overnight and then transiently transfected with TOPflash reporter plasmid (400 ng/well; Millipore, MA, USA) and Renilla luciferase plasmid (100 ng/well; Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) by Lipofectamine 3,000 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA). Luciferase activity was measured at 48 hours after transfection by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Pro-mega), and normalized to Renilla luciferase relative light unit values. Three independent experiments were performed.

MS-PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from cell lines with different treatments to detect the methylation status of the CK1α in a promoter CpG island. MS-PCR was conducted as described previously.36 The primer sets were as follows: unmethylated forward (5′-TGTGTAGTTAGTAGGAGTTGTAGTGT-3), unmethylated reverse (5′-AAAAAT-CAACAACAAAAAAACAAA-3′), and methylated forward (5′-TTGCGTAGTTAGTAG-3′), methylated reverse (5′-AAATCGACAACGAAAAAACGA-3′), which amplified 116- and 115 bp products respectively.

Tumor xenografts

All animal studies were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shantou University Medical College and followed the guidelines of the Animal Laboratory Center. Four-week-old BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Vital River (Beijing, People’s Republic of China) and maintained under pathogen-free conditions according to standard institutional guidelines. CNE-1 and CCT-CNE1 cells were harvested at a concentration of 3×106 cells/mL. For tumor xenograft experiments, mice were injected subcutaneously in the right axilla with 100 μL of cell suspension (n=5 per group). Tumor volumes (width2×length×0.5) were obtained by serial caliper measurement every 3 days. At 28 days after injection, the mice were euthanized and tumors were removed and weighed.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical procedures were performed with SPSS software. Measurement data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

NPC cells exhibit increased cell growth in vitro and in vivo after chronic Cd exposure

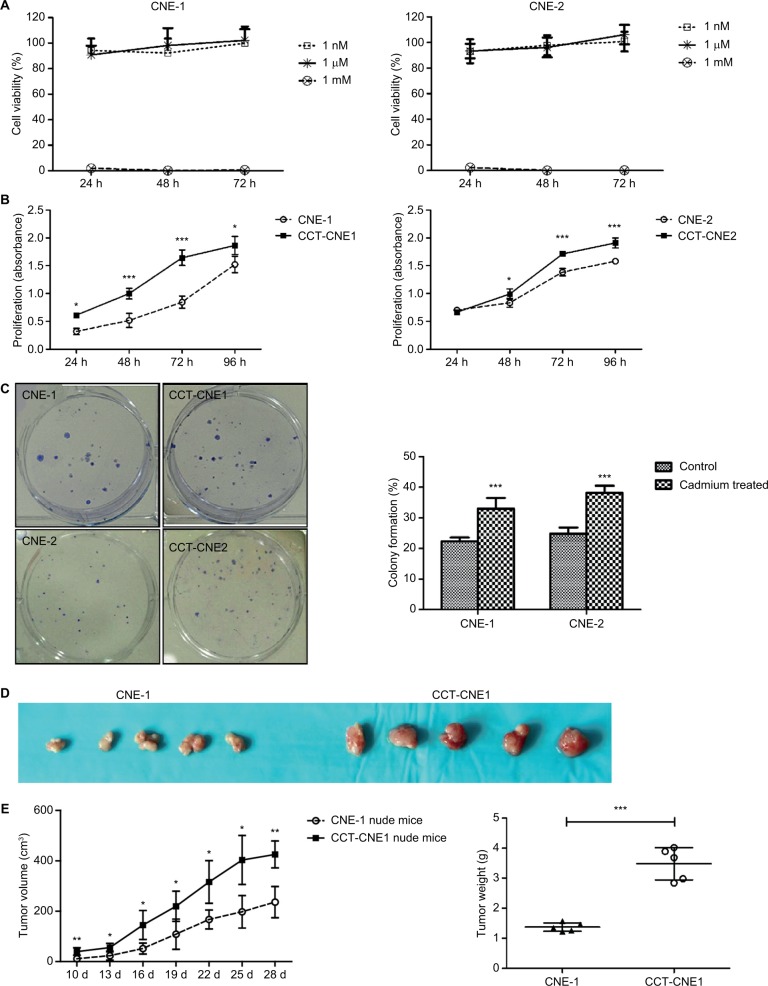

Before chronic exposure, a non-cytotoxic concentration for treatment of NPC cells was first identified. In 72 hours of exposure, neither 1 nM nor 1 μM Cd reduced cell survival in either CNE-1 or CNE-2 cell lines, whereas 1 mM Cd exerts a cytotoxic effect such that viable cells are rarely found at 24 hours (Figure 1A). This indicates that micromolar exposure is not acutely toxic, and even improves cell viability slightly compared to nanomolar exposure. Based on continuous Cd exposure previously shown in other research,32,38 1 μM was selected for our chronic exposure concentration in NPC. After 10 weeks of exposure to low level of Cd (1 μM), MTT assay showed that cell viability was significantly increased in CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells compared to the parental cells (Figure 1B, P<0.05). Also, the colony formation capacity of CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells was markedly increased, 1.48 and 1.54-fold, respectively (Figure 1C, P<0.01). We further explored tumorigenesis of CCT-CNE1 cells in vivo. At 10 days after injection, CCT-CNE1 xenograft tumors exhibited increased growth compared to CNE-1 transplanted controls (Figure 1D and E). These results collectively illustrate that CCT-NPC cell lines acquire a more proliferative phenotype, both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation, colony formation and xenograft tumor growth in CCT-NPC or parental cells.

Notes: (A) MTT assays for acute exposure to Cd (1 nM, 1 µM and 1 mM). (B) MTT assays following 1 µM Cd treatment for 10 weeks. (C) Effects of chronic Cd exposure on the colonogenic ability in CNE-1/CNE-2 and CCT-CNE1/CCT-CNE2 cells (N=3). (D) Gross appearance of xenograft tumors at 28 days after CNE-1 or CCT-CNE1 cells injection. (E). Tumor growth curves and weight data in transplanted nude mice with CNE-1 and CCT-CNE1 through four weeks; data are mean (± SD) tumor volume (N=5). Each assay was performed in triplicate. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, compared with the parental cells.

Abbreviation: CCT-NPC, chronic cadmium-treated nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Chronic Cd exposure promotes NPC cell invasion and migration

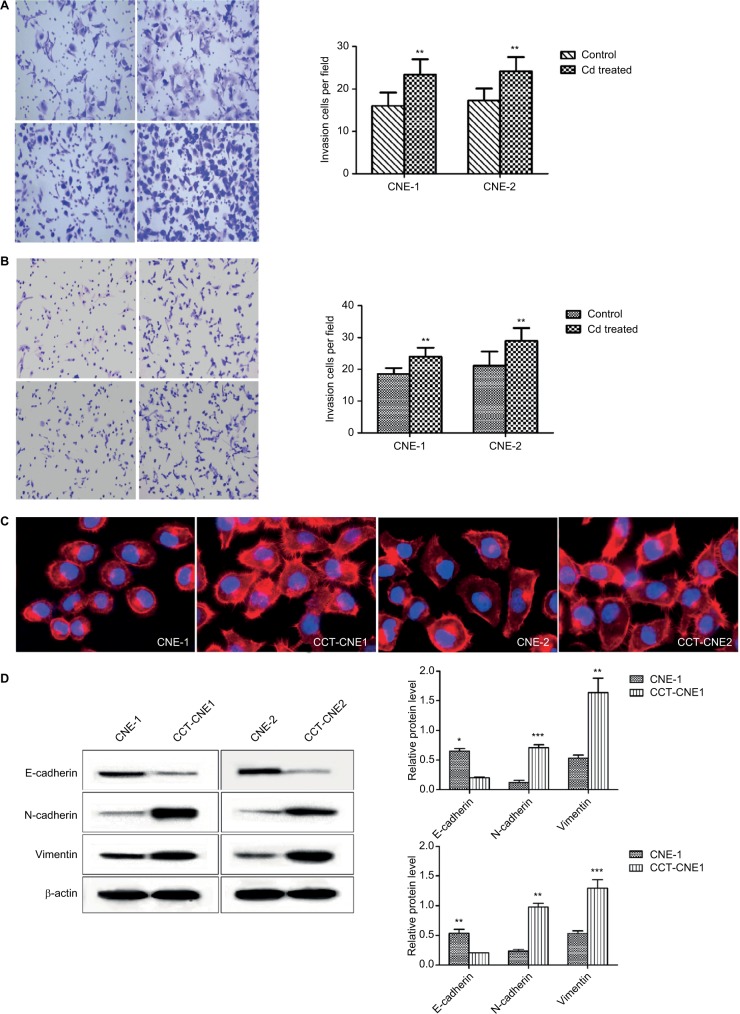

Transwell assays were performed to determine the effect of Cd on cell aggressiveness. The results showed that the invasive capacity of CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells was markedly increased 1.46 (P<0.01) and 1.40-(P<0.01) fold of the parental controls, respectively (Figure 2A). Analogously, CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 displayed robust migration compared to their parental cell lines, as the number of transmigrated cells was 1.30 and 1.37 times greater than that of CNE-1 (P<0.001) and CNE-2 (P<0.01) cells, respectively (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

CCT-NPC cells acquired metastasis-associated phenotype.

Notes: (A) The gross view of cell invasion assay stained with Giemza and corresponding quantitative analyses of the results for CCT-NPC cells and the control cells. Magnification 200×. (B) The gross view of cell migration assay stained with hematoxylin-eosin and corresponding quantitative analyses of the results for CCT-NPC cells and the control cells. Magnification 200×. (C) Immuno-fluorescence staining for actin filament in CCT-NPC cells and the parental cells. Actin filament cytoskeleton was stained with rhodamine conjugated phalloidin (red) and nuclei with DAPI (blue). Magnification 400×. (D) Expression of the EMT markers E-cadherin, vimentin and N-cadherin in CCT-NPC and NPC cell lines. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, compared with the parental cells. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, compared with the parental cells.

Abbreviations: CCT-NPC, chronic cadmium-treated nasopharyngeal carcinoma; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition.

Chronic Cd exposure induces cytoskeleton reorganization and promotes EMT

It is commonly accepted that the dynamic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton as well as EMT are prerequisites for cancer cells to gain invasive and metastatic properties.39,40 Actin filament is one of the most important components of the cytoskeleton and changes in intracellular actin structures are a key step in cellular migration and invasion and closely related to EMT.39,41–43 Therefore, immunofluorescence analysis was used to study the influence of Cd on the actin filament distribution. Both CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells exhibited more dense, highly labeled microtubule network compared to the parental cell lines, displaying actin filament assembly and formation of migratory membrane protrusions (Figure 2C), which provides evidence of cytoskeleton reorganization. It is widely accepted that tumor invasiveness and metastasis are also caused by motility and EMT. Hence, the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin was determined by Western blot. As expected, both CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 had increased vimentin and N-cadherin and decreased E-cadherin expression compared to controls, suggesting that chronic Cd treatment promotes NPC EMT (Figure 2D).

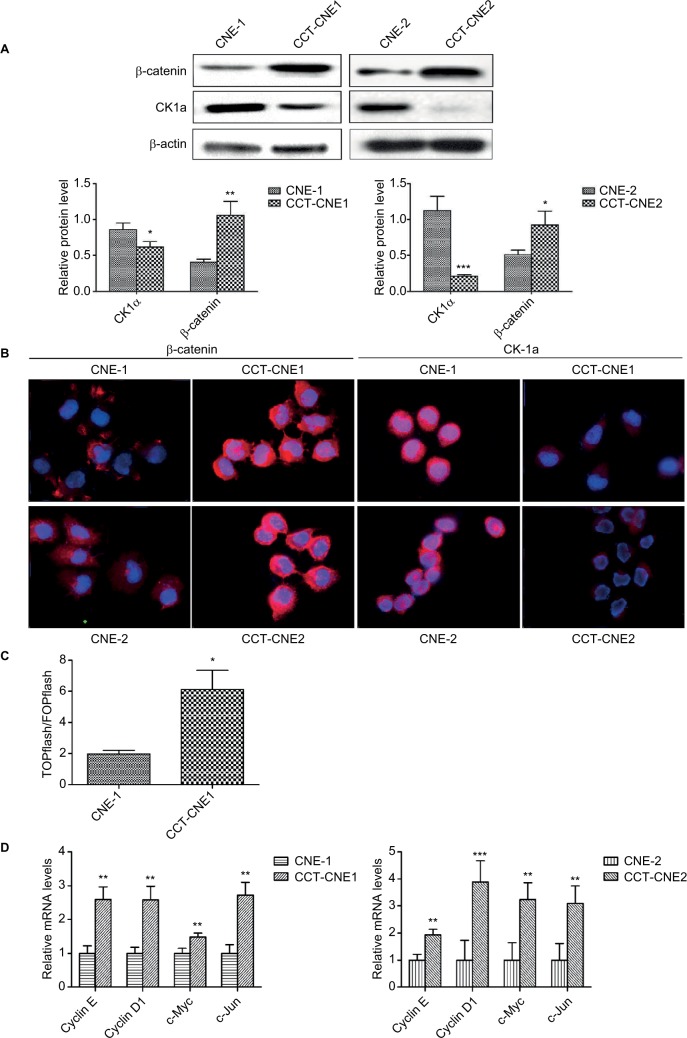

Chronic Cd treatment induces activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

Before exploring whether the Wnt signaling pathway was activated in CCT-NPC cell lines, we detected the protein expression of β-catenin and CK1α by Western blot. Compared to primary NPC cells, a remarkable upregulation of β-catenin was found in both CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cell lines, whereas the protein level of CK1α was reduced in CCT-NPC cells (Figure 3A). These were corroborated by immunofluorescence microscopy that exhibited a more diffused intense signal of β-catenin, preferentially localized in the nucleus in CCT-NPC cells, compared to the controls with a weak plaque-like signal, predominately in the cytoplasm. Conversely, CK1α was strongly expressed in the cytoplasm and nucleus of parental cells, whereas a weak signal was observed in CCT-NPC cells (Figure 3B). TOP/FOPflash luciferase reporter gene assay was further performed to assess the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. There was a 3.11 fold increase of luciferase activity in CCT-CNE1 cells compared to CNE-1 cells, suggesting increased TCF/LEF-mediated transcription following Cd exposure (Figure 3C). This was further confirmed by the observation of elevated transcription of well-known Wnt target genes including cyclin D1, cyclinE, c-Myc and C-jun (Figure 3D).These results indicate that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling was activated in response to continuous low-level Cd exposure in NPC cells.

Figure 3.

Cd treatment activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling and aberrant methylation of the CK1α promoter in NPC cell lines.

Notes: (A) Western blot analysis of total β-catenin and CK1α in cCd-treated NPC cells and controls; β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Immunofluorescence staining patterns of β-catenin and CK1α in NPC and CCT-NPC cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (magnification 400×). (C) Luciferase reporter assays using TOPflash/FOPflash reporter plasmids to assess the activity of Wnt/β-catenin. (D) RT-PCR analysis of relative transcript levels of the β-catenin target genes cyclin E, cyclin D1, c-Myc and c-Jun. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Abbreviations: CCT-NPC, chronic cadmium-treated nasopharyngeal carcinoma; CK1α, casein kinase 1α; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR.

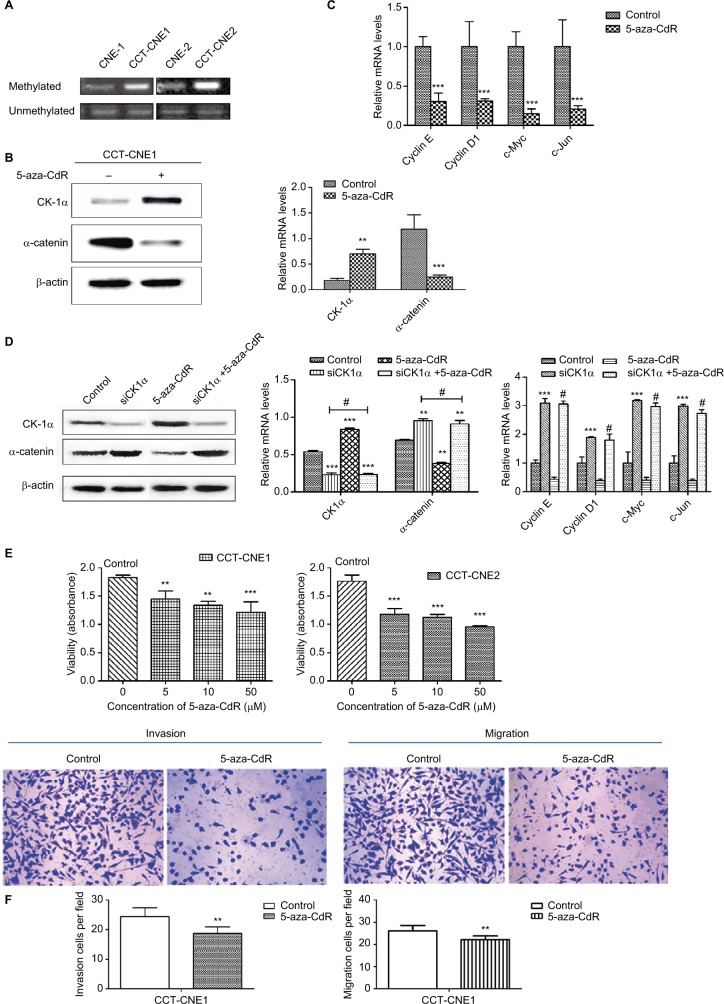

Hypermethylation of CK1α plays a mediating point for Wnt pathway activation and malignant progression in CCT-NPC cells

It has been suggested that epigenetic inactivation of negative Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulators contributes to aberrant activation of this signaling pathway in NPC tumorigenesis.44 Besides, aberrant DNA methylation plays an important role in Cd-induced carcinogenesis.24 Given that the DNA hyper-methylation induced by Cd is responsible for the reduction of CK1α, thereby activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, we next analyzed the methylation status of CK1α. The results of MSP assays revealed that the CK1α promoter region is highly methylated in both CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells, whereas only slight methylation was detected in their parental cells (Figure 4A), suggesting that the decreased expression of CK1α is attributed to hypermethylation of the promoter CpG island induced by Cd in CCT-NPC cells.

Figure 4.

Hypermethylation of CK1α induces a switch in Wnt/β-catenin signaling and malignant progression in CCT-NPC cells.

Notes: (A) Methylation status of the CK1α promoter analyzed by MS-PCR. (B) Western blot analyses of CK1α and β-catenin in CCT-CNE1 cells following treatment with 50 µM 5-aza-CdR for 48 hours. (C) RT-PCR analysis of relative transcript levels of β-catenin target genes following treatment of cells with 5-aza-CdR (50 µM). (D) Western blot and RT-PCR analyses of the effect of CK1α depletion and (or) 5-aza-CdR treatment on β-catenin expression and downstream gene transcription in CCT-CNE1 cells. (E) MTT assays for cell viability of CCT-CNE1 and CCT-CNE2 cells with increasing concentrations of 5-aza-CdR treatment. (F) Invasion and migration ability of 5-aza-CdR-treated CCT-CNE1 cells. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, compared with parental cells. #P>0.05, compared with CK1α treated cells.

Abbreviations: CCT-NPC, chronic cadmium-treated nasopharyngeal carcinoma; CK1α, casein kinase 1α; MS-PCR, methylation specific-PCR; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Then we treated CCT-CNE1 cells with 5-aza-CdR to address the hypothesis that hypermethylated CK1α induced by Cd is involved in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation and malignant progression of CCT-NPC cells. As expected, the expression of CK1α was found to be restored by 5-aza-CdR, while the β-catenin protein level (Figure 4B) as well as the transcription of target genes including cyclin D1, cyclinE, c-Myc and C-jun was downregulated following 5-aza-CdR treatment (Figure 4C). Additionally, in order to exclude the nonspecific effects of 5-aza-CdR, we knocked down the CK1α with RNA interference assay. The data show that the knockdown of CK1α blocked the downregulation effect of 5-aza-CdR on β-catenin protein level and its downstream target genes’ mRNA level (Figure 4D). We think these data strongly support that hypermethylation of CK1α induces a switch in Wnt/β-catenin signaling in CCT-CNE1 cells. Finally, we found that treatment of CCT-NPC cells with 5-aza-CdR suppressed cell proliferation (Figure 4E), invasion and migration (Figure 4F). In summary, these results highlight that the hypermethylation of the promoter of CK1α induced by Cd may serve as a master governor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation to promote malignant phenotypes.

Discussion

In the present study, CNE-1 and CNE-2 cells were continuously exposed to 1 μM Cd, a non-toxic level, for up to 10 weeks to mimic chronic low-level Cd exposure. It has been revealed that Cd can trigger a hormesis-like response characterized by a low-dose stimulation and a high-dose inhibition in human cells of mammary, prostate, embryo lung fibroblast and embryonic kidney.45–48 In the present study, exposure of CNE-1 and CNE-2 cells to Cd at concentration of 1 μM for 10 weeks also exerts a stimulatory role in cell proliferation in vitro. Furthermore, injection of nude mice with CCT-CNE1 cells induced marked increase in xenograft tumor volume compared to the parental cells. These findings are consistent with previous reports that long-term exposure to low concentrations of Cd induces cell proliferation and tumor growth and thus promotes malignant transformation in human lung cells, bronchial epithelial cells and prostate epithelial cells.38,49,50

NPC is a malignant tumor with high rates of local invasion and distant metastasis. With considerable improvement in radiotherapy technology and advances in multimodal treatment over the past three decades, excellent local control for NPC can generally be achieved, but distant metastasis becomes the major pattern of treatment failure for NPC.51 Metastasis, a major feature of malignant tumors, is a multi-step process including dissemination, migration, intravasation, extravasation, and colonization to form secondary tumors.52 Previous studies have suggested that chronic exposure of human bronchial, lung, prostate or breast epithelial cells to Cd induces malignant transformation with hyperproliferation and increased potential to invade and migrate.49,53,54 Recently, Wei And Shaikh reported that prolonged Cd treatment in triple-negative breast cancer cells stimulates cell proliferation, adhesion, cytoskeleton reorganization as well as migration and invasion.32 In this study, we describe for the first time that chronic low-dose Cd exposure not only confers NPC cells a growth advantage in vitro and in vivo, but also stimulates metastasis-associated phenotype, as evidenced by enhanced invasion and migration, cytoskeleton reorganization, upregulation of mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin as well as repression of epithelial marker E-cadherin. The present study provides experimental evidence for the findings of our preliminary human study that Cd seems to be a risk factor for NPC and may promote the occurrence and development of this disease.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been implicated in a number of cancers including NPC, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma, and leukemia. Abnormalities of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway also have been indicated to be involved in Cd nephro-carcinogenesis,31,55–57 in which Cd enhances nuclear translocation of β-catenin in human renal epithelial cells followed by binding to TCF/LEF and inducing target genes transcription to upregulate cell proliferation and survival.56 Similarly, our study shows that chronic Cd treatment induces the protein expression and nuclear translocation of β-catenin and upregulates luciferase activity as well as the transcription of the downstream genes including cyclin D1, cyclin E, c-myc and c-jun, suggesting chronic Cd exposure elicits the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Since Wnt/β-catenin pathway is believed to play a pivotal role in multiple malignancies including cell proliferation, EMT and migratory process,58–63 our results strongly suggest that chronic Cd exposure induces activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling to accelerate cell proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT in NPC cells.

Although Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been documented to participate in Cd carcinogenicity, little is known regarding the precise mechanism of how Cd mediates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mutations in some components of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, such as mutation of β-catenin at position Ser45 or mutations in APC or Axin, have been described in cancers and considered as inappropriate activation of the Wnt pathway.64 However, present consensus is that the direct muta-genic effect of Cd is weak or just restricted to comparatively high-concentration exposure.5 Chronic Cd exposure has been linked with increases in DNA methyltransferase activity and global 5mC and aberrant DNA methylation of some DNA repair genes or tumor suppressor genes, such as RASSF1A and p16 in Cd-induced malignant transformation.50,65 Aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling is also a critical component of NPC and most NPC tumors exhibit Wnt/β-catenin pathway protein dysregulation. It has been shown that decreased expression of the Wnt inhibitory factor, an endogenous Wnt antagonist, is silenced via promoter hypermethylation in NPC cell lines.66

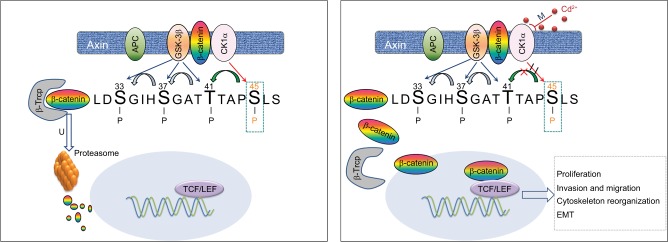

CK1α, a component of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, has been proposed as a negative regulator of this pathway by phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser45. Inhibition or down-regulation of CK1α leads to an accumulation of cytoplasmic β-catenin.67 A recent study identified CK1α was a novel tumor suppressor in melanoma cells as evidence that knockdown of CK1α enhanced the invasive capacity of melanoma cells and this effect was overexpression of CK1α in metastatic melanoma cells resulted in suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and reduction of cell growth and metastasis.33 Surprisingly, very little is known about whether Cd activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by targeting CK1α. Results from this study demonstrate that chronic Cd exposure induces decreased expression of CK1α due to the hypermethylated promoter region in NPC. And we also found that 5-aza-CdR treatment restores the expression of CK1α and induces β-catenin degradation and thus blocks the transcription of downstream genes (cyclin D1, cyclinE, c-Myc and C-jun). Furthermore, knockdown of CK1α by siRNA before 5-aza-CdR treatment suppressed 5-aza-CdR-induced alterations of β-catenin level and downstream genes transcription in CCT-CNE1 cells. It appears that CK1α acts as a target for Cd-induced hyper-methylation and induces a switch in Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Moreover, further functional analyses indicate that treatment with demethylation agent in CCT-NPC cells causes impaired cell proliferation, invasion and migration. These findings are supportive of our hypothesis that methylation of CK1α induced by Cd might be responsible for the induction of malignant phenotype in NPC cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hypothesized model for the induction of Cd on Wnt/β-catenin signaling and malignant progression in NPC cells.

Notes: Chronic low-dose Cd treatment of NPC cells induces CK1α promoter hypermethylation that downregulates CK1α expression, leading to accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin thereby activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling to promote malignancy.

Abbreviations: APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; CK1α, casein kinase α; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; TCF/LEF, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor; β-Trcp, β-transducin repeats-containing proteins.

Conclusion

Taken together, this study highlights for the first time, to our knowledge, that NPC cells exposed to chronic low-dose Cd acquired enhanced malignant progression, including more proliferative and aggressive characteristics, at least in part, by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway via DNA methylation of CK1α in promoter CpG islands.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81602886), The Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong province (No. 2016A030313062), and Science and Technology Planning Project of Shantou City, People’s Republic of China (No. 2015-113). We thank Dr. Stanley Lin for his constructive comments and Prof. Yukun Cui for his kindly gift of luciferase plasmid.

Abbreviations

- Cd

Cadmium

- NPC

nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- CCT-NPC

chronic cadmium-treated nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- CK1α

casein kinase 1α

- 5-aza-CdR

5-aza-2-deoxy-cytidine

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-PCR, MS- PCR, methylation-specific PCR

- CpG

methylated cytosine-guanine. TCF/LEF, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor

Footnotes

Author contributions

Lin Peng, Fan Zhang and Jiong-Yu Chen carried out the experiments. Lin Peng and Fan Zhang wrote the original draft. Yi-Teng Huang reviewed and revised the manuscript. Fan Zhang contributed to the statistical analysis. Yi-Teng Huang conceived and designed the work. Jiong-Yu Chen and Xia Huo supervised the overall project. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Faroon O, Ashizawa A, Wright S, et al. Toxicological Profile for Cadmium. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC Beyllium, cadmium, Hg, and exposure in the glass manufacturing industry. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1993;58:19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stayner L, Smith R, Thun M, Schnorr T, Lemen R. A quantitative assessment of lung cancer risk and occupational cadmium exposure. IARC Sci Publ. 1992(118):447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolonel L, Winkelstein W. Cadmium and prostatic carcinoma. Lancet. 1977;2(8037):1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartwig A. Cadmium and cancer. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013;11:491–507. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5179-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satarug S. Long-term exposure to cadmium in food and cigarette smoke, liver effects and hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13(3):257–271. doi: 10.2174/138920012799320446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julin B, Wolk A, Bergkvist L, Bottai M, Akesson A. Dietary cadmium exposure and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based prospective cohort study. Cancer Res. 2012;72(6):1459–1466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Julin B, Wolk A, Johansson JE, Andersson SO, Andrén O, Akesson A. Dietary cadmium exposure and prostate cancer incidence: a population-based prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(5):895–900. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mezynska M, Brzóska MM. Environmental exposure to cadmium-a risk for health of the general population in industrialized countries and preventive strategies. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25(4):3211–3232. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0827-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akesson A, Julin B, Wolk A. Long-term dietary cadmium intake and postmenopausal endometrial cancer incidence: a population-based prospective cohort study. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6435–6441. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksen KT, Halkjær J, Sørensen M, et al. Dietary cadmium intake and risk of breast, endometrial and ovarian cancer in Danish postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cartularo L, Laulicht F, Sun H, Kluz T, Freedman JH, Costa M. Gene expression and pathway analysis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells treated with cadmium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;288(3):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strumylaite L, Kregzdyte R, Bogusevicius A, Poskiene L, Baranauskiene D, Pranys D. Association between cadmium and breast cancer risk according to estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2: epidemiological evidence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145(1):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Il’yasova D, Schwartz GG. Cadmium and renal cancer. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kido T, Honda R, Tsuritani I, Ishizaki M, Yamada Y, Nogawa K. High urinary cadmium concentration in a case of gastric cancer. Br J Ind Med. 1989;46(4):288. doi: 10.1136/oem.46.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feki-Tounsi M, Hamza-Chaffai A. Cadmium as a possible cause of bladder cancer: a review of accumulated evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014;21(18):10561–10573. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Esquinas E, Pollan M, Tellez-Plaza M, et al. Cadmium exposure and cancer mortality in a prospective cohort: the strong heart study. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(4):363–370. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chua MLK, Wee JTS, Hui EP, Chan ATC. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Li Y, Semenov M, et al. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell. 2002;108(6):837–847. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsa N. Environmental factors inducing human cancers. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(11):1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khlifi R, Olmedo P, Gil F, et al. Risk of laryngeal and nasopharyngeal cancer associated with arsenic and cadmium in the Tunisian population. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014;21(3):2032–2042. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-2105-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng L, Wang X, Huo X, et al. Blood cadmium burden and the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-control study in Chinese Chaoshan population. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015;22(16):12323–12331. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engström KS, Vahter M, Johansson G, et al. Chronic exposure to cadmium and arsenic strongly influences concentrations of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine in urine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(9):1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang B, Li Y, Shao C, Tan Y, Cai L. Cadmium and its epigenetic effects. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(16):2611–2620. doi: 10.2174/092986712800492913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takiguchi M, Achanzar WE, Qu W, Li G, Waalkes MP. Effects of cadmium on DNA-(Cytosine-5) methyltransferase activity and DNA methylation status during cadmium-induced cellular transformation. Exp Cell Res. 2003;286(2):355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang B, Li Y, Tan Y, et al. Low-dose Cd induces hepatic gene hypermethylation, along with the persistent reduction of cell death and increase of cell proliferation in rats and mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai W, Cheung AK, Ko JM, et al. Comparative methylome analysis in solid tumors reveals aberrant methylation at chromosome 6p in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4(7):1079–1090. doi: 10.1002/cam4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JS, Kim SY, Lee M, Kim SH, Kim SM, Kim EJ. Radioresistance in a human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma cell line is associated with DNA methylation changes and topoisomerase II α. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(4):558–566. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1017154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai W, Zheng H, Cheung AK, Lung ML. Genetic and epigenetic landscape of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2016;5(2):16. doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.03.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Zhang Y, Fan Y, et al. Characterization of the nasopharyngeal carcinoma methylome identifies aberrant disruption of key signaling pathways and methylated tumor suppressor genes. Epigenomics. 2015;7(2):155–173. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakraborty PK, Scharner B, Jurasovic J, Messner B, Bernhard D, Thévenod F. Chronic cadmium exposure induces transcriptional activation of the Wnt pathway and upregulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers in mouse kidney. Toxicol Lett. 2010;198(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei Z, Shaikh ZA. Cadmium stimulates metastasis-associated phenotype in triple-negative breast cancer cells through integrin and β-catenin signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;328:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinnberg T, Menzel M, Kaesler S, et al. Suppression of casein kinase 1alpha in melanoma cells induces a switch in beta-catenin signaling to promote metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(17):6999–7009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye XX, Liu CB, Chen JY, Tao BH, Zhi-Yi C. The expression of cyclin G in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its significance. Clin Exp Med. 2012;12(1):21–24. doi: 10.1007/s10238-011-0142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong CQ, Ran YG, Chen JY, Wu X, You YJ. Study on promoter methylation status of E-cadherin gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2010;39(8):532–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X, Zhuang YX, Hong CQ, et al. Clinical importance and therapeutic implication of E-cadherin gene methylation in human ovarian cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(8):100. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li XY, Lin YC, Huang WL, et al. Zoledronic acid inhibits proliferation and impairs migration and invasion through downregulating VEGF and MMPs expression in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):714–720. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Son YO, Wang L, Poyil P, et al. Cadmium induces carcinogenesis in BEAS-2B cells through ROS-dependent activation of PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;264(2):153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun BO, Fang Y, Li Z, Chen Z, Xiang J. Role of cellular cytoskeleton in epithelial-mesenchymal transition process during cancer progression. Biomed Rep. 2015;3(5):603–610. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasquier J, Abu-Kaoud N, Al Thani H, Rafii A. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in a Clinical Perspective. J Oncol. 2015;2015:792182. doi: 10.1155/2015/792182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nürnberg A, Kitzing T, Grosse R. Nucleating actin for invasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(3):177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrc3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacquemet G, Hamidi H, Ivaska J. Filopodia in cell adhesion, 3D migration and cancer cell invasion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;36:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shankar J, Messenberg A, Chan J, Underhill TM, Foster LJ, Nabi IR. Pseudopodial actin dynamics control epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(9):3780–3790. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ying Y, Tao Q. Epigenetic disruption of the WNT/beta-catenin signaling pathway in human cancers. Epigenetics. 2009;4(5):307–312. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.5.9371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hao C, Hao W. Role of ERK in the hormesis induced by cadmium chloride in HEK293 cells. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2011;40(4):517–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt CM, Cheng CN, Marino A, Konsoula R, Barile FA. Hormesis effect of trace metals on cultured normal and immortal human mammary cells. Toxicol Ind Health. 2004;20(1–5):57–68. doi: 10.1191/0748233704th192oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang G, Duan W, Xu L, Song S, Zhu C, Wu L. Biphasic effect of cadmium on cell proliferation in human embryo lung fibroblast cells and its molecular mechanism. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23(6):973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaddipati JP, Rajeshkumar NV, Grove JC, et al. Low-Dose Cadmium Exposure Reduces Human Prostate Cell Transformation in Culture and Up-Regulates Metallothionein and MT-1G mRNA. Nonlinearity Biol Toxicol Med. 2003;1(2):199–212. doi: 10.1080/15401420391434333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Person RJ, Tokar EJ, Xu Y, Orihuela R, Ngalame NN, Waalkes MP. Chronic cadmium exposure in vitro induces cancer cell characteristics in human lung cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;273(2):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Waterland RA, Dill AL, Webber MM, Waalkes MP. Tumor suppressor gene inactivation during cadmium-induced malignant transformation of human prostate cells correlates with overexpression of de novo DNA methyltransferase. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(10):1454–1459. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee AW, Ma BB, Ng WT, Chan AT, Bb M, Wt N. Management of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Current Practice and Future Perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3356–3364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coghlin C, Murray GI. Current and emerging concepts in tumour metastasis. J Pathol. 2010;222(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/path.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Tokar EJ, Diwan BA, Dill AL, Coppin JF, Waalkes MP. Cadmium malignantly transforms normal human breast epithelial cells into a basal-like phenotype. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(12):1847–1852. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Achanzar WE, Diwan BA, Liu J, Quader ST, Webber MM, Waalkes MP. Cadmium-induced malignant transformation of human prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(2):455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thévenod F, Chakraborty PK. The role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in renal carcinogenesis: lessons from cadmium toxicity studies. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10(4):387–404. doi: 10.2174/156652410791316986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chakraborty PK, Lee WK, Molitor M, Wolff NA, Thévenod F. Cadmium induces Wnt signaling to upregulate proliferation and survival genes in sub-confluent kidney proximal tubule cells. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:102. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thévenod F, Wolff NA, Bork U, Lee WK, Abouhamed M. Cadmium induces nuclear translocation of beta-catenin and increases expression of c-myc and Abcb1a in kidney proximal tubule cells. Biometals. 2007;20(5):807–820. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anastas JN, Moon RT. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(1):11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Li L, Huang Q, et al. Wnt signaling through Snail1 and Zeb1 regulates bone metastasis in lung cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(2):748–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novellasdemunt L, Antas P, Li VS. Targeting Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer. A Review in the Theme: Cell Signaling: Proteins, Pathways and Mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;309(8):C511–C521. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00117.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dimeo TA, Anderson K, Phadke P, et al. A novel lung metastasis signature links Wnt signaling with cancer cell self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5364–5373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398(6726):422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeong WJ, Yoon J, Park JC, et al. Ras stabilization through aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes intestinal tumorigenesis. Sci Signal. 2012;5(219):ra30. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polakis P. Wnt signaling in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(5):a008052. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luevano J, Damodaran C. A review of molecular events of cadmium-induced carcinogenesis. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2014;33(3):183–194. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.2014011075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin YC, You L, Xu Z, et al. Wnt signaling activation and WIF-1 silencing in nasopharyngeal cancer cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341(2):635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amit S, Hatzubai A, Birman Y, et al. Axin-mediated CKI phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser 45: a molecular switch for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 2002;16(9):1066–1076. doi: 10.1101/gad.230302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]