Summary box.

Nigeria has a high magnitude of blindness and visual impairment and in addition, there is inequity in accessing eye care.

Primary eye care (PEC) activities in Nigeria have largely been donor driven and unsustainable partly due to primary healthcare (PHC) system challenges.

Nigeria’s current administration is implementing Universal Health Coverage through a revitalised PHC system.

The WHO has recently piloted a PEC package for sub-Saharan Africa (WHO AFRO PEC package).

Nigeria has the opportunity to leverage on the revitalised PHC and the recently developed WHO AFRO PEC package to implement equitable and accessible PEC and achieve universal eye health.

Introduction

An estimated 253 million people are blind or visually impaired worldwide, 90% of whom live in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 In Nigeria, a LMIC, approximately 4.25 million adults are blind or visually impaired with over 80% of the blindness from avoidable causes.2 Cataract is the most common cause of blindness in Nigeria and is readily treatable by surgery. Refractive errors, which can readily be treated by spectacles, are the most common cause of visual impairment. However, the Nigerian national blindness survey showed that almost half of all eyes that had a procedure for cataract had been couched (a traditional procedure for clearing the visual axis as a treatment for cataract3), with poor visual outcomes and <5% of those with refractive errors had spectacles.4 5 Lack of accessible eye care services and lack of awareness of where to seek services are some of the reasons why patients remain visually impaired or seek unorthodox treatment, even though outcomes are poor.6

Other eye conditions which cause ocular morbidity for which access to eye care is needed include presbyopia (age-related decline in near vision), allergic/infective conjunctivitis and other conditions which may cause distress and warrant treatment at the primary level. A recent survey showed that one in four Nigerians (ie, approximately 43 million) have at least one ocular morbidity.7 Nigeria has 3.3 ophthalmologists/million population, which while higher than the sub-Saharan regional average of 2.2, is less than the four recommended.8 The majority of ophthalmologists are concentrated in urban areas,8 therefore, the greater number of Nigerians, who live in rural areas, may have to travel long distances to access care. In the absence of accessible orthodox eye care, patients access other sources, for example, patent medicine vendors, traditional healers and couchers, which may exacerbate the visual loss through harmful practices or delay appropriate treatment. A study in Nigeria reported that over a third of people with eye problems who sought care had consulted these alternative sources.7 Eye conditions like presbyopia and conjunctivitis which can be treated at the primary level are principally delivered at secondary and tertiary level in Nigeria,9 10 resulting in inequity in access and higher costs for patients and providers.

There is an epidemic of diabetes globally, including in African countries, and diabetic retinopathy (DR) is increasing as a cause of visual impairment. In Nigeria, the prevalence of diabetes has been reported to be 3.3%, 20.5% of whom had DR.11 While there are major screening challenges for DR at the primary healthcare (PHC) level, facilities can offer blood sugar testing, health education and referral to services for the detection and management of DR.

There is a need for LMICs to provide universal access to eye care for blinding conditions and for conditions that cause ocular morbidity. As early as 1984, the World Health Organisation (WHO) advocated a PHC approach to increase access to eye care.12 Primary eye care (PEC) is an integrated, participatory and inclusive approach to the eye health component of PHC consisting of promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative services.13 To realistically implement PEC, health workers should receive adequate training to be knowledgeable and skilled in the management (identification, treatment or referral) of eye diseases, be properly equipped, have access to consumables, be adequately supervised and have access to referral centres.

There is a dearth of rigorous research into the effectiveness of PEC in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and reports from a few SSA countries have not been encouraging, highlighting challenges such asa lack of skills to manage eye conditions resulting in inappropriate treatment, delayed referrals and failure to refer serious conditions.14 Other challenges include inadequate supervision, a dearth of equipment and supplies, absenteeism and high staff turnover.15

A national survey to assess the population need for PEC in Rwanda showed that nearly a third of the population had the potential to benefit from PEC, particularly older persons and women.16 To actualise the benefits of PEC, PEC should be part of a continuum of care from community to tertiary level, with each level functioning well and supported by good referral systems between them. This can be actualised in a comprehensive eye care programme. For example, the Rwandan government has streamlined the activities of eye-care collaborators to optimise resources, launching a comprehensive PEC programme in collaboration with Vision for a Nation to develop and implement PEC. Secondary level services have been strengthened with support from the Fred Hollows Foundation and Christoffel-Blinden Mission. Equity in the geographical distribution of PEC services and provision of health insurance have improved access to eye care and demand for services at secondary and tertiary levels has increased to the extent that eye conditions are now the second most common reason for seeking healthcare in Rwanda.17 In the Gambia, in 1986, PEC was included as part of a National Comprehensive Eyecare strategy. This strategy led to a reduction in blindness from 0.7% to 0.42% over 10 years after adjusting for population growth.18 In both countries, PEC was included as part of a National Comprehensive Eyecare strategy, so the contribution of PEC is difficult to quantify.

Strengths and challenges of integrating PEC into PHC in Nigeria

To effectively integrate PEC into PHC, a functional PHC system is crucial, as PEC can only be as strong as the primary-health structure into which it is integrated.14 However, the PHC system in Nigeria is beset with challenges which include, but are not limited to, inadequate infrastructure, shortage of health workers, absenteeism19 and a dearth of basic equipment.20 Furthermore, poor governance, conflict and inadequate prioritisation of health systems have added to the deterioration of frontline health facilities.21 Hence, despite the availability of PHC services, rural communities in Nigeria tend to underuse them due to perceptions of poor quality and inadequacy of services.22

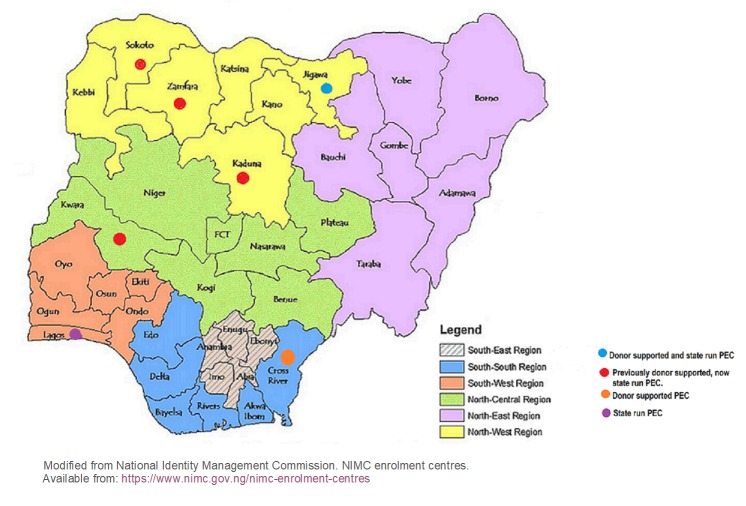

Despite these PHC challenges, some states in Nigeria have integrated eye-care into PHC, but these have been largely donor driven. In Nigeria as in many LMICs, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) provide a significant proportion of eye-care services.23 It is thought that NGOs fill the gap because of the ‘relative invisibility’ of eye-care by governments.24 The NGOs involved in PEC in Nigeria include Sightsavers, Christoffen-Blindenmission (CBM), the Evangelical Church of West Africa and the Tulsi Chanrai Foundation (TCF). This does not include the private sector or organisations that run eye-care programmes (including PEC) outside the government health system. Figure 1 shows the location of integrated PEC activities in Nigeria.

Figure 1.

Location of integrated PEC activities in Nigeria. PEC, primary eye care.

The NGO-led PEC programmes are not without challenges and have produced mixed results. The broad aim of the Sightsavers-supported programme was to reduce preventable blindness through the provision of sustainable outreach, primary and secondary referral services using a health systems’ strengthening approach. The programme covered all the districts in Sokoto, Kwara, Kaduna and Zamfara states, with one eye clinic providing services for a cluster of districts. These were integrated into PHC activities in the states. An evaluation of the Sokoto eye-care programme shows that although the prevalence of unoperated cataract remains high, there has been a sevenfold increase in cataract surgical coverage (the proportion of people who have received cataract surgery as a percentage of all those who could have benefited from cataract surgery) and a doubling of the cataract surgical rate (he number of cataract operations performed per million population/year) since the inception of the programme.25 Again, this was part of a comprehensive blindness reduction strategy and the contribution of PEC could not be ascertained. A report from a recent audit of the Kwara Eye Health Programme (KEHP) showed that 40% of facilities were unable to sustain services due to insufficient government support (personal communication, Sightsavers KEHP, 2016). In Kaduna state, Sightsavers achieved its target of providing services in at least 70% of districts. However, the failure of the programme to maintain a skilled workforce at the primary level has affected sustainability.26

In Jigawa state, PEC activities are supported principally by CBM in conjunction with the Evangelical Church of West Africa (ECWA) eye hospital. There is also a tangible commitment to eye-care by the state government with a budget line of 1.1% of the state health budget pledged for eye-care including PEC. Despite this, Jigawa state experiences challenges from an inadequately skilled PEC workforce.27 In Cross Rivers State, the TCF trained 176 PHC workers in PEC, but full implementation of services was stalled by lack of counterpart government funding (personal communication, TCF 2016).

A major limitation of the NGO-led initiatives in Nigeria is that activities largely ceased when funding for in-service training ended. Increasing access to eye-care is not a challenge that can be overcome by the NGO sector alone and a paradigm shift is needed in how eye health services are planned, coordinated and resourced at all levels.28 Governmental support reinforced by implementable policies is key for eye-care programme implementation. The Lagos state government has trained 167 health workers in 141 primary health centres in eye-care who refer cases to eight general hospitals with eye departments. Although 4902 patients with eye conditions attended the PHCs between January and April 2011, there are limited data on the quality of the service or the number of patients referred.29

A major challenge of PEC in SSA is that there has been no consensus on the scope of practice in the PHC system, competencies required or a defined curriculum, which has resulted in deficient training and supportive supervision.14 As a consequence, in Nigeria, each implementing body has developed their own set of competencies, curricula and have trained different cadres in PEC. The National Primary Health Care Development Agency in Nigeria (NPHCDA) has recently rolled out a revised preservice curriculum for PHC workers, which includes a more comprehensive curriculum on eyecare. There is also a revised Standard Operating Procedure booklet (called National Standing Orders) for PHC workers with guidelines on how to manage a few eye conditions. However, PEC focused on the clinical component alone15 30 cannot lead to successful PEC outcomes. PEC requires a package of interventions, that is, eye health promotion, basic equipment for eye examination, a supply of medication and consumables, referral mechanisms, supervision, health information and referral/feedback systems, financing mechanisms and strong government commitment. PEC implementation will remain high on rhetoric and low on delivery if the entire package is not addressed.

Opportunities afforded by new initiatives

In December 2014, the National Health Bill was signed into law in Nigeria and became the National Health Act. The Act empowers communities to be responsible for their own health and, if properly implemented, should strengthen the PHC system.31 It includes funding for health insurance at front-line facilities and eligible secondary centres, provision of essential drugs, vaccines and consumables, provision and maintenance of facilities, equipment and transport, human resources for health and counterpart funding for health projects in the district. The equivalent of $150 million has been included in the 2018 budget to implement the Act.32 This is the first time budgetary provision has been made to implement the National Health Act and is indicative of government commitment to PHC reforms. In addition, Nigeria’s current administration has launched a bold initiative: ‘ Accelerating progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) through PHC’ to provide equitable access for all Nigerians to quality healthcare using PHC as a vehicle to achieve this. The Federal Ministry of Health through the NPHCDA and the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) are implementing this initiative as part of its mandate to work with states to revitalise PHC service delivery.

Currently, there is increased global and regional support for PEC. The World Health Assembly through the Global Action Plan 2014–2019 stresses the importance of PEC in attaining Universal Eye Health, calling on member states to include PEC in PHC.33 In addition, WHO AFRO has developed competencies for all eye health personnel, including those providing PEC, for the region which will be launched on World Sight Day, on 11 October 2018.34 Furthermore, to encourage uniformity and address all components of PEC in SSA, WHO recently developed a package of interventions (WHO AFRO PEC) which was informed by workshops, expert meetings and has been pilot tested in Rwanda and Kenya.

It has been suggested that this package has the potential to strengthen eye health systems and improve coverage.34 The key components are health promotion and facility-based interventions, with algorithms to guide clinical management of eye conditions and a set of standards and indicators for monitoring and evaluation.35

In Nigeria, in order to be scalable, the WHO AFRO PEC package needs to be integrated into the initiatives to revitalise PHC and included in preservice training. To ensure financial sustainability and financial risk protection, the WHO AFRO PEC Package should be included in the essential package for eye-care in UHC plans and the NHIS. Despite the magnitude of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria, eye-care ranks low in priority for healthcare.36 The WHO AFRO PEC package, if well implemented, has the capacity to empower communities to take charge of their eye health and benefit from the national momentum towards achieving UHC. This aspiration is based on the premise that the revitalised PHC will overcome the inefficiencies and mistakes of the past and evolve into a more functional and efficient service.

Almost all the ingredients are now in place for the successful integration of eye-care into PHC: a renewed global focus on PHC; national PHC reforms and pro-poor health financing mechanisms; an enabling global policy environment for PEC and a tailor-made PEC package for SSA. However, sustained government support is crucial. In addition, continuous economic evaluation of PEC should inform how scarce resources should be deployed. Furthermore, any strategy to successfully implement PEC in Nigeria needs to be pragmatic, building on the evidence of what works in different settings but adapted to the local context.

Conclusion

PEC may not be the silver bullet to solve the eye-care needs of a population. Although there is limited high quality evidence of the effectiveness of PEC, the literature suggests that implementation of PEC as part of a comprehensive eye-care strategy could increase access to eye-care.

With global and regional support for PEC and strong government commitment to PHC reform, Nigeria has the opportunity to implement PEC, potentially making eye-care accessible and equitable for all her citizens.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: AEA, NI and CG drafted the initial manuscript. HF helped with subsequent revisions. AEA, CG and HF read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was made possible by a scholarship from the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust’s Commonwealth Eye Health Consortium. The opinions and conclusions arrived at are solely those of the authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, et al. . Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e888–97. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kyari F, Gudlavalleti MV, Sivsubramaniam S, et al. . Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: the National Blindness and Visual Impairment Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:2033–9. 10.1167/iovs.08-3133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilbert CE, Murthy GV, Sivasubramaniam S, et al. . Couching in Nigeria: prevalence, risk factors and visual acuity outcomes. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2010;17:269–75. 10.3109/09286586.2010.508349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rabiu MM, Kyari F, Ezelum C, et al. . Review of the publications of the Nigeria national blindness survey: methodology, prevalence, causes of blindness and visual impairment and outcome of cataract surgery. Ann Afr Med 2012;11:125–30. 10.4103/1596-3519.96859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ezelum C, Razavi H, Sivasubramaniam S, et al. . Refractive error in Nigerian adults: prevalence, type, and spectacle coverage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:5449–56. 10.1167/iovs.10-6770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tafida A, Gilbert C. Exploration of indigenous knowledge systems in relation to couching in Nigeria. African Vision and Eye Health 2016;75 10.4102/aveh.v75i1.332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Senyonjo L, Lindfield R, Mahmoud A, et al. . Ocular morbidity and health seeking behaviour in Kwara state, Nigeria: implications for delivery of eye care services. PLoS One 2014;9:e104128 10.1371/journal.pone.0104128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palmer JJ, Chinanayi F, Gilbert A, et al. . Mapping human resources for eye health in 21 countries of sub-Saharan Africa: current progress towards VISION 2020. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:44 10.1186/1478-4491-12-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adepoju F, Abdulraheem I. Clinico-epidemiological pattern of eye diseases at University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital: a one year review. Tropical Journal of Health Sciences 2005;12:40–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott S, Ajaiyeoba A. Eye diseases in general out-patient clinic in Ibadan. Nigerian journal of medicine: journal of the National Association of Resident Doctors of Nigeria 2002;12:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kyari F, Tafida A, Sivasubramaniam S, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors for diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: results from the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1299 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization Strategies for the prevention of blindness in national programmes: a primary health care approach. World Health Organization, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Du Toit R. An overview of primary eye care in Sub-Saharan Africa 2006-2012. Compiled for International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, 2014. Available from: https://iapblive.blob.core.windows.net/resources/3_An-Overview-of-PEC-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa_2006-2012.pdf [Accessed 25 Sep 2018].

- 14. Courtright P, Seneadza A, Mathenge W, et al. . Primary eye care in sub-Saharan African: do we have the evidence needed to scale up training and service delivery? Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2010;104:361–7. 10.1179/136485910X12743554760225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalua K, Gichangi M, Barassa E, et al. . A randomised controlled trial to investigate effects of enhanced supervision on primary eye care services at health centres in Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14(Suppl 1):S6 10.1186/1472-6963-14-S1-S6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bright T, Kuper H, Macleod D, et al. . Population need for primary eye care in Rwanda: a national survey. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193817 10.1371/journal.pone.0193817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Binagwaho A, Scott K, Rosewall T, et al. . Improving eye care in Rwanda. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:429–34. 10.2471/BLT.14.143149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faal H, Minassian DC, Dolin PJ, et al. . Evaluation of a national eye care programme: re-survey after 10 years. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:948–51. 10.1136/bjo.84.9.948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abimbola S, Olanipekun T, Igbokwe U, et al. . How decentralisation influences the retention of primary health care workers in rural Nigeria. Glob Health Action 2015;8:26616 10.3402/gha.v8.26616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kress DH, Su Y, Wang H. Assessment of primary health care system performance in nigeria: using the primary health care performance indicator conceptual framework. Health Systems & Reform 2016;2:302–18. 10.1080/23288604.2016.1234861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walley J, Lawn JE, Tinker A, et al. . Primary health care: making Alma-Ata a reality. Lancet 2008;372:1001–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61409-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sule SS, Ijadunola KT, Onayade AA, et al. . Utilization of primary health care facilities: lessons from a rural community in southwest Nigeria. Niger J Med 2008;17:98–106. 10.4314/njm.v17i1.37366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morone P, Camacho Cuena E, Kocur I, et al. . Securing support for eye health policy in low- and middle-income countries: identifying stakeholders through a multi-level analysis. J Public Health Policy 2014;35:185–203. 10.1057/jphp.2013.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmer JJ, Gilbert A, Choy M, et al. . Circumventing 'free care' and 'shouting louder': using a health systems approach to study eye health system sustainability in government and mission facilities of north-west Tanzania. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:68 10.1186/s12961-016-0137-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Muhammad N, Adamu MD, Caleb M, et al. . Changing patterns of cataract services in North-West Nigeria: 2005-2016. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183421 10.1371/journal.pone.0183421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matafeni T, Isiyaku S. Strengthening health systems in Kaduna State: investing in the health workforce and partnership for eye health. Insight 2009;1. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ibrahim J. Evaluation of primary eye care services in Jigawa state North-western Nigeria. a dissertation submitted to the london school of hygiene & tropical medicine in conformity with the requirements for the degree of MSc, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness , IAPB Africa human resources for eye health strategic plan. 2014. Available from: http://www.iapbafrica.co.za/resource/resourceitem/493/1 [Accessed 20 Oct 2014].

- 29. Lagos State ministry of Health , Blindness prevention programmes. 2014. Available from: https://health.lagosstate.gov.ng/blindness-prevention-programme-bpp/

- 30. Byamukama E, Courtright P. Knowledge, skills, and productivity in primary eye care among health workers in Tanzania: need for reassessment of expectations? Int Health 2010;2:247–52. 10.1016/j.inhe.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Federal Republic of Nigeria The National Health Act. Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, 2014: A139–72. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Federal Republic of Nigeria National Assemmbly Appropriations bill 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization , Universal eye health: a global action plan 2014–2019. 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/blindness

- 34. Graham R. Facing the crisis in human resources for eye health in sub-Saharan Africa. Community Eye Health 2017;30:85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organisation Report of the expert group meeting to assess and validate a package for eye health interventions at the primary level for the African Region, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ogundimu KO. Case study: improving the management of eye care programmes. Community Eye Health 2008;21:60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]