Abstract

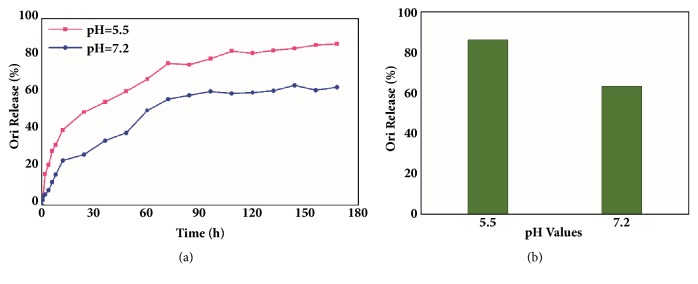

Drug delivery carriers with a high drug loading capacity and biocompatibility, especially for controlled drug release, are urgently needed due to the side effects and frequent dose in the traditional therapeutic method. Guided by nanomaterials, we have successfully synthesized zirconium-based metal−organic frameworks, Zr-TCPP (TCPP: tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin), namely, PCN-222, which is synthesized by solvothermal method. And it has been designed as a drug delivery system (DDS) with a high drug loading of 38.77 wt%. In our work, PCN-222 has achieved pH-sensitive drug release and showed comprehensive SEM, TEM, PXRD, DSC, FTIR, and N2 adsorption-desorption. The low cytotoxicity and good biocompatibility of PCN-222 were certificated by the in vitro results from an MTT assay, DAPI staining, and Annexin V/PI double-staining even cultivated L02 cells and HepG2 cells for 48h. Furthermore, Oridonin, a commonly used cancer chemotherapy drug, is adsorbed into PCN-222 via the solvent diffusion technique. Based on an analysis of the Oridonin release profile, results suggest that it can last for more than 7 days in vitro. And cumulative release rate of Ori at the 7 d was about 86.29% and 63.23% in PBS (pH 5.5 and pH 7.2, respectively) at 37°C. HepG2 cells were chosen to research the cytotoxicity of PCN-222@Ori and free Oridonin. The results demonstrated that the PCN-222@Ori nanocarrier shows higher cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells compared to Oridonin.

1. Introduction

In the past two decades, microporous metal−organic frameworks (MOFs), combined by different metal ions or clusters and organic ligands [1] giving rise to a crystalline structure, were widely used in gas adsorption and separation [2], supercapacitor electrode [3, 4], catalysis [5], waste-water purification [6], fluorescence detection [7], magnetism [8], etc. Recently, MOFs have an exhibited great potential in the biomedical domain especially as drug delivery carriers to control delivery of target drugs due to its several promising capabilities [9]. MOFs have an irresistible advantage as favorite drug carrier, such as extra-high porosity and surface areas [10], tunable and tailorable particle size [11], designable host-guest interaction [12], multiple topologies [13], modifiable chemical surface [14], and being stable enough under biological conditions [15, 16]. Based on the above research, a variety of novel drug delivery systems (DDS) can be designed, such as high loading capacity of different guest molecules [17], tumor targeted treatment [18], drugs release in response to external stimuli such as pH, temperature, light irradiation, and redox reagents [19–22]. Therefore, MOFs can improve drugs solubility [23], change the pharmacokinetics of drugs [24, 25], prolong circulation time [26], significantly enhance the antitumor effect [27], minimize the dosage, and reduce toxic side effects [28].

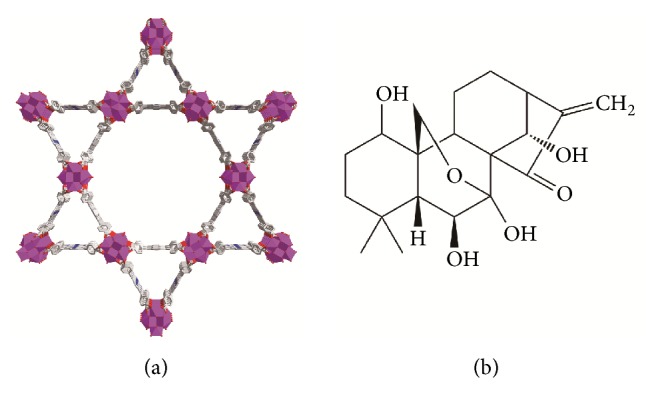

The Zr6 cluster is thought to be a perfect building block to synthesize the mixed-linker MOFs, because of their intrinsic open frameworks, superior stability, and adjustable connectivity [29]. Therefore, Zr-MOFs, as a class of new porous skeleton material, have gained wide applications due to their ultrahigh surface areas and being more stable in the aqueous phase than general Fe/Zn/Cu/Cd-based MOFs [30]. Porous coordination network (PCN-222) is a kind of MOF formed by zirconium chloride octahydrate and meso-tetra (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin; nanoporous structure is shown in Figure 1(a). The original design target of preparing PCN-222 (Zr6(μ-OH)8(OH)8(CO2)8) is to be as biomimetic catalysts [31], and then it is applied to the label-free detection of a phosphoprotein (α-casein) [32]. In biomedical applications, Zr-MOFs can form Zr−O−P bonding while maintaining its integrity frameworks; therefor, Zr-MOFs have high affinity with organophosphorus species [33]. Although several biocompatible porous MOFs were explored as drug delivery, Zr6 and porphyrin-based MOFs remain to be reported.

Figure 1.

Structural diagram. (a) schematic illustration for the construction of PCN-222 and (b) the chemical structure of Oridonin.

Oridonin (Ori) is a well-known ent-kaurene tetracyclic diterpenoid compound (Figure 1(b)) isolated from the Chinese medicinal herb Rabdosia rubescens [34] with various pharmacological actions. Ori has raised wide attention, in recent years, because of its conspicuous antitumor activity, such as gastric cancer [35], multiple myeloma [36], triple negative breast cancer [37, 38], hepatocellular carcinoma [39], breast cancer [38], prostate cancer [40], oral cancer [41], and osteosarcoma [42]. Pharmacological study shows that the chief anticarcinomatous mechanism of Ori lies in the following: (1) significant antimutagenic effect, (2) inhibiting sodium pump activity, (3) antiangiogenic activity, (4) inducing cell apoptosis [34, 43, 44], etc. However, the Ori with poor solubility, instability in chemical property, short biological half-life, and active group (α-methylene-cyclopentanone) was easily deactivated, which severely prevents its clinical applications [45]. Therefore, it was necessary to prepare a kind of sustained-release preparations to prolong the half-lifetime, increase the bioavailability, and reduce the side effect of Ori. But so far, research on Ori delivery material is rare. Studies on sustained-release or controlled-release preparations of Ori were restricted to the most familiar carriers, such as galactosemia chitosan [46], HP-β-cyclodextrin [47], poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid [48], and graphene oxide [49]. Although drug stability and efficacy improved by the above pharmaceutical methods, as we know, drug loading capability of organic carrier is disappointed and inorganic carrier is difficult to be degraded and removed from body [50]. One of the important research directions is to develop or synthesize a suitable drug carrier of Ori.

Based on the above thought, we have successfully synthesized a biocompatible Zr-based nanoscale MOFs (PCN-222) with unique advantage, high load dose, nontoxicity, biocompatibility, pH-sensitive release, etc. We aim to prepare a PCN-222@Ori sustained-release and controlled-release drug delivery system by using PCN-222 load Ori. To the best of our knowledge, PCN-222 is the first MOF that carries Oridonin.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

The synthesis of PCN-222 was realized by dissolving meso-tetra (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP, 0.4g) and zirconium chloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2·8H2O, 2.0g) in 500 mL of dry N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and 300 mL of formic acid. The mixture was placed in a round bottom flask equipped with a condenser and was kept stirring and heated for three days at 408 K under air. The mixture was returned to room temperature. Dark red solid was recovered by filtration. In order to remove unreacted starting ligands, inorganic species, as-synthesized PCN-222 (~100mg) samples were immersed into 100mL DMF with 3mL of 4M HCl at 120°C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the supernatant was carefully decanted and washed with DMF and acetone for three times. Fresh acetone was subsequently added, and the sample had a right to stay for 8h to exchange and remove the nonvolatile solvates (DMF) and this process was repeated six times. After removal of acetone by decanting, the sample was activated by drying under vacuum for 6h.

The synthesized PCN-222 was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (the samples that need checking were fixed on the aluminum sample column with carbon conductive tape and observed after the gold sputtering treatment 2.5min, SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan), transmission electron microscopy (the samples were mixed by anhydrous alcohol, a drop of the prepared solution was transferred to the carbon film coated grids for overnight drying, TEM, JEM-1230, Japan), N2 adsorption-desorption at 77K (Micromeritics ASAP 2020, USA), powder X-ray diffraction (Cu-Kα, λ =1.541nm, 40Kv/40mA, XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV, Japan), and enzyme-sign instrument of multiple function (the PCN-222 was mixed by high purity water, transferred into 96-well plate (plate, clear bottom black with lid), and its fluorescence property was determined, Molecular Devices SpectraMax i3X, USA).

2.2. Cell Culture, Cytotoxicity Assay, Imaging, and Annexin V/PI Double-Staining Assay

Human hepatoma cells (HepG2, Jenniobio Biotechnology, China) and human normal hepatocyte cells (L02, Jenniobio Biotechnology, China) were incubated in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5 % CO2) for two or three days employing DMEM (Coning, USA) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, China) and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin solution (USA). The cytotoxicity of PCN-222 at various concentrations (0, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μg/mL) was evaluated through standard MTT assays used L02 cells. And the anticancer activity of free Ori and PCN-222@Ori was assessed by HepG2 cells. After that, the MTT solution with a concentration of 5 mg/mL was added to each well and incubated for another 4 h. Culture supernatant was removed and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 150 mL) was added to each well, and then the plate was shaken for 10 min. The absorbance of each well was read at λ= 570nm in a microplate reader (Thermo, Multiskan GO, USA). All tests were repeated for three times and the data were averaged, having the exact same protocol to evaluate the antitumor activity of the Ori (0, 10, 15, 20 μg/mL) and PCN-222@Ori. In order to further evaluate the biocompatibility of PCN-222, the leakage rate of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was assayed for the evaluation of the cell membrane intact. After the L02 cells were treated with PCN-222 (0, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μg/mL) for 48, the supernatant was collected, and LDH activity was determined with a commercial kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Besides, L02 cells were seeded with PCN-222 in a 6-well plate and incubated for 48 h. For each well, culture supernatant was removed and fixed by using 4% paraformaldehyde (500 mL) for 10 min at room temperature. Apart from that, the fixed cells were washed two times by using 0.5 mL PBS and stained with a DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) solution for 5 min to visualize nuclear DNA. Thereafter, the cells were washed three times with PBS (1.0 mL) and nuclear changes were analyzed using confocal laser scanning microscopes (Olympus, IX73, Japan). What is more, an Annexin V-FITC detection kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) was used to exam the cell apoptosis [51, 52] by flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II, USA).

2.3. Preparation and Characterization of PCN-222@Ori

The PCN-222@Ori pH-sensitive nanoparticles were prepared by the solvent diffusion technique (QESD). Ori (400.48 mg, Nantong Feiyu Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China) was dissolved in methanol and made into 8.0 mg/mL standard solutions. The dried PCN-222 (3 mg) with a different amount of the standard solution in Xilin bottles was subject to magnetic stirring at room temperature. The orthogonal design L9 (33) was implemented to ensure the optimum process. And we studied how the ratio of drug to PCN-222 (A), mixing time (B), and the amount of solvent (C) influenced the process of loading. SEM, TEM, XRD, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (studied by the KBr method, FTIR, Thermo Fisher Nicolet6700, USA), and differential scanning calorimetry (the samples were placed on a flat-bottomed aluminum plate and tested at 40-300°C, heating rate of 10°C/min, and nitrogen flow rate of 50 mL/min, DSC, Mettler-Toledo Stare, Switzerland) were used to describe its characteristics.

2.4. Measurement of the Drug Loading Capacity

PCN-222@Ori was precipitated through methanol cleaning twice and centrifuging (9500 rpm, 15 min) after 2d, 3d, or 4d. The supernatant of methanol was collected and its concentration of Ori was determined by HPLC (Methanol: Water = 55: 45, λ = 295 nm) via an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 system. And the formulae of PCN-222 loading capacity (LC) is as follows: LC%=(M0-M1)/M×100% (M0 and M1 are the initial amount and the final amount of Ori (mg) in the system, respectively. M denotes the amount of PCN-222@Ori (mg)).What is more, to get the exact amount of Ori in PCN-222@Ori, the 1H-NMR spectra (Bruker 800MHz AVANCE III HD with a cryoprobe) of alkaline-digested PCN-222@Ori are analyzed. The relevant signals of TPCC ligands are then integrated against those of Ori, resulting in peak radios of about 1:0.075, implying the mole ratios of TCPP/Ori is about 1:0.6.

2.5. In Vitro Ori Release Profile

For the determination of the impregnated drug molecule release from the PCN-222@Ori, an in vitro cumulative Ori release study was performed in various pH environments. A semipermeable dialysis bag diffusion technique (dialysis bag, MW3400, MD34 mm, USA) was implemented to evaluate the cumulative drug release. Firstly, approximately 10mg of PCN-222@Ori was dispersed at pH7.2 (100mL) followed by incubation at 37°C, and then exactly the same experimental procedure was executed at pH5.5 (100mL). At the given time, 3 mL of the digestion liquor was collected, and the equivalent volume of fresh PBS was added. And the digestion liquor was filtered through a 0.45μm polytetrafluoroethylene membrane filters for Ori analysis. The cumulative percentage of Ori release was determined by using HPLC via an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 system in comparison with a standard curve of free Ori (Y=26292X– 8127, r2 = 0.999, from 0.06μg/mL to 84.0 μg/mL) at regular predetermined time intervals. The release mechanism was analyzed by zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Weibull, and Ritger-Peppas equations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. PCN-222 Nanocomposites Preparation and Characterization

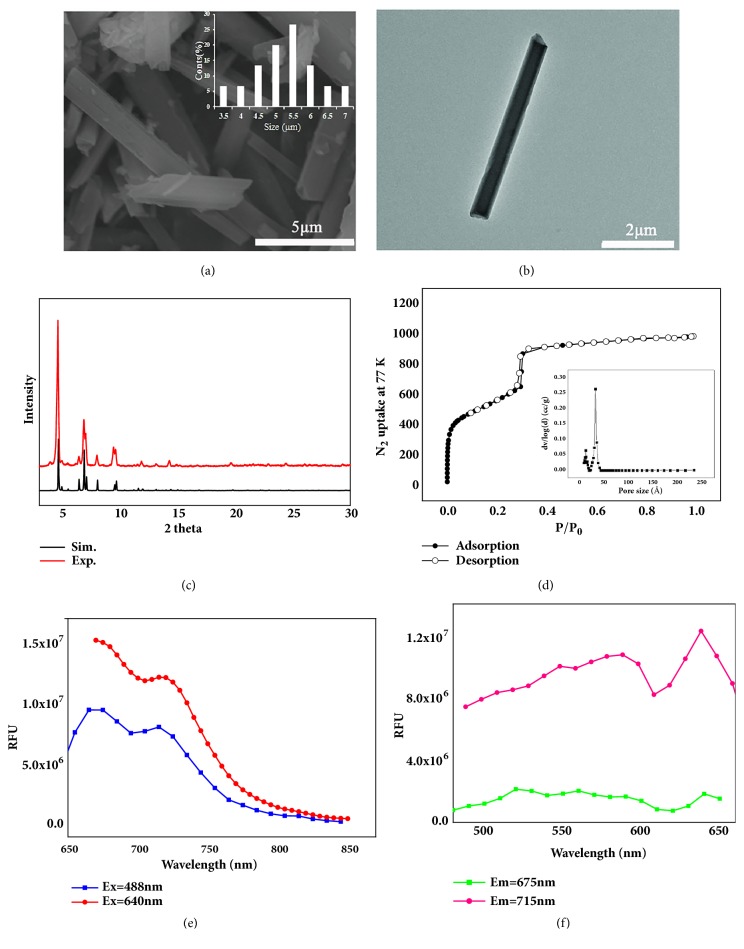

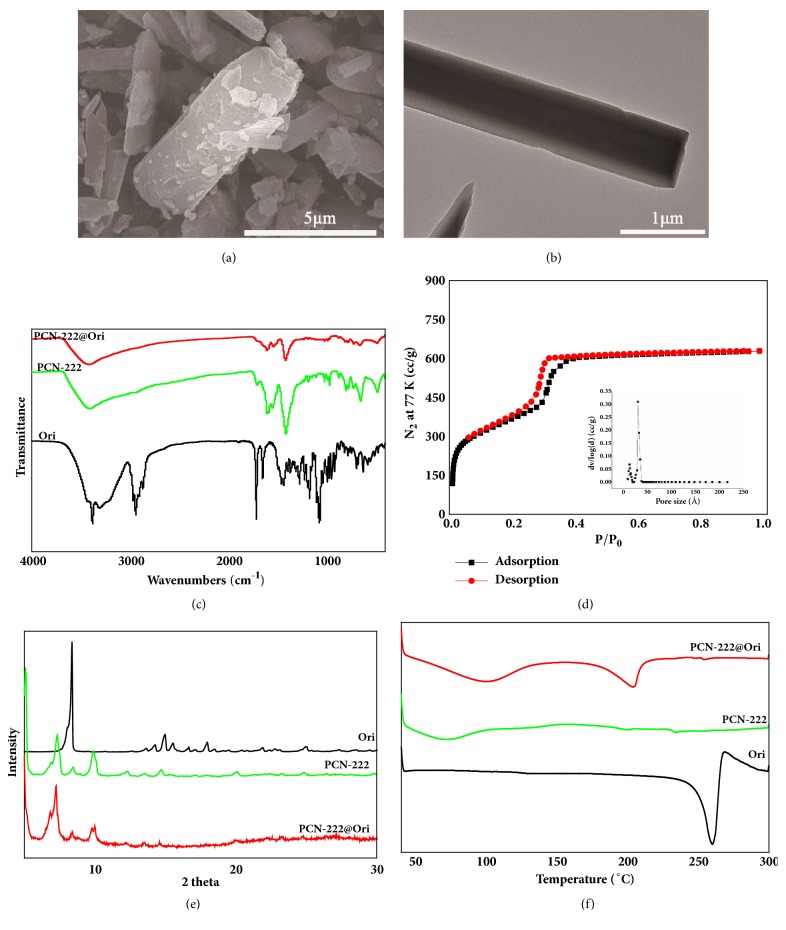

As large pore kind of Zr-MOF, PCN-222 can be synthesized in aqueous phase under mild conditions and is a promising candidate for encapsulating anticancer drugs. Dark violet rod-like crystals of PCN-222 were obtained via solvothermal reactions. SEM (Figure 2(a)) and TEM (Figure 2(b)) images indicated that PCN-222 had a diameter of approximately 5.27μm, and these NPs show a perfect drug loading capacity [53]. The XRD was performed to analyze the powder purity of PCN-222 at room temperature, and the main crystalline peaks are obvious at 5.24°, 7.24°, and 9.80°, which well agree with the simulated peak pattern (Figure 2(c)). The porous structure of PCN-222 was explored by N2 adsorption-desorption isothermals at 77 K. The typical type IV isotherm of PCN-222 exhibits a steep increase at the points of P/P0=0.05 and 0.3, respectively, suggesting that both micropore and mesopore existed in the MOF (Figure 2(d)). The BET specific surface area of PCN-222 was calculated to be 2476 m2/g and the pore volume was 1.53 cm3/g. The pore size distributions based on DTF method show that the pore size is 1.2 nm and 3.2 nm, respectively, similar to that reported in the previous literature [54]. The large specific surface area and pore volume of the sample provide the possibility for high loading of the drug. And the fluorescence of PCN-222 was determined at maximum excitation/emission wavelengths as well as 675/640nm (Figures 2(e) and 2(f)) indicating that the fluorescence of PCN-222 can avoid biological autofluorescence and has good tissue penetrability [55].

Figure 2.

Surface topography and structural analysis of PCN-222: (a) SEM, (b) TEM, (c) PXRD spectra, (d) the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K for PCN-222, (e) emission wavelength spectrum, and (f) excitation wavelength spectrum of PCN-222 (dispersion in high purity water).

3.2. Evaluation of Nanosafety of PCN-222 Designed for Drug Delivery

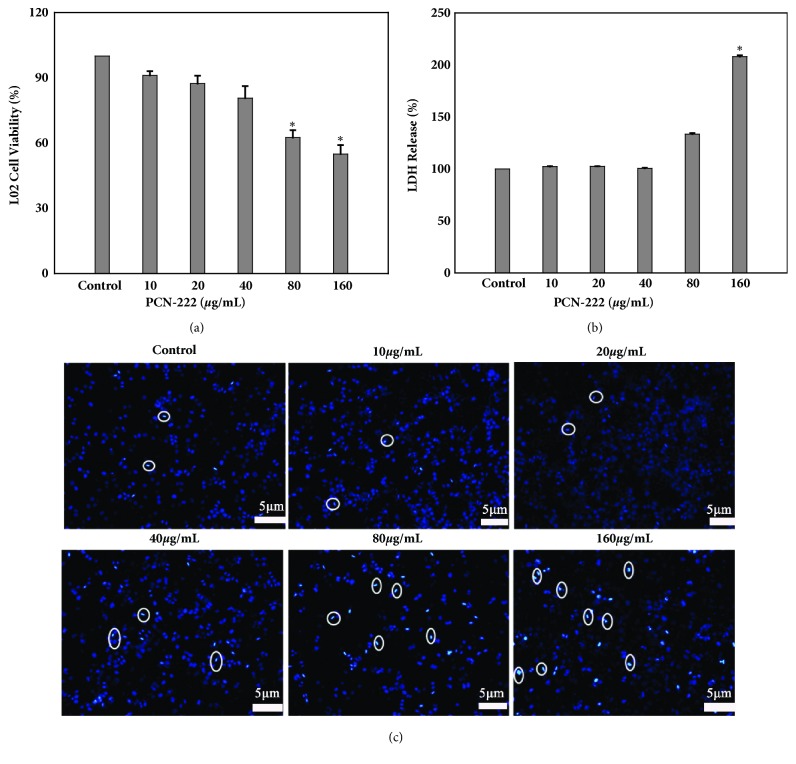

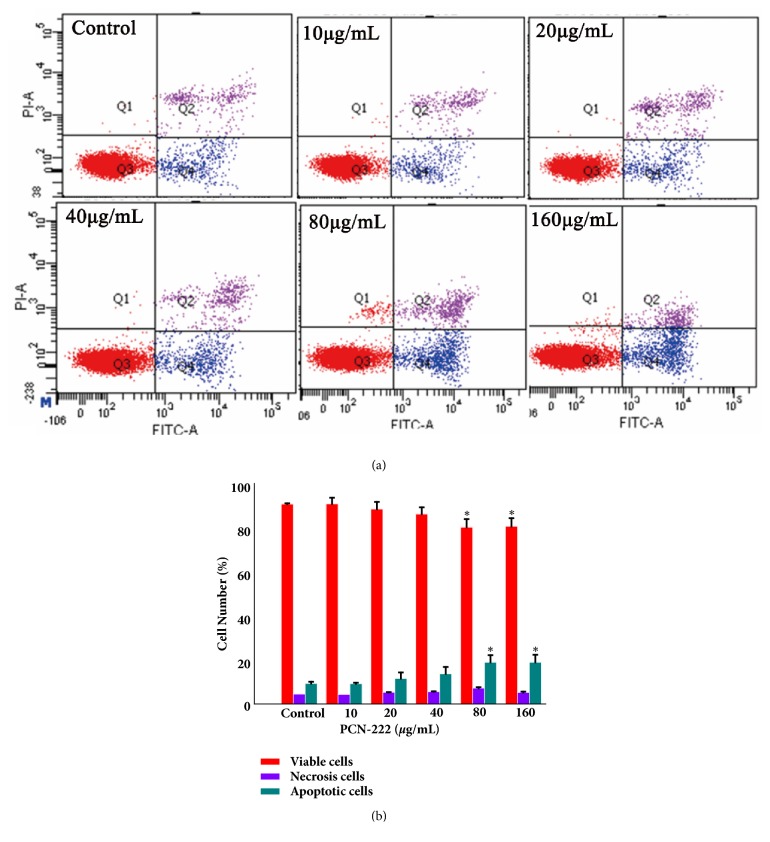

For the delivery of nanomaterials with large specific surface area, it easy to enter and deposit into the liver cells. The cytotoxicity of the PCN-222 in L02 cells was determined by the MTT assay. Cells were treated with different concentrations (0–160 μg/mL) for 48h, and the result (Figure 3(a)) showed that there was no significant (P>0.05) effect on L02 cell proliferation under 40 μg/mL when compared with vehicle controls indicating that the PCN-222 is less toxic toward L02 cells. Leakage of LDH is a sign of cell membrane damage. The results showed that leakage of LDH occurring in L02 cells have few effects after treatment with PCN-222 under concentration of 80 μg/mL (Figure 3(b)). DAPI staining (Figure 3(c)) observed that PCN-222 treated cells have suitable morphology with an intact nucleus and only at extremely high concentration may induce condensation of chromatin and nuclear fragmentation. In addition, following treatment with PCN-222 for 48 h, the percentage of viable cells had insignificantly changed below 40 μg/mL. Furthermore, the percentage of early apoptosis cells increased only from 4.80 % ± 0.56 to 13.63 % ± 2.16, and necrotic and late apoptotic cells almost do not increase as PCN-222 is increased (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). In short, PCN-222 might cause the cell apoptosis, damage cell membrane, and split nuclear under ultimate high concentration, but it has good biosafety and cell biocompatibility under 40 μg/mL. Those studies clearly indicate that PCN-222 are nontoxic toward the cell under 40 μg/mL.

Figure 3.

Effects of PCN-222 on cell viability and morphology. (a) MTT assay data were presented as mean ± SD of viability % of three independent experiments. (b) LDH assay was used to assess cell membrane damage and results were presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (∗p< 0.05 versus control). (c) L02 cells nuclear morphology was evaluated using DAPI staining (the circle markers represent the apoptotic cells).

Figure 4.

Effects of PCN-222 on apoptosis in L02 cells. (a) Flow cytometry detection of apoptosis with FITC-Annexin V/PI double staining. (b) The percentages of viable, early apoptosis, and necrosis cells of L02 cells after incubation with different concentrations of PCN-222 for 48 h. The data are expressed as means ± SD from three independent experiments (∗ p < 0.05 versus control).

3.3. Optimal Loading Process and Evaluation of PCN-222@Ori

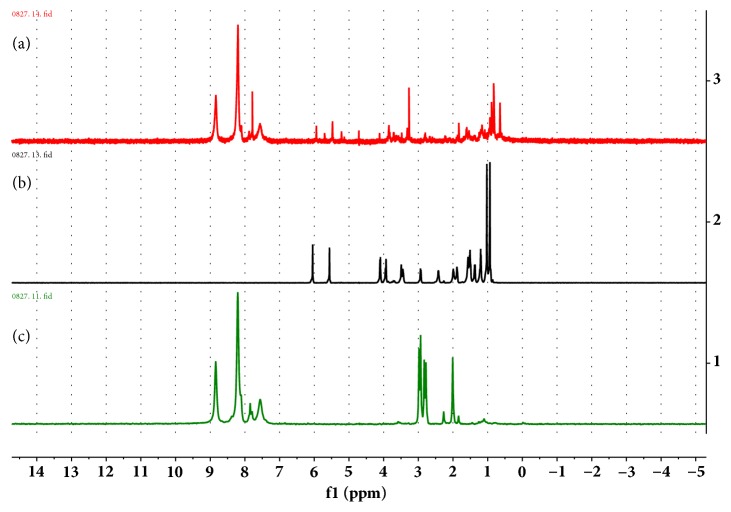

By using the L9(34) orthogonal table, three factors such as rate of Ori to PCN-222 (A), mixing time (B), and the amount of solvent (C) were selected to be optimized. The drug loading rate reached up to 38.77 wt%, under optimized conditions: PCN-222: Ori: Methanol (1: 3: 1), with magnetic stirring for 4 days. To further confirm the existence of the drug Ori in PCN-222@Ori, the 1H-NMR spectra of alkaline-digested PCN-222@Ori were analyzed in KOH/D2O solution, as shown in Figure 5(a). To identify the peak of the TCPP ligand and Ori molecule solution, the 1H-NMR spectra of the alkaline-digested PCN-222 and Ori in KOH/D2O solution were also provided in Figures 5(b) and 5(c). Obviously, the peak of Ori can be observed in alkaline-digested PCN-222@Ori solution. During drug loading, PCN-222 can preserve the original structure while Ori entered the void structure, shown in SEM (Figure 6(a)) and TEM (Figure 6(b)) images. The spectra of PCN-222@Ori were consistent with the spectra of PCN-222, shown in Figure 6(c). The intensity of the absorption peak and the small changes in the position indicate that there is some interaction between PCN-222 and Ori. To gauge the porosity of the PCN-222 following Ori installation, N2 adsorption-desorption experiments were conducted at 77 K; the obtained isotherms of PCN-222@Ori are shown in Figure 6(d). The BET specific surface area of PCN-222@Ori was calculated to be 1258 m2/g and the pore volume was 0.97 cm3/g. Both sets of isotherms indicate decrease of porosity following Ori introduction, and the pore size is 1.2 nm and 3.2 nm, respectively, by the pore size distribution plots. It is noteworthy that the BET specific surface area and the pore volume of PCN-222 are reduced, so the drug is loaded inside the MOF pore rather than sitting on the surface of the MOFs. From the result of X-ray diffraction pattern (Figure 6(e)) and DSC spectra (Figure 6(f)), the absorption peak of PCN-222@Ori completely disappeared after taking the drug, indicating that the Ori was distributed in PCN-222 with amorphous state.

Figure 5.

1H-NMR spectra of (a) alkaline-digested PCN-222@Ori, (b) alkaline-digested Ori, and (c) PCN-222 in KOH/D2O solution.

Figure 6.

Surface topography and structural analysis of PCN-222@Ori: (a) SEM, (b) TEM, (c) FTIR, (d) the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K, (e) XPRD, and (f) DSC.

3.4. pH-Responsive Release Profile

The pH value in tumor and inflammatory tissues tends to be more acidic (pH 6.0–7.0) than that in blood and healthy tissue (pH 7.4), just as was said by Valeria De Matteis [56]: this important factor may be used to design pH-responsive nanosystem targeted at tumor therapy. Thus, we can design nanocarriers that are sensitive to pH signals to trigger selective drug release in cancer cells. In this study, the Ori release profiles of PCN-222@Ori were explored at two different pH values (pH 7.2 and pH 5.5). And PCN-222@Ori at acidic condition (pH 5.5, 86.29%) showed a significantly higher drug release rate than those at the neutral condition (pH 7.2, 63.30%) in 168 h, as is shown in Figure 7. The releasing characteristic parameter was explored by different mathematical model to explain the mechanism of drugs release, and the fitting results are shown in Table 1. The result of the study on the mechanism of drug release showed that in vitro drug release was fitted to Weibull and mechanism of release was diffusion. The fitted equations at pH 5.5 and pH 7.2 are lnln(1/(1-Rt)) = 0.6384lnt – 2.4694 (R2=0.977) and lnln(1/(1-Rt)) = 0.653lnt-3.169 (R2=0.987), respectively.

Figure 7.

In vitro Ori release profiles of the PCN-222@Ori at different pH values. (a) The release curve and (b) the total amount of drug release.

Table 1.

Fitting curve by different mathematical model under different pH values (Rt: accumulated release rate).

| pH=5.5 | pH=7.2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation | r2 | Equation | r2 | |

| zero-order | Rt = 0.0047 t + 0.2433 | 0.811 | Rt = 0.0039t + 0.1298 | 0.850 |

| First-order | Ln(1-Rt) = -0.0118 t - 0.2627 | 0.944 | Ln(1-Rt) = - 0.0065t - 0.1379 | 0.897 |

| Higuchi | Rt = 0.0679 t1/2 +0.0874 | 0.952 | Rt= 0.055t1/2 + 0.0079 | 0.963 |

| Weibull | lnln[1/(1-Rt)] = 0.6384lnt - 2.4694 | 0.977 | lnln[1/(1-Rt)] = 0.653lnt - 3.1688 | 0.987 |

| Ritger-Peppas | ln (Rt/R∞) = 0.4862lnt - 2.4274 | 0.933 | ln (Rt/R∞) = 0.5608lnt - 3.1287 | 0.981 |

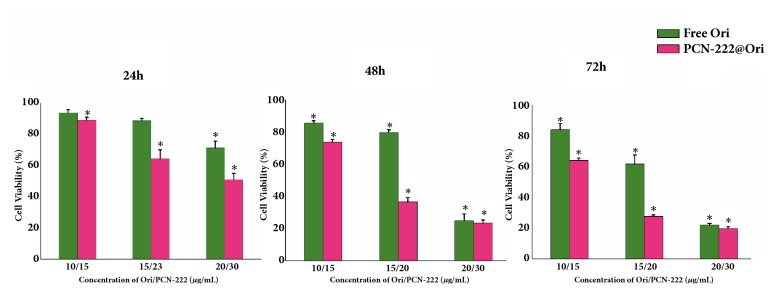

3.5. Cytotoxic Effect of PCN-222@Ori on HepG2 Cells

Free Ori and PCN-222@Ori were also investigated for the cancer therapy. PCN-222@Ori showed excellent therapeutic efficacy for HepG2 cells as the dosage increased with time prolonged, compared with free Ori. As is shown in Figure 8, after the treatment with free Ori at a concentration of 20 μg/mL for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, the cell viability fell from the baseline level to 71%, 25%, and 21%, and after the treatment with PCN-222@Ori, the cell viability decreased to about 51%, 23%, and 19% at the concentration of 20 μg/mL for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively. Toxicity of PCN-222@Ori was higher than that of free Ori as well as equal amount of Ori. It is indicated that PCN-222, which we synthesized, and Ori have potential synergistic effect. It is noteworthy that PCN-222 was safe for L02 cells at high anticancer activity. In summary, PCN-222 has been developed as a pH-responsive nanosystem for drug delivery in the cancer therapy.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the antitumor activity of PCN-222@Ori and free Ori by incubating various concentrations of samples for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h with HepG2 cells.

4. Conclusions

The inorganic cluster of PCN-222 (Zr6(μ-OH)8(OH)8(CO2)8) can provide high density of hydroxyl groups, which can bind with Ori molecules via H-bonds interaction, and it owns two types of 1-D channels which provide sufficient space for loading Ori [57]. The isoelectric point pHpzc of PCN-222 is at 7.0-8.0 [58], so the force of H-bonds between PCN-222 and Ori decreases under acidic conditions (Ph 5.5), which is the reason why the release rate of PCN-222 under acidic conditions is faster than that under neutral conditions.

In summary, we have successfully fabricated a PCN-222, which can be used as an ideal drug delivery system. Frameworks with high surface area and suitable pore size are good candidates for Ori loading. What is more, it provides opportunity to reduce the adverse effects of Ori because the system showed a release mechanism. Low cytotoxic activity, efficient drug loading capacity (about 38.77 wt %), and controlled release with a Weibull distribution drug release under different pH values of PCN-222 prove its practical value as a drug carrier. In particular, the pH-responsive release of material confirms the potential applications of PCN-222 as smart drug carriers.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81703715, 21536001, and 21606007); the Training Programme Foundation for the Beijing Municipal Excellent Talents (No. 2017000020124G295); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Scientific Research Project for Distinguished Young Scholar (No. 2018-JYBXJQ005). The test was assisted by BioNMR Facility, Tsinghua University, Branch of China, National Center for Protein Sciences (Beijing).

Contributor Information

Hongliang Huang, Email: huanghl@mail.buct.edu.cn.

Xingbin Yin, Email: yxbtcm@163.com.

Jian Ni, Email: njtcm@263.net.

Data Availability

The original data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Xin Leng, Xingbin Yin, and Jian Ni designed the research. Xin Leng, Longtai You, and Wenping Wang performed the experiments. Hongliang Huang and Na Sai conducted the data analyses. Leng Xin wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wei L.-Q., Li Y., Mao L.-Y., Chen Q., Lin N. A series of porous metal-organic frameworks with hendecahedron cage: Structural variation and drug slow release properties. Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 2018;257:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pham T., Forrest K. A., Franz D. M., Space B. Experimental and theoretical investigations of the gas adsorption sites in rht-metal-organic frameworks. CrystEngComm. 2017;19(32):4646–4665. doi: 10.1039/C7CE01032J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L.-D., Zheng Y.-Q., Zhu H.-L. Manganese oxides derived from Mn(II)-based metal-organic framework as supercapacitor electrode materials. Journal of Materials Science. 2018;53(2):1346–1355. doi: 10.1007/s10853-017-1575-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nazari M., Martinez M.-R., Babarao R., et al. Aqueous contaminant detection via UiO-66 thin film optical fiber sensor platform with fast Fourier transform based spectrum analysis. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2018;51025601 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakuru V. R., Kalidindi S. B. Synergistic Hydrogenation over Palladium through the Assembly of MIL-101 (Fe) MOF over Palladium Nanocubes. Chemistry - A European Journal. 2017;23(65):16456–16459. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudd N.-D., Wang H., Fuentes-Fernandez E.-M., et al. Previous Article Next Article Table of ContentsHighly Efficient Luminescent Metal-Organic Framework for the Simultaneous Detection and Removal of Heavy Metals from Water. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2016;8:30294–30303. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b10890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J.-X., Yan B. Eu(III)-functionalized In-MOF (In(OH)bpydc) as fluorescent probe for highly selectively sensing organic small molecules and anions especially for CHCl3 and MnO4. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2017;504:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang L., Wang X.-H., Sun Y., et al. Magnetic solid-phase extraction of triazine herbicides from rice using metal-organic framework MIL-101(Cr) functionalized magnetic particles. Talanta. 2018;179:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rojas S., Devic T., Horcajada P. Metal organic frameworks based on bioactive components. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2017;5:2560–2573. doi: 10.1039/c6tb03217f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haydar M.-A., Abid H.-R., Sunderland B., Wang S. Metal organic frameworks as a drug delivery system for flurbiprofen. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2017;11:2685–2695. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S145716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu M.-X., Yang Y.-W. Metal–Organic Framework (MOF)‐Based Drug/Cargo Delivery and Cancer Therapy. Advanced Materials. 2017;29(23) doi: 10.1002/adma.201606134.1606134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X., Fan R., Qiang L., et al. Controlled Zn2+-Triggered Drug Release by Preferred Coordination of Open Active Sites within Functionalization Indium Metal Organic Frameworks. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2017;11(7) doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b09227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock N., Biswas S. Synthesis of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): routes to various MOF topologies, morphologies, and composites. Chemical Reviews. 2012;112(2):933–969. doi: 10.1021/cr200304e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H., Jiang W., Liu R., Zhang J., Zhang D. Rational Design of Metal Organic Framework Nanocarrier-Based Codelivery System of Doxorubicin Hydrochloride/Verapamil Hydrochloride for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance with Efficient Targeted Cancer Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2017;9(23):19687–19697. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b05142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bag P.-P., Wang D., Chen Z., Cao R. Outstanding drug loading capacity by water stable microporous MOF: a potential drug carrier. Chemical Communications. 2016;52:3669–3672. doi: 10.1039/C5CC09925K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohamed N. A., Davies R. P., Lickiss P. D., et al. Chemical and biological assessment of metal organic frameworks (MOFs) in pulmonary cells and in an acute in vivo model: relevance to pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy. Pulmonary Circulation. 2017;7(3):643–653. doi: 10.1177/2045893217710224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang K., Zhang L., Hu Q., et al. Thermal Stimuli‐Triggered Drug Release from a Biocompatible Porous Metal-Organic Framework. Chemistry - A European Journal. 2017;23(42):10215–10221. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H., Wei J., Liu R., et al. Rational Design of MOF Nanocarrier-Based Co-Delivery System of Doxorubicin Hydrochloride/Verapamil Hydrochloride for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance with Efficient Targeted Cancer Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2017;9:19687–19697. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b05142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia X., Yang Z., Wang Y., et al. Hollow Mesoporous Silica@Metal–Organic Framework and Applications for pH-Responsive Drug Delivery. ChemMedChem. 2018;13(5):400–405. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201800019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abazari R., Reza A.-M., Slawin A., Cameron L., Warren C. Morphology- and size-controlled synthesis of a metal-organic framework under ultrasound irradiation: An efficient carrier for pH responsive release of anti-cancer drugs and their applicability for adsorption of amoxicillin from aqueous solution. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2018;42:594–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin W., Hu Q., Jiang K., Cui Y.-J., Yang Y., Qian G.-D. A porous Zn-based metal-organic framework for pH and temperature dual-responsive controlled drug release. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2017;249:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bůžek D., Zelenka J., Ulbrich P., et al. Nanoscaled porphyrinic metal-organic frameworks: photosensitizer delivery systems for photodynamic therapy. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2017;5(9):1815–1821. doi: 10.1039/C6TB03230C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartlieb K. J., Ferris D. P., Holcroft J. M., et al. Encapsulation of Ibuprofen in CD-MOF and Related Bioavailability Studies. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2017;14(5):1831–1839. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad N., Younus H.-A., Chughtai A.-H., et al. Development of Mixed metal Metal-organic polyhedra networks, colloids, and MOFs and their Pharmacokinetic applications. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:p. 832. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00733-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C.-Y., Qin C., Wang X.-L., Su Z.-M. Metal-organic frameworks as potential drug delivery systems. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2013;10(1):89–101. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.741583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocca J.-D., Liu D., Lin W.-B. Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Imaging and Drug Delivery. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2011;44:957–968. doi: 10.1021/ar200028a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang F.-M., Dong H., Zhang X., et al. Postsynthetic Modification of ZIF-90 for Potential Targeted Codelivery of Two Anticancer Drugs. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2017;9(32):27332–27337. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b08451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim M., Sabouni R., Husseini G. A. Anti-cancer Drug Delivery Using Metal Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2017;24:193–214. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160926151216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan S., Qin J.-S., Zou L., Chen Y.-P., Wang X., Zhang Q. Thermodynamically Guided Synthesis of Mixed-Linker Zr-MOFs with Enhanced Tunability. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:6636–6642. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y., Sun L., Feng D., Zhou H.-C. An In Situ One‐Pot Synthetic Approach towards Multivariate Zirconium MOFs. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2016;55(22):6471–6475. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng D., Gu Z.-Y., Li J.-R., Jiang H.-L., Wei Z., Zhou H.-C. Zirconium-metalloporphyrin PCN-222: mesoporous metal-organic frameworks with ultrahigh stability as biomimetic catalysts. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2012;124:10453–10456. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang G.-Y., Zhuang Y.-H., Dan S., Su G.-F., Cosnier S., Zhang X. Zirconium-Based Porphyrinic Metal-Organic Framework (PCN-222): Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Response and Its Application for Label-Free Phosphoprotein Detection. Analytical Chemistry. 2016;88(22):11207–11212. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J., Chen X., Li Y., Zhuang Q., Liu P., Gu J. Zr-Based MOFs Shielded with Phospholipid Bilayers: Improved Biostability and Cell Uptake for Biological Applications. Chemistry of Materials. 2017;29:4580–4589. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b01329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian L., Xie K., Sheng D., Wan X., Zhu G. Antiangiogenic effects of oridonin. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17:p. 192. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1706-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng Y., Chen C., Yu H., et al. Oridonin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury in mice via inhibition of apoptosis. American Journal of Translational Research. 2017;9(9):4271–4279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao J., Zhang M., He P., et al. Proteomic analysis of oridonin-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2017;15:1807–1815. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi Q., Zhang P., Li Q.-X., Pan Q., Zheng H.-L., Zhao S.-R. Effect of oridonin on apoptosis and intracellular reactive oxygen species level in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2017;42(12):2361–2365. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.2017.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia S.-X., Zhang X.-L., Li C.-H., Guan H.-L. Oridonin inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis through blocking the Notch signaling. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2017;25(4):638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu T., Jin F., Wu K.-R., Ye Z.-P., Li N. Oridonin enhances in vitro anticancer effects of lentinan in SMMC-7721 human hepatoma cells through apoptotic genes. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2017;14(5):5129–5134. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu J., Chen X., Qu S., et al. Oridonin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in hormone-independent prostate cancer cells. Oncology Letters. 2017;13(4):2838–2846. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J., Ren X., Zhang L., Li Y., Cheng B., Xia J. Oridonin inhibits oral cancer growth and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;100:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Y., Sun Y., Zhu J., et al. Oridonin exerts anticancer effect on osteosarcoma by activating PPAR-γ and inhibiting Nrf2 pathway. Cell Death & Disease. 2018;9:p. 15. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0031-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li D., Han T., Liao J., et al. Oridonin, a Promising ent-Kaurane Diterpenoid Lead Compound. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17(9):p. 1395. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He Z., Xiao X., Li S., et al. Oridonin induces apoptosis and reverses drug resistance in cisplatin resistant human gastric cancer cells. Oncology Letters. 2017;14(2):2499–2504. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y., Liu X.-Q., Liu G.-P., et al. Novel galactosylated biodegradable nanoparticles for hepatocyte-delivery of oridonin. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2016;502(1-2):47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng D.-D., Duan G.-X., Zhang D.-R., et al. Galactosylated chitosan nanoparticles for hepatocyte-targeted delivery of oridonin. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2012;436(1-2):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X.-W., Zhang T., Lan Y., Wu B., Shi Z. Nanosuspensions Containing Oridonin/HP-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes for Oral Bioavailability Enhancement via Improved Dissolution and Permeability. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2016;17(2):400–408. doi: 10.1208/s12249-015-0363-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu L., Li M., Liu X., Du L., Jin Y. Inhalable oridonin-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic)acid large porous microparticles for in situ treatment of primary non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2017;7(1):80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Z.-Y., Li Y.-J., Shi P., Wang B.-C., Huang X.-Y. Functionalized graphene oxide as a nanocarrier for loading and delivering of oridonin. Chinese Journal Of Organic Chemistry. 2013;33(03):573–580. doi: 10.6023/cjoc201211033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bugnicourt L., Ladavière C. A close collaboration of chitosan with lipid colloidal carriers for drug delivery applications. Journal of Controlled Release. 2017;256:121–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mondal J., Das J., Shah R., Khuda-Bukhsh A. R. A homeopathic nosode, Hepatitis C 30 demonstrates anticancer effect against liver cancer cells in vitro by modulating telomerase and topoisomerase II activities as also by promoting apoptosis via intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2016;14(3):209–218. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(16)60251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zang Q.-Q., Zhang L., Gao N. Ophiopogonin D inhibits cell proliferation, causes cell cycle arrest at G2/M, and induces apoptosis in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2016;14(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(16)60238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin S., Liu X., Tan L., et al. Porous Iron-Carboxylate Metal-Organic Framework: A Novel Bioplatform with Sustained Antibacterial Efficacy and Nontoxicity. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2017;9(22):19248–19257. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b04810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng D.-W., Gu Z.-Y., Li J.-R., Jiang H.-L., Wei Z., Zhou H.-C. Zirconium-metalloporphyrin PCN-222: mesoporous metal-organic frameworks with ultrahigh stability as biomimetic catalysts. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 2012;51:10307–10310. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weissleder R. A clearer vision for in vivo imaging. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:316–317. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matteis V.-D., Rizzello L., Bello M. P.-D., Rinaldi R. One-step synthesis, toxicity assessment and degradation in tumoral pH environment of SiO2@Ag core/shell nanoparticles. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2017;19:p. 196. doi: 10.1007/s11051-017-3870-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang B., Lv X.-L., Xie L.-H., et al. Highly Stable Zr(IV)-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for the Detection and Removal of Antibiotics and Organic Explosives in Water. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:6204–6216. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao X., Zhao H., Dai W., et al. A metal-organic framework with large 1-D channels and rich OH sites for high-efficiency chloramphenicol removal from water. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2018;526:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.