Abstract

Objectives:

Given public health’s emphasis on health disparities in underrepresented racial/ethnic minority communities, having a racially and ethnically diverse faculty is important to ensure adequate public health training. We examined trends in the number of underrepresented racial/ethnic minority (ie, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander) doctoral graduates from public health fields and determined the proportion of persons from underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups who entered academia.

Methods:

We analyzed repeated cross-sectional data from restricted files collected by the National Science Foundation on doctoral graduates from US institutions during 2003-2015. Our dependent variables were the number of all underrepresented racial/ethnic minority public health doctoral recipients and underrepresented racial/ethnic minority graduates who had accepted academic positions. Using logistic regression models and adjusted odds ratios (aORs), we examined correlates of these variables over time, controlling for all independent variables (eg, gender, age, relationship status, number of dependents).

Results:

The percentage of underrepresented racial/ethnic minority doctoral graduates increased from 15.4% (91 of 592) in 2003 to 23.4% (296 of 1264) in 2015, with the largest increase occurring among black graduates (from 6.6% in 2003 to 14.1% in 2015). Black graduates (310 of 1241, 25.0%) were significantly less likely than white graduates (2258 of 5913, 38.2%) and, frequently, less likely than graduates from other underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups to indicate having accepted an academic position (all P < .001).

Conclusions:

Stakeholders should consider targeted programs to increase the number of racial/ethnic minority faculty members in academic public health fields.

Keywords: underrepresented minorities, doctoral education, race, ethnicity, academic careers

Public health is a multidisciplinary field concerned with promoting and protecting the health of populations and communities, especially racial/ethnic minority populations who are at an increased risk for many illnesses and injuries.1–3 Underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups include black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander persons. Given public health’s emphasis on health disparities in underrepresented racial/ethnic minority communities, the recruitment and retention of racially and ethnically diverse faculty members in schools and programs of public health is a fundamental component to ensure adequate public health training at all levels.

Research conducted in education and other health professions found that underrepresented racial/ethnic minority faculty are more likely than their white counterparts to conduct research on health disparities4; promote and advocate for an understanding of cultural issues, sensitivities, and practices5; and provide mentoring for other racial/ethnic minority students, who are vital future contributors to the public health workforce.6 As the public health workforce ages and retires, leading to an anticipated shortage of 250 000 workers by 2020,7 schools and programs of public health are increasing the number of trainees at the undergraduate, masters, and doctoral levels.8,9 An increase in the number of doctoral trainees may help with the recruitment of new faculty members as schools and programs of public health keep up with increasing demand.

Although underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups comprised more than 30% of the US population in 2015,10 they constituted a disproportionately smaller proportion of doctoral graduates (18.5%)11 and academic faculty in public health disciplines (7.6%) in 2013,12 resulting in a shortage of underrepresented faculty members in schools and programs of public health.13 Researchers have commented that current university settings are not optimal for the recruitment or retention of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates, in part because minority faculty members have higher mentoring and service responsibilities than their white counterparts.13,14 Although commentaries and studies help to characterize the problems, they fail to provide empirical evidence for solutions to address the lack of underrepresented minority professionals on the faculties of schools and programs of public health. For example, it is unclear whether the number of underrepresented minority graduates from public health doctoral programs is insufficient to fill faculty positions or whether these graduates are not choosing to work in academic settings. A better understanding of the trends among underrepresented minority graduates receiving public health doctoral degrees is an important first step in addressing this issue.

The primary objective of this study was to examine trends over time in the number of underrepresented racial/ethnic minority doctoral graduates from the core knowledge areas of public health: biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health services administration, and social and behavioral sciences. A secondary objective was to quantify the proportion of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates in academia and determine whether these rates have changed over time. We examined demographic and university characteristics as well as the public health knowledge areas that are associated with underrepresented racial/ethnic minority graduates who had accepted academic positions and those who had not.

Methods

We analyzed restricted data from the National Science Foundation (NSF) Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED). We analyzed pooled cross-sectional data from respondents who earned research doctoral degrees from US institutions from 2003 through 2015. The NSF collects data annually on more than 50 000 research doctoral graduates in all fields of study at or around the time of graduation.15 The inclusion criterion for research doctorates as defined by the NSF was completion of an original intellectual contribution, traditionally in the form of a dissertation. Our data include graduates with doctor of philosophy (PhD) degrees, doctor of science (ScD) degrees, and doctor of public health (DrPH) degrees (ie, DrPH graduates who complete a dissertation). Each university decides which terminal degree is classified as a research doctorate; however, professional degrees, such as doctor of medicine, juris doctor, and some DrPH degrees, are not included in the data. In addition to basic demographic information, the survey collects data on graduates’ demographic characteristics and degree field, characteristics of the degree-granting institutions, and graduates’ postgraduation plans.15 The Indiana University Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt.

For our main variable of interest, we used the NSF’s definition of racial/ethnic underrepresented minority in US health sciences, which includes black, Hispanic, and indigenous American persons. In our analysis, we used “black” to describe all persons who self-selected black or African American race, and we used “Hispanic” to describe all persons who selected Mexican or Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic or Latina/o categories regardless of their racial designation. Because of small sample sizes, the race category “other underrepresented minority” included persons who self-selected American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, or ≥2 races, one of which was an aforementioned underrepresented minority.

A secondary variable of interest was the number of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates who, at the time of the survey (ie, approximately the time of graduation), had accepted an academic position. We derived this variable from the SED, and it included any position, including postdoctoral fellowships, that was in an institution of higher education.

Our independent variables were various individual and institutional characteristics. Individual characteristics were race, sex, age, marriage or marriage-like relationship, number of dependents aged <18, whether a US citizen, whether a graduate of a historically black college or university, type of institution attended (public or private), receipt of full tuition remission, knowledge area, and year of graduation. Institutional characteristics were university type (public, private nonprofit, or private for profit) and the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. This classification system is a framework that assigns institutions that confer doctoral degrees into the following categories based on measures of research activity: highest research activity (R1), higher research activity (R2), moderate research activity (R3), and other special focus and tribal colleges.16 On the SED, respondents identify their field of study from a list of 331 academic codes.15 We included graduates who selected a discrete code for biostatistics, environmental health sciences, or epidemiology. Because the SED did not include discrete codes for health services administration, we conflated graduates who selected either “health policy analysis” or “health systems/service administration” into a “health services administration” category. In addition, social behavioral sciences did not receive a discrete code until 2015. We assumed that participants who received doctoral degrees in social behavioral sciences before 2015 selected “public health general” as their field of study. As a result, we conflated respondents in 2015 who selected social behavioral sciences with all years of “public health general,” which we referred to as “general public health.”

We calculated descriptive statistics to examine trends in the number of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates in each knowledge area. We used the Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact tests to examine differences in the number of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates by race among the independent variables. We also used 2 logistic regression models to examine the associations between independent variables and 2 dependent variables. The dependent variables in our models included the rate of underrepresented minority graduates (model 1) and the rate of underrepresented minority graduates who accepted employment in academia (model 2). In both models, we determined the adjusted odds of being in each of our dependent variables, controlling for gender, age, married or in a marriage-like relationship, number of dependent offspring, US citizenship status, public health knowledge areas, Carnegie classification of the degree-granting institution, whether tuition remission was provided during doctoral studies, type of university from which the degree was granted, and the year of graduation. We conducted all analyses using SPSS version 24.0.17 We considered P < .05 to be significant.

Results

Overall, 11 771 persons received a doctoral degree in 1 of the public health knowledge areas from 2003 through 2015 (Table 1). Most of the 11 771 doctoral degree recipients were female (n = 7879, 66.9%), were US citizens (n = 8028, 68.2%), were white (n = 5913, 50.2%), were married or in a marriage-like relationship (n = 7089, 60.2%), and had received their degree from an R1 university (n = 9478, 81.3%). The most common public health knowledge areas were general public health (n = 4248, 36.1%), epidemiology (n = 3806, 32.3%), and biostatistics (n = 1696, 14.4%), and the least common knowledge areas were health services administration (n = 1209, 10.3%) and environmental health (n = 812, 6.9%). Eighty-three (0.7%) graduates received a doctoral degree from a historically black college or university. The total number of public health doctoral recipients increased during the study period, from 631 in 2003 to 1348 in 2015.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of doctoral graduates and their academic institutions in public health core knowledge areas, United States, 2003-2015 (n = 11 771)a

| Characteristic | Graduates, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Female sex | 7879 (66.9) |

| Mean age (SD), y | 37 (8.0) |

| Race/ethnicityb | |

| White | 5913 (50.2) |

| Asian | 2887 (24.5) |

| Underrepresented minority | 2170 (18.4) |

| Black | 1241 (10.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 576 (4.9) |

| Other | 353 (3.0) |

| Nonresponse | 801 (6.8) |

| Married or in a marriage-like relationship | 7089 (60.2) |

| Carnegie classificationc,d | |

| Highest research activity (R1) | 9478 (81.3) |

| Higher research activity (R2) | 591 (5.1) |

| Moderate research activity (R3) | 791 (6.8) |

| Other | 798 (6.8) |

| Type of university granting the degreec | |

| Public | 7192 (61.5) |

| Private nonprofit | 3846 (32.9) |

| Private for profit | 646 (5.5) |

| Number of dependents aged <18 yc | |

| 0 | 6780 (64.6) |

| 1 | 1867 (15.9) |

| 2 | 1382 (13.2) |

| ≥3 | 474 (4.5) |

| US citizen | 8028 (68.2) |

| HBCU graduate | 83 (0.7) |

| Received full tuition remission while a doctoral student | 4235 (36.0) |

| Knowledge aread | |

| Biostatistics | 1696 (14.4) |

| Environmental health | 812 (6.9) |

| Epidemiology | 3806 (32.3) |

| General public health | 4248 (36.1) |

| Health services administration | 1209 (10.3) |

| Year of graduation | |

| 2003 | 631 (5.4) |

| 2004 | 699 (5.9) |

| 2005 | 749 (6.4) |

| 2006 | 777 (6.6) |

| 2007 | 864 (7.3) |

| 2008 | 795 (6.8) |

| 2009 | 799 (6.8) |

| 2010 | 887 (7.5) |

| 2011 | 857 (7.3) |

| 2012 | 1047 (8.9) |

| 2013 | 1157 (9.8) |

| 2014 | 1161 (9.9) |

| 2015 | 1348 (11.5) |

Abbreviation: HBCU, historically black college and university.

aData source: National Science Foundation.15

bGraduates who reported that they were Hispanic were assigned to the appropriate Hispanic category, regardless of racial designation. Hispanic/Latino includes all persons who selected Mexican or Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic or Latino/a. Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Indigenous groups, and ≥2 racial backgrounds. Underrepresented minority includes black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and ≥2 races.

cSome participants did not provide this information. Percentages were calculated based on graduates who provided this information at the time of survey completion.

dThe Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education assigns institutions that confer doctoral degrees into 3 categories based on measures of research activity. Other refers to schools that did not receive 1 of these 3 designations because they had been identified as a tribal college or special focus institution.16

eThe core knowledge areas of public health are biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health services administration, and social and behavioral sciences. Social and behavioral sciences is included in general public health.

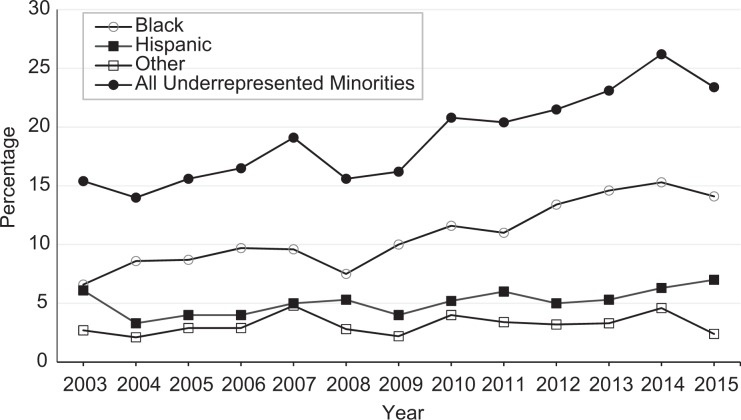

Doctoral degree recipients from underrepresented minority groups included 1241 (11.3%) black persons, 576 (5.3%) Hispanic persons, and 353 (3.2%) persons from other underrepresented minority groups (Table 2). Asian persons constituted 2887 (26.3%) doctoral degree graduates during the study period. Graduates from underrepresented minority groups constituted a larger proportion of doctoral degree recipients over time, from 91 of 592 (15.4%) graduates in 2003 to 296 of 1264 (23.4%) graduates in 2015 (Figure). Most of the increase in the proportion of underrepresented minority doctoral degree graduates was among black persons, who represented 6.6% (39 of 592) of all doctoral graduates in 2003 and 14.1% (178 of 1264) of all doctoral graduates in 2015. The proportion of growth among Hispanic doctoral graduates was more modest, increasing from 36 of 592 (6.1%) graduates in 2003 to 88 of 1264 (7.0%) graduates in 2015. Other underrepresented minority groups constituted approximately 2.5% of all doctoral graduates in any given year.

Table 2.

Public health doctoral recipients who reported having accepted an academic position at the time of the survey, by race and public health knowledge area, United States, 2003-2015 (n = 3737)a

| Years of Survey | Graduates Who Had Accepted an Academic Position, No. (%) | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Otherb | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biostatistics | |||||||

| 2003-2007 | 217/540 (40.2) | 88/198 (44.4) | 3/13 (23.1) | 5/11 (45.5) | 117/286 (40.9) | 3/11 (27.3) | <.001 |

| 2008-2011 | 192/501 (38.3) | 85/157 (54.1) | 6/17 (35.3) | 11/18 (61.1) | 88/271 (32.5) | 2/9 (22.2) | <.001 |

| 2012-2015 | 192/655 (29.3) | 82/194 (42.3) | 6/19 (31.6) | 4/9 (44.4) | 98/384 (25.5) | 2/11 (18.2) | <.001 |

| Total | 602/1696 (35.5) | 255/549 (46.4) | 15/49 (30.6) | 20/38 (52.6) | 303/941 (32.2) | 7/31 (22.6) | <.001 |

| Environmental health | |||||||

| 2003-2007 | 75/284 (26.4) | 45/153 (29.4) | 2/12 (16.7) | 2/9 (22.2) | 26/68 (38.2) | 0/10 (0) | .03 |

| 2008-2011 | 70/233 (30.0) | 40/110 (36.4) | 5/13 (38.5) | 5/11 (45.5) | 17/58 (29.3) | 2/2 (100.0) | .09 |

| 2012-2015 | 85/295 (28.8) | 46/140 (32.9) | 7/24 (29.2) | 4/17 (23.5) | 22/68 (32.4) | 5/10 (50.0) | .15 |

| Total | 230/812 (28.3) | 131/403 (32.5) | 14/49 (28.6) | 11/37 (29.7) | 65/194 (33.5) | 7/22 (31.8) | .31 |

| Epidemiology | |||||||

| 2003-2007 | 450/1199 (37.5) | 316/736 (42.9) | 23/68 (33.8) | 18/59 (30.5) | 75/236 (31.8) | 14/37 (37.8) | <.001 |

| 2008-2011 | 407/1216 (33.5) | 276/713 (38.7) | 25/83 (30.1) | 20/57 (35.1) | 74/247 (30.0) | 12/38 (31.6) | <.001 |

| 2012-2015 | 401/1391 (28.8) | 248/753 (32.9) | 29/121 (24.0) | 27/82 (32.9) | 68/280 (24.3) | 25/52 (48.1) | <.001 |

| Total | 1258/3806 (33.1) | 840/2202 (38.1) | 77/272 (28.3) | 65/198 (32.8) | 217/763 (28.4) | 51/127 (40.2) | <.001 |

| General public health | |||||||

| 2003-2007 | 479/1328 (36.1) | 303/713 (42.5) | 53/179 (29.6) | 23/72 (31.9) | 82/269 (30.5) | 16/44 (36.4) | <.001 |

| 2008-2011 | 359/1089 (33.0) | 223/577 (38.6) | 50/166 (30.1) | 25/66 (37.9) | 46/154 (29.9) | 15/40 (37.5) | <.001 |

| 2012-2015 | 504/1831 (27.5) | 300/866 (34.6) | 67/398 (16.8) | 35/130 (26.9) | 78/260 (30.0) | 22/64 (34.4) | <.001 |

| Total | 1342/4248 (31.6) | 826/2156 (38.3) | 170/743 (22.9) | 83/268 (31.0) | 206/683 (30.2) | 53/148 (35.8) | <.001 |

| Health services administration | |||||||

| 2003-2007 | 107/369 (29.0) | 69/178 (38.8) | 7/34 (20.6) | 0/6 (0) | 29/118 (24.6) | 0/9 (0) | .02 |

| 2008-2011 | 87/299 (29.1) | 52/142 (36.6) | 10/31 (32.3) | 2/7 (28.6) | 22/84 (26.2) | 1/8 (12.5) | .38 |

| 2012-2015 | 129/541 (23.8) | 85/283 (30.0) | 17/63 (27.0) | 4/22 (18.2) | 21/104 (20.2) | 2/8 (25.0) | .02 |

| Total | 323/1209 (26.7) | 206/603 (34.2) | 34/128 (26.6) | 6/35 (17.1) | 72/306 (23.5) | 3/25 (12.0) | .004 |

| Total | 3737/11 771 (31.7 | 2258/5913 (38.2) | 310/1241 (25.0) | 185/576 (32.1) | 863/2887 (29.9) | 121/353 (34.3) | <.001 |

aData source: National Science Foundation.15

bHispanic/Latino includes all persons who selected Mexican or Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic or Latino/a. Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Indigenous groups, and ≥2 racial backgrounds. Some participants did not report their race. Percentages were calculated based on persons who provided this information at the time of survey completion.

c P values were determined by using the Pearson χ2 test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Figure.

Proportion of underrepresented minority doctoral recipients (n = 2170) among all public health doctoral recipients, by year, United States, 2003-2015. Hispanic/Latino includes all persons who selected Mexican or Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic or Latino/a. Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Indigenous groups, and ≥2 racial backgrounds. Underrepresented minority includes black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and ≥2 races.

Data source: National Science Foundation.15

During the study period, 118 of 1608 (7.0%) graduates in biostatistics (P < .001), 108 of 705 (15.3%) graduates in environmental health (P < .001), 597 of 3562 (16.8%) graduates in epidemiology (P < .001), and 188 of 1097 (17.1%) graduates in health services administration (P = .006) were significantly less likely than all other doctoral graduates (2170 of 10 970; 19.8%) to be from underrepresented minority groups. Compared with all other doctoral graduates, doctoral graduates in general public health (1159 of 3998, 29.0%) were significantly more likely to be from an underrepresented minority group (P < .001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Underrepresented racial/ethnic minority doctoral recipients, by race and public health knowledge areas, United States, 2003-2015a

| Public Health Knowledge Area | Total No. of Graduates | No. (%) [P Valueb] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Underrepresented Minority Groups | Black | Hispanicc | Other Underrepresented Minority Groups | ||

| Total | 10 970 | 2170 (19.8) | 1241 (11.3) | 576 (5.3) | 353 (3.2) |

| Biostatistics | 1608 | 118 (7.3) [<.001] | 49 (3.0) [<.001] | 38 (2.4) [<.001] | 31 (1.9) [.002] |

| Environmental health | 705 | 108 (15.3) [<.001] | 49 (7.0) [<.001] | 37 (5.2) [.99] | 22 (3.1) [.88] |

| Epidemiology | 3562 | 597 (16.8) [<.001] | 272 (7.6) [<.001] | 198 (5.6) [.32] | 127 (3.6) [.16] |

| General public health | 3998 | 1159 (27.3) [<.001] | 743 (18.6) [<.001] | 268 (6.7) [<.001] | 148 (3.7) [.03] |

| Health services administration | 1097 | 188 (17.1) [.006] | 128 (11.7) [.70] | 35 (3.2) [<.001] | 25 (2.3) [.06] |

aData source: National Science Foundation.15

b P values were determined by using the Pearson χ2 test. P < .05 was considered significant.

cGraduates who reported that they were Hispanic were assigned to the appropriate Hispanic category, regardless of racial designation. Hispanic/Latino includes all persons who selected Mexican or Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic or Latino/a. Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Indigenous groups, and ≥2 racial backgrounds. Underrepresented minority includes black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and ≥2 races. Of 11 171 graduates, 10 970 selected a race or ethnicity category.

Overall, 3737 of 11 771 (31.7%) survey respondents had accepted an academic position at the time of the survey. Within knowledge areas, rates of academic employment among graduates ranged from 26.7% in health services administration (323 of 1209 health services administration graduates) to 35.5% in biostatistics (602 of 1696 biostatistics graduates). Black doctoral graduates were significantly less likely than white doctoral graduates to indicate having accepted an academic position during each survey period (ie, 2003-2007, 2008-2011, and 2012-2015) among biostatistics, epidemiology, and general public health doctoral graduates (all P < .001). When compared with white doctoral graduates, Hispanic doctoral graduates did not generally differ with respect to having accepted an academic position, with the exception that fewer Hispanic doctoral graduates were in health services administration and general public health during some years. The sample of Hispanic doctoral graduates was small during several years and in several knowledge areas (Table 2).

In regression analyses, being married or in a marriage-like relationship was significantly negatively associated with being in an underrepresented minority group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.50, P < .001) and being an underrepresented minority who had accepted an academic position (aOR = 0.68, P < .001; Table 4). Overall, underrepresented minority doctoral graduates were more likely than graduates from non-underrepresented minority groups to have 1, 2, or ≥3 children. Compared with doctoral graduates from the general public health knowledge area, graduates from all other public health knowledge areas were less likely to be either an underrepresented minority or an underrepresented minority who had accepted an academic position. Whereas doctoral graduates in underrepresented minority groups were significantly more likely to be graduates of an R3 institution than an R1 institution (aOR = 5.81, P < .001), they were less likely to graduate from a private for-profit university than from a public institution (aOR = 0.66, P = .05).

Table 4.

Adjusted oddsa of a US research science doctoral graduate being in an underrepresented racial/ethnic minority group, National Science Foundation Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2003-2015b

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds of Being in a Racial/Ethnic Underrepresented Minority Groupc | |

|---|---|---|

| All Graduates (n = 10 054) | Graduates Who Had Accepted an Academic Position by the Time of Survey (n = 3737) | |

| aOR (95% CI) [P Value]d | aOR (95% CI) [P Value]d | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Female | 0.89 (0.79-1.00) [.04] | 0.82 (0.69-0.98) [.03] |

| Mean age (SD), y | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) [.97] | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) [.03] |

| Married or in a marriage-like relationshipe | ||

| No | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Yes | 0.50 (0.44-0.57) [<.001] | 0.68 (0.52-0.82) [<.001] |

| Number of dependents aged <18 ye | ||

| 0 | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| 1 | 1.23 (1.11-1.51) [<.001] | 1.33 (0.80-1.32) [.84] |

| 2 | 1.43 (1.21-1.69) [<.001] | 1.00 (0.75-1.34) [.99] |

| ≥3 | 2.59 (2.05-3.26) [<.001] | 1.34 (0.88-2.02) [.17] |

| US citizen | ||

| No | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Yes | 0.91 (0.80-1.03) [.13] | 1.24 (0.99-1.54) [.05] |

| Knowledge areas | ||

| General public health | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Biostatistics | 0.24 (0.19-0.30) [<.001] | 0.31 (0.21-0.45) [<.001] |

| Environmental health sciences | 0.50 (0.39-0.64) [<.001] | 0.52 (0.34-0.80) [.003] |

| Epidemiology | 0.58 (0.50-0.65) [<.001] | 0.66 (0.54-0.82) [<.001] |

| Health services administration | 0.53 (0.43-0.65) [<.001] | 0.46 (0.31-0.67) [<.001] |

| Carnegie classification of degree-granting institutionf | ||

| Highest research activity (R1) | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Higher research activity (R2) | 1.16 (0.92-1.45) [.24] | 1.19 (0.83-1.69) [.39] |

| Moderate research activity (R3) | 5.81 (4.03-8.40) [<.001] | 1.63 (0.92-2.91) [.10] |

| Other | 1.03 (0.84-1.30) [.81] | 1.04 (0.73-1.47) [.86] |

| Received full tuition remission while a doctoral studente | ||

| No | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Yes | 1.03 (0.91-1.15) [.72] | 1.23 (1.03-1.49) [.03] |

| Type of university from which degree was granted | ||

| Public | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| Private nonprofit | 0.93 (0.82-1.04) [.20] | 1.04 (0.86-1.25) [.71] |

| Private for profit | 0.66 (0.44-0.99) [.05] | 0.56 (0.27-1.06) [.08] |

| Year | ||

| 2003 | 1.00 [Ref] | 1.00 [Ref] |

| 2004 | 0.92 (0.6-1.29) [.65] | 1.08 (0.62-1.91) [.78] |

| 2005 | 1.01 (0.72-1.40) [.94] | 1.03 (0.59-1.81) [.90] |

| 2006 | 1.06 (0.77-1.47) [.74] | 1.16 (0.67-2.00) [.60] |

| 2007 | 1.19 (0.86-1.64) [.27] | 1.08 (0.62-1.88) [.77] |

| 2008 | 1.15 (0.83-1.60) [.40] | 1.50 (0.89-2.55) [.13] |

| 2009 | 1.00 (0.72-1.39) [.99] | 1.29 (0.75-2.22) [.35] |

| 2010 | 1.48 (1.08-2.02) [.01] | 1.50 (0.90-2.52) [.12] |

| 2011 | 1.45 (1.06-1.98) [.02] | 1.35 (0.79-2.29) [.26] |

| 2012 | 1.46 (1.08-1.97) [.01] | 1.36 (0.81-2.26) [.24] |

| 2013 | 1.48 (1.11-2.00) [.008] | 1.11 (0.66-1.86) [.68] |

| 2014 | 1.58 (1.18-2.11) [.002] | 1.45 (0.88-2.40) [.14] |

| 2015 | 1.42 (1.03-1.96) [.06] | 1.22 (0.70-2.12) [.40] |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; ref, reference group.

aAdjusted for all independent variables in the table.

bData source: National Science Foundation.15

cGraduates who reported that they were Hispanic were assigned to the appropriate Hispanic category, regardless of racial designation. Hispanic/Latino includes all persons who selected Mexican or Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic or Latino/a. Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Indigenous groups, and ≥2 racial backgrounds. Underrepresented minority includes black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and ≥2 races.

d P < .05 was considered significant.

eSome participants did not provide this information. Percentages were calculated based on graduates who provided this information at the time of survey completion.

fThe Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education assigns institutions that confer doctoral degrees into 3 categories based on measures of research activity. Other refers to schools that did not receive 1 of these 3 designations because they had been identified as a tribal college or special focus institution.16

In addition, doctoral graduates in underrepresented minority groups who had accepted an academic position were significantly more likely than doctoral graduates from non-underrepresented minority groups to have received full tuition remission while doctoral students (aOR = 1.23, P = .03). Beginning in 2010 (aOR = 1.48, P = .01) and through 2015 (aOR = 1.42, P = .04), the number of doctoral graduates in underrepresented minority groups who received doctoral degrees increased significantly from the baseline year of 2003. However, the number of doctoral graduates in underrepresented minority groups who had accepted an academic position did not differ significantly during the study period. Interactions between each knowledge area and year were not significant in either model.

Discussion

One of the main findings in our analyses was that the number of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates in public health increased from 2003 to 2015. In 2015, for the first time, the proportion of all doctoral graduates who were from an underrepresented minority group approached the proportion of the US population who were from underrepresented minority groups.10 However, because it occurred only in 2015, additional effort will be required to get to the point where the total number of doctoral graduates in underrepresented minority groups reflects US population proportions. We also found significant differences in underrepresented minority doctoral graduates by public health knowledge area. Compared with other knowledge areas, graduates trained in general public health, which includes social and behavioral sciences, were most likely to be from an underrepresented minority group, whereas graduates trained in biostatistics and epidemiology were least likely to be from an underrepresented minority group. This finding may be because underrepresented minority doctoral graduates are more likely to focus on health disparities and other issues that affect vulnerable populations7; these topics may be more commonly aligned with general public health and/or social and behavioral sciences. Our findings pertaining to biostatistics and epidemiology echo previous research that found persons from underrepresented minority groups are less likely than persons from non-underrepresented minority groups to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.18,19

Although the overall number and proportion of doctoral graduates from underrepresented minority groups increased during the study period, this increase was mostly driven by increases in the number of black doctoral graduates. The percentage of Hispanic doctoral graduates was low, ranging from 4% to 7% during the study period. Doctoral graduates in public health from “other” underrepresented minority groups were also rare. Notably, in our study, Hispanic students were underrepresented among doctoral graduates in biostatistics and health services administration. Our data showed that whereas few Hispanic persons obtained doctoral degrees in public health, overall, 32% of Hispanic doctoral graduates had an academic job at or around the time of graduation, a rate that was similar to the rates among persons from non-underrepresented minority groups (white and Asian). Thus, the experiences of Hispanic doctoral graduates may not be the same as the experiences of doctoral graduates in other underrepresented minority groups, particularly black graduates. Methods to attract more Hispanic and black persons into academia may require separate studies to understand how program application, acceptance, matriculation, and graduation rates vary for each underrepresented minority group. Moreover, the Hispanic category includes persons from various cultures, which may mask important differences among graduates with differing Hispanic heritages. Given that the number of Hispanic and other underrepresented minority graduates in health sciences disciplines is growing,20 more research is needed to understand the relative lack of similar growth in the proportion of this minority group obtaining doctoral degrees in public health.

We also found that despite increases in the number of black doctoral graduates over time, we did not observe commensurate increases in the proportion of black graduates who had accepted an academic position at the time of graduation. This pipeline has long been analogized as one in which students flow through graduation and into academic positions.21 Our findings suggest a “leaky pipeline,” similar to other disciplines,22,23 whereby gains in graduation rates among black persons do not translate into similar flows into academic positions. In other words, the pipeline for underrepresented minority doctoral graduates to faculty members is leaking. As such, improvements in the pipeline of persons from underrepresented minority groups to academic positions is a challenge in public health. The lack of a racially and ethnically diverse faculty could potentially exacerbate the leaky pipeline, because faculty members from racial/ethnic minority groups are known to mentor students from racial/ethnic minority groups, and this mentoring can influence students’ selection of academic careers.9

Our study found a positive association between doctoral graduates from underrepresented minority groups who received full tuition remission as doctoral students and accepted an academic position. This finding may be a function of several factors, including that doctoral students who receive tuition remission may be mentored as part of their assigned research or teaching assistantship. We recognize that receiving full tuition support may also select for certain traits and/or interests that may increase one’s proclivity to pursue—or be recruited to—an academic position. Anecdotally, we believe that the mentorship received by doctoral students with research or teaching assistantships helps to prepare them for success on the academic job market regardless of race. Others research has noted that good mentorship allows doctoral students to better express their true self, including their racial identity.24 This information may be an important area for future research, with an emphasis on whether mentorship plays a role in the leaky pipeline phenomenon.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, the SED is administered at or around the time of graduation, when not all doctoral recipients may have found employment. Nevertheless, our data provide a glimpse into the differences in job placements at this period in a doctoral student’s career, which may predict continued success in academia. Moreover, we recognize that the survey forces respondents to select categories that may not accurately describe their true racial/ethnic identity. Although the questionnaire has racial/ethnic categories that would have allowed for a more in-depth analysis of racial differences (eg, American Indian/Alaska Native, Cuban, Mexican or Chicano, or Puerto Rican), small sample sizes prevented us from testing for such differences. We acknowledge the important differences in these smaller groups and call for additional qualitative research to explore how these differences may contribute to experiences in doctoral education that may lead to academic positions. Lastly, although our data represented a near census of all public health doctoral recipients during the study period, our data did not include persons who applied to doctoral programs, matriculated, but then failed to graduate from the programs. Analyzing data on these persons could shed light on many of the trends we identified in our study.

Conclusions

Given the importance of a diverse public health faculty workforce, our research can help schools and programs of public health and other stakeholders to increase the number of persons from underrepresented minority groups in the public health field. Schools and programs of public health may consider programs aimed at increasing the number of underrepresented minority doctoral graduates, especially graduates who choose an academic career. In the management discipline, The PhD Project, founded in 1994, has successfully helped educate minority doctoral students about business doctoral degrees and supported their entry into academic careers. The PhD Project has been credited with an annual rise in the number of earned PhD degrees by minority students from 294 in 1994 to more than 1300 in 2018.25 The public health field could consider a similar program to increase the number of underrepresented minority faculty members in academic public health fields.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. Health policy and management. http://www.aspph.org/study/health-policy-management. Updated 2016. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- 2. Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):624–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, Teperow C, Howard C, Reede J. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antonio AL, Chang MJ, Hakuta K, Kenny DA, Levin S, Milem JF. Effects of racial diversity on complex thinking in college students. Psychol Sci. 2004;15(8):507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gurin P, Dey EL, Hurtado S, Gurin G. Diversity and higher education: theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harv Educ Rev. 2002;72(3):330–367. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Association of Schools of Public Health. Confronting the public health workforce crisis: executive summary. http://www.healthpolicyfellows.org/pdfs/ConfrontingthePublicHealthWorkforceCrisisbyASPH.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed September 25, 2018.

- 8. Coronado F, Koo D, Gebbie K. The public health workforce: moving forward in the 21st century. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5 suppl 3):S275–S277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miner K, Allan S. Future of public workforce training: thought leaders’ perspectives. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(1 suppl):10S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. 2010 Census shows America’s diversity [news release]. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn125.html. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 11. Snyder TD, de Brey C, Dillow SA. Digest of Education Statistics 2014. 50th ed NCES 2016-006 Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freudenberg N, Klitzman S, Diamond C, El-Mohandes A. Keeping the “public” in schools of public health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):S119–S124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Annang L, Richter DL, Fletcher FE, Weis MA, Fernandes PR, Clary LA. Diversifying the academic public health workforce: strategies to extend the discourse about limited racial and ethnic diversity in the public health academy. ABNF J. 2010;21(2):39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Sullivan Commission. Missing persons: minorities in the health professions. A report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce; 2004. https://depts.washington.edu/ccph/pdf_files/SullivanReport.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Survey of earned doctorates. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvydoctorates. Updated December 6, 2016. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 16. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Published 2015. Accessed October 8, 2018.

- 17. IBM Corp. SPSS Version 24.0 [computer program]. Chicago, IL: IBM Corp; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allen-Ramdial SAA, Campbell AG. Reimagining the pipeline: advancing STEM diversity, persistence, and success. Bioscience. 2014;64(7):612–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hurtado S, Newman CB, Tran MC, Chang MJ. Improving the rate of success for underrepresented racial minorities in STEM fields: insights from a national project. New Dir Inst Res. 2010;148:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Hispanics and Latinos in industries and occupations. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2015/hispanics-and-latinos-in-industries-and-occupations.htm. Published 2015. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 21. McGee R, Jr, Saran S, Krulwich TA. Diversity in the biomedical research workforce: developing talent. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79(3):397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanat SF. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hood AC, Foksinska A, Ajigbeda Z, Allman CM, Munchus G, Hannon L. Preparing for a PhD: a transactive memory approach. J High Educ Theory Pract. 2017;17(1):39. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Felder PP, Stevenson HC, Gasman M. Understanding race in doctoral student socialization. Int J Doctoral Stud. 2014;9:21–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25. The PhD Project. Milestones and achievements. https://www.phdproject.org/our-success/milestones-achievements.Updated 2018. Accessed September 25, 2018.