Abstract

Objectives:

Racial/ethnic minority communities in the United States are overrepresented among new HIV diagnoses, yet their inclusion in preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials is inadequate. An analysis of enrollment demographic characteristics from US preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials from 1988 through 2002 showed that enrollment of racial/ethnic minority groups increased. We analyzed enrollment in preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials from 2002 through 2016 and compared our data with data from the previous study, described demographic characteristics of trial participants, and assessed how well this distribution reflected the racial/ethnic distribution of new HIV diagnoses in the United States.

Methods:

We examined data on demographic characteristics from 43 Phase 1 and Phase 2A preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials conducted in the United States and compared the results with those of the previous study. We also compared racial/ethnic distributions from 2011 through 2015 with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data on the number of new HIV diagnoses during the same period.

Results:

Of 3469 participants, 1134 (32.7%) identified as a racial/ethnic minority, a 94% increase from the previous period (634/3731; 17.0%). Percentage annual enrollment of all racial/ethnic minority participants fluctuated from 17% to 53% from mid-2002 to 2016. Percentages of new HIV diagnoses among the general population were 1.9 to 2.9 times the percentage enrollment of black participants and 1.3 to 6.6 times the percentage enrollment of Hispanic/Latino participants in clinical trials for the same period.

Conclusions:

Although enrollment of racial/ethnic minority groups into HIV vaccine clinical trials has increased, it is not proportional to the number of new HIV diagnoses among these groups. To enhance recruitment of racial/ethnic minority groups, the HIV Vaccine Trials Network has prioritized community partnerships and invested resources into staff training.

Keywords: HIV, vaccine, clinical trials, minority, research participation

In the United States, racial/ethnic minority communities are disproportionately affected by HIV and AIDS. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), despite representing only 12% of the overall population, non-Hispanic African Americans accounted for 44% (17 528 of 39 782) of new HIV diagnoses in 2016. At the end of 2015, 42% (405 857 of 972 879) of persons living with HIV in the United States were non-Hispanic African American. In 2016, Hispanic/Latino persons composed 18% of the US population yet accounted for 10 293 (26%) of reported new HIV diagnoses.1 Similar inequalities persist for non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic/Latino persons along the HIV care continuum, from diagnosis to viral suppression.2,3

Geographically, the distribution of HIV infections across the United States varies widely. In 2015, although 37% of the US population resided in the South,4 45% (434 853) of all persons known to be living with HIV lived in the South.1

An essential upstream component to tackling disparities in HIV prevention and treatment is the equitable inclusion of racial/ethnic minority groups in preventive HIV vaccine Phase 1 and Phase 2A clinical trials, which assess the safety of the candidate vaccine and immune response and, in later trial phases, which examine vaccine efficacy. The importance of ensuring equitable representation of both women and racial/ethnic minority groups in clinical trial research has been recognized formally since 1994 by the National Institutes of Health.5 To date, few preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials conducted in the United States have attained adequate sample sizes of participants from racial/ethnic minority groups to perform subgroup analyses.6,7 Without the participation of persons from populations that have the greatest burden of HIV infection, trial outcomes cannot be generalizable to the diversity of the US population and, as such, may have limited relevance for groups that are most affected. In addition, it is essential in these trials to detect any physiological responses or adverse effects to the vaccine that are unique to specific groups, especially for vaccines that advance into future efficacy trials.8 In exploratory subgroup analyses of a Phase 3 trial of a preventive HIV-1 glycoprotein 120 vaccine in 2003, Gilbert et al9 found for 3 of the 4 neutralizing antibody assays performed that nonwhite participants had significantly higher titers—on average one-quarter log10 higher—than white participants. A 2004 analysis of 7 vaccine regimens that enrolled 505 participants found that for 1 glycoprotein 120 regimen, African American participants had significantly higher geometric mean neutralizing antibody titers—2.6 and 4.7 times higher against the 2 strains of HIV tested—than white participants.10

Another important argument for increased inclusion of racial/ethnic minority groups into early stage preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials is that efforts to achieve adequate representation can challenge systemic barriers in access to other prevention interventions, as well as treatment and care for HIV-seropositive persons. Through these trials, participants can gain knowledge about HIV prevention, receive regular risk-reduction counseling and HIV testing, and obtain other health resources that can be disseminated into their communities.

The HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) is a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–funded collaboration working toward the development of a preventive HIV vaccine. A 2005 study by Djomand et al11 analyzed enrollment data from 55 Phase 1 and Phase 2A preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials conducted by the HVTN and its predecessor network, the AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group, in the United States from 1988 through May 2002 (n = 3731) to characterize the distribution of participants by race and ethnicity. The study found an overall increase in the proportion of enrolled participants from racial/ethnic minority groups from 0% (0 of 76) in 1988 to 30% (52 of 172) in 2002. In our study, we evaluated enrollment data from 2002 through 2016 and compared our data with data from the previous study, described the distribution of demographic characteristics among HIV vaccine clinical trial participants, and assessed how well this distribution reflected the racial/ethnic distribution of new HIV diagnoses in the United States.

Methods

We extracted data on demographic characteristics from HVTN case report forms of all participants enrolled in HVTN Phase 1 and Phase 2A preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials in the United States from May 16, 2002, through June 30, 2016. Because Djomand et al limited their analysis to Phase 1 and Phase 2A vaccine clinical trials because of differences in inclusion criteria, we excluded Phase 2B vaccine efficacy clinical trials conducted during this period.12 Eighty participants were enrolled in multiple HIV vaccine clinical trials during this period; we counted them 1 time, at their first enrollment. We included a total of 43 HIV vaccine clinical trials conducted at 18 clinical research sites (CRSs) in 14 cities. We divided CRSs into 4 regions as defined by the US Census Bureau to allow for comparison with regional data on the annual number of new HIV diagnoses reported by CDC.12 We indicated enrollment years for CRSs that were active for only a portion of the review period. The regions were Northeast (Boston, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island [2003-2006]; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [2008-2016]; and Rochester, New York); Midwest (Cleveland, Ohio [2014-2016]; St Louis, Missouri [2002-2006]; and Chicago, Illinois [2012-2013]); South (Birmingham, Alabama; Atlanta, Georgia [2009-2016]; Baltimore, Maryland [2002-2006]; and Nashville, Tennessee); and West (Seattle, Washington; and San Francisco, California).

Participants in the HVTN trials were aged 18-60 and were HIV seronegative at enrollment. For each protocol, site clinical staff members determined whether participants were at low risk for acquiring HIV during screening, and participants were required to commit to maintaining this low-risk profile during the study period and to receiving HIV test results and risk-reduction counseling. Participants needed to be in overall good health as determined by a physical examination, laboratory tests, and a review of their medical histories. Women could not be pregnant, could not be breastfeeding, and had to agree to use effective contraception.

For this analysis, we described the demographic distribution of racial/ethnic minority enrollment by using self-reported race and ethnicity. Site staff members asked participants if they identified with racial categories of American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, black or African American, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, or white. We provided an additional category, “other, specify,” for participants who did not fit into the aforementioned categories. We also asked participants to identify as Hispanic/Latino or non-Hispanic/Latino. To allow for comparison with the study by Djomand et al and CDC data, we combined race and ethnicity; we counted participants who self-identified as Hispanic/Latino by this identity rather than by any race with which they identified and considered non-Hispanic participants who specified more than 1 race to be multiracial. In addition, for comparison with the study by Djomand et al, we combined the categories of Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander into 1 category, and we combined multiracial and “other, specify” into 1 category.

We examined data on percentages of racial/ethnic minority enrollment by year of enrollment and CRS region. We compared racial/ethnic minority enrollment into Phase 1 vaccine clinical trials over time with the analysis by Djomand et al. Djomand et al limited their time-trend analysis to Phase 1 vaccine clinical trial participants because there were large time gaps between enrollment periods for the 3 Phase 2A trials conducted during their analysis period. We also compared data on the proportion of racial/ethnic minority enrollment into Phase 1 and Phase 2A vaccine clinical trials with the proportion of persons who self-identified as a racial/ethnic minority among new HIV diagnoses; we obtained these data from the National HIV Surveillance System (NHSS).13–16 Because of changes over time in what data were available in these NHSS reports, calculations of total new HIV diagnoses from 2002 through 2007 included persons aged ≥13, whereas data from 2008 through 2016 were limited to adults aged 20-60.

We also used NHSS reports to compare racial/ethnic minority enrollment with newly diagnosed HIV infections at the regional level. We used reports from 2011-2015 to compare HVTN enrollment from these same years and included persons aged ≥13. We grouped CRSs by US Census–defined regions for analysis. Because of a small number of participants in other racial/ethnic categories, we included only those participants who self-identified as non-Hispanic black or Hispanic/Latino in the regional comparisons.

We performed all analyses by using Stata version 14.17 We used the Pearson χ2 test to compare proportions of racial/ethnic minority enrollment in the study by Djomand et al with proportions in our study. The study was approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board.

Results

Overall Trends and Comparison With Findings From Djomand et al

Of 3469 participants included in this analysis, 3038 (87.6%) were enrolled in 41 Phase 1 trials and 431 (12.4%) were enrolled in 2 Phase 2A trials. When stratified by region, 1416 (40.8%) participants were enrolled in the Northeast, 194 (5.6%) in the Midwest, 1176 (33.9%) in the South, and 683 (19.7%) in the West. Across all years and CRSs, 2332 (67.2%) enrolled participants identified as non-Hispanic white, 600 (17.3%) as non-Hispanic black or African American, 267 (7.7%) as Hispanic/Latino, 112 (3.2%) as Asian or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 9 (0.3%) as American Indian/Alaska Native, and 150 (4.3%) as multiracial or other (Table).

Table.

Demographic characteristics at enrollment of participants in HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Phase 1 and Phase 2a trials, by trial phase and enrollment region, 2002-2016

| No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Region | ||||||

| Characteristic | Total | 1 | 2A | Northeast | Midwest | South | West |

| Age, y | |||||||

| <20 | 230 (6.6) | 188 (6.2) | 42 (9.7) | 124 (8.8) | 18 (9.3) | 57 (4.8) | 31 (4.5) |

| 20-29 | 1789 (51.6) | 1547 (50.9) | 242 (56.1) | 736 (52.0) | 99 (51.0) | 614 (52.2) | 340 (49.8) |

| 30-39 | 786 (22.7) | 694 (22.8) | 92 (21.3) | 268 (18.9) | 51 (26.3) | 284 (24.1) | 183 (26.8) |

| 40-49 | 601 (17.3) | 553 (18.2) | 48 (11.1) | 263 (18.6) | 25 (12.9) | 202 (17.2) | 111 (16.3) |

| ≥50 | 63 (1.8) | 56 (1.8) | 7 (1.6) | 25 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 19 (1.6) | 18 (2.6) |

| Sex at birth | |||||||

| Female | 1565 (45.1) | 1364 (44.9) | 201 (46.6) | 633 (44.7) | 70 (36.1) | 569 (48.4) | 293 (42.9) |

| Male | 1904 (54.9) | 1674 (55.1) | 230 (53.4) | 783 (55.3) | 124 (63.9) | 607 (51.6) | 390 (57.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 102 (2.9) | 93 (3.1) | 9 (2.1) | 56 (4.0) | 3 (1.6) | 18 (1.5) | 25 (3.7) |

| Non-Hispanic black/African American | 600 (17.3) | 511 (16.8) | 89 (20.6) | 217 (15.3) | 31 (16.0) | 321 (27.3) | 31 (4.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 267 (7.7) | 236 (7.8) | 31 (7.2) | 154 (10.9) | 8 (4.1) | 37 (3.1) | 68 (10.0) |

| Non-Hispanic multiracial | 124 (3.6) | 116 (3.8) | 8 (1.9) | 52 (3.7) | 0 | 20 (1.7) | 52 (7.6) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 9 (0.3) | 8 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 3 (1.6) | 2 (0.2) | 0 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 10 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 7 (1.0) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 2332 (67.2) | 2042 (67.2) | 290 (67.3) | 917 (64.8) | 147 (75.8) | 772 (65.6) | 496 (72.6) |

| Other | 22 (0.6) | 19 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | 15 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| No response | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.4) |

| Total | 3469 | 3038 | 431 | 1416 | 194 | 1176 | 683 |

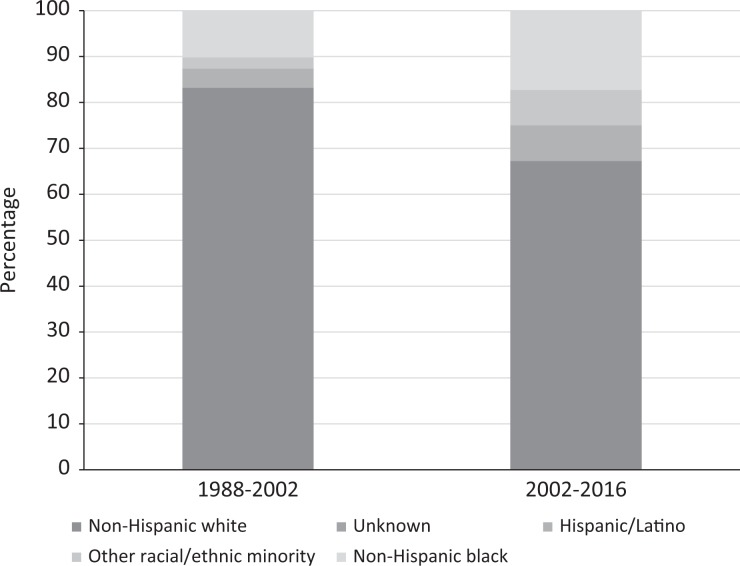

In a comparison of the distribution of Phase 1 and Phase 2A HIV vaccine clinical trial participants by race/ethnicity enrolled during 2002-2016 with participants enrolled during 1988-2002, the proportion of non-Hispanic white participants decreased from 83.2% to 67.2%, and the proportion of racial/ethnic minority participants increased from 16.7% to 32.8% (P < .001) (Figures 1a and b).

Figure 1.

A comparison of the racial/ethnic distribution of participants in the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Phase 1 and Phase 2A trials during 1988-2002 (N = 3731) and 2002-2016 (N = 3469). Data source for 1988-2002: Djomand et al.11 Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, multiracial, and “other” categories were combined into “other racial/ethnic minority” because of small numbers.

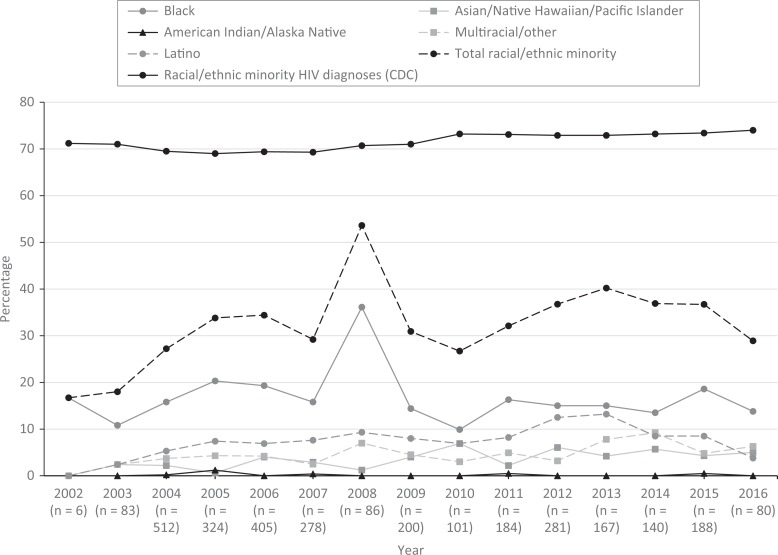

When we disaggregated the distribution of Phase 1 HIV vaccine clinical trial participants enrolled from 2002 through 2016 by race/ethnicity and enrollment year, the percentage enrollment of all participants who identified as a racial or ethnic minority ranged from 17% to 40% for all years except for 2008 (53%). Unlike Djomand et al, who reported a significant increase in participation among participants from racial/ethnic minority groups in Phase 1 HIV vaccine clinical trials over time, we found no upward or downward trends (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Racial/ethnic minority enrollment in the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Phase 1 trials, 2002-2016. The dotted line represents the proportion of racial/ethnic minority persons among new HIV diagnoses according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National HIV Surveillance System.14–17 Non-Hispanic participants who self-identified as >1 race were considered multiracial. Participants who provided their own racial identity outside of the defined categories were considered other.

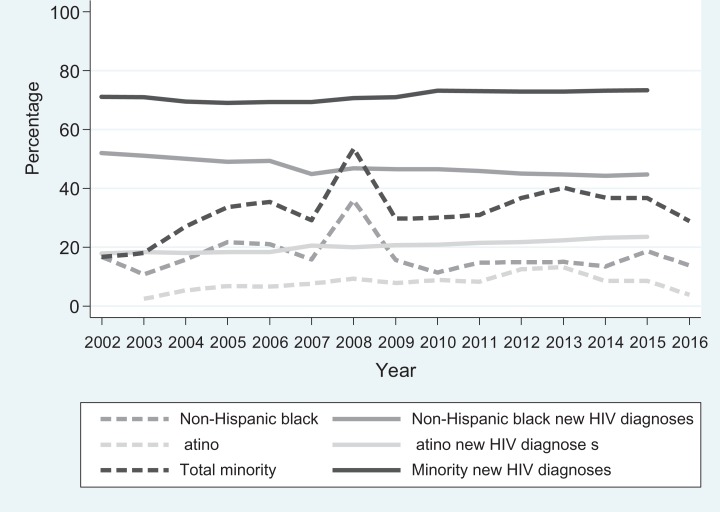

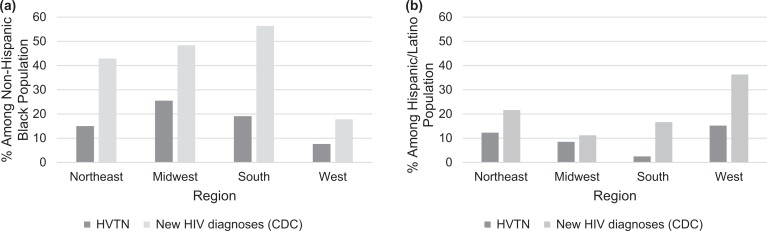

Regional Trends and Comparison With New HIV Diagnoses

From 2002 through 2016, the number of newly diagnosed HIV infections among persons who identified as a racial/ethnic minority ranged from 23 238 to 33 348 in the NHSS, accounting for 69% to 73% of total new HIV diagnoses. Findings were similar for non-Hispanic black and Latino persons examined separately over time (Figure 3) or separately by region during 2011-2015 (Figures 4a and b). By region, the percentage of non-Hispanic black persons among new HIV diagnoses ranged from 1.9 to 2.9 times the percentage enrollment of non-Hispanic black trial participants (Figure 4a). The burden of HIV diagnoses among Hispanic/Latino persons was 1.3 to 6.6 times that of the percentage of Hispanic/Latino HIV vaccine clinical trial enrollees (Figure 4b). The South had the largest gap between HIV vaccine clinical trial enrollment and the number of new HIV diagnoses among non-Hispanic black and Hispanic/Latino persons (Figures 4a and b).

Figure 3.

Racial/ethnic minority enrollment in the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Phase 1 and Phase 2A HIV vaccine clinical trials compared with percentage of corresponding racial/ethnic minority groups among new HIV diagnoses according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National HIV Surveillance System, 2002-2016.14–17

Figure 4.

Percentage of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic/Latino participants in the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Phase 1 and Phase 2a preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials compared with percentage of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic/Latino persons among new HIV diagnoses according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National HIV Surveillance System, 2011-2015, disaggregated by region.14–17 Percentages were calculated from the sum totals of study years 2011-2015.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates that the enrollment of persons from racial/ethnic minority groups in Phase 1 and Phase 2A HVTN preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials during 2002-2016 was greater than enrollment in HIV vaccine clinical trials during 1988-2002. However, disparities persisted between enrollment and the annual number of new HIV diagnoses nationally and regionally.

Unlike preventive HIV vaccine efficacy trials that recruit participants at higher risk of HIV infection, early phase HIV vaccine clinical trials focus on populations that are less vulnerable to HIV infection and, as such, may not match the demographic characteristics of the populations most at risk for acquiring HIV. Nevertheless, inclusion of racial/ethnic minority groups into early phase HIV vaccine clinical trials can serve to identify differences in response to a candidate vaccine and promote access for traditionally underrepresented populations to the benefits of clinical research.

Research on barriers to participation in clinical trials generally, including barriers that are specific to HIV vaccine clinical trials, has documented several factors that can present challenges for recruitment and enrollment of racial/ethnic minority groups: distrust of research and the motives of researchers18–22; disparities in access to routine health care, the underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minority groups in the health and research workforce and subsequent lack of cultural humility in many clinical environments, and language, geographic, and cultural barriers23–27; as well as perceived risks of potential side effects or social harms, including vaccine-induced seropositivity.28–31 Vaccine-induced seropositivity is the phenomenon of testing reactive on HIV testing kits because of antibodies generated by an HIV vaccine rather than because of antibodies generated by HIV infection. Use of tests that detect HIV virus can detect true HIV infection; however, these tests are not commonly the first line of testing used in public health settings, potentially requiring participants to obtain HIV testing through study sites after study completion.

Although these barriers to recruitment are complex, they do not negate the evidence that shows a willingness to participate in research among members of racial/ethnic minority communities.32–34 Furthermore, altruism as a major motivator to participate in research is common among persons from racial/ethnic minority groups.20,35

By prioritizing partnerships with and leveraging expert feedback from racial/ethnic minority communities and community-based organizations throughout the research process, the HVTN has implemented various strategies to facilitate increased racial/ethnic minority awareness of and involvement in preventive HIV vaccine research. These strategies include increasing diversity among staff members and providing cultural responsiveness training to all employees, using persons from racial/ethnic minority groups as models in advertising, and providing support and technical assistance to CRSs and their community-based partners to promote the mutual exchange of ideas and expertise. These efforts likely contributed to the increase in racial/ethnic minority enrollment in the early 2000s and sustained levels in later years.

Although we had originally hoped to do so, we were unable to include participants’ self-reported information on sexual orientation and gender identity in our analysis because of several changes in the collection of demographic information during the study period. These changes resulted in missing data on sexual orientation and gender identity for participants enrolled in trials that did not collect these data. This limitation also exists in HIV surveillance at the state and national levels; to date, HIV surveillance systems have not routinely collected data on sexual orientation or gender identity of HIV-diagnosed persons. Currently, Washington State is considering adding questions on gender and sexual orientation to its collection of data on newly diagnosed HIV infections. In 2007, the HVTN’s demographic case report form was redesigned to adopt the recommendation of CDC to use the 2-step approach: collecting data on sex assigned at birth and self-identified gender.36,37 In addition, in 2015, the HVTN added a standardized question to improve the collection of data on sexual orientation. Across the HVTN, all participants are asked, “How do you identify your sexual orientation?” Responses include: gay/lesbian/homosexual, bisexual, queer, 2-spirit, straight/heterosexual, additional category, specify, not sure, and prefer not to answer. These important revisions in data collection will allow for more robust collection and analyses of data on gender identity and sexual orientation.

Our inability to make any conclusions from the data on sexual orientation and gender identity also prevented us from exploring how the intersectionality of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity informs disproportionate vulnerability to HIV infection and barriers to recruitment in preventive HIV vaccine clinical trials. Intersectionality is essential when discussing health disparities because persons with multiple devalued identities may face an increased risk of acquiring HIV and more barriers to prevention, testing, and care than persons with one devalued identity.38–42 Pursuing research and engaging in activities that maintain the integrity of an intersectional framework provide a more accurate representation of the burden of HIV that, in turn, enables a more effective and informed delivery of resources into communities most affected by HIV.43,44

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the CRSs participating in the HVTN and the number of enrollment slots available to a CRS in a specific year were not constant during the study period, which may have affected the distribution of racial/ethnic minority participation. Also, it is known that some participants do not live in the metropolitan area where their CRS is located. Because the residence of participants outside of designated metropolitan areas presented a challenge in comparing new HIV diagnosis data with enrollment data on a CRS level, we undertook a regional comparison, which limited us from detecting site-specific differences in racial/ethnic minority recruitment patterns. A more in-depth analysis would be required to fully understand which recruitment practices made a measurable difference in the recruitment of racial/ethnic minority group members, including, for example, if the marked increase in racial/ethnic minority enrollment in 2008 could be attributable to specific site activities.

Second, we did not include Phase 2B efficacy trials conducted by the HVTN to compare the new findings with those of the study by Djomand et al, which did not include Phase 2B trial participants. Going forward, examining enrollment data from HVTN Phase 2B trials likely would provide a more accurate calculation of racial/ethnic minority inclusion.

Conclusions

Persons in the United States who identify as members of a racial/ethnic minority group have a complex set of barriers that impede awareness of, access to, and enrollment into HIV vaccine clinical trials. This low enrollment contributes to a dearth of data on differences in immunogenicity, adverse effect occurrence, and reactivity to candidate vaccines among racial/ethnic minority subgroups.

Although enrollment of racial/ethnic minority groups into HIV vaccine clinical trials conducted by the HVTN has increased, it still lags behind the proportional representation of new HIV diagnoses among these groups. To promote racial/ethnic minority group participation, the HVTN has prioritized identifying new and strengthening existing partnerships in racial/ethnic minority communities and has invested resources into training HVTN staff members on cultural responsiveness, implicit bias, and health disparities. Despite extensive efforts by the HVTN to reach out to racial/ethnic minority communities, it is unlikely that enrollment in HVTN preventive early phase HIV vaccine clinical trials will be proportional to regional data on the number of new HIV diagnoses among racial/ethnic minority groups, because early phase trials are designed to enroll populations with low behavioral risk for HIV infection. However, comparison of enrollment with these national data can serve as a yardstick for improving the recruitment of racial/ethnic minority groups overall.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many study participants, study site staff members, and investigators for their time and effort in conducting the studies with data included in this analysis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The clinical trials reported in this analysis were conducted by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)–funded HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) with the support of NIAID US Public Health Service grants UM1 AI068614 (Leadership and Operations Center: HVTN), UM1 AI068618 (Laboratory Center: HVTN), and UM1 AI068635 (Statistical and Data Management Center: HVTN). NIAID played no role in the study design and the decision to publish this material. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAID or the National Institutes of Health. Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, P2C HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2016. HIV Surveill Rep. 2017;28:1–125. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dasgupta S, Oster AM, Li J, Hall HI. Disparities in consistent retention in HIV care—11 states and the District of Columbia, 2011-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(4):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grossman CI, Purcell DW, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Veniegas S. Opportunities for HIV combination prevention to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):237–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population: April 1, 2010, to July 1, 2014. 2018. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?%20pid=PEP_2014_PEPANNRES&src=pt. Accessed October 28, 2018.

- 5. Freedman LS, Simon R, Foulkes MA, et al. Inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials and the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993—the perspective of NIH clinical trialists. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16(5):277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sobieszczyk ME, Xu G, Goodman K, Lucy D, Koblin BA. Engaging members of African American and Latino communities in preventive HIV vaccine trials. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2009;51(2):194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, et al. HIV vaccine trial participation among ethnic minority communities: barriers, motivators, and implications for recruitment. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2006;41(2):210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. George S, Duran N, Norris K. A. systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilbert PB, Peterson ML, Follmann D, et al. Correlation between immunologic responses to a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine and incidence of HIV-1 infection in a phase 3 HIV-1 preventive vaccine trial. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(5):666–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montefiore DC, Metch B, McElrath MJ, et al. Demographic factors that influence the neutralizing antibody response in recipients of recombinant HIV-1 gp120 vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(11):1962–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Djomand G, Katzman J, Di Tomasso D, et al. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities in NIAID-funded networks of HIV vaccine trials in the United States, 1988 to 2002. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(5):543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. US Census Bureau. Geography. 2015. https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/webatlas/regions.html. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, 2002. HIV/AIDS Surveill Rep. 2003;14:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2006. HIV/AIDS Surveill Rep. 2007;18:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents, by sex and transmission category, 2010—46 states and 5 US dependent areas. HIV Surveill Rep. 2011;22:1–79. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveill Rep. 2016;27:1–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17. StataCorp. Stata Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shavers-Hornaday VL, Lynch CR, Burmeister LF, Torner JC. Why are African Americans under-represented in medical research studies? Impediments to participation. Ethn Health. 1997;2(1):31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scharff DP, Matthews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moutsiakis DL, Chin PN. Why blacks do not take part in HIV vaccine trials. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(3):254–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sengupta S, Strauss RP, DeVellis R, Quinn SC, DeVellis B, Ware WB. Factors affecting African-American participation in AIDS research. J Acquir Immun Def Syndr. 2000;24(3):275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heller C, Balls-Berry JE, Nery JD, et al. Strategies addressing barriers to clinical trial enrollment of underrepresented populations: a systematic review. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39(2):169–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sullivan PS, McNaghten AD, Begley E, Hutchinson A, Cargill VA. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(3):242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):852–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ford ME, Siminoff LA, Pickelsimer E, et al. Unequal burden of disease, unequal participation in clinical trials: solutions from African American and Latino community members. Health Soc Work. 2013;38(1):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castillo-Mancilla JR, Cohn SE, Krishnan S, et al. Minorities remain under-represented in HIV/AIDS research despite access to clinical trials. HIV Clin Trials. 2014;15(1):14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heumann C, Cohn SE, Krishnan S, et al. Regional variation in HIV clinical trials participation in the United States. South Med J. 2015;108(2):107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coombs A, McFarland W, Ick T, Fuqua V, Buchbinder SP, Fuchs D. Long-chain peer referral to recruit black MSM and black transgender women for an HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Def Syndr. 2014;66(4):94–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buchbinder SP, Metch B, Holte SE, Scheer S, Coletti A, Vittinghoff E. Determinants of enrollment in a preventive HIV vaccine trial: hypothetical versus actual willingness and barriers to participation. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2004;36(1):604–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newman PA, Daley A, Halpenny R, Loutfy M. Community heroes or “high risk” pariahs? Reasons for declining to enroll in an HIV vaccine trial. Vaccine. 2008;26(8):1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Salihu HM, Wilson RE, King LM, Marty PJ, Whiteman VE. Socio-ecological model as a framework for overcoming barriers and challenges in randomized control trials in minority and underserved communities. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;3(1):85–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koblin BA, Heagerty T, Sheon A, et al. Readiness of high-risk populations in the HIV Network for Prevention Trials to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials in the United States. AIDS. 1998;12(7):785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dhalla S, Poole G. Effect of race/ethnicity on participation in HIV vaccine clinical trials and comparison to other trials of biomedical prevention. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2014;10(7):1974–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gwadz MV, Leonard NR, Nakagawa A, et al. Gender differences in attitudes towards AIDS clinical trials among urban HIV-infected individuals from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kerkorian D, Traube DE, McKay MM. Understanding the African American Research Experience (KAARE): implications for HIV prevention. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5(3):295–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among transgender people. Updated 2018. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/transgender. Accessed August 5, 2018.

- 37. University of California, San Francisco, Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. Recommendations for inclusive data collection of trans people in HIV prevention, care & services. http://www.transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?%20page=lib-data-collection. Accessed March, 26. 2018.

- 38. Sangaramoorthy T, Jamison A, Dyer T. Intersectional stigma among midlife and older black women living with HIV. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(12):1329–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Freeman R, Gwadz MV, Silverman E, et al. Critical race theory as a tool for understanding poor engagement along the HIV care continuum among African American/black and Hispanic persons living with HIV in the United States: a qualitative exploration. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bogart LM, Dale SD, Christian J, et al. Coping with discrimination among HIV-positive black men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(7):723–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Poteat T, German D, Flynn C. The conflation of gender and sex: gaps and opportunities in HIV data among transgender women and MSM. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(7-8):835–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilson PA, Valera P, Martos AJ, Wittlin NM, Munoz-Laboy MA, Parker RG. Contributions of qualitative research in informing HIV/AIDS interventions targeting black MSM in the United States. J Sex Res. 2016;53(6):642–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hankivsky O, Doyal L, Einstein G, et al. The odd couple: using biomedical and intersectional approaches to address health inequities. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(suppl 2):1326686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hankivsky O, Grace D, Hunting G, et al. An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]