Abstract

Pulmonary veins (PVs) are a major source of ectopic beats that initiate AF. PV isolation from the left atrium is an effective therapy for the majority of paroxysmal AF. However, investigators have reported that ectopy originating from non-PV areas can also initiate AF. Patients with recurrent AF after persistent PV isolation highlight the need to identify non-PV ectopy. Furthermore, adding non-PV ablation after multiple AF ablation procedures leads to lower AF recurrence and a higher AF cure rate. These findings suggest that non-PV ectopy is important in both the initiation and recurrence of AF. This article summarises current knowledge about the electrophysiological characteristics of non-PV AF, suitable mapping and ablation strategies, and the safety and efficacy of catheter ablation of AF initiated by ectopic foci originating from non-PV areas.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, non-pulmonary vein, trigger, catheter ablation

Catheter ablation of AF has become an established therapy and may have the potential to cure this most commonly encountered sustained arrhythmia. Previous studies have demonstrated that pulmonary veins (PVs) are a major source of the ectopic beats that initiate AF. PV isolation in patients with symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs is effective; however, it is difficult to eliminate all instances of AF.[1–3] If ectopic foci consistently come from a non-PV area and a pattern of spontaneous onset of AF is onset confirmed, the earliest ectopic site is defined as the non-PV trigger initiating AF.[2,4–7] Ectopy originating from non-PV areas can initiate AF and can cause it to recur after PV isolation.[4–31] Non-PV ablation after multiple AF ablation procedures decreases the risk of recurrence and increases the cure rate.[10,19–21,23,25,28,29] Although several ablation strategies have been developed, the outcomes of ablation are not improved unless substrate modification targets AF triggers.[30] Taking all of these considerations into account, non-PV ectopy plays important role in both AF initiation and recurrence.[2,4–7,20,29,30,32–34]

Mapping studies of non-PV foci have revealed that triggers are often found in anatomically predictable regions, such as the left atrial wall, thoracic veins and crista terminalis, and can be sustained or non-sustained triggers of AF. These areas can be mapped by specific multielectrode catheters positioned in key regions and ablated after the AF is induced and localised, or they can be ablated empirically without the induction of ectopy.[1–34] This review focuses on catheter ablation of AF initiated by non-PV triggers, summarising the electrophysiological characteristics, mapping and ablation strategies, their safety and efficacy.

Electrophysiological Features of AF Originating from Non-pulmonary Vein Areas

Incidence of Initiators

Several important concepts have been proposed regarding the role of non-PV ectopy in initiating AF.[2,4–7] AF is initiated by non-PV disturbance of the cardiac rhythm in up to 39 % of cases.[3,8–10,32–38] The left atrium (LA) (25.3 %), superior vena cava (SVC) (22.2 %), coronary sinus (CS) (18.0 %), right atrium (RA) including the crista terminalis (17.4 %), interatrial septum (7.9 %), and ligament of Marshall (LOM) (3.9 %) are the areas in which non-PV triggers of de novo AF are most commonly found (Table 1), whereas the SVC, interatrial septum and LA are the most common non-PV trigger sites in recurrent AF (Table 2).[6–30] Furthermore, there is a higher incidence of non-PV triggers initiating AF in females and in patients with an enlarged LA.[39]

Table 1: De Novo AF Originating from Non-pulmonary Vein Areas.

| Publication | Number of patients | Mean age (years) | Gender | Number of Ectopic Foci | Mapping Modality | Origin of Ectopy (No of Foci) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-PV ectopy | Total | Non-PV ectopy | RA | SVC | CS | IAS | LA | LOM | SVT | Others | ||||

| Lin et al. 2003[6] | 240 | 68 (28 %) | 61±13 | 43 M/25 F | 358 | 73 (20 %) | C, basket, ICE | CT 10 | 27 | 1 | 1 | PW (28) | 6 | ||

| Shah et al. 2003[8] | 160 | 36 (23 %) | NA | NA | NA | 86 | C | 5 | 3* | 4 | PW (30), PV os (39), others (5) | 16** | |||

| Beldner et al. 2004[9] | 401 | 68 (17 %) | NA | NA | NA | 83 | C, ICE, CARTO | CT 11, TA 4, ER 13 | 4 | 3 | FO (4) | PW (15), MA (7) | 20‡ | 2 | |

| Suzuki et al. 2004[10] | 127 | 18 (14 %) | NA | NA | NA | 20 | C | CT 4 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Yamada et al. 2007[11] | 147 | 31 (21 %) | NA | NA | NA | 38 | Basket | CT 5 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 5§ | ||

| Valles et al. 2008[12] | 45 | NA | NA | NA | 57 | 6 (11 %) | C | CT 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Lo et al. 2009[13] | 85† | 17 (20%) | NA | NA | NA | 17 | NavX | 6 | 2 | 2 | PW (3) | 4 | |||

| Yamaguchi et al. 2010[14] | 65 | 17 (26 %) | 62±8 | 13 M/4 F | 95 | 19 (20 %) | Array | CT 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 | ||

| Chang et al. 2013[15] | 660† | 132 (20 %) | 51±12 | 86 M/46 F | 779 | 146 (19 %) | NavX | CT 15 | 53 | 22 | 13 | 23 | 20 | ||

| Zhang et al. 2014[16] | 300 | 29 (10 %) | NA | NA | NA | 29 | C | CT 1 | 27 | PV os (1) | |||||

| Cheng et al. 2014[17] | 76 | 13 (17 %) | NA | NA | NA | 13 | C | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2** | ||||

| Kuroi et al. 2015[18] | 446 | 26 (6 %) | NA | NA | NA | 28 | CARTO | 9 | 10 | 2 | 7 | ||||

| Hayashi et al. 2015[19] | 304 | 59 (19 %) | NA | NA | 178 | 43 (24 %) | CARTO/NavX | 8 | 19 (PLSVC2)* | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | ||

| Lo et al. 2015[20] | 530 | 70 (13 %) | NA | NA | 612 | 85 (14 %) | NavX | CT 4 | 31 | 13 | 10 | 17 | 10 | ||

| Hayashi et al. 2016[21] | 216 | 43 (20 %) | NA | NA | 147 | 58 (39 %) | C | CT 4, RAF 3 | 17 (PLSVC2)* | 1 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 12** | |

| Hasebe et al. 2016[22] | 39 | 7 (18 %) | 51±13 | 6 M/1 F | 53 | 11 (21 %) | C | CT 5, TA 1, RAF 4 | 1 | ||||||

| Zhao et al. 2016[23] | 720 | 266 (37 %) | NA | NA | NA | 423 | C | 62 | 23 | 195 | 143 | ||||

| Santangeli et al. 2016[24] | 1531 | 165 (11 %) | NA | NA | NA | 195‖ | CARTO/NavX | 70 | 26 | 23 | 27 | 7 | 42‡ | ||

| Hung et al. 2017[25] | 579 | 95 (16 %) | NA | NA | NA | 99 | NavX | 14 | 42 | 2 | 11 | 14 | 16 | ||

| Narui et al. 2017[26] | 255† | 34 (13 %) | NA | NA | NA | 34 | C | 7 | 21 | 6 | |||||

| Allamsettey et al. 2017[27] | 32† | 11 (34 %) | NA | NA | 85 | 15 (18 %) | Velocity | 2 | 10¶ | 3 | |||||

| Takigawa et al. 2017[28] | 865 | 68 (8 %) | NA | NA | NA | 76 | C | CT 16 | 14 | 8 | 27 | 11 | |||

| Total | 7,823 | 1,273 (16.3 %) | 1597 | 278 (17.4 %) | 355 (22.2 %) | 288 (18.0 %) | 126 (7.9 %) | 404 (25.3 %) | 63 (3.9 %) | 62 (3.9 %) | 37 (2.3 %) | ||||

*Includes persistent left superior vena cava. †33 paroxysmal and 52 non-paroxysmal AF patients in Lo et al.,[13] 526 and 134 in Chang et al.,[15] 150 and 105 in Narui et al.,[26] and 26 and 6 in Allamsetty et al.[27] ‡Atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia and atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia triggered AF. §Five foci were speculated to have an epicardial origin. **16, 2 and 12 foci were unmappable non-PV foci, respectively. ‖Numbers of non-PV ectopic foci were estimated based on the percentage of patients with non-PV ectopic foci. ¶Non-PV triggers were observed in 34 % of the total population (26 paroxysmal and 6 nonparoxysmal AF). A total of 45 % of non-PV triggers (16 % of the total population) were observed in the aortic encroachment area. Array = EnSite™ Array™ noncontact mapping system (Abbott); Basket = basket catheter; C = conventional mapping; CARTO = CARTO® system (Biosense Webster); CS = coronary sinus; CT = crista terminalis; ER = Eustachian ridge; F = female; FO = fossa ovalis; IAS = interatrial septum; ICE = intracardiac echocardiography; LA = left atrium; LOM = ligament of Marshall; M = male; MA = mitral annulus; NA = data not available; NavX = EnSite™ NavX™ system (Abbott); PLSVC = persistent left superior vena cava; PV = pulmonary vein; PVos = ostia of an ablated pulmonary vein including the zone between ipsilateral veins; PW = left atrial posterior wall; RA = right atrium; RAF = right atrial free wall; SVC = superior vena cava; SVT = supraventricular tachycardia; TA = tricuspid annulus; Velocity = EnSite™ Velocity™ cardiac mapping system (Abbott). Some data reproduced with permission from Higa et al., 2011.34

Table 2: Recurrent AF Originating from Non-pulmonary Vein Areas.

| Publication | Number of patients | Mean age (years) | Gender | Number of Ectopic Foci | Mapping Modality | Origin of Ectopy (No of Foci) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-PV ectopy | Total | Non-PV ectopy | RA | SVC | CS | IAS | LA | LOM | SVT | Others | ||||

| Takigawa et al. 2005[29] | 207 | 95 (46 %)* | 63±11 | 69 male/26 female | NA | 92 | C | 34 | 16 | 12 | 38† | ||||

| Lo et al. 2015[20] | 94 | 11 (12 %)* | NA | NA | 102 | 12 (12 %) | NavX | 8 | 25 | 8 | 42 | 17 | |||

| Lo et al. 2015[20] | 52 | 15 (29 %)‡ | NA | NA | 75 | 24 (32 %) | NavX | 17 | 25 | 4 | 42 | 13 | |||

| Mahonty et al. 2017[30] | 84 | 74 (88 %)§ | NA | NA | NA | NA | CARTO | 9‖ | 64 | 22 | 69 | ||||

*Incidence of non-PV foci during a second session of catheter ablation of paroxysmal AF. †In this study,35 foci (38 %) were unmappable non-PV foci. ‡Incidence of non-PV foci during the third to fifth catheter ablation of paroxysmal AF. §Incidence of non-PV foci during a second session of catheter ablation of paroxysmal AF with severe left atrial scarring. The non-PV triggers were mostly (90.5 %) located in areas outside the scar region. ‖9 % of non-PV foci were located on the crista terminalis/superior vena cava. C = conventional mapping; CARTO = CARTO® system (Biosense Webster); CS = coronary sinus; IAS = interatrial septum; LA = left atrium; LOM = ligament of Marshall; NA = data not available; NavX = EnSite™ NavX™ system (Abbott); RA = right atrium; SVC = superior vena cava; SVT = supraventricular tachycardia. Some data reproduced with permission from Higa et al., 2011.34

Pathophysiology

Histological analysis of the embryonic sinus venosus has identified areas capable of spontaneous depolarisation at the junctions between different embryonic tissues, such as the RA–SVC junction, crista terminalis and CS ostium.[40–42] The SVC is a major origin of non-PV triggers of AF.[5,8,32–34,43–47] Heterogeneity of the SVC sleeve and arrhythmogenicity of cardiomyocytes isolated from the SVC have been reported.[41,42] An excitation from the SVC can conduct to the RA through the myocardial extensions of the SVC sleeve.[48–50] Diseased human atria are hypopolarised in comparison to normal atria, which may account for the abnormal automaticity and/or activity originating from the LA wall.[51–53] The crista terminalis, which is an area exhibiting abnormal automaticity, anisotropy and slow conduction, may serve as an arrhythmogenic substrate for AF initiation and perpetuation.[54,55] Catecholamine-sensitive ectopy arising from the crista terminalis exhibits high-frequency depolarisations with fibrillatory conduction.[6] The LOM is an embryological remnant of the left SVC and contains arrhythmogenic myocardial fibres with sympathetic innervation. Several reports have demonstrated the existence of catecholamine-sensitive tissue within the LOM that has abnormal automaticity, and which could be a potential source of AF initiation.[6,56–58]

The musculature within the CS also has arrhythmogenic activity, with spontaneous depolarisations induced by catecholamine loading.[59,60] Abnormal dilatation due to an unroofed CS can be an arrhythmogenic focus of AF initiation.[61] A recent study found that 45 % of non-PV triggers of AF were in the area of aortic encroachment, which equates to 16 % of the total population with AF. There is also an arrhythmogenic substrate exhibiting low voltage and fractionated electrograms with a prolonged duration in the anterior part of the LA at the site of aortic encroachment.[27]

Diagnosis

Provoking Ectopy

To successfully provoke ectopy with AF initiation, antiarrhythmic drugs should be discontinued for a period of at least five half-lives before the patient undergoes electrophysiological study. Spontaneous initiation of ectopic beats preceding AF should be observed at baseline or after isoproterenol loading.[32–34] In the case of deep sedation or general anaesthesia, it is necessary to give the patient a high dose of isoproterenol to induce ectopy with AF initiation. Adenosine or adenosine triphosphate can also be used, especially in young patients with vagal AF and with a family history of AF.[18]

If ectopy does not occur, short-burst atrial pacing can be delivered with intermittent pauses or, failing that, atrial burst pacing to induce sustained AF. Careful monitoring for spontaneous reinitiation of AF is required after internal or external cardioversion. The induction of spontaneous AF initiation should be attempted at least twice to confirm the location of ectopy, the initiation pattern of spontaneous AF, and the earliest activation site (the AF initiator).[2,4–7,32–34]

Mapping

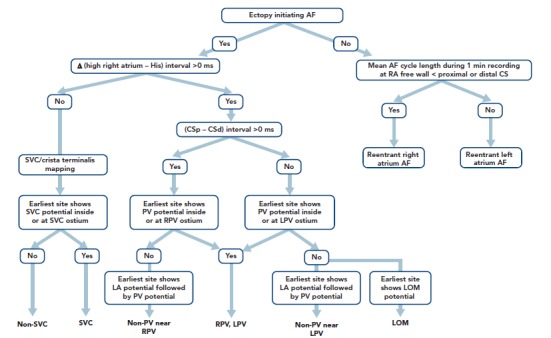

Localisation of AF triggers is important for the catheter ablation of AF. If it is suspected that the trigger is based in the LA, a decapolar catheter should be inserted into the CS via the internal jugular vein and a circular mapping catheter placed in the LA using a transseptal approach. If the initiator is likely to be in the RA, a duodecapolar catheter can be placed from the crista terminalis to the distal SVC for the simultaneous mapping of the right PVs, crista terminalis and SVC. Endocardial activation timing from the high RA, His bundle and distal/proximal portion of the CS can be used to predict non-PV ectopy (Figure 1).[2,4–7,32–34] It is 100 % accurate in discriminating ectopy from the SVC or upper portion of the crista terminalis from PV ectopy.[32–34,62] The interatrial septum should be the suspected initiator in cases with a monophasic positive narrow P wave in lead V1 or a relatively short activation time (≤15 ms) preceding P wave onset during ectopy. Simultaneous mapping of the right- and left-sided interatrial septum should be performed to avoid any misdiagnosis.[32–34,63,64]

Figure 1: Stepwise Algorithm for the Localisation of Non-pulmonary Vein AF Initiators.

Δ (high right atrium – His) represents the time interval from the high right atrial electrogram onset to the onset of the His atrial electrogram during sinus beats minus the same interval measured during ectopic atrial activity. CSp – CSd represents the difference in the atrial activation time between the proximal (p) and distal (d) CS atrial electrograms during an ectopic atrial beat. Source: Higa et al., 2006.[32] Reproduced with permission from Elsevier. CS = coronary sinus; LOM = ligament of Marshall; LPV = left pulmonary vein; PV = pulmonary vein; RPV = right pulmonary vein; SVC = superior vena cava.

AF Initiators with Right Atrial Origin

Careful observation of P wave morphology is useful for predicting the approximate location of AF ectopy.[32–34,65] A negative P wave or the presence of a negative component in V1 is predictive of an RA origin of AF initiation. Ectopy originating from the SVC or upper portion of the crista terminalis exhibits upright P waves in the inferior leads; ectopy from the CS ostium produces negative P wave polarity in the inferior leads; and ectopy from the middle portion of the crista terminalis results in biphasic P waves. Negative P waves with a long duration in V1 may be associated with RA free-wall ectopy, including the tricuspid annulus.

If RA AF ectopy is suspected, the use of a duo-decapolar catheter is useful for mapping along the crista terminalis to the SVC.[2,4–7,32–34] Bipolar signals from the proximal portion of the SVC usually exhibit a blunted atrial signal followed by a discrete sharp SVC signal during sinus rhythm.[32–34] The activation sequence of these double potentials is reversed during SVC ectopy. Bipolar signals from the distal part of the SVC usually exhibit double potentials: the first component represents a SVC near-field sharp potential; and the second component, a right superior PV far-field blunted signal. During SVC ectopy, the activation sequence of these double potentials remains unchanged. The activation sequence is reversed during right PV ectopy.

Intracardiac recordings along the crista terminalis also exhibit double potentials during sinus rhythm, with a high-to-low activation sequence.[32–34] During crista terminalis ectopy, the atrial activation sequence of the double potentials is reversed. Noncontact mapping using an EnSite™ Array™ (Abbott) can accurately localise the ectopic foci with discrete depolarisations and clarify crista terminalis gap conduction-related small radius re-entry.[32–34,66]

AF Initiators with Left Atrial Origin

The time interval between the atrial activation of the decapolar catheter in the proximal CS and that in the distal CS is useful for predicting ectopic foci located near the right (>0 ms) or left PV antrum (<0 ms) (Figure 1).[32–34,62] During sinus rhythm, the fusion potentials of a blunt signal and a rapid, deflecting sharp signal can be observed in the areas between the LA posterior wall and the PV antrum. The fusion potential consists of atrial and PV signals and can be found at the earliest activation site during LA posterior or PV antral ectopy. An alternating pattern of atrial and PV potentials can also be seen during ectopy.[6,32–34]

The Marshall ligament has multiple electrical connections to the musculature of the CS, LA posterior free wall and left PV; therefore, it is essential to differentiate a Marshall potential from a left PV or LA posterior free wall potential. A differential pacing method and/or direct recording of the LOM potential by a microelectrode catheter cannulated into the vein of Marshall can distinguish a PV potential from a Marshall potential (Tables 3 and 4).[7,32–34,56,67,68]

According to expert consensus statements, complex fractionated atrial electrogram (CFAE)-targeted ablation after PV isolation is feasible for substrate modification.[69] Interestingly, our laboratory reported a close anatomical relationship between the distribution of CFAEs and non-PV AF initiators. All of the non-PV AF initiators were associated with continuous CFAE sites.[70,71] Recently, the efficacy of a novel self-reference mapping technique using a PentaRay® catheter (Biosense Webster) to localise non-PV triggers originating from the LA has been reported.[72]

Limitations of Mapping

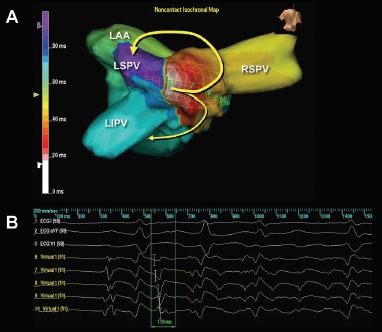

AF ablation can be a challenging and sometimes cumbersome task in cases of unmappable infrequent beats originating from uncommon areas. Activation mapping using fixed multipolar catheters and point-by-point mapping are not efficient for the identification of target ectopies in such cases. Single-beat analysis by noncontact mapping using the Array™ system (Figure 2) or non-invasive body-surface mapping using the CardioInsight™ Mapping Vest system (Medtronic) can be useful tools in these situations.[73]

Figure 2: Mapping of Non-pulmonary Vein Triggers.

(A) An isochronal map during an ectopy-initiated AF. During the ectopy, a focal activation originates from the left atrial middle posterior wall with unidirectional conduction block on the left side of the posterior wall, and the activation wavefront preferentially conducts toward the right pulmonary veins and spreads out to the rest of the left atrium (yellow arrows) followed by AF. (B) The unipolar virtual signals demonstrate “QS” morphology at the origin (virtual 6, from the second beat) and “rS” morphology (virtual 8, from the second beat) at the breakout site. Source: Higa et al., 2008.[73] Reproduced with permission from Dr Jonathan S Steinberg. LAA = left atrial appendage; LIPV = left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV = left superior pulmonary vein; RSPV = right superior pulmonary vein.

Ablation

The earliest bipolar electrogram site with unipolar QS pattern recorded from the origin is the ablation target for non-PV ectopy.[2,4–7,32–34] Ablation of an ectopic focus and/or electrical isolation of an arrhythmogenic thoracic vein can be achieved with the application radiofrequency energy for around 30 seconds with a non-irrigated tip at 50–55 °C or with an irrigated tip at <25–30 W.[2,4–6,32–34] A contact force catheter can be used to create durable transmural lesions. This method has a lower arrhythmia recurrence and a lower incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmias resulting from incomplete ablation due to proarrhythmic lesion gaps. However, caution should be taken to avoid the application of excessive energy and/or contact pressure at the posterior LA wall close to the oesophagus.

Balloon-based cryoablation of the PV antral area, LA posterior wall and persistent left SVC can also be used to isolate arrhythmogenic myocardium. Complications can be minimised by using a cryocatheter at −30 °C to ice map the area near the atrioventricular node following the cryofreezing (−80 °C) of a para-Hisian or CS ostium trigger. Ice mapping can also be used during ablation near the sinus node when targeting SVC or the upper portion of the crista terminalis. Repeated AF induction protocols should be performed after ablation to assess the non-inducibility of the ablated ectopy.[2,4–7,32–34]

Vena Cava Triggers

Electrical disconnection between the arrhythmogenic SVC and RA at the level of the RA–SVC junction is the preferred approach for minimising AF recurrence and SVC stenosis in patients with SVC triggers.[32–34] The aim is to establish bidirectional (entrance and exit) conduction block between the RA and SVC.[5,32–34,47] Circular and basket catheters, and 3D mapping systems including the CARTO® (Biosense Webster), EnSite™ NavX™ Velocity (Abbott), EnSite™ Array™ noncontact mapping system, and Rhythmia HDx™ mapping system with IntellaMap Orion™ catheter (Boston Scientific) can guide SVC isolation.[6,32–34,44–46,74–77]

Persistent left SVC is also a well-recognised trigger site for AF.[19,21,78–85] The connecting musculature means that multiple electrical signals are conducted to the posterolateral LA and middle portion of the CS from the left SVC trigger site. Complete left SVC isolation may be challenging, as it is close to the oesophagus and left phrenic nerve. There have been rare reports of inferior vena cava triggers.[86,87] In these cases, the IVC triggers were successfully eliminated with a focal/isolation strategy.

Interatrial Septal Triggers

Focal ablation of the earliest activation site preceding the onset of AF should be performed until a complete elimination of the ectopy is achieved in patients with interatrial septal triggers. Near-simultaneous atrial activation of the multielectrode catheters located in the high RA, His bundle region and CS ostium can be observed in such cases. Simultaneous mapping of the right and left atrial septum is crucial to successfully locate and ablate this trigger.

Crista Terminalis Triggers

Focal ablation of the earliest activation site in the crista terminalis during ectopy preceding AF onset should be performed until complete elimination of the ectopy initiating AF or >50 % reduction in the amplitude of the initial local electrogram at the ablation site.[6,32–34] A region with transverse gap conduction in the crista terminalis can be an arrhythmogenic source of re-entry and also ectopy initiating AF. Linear ablation of the transverse gap should address both of these problems.[32–34,66] Intracardiac echocardiography can provide real-time monitoring of the anatomical relationship between the crista terminalis and the catheter position during the procedure.

Coronary Sinus Triggers

For patients with a CS trigger, electrical isolation of the arrhythmogenic CS musculature from the atrium by endocardial and/or epicardial ablation under the guidance of a 3D mapping system is preferable.[32–34,71] The aim is to eliminate (entrance block) and/or dissociate (exit block) the CS potential.[88–91] Care must be taken if an inappropriate impedance rise occurs during CS ablation, and the application of radiofrequency energy should be stopped immediately to prevent any steam pops.

Marshall Ligament Triggers

For patients with Marshall ligament triggers, the earliest site with a LOM potential preceding the onset of AF is targeted using an endocardial and/or epicardial approach.[32–34,92] The isolation of both the LOM and left PVs from the LA can be monitored with simultaneous mapping of the LOM and left PV ostia, maximising the chance of a successful procedure.[32–34,56,67,93] Ethanol infusion into an arrhythmogenic vein of Marshall through angioplasty guidewire and balloon catheter in addition to PV isolation has recently been reported to have beneficial outcomes.[94,95]

Left Atrial Triggers

For ectopy from the LA posterior wall, focal ablation of the earliest activation site should be performed (Figure 2). If unsuccessful, a box-shaped linear ablation needs to be added around the ectopy.[6,32–34] Box isolation of the LA posterior wall in combination with PV isolation may be a therapeutic option in cases refractory to extensive focal ablation. The endpoint is complete elimination of the ectopy initiating AF, >50 % reduction in the electrogram amplitude of the ectopic focus, or isolation of the posterior LA wall.[32–34,73]

The left atrial appendage (LAA) has been reported to be a trigger of AF.[96] Due to its large structure, triggers may arise from the LAA ostium, body or tip. Simultaneous mapping of the left superior PV and LAA can differentiate between a near-field sharp and a far-field blunt signals and identify true LAA triggers. Focal ablation can be applied to avoid LAA isolation. LAA isolation is only indicated when the patient can tolerate long-standing anticoagulation or a LAA occlusion device is indicated.

Table 3: Diagnostic Criteria for Non-pulmonary Vein Ectopy Initiating AF.

| Location | Criteria |

|---|---|

| AF initiators from the right atrium |

|

| Inferior vena cava, superior vena cava |

|

| Crista terminalis (CT) |

|

| Coronary sinus ostium |

|

| AF initiators from left atrium |

|

| Left atrial free wall or left atrial appendage |

|

| Ligament of Marshall LOM) |

|

CT = crista terminalis; LOM = ligament of Marshall; PV = pulmonary vein. Source: Higa et al., 2006.[33] Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Table 4: Targets for Ablation of AF Originating from Non-pulmonary Vein Areas.

| AF Initiators | Target Sites | Mapping Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Right Side | ||

| Inferior vena cava, superior vena cava | Breakthrough sites around right atrium–vena cava junction for an isolation | Circular catheter, Array, Grid, PentaRay or Rhythmia |

| Crista terminalis | Earliest crista terminalis activation site for a focal ablation | Unipolar recording with a multipolar catheter, Array, Grid, PentaRay or Rhythmia |

| Coronary sinus | Connection sites between the coronary sinus and atrial musculature for an isolation | Array, PentaRay or Rhythmia |

| Left Side | ||

| Left atrial free wall, septum, appendage, mitral annulus | Earliest activation site for a focal ablation | Unipolar recording with a multipolar catheter, Array, Grid, PentaRay or Rhythmia |

| Ligament of Marshall (LOM) | Earliest LOM potential for a focal ablation | Multipolar recording of triple potentials during ectopy and direct mapping of LOM potentials by microelectrode catheter, Array, Grid, PentaRay or Rhythmia |

| Connection sites between the left atrium and LOM for an isolation | Multipolar recording of triple potentials during ectopy and direct mapping of LOM potentials by a microelectrode catheter, Array, Grid, PentaRay or Rhythmia |

Array = EnSite™ Array™ Noncontact Mapping System (Abbott); Grid = Advisor™ HD Grid Mapping Catheter (Abbott); LOM = ligament of Marshall; PentaRay = PentaRay® Catheter (Biosense Webster); Rhythmia = Rhythmia Mapping System and InntellaMap Orion™ Mapping Catheter (Boston Scientific). Source: Higa et al., 2006.[33] Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Efficacy and Safety of Catheter Ablation

Ablation Outcomes

A relatively high success rate has been demonstrated following the ablation of RA triggers of AF.[6] There is a comparatively higher recurrence rate following the ablation of LA triggers. The average success, recurrence and complication rates are 99.3 %, 18.5 %, and 1.9 %, respectively, for AF originating from the vena cava.[8,43–45,74,78–87,97–111] These rates are 78.0 %, 16.7 %, and 2.4 %, respectively, for AF originating from the Marshall ligament.[6,56,67,68,94,112,113]

A higher incidence of recurrent AF and non-PV AF sources has been reported in patients with metabolic syndrome and obstructive sleep apnoea.[114] Patients who have a greater extent of left atrial delayed enhancement on MRI have a higher recurrence rate after PV isolation, suggesting the existence of AF triggers in non-PV areas.[115]

Managing Complications

Overall complication rates are now relatively low as a result of vast improvements in our understanding of the nature and ablation of non-PV ectopy AF triggers. Injury to the sinus node, atrioventricular node, and phrenic nerve, thoracic vein stenosis, peri-oesophageal damage, gastric hypomotility, and pyloric spasms can all be caused by a non-PV trigger ablation.[116–124]

Complications can be minimised by using a titrated and minimum power setting, short duration of radiofrequency energy, and by monitoring for any sinus rate accelerations, PR or RR interval prolongations and for oesophageal temperature rises. An upstream pacing technique to monitor the phrenic nerve and/or compound muscle action potential can minimise phrenic nerve injury. To reduce the risk of atrio-oesophageal fistula formation, which carries a 60–75 % chance of mortality, surgeons should avoid extensive high-power ablation on the LA posterior and CS walls.[119,121,122,125]

The use of several luminal oesophageal temperature monitoring systems – SensiTherm™ (Abbott) and CIRCA S-Cath™ (CIRCA Scientific) – and protection systems, including oesophageal warming/cooling devices and deviators to avoid thermal injury, has recently been reported.[126–130] Massive air emboli and newly developed thrombi that occur during the ablation procedure can be aspirated.[131]

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that inducing the non-PV ectopic trigger responsible for initiating AF both before and after PV isolation is an indispensable step in both initial and repeat ablation/isolation procedures. Advances in mapping and alternative energy modalities with 3D navigation are likely to play an important role in the ablation of non-PV ectopy. Together, these advances and the systematic identification of the trigger foci and their successful elimination will improve overall AF ablation outcomes.

Clinical Perspective

The mechanisms of paroxysmal AF originating from non-pulmonary vein areas are automaticity, triggered activity, and microreentry.

The diagnosis is made on the basis of a spontaneous onset of the ectopic beats initiating AF during baseline or after provocative manoeuvres.

The earliest activation sites are the targets for focal ablation.

The myocardial sleeve surrounding the ostium of the vena cava is the target for isolation.

Success rates are >99 % for the vena cava and 78 % for the ligament of Marshall.

References

- 1.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen SA, Hsieh MH, Tai CT et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins: Electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological responses, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1999;100:1879–86. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.18.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oral H, Knight BP, Tada H et al. Pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;105:1077–81. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen SA, Tai CT, Yu WC et al. Right atrial focal atrial fibrillation: Electrophysiologic characteristics and radiofrequency catheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:328–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai CF, Tai CT, Hsieh MH et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the superior vena cava: Electrophysiological characteristics and results of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 2000;102:67–74. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin WS, Tai CT, Hsieh MH et al. Catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation initiated by non-pulmonary vein ectopy. Circulation. 2003;107:3176–83. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074206.52056.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai CT, Hsieh MH, Tsai CF et al. Differentiating the ligament of Marshall from the pulmonary vein musculature potentials in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Electrophysiological characteristics and results of radiofrequency ablation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:1493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2000.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah DC, Haissaguerre M, Jais P et al. Nonpulmonary vein foci: Do they exist? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:1631–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beldner SJ, Zado ES, Lin D et al. Anatomic targets for nonpulmonary triggers: Identification with intracardiac echo and magnetic mapping. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1(suppl:):S237. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.03.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki K, Nagata Y, Goya M et al. Impact of non-pulmonary vein focus on early recurrence of atrial fibrillation after pulmonary vein isolation. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1(Suppl:):S203–4. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.03.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada T, Murakami Y, Okada T et al. Non-pulmonary vein epicardial foci of atrial fibrillation identified in the left atrium after pulmonary vein isolation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:1323–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valles E, Fan R, Roux JF et al. Localization of atrial fibrillation triggers in patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation: importance of the carina region. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1413–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo LW, Tai CT, Lin YJ et al. Predicting factors for atrial fibrillation acute termination during catheter ablation procedures: implications for catheter ablation strategy and long-term outcome. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi T, Tsuchiya T, Miyamoto K et al. Characterization of non-pulmonary vein foci with an EnSite array in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2010;12:1698–706. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang HY, Lo LW, Lin YJ et al. Long-term outcome of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation originating from nonpulmonary vein ectopy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:250–8. doi: 10.1111/jce.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Tang C, Zhang Y et al. Origin and ablation of the adenosine triphosphate induced atrial fibrillation after circumferential pulmonary vein isolation: effects on procedural success rate. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:364–70. doi: 10.1111/jce.12362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng H, Dai YY, Jiang RH et al. Non-pulmonary vein foci induced before and after pulmonary vein isolation in patients undergoing ablation therapy for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: incidence and clinical outcome. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2014;15:915–22. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1400146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuroi A, Miyazaki S, Usui E et al. Adenosine-provoked atrial fibrillation originating from non-pulmonary vein foci: the clinical significance and outcome after catheter ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi K, An Y, Nagashima M et al. Importance of nonpulmonary vein foci in catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1918–24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo LW, Lin YJ, Chang SL et al. Predictors and characteristics of multiple (more than 2) catheter ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:1048–56. doi: 10.1111/jce.12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi K, Fukunaga M, Yamaji K et al. Impact of catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with sick sinus syndrome - important role of non-pulmonary vein foci. Circ J. 2016;80:887–94. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasebe H, Yoshida K, Iida M et al. Right-to-left frequency gradient during atrial fibrillation initiated by right atrial ectopies and its augmentation by adenosine triphosphate: Implications of right atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:354–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Di Biase L, Trivedi C et al. Importance of non-pulmonary vein triggers ablation to achieve long-term freedom from paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with low ejection fraction. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santangeli P, Zado ES, Hutchinson MD et al. Prevalence and distribution of focal triggers in persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung Y, Lo LW, Lin YJ et al. Characteristics and long-term catheter ablation outcome in long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation patients with non-pulmonary vein triggers. Int J Cardiol. 2017;241:205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narui R, Matsuo S, Isogai R et al. Impact of deep sedation on the electrophysiological behavior of pulmonary vein and non-PV firing during catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2017;49:51–7. doi: 10.1007/s10840-017-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allamsetty S, Lo LW, Lin YJ et al. Impact of aortic encroachment to left atrium on non-pulmonary vein triggers of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:650–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takigawa M, Takahashi A, Kuwahara T et al. Long-term outcome after catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Impact of different atrial fibrillation foci. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takigawa M, Takahashi A, Kuwahara T et al. Impact of non-pulmonary vein foci on the outcome of the second session of catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:739–46. doi: 10.1111/jce.12681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohanty S, Mohanty P, Di Biase L et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and severe left atrial scarring: comparison between pulmonary vein antrum isolation only or pulmonary vein isolation combined with either scar homogenization or trigger ablation. Europace. 2017;19:1790–7. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappato R, Negroni S, Pecora D et al. Prospective assessment of late conduction recurrence across radiofrequency lesions producing electrical disconnection at the pulmonary vein ostium in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:1599–604. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091081.19465.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higa S, Tai CT, Chen SA. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation originating from extrapulmonary vein areas: Taipei approach. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1386–90. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higa S, Tai CT, Chen SA. Catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation originating from the non-pulmonary vein areas In: In: Huang S, Wood M, editors. Catheter Ablation of Cardiac Arrhythmias. Philadelphia: Elsevier: 2006. pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higa S, Lin YJ, Lo LW . Catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation originating from the non-pulmonary vein areas. In: In: Huang S, Wood M, editors. Catheter Ablation of Cardiac Arrhythmias. Philadelphia: Elsevier: 2011. pp. 265–79. 2nd edn. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangrum JM, Mounsey JP, Kok LC et al. Intracardiac echocardiography-guided, anatomically based radiofrequency ablation of focal atrial fibrillation originating from pulmonary veins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1964–72. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natale A, Pisano E, Beheiry S et al. Ablation of right and left atrial premature beats following cardioversion in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1372–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00774-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jais P, Weerasooriya R, Shah DC et al. Ablation therapy for atrial fibrillation (AF): Past, present and future. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:337–46. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitt C, Ndrepepa G, Weber S et al. Biatrial multisite mapping of atrial premature complexes triggering onset of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1381–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SH, Tai CT, Hsieh MH et al. Predictors of non-pulmonary vein ectopic beats initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: implication for catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1054–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat. 1907;41:189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen YJ, Chen YC, Yeh HI et al. Electrophysiology and arrhythmogenic activity of single cardiomyocytes from canine superior vena cava. Circulation. 2002;105:2679–85. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000016822.96362.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeh HI, Lai YJ, Lee SH et al. Heterogeneity of myocardial sleeve morphology and gap junctions in canine superior vena cava. Circulation. 2001;104:3152–7. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.100836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang KC, Lin YC, Chen JY et al. Electrophysiological characteristics and radiofrequency ablation of focal atrial tachycardia originating from the superior vena cava. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:1034–40. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ooie T, Tsuchiya T, Ashikaga K et al. Electrical connection between the right atrium and the superior vena cava, and the extent of myocardial sleeve in a patient with atrial fibrillation originating from the superior vena cava. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:482–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goya M, Ouyang F, Ernst S et al. Electroanatomic mapping and catheter ablation of breakthroughs from the right atrium to the superior vena cava in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;106:1317–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000033115.92612.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jayam VK, Vasamreddy C, Berger R et al. Electrical disconnection of the superior vena cava from the right atrium. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:614. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ino T, Miyamoto S, Ohno T et al. Exit block of focal repetitive activity in the superior vena cava masquerading as a high right atrial tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:480–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spach MS, Barr RC, Jewett PH. Spread of excitation from the atrium into thoracic veins in human beings and dogs. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30:844–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zipes DP, Knope RF. Electrical properties of the thoracic veins. Am J Cardiol. 1972;29:372–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hashizume H, Ushiki T, Abe K. A histological study of the cardiac muscle of the human superior and inferior venae cavae. Arch Histol Cytol. 1995;58:457–64. doi: 10.1679/aohc.58.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mary-Rabine L, Hordof AJ, Danilo P, Jr et al. Mechanisms for impulse initiation in isolated human atrial fibers. Circ Res. 1980;47:267–77. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.47.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gelband H, Bush HL, Rosen MR et al. Electrophysiologic properties of isolated preparations of human atrial myocardium. Circ Res. 1972;30:293–300. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.30.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ten Eick RE, Singer DH. Electrophysiological properties of diseased human atrium. Circ Res. 1979;44:545–57. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.44.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalman JM, Olgin JE, Karch MR et al. “Cristal tachycardias”: Origin of right atrial tachycardias from the crista terminalis identified by intracardiac echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:451–9. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boineau JP, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB et al. Demonstration of a widely distributed atrial pacemaker complex in the human heart. Circulation. 1988;77:1221–37. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.77.6.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hwang C, Chen PS. Clinical electrophysiology and catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation from the ligament of Marshall. In: In: Chen SA, Haissaguerre M, Zipes DP, editors. Thoracic Vein Arrhythmias: Mechanisms and Treatment. Malden: Blackwell Futura: 2004. pp. 226–84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scherlag BJ, Yeh BK, Robinson MJ. Inferior interatrial pathway in the dog. Circ Res. 1972;31:18–35. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.31.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doshi RN, Wu TJ, Yashima M et al. Relation between ligament of Marshall and adrenergic atrial tachyarrhythmia. Circulation. 1999;100:876–83. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.8.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erlanger J, Blackman JR. A study of relative rhythmicity and conductivity in various regions of the auricles of the mammalian heart. Am J Physiol. 1907;19:125–74. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1907.19.1.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrew LW, Paul FC. Triggered and automatic activity in the canine coronary sinus. Circ Res. 1977;41:435–45. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsuji M, Kato K, Tanaka H et al. Pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a patient with stand-alone unroofed coronary sinus. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2017;3:248–50. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee SH, Tai CT, Lin WS et al. Predicting the arrhythmogenic foci of atrial fibrillation before atrial transseptal procedure: Implication for catheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:750–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frey B, Kreiner G, Gwechenberger M et al. Ablation of atrial tachycardia originating from the vicinity of the atrioventricular node: Significance of mapping both sides of the interatrial septum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:394–400. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marrouche NF, Sippens-Groenewegen A, Yang Y et al. Clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics of left septal atrial tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1133–9. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuo JY, Tai CT, Tsao HM et al. P wave polarities of an arrhythmogenic focus in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation originating from superior vena cava or right superior pulmonary vein. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:350–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin YJ, Tai CT, Liu TY et al. Electrophysiological mechanisms and catheter ablation of complex atrial arrhythmias from crista terminalis: Insight from three-dimensional noncontact mapping. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:1232–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katritsis D, Ioannidis JP, Anagnostopoulos CE et al. Identification and catheter ablation of extracardiac and intracardiac components of ligament of Marshall tissue for treatment ofparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:750–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Polymeropoulos KP, Rodriguez LM, Timmermans C et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: Radiofrequency ablation of a focal atrial tachycardia originating from the Marshall ligament as a trigger for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;105:2112–3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000016168.49833.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:816–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin YJ, Tai CT, Chang SL et al. Efficacy of additional ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms for catheter ablation of nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovascular Electrophysiol. 2009;20:607–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lo LW, Lin YJ, Tsao HM et al. Characteristics of complex fractionated electrograms in non-pulmonary vein ectopy initiating atrial fibrillation / atrial tachycardia. J Cardiovascular Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1305–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matsunaga-Lee Y, Takano Y. A novel mapping technique to detect non-pulmonary vein triggers: a case report of self-reference mapping technique. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2017;4:26–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Higa S, Lin YJ, Tai CT . Noncontact mapping. In: In: Calkin H, Jais P, Steinberg J, editors. A Practical Approach to Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2008. pp. 118–33. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiss C, Willems S, Rostock T et al. Electrical disconnection of an arrhythmogenic superior vena cava with discrete radiofrequency current lesions guided by noncontact mapping. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:1758–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu TY, Tai CT, Lee PC et al. Novel concept of atrial tachyarrhythmias originating from the superior vena cava: Insight from noncontact mapping. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:533–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang BH, Wu MH, Tsao HM et al. Morphology of the thoracic veins and left atrium in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation initiated by superior caval vein ectopy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:411–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.40619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen SA, Tai CT. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation originating from the non-pulmonary vein foci. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:229–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.40665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hsu LF, Jais P, Keane D et al. Atrial fibrillation originating from persistent left superior vena cava. Circulation. 2004;24(109):828–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116753.56467.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elayi CS, Fahmy TS, Wazni OM et al. Left superior vena cava isolation in patients undergoing pulmonary vein antrum isolation: impact on atrial fibrillation recurrence. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1019–23. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu H, Lim KT, Murray C et al. Electrogram-guided isolation of the left superior vena cava for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2007;9:775–80. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsutsui K, Ajiki K, Fujiu K et al. Successful catheter ablation of atrial tachycardia and atrial fibrillation in persistent left superior vena cava. Int Heart J. 2010;51:72–4. doi: 10.1536/ihj.51.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aras D, Cay S, Topaloglu S et al. A rare localization for non-pulmonary vein trigger of atrial fibrillation: persistent left superior vena cava. Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:235–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Abrich VA, Munro J, Srivathsan K. Atrial fibrillation ablation with persistent left superior vena cava detected during intracardiac echocardiography. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2017;3:455–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang S, Pan B, Zou H et al. Cryoballoon ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a case of persistent left superior vena cava. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18:51. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0789-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matsumoto S, Matsunaga-Lee Y, Masunaga N et al. The usefulness of ventricular pacing during atrial fibrillation ablation in a persistent left superior vena cava: A case report. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2018;18:155–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ipej.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mansour M, Ruskin J, Keane D. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the ostium of the inferior vena cava. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:1292–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scavee C, Jais P, Weerasooriya R et al. The inferior vena cava: An exceptional source of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:659–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rotter M, Sanders P, Takahashi Y et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: Coronary sinus tachycardia driving atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;110:e59–60. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138256.14084.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sanders P, Jais P, Hocini M et al. Electrical disconnection of the coronary sinus by radiofrequency catheter ablation to isolate a trigger of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:364–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yamada T, Murakami Y, Plumb VJ et al. Focal atrial fibrillation originating from the coronary sinus musculature. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1088–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rostock T, Lutomsky B, Steven D et al. The coronary sinus as a focal source of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: more evidence for the ‘fifth pulmonary veinb’? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:1027–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tuan TC, Tai CT, Lin YK et al. Use of fluoroscopic views for detecting Marshallb ’s vein in patients with cardiac arrhythmias. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2003;9:327–31. doi: 10.1023/A:1027435208576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Katritsis D, Giazitzoglou E, Korovesis S et al. Epicardial foci of atrial arrhythmias apparently originating in the left pulmonary veins. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:319–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Keida T, Fujita M, Okishige K et al. Elimination of non-pulmonary vein ectopy by ethanol infusion in the vein of Marshall. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1354–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dave AS, Báez-Escudero JL, Sasaridis C et al. Role of the vein of Marshall in atrial fibrillation recurrences after catheter ablation: therapeutic effect of ethanol infusion. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:583–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Di Biase L, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI et al. Left atrial appendage tip: an unusual site of successful ablation after endocardial and epicardial mapping and ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:203–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pastor A, Núñez A, Magalhaes A et al. The superior vena cava as a site of ectopic foci in atrial fibrillation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:68–71. doi: 10.1016/S0300-8932(07)74987-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Higuchi K, Yamauchi Y, Hirao K et al. Superior vena cava as initiator of atrial fibrillation: factors related to its arrhythmogenicity. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chang HY, Lo LW, Lin YJ et al. Long-term outcome of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation originating from the superior vena cava. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:955–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2012.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang PS, Park JG, Pak HN. Catheter ablation for cold water swallowing-induced paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a case report. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:2300–2. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miyazaki S, Taniguchi H, Kusa S et al. Factors predicting an arrhythmogenic superior vena cava in atrial fibrillation ablation: insight into the mechanism. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1560–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Inada K, Matsuo S, Tokutake K et al. Predictors of ectopic firing from the superior vena cava in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2015;42:27–32. doi: 10.1007/s10840-014-9954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Esato M, Nishina N, Kida Y et al. A case of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with a non-pulmonary vein trigger identified by intravenous adenosine triphosphate infusion. J Arrhythm. 2015;31:318–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sugimura S, Kurita T, Kaitani K et al. Ectopies from the superior vena cava after pulmonary vein isolation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Vessels. 2016;31:1562–9. doi: 10.1007/s00380-015-0767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Miranda-Arboleda AF, Munro J, Srivathsan K. Sinus node injury during adjunctive superior vena cava isolation in a patient with triggered atrial fibrillation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2016;16:96–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ipej.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nagase T, Kato R, Asano S et al. AF sustained in only a small area of SVC. Intern Med. 2017;56:2239–40. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.8588-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Trindade MLZHD, Rodrigues ACT, Pisani CF et al. Superior vena cava syndrome after radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017;109:615–7. doi: 10.5935/abc.20170168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Enriquez A, Liang JJ, Santangeli P et al. Focal atrial fibrillation from the superior vena cava. J Atr Fibrillation. 2017;9:1593. doi: 10.4022/jafib.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yagishita A, Yamauchi Y, Miyamoto T et al. Electrophysiological evidence of localized reentry as a trigger and driver of atrial fibrillation at the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2017;3:164–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ebana Y, Nitta J, Takahashi Y et al. Association of the clinical and genetic factors with superior vena cava arrhythmogenicity in atrial fibrillation. Circ J. 2017;82:71–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tanaka Y, Takahashi A, Takagi T et al. Novel ablation strategy for isolating the superior vena cava using ultra high-resolution mapping. Circ J. 2018;82:2007–15. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kashimura S, Nishiyama T, Kimura T et al. Vein of Marshall partially isolated with radiofrequency ablation from the endocardium. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2016;3:120–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Inamura Y, Nitta J, Sato A et al. Successful ablation for non-pulmonary multi-foci atrial fibrillation/tachycardia in a patient with coronary sinus ostial atresia by transseptal puncture and epicardial approach. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2017;3:272–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chang SL, Tuan TC, Tai CT et al. Comparison of outcome in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with versus without the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Oakes RS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG et al. Detection and quantification of left atrial structural remodeling with delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;119:1758–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.811877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee RJ, Kalman JM, Fitzpatrick AP et al. Radiofrequency catheter modification of the sinus node for b “inappropriateb ” sinus tachycardia. Circulation. 1995;92:2919–28. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.10.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Callans DJ, Ren JF, Schwartzman D et al. Narrowing of the superior vena cava-right atrium junction during radiofrequency catheter ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia: Analysis with intracardiac echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1667–70. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Man KC, Knight B, Tse HF et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia guided by activation mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:451–7. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00546-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pappone C, Oral H, Santinelli V et al. Atrio-esophageal fistula as a complication of percutaneous transcatheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;109:2724–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131866.44650.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shah D, Dumonceau JM, Burri H et al. Acute pyloric spasm and gastric hypomotility: an extracardiac adverse effect of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:327–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Black-Maier E, Pokorney SD, Barnett AS et al. Risk of atrioesophageal fistula formation with contact force-sensing catheters. Heart Rhythm. 20;14:1328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.John RM, Kapur S, Ellenbogen KA et al. Atrioesophageal fistula formation with cryoballoon ablation is most commonly related to the left inferior pulmonary vein. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:184–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jhuo SJ, Lo LW, Chang SL et al. Periesophageal vagal plexus injury is a favorable outcome predictor after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1786–93. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Saha SA, Trohman RG. Periesophageal vagal nerve injury following catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a case report and review of the literature. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2015;1:252–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tsao HM, Wu MH, Higa S et al. Anatomic relationship of the esophagus and left atrium: implication for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2005;128:2581–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Carroll BJ, Contreras-Valdes FM, Heist EK et al. Multi-sensor esophageal temperature probe used during radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation is associated with increased intraluminal temperature detection and increased risk of esophageal injury compared to single-sensor probe. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:958–64. doi: 10.1111/jce.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Koranne K, Basu-Ray I, Parikh V et al. Esophageal temperature monitoring during radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J Atr Fibrillation. 2016;9:1452. doi: 10.4022/jafib.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tsuchiya T, Ashikaga K, Nakagawa S et al. Atrial fibrillation ablation with esophageal cooling with a cooled water-irrigated intraesophageal balloon: a pilot study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Arruda MS, Armaganijan L, di Biase L et al. Feasibility and safety of using an esophageal protective system to eliminate esophageal thermal injury: implications on atrial-esophageal fistula following AF ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1272–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Parikh V, Swarup V, Hantla J et al. Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of a novel preshaped nitinol esophageal deviator to successfully deflect the esophagus and ablate left atrium without esophageal temperature rise during atrial fibrillation ablation: The DEFLECT GUT study. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kuwahara T, Takahashi A, Takahashi Y et al. Clinical characteristics of massive air embolism complicating left atrial ablation of atrial fibrillation: lessons from five cases. Europace. 2012;14:204–8. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]