Abstract

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by bacteria of the genus Brucella. Brucella melitensis, Brucella abortus, and Brucella suis are the most pathogenic species of this genus causing the majority of human and domestic animal brucellosis. There is a need to develop a safe and potent subunit vaccine to overcome the serious drawbacks of the live attenuated Brucella vaccines. The aim of this work was to discover antigen candidates conserved among the three pathogenic species. In this study, we employed a reverse vaccinology strategy to compute the core proteome of 90 completed genomes: 55 B. melitensis, 17 B. abortus, and 18 B. suis. The core proteome was analyzed by a metasubcellular localization prediction pipeline to identify surface-associated proteins. The identified proteins were thoroughly analyzed using various in silico tools to obtain the most potential protective antigens. The number of core proteins obtained from analyzing the 90 proteomes was 1939 proteins. The surface-associated proteins were 177. The number of potential antigens was 87; those with adhesion score ≥ 0.5 were considered antigen with “high potential,” while those with a score of 0.4–0.5 were considered antigens with “intermediate potential.” According to a cumulative score derived from protein antigenicity, density of MHC-I and MHC-II epitopes, MHC allele coverage, and B-cell epitope density scores, a final list of 34 potential antigens was obtained. Remarkably, most of the 34 proteins are associated with bacterial adhesion, invasion, evasion, and adaptation to the hostile intracellular environment of macrophages which is adjusted to deprive Brucella of required nutrients. Our results provide a manageable list of potential protective antigens for developing a potent vaccine against brucellosis. Moreover, our elaborated analysis can provide further insights into novel Brucella virulence factors. Our next step is to test some of these antigens using an appropriate antigen delivery system.

1. Introduction

Brucellosis is a global zoonotic infectious disease caused by bacteria of the genus Brucella. The disease is a serious public health threat worldwide, particularly in the developing countries of Central Asia, Africa, South America, and the Mediterranean region [1]. Brucellosis affects mammals, causing abortion and infertility in affected animals. Infection can spread from animals to humans mainly via ingestion of unpasteurized milk or dairy products and, to a lesser extent, via direct contact with infected animals [2]. In humans, brucellosis can cause a severe febrile disease with various clinical complications ranging from mild to severe symptoms including undulant fever, joint pain arthritis, endocarditis, and meningitis [3–5]. Brucella is a genus of Gram-negative facultative intracellular bacteria that belongs to the class Alphaproteobacteria. Currently, the genus consists of 10 species that are classified based on their host preferences [6]. Although several Brucella species are potentially zoonotic agents, Brucella melitensis (B. melitensis), Brucella abortus (B. abortus), and Brucella suis (B. suis) are considered the most pathogenic Brucella species that have a serious impact on public health and the livestock industry [7, 8].

The strategy used to control brucellosis depends mainly on the massive vaccination of domestic animals to prevent disease spread to healthy animals and to humans. Typically, after achieving a very low prevalence rate in domestic animals (below 1%), a strict surveillance strategy can be applied to get rid of infected animals [9, 10]. Currently, there are only a few vaccines that are used to control brucellosis in animals such as B. abortus strains S19 and RB51, B. melitensis strains Rev.1 and M5, and B. suis strain S2 [11]. Almost all these vaccines are live attenuated strains derived by in vitro serial passages from field strains. Despite their extensive global use, these live attenuated vaccines suffer from various drawbacks, such as pathogenicity to humans and residual virulence in animals, which can cause abortion, orchitis, and infertility [12, 13]. Moreover, it is difficult to differentiate infected animals from vaccinated animals by serological tests. These drawbacks have prompted several research groups to attempt the development of safer subunit vaccines. Two conditions are essential to design a good subunit vaccine: first is the selection of appropriate protective antigens, and second is the selection of a safe and efficient vehicle to deliver these antigens to evoke a protective immune response.

During the last two decades, a number of Brucella antigens have been identified, such as Omp16, Omp19, Omp25, Omp31, SurA, Dnak, trigger factor (TF), ribosomal protein L7L12, bacterioferritin (BFR) P39, and lumazine synthase BLS [14–21]. These antigens were selected based on empirical screening approaches that are typically laborious and expensive and require strict safety precautions and particular lab facilities, as the relevant species of Brucella are classified as biosafety level 3 microorganisms. This insufficiency of the empirical methods represents a great need for a rational and comprehensive approach to discover potential antigen candidates that can be used to develop a safe and effective anti Brucella vaccine.

In contrast to the conventional vaccine development approaches that require cultivation and extensive empirical screening, the reverse vaccinology (RV) approach is an interesting in silico approach to identify protective antigens using pathogen genomic data. The method was first developed by Rappuoli and Pizza et al. to discover protective antigens of serogroup B meningococcus [22, 23]. Since then, RV has been implemented to identify protective antigens of numerous pathogens [24, 25]. Two studies have applied RV to identify Brucella antigens [26, 27]. A major limitation of these studies is that they performed RV analysis using only one strain, namely, B. melitensis 16M. Moreover, they employed inadequate antigen selection criteria. Due to the interstrain gene content diversity, it has become crucial to analyze several strains of a given bacterial species or genus to identify the core genome that contains the desired universal protective antigens [28].

In this study, we aimed to discover potential antigen candidates that are conserved among B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis, which are the Brucella species associated with human and domestic animal disease. Our RV approach is an improved version based on determining the core genes of an extensive number of genomes from the three aforementioned Brucella species, followed by a rational antigen selection strategy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to combine pan-genome and reverse vaccinology approaches to identify potential protective antigen that can be used to develop a universal vaccine against the three most pathogenic Brucella species.

2. Materials and Methods

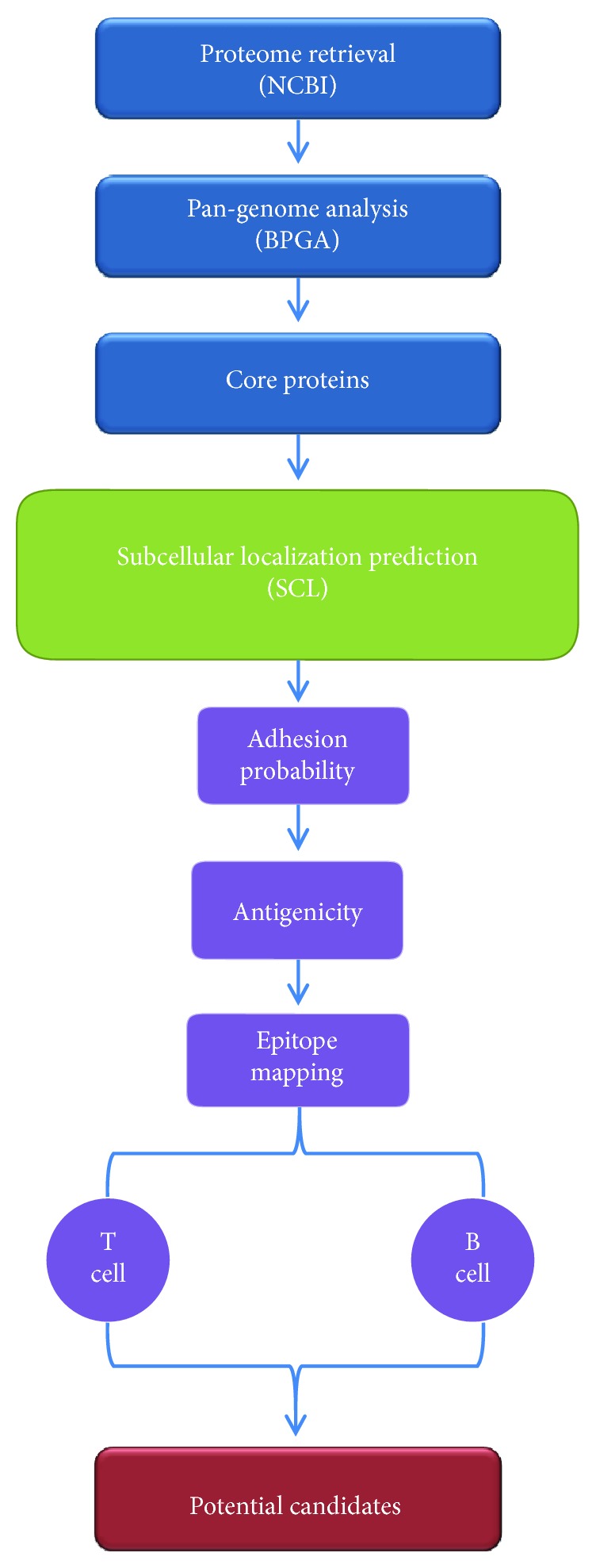

Our in silico antigen prediction protocol is depicted in Figure 1. In the first phase, the retrieved proteomes were analyzed to extract the core proteome (the set of homologous proteins that are present in all analyzed strains of the three Brucella species). The identified core proteome is subsequently analyzed using a subcellular localization prediction pipeline to identify outer membrane and periplasmic proteins. In the last stage, we employed various rigorous filters to prioritize proteins based on features that are strongly associated with protective antigenicity, including adhesion, overall protein antigenicity, and density of B cell and T-cell epitopes. Unless otherwise specified, the default parameters were used for all prediction tools.

Figure 1.

A schematic flow diagram of the reverse vaccinology protocol applied in this study to select potential vaccine candidates of the three Brucella species.

2.1. Data Retrieval

The full multi-FASTA format protein sequences of 55 B. melitensis, 17 B. abortus, and 18 B. suis genomes were downloaded from the Microbial Genomes Resources-NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome) (as of March 2018). Accession numbers, strain names, and number of proteins are shown in Supplementary File 1.

2.2. Pan-Genome Analysis

In order to identify the core proteins, the 90 proteomes were analyzed by the Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis (BPGA) tool using the default parameters [29]. In the input preparation for clustering step, option number 4 (use any protein FASTA files) was chosen. To ensure fast and accurate clustering, BPGA uses USEARCH as a default protein clustering tool with an identity cut off = 50%.

2.3. Subcellular Localization (SCL)

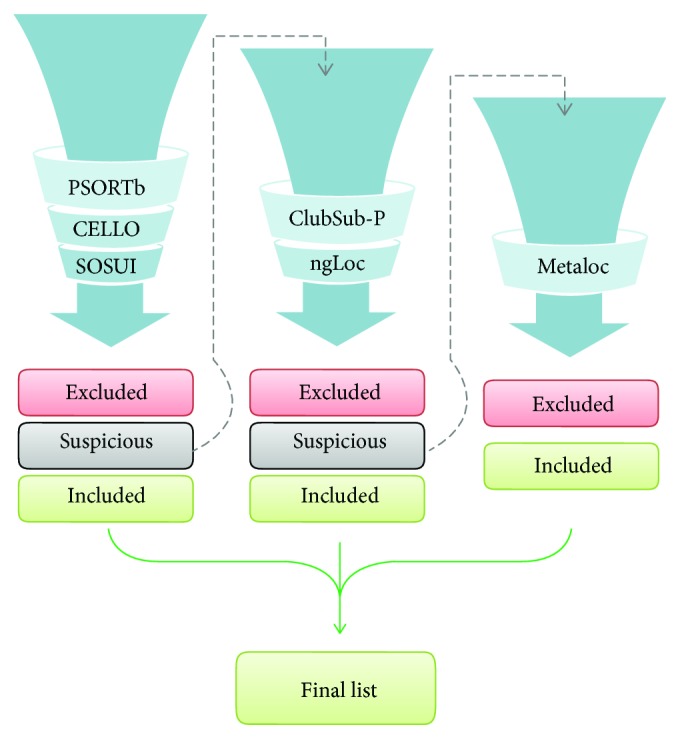

Next, the core proteome was analyzed to predict outer membrane and periplasmic proteins. In this step, a previously developed homemade pipeline for SCL prediction was performed (Y. Ashhab, unpublished data). The pipeline employs different SCL prediction tools in three phases of positive and negative selections (Figure 2). Positive selection was performed for outer membrane (OM) and/or periplasmic (P) proteins. Negative selection was performed for inner membrane (IM), cytoplasmic (CYT), and extracellular (EX) proteins.

Figure 2.

General workflow of our subcellular localization prediction pipeline. A total of 6 tools were applied to the core proteins (1939 proteins) that resulted from pan-genome analysis. The process starts with first group of tools consisting of PSORTb, CELLO, and SOSUI. The proteins with uncertain prediction have to move to the second phase to be analyzed by another two tools, namely, ClubSub-P and ngLoc. The uncertain proteins resulting from the second phase are subjected to the final prediction tool MetaLoc.

The three tools used in the first phase were as follows: PSORTb v3.0.2, CELLO v.2.5, and SOSUI-GramN [30–32]. In this stage, the positive selection was implemented for proteins that were predicted as OM or P by at least two of the three tools and were therefore included. Negative selection was implemented for proteins that were predicted as IM, EX, or CYT by at least two of the three tools and were therefore excluded. Proteins that were predicted with “unknown” subcellular location by at least one of the three tools and OM and/or P by one of the three tools were considered uncertain proteins and were subjected to the second phase of selection. The two tools used in the second phase of selection were as follows: ClubSub-P and ngLoc [33, 34]. Again, resulting proteins were divided into three categories. Positive selection was implemented for proteins that were predicted as OM or P by at least one of the two tools and were therefore included. Negative selection was implemented for proteins that were predicted as IM, EX, or CYT by at least one of the two tools and were therefore excluded. Proteins predicted with “unknown” subcellular location by one of the two tools were defined as uncertain. These uncertain proteins were subjected to a third phase of selection with the metaprediction tool, MetaLoc [35]. Proteins in this final step were divided into two categories: included for OM and P or excluded for the other sites. Included proteins from the three phases were collected for further analysis.

2.4. Adhesion Probability

Adhesion probability of the surface-associated proteins that summed up from the SCL prediction was predicted by Vaxign tool [36]. Proteins with an adhesion score higher than 0.5 were selected for further analysis.

2.5. Protein Antigenicity

Antigenicity of surface-associated proteins was predicted using two tools: AntigenPro which computed antigenicity based on amino acid sequence features [37] and VaxiJen which computed antigenicity based on physicochemical properties of amino acid sequence [38].

2.6. T-Cell Epitope Prediction

Surface-associated proteins were also subjected to sequential epitope mapping in order to indicate their ability to bind to immune cells. T-cell epitopes were predicted for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II, and the number of potential binding alleles for each protein was determined. ProPred1, and ProPred were used for MHC class I and MHC class II epitopes, respectively [39, 40]. The epitope density in a given protein was calculated for each class of MHC by dividing the number of predicted epitopes over the length of that given protein. In addition, epitope coverage was calculated by dividing the number of alleles with positive predictions over the total number of analyzed alleles.

2.7. B-Cell Epitope Prediction

BCPred and AAPred were used for B-cell epitope prediction [41, 42]. Using the default parameters, epitopes with a score ≥ 0.8 were accepted. The density of the B-cell epitope for a given protein was calculated by dividing the number of predicted B-cell epitopes over the protein length.

2.8. Prioritization of Protective Antigens

In this step, a cumulative score for the proteins with adhesion score ≥ 0.5 was calculated using the prediction scores of protein antigenicity, MHC-I and MHC-II epitope densities, allele coverage for both classes of MHC, and B-cell epitope density. The score for each feature was normalized to “1” as the highest possible value and “0” as the lowest possible value. The protein antigenicity score was the average of the two tools: VaxiJen score and AntigenPro score. The B-cell epitope density score was the average density of the two tools: AAPred and BCPred.

2.9. Exclusion of Dubious Proteins

Proteins that show significant homology to host proteins or proteins that have low molecular weight were excluded from the final list. To remove proteins with significant homology to host protein sequences, the selected antigens were subjected to homology search against proteomes using BLASTp tool at https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov with the following parameters: database: reference proteins (refseq_protein); organisms: human, sheep, goat, cattle, and pig; and E-value cutoff: 0.001. Antigens that show ≥35% identity to any host protein were excluded. Molecular weight of small proteins was estimated using ExPASy tool [43]. Proteins having a molecular weight of <10 kDa were excluded.

2.10. Protein Annotation and Domain Search

In addition to the one-line annotation description provided by NCBI, we performed a thorough manual annotation to determine the most likely biological function assigned to the selected antigens. For this purpose, we used the following protein annotation servers: Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG [44–46]. Furthermore, the conserved domain search was predicted using BLAST CD-search tool. BOCTOPUS 2 was used to predict the topology of transmembrane beta-barrel proteins [47].

3. Results

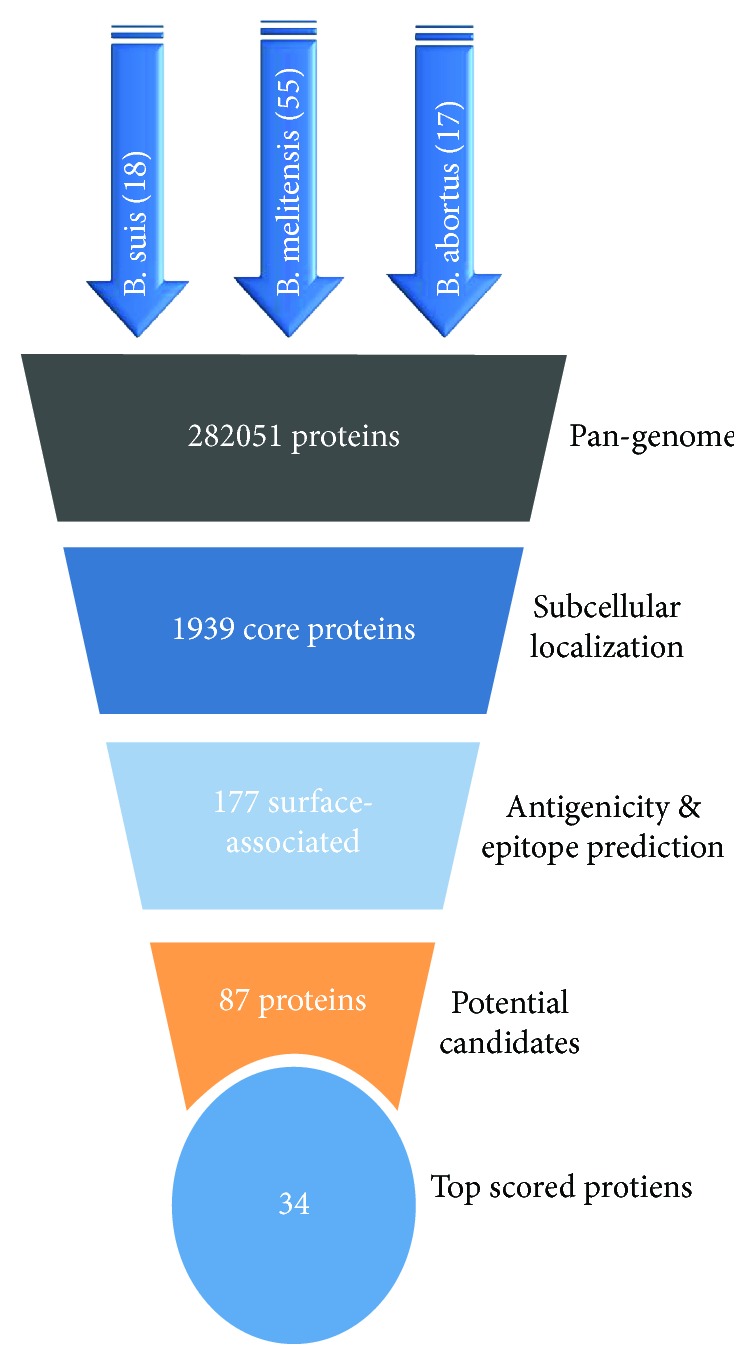

Results of our reverse vaccinology analysis to identify potential antigen candidates that can be used to develop a universal vaccine against Brucella are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of the resultant proteins in each step of our vaccine candidate selection. The total number of analyzed proteins was 282051, the pan-genome analysis resulted in 1939 core proteins. Next, the SCL prediction pipeline resulted in 177 proteins. The number of potential protein candidates was 87, and finally the antigens with the top cumulative antigenicity score were 34.

3.1. Pan-Genome Analysis

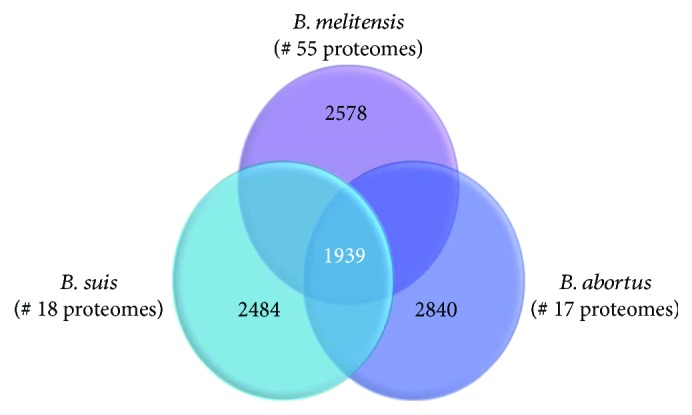

Core proteins were initially identified for each species alone then for the three species together. The number of core proteins for the 17 strains of B. abortus was 2840, while for the 55 strains of B. melitensis was 2578, and for the 18 strains of B. suis was 2484. The number of core proteins for all 90 proteomes of the three species was 1939. Figure 4 shows a Venn diagram of core proteins for the three species.

Figure 4.

This Venn diagram shows the results of the pan-genome analysis of the three Brucella species. The numbers of genomes for each species are indicated. The number of core proteins for each species is shown in each corresponding circle, while the number of core proteins common for all the three species is shown in the intersection area.

3.2. Subcellular Localization (SCL)

From the 1939 core proteins, the surface-associated proteins were selected by our SCL prediction pipeline as shown in Figure 2. In the first phase, 151 proteins were included, 1639 were excluded, and 149 were labeled uncertain. These 149 proteins were subjected to the second phase of analysis in the pipeline, which excluded 104 proteins and included 16 proteins. The rest 29 uncertain proteins were subjected to the final phase of analysis. Of these 29 proteins, 19 were excluded, and 10 were included. Thus, the total number of proteins included from the three phases was 177 proteins, making up the final list of surface-associated proteins (see Supplementary File 2).

3.3. Prioritization of Protective Antigens

As adhesion capacity was shown to be a key feature common to many experimentally verified protective antigens [48], we decide to use adhesion scores, produced by Vaxign, to scale the 177 surface-associated proteins in a descending order. The proteins with an adhesion score ≥ 0.5 (38 proteins) were considered antigens with “high potential,” while those with an adhesion score between 0.4 and 0.5 are considered antigens with “intermediate potential” (see Supplementary File 3). The 38 proteins with high potential were ranked based on a cumulative score that was derived from protein antigenicity, density of MHC-I and MHC-II epitopes, MHC allele coverage, and B-cell epitope density scores (Table 1). For the detailed score calculation, see Supplementary File 4. Of these 38 high-potential proteins, cytochrome c was excluded to avoid autoimmune response because of its homology to host proteins. In addition, 3 proteins with low molecular weight (6.7 kDa, 7.9 kDa, and 9.4 kDa) were excluded because proteins with a molecular weight < 10 kDa are poorly immunogenic [49].

Table 1.

High-potential protein list, with their adhesion score, cumulative results, and consensus annotation resulting from Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG tools. The shown biological function is extracted from protein family databases as well as the indicated literature in the last column.

| Protein ID (NCBI) | Length (aa) | Single-line annotation (NCBI) | Adhesion score | Cumulative score of 5 | Annotation note (by Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG) | Domains (CD-search) | No. of β sheet strands | Biological functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP_004684144.1 | 274 | Porin family protein | 0.59 | 4.56 | Porin opacity type (Pannzer), heat-resistant agglutinin 1 (eggNOG) | LomR | 8 | Small solute transport, colonization, and adhesion | [64, 90] |

| WP_002964666.1 | 227 | OmpW family protein | 0.55 | 4.52 | OmpW family outer membrane protein (Pannzer, eggNOG), uncharacterized outer membrane protein y4mB (Blannotator) | OmpW | 8 | Stress response, small solute transport, and bacterial colonization | [64, 69, 91] |

| WP_002969562.1 | 155 | Hypothetical protein | 0.54 | 4.5 | Not determined | No domain hits | ND | ||

| WP_002966849.1 | 280 | DUF1849 domain-containing protein | 0.6 | 4.5 | ATP/GTP-binding site domain-containing protein A (Pannzer), DUF1849 domain-containing protein (eggNOG) | DUF1849 | Uptake of organic nutrient | ||

| WP_002964611.1 | 351 | DUF1176 domain-containing protein | 0.54 | 4.44 | DUF1176 domain-containing protein (eggNOG) | DUF1176 | ND | ||

| WP_004690357.1 | 284 | Porin family protein | 0.55 | 4.42 | Heat-resistant agglutinin 1 (Pannzer, eggNOG), uncharacterized protein BRA0921/BS1330_II0913 (Blannotator) | LomR | 8 | Small solute transport, colonization, and adhesion | [64, 90] |

| WP_004681227.1 | 238 | Type IV secretion system protein VirB1 | 0.66 | 4.38 | Type IV secretion system protein VirB 1 (Pannzer, Blannotator), conjugal transfer protein (eggNOG) | Lysozyme-like superfamily | Adaptation to intracellular environment | [76, 92] | |

| WP_002966226.1 | 182 | Hypothetical protein | 0.54 | 4.38 | UPF0423 protein BAB2_0840 (Blannotator), pathogen-specific membrane antigen (Pannzer), periplasmic protein (eggNOG) | Tpd iron transport |

Iron acquisition and virulence | [93, 94] | |

| WP_002963597.1 | 121 | Hypothetical protein | 0.5 | 4.37 | Membrane-bound lysozyme inhibitor of C-type lysozyme (by Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG) | MliC | Immune evasion and colonization/virulence factor | [95] | |

| WP_004688070.1 | 192 | Hypothetical protein | 0.59 | 4.32 | Not determined | No domain hit | ND | ||

| WP_002966502.1 | 126 | Hypothetical protein | 0.62 | 4.32 | Outer membrane lipoprotein omp10 (by Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG) | No domain hit | Virulence | [65] | |

| WP_002964322.1 | 329 | Hypothetical protein | 0.59 | 4.23 | 31 kDa transporter (Blannotator), alkanesulfonate transporter substrate-binding subunit (Pannzer), trap transporter solute receptor taxi family (eggNOG) | TRAP_TAXI | Nutrient transport, pathogenicity, and colonization | [96] | |

| WP_002971090.1 | 267 | Hypothetical protein | 0.54 | 4.22 | Outer membrane beta-barrel domain protein (Pannzer) | OM_channel superfamily | 10 | Adhesion | [64, 97] |

| WP_004691650.1 | 620 | TonB-dependent receptor | 0.53 | 4.21 | Iron compound TonB-dependent receptor (Pannzer), involved in the active translocation of vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin) across the outer membrane to the periplasmic space. It derives its energy for transport by interacting with the transperiplasmic membrane protein TonB (by similarity) (eggNOG) | BtuB | Iron acquisition and vitamin B12 transport | [93, 94, 98] | |

| WP_002971481.1 | 168 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor BamE | 0.69 | 4.21 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor BamE (Pannzer), smpa omla domain-containing protein (eggNOG) | BamE | Cell envelope biogenesis and OMP assembly | [99] | |

| WP_004683739.1 | 236 | Porin family protein | 0.56 | 4.21 | Autotransporter outer membrane beta-barrel domain-containing protein fragment (Pannzer), hemin-binding protein (eggNOG) | LomR | 8 | Iron acquisition | [64, 90] |

| WP_004691134.1 | 403 | Hypothetical protein | 0.62 | 4.15 | Putative L,D-transpeptidase YafK (Blannotator), pollen allergen Poa pIX/Phl pVI (Pannzer), ErfK ybiS ycfS ynhG family protein (eggNOG) | Yafk | Envelope biogenesis and stress response | [100] | |

| WP_002965482.1 | 439 | Sugar ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 0.55 | 4.11 | ABC-type sugar transport system periplasmic component (Pannzer), extracellular solute-binding protein family 1 (eggNOG) | PBP2_TMBP_like | Uptake of organic nutrient and invasion/virulence | [73] | |

| WP_002964333.1 | 220 | OmpA family protein | 0.56 | 4.09 | Probable lipoprotein YiaD (Blannotator), cell envelope biogenesis protein OmpA (Pannzer), OmpA motb domain protein (eggNOG) | OmpA | Cell envelope biogenesis, adhesion, invasion/intracellular survival, and evasion of host defense | [67] | |

| WP_023080793.1 | 661 | Heme transporter BhuA | 0.51 | 4.05 | Heme transporter BhuA (Blannotator, Pannzer), receptor (eggNOG) | CirA superfamily | Iron acquisition, virulence, and association for bacterial persistence | [93, 94, 101] | |

| WP_002964719.1 | 261 | Porin family protein | 0.57 | 4.04 | 31 kDa outer membrane immunogenic protein (Omp31) (by Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG) | LomR | 8 | Hemin-binding proteins and virulence | [64, 102, 103] |

| WP_002966352.1 | 156 | DUF2271 domain-containing protein | 0.7 | 4.02 | Tat pathway signal protein (Pannzer), predicted periplasmic protein (DUF2271) (eggNOG) | DUF2271 | ND | ||

| WP_004690579.1 | 429 | Cell wall hydrolase | 0.51 | 4 | Cell wall hydrolase (Pannzer, eggNOG) | CwlJ | Cell envelope biogenesis | [104] | |

| WP_004683944.1 | 212 | Porin family protein | 0.62 | 3.98 | Omp 25 (Pannzer), membrane (eggNOG) | LomR | 8 | Virulence and adhesion | [64, 97, 105] |

| WP_011068938.1 | 792 | LPS-assembly protein LptD | 0.5 | 3.93 | LPS-assembly protein LptD (Pannzer), involved in the assembly of LPS in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane. Determines N-hexane tolerance and is involved in outer membrane permeability. Essential for envelope biogenesis (by similarity) (eggNOG) | LptD | Cell envelope biogenesis | [106] | |

| WP_002967296.1 | 166 | BA14K family protein | 0.6 | 3.92 | Immunoreactive BA14K (Pannzer, eggNOG) | BA14K | Lectin-like activity and virulence | [81, 82] | |

| WP_002964622.1 | 170 | BA14K family protein | 0.58 | 3.92 | Glutelin (Pannzer), BA14K (eggNOG) | BA14K | Lectin-like activity and virulence | [81, 82] | |

| WP_004683466.1 | 213 | Membrane protein | 0.55 | 3.9 | 25 kDa outer membrane immunogenic protein Omp 25 (Blannotator, Pannzer), membrane (eggNOG) | LomR | 8 | Virulence and adhesion | [64, 97, 105] |

| WP_002963776.1 | 115 | DUF2147 | 0.6 | 3.89 | sn-Glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein (Pannzer), uncharacterized protein conserved in bacteria (DUF2147) (eggNOG) | COG4731 | Nutrient transport and invasion/virulence | [73] | |

| WP_004681306.1 | 367 | Iron ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 0.51 | 3.88 | Periplasmic binding ABC transporter (Pannzer), solute-binding protein (eggNOG) | AfuA | Iron acquisition and invasion/virulence | [73] | |

| WP_002964998.1 | 177 | Hypothetical protein | 0.67 | 3.72 | Outer membrane lipoprotein omp19 (by Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG) | Inh | Protease inhibitor and alters the outer membrane properties | [65, 107] | |

| WP_002964530.1 | 287 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor BamD | 0.52 | 3.69 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor BamD (Blannotator, Pannzer), part of the outer membrane protein assembly complex, which is involved in assembly and insertion of beta-barrel proteins into the outer membrane (eggNOG) | BamD | Cell envelope biogenesis, OMP assembly, and required for bacterial viability | [99] | |

| WP_006278325.1 | 261 | Hypothetical protein | 0.5 | 3.69 | Proline-rich region: proline-rich extensin (Pannzer) | DNA_pol3_gamma3 superfamily | ND | ||

| WP_002963780.1 | 216 | Hypothetical protein | 0.7 | 3.58 | Not determined | No domain hit | ND |

Among the 34 proteins classified as antigens with “high potential,” 15 were annotated as hypothetical or unknown function. To gain more insight into the biological functions of these proteins, the 34 proteins were manually annotated using various protein annotation and conserved domain searching tools. The number of proteins with unknown function decreased from 15 to 4 (Table 1). Our domain analysis showed that LomR is a frequently found domain among the antigens with high potential. This domain is a classical domain associated with many outer membrane proteins with transmembrane β-barrel scaffold that belongs to Gram-negative porin superfamily. The results of protein annotation were analyzed to identify any biological pattern that may be associated to the predicted antigens. Although there are little resources to investigate gene ontology of Brucella proteins, the 34 high-potential antigens tend to be associated with certain biological processes, including transmembrane transport (especially ions, iron, and small organic nutrients), membrane assembly, cell adhesion, and pathogenesis (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Brucellosis is a global zoonotic infection with a devastating economic impact on livestock sector and public health in many developing countries [50]. There is an unmet need to develop safe and efficient vaccine to fight brucellosis. This need was addressed in 2017 by launching a global prize competition of 30 million US dollars for developing a safe and efficient vaccine against Brucellosis (https://brucellosisvaccine.org). The first step in developing such a vaccine would be to determine the protective antigens of these bacteria. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine a set of universal and protective antigens that can be used to develop a vaccine against the three most pathogenic species of Brucella (B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis) that are responsible for most cases of brucellosis among domestic animals and humans. We have combined a pan-genome analysis with rational selection steps of reverse vaccinology to determine a manageable shortlist of Brucella antigens. We identified 34 potential cross-protective antigens from 90 complete proteomes covering the three species.

Although two recent studies have published their pan-genome analysis results of Brucella [51, 52], we decided to perform our own pan-genome analysis because these two studies were performed with a relatively limited number of genomes to study the variation and relatedness among almost all species of Brucella, while our objective was to identify the core genome for B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis.

A critical factor in applying a successful RV approach is to have a good understanding of the natural immune response to the pathogen of interest. In the case of Brucella infection, immunity is achieved by triggering both cellular and humoral mechanisms. Cell-mediated immunity plays a critical role in protection against these intracellular bacteria, and it is mainly mediated by Th1 response [53]. On the other hand, passive immunization of animals with antibodies from immunized animals provides protection against Brucella infection [54–56]. Several studies have shown that surface-associated antigens of Gram-negative bacteria are essential to confer not only protective humoral immunity but also cell-mediated immunity against intracellular bacteria [57–59]. Therefore, our first RV filter was to identify outer membrane and periplasmic proteins of Brucella. Instead of using a single tool to identify these surface-associated proteins, we used a home-made pipeline which outperforms the currently available SCL prediction tools (Y. Ashhab, unpublished data). Our pipeline minimizes the possibility of excluding proteins that are assigned with unknown SCL, a scenario common to all SCL prediction tools.

In addition to surface-associated localization, we endeavor to use a feature that is strongly associated to protective immune response. Ong et al. investigated a large group of protective bacterial antigens to reveal the most prominent biological features shared among these proteins. They found that the two most important features shared among protective antigens of Gram-negative bacteria are adhesion and association with cell surface [48]. Consequently, after predicting the list of surface-associated proteins (177 proteins), adhesion capability was predicted and used to rank these proteins.

It has been proven that proteins with high epitope density have significantly greater immunogenicity [60, 61]. Accordingly, proteins with high density of predicted epitopes are more potential vaccine candidates. Despite the growing numbers of immunobioinformatic tools that can predict MHC class I- and class II-binding peptides, these tools are almost exclusive to human and mouse MHC alleles. Unfortunately, domestic animals, such as sheep, goats, and cows, have limited MHC epitope data and prediction tools. However, we noticed a good agreement between the epitope prediction results of human and cow MHC alleles using ProPred server (see Supplementary File 3). This similar binding behavior would support the validity of our MHC scoring and its contribution to enhance the selection of universal antigens.

We have examined the virulence and pathogenicity of our protein list using VirulentPred, a virulence prediction tool [62], and MP3, a metapathogenicity prediction tool [63], respectively. However, the results of these two tools were not informative to rank the antigens; the majority of the 177 surface-associated proteins gave a positive prediction. Therefore, we decided to exclude these two tools.

In this study, we provide a rational reverse vaccinology approach against the three most clinically important Brucella species. Two previous studies have employed reverse vaccinology to identify antigens of B. melitensis strain 16M [26, 27]. However, these studies suffered from a number of limitations. The major limitation is that they were restricted to one genome and therefore their results cannot be extrapolated either to different strains of B. melitensis or to the different pathogenic species of Brucella. Although the two studies were performed on the same strain of B. melitensis, they have no overlapping in the final list of selected antigens.

In this study, 34 proteins were identified as potential protective antigens that can serve to develop a novel universal vaccine against brucellosis. As 15 of these proteins have been deposited in GenBank without assigned function (11 hypothetical proteins and 4 proteins containing domains of unknown function (DUF)), we decided to perform a thorough in silico analysis to gain more insight on the function of all the 34 proteins. As shown in Table 1, the potential antigens tend to fall into a few categories of biological functions. An interesting protein family under these categories is the outer membrane proteins (OMPs) that possess 8–10 strands of β sheet. Of the 34 proteins, 8 belong to this subfamily of OMPs. Despite their involvement in the transport of small solutes, it was found that small-size OMPs (8–10 β sheet strands) tend to have a key role in adhesion, invasion, and evasion to contribute to the tissue damage and bacterial spread across tissue barriers [64]. Indeed, most of the shortlisted OMPs such as Omp19, Omp25, Omp31, OmpA, and OmpW are associated with Brucella virulence and some of them showed a significant level of immune response when used as subunit vaccines [65–71].

A second interesting group of proteins is related to iron acquisition, including the hypothetical protein “WP_002966226.1,” TonB-dependent receptor “WP_004691650.1,” heme transporter BhuA “WP_023080793.1,” and the iron ABC transporter substrate-binding protein “WP_004681306.1.” The importance of iron for survival and virulence of Brucella is well documented, and targeting proteins essential for iron acquisition is a promising strategy to develop effective bacterial vaccines [72].

A third group of proteins is the ABC transporters. This family of transporters is essential to secure uptake of various vital nutrients that cannot be produced by Brucella. It is believed that the ABC transporter proteins play a role in Brucella survival within the host during its infectious life cycle [73]. Furthermore, it has been reported that the ABC proteins are able to induce immunity, making them potential vaccine targets [74, 75].

An interesting identified candidate is VirB1, which is a component of the type IV secretion system (T4SS) of Brucella spp. This secretion system in Brucella is a well-known virulence factor, which is responsible for survival, intracellular trafficking, and replication of Brucella inside the infected host cells [76–78]. Using our selection approach, we were able to identify some potential antigens that are periplasmic proteins with critical roles in outer membrane biogenesis and integrity. Among these proteins are BamD and BamE, which are critical components of the β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM) [79]. Another interesting protein is the LPS-assembly protein LptD that is an essential component of the lipopolysaccharide transport (Lpt) machinery [80]. It is plausible that targeting one of these essential outer membrane biogenesis machineries would have a severe effect on bacterial survival.

Among the list of potential antigens, two proteins belong to the BA14K immunoreactive protein family, which is a poorly characterized group of surface antigens. It has been reported that this family can strongly induce both cellular and humoral immune responses [81, 82]. Further investigation is needed to understand the functions of these two factors and their potential as protective antigens.

As our aim was to identify universal antigens conserved among the three pathogenic species (B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis), it is possible that our approach could have missed some interesting species-specific antigens. Although we ranked the 177 surface-associated proteins using adhesion, which is a crucial biological property strongly associated with a significant number of experimentally verified protective antigens, we cannot exclude the possibility that some potential antigens are missed from our “high-potential” 34 antigens. In fact, a few interesting candidates were ranked in the “intermediate-potential” antigens (see Supplementary File 3). Among these interesting candidates are Bp26 and SOD. Bp26, or immunoreactive Omp28, is an antigen protein that is widely described as a potential vaccine candidate [27, 70, 83, 84]. In addition, it has been found to be immunogenic in both goats and humans and it provides a significant protection rate in BALB/c mice [84, 85]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) proteins have been reported in B. abortus and found to be responsible for host macrophage bursts. Thus, it is considered a promising antigen [86]. This antigen has also been found in B. melitensis as an immunodominant protein [87]. Moreover, SOD is considered a potential antigen with promising protective properties [70, 88, 89]. Here, we were able to identify two superoxide dismutases, namely, SOD_Cu-Zn and SOD_Mn within the list of “intermediate-potential” antigens.

It is worth to mention that our extended list of antigens, either with high and/or with intermediate potential, does not contain various cytoplasmic proteins that were previously suggested as possible antigens [15–17]. Among these antigens, lumazine synthase BLS is the most interesting candidate because it showed a good humoral and cell-mediated response and it induces protective immunity in mice [15].

5. Conclusion

Bioinformatics is a strong approach for vaccine candidate discovery as it offers a faster, cheaper, and safer method to identify potential vaccine targets when compared with traditional laboratory identification methods, particularly when dealing with risk group 3 microorganisms such as Brucella. Here, we provide a RV strategy that combines pan-genome analysis with a meta-SCL pipeline, followed by a rational-based selection that can rank surface-associated antigens according to their potential protective immunogenicity. Using our approach, we were able to identify several potential cross-protective candidates. The majority of the top-ranked antigens are strongly associated to bacterial virulence, and, therefore, it is plausible to assume that some of these antigens can form a solid base to design an efficient and safe vaccine against animal and human brucellosis. Further experiments are needed to test immunogenicity and protection level of these proteins.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Asma Altamimi and Ms. Bara'a Altamimi for their technical help and Dr. Eric Dietze and Mrs. Sakina Al-Ashhab for their helpful proofreading of the manuscript. In addition, the authors wish to thank Al-Quds Academy for Scientific Research (QASR) for their generous support to the Brucella vaccine project.

Data Availability

All the data used to support the findings of this study are included within the supplementary information file(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding publication of this paper.

Supplementary Materials

This table contains the strain name, genome accession numbers, and number of proteins of the 90 Brucella genomes used to conduct this study.

This Excel file contains the 177 surface-associated proteins resulted from our SCL prediction pipeline. The prediction results of 6 SCL tools used in the pipeline are shown.

This Excel file shows the 87 proteins: the first 38 proteins (with adhesion score ≥ 0.5) that are considered antigens with “high potential” and the rest 49 proteins (with adhesion score between 0.4 and 0.5) that are considered antigens with “intermediate potential.” The results of overall antigenicity and T- and B-cell epitope densities are also shown.

This Excel file contains the detailed calculation of the immunogenicity cumulative score that was derived from overall protein antigenicity, MHC-I density, MHC-II density, allele coverage, and B-cell density. In addition, it shows the results of conserved domain search and annotation results of the three tools: Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG of the top 34 proteins.

References

- 1.Musallam I. I., Abo-shehada M. N., Hegazy Y. M., Holt H. R., Guitian F. J. Systematic review of brucellosis in the Middle East: disease frequency in ruminants and humans and risk factors for human infection. Epidemiology and Infection. 2016;144(4):671–685. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815002575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbel M. J. Brucellosis in Humans and Animals. World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal M., Gizaw F., Fekadu G., Alemayehu G., Kandi V. Public health and economic importance of bovine brucellosis: an overview. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2017;5(2):27–34. doi: 10.12691/ajeid-5-2-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gortázar C., Ferroglio E., Höfle U., Frölich K., Vicente J. Diseases shared between wildlife and livestock: a European perspective. European Journal of Wildlife Research. 2007;53(4):241–256. doi: 10.1007/s10344-007-0098-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franco M. P., Mulder M., Gilman R. H., Smits H. L. Human brucellosis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007;7(12):775–786. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ficht T. Brucella taxonomy and evolution. Future Microbiology. 2010;5(6):859–866. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smits H. L. Brucellosis in pastoral and confined livestock: prevention and vaccination. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 2013;32(1):219–228. doi: 10.20506/rst.32.1.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seleem M. N., Boyle S. M., Sriranganathan N. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Veterinary Microbiology. 2010;140(3-4):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blasco J. Control and eradication strategies for Brucella melitensis infection in sheep and goats. Prilozi. 2010;31(1):145–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Sancho M., García-Seco T., Domínguez L., Álvarez J. Updates on Brucellosis. InTech; 2015. Control of animal brucellosis—the most effective tool to prevent human brucellosis. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avila-Calderón E. D., Lopez-Merino A., Sriranganathan N., Boyle S. M., Contreras-Rodríguez A. A history of the development of Brucella vaccines. BioMed Research International. 2013;2013:8. doi: 10.1155/2013/743509.743509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adone R., Ciuchini F., Marianelli C., et al. Protective properties of rifampin-resistant rough mutants of Brucella melitensis. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73(7):4198–4204. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4198-4204.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodwin Z. I., Pascual D. W. Brucellosis vaccines for livestock. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2016;181:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira S. C., Splitter G. A. Immunization of mice with recombinant L7L12 ribosomal protein confers protection against Brucella abortus infection. Vaccine. 1996;14(10):959–962. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(96)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velikovsky C. A., Goldbaum F. A., Cassataro J., et al. Brucella lumazine synthase elicits a mixed Th1-Th2 immune response and reduces infection in mice challenged with Brucella abortus 544 independently of the adjuvant formulation used. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71(10):5750–5755. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5750-5755.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mariri A., Tibor A., Mertens P., et al. Induction of immune response in BALB/c mice with a DNA vaccine encoding bacterioferritin or P39 of Brucella spp. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69(10):6264–6270. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6264-6270.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghasemi A., Jeddi-Tehrani M., Mautner J., Salari M. H., Zarnani A.-H. Simultaneous immunization of mice with Omp31 and TF provides protection against Brucella melitensis infection. Vaccine. 2015;33(42):5532–5538. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goel D., Bhatnagar R. Intradermal immunization with outer membrane protein 25 protects Balb/c mice from virulent B. abortus 544. Molecular Immunology. 2012;51(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delpino M. V., Estein S. M., Fossati C. A., Baldi P. C., Cassataro J. Vaccination with Brucella recombinant DnaK and SurA proteins induces protection against Brucella abortus infection in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2007;25(37-38):6721–6729. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassataro J., Velikovsky C. A., de la Barrera S., et al. A DNA vaccine coding for the Brucella outer membrane protein 31 confers protection against B. melitensis and B. ovis infection by eliciting a specific cytotoxic response. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73(10):6537–6546. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6537-6546.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasquevich K. A., Estein S. M., Samartino C. G., et al. Immunization with recombinant Brucella species outer membrane protein Omp16 or Omp19 in adjuvant induces specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as systemic and oral protection against Brucella abortus infection. Infection and Immunity. 2008;77(1):436–445. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01151-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2000;3(5):445–450. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizza M., Scarlato V., Masignani V., et al. Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2000;287(5459):1816–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seib K. L., Zhao X., Rappuoli R. Developing vaccines in the era of genomics: a decade of reverse vaccinology. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(s5):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delany I., Rappuoli R., Seib K. L. Vaccines, reverse vaccinology, and bacterial pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2013;3(5, article a012476) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vishnu U. S., Sankarasubramanian J., Gunasekaran P., Rajendhran J. Novel vaccine candidates against Brucella melitensis identified through reverse vaccinology approach. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology. 2015;19(11):722–729. doi: 10.1089/omi.2015.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez G., Pei J., Mwangi W., Adams L. G., Rice-Ficht A., Ficht T. A. Immunogenic and invasive properties of Brucella melitensis 16M outer membrane protein vaccine candidates identified via a reverse vaccinology approach. PLoS One. 2013;8(3, article e59751) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donati C., Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology in the 21st century: improvements over the original design. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2013;1285(1):115–132. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhari N. M., Gupta V. K., Dutta C. BPGA- an ultra-fast pan-genome analysis pipeline. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep24373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu N. Y., Wagner J. R., Laird M. R., et al. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(13):1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu C. S., Chen Y. C., Lu C. H., Hwang J. K. Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2006;64(3):643–651. doi: 10.1002/prot.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imai K., Asakawa N., Tsuji T., et al. SOSUI-GramN: high performance prediction for sub-cellular localization of proteins in Gram-negative bacteria. Bioinformation. 2008;2(9):417–421. doi: 10.6026/97320630002417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paramasivam N., Linke D. ClubSub-P: cluster-based subcellular localization prediction for Gram-negative bacteria and archaea. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King B. R., Guda C. ngLOC: an n-gram-based Bayesian method for estimating the subcellular proteomes of eukaryotes. Genome Biology. 2007;8(5):p. R68. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnus M., Pawlowski M., Bujnicki J. M. MetaLocGramN: a meta-predictor of protein subcellular localization for Gram-negative bacteria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 2012;1824(12):1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He Y., Xiang Z., Mobley H. L. T. Vaxign: the first web-based vaccine design program for reverse vaccinology and applications for vaccine development. BioMed Research International. 2010;2010:15. doi: 10.1155/2010/297505.297505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng J., Randall A. Z., Sweredoski M. J., Baldi P. SCRATCH: a protein structure and structural feature prediction server. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33:W72–W76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doytchinova I. A., Flower D. R. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8(1):p. 4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh H., Raghava G. P. S. ProPred1: prediction of promiscuous MHC class-I binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(8):1009–1014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh H., Raghava G. P. S. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(12):1236–1237. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J., Liu H., Yang J., Chou K.-C. Prediction of linear B-cell epitopes using amino acid pair antigenicity scale. Amino Acids. 2007;33(3):423–428. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.EL-Manzalawy Y., Dobbs D., Honavar V. Predicting linear B-cell epitopes using string kernels. Journal of Molecular Recognition. 2008;21(4):243–255. doi: 10.1002/jmr.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., et al. The proteomics protocols handbook. Humana Press; 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server; pp. 571–607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kankainen M., Ojala T., Holm L. BLANNOTATOR: enhanced homology-based function prediction of bacterial proteins. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(1):p. 33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koskinen P., Törönen P., Nokso-Koivisto J., Holm L. PANNZER: high-throughput functional annotation of uncharacterized proteins in an error-prone environment. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(10):1544–1552. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huerta-Cepas J., Szklarczyk D., Forslund K., et al. eggNOG 4.5: a hierarchical orthology framework with improved functional annotations for eukaryotic, prokaryotic and viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(D1):D286–D293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayat S., Peters C., Shu N., Tsirigos K. D., Elofsson A. Inclusion of dyad-repeat pattern improves topology prediction of transmembrane β-barrel proteins. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(10):1571–1573. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ong E., Wong M. U., He Y. Identification of new features from known bacterial protective vaccine antigens enhances rational vaccine design. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohanty S. K., Mohanty S. K., Leela K. S. Textbook of Immunology. JP Medical Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mcdermott J. J., Grace D., Zinsstag J. Economics of brucellosis impact and control in low-income countries. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 2013;32(1):249–261. doi: 10.20506/rst.32.1.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sankarasubramanian J., Vishnu U. S., Sridhar J., Gunasekaran P., Rajendhran J. Pan-genome of Brucella species. Indian Journal of Microbiology. 2015;55(1):88–101. doi: 10.1007/s12088-014-0486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang X., Li Y., Zang J., et al. Analysis of pan-genome to identify the core genes and essential genes of Brucella spp. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2016;291(2):905–912. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1154-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitry M.-A., Hanot Mambres D., de Trez C., et al. Humoral immunity and CD4+ Th1 cells are both necessary for a fully protective immune response upon secondary infection with Brucella melitensis. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;192(8):3740–3752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Araya L., Winter A. Comparative protection of mice against virulent and attenuated strains of Brucella abortus by passive transfer of immune T cells or serum. Infection and Immunity. 1990;58(1):254–256. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.254-256.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adone R., Francia M., Pistoia C., Petrucci P., Pesciaroli M., Pasquali P. Protective role of antibodies induced by Brucella melitensis B115 against B. melitensis and Brucella abortus infections in mice. Vaccine. 2012;30(27):3992–3995. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jain L., Rawat M., Ramakrishnan S., Kumar B. Active immunization with Brucella abortus S19 phage lysate elicits serum IgG that protects guinea pigs against virulent B. abortus and protects mice by passive immunization. Biologicals. 2017;45:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barat S., Willer Y., Rizos K., et al. Immunity to intracellular Salmonella depends on surface-associated antigens. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8(10, article e1002966) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bumann D. Identification of protective antigens for vaccination against systemic salmonellosis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bras-Gonçalves R., Petitdidier E., Pagniez J., et al. Identification and characterization of new Leishmania promastigote surface antigens, LaPSA-38S and LiPSA-50S, as major immunodominant excreted/secreted components of L. amazonensis and L. infantum. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2014;24:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu W., Chen Y. H. High epitope density in a single protein molecule significantly enhances antigenicity as well as immunogenicity: a novel strategy for modern vaccine development and a preliminary investigation about B cell discrimination of monomeric proteins. European Journal of Immunology. 2005;35(2):505–514. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sette A., Vitiello A., Reherman B., et al. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. The Journal of Immunology. 1994;153(12):5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garg A., Gupta D. VirulentPred: a SVM based prediction method for virulent proteins in bacterial pathogens. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):p. 62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gupta A., Kapil R., Dhakan D. B., Sharma V. K. MP3: a software tool for the prediction of pathogenic proteins in genomic and metagenomic data. PLoS One. 2014;9(4, article e93907) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McClean S. Eight stranded β-barrel and related outer membrane proteins: role in bacterial pathogenesis. Protein and Peptide Letters. 2012;19(10):1013–1025. doi: 10.2174/092986612802762688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tibor A., Wansard V., Bielartz V., et al. Effect of omp10 or omp19 deletion on Brucella abortus outer membrane properties and virulence in mice. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70(10):5540–5546. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5540-5546.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tadepalli G., Singh A. K., Balakrishna K., Murali H. S., Batra H. V. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Brucella abortus recombinant protein cocktail (rOmp19+ rP39) against B. abortus 544 and B. melitensis 16M infection in murine model. Molecular Immunology. 2016;71:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Confer A. W., Ayalew S. The OmpA family of proteins: roles in bacterial pathogenesis and immunity. Veterinary Microbiology. 2013;163(3-4):207–222. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simborio H. L. T., Reyes A. W. B., Hop H. T., et al. Immune modulation of recombinant OmpA against Brucella abortus 544 infection in mice. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2016;26(3):603–609. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1509.09061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu X.-B., Tian L.-H., Zou H.-J., et al. Outer membrane protein OmpW of Escherichia coli is required for resistance to phagocytosis. Research in Microbiology. 2013;164(8):848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hur J., Xiang Z., Feldman E. L., He Y. Ontology-based Brucella vaccine literature indexing and systematic analysis of gene-vaccine association network. BMC Immunology. 2011;12(1):49–49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martín-Martín A. I., Caro-Hernández P., Sancho P., et al. Analysis of the occurrence and distribution of the Omp25/Omp31 family of surface proteins in the six classical Brucella species. Veterinary Microbiology. 2009;137(1-2):74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cassat J. E., Skaar E. P. Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;13(5):509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosinha G. M. S., Freitas D. A., Miyoshi A., et al. Identification and characterization of a Brucella abortus ATP-binding cassette transporter homolog to Rhizobium meliloti ExsA and its role in virulence and protection in mice. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70(9):5036–5044. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5036-5044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Riquelme-Neira R., Retamal-Díaz A., Acuña F., et al. Protective effect of a DNA vaccine containing an open reading frame with homology to an ABC-type transporter present in the genomic island 3 of Brucella abortus in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2013;31(36):3663–3667. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Issa M. N., Ashhab Y. Identification of Brucella melitensis Rev. 1 vaccine-strain genetic markers: towards understanding the molecular mechanism behind virulence attenuation. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):4884–4891. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Comerci D. J., Martínez-Lorenzo M. J., Sieira R., Gorvel J. P., Ugalde R. A. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus-containing vacuole. Cellular Microbiology. 2001;3(3):159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boschiroli M. L., Ouahrani-Bettache S., Foulongne V., et al. The Brucella suis virB operon is induced intracellularly in macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(3):1544–1549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032514299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dozot M., Boigegrain R. A., Delrue R. M., et al. The stringent response mediator Rsh is required for Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis virulence, and for expression of the type IV secretion system virB. Cellular Microbiology. 2006;8(11):1791–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Konovalova A., Kahne D. E., Silhavy T. J. Outer membrane biogenesis. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2017;71(1):539–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sperandeo P., Martorana A. M., Polissi A. The lipopolysaccharide transport (Lpt) machinery: a nonconventional transporter for lipopolysaccharide assembly at the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017;292(44):17981–17990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.802512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chirhart-Gilleland R. L., Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Jennings S. R., Roop R. M., 2nd Identification and characterization of a 14-kilodalton Brucella abortus protein reactive with antibodies from naturally and experimentally infected hosts and T lymphocytes from experimentally infected BALB/c mice. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66(8):4000–4003. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.4000-4003.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vemulapalli T. H., Vemulapalli R., Schurig G. G., Boyle S. M., Sriranganathan N. Role in virulence of a Brucella abortus protein exhibiting lectin-like activity. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74(1):183–191. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.183-191.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cannella A. P., Tsolis R. M., Liang L., et al. Antigen-specific acquired immunity in human brucellosis: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and vaccine development. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2012;2 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liang L., Leng D., Burk C., et al. Large scale immune profiling of infected humans and goats reveals differential recognition of Brucella melitensis antigens. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4(5, article e673) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang X., Hudson M., Walters N., Bargatze R. F., Pascual D. W. Selection of protective epitopes for Brucella melitensis by DNA vaccination. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73(11):7297–7303. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7297-7303.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gee J. M., Valderas M. W., Kovach M. E., et al. The Brucella abortus Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase is required for optimal resistance to oxidative killing by murine macrophages and wild-type virulence in experimentally infected mice. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73(5):2873–2880. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2873-2880.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang Y., Wang L., Yin J., et al. Immunoproteomic analysis of Brucella melitensis and identification of a new immunogenic candidate protein for the development of brucellosis subunit vaccine. Molecular Immunology. 2011;49(1-2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.He Y. Analyses of Brucella pathogenesis, host immunity, and vaccine targets using systems biology and bioinformatics. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2012;2 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sáez D., Guzmán I., Andrews E., Cabrera A., Onate A. Evaluation of Brucella abortus DNA and RNA vaccines expressing Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene in cattle. Veterinary Microbiology. 2008;129(3-4):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mancini J., Weckselblatt B., Chung Y. K., et al. The heat-resistant agglutinin family includes a novel adhesin from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain 60A. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(18):4813–4820. doi: 10.1128/JB.05142-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hong H., Patel D. R., Tamm L. K., van den Berg B. The outer membrane protein OmpW forms an eight-stranded β-barrel with a hydrophobic channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(11):7568–7577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Den Hartigh A. B., Sun Y.-H., Sondervan D., et al. Differential requirements for VirB1 and VirB2 during Brucella abortus infection. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(9):5143–5149. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5143-5149.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Elhassanny A. E. M., Anderson E. S., Menscher E. A., Roop R. M., II The ferrous iron transporter FtrABCD is required for the virulence of Brucella abortus 2308 in mice. Molecular Microbiology. 2013;88(6):1070–1082. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roset M. S., Alefantis T. G., DelVecchio V. G., Briones G. Iron-dependent reconfiguration of the proteome underlies the intracellular lifestyle of Brucella abortus. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):p. 10637. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Callewaert L., Aertsen A., Deckers D., et al. A new family of lysozyme inhibitors contributing to lysozyme tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4(3, article e1000019) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rosa L. T., Bianconi M. E., Thomas G. H., Kelly D. J. Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters and tripartite tricarboxylate transporters (TTT): from uptake to pathogenicity. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2018;8:p. 33. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fairman J. W., Noinaj N., Buchanan S. K. The structural biology of β-barrel membrane proteins: a summary of recent reports. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2011;21(4):523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liao H., Liu M., Cheng A. Structural features and functional mechanism of TonB in some Gram-negative bacteria-a review. Wei sheng wu xue bao= Acta Microbiologica Sinica. 2015;55(5):529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sikora A. E., Wierzbicki I. H., Zielke R. A., et al. Structural and functional insights into the role of BamD and BamE within the β-barrel assembly machinery inNeisseria gonorrhoeae. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2018;293(4):1106–1119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sanders A. N., Pavelka M. S. Phenotypic analysis of Eschericia coli mutants lacking L, D-transpeptidases. Microbiology. 2013;159(Part_9):1842–1852. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.069211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Paulley J. T., Anderson E. S., Roop R. M. Brucella abortus requires the heme transporter BhuA for maintenance of chronic infection in BALB/c mice. Infection and Immunity. 2007;75(11):5248–5254. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00460-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Delpino M. V., Cassataro J., Fossati C. A., Goldbaum F. A., Baldi P. C. Brucella outer membrane protein Omp31 is a haemin-binding protein. Microbes and Infection. 2006;8(5):1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carroll J. A., Coleman S. A., Smitherman L. S., Minnick M. F. Hemin-binding surface protein from Bartonella quintana. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(12):6750–6757. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6750-6757.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nair N., Vinod V., Suresh M. K., et al. Amidase, a cell wall hydrolase, elicits protective immunity against Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;77:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cloeckaert A., Vizcaíno N., Paquet J.-Y., Bowden R. A., Elzer P. H. Major outer membrane proteins of Brucella spp.: past, present and future. Veterinary Microbiology. 2002;90(1–4):229–247. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chng S.-S., Ruiz N., Chimalakonda G., Silhavy T. J., Kahne D. Characterization of the two-protein complex in Escherichia coli responsible for lipopolysaccharide assembly at the outer membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(12):5363–5368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912872107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Coria L. M., Ibañez A. E., Tkach M., et al. A Brucella spp. protease inhibitor limits antigen lysosomal proteolysis, increases cross-presentation, and enhances CD8+ T cell responses. The Journal of Immunology. 2016;196(10):4014–4029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This table contains the strain name, genome accession numbers, and number of proteins of the 90 Brucella genomes used to conduct this study.

This Excel file contains the 177 surface-associated proteins resulted from our SCL prediction pipeline. The prediction results of 6 SCL tools used in the pipeline are shown.

This Excel file shows the 87 proteins: the first 38 proteins (with adhesion score ≥ 0.5) that are considered antigens with “high potential” and the rest 49 proteins (with adhesion score between 0.4 and 0.5) that are considered antigens with “intermediate potential.” The results of overall antigenicity and T- and B-cell epitope densities are also shown.

This Excel file contains the detailed calculation of the immunogenicity cumulative score that was derived from overall protein antigenicity, MHC-I density, MHC-II density, allele coverage, and B-cell density. In addition, it shows the results of conserved domain search and annotation results of the three tools: Blannotator, Pannzer, and eggNOG of the top 34 proteins.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used to support the findings of this study are included within the supplementary information file(s).