Abstract

Background

Newer antidiabetic drugs, i.e., dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) may exert distinct cardiovascular effects. We sought to explore their impact on vascular function.

Methods

Published literature was systematically searched up to January 2018 for clinical studies assessing the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 RAs, and SGLT-2 inhibitors on endothelial function and arterial stiffness, assessed by flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery and pulse wave velocity (PWV), respectively. For each eligible study, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for FMD and PWV. The pooled MD for FMD and PWV were calculated by using a random-effect model. The presence of heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by the I2 statistic.

Results

A total of 26 eligible studies (n = 668 patients) were included in the present meta-analysis. Among newer antidiabetic drugs, only SGLT-2 inhibitors significantly improved FMD (pooled MD 1.14%, 95% CI: 0.18 to 1.73, p = 0.016), but not DPP-4 inhibitors (pooled MD = 0.86%, 95% CI: -0.15 to 1.86, p = 0.095) or GLP-1 RA (pooled MD = 2.37%, 95% CI: -0.51 to 5.25, p = 0.107). Both GLP-1 RA (pooled MD = −1.97, 95% CI: -2.65 to -1.30, p < 0.001) and, to a lesser extent, DPP-4 inhibitors (pooled MD = -0.18, 95% CI: -0.30 to -0.07, p = 0.002) significantly decreased PWV.

Conclusions

Newer antidiabetic drugs differentially affect endothelial function and arterial stiffness, as assessed by FMD and PWV, respectively. These findings could explain the distinct effects of these drugs on cardiovascular risk of patients with type 2 diabetes.

1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic disease affecting 8.3% of the adult population worldwide, with a rising prevalence that renders its tackling a global challenge [1]. Patients with T2D are at high cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [2, 3] and are characterized by micro- and macrovascular dysfunction which is of multifactorial origin [4, 5].

The safety and effects of newly licensed antidiabetic drugs on the cardiovascular system represent important clinical issues [6, 7]. Recent evidence from clinical trials suggests that newer antidiabetic drugs can not only exert glycemic-lowering properties but also decrease CVD risk [8, 9]. In this context, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, i.e., empagliflozin in the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients-Removing Excess Glucose (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) study [8] and canagliflozin in the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study [10], significantly reduced the rates of CVD events, hospitalization for heart failure (HF), CVD, and total mortality, as well as improved kidney function in T2D patients with established CVD. Similar beneficial effects were reported for liraglutide, an once-daily glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA), and for semaglutide, an once-weekly GLP-1 RA, both of which reduced CVD morbidity and mortality (but not hospitalization for HF) in T2D patients with established CVD, in the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial [9] and the Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes with Semaglutide in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes (SUSTAIN-6) [11], respectively. In contrast, lixisenatide once daily and exenatide once weekly did not affect CVD risk in the Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) trial [12] and the Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering (EXSCEL) [13], respectively. Furthermore, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors seem to exert neutral effects on CVD risk as shown for alogliptin in the Examination of Cardiovascular Outcomes with Alogliptin versus Standard of Care (EXAMINE) trial [14] and for sitagliptin in the Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin (TECOS) [15]. Saxagliptin was reported to increase the rate of hospitalization for HF [16] in the Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (SAVOR)–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 53 trial. Despite this evidence provided by large randomized clinical trials, the mechanisms by which antidiabetic drugs can affect CVD risk remain not entirely clear.

Vascular dysfunction is one of the initial steps in the atherosclerotic process [17, 18]. Endothelial function and arterial stiffness [17, 19] are two widely used indices of vascular function, which both offer prognostic information on the risk of CVD events in T2D patients [19]. Improvement of these indices represents one of the mechanisms by which drugs with established CVD benefits, such as statins, exert their effects [20, 21]. Currently, it remains unknown how newer antidiabetic drugs may affect vascular function as studies have yielded conflicting results.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature, followed by a meta-analysis, to investigate the effects of newer antidiabetic drugs, i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 RAs, and SGLT-2 inhibitors, on vascular function as assessed by flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery and pulse wave velocity (PWV).

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

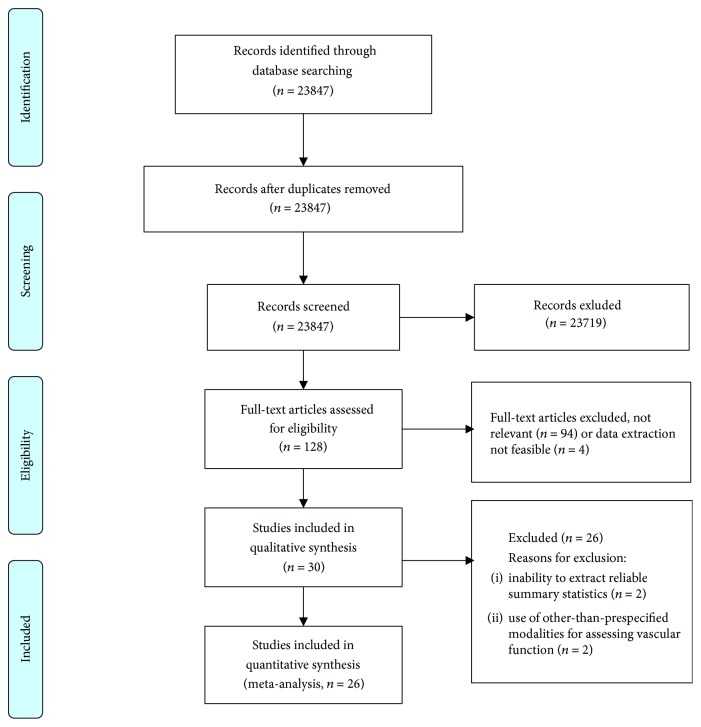

Eligible studies evaluating the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 RAs, and SGLT-2 inhibitors on FMD and PWV were drawn from a systematic review of the English literature in the MEDLINE and Web of Science databases up to 31 January 2018. The medical terms (MeSH) used were the following: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 OR SGLT2 OR empagliflozin OR canagliflozin OR dapagliflozin OR DPP-4 OR dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors OR sitagliptin OR saxagliptin OR vildagliptin OR linagliptin OR gemigliptin OR canagliptin OR teneligliptin OR alogliptin OR trelagliptin OR omarigliptin OR evogliptin OR dutogliptin OR GLP-1 OR glucagon-like peptide-1 OR exenatide OR lixisenatide OR dulaglutide OR liraglutide OR semaglutide AND endothelial function OR arterial stiffness OR flow-mediated dilation OR pulse wave velocity. Studies were also identified from searching the references of published articles. The PRISMA flow chart for the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

2.2. Study Eligibility

Studies were eligible if they were full-length publications in peer-reviewed journals reporting on (a) endothelium-dependent vasodilatory response by FMD and/or (b) arterial stiffness assessed by carotid-femoral, carotid-radial, or brachial-ankle PWV. Studies need also to be either double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials or observational studies assessing the outcomes of interest before and after treatment with a newer antidiabetic drug. No restriction criteria were imposed with regard to the size of the population studied. Analysis did not include studies assessing endothelial function or arterial stiffness by other markers. Only human studies were included in the analysis, whereas review articles were excluded.

2.3. Extraction of Data

Literature search, selection of studies, and extraction of data were performed independently by two investigators (KB and AA). Means and standard deviations (SD) of FMD and PWV as well as their changes following drug treatment were recorded from cumulative published data. In studies reporting standard error, SD was calculated using the equation SD = standard error∗√n. In studies reporting median and interquartile range, mean and SD were calculated and used in further analyses [22]. In those studies where extraction of cumulative statistics could not be reliably performed based on the full-length publication, a communication with the corresponding author was attempted to provide summary statistics [23–27].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For each eligible study, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for endothelium-dependent vasodilation and arterial stiffness as summary statistics (MD pre- and posttreatment). The difference in mean ± SD for FMD and PWV was included in the quantitative synthesis to explore the pooled MD after treatment with any of the studied antidiabetic drugs; the results were presented in respective forest plots. Subgroup analysis was performed for different drug classes. The presence of heterogeneity was evaluated by the I2 statistic. A random-effect model was used to obtain pooled MD and 95% CIs. Results were considered statistically significant at two-tailed p value < 0.05. The findings of the meta-analysis were also confirmed in leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. The quality of published studies was assessed by the modified version of the Downs and Black questionnaire [28]. The effect of publication bias on pooled estimates was explored by the Duval and Tweedie nonparametric “trim and fill” method and the construction of relevant funnel plots. All statistical analyses were performed by STATA software version 13.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, US).

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Summary

The literature search identified 30 studies for potential inclusion in the present meta-analysis. Certain identified studies that were originally included in the qualitative synthesis had to be excluded from the quantitative synthesis due to not fulfilling the eligibility criteria. One study was excluded because it assessed endothelial function by reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry [29] and one because it used a 24 h approach to measure PWV [30]. Also, two studies had to be excluded due to inability to extract reliable summary statistics for the outcomes of interest [26, 27] (Figure 1). Therefore, a total of 26 studies (n = 668 patients) were finally included in the quantitative synthesis. The details of the individual studies included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of studies included in the analysis.

| Author | Class | Agent | Study design | N | Duration | FMD (%) | PWV (m/s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (days) | Baseline | Post | Baseline | Post | |||||

| Ayaori et al. [31] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin | RCT | 42 | 42 | 7.2 ± 5.9 | 4.4 ± 5.9 | ||

| Alogliptin | 6.9 ± 6.3 | 4.4 ± 6.2 | |||||||

| Baltzis et al. [32] | DPP-4i | Linagliptin | RCT | 19 | 84 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | ||

| de Boer et al. [33] | DPP-4i | Linagliptin | RCT | 22 | 182 | 8.7 ± 1.6 | 8.3 ± 1.3 | ||

| Dell'Oro et al. [34] | DPP-4i | Saxagliptin | RCT | 16 | 360 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | ||

| Duvnjak et al. [49] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin/vildagliptin | Open label (NR) | 51 | 90 | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | ||

| Gurkan et al. [35] | GLP-1 RA | Exenatide | RCT | 17 | 182 | 6.4 ± 5.7 | 8.6 ± 4.7 | ||

| Hong et al. [50] | GLP-1 RA | Exenatide | Single arm (NR) | 32 | 90 | 7.2 ± 2.2 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | ||

| Hopkins et al. [51] | GLP-1 RA | Exenatide/liraglutide | Single arm (NR) | 11 | 180 | 6.2 ± 2.3 | 5.1 ± 2.7 | ||

| Ida et al. [52] | DPP-4i | Trelagliptin | Single arm (NR) | 27 | 84 | 2.4 ± 2.7 | 2.7 ± 3.8 | 16.3 ± 2.4 | 15.6 ± 2.2∗ |

| Irace et al. [36] | GLP-1 RA | Exenatide | RCT | 10 | 112 | 1.6 ± 2.9 | 9.1 ± 3.6 | ||

| Nakamura et al. [24] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin | RCT | 24 | 90 | 5.4 ± 2.3 | 6.2 ± 2.0 | ||

| Kim et al. [37] | DPP-4i | Vildagliptin | RCT | 17 | 84 | 9.4 ± 5.0 | 7.9 ± 4.3 | ||

| Kitao et al. [38] | DPP-4i | Vildagliptin | RCT | 48 | 84 | 5.5 ± 2.0 | 5.1 ± 2.3 | ||

| Kubota et al. [53] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin | Single arm (NR) | 40 | 90 | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 5.1 ± 1.6 | ||

| Lambadiari et al. [39] | GLP-1 RA | Liraglutide | RCT | 30 | 180 | 8.9 ± 3.0 | 13.2 ± 6.0 | 11.8 ± 2.5 | 10.3 ± 3.3 |

| Leung et al. [40] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin/vildagliptin | RCT | 25 | 365 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 7.3 ± 1.6 | ||

| Li et al. [41] | DPP-4i | Saxagliptin | RCT | 14 | 84 | 9.3 ± 4.7 | 14.3 ± 4.3 | ||

| Nomoto et al. [42] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin | RCT | 48 | 182 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | ||

| Nomoto et al. [43] | GLP-1 RA | Liraglutide | RCT | 16 | 98 | 6.0 ± 2.6 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | ||

| Shigiyama et al. [44] | SGLT-2i | Dapagliflozin | RCT | 37 | 112 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | ||

| Shigiyama et al. [45] | DPP-4i | Linagliptin | RCT | 29 | 112 | 4.9 ± 2.7 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | ||

| Solini et al. [46] | SGLT-2i | Dapagliflozin | RCT | 16 | 2 | 2.8 ± 2.3 | 4.0 ± 2.1 | 10.1 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 1.6 |

| Suzuki et al. [25] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin | RCT | 12 | 90 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 5.4 ± 2.2 | ||

| Maruhashi et al. [23] | DPP-4i | Sitagliptin | RCT | 17 | 720 | 4.3 ± 2.6 | 4.4 ± 2.3 | ||

| Widlansky et al. [47] | DPP-4i | Saxagliptin | RCT | 16 | 56 | 5.6 ± 2.3 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | ||

| Zografou et al. [48] | DPP-4i | Vildagliptin | RCT | 32 | 180 | 8.6 ± 2.1 | 8.3 ± 1.5 | ||

DPP-4i: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; FMD: flow-mediated dilation; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; NR: nonrandomized; RCT: randomized clinical trial; SGLT-2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor; PWV: pulse wave velocity. N refers to the active treatment group. The full list of references of the studies included in the table is provided in the supplementary material. ∗Measured as brachial-ankle PWV.

All studies were published since 2012. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 10 to 51 patients. The mean follow-up time was 152 days after initiation of treatment. The majority of studies were randomized controlled trials [23–25, 31–48], but some of them were uncontrolled or single-arm observational studies [49–53]. All studies performed the ultrasound-based technique to assess brachial artery FMD and PWV to assess arterial stiffness.

3.2. Quantitative Synthesis

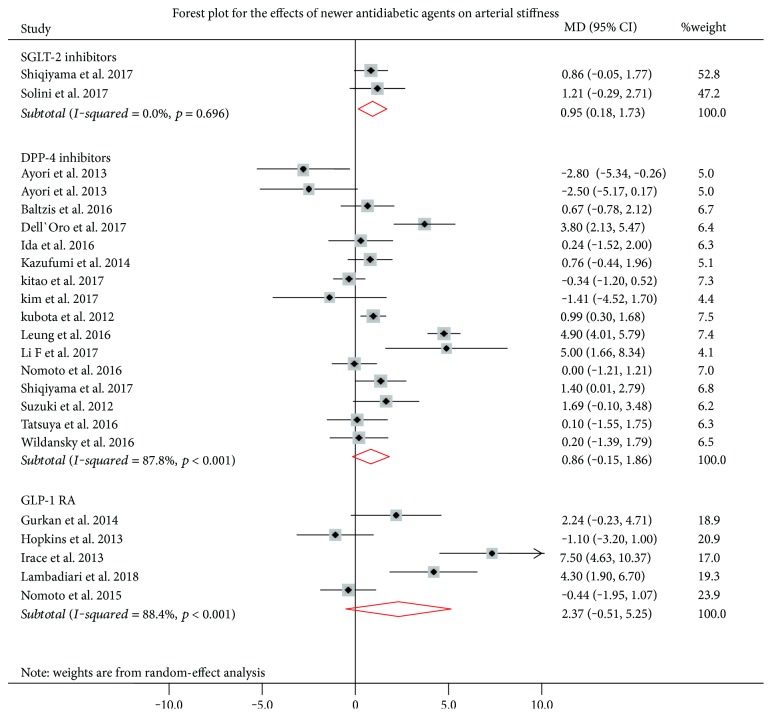

3.2.1. Effects of Newer Antidiabetic Drugs on Endothelial Function

The effects of newer antidiabetic drugs on FMD are summarized in Figure 2. Overall, 16 studies investigated the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on FMD. In the pooled meta-analysis, the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on FMD was not statistically significant (pooled MD = 0.86%, 95% CI: -0.15 to 1.86, p = 0.095). But there was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 87.8%, p < 0.0001). In leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, the results were unchanged (Table 2); only by excluding the study of Ayaori et al. [31] was a significant effect of DPP-4 on FMD observed (pooled MD = 1.25%, 95% CI: 0.24 to 2.27, p = 0.015), but heterogeneity among studies remained significant. Even within the group of DPP-4 inhibitors, no specific agent was associated with significant improvements in FMD.

Figure 2.

Effects of newer antidiabetic drugs on endothelial function. Squares indicate the mean difference (MD) and the respective 95% confidence intervals in flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) before/after treatment from eligible studies. The size of the squares corresponds to the weight of each study. The diamonds and their width represent the pooled MD and the 95% CI, respectively. DPP-4 = DPP-4 inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors, and GLP-1 RAs and defines them under the figure. DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1 RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; SGLT-2: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2.

Table 2.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effects of newer antidiabetics on endothelial function.

| Study excluded | MD (95% CI) | p value | Heterogeneity (I2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 inhibitors | |||

| Ayaori et al. [31] | 1.253 (0.242 to 2.265) | p = 0.015 | 87.7%, p < 0.001 |

| Baltzis et al. [32] | 0.866 (-0.205 to 1.936) | p = 0.113 | 88.6%, p < 0.001 |

| Dell'Oro et al. [34] | 0.658 (-0.365 to 1.682) | p = 0.207 | 87.8%, p < 0.001 |

| Ida et al. [52] | 0.897 (-0.151 to 1.945) | p = 0.095 | 88.5%, p < 0.001 |

| Nakamura et al. [24] | 0.858 (-0.226 to 1.943) | p = 0.121 | 88.6%, p < 0.001 |

| Kim et al. [37] | 0.962 (-0.066 to 1.990) | p = 0.067 | 88.3%, p < 0.001 |

| Kitao et al. [38] | 0.948 (-0.115 to 2.011) | p = 0.080 | 87.1%, p < 0.001 |

| Kubota et al. [53] | 0.832 (-0.329 to 1.993) | p = 0.160 | 88.6%, p < 0.001 |

| Leung et al. [40] | 0.566 (-0.130 to 1.261) | p = 0.111 | 68.6%, p < 0.001 |

| Li et al. [41] | 0.679 (-0.337 to 1.695) | p = 0.190 | 88.1%, p < 0.001 |

| Nomoto et al. [42] | 0.917 (-0.153 to 1.986) | p = 0.093 | 88.2%, p < 0.001 |

| Shigiyama et al. [44] | 0.813 (-0.262 to 1.888) | p = 0.138 | 88.6%, p < 0.001 |

| Suzuki et al. [25] | 0.798 (-0.261 to 1.858) | p = 0.140 | 88.6%, p < 0.001 |

| Maruhashi et al. [23] | 0.906 (-0.152 to 1.964) | p = 0.093 | 88.4%, p < 0.001 |

| Widlansky et al. [47] | 0.899 (-0.161 to 1.960) | p = 0.097 | 88.5%, p < 0.001 |

| GLP-1 RA | |||

| Gurkan et al. [35] | 2.435 (-1.177 to 6.047) | p = 0.186 | 91.2%, p < 0.001 |

| Hopkins et al. [51] | 3.275 (-0.132 to 6.682) | p = 0.060 | 89.2%, p < 0.001 |

| Irace et al. [36] | 1.141 (-1.194 to 3.476) | p = 0.338 | 80.2%, p = 0.001 |

| Lambadiari et al. [39] | 1.902 (-1.399 to 5.203) | p = 0.259 | 89.3%, p < 0.001 |

| Nomoto et al. [42] | 3.155 (-0.376 to 6.687) | p = 0.080 | 88.1%, p < 0.001 |

DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

For the effect of GLP-1 RAs (liraglutide and exenatide) on FMD (5 studies; n = 84 patients), the pooled estimate effect was not significant (pooled MD = 2.38%, 95% CI: -0.51 to 5.25, p = 0.107). Heterogeneity among studies was significant (I2 = 88.4%, p < 0.001). In leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, the results were unchanged and the heterogeneity among studies remained significant.

Only 2 eligible studies (n = 53 patients) evaluated the effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors on FMD. Dapagliflozin was the only SGLT-2 inhibitor used in these studies. SGLT-2 inhibitors increased FMD significantly (pooled MD = 0.95%, 95% CI: 0.18 to 1.73, p = 0.016).

In metaregression analysis, the mean difference in FMD was not associated with the size of the study (b = −0.033, p = 0.489), the duration of intervention (b = 0.002, p = 0.460), the age (b = −0.162, p = 0.163) or the sex (for males: b = 0.004, p = 0.931) of participants enrolled.

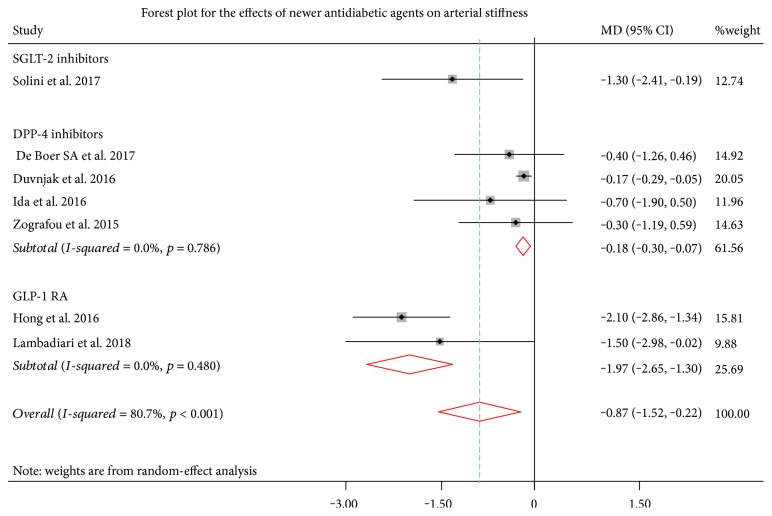

3.2.2. Effects of Newer Antidiabetic Drugs on Arterial Stiffness

The effects of newer antidiabetic drugs on PWV are summarized in Figure 3. Marked heterogeneity was observed among analyzed studies (I2 = 80.7%, p < 0.001). A total of 4 studies (n = 132 patients) investigated the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on arterial stiffness, which were associated with a significant reduction in PWV (pooled MD = −0.18, 95% CI: -0.30 to -0.07, p = 0.002). A similar effect was identified for GLP-1 RAs (2 studies; n = 62 patients), which were associated with a significant reduction in PWV (pooled MD = −1.97, 95% CI: -2.65 to -1.30, p < 0.001). For SGLT-2 inhibitors, only one study reported a reduction in PWV, and therefore, no safe conclusions can be drawn.

Figure 3.

Effects of newer antidiabetic drugs on arterial stiffness. Squares indicate the mean difference (MD) and the respective 95% confidence intervals in pulse wave velocity (PWV) before/after treatment from eligible studies. The size of the squares corresponds to the weight of each study. The diamonds and their width represent the pooled weighted MD and the 95% CI, respectively. DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1 RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; SGLT-2: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2.

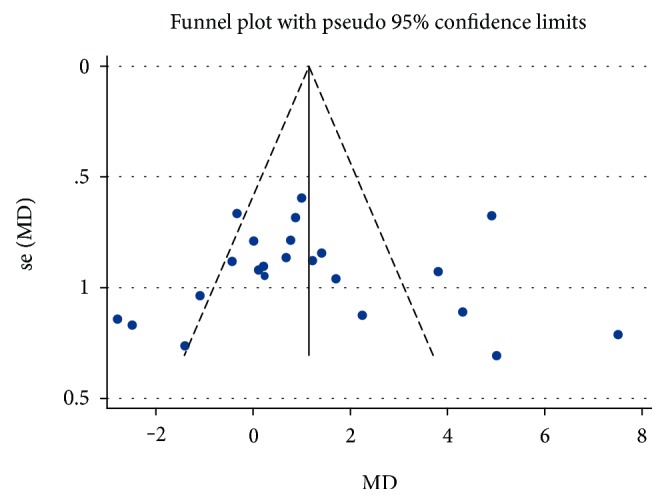

3.3. Quality Assessment of Included Studies and Publication Bias

The quality of published studies was assessed by the modified Downs and Black checklist [28]. The quality of published studies is considered moderate with a mean modified Downs and Black score of 23.1. To explore publication bias, we constructed a funnel plot of published studies for the effect size of antidiabetic drugs on the primary endpoint of our study, i.e., endothelial function assessed by FMD. The funnel plot was symmetric, suggesting the absence of publication bias (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot and assessment of publication bias. Funnel plot with 95% pseudoconfidence intervals of the effect size and its standard error for studies assessing the effects of newer antidiabetic drugs on the primary endpoint endothelial function. Large studies appear toward the top of the graph and tend to cluster near the mean effect size. Smaller studies appear toward the bottom of the graph and (since there is more sampling variation in effect size estimates in the smaller studies) will be dispersed across a range of values. The symmetric distribution of studies about the combined effect size indicates the absence of publication bias.

4. Discussion

In the present systematic review, we sought to explore the effects of newer antidiabetic drugs, namely, SGLT-2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, and GLP-1 RAs, on vascular function. We hypothesized that the distinct profile of each antidiabetic drug class could be also associated with differences in their vascular effects. The systematic review of the published literature showed that evidence in this field is modest, based mainly on small randomized clinical trials with significant heterogeneity. In this context, published studies supported a beneficial effect of SGLT-2 on FMD, which seems to not be shared by GLP-1 RAs or DPP-4 inhibitors. Accordingly, evidence suggested a reduction in PWV by both DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs. These findings are potentially important as they suggest a different impact of newer antidiabetic drugs on vascular function, which could be linked with their distinct effects on CVD risk. However, these results should be interpreted with caution given the modest quality of evidence in the published literature and the significant heterogeneity between studies.

DPP-4 inhibitors are an antidiabetic drug class on which there is abundant clinical experience, since they have been marketed for over a decade (since 2006). Large randomized clinical trials in the field are consistent in their findings and support a neutral effect of DPP-4 inhibitors on CVD outcomes. However, there is evidence that saxagliptin may increase the risk for HF hospitalization [16]. Recent meta-analyses have also found that DPP-4 inhibitors do not affect the risk for CVD mortality and stroke [54]. Data from the small clinical studies included in the present meta-analysis indicate a marginal effect of DPP-4 drugs on FMD and a significant reduction in PWV. These small effects could be related to the glucose-lowering properties of DPP-4 inhibition but may not be commonly shared by all agents of the DPP-4 drug class. This is an interest finding which (a) confirms the safety profile of this drug class and (b) may explain the neutral effect of certain DPP-4 drugs on CVD outcomes.

For SGLT-2 inhibitors, evidence suggests a beneficial effect of these agents on CVD risk and mortality in T2D patients with established CVD. Evidence from randomized clinical trials suggests that empagliflozin and canagliflozin significantly reduce the CVD morbidity, all-cause mortality, and CVD mortality as well as HF hospitalization and nephropathy development or progression [8]. Similar effects have also been reported for canagliflozin [10]. These benefits could be related to glucose-lowering as well as to reductions in blood pressure, weight, and serum uric acid and to improvements in oxidative stress, glomerular hyperfiltration, albuminuria, arterial stiffness, plasma lipids, sympathetic nervous system activity, myocardial oxygen consumption, and cardiac workload [55]. Our findings complement these SGLT-2 inhibitor actions, suggesting also a significant improvement in FMD. Concerning the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on arterial wave velocity, it should be noted that despite the ample evidence on the impact of this class of drugs on natriuresis and blood pressure [8, 10], more data are required to assess the effects of these drugs on PWV, as there are only few published data on this topic [46].

Our findings also agree with the published evidence from large randomized clinical trials on the effects of liraglutide [9] and semaglutide [11] on CVD outcomes in T2D patients. In the present meta-analysis, GLP-1 RAs significantly decreased PWV in T2D patients, although they did not affect FMD. Since the effects of these drugs on CVD risk is still debatable [12, 56], it remains to be seen whether their impact on vascular function may play a role in determining their CVD effects.

The limitations of the existing studies in the field should be noted. The published evidence is modest and mainly based on small-sized randomized clinical studies, some of which were uncontrolled. Furthermore, studies were significantly heterogeneous, and therefore, the results of the present meta-analysis should be interpreted cautiously. The number of the published studies in this field did not allow for subgroup analysis per drug class or for between-agent comparisons within the same drug class. Furthermore, based on the published literature, we cannot conclude whether beneficial effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors, DDP-4 inhibitors, and GLP-1 RAs are due to direct glucose-lowering effects or to indirect effects driven by the modulation of other cardiovascular risk factors such as body weight loss and arterial blood pressure modification [8–11, 57]. More data is also warranted for the effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on arterial stiffness as well as endothelial function as there are limited published studies reporting on their effects.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis suggests that the published literature in the field of newer antidiabetic drugs and vascular function is of modest quality and characterized by significant heterogeneity among studies. Overall, both DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs were shown to significantly decrease PWV without affecting FMD. In contrast, SGLT-2 inhibitors significantly improved FMD, but concrete data on their effects on PWV is still missing. Whether these distinct properties of newer antidiabetic drugs, in relation to their effects on endothelial function and arterial stiffness, may explain their differential effects on CVD risk remains to be elucidated in future studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shaw J. E., Sicree R. A., Zimmet P. Z. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2010;87(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. The Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2215–2222. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Low Wang C. C., Hess C. N., Hiatt W. R., Goldfine A. B. Clinical update: cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus – mechanisms, management and clinical considerations. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2459–2502. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.022194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonopoulos A. S., Siasos G., Tousoulis D. Microangiopathy, arterial stiffness, and risk stratification in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Cardiology. 2017;2(7):820–821. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonopoulos A. S., Margaritis M., Coutinho P., et al. Adiponectin as a link between type 2 diabetes and vascular NADPH oxidase activity in the human arterial wall: the regulatory role of perivascular adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2015;64(6):2207–2219. doi: 10.2337/db14-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nissen S. E., Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(24):2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holman R. R., Sourij H., Califf R. M. Cardiovascular outcome trials of glucose-lowering drugs or strategies in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383(9933):2008–2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60794-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinman B., Wanner C., Lachin J. M., et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(22):2117–2128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marso S. P., Daniels G. H., Brown-Frandsen K., et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(4):311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neal B., Perkovic V., Mahaffey K. W., et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(7):644–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marso S. P., Bain S. C., Consoli A., et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(19):1834–1844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeffer M. A., Claggett B., Diaz R., et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(23):2247–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holman R. R., Bethel M. A., Mentz R. J., et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(13):1228–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White W. B., Cannon C. P., Heller S. R., et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(14):1327–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green J. B., Bethel M. A., Armstrong P. W., et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(3):232–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scirica B. M., Bhatt D. L., Braunwald E., et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(14):1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonopoulos A. S., Sanna F., Sabharwal N., et al. Detecting human coronary inflammation by imaging perivascular fat. Science Translational Medicine. 2017;9(398, article eaal2658) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonopoulos A. S., Tousoulis D. The molecular mechanisms of obesity paradox. Cardiovascular Research. 2017;113(9):1074–1086. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonopoulos A. S., Siasos G., Konsola T., et al. Arterial wall elastic properties and endothelial dysfunction in the diabetic foot syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(11):e180–e181. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoniades C., Bakogiannis C., Leeson P., et al. Rapid, direct effects of statin treatment on arterial redox state and nitric oxide bioavailability in human atherosclerosis via tetrahydrobiopterin-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling. Circulation. 2011;124(3):335–345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniades C., Bakogiannis C., Tousoulis D., et al. Preoperative atorvastatin treatment in CABG patients rapidly improves vein graft redox state by inhibition of Rac1 and NADPH-oxidase activity. Circulation. 2010;122(11) Supplement 1:S66–S73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hozo S. P., Djulbegovic B., Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2005;5(1):p. 13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.for the PROLOGUE Study Investigators, Maruhashi T., Higashi Y., et al. Long-term effect of sitagliptin on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes: a sub-analysis of the PROLOGUE study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2016;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0438-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura K., Oe H., Kihara H., et al. DPP-4 inhibitor and alpha-glucosidase inhibitor equally improve endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes: EDGE study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2014;13(1):p. 110. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0110-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K., Watanabe K., Suzuki T., et al. Sitagliptin improves vascular endothelial function in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease. Journal of Diabetes Mellitus. 2012;2(3):338–345. doi: 10.4236/jdm.2012.23053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jax T., Stirban A., Terjung A., et al. A randomised, active- and placebo-controlled, three-period crossover trial to investigate short-term effects of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin on macro- and microvascular endothelial function in type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2017;16(1):p. 13. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0493-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X. H., Han L. N., Yu Y. R., et al. Effects of GLP-1 agonist exenatide on cardiac diastolic function and vascular endothelial function in diabetic patients. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao. Yi Xue Ban. 2015;46(4):586–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downs S. H., Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsubara J., Sugiyama S., Akiyama E., et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, improves endothelial dysfunction in association with its anti-inflammatory effects in patients with coronary artery disease and uncontrolled diabetes. Circulation Journal. 2013;77(5):1337–1344. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Striepe K., Jumar A., Ott C., et al. Effects of the selective sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin on vascular function and central hemodynamics in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2017;136(12):1167–1169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayaori M., Iwakami N., Uto-Kondo H., et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors attenuate endothelial function as evaluated by flow-mediated vasodilatation in type 2 diabetic patients. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2(1, article e003277) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baltzis D., Dushay J. R., Loader J., et al. Effect of linagliptin on vascular function: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;101(11):4205–4213. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Boer S. A., Heerspink H. J. L., Juárez Orozco L. E., et al. Effect of linagliptin on pulse wave velocity in early type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, controlled 26-week trial (RELEASE) Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2017;19(8):1147–1154. doi: 10.1111/dom.12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dell’Oro R., Maloberti A., Nicoli F., et al. Long-term saxagliptin treatment improves endothelial function but not pulse wave velocity and intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients. High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention. 2017;24(4):393–400. doi: 10.1007/s40292-017-0215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurkan E., Tarkun I., Sahin T., Cetinarslan B., Canturk Z. Evaluation of exenatide versus insulin glargine for the impact on endothelial functions and cardiovascular risk markers. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2014;106(3):567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irace C., de Luca S., Shehaj E., et al. Exenatide improves endothelial function assessed by flow mediated dilation technique in subjects with type 2 diabetes: results from an observational research. Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research. 2012;10(1):72–77. doi: 10.1177/1479164112449562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim G., Oh S., Jin S. M., Hur K. Y., Kim J. H., Lee M. K. The efficacy and safety of adding either vildagliptin or glimepiride to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2017;18(12):1179–1186. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1353080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitao N., Miyoshi H., Furumoto T., et al. The effects of vildagliptin compared with metformin on vascular endothelial function and metabolic parameters: a randomized, controlled trial (Sapporo Athero-Incretin Study 3) Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2017;16(1):p. 125. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0607-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambadiari V., Pavlidis G., Kousathana F., et al. Effects of 6-month treatment with the glucagon like peptide-1 analogue liraglutide on arterial stiffness, left ventricular myocardial deformation and oxidative stress in subjects with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2018;17(1):p. 8. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0646-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung M., Leung D. Y., Wong V. W. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors on cardiac and endothelial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research. 2016;13(3):236–243. doi: 10.1177/1479164116629352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li F., Chen J., Leng F., Lu Z., Ling Y. Effect of saxagliptin on circulating endothelial progenitor cells and endothelial function in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 2017;125(6):400–407. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-124421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nomoto H., Miyoshi H., Furumoto T., et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of sitagliptin and glimepiride on endothelial function and metabolic parameters: Sapporo Athero-Incretin Study 1 (SAIS1) PLoS One. 2016;11(10):p. e0164255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nomoto H., Miyoshi H., Furumoto T., et al. A comparison of the effects of the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide and insulin glargine on endothelial function and metabolic parameters: a randomized, controlled trial Sapporo Athero-Incretin Study 2 (SAIS2) PLoS One. 2015;10(8):p. e0135854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shigiyama F., Kumashiro N., Miyagi M., et al. Effectiveness of dapagliflozin on vascular endothelial function and glycemic control in patients with early-stage type 2 diabetes mellitus: DEFENCE study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2017;16(1):p. 84. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0564-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shigiyama F., Kumashiro N., Miyagi M., et al. Linagliptin improves endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized study of linagliptin effectiveness on endothelial function. Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2017;8(3):330–340. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solini A., Giannini L., Seghieri M., et al. Dapagliflozin acutely improves endothelial dysfunction, reduces aortic stiffness and renal resistive index in type 2 diabetic patients: a pilot study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2017;16(1):p. 138. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0621-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Widlansky M. E., Puppala V. K., Suboc T. M., et al. Impact of DPP-4 inhibition on acute and chronic endothelial function in humans with type 2 diabetes on background metformin therapy. Vascular Medicine. 2017;22(3):189–196. doi: 10.1177/1358863X16681486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zografou I., Sampanis C., Gkaliagkousi E., et al. Effect of vildagliptin on hsCRP and arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hormones. 2015;14(1):118–125. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duvnjak L., Blaslov K. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors improve arterial stiffness, blood pressure, lipid profile and inflammation parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetology and Metabolic Syndrome. 2016;8(1):p. 26. doi: 10.1186/s13098-016-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong J. Y., Park K. Y., Kim B. J., Hwang W. M., Kim D. H., Lim D. M. Effects of short-term exenatide treatment on regional fat distribution, glycated hemoglobin levels, and aortic pulse wave velocity of obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;31(1):80–85. doi: 10.3803/enm.2016.31.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hopkins N. D., Cuthbertson D. J., Kemp G. J., et al. Effects of 6 months glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 2013;15(8):770–773. doi: 10.1111/dom.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ida S., Murata K., Betou K., et al. Effect of trelagliptin on vascular endothelial functions and serum adiponectin level in patients with type 2 diabetes: a preliminary single-arm prospective pilot study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2016;15(1):p. 153. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0468-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kubota Y., Miyamoto M., Takagi G., et al. The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin improves vascular endothelial function in type 2 diabetes. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2012;27(11):1364–1370. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.11.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Savarese G., D'Amore C., Federici M., et al. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and sodium-glucose linked cotransporter-2 inhibitors on cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;220:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katsiki N., Mikhailidis D. P., Theodorakis M. J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i): their role in cardiometabolic risk management. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2017;23(10):1522–1532. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170113152742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Margulies K. B., Anstrom K. J., Hernandez A. F., et al. GLP-1 agonist therapy for advanced heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: design and rationale for the functional impact of GLP-1 for heart failure treatment study. Circulation. Heart Failure. 2014;7(4):673–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.000346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang X., Zhao Q. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors on blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hypertension. 2016;34(2):167–175. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]