ABA produced in the fig fruit triggers ethylene production in the inflorescence and induces non-climacteric ripening in the receptacle tissue.

Keywords: Abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene, FcACS4, FcNCED2, Ficus carica, fruit ripening, on-tree treatment

Abstract

The common fig bears a unique closed inflorescence structure, the syconium, composed of small individual drupelets that develop from the ovaries, which are enclosed in a succulent receptacle of vegetative origin. The fig ripening process is traditionally classified as climacteric; however, recent studies have suggested that distinct mechanisms exist in its reproductive and non-reproductive parts. We analysed ABA and ethylene production, and expression of ABA-metabolism, ethylene-biosynthesis, MADS-box, NAC, and ethylene response-factor genes in inflorescences and receptacles of on-tree fruit treated with ABA, ethephon, fluridone, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA). Exogenous ABA and ethephon accelerated fruit ripening and softening, whereas fluridone and NDGA had the opposite effect, delaying endogenous ABA and ethylene production compared to controls. Expression of the ABA-biosynthesis genes FcNCED2 and FcABA2, ethylene-biosynthesis genes FcACS4, FcACOL, and FcACO2, FcMADS8, 14, 15, FcNAC1, 2, 5, and FcERF9006 was up-regulated by exogenous ABA and ethephon. NDGA down-regulated FcNCED2 and FcABA2, whereas fluridone down-regulated FcABA2; both down-regulated the ethylene-related genes. These results demonstrate the key role of ABA in regulation of ripening by promoting ethylene production, as in the climacteric model plant tomato, especially in the inflorescence. However, increasing accumulation of endogenous ABA until full ripeness and significantly low expression of ethylene-biosynthesis genes in the receptacle suggests non-climacteric, ABA-dependent ripening in the vegetative-originated succulent receptacle part of the fruit.

Introduction

Fruit ripening involves the well-orchestrated coordination of several regulatory steps in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruit, together with strong metabolic and physiological changes (Kumar et al., 2014). Fig fruit (Ficus carica) are categorized as climacteric; they show a rise in respiration rate and ethylene production at the onset of their ripening phase (Marei and Crane, 1971; Chessa et al., 1992), similar to that of the climacteric tomato, apple, and mango fruit (Giovannoni, 2001; Adams-Phillips et al., 2004; Zaharah et al., 2012). However, unlike climacteric fruit, figs harvested before they are fully ripe never complete their ripening process to reach commercially desirable parameters of size, color, flavor, and texture (Flaishman et al., 2008). This challenges the idea that fig fruit are climacteric. In addition,1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP), which blocks the effects of ethylene during ripening, increases ripening-related ethylene production in fig fruit following pre- or post-harvest application in an unexpected auto-inhibitory manner (Sozzi et al., 2005; Owino et al., 2006; Freiman et al., 2012). A molecular study of ethylene-related genes in figs (Freiman et al., 2015) showed that FcERF12185, an ethylene signal-transduction gene, might be responsible for the non-climacteric auto-inhibition of ethylene production in the fruit. Unlike most fig ethylene-response factor (ERF) genes, FcERF12185 expression does not increase during ripening, and is induced upon 1-MCP treatment (Freiman et al., 2015).

It has been suggested that the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) regulates fruit ripening and senescence in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruit (Zhang et al., 2009a, 2009b; Sun et al., 2012; Leng et al., 2014). In climacteric fruit, endogenous ABA levels increase before the onset of ripening and subsequently decrease until the fruit is fully ripe. However, in non-climacteric fruit, ABA levels increase from maturation to harvest (Setha, 2012; Leng et al., 2014).

The fig fruit bears a unique closed inflorescence structure, the syconium. This closed inflorescence produces an aggregate fruit, which is composed of small individual drupelets that develop from the ovaries enclosed in the receptacle (Storey et al., 1977). Development of female fruit in the common fig consists of three phases: phase I is characterized by rapid growth in fruit size; in phase II, the fruit remains nearly the same size, color, and firmness; in phase III, ripening occurs, with fruit growth, color change, softening, and alteration of the pulp texture to an edible state (Flaishman et al., 2008). Endogenous ABA is reported to increase as the ripening phase progresses (Rosianski et al., 2016a). The endogenous ABA content in the fruit is determined by the dynamic balance between its biosynthesis and catabolism. Zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP), 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase (ABA2), and abscisic aldehyde oxidase participate in ABA biosynthesis, while ABA-8’-hydroxylase (ABA8OX) and ABA-glucosyltransferase participate in its catabolism (Schwartz et al., 2003; Setha et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2005; Jiang and Hartung, 2008; Seo and Koshiba, 2011; Leng et al., 2014; Rosianski et al., 2016a).

The effect of ABA on ethylene biosynthesis, fruit ripening, and senescence has been extensively studied in the model plant tomato. Exogenous ABA treatment increases ABA content in tomato fruit, and induces the expression of ethylene-biosynthesis genes, namely 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) synthase (ACS) and ACC oxidase (ACO). On the other hand, treatment of tomato fruit with the ABA inhibitors fluridone or nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) inhibits ACS and ACO and delays ripening and softening (Zhang et al., 2009b; Mou et al., 2016). In particular, a significant reduction in the activity of SlNCED1, a key gene in tomato ABA biosynthesis, by RNAi, reduces the expression of genes encoding major cell wall-catabolic enzymes, and increases the accumulation of pectin during ripening, which leads to a significant extension of the shelf-life of climacteric tomato fruit (Sun et al., 2012). Similarly, exogenous ABA application significantly promotes the ripening process of the non-climacteric strawberry fruit, whereas fluridone inhibits it. Down-regulation of the ABA-biosynthesis gene FaNCED1 in strawberry significantly decreases ABA levels and produces non-colored/unripe fruit (Jia et al., 2011). Moreover, studies in apple, banana, grape, and sweet cherry have shown that exogenous application of ABA enhances fruit ripening by up-regulating ethylene production, as well as anthocyanin and sugar accumulation (Jiang et al., 2000; Lara and Vendrell, 2000; Ban et al., 2003; Jiang and Joyce, 2003; Giribaldi et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2014). In fig fruit, genes of the ABA biosynthesis and catabolism pathways have been isolated and their expression characterized during ripening (Rosianski et al., 2016a).In addition, Freiman et al. (2015) performed a comprehensive study focusing on ethylene-biosynthesis, MADS-box, and ethylene signal-transduction genes during natural ripening and their interactions with 1-MCP. However, the relationship between ABA and ethylene during the onset of fruit ripening in fig remains to be fully elucidated.

The plant-specific NAC family of proteins containing the NAC domain is one of the largest transcription factor families in plants. An increasing number of NAC genes are being identified and studied in both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants . In tomato, 74 NAC or NAC-like genes belonging to 12 subfamilies have been identified, with high expression of SlNAC4–9 being found during fruit development and ripening (Kou et al., 2014). SlNAC1 has a broad influence on tomato fruit ripening, and its over-expression during ripening has been found to be regulated through both ethylene-dependent and ABA-dependent pathways (Ma et al., 2014). Reduced expression of SlNAC4 by RNAi in tomato results in delayed fruit ripening, with suppressed chlorophyll breakdown and decreased ethylene synthesis being mediated mainly through reduced expression of system-2 ethylene-biosynthesis genes, and with carotenoids being reduced via alteration of the flux of the carotenoid pathway (Zhu et al., 2014). In addition, SlNAC4 is down-regulated by ABA treatment while SlNAC5, 6, 7, and 9 are up-regulated (Kou et al., 2014). Involvement of NAC genes in banana fruit ripening was found via interactions with ethylene-signaling components (Shan et al., 2012). In figs, 27 NAC genes have been identified during fruit ripening (Freiman et al., 2014); however, their roles during this process are still unknown.

In the present work, we used exogenous ABA, ethephon, and the ABA inhibitors fluridone and NDGA to characterize the effects of ABA on fig fruit ripening. The expression levels of ABA- and ethylene-biosynthesis genes were determined, together with those of ripening-associated transcription factors and signal-transduction genes. The levels of endogenous ABA and ethylene were also quantified to determine how ABA triggers ethylene production to start the ripening process. This study also examined the genes that likely to be induced during on-tree fruit ripening. The non-climacteric ripening behavior of fig fruit associated with ABA is also discussed.

Materials and methods

Plant material and sample preparation

Fruit of common fig (Ficus carica L.) cv. Brown Turkey, 37 mm in diameter with a greenish-yellow ostiole color (just before the rapid increase in endogenous ABA production and the start of ethylene production), were selected for on-tree treatment with ABA, ethephon, fluridone, and NDGA in a fig orchard located at the Agricultural Research Organization – Volcani Center, Israel. Treatments were applied by injecting 1 ml of the following into the fruit through the ostiole with a plastic syringe: 1.89 mM ABA (Valent Bioscience Corporation, USA), 0.7 mM ethephon (Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha, Ltd., Japan), 0.15 mM NDGA, or 0.2 mM fluridone (both Sigma-Aldrich). ABA and ethephon were injected once at time 0, whilst NDGA and fluridone were injected three times at 12-h intervals starting at time 0. The size and ostiole color of the fruit used in the experiments and the treatment concentrations were selected on the basis of several preliminary trials (data not shown). Fruit treated with ddH2O served as the control group and ethephon-treated fruit served as a positive control.

Three separate experiments were performed: (i) ABA and ethephon treatment; (ii) fluridone treatment; and (iii) NDGA treatment. These trials were conducted during the summers of 2015 and 2016 (July–August), with average day and night temperatures of 32 °C and 24 °C, respectively. For fruit treated with ABA and ethephon, samples were collected at 0, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after treatment (HAT). Samples for the NDGA and fluridone treatments were collected at 0, 24, 32, 48, 72, and 96 HAT. In total, 600 fruit were treated in each experiment and physiological changes were examined. Nine fruit were harvested at each time interval for molecular characterization, divided into three biological replicates consisting of three fruit each. Fruit receptacle and inflorescence tissues were collected separately and stored at –80ºC until further analysis.

Fruit diameter and firmness

Fruit fresh weight was determined immediately on sampling. Width was measured using a standard caliber, and was recorded as the maximal horizontal diameter. Fruit firmness was measured using an Inspekt Table Blue universal testing machine with 5 kN capacity (Hegewald & Peschke MTP, Nossen, Germany), and expressed in Newtons as F(N), the energy used to deform the fruit to 5% of its diameter, as in Rosianski et al. (2016b).

Measurement of ethylene production

Ethylene production was determined according to Freiman et al. (2012) in a total of seven fruit at each sampling time. Individual fruit were enclosed in a 0.75-l airtight glass jar for 2 h at room temperature (20 °C)and ethylene was quantified using a Varian 3300 GC instrument with a flame-ionization detector (FID) (Varian Inc., CA, USA), a stainless-steel column (length 1.5 m, outside diameter 3.17 mm, internal diameter 2.16 mm) packed with HayeSep T, particle size 0.125–0.149 mm (Alltech Associates Inc., IL, USA), and helium as the carrier gas (5 ml min–1).

ABA extraction and quantification

Frozen receptacles or inflorescences were ground into powder and 0.5-g samples were dissolved in 3 ml of 80% acidified methanol and 1% acetic acid in 15-ml tubes. d4-ABA (7 µl of a 10× dilution) was added as an internal standard and, after vortexing, the mixture was stored at 4 °C for 2 h. Samples were centrifuged at 1510 g for 30 min at 4 °C and the upper phase was transferred to a new tube. The pellet was extracted again by adding 3 ml of 80% acidified methanol and storing overnight at 4 °C, before further centrifuging. The separated upper phases were combined and then evaporated at 40 °C down to 200 µl and stored at –20 °C for further analysis.

LC–MS analyses were conducted using a UPLC-Triple Quadrupole-MS (Waters Xevo TQ, MS, USA). Samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 13 362 g and 1 µl of supernatant was injected into the LC–MS instrument. Separation was performed on a 2.1 × 100 mm2, 1.7-µm ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column with a VanGuard pre-column (BEH C18 1.7 µm, 2.1 × 5 mm2). The chromatographic and MS parameters were as follows: the mobile phase consisted of water (phase A) and acetonitrile (phase B), both containing 0.1% formic acid, in gradient-elution mode. The solvent gradient program was as follows: 5% to 95% A over 0.1 min, 25% to 75% A over 2 min, 35% to 65% A over 2.5 min, 40% to 60% A over 3 min, held at 95% to 5% A for 4 min. At the end of the gradient, the column was washed with 95% B (3 min) and re-equilibrated to initial conditions for 3 min. The flow rate was 0.3 ml min–1, and the column temperature was kept at 35 °C. All of the analyses were performed using the ESI source in positive ion mode with the following settings: capillary voltage 3.5 kV, cone voltage 26 V, desolvation temperature 350 °C, desolvation gas flow 650 l h–1, source temperature 150 °C. Quantitation was performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) acquisition by monitoring 247/187, 247/173 (RT=3.93, dwell time of 78 ms for each transition) for ABA and 251/191, 251/177 (RT=3.93, dwell time of 78 ms) for d4-ABA (used as an internal standard). The LC–MS data were acquired using the MassLynx V4.1 software (Waters).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted according to Jaakola et al. (2001). The RNA concentration was determined in a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer, and its integrity was checked by running 1 μl in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel stained with Bromophenol Blue. Total RNA was digested with RQ-DNase (Promega). Complementary DNA was synthesized, using Oligo-dT primers, using a VERSO cDNA kit (Thermo Scientific).

High-throughput real-time quantitative PCR

High-throughput real-time qPCR was performed on a BioMark 96.96 Dynamic Array with TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) at the Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel). Three biological replicates were used for each treatment. Primers were designed with the Primer3 software, and synthesized by Metabion (Germany) and Hylabs (Israel) (see Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). The expression levels of the target genes were normalized to the control gene actin, as in Freiman et al. (2015), and analysed using the ΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Results

Effects of exogenous ABA application on physiological and metabolic changes during fig fruit ripening

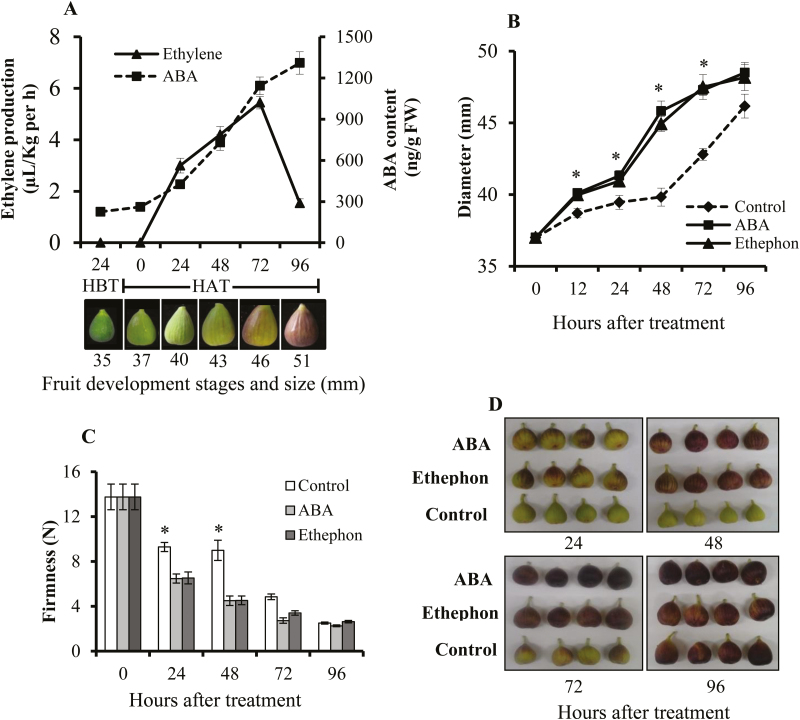

Fig fruit of 37 mm diameter with a greenish-yellow ostiole color were identified as being just before the rapid increase in endogenous ABA and initiation of ethylene production (Fig. 1A). Application of exogenous ABA or ethephon resulted in fruit with significantly larger diameters at 12, 24, 48, and 72 HAT compared to controls (Fig. 1B). ABA- and ethephon-treated fruit were significantly softer at 24 and 48 HAT compared to controls (Fig. 1C), and the change in fruit color associated with ripening started earlier than in controls (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Role of ABA in the fig fruit-ripening process. (A) Changes in endogenous ABA content and ethylene production during the onset of ripening. The fruit developmental stages are distinguished by the diameter and ostiole color. HBT, hours before treatment; HAT hours after treatment. Effects of exogenous ABA application on (B) fruit diameter and (C) firmness. (D) Images showing the different fruit colors and ripening stages at different times after treatment. Fruit treated with ethephon were used as a positive control. Data in (A–C) are means (±SE) of 9 fruit. Significant differences compared with the control were determined using Student’s t-test: *P<0.05.

Effects of exogenous ABA application on expression levels of genes of the ABA metabolism and ethylene biosynthesis pathways

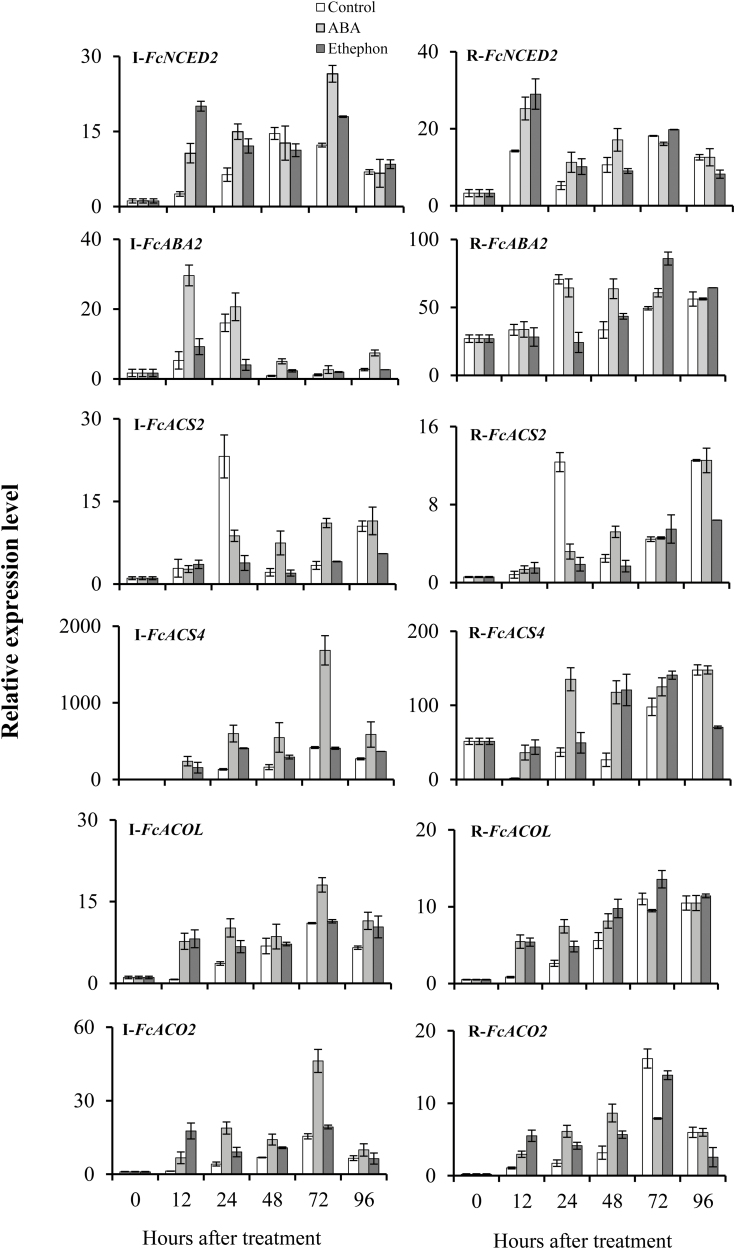

To understand the role of exogenous ABA in fig fruit ripening, the expression levels of six previously characterized (Rosianski et al., 2016a) ABA-biosynthesis and catabolism genes were determined (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1). Exogenous ABA application during the onset of ripening increased the expression levels of these genes. In particular, expression of FcNCED2, the key ABA-biosynthesis gene in fig fruit, was increased by ABA and ethephon treatments in both the inflorescences (4.2- and 7.9-fold change, respectively) and the receptacles (1.8- and 2.1-fold change, respectively) at 12 HAT, as compared to untreated controls (Fig. 2). FcNCED2 continued to be expressed at moderately high levels in ABA- and ethephon-treated fruit in the inflorescences (2.4- and 1.9-fold change, respectively) and the receptacles (2.2- and 1.9-fold change, respectively) at 24 HAT. In addition, moderately high expression of FcNCED2 was maintained at 72 HAT in inflorescences, but not in receptacles. ABA treatment also increased the expression of the ABA-biosynthesis gene FcABA2, to 5.6-fold that of controls in the inflorescence at 12 HAT (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, ethephon down-regulated FcABA2 expression at 24 HAT in the inflorescence (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Expression patterns of ABA-biosynthesis genes (FcNCED2 and FcABA2) and ethylene-biosynthesis genes (FcACS2, FcACS4, FcACOL, and FcACO2) in ABA- and ethephon-treated fig fruit. I, inflorescence; R, receptacle. Expression is relative to the actin gene. Treatment was applied before the onset of ripening. Data are means (±SE) of three biological replicates.

We then determined the effect of exogenous ABA application on ethylene-biosynthesis genes in the fruit (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1). FcACS4 was highly up-regulated by ABA and ethephon in the inflorescences (85.4- and 55.3-fold change, respectively) and in the receptacles (22.2- and 26.8-fold change, respectively) at 12 HAT, as compared to untreated controls. In addition, it was moderately up-regulated by ABA treatment in the inflorescences at 24, 48, and 72 HAT (4.5-, 3.4-, and 4.1-fold change, respectively). In ethephon-treated inflorescences, FcACS4 was moderately up-regulated at 24 HAT (3.1-fold change), whilst in the receptacles it was moderately up-regulated by ABA treatment at 24 and 48 HAT (3.7- and 4.4-fold change, respectively). Similarly, FcACS4 was moderately up-regulated at 48 HAT (4.5-fold change) in ethephon-treated receptacles (Fig. 2). The ethylene-biosynthesis gene FcACOL was highly up-regulated at 12 HAT by ABA and ethephon application in both the inflorescences (10.8- and 11.5-fold change, respectively) and the receptacles (6.6- and 6.5-fold change, respectively) compared to controls. At 24 HAT, it was moderately up-regulated by ABA in the inflorescences (2.8-fold change) and the receptacles (2.8-fold change). Similarly, compared to controls, FcACO2 was up-regulated by ABA at 12 and 24 HAT in both the inflorescences (5.3- and4.5-fold change, respectively) and the receptacles (2.8- and5.2-fold change, respectively), and it was also up-regulated by ethephon at 12 and 24 HAT in the inflorescences (13.9- and 2.2-fold change, respectively) and the receptacles (3.5- and 2.4-fold change, respectively) (Fig. 2). Interestingly, in the ABA-treated receptacles, FcSAM2 and FcSAM3 were moderately up-regulated (2.4- and 2.9-fold change, respectively) at 12 HAT (Supplementary Fig. S1).

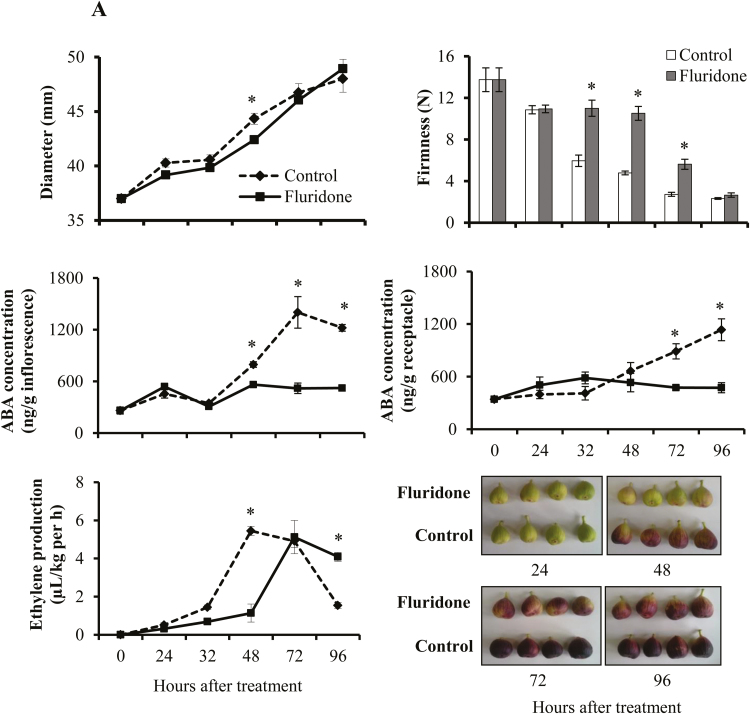

Effects of fluridone and NDGA application on physiological and metabolic alterations during fig fruit ripening

Fluridone treatment delayed the ripening of treated fig fruit; the fruit diameter was significantly smaller at 48 HAT and fruit remained significantly firmer at 32, 48, and 72 HAT compared to controls (Fig. 3A). The effect of fluridone on fruit firmness appeared to be transient as control and treated fruit showed no significant difference at 96 HAT. In addition, by 96 HAT ABA levels had increased 6- and 4-fold in the inflorescences and receptacles, respectively, of untreated fruit. Notably, we found that fluridone prevented ABA accumulation in both the inflorescences and receptacles, and delayed ethylene production.

Fig. 3.

Effects of (A) fluridone and (B) NDGA on diameter, firmness, ABA production in inflorescences and receptacles, and changes in color of fig fruit. Fluridone and NDGA were applied before the onset of ripening. Data are means (±SE) of 9 fruit. Significant differences compared with the control were determined using Student’s t-test: *P<0.05.

Similarly, NDGA also delayed ripening, with treated fruit having significantly smaller diameters and remaining firmer at 32, 48, and 72 HAT compared to controls (Fig. 3B). NDGA significantly delayed ABA accumulation as well as ethylene production in the inflorescences and receptacles.

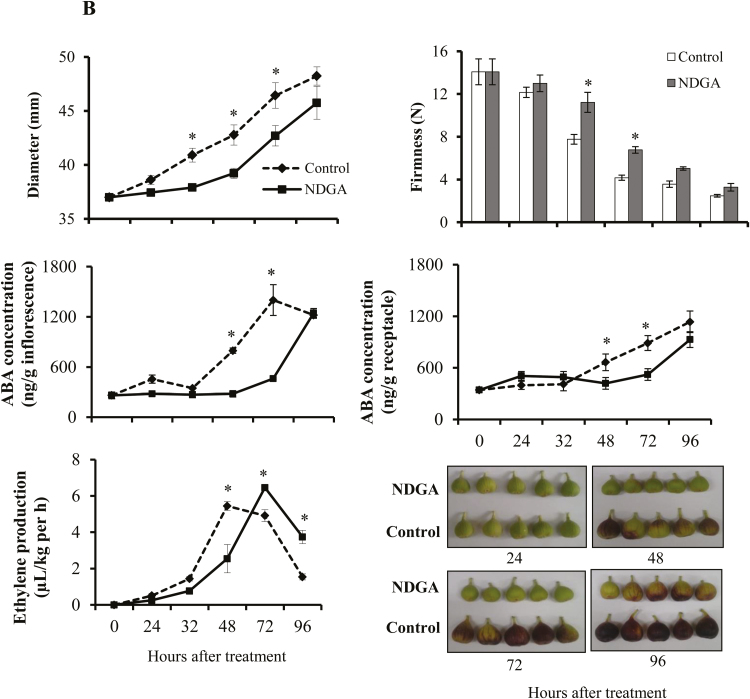

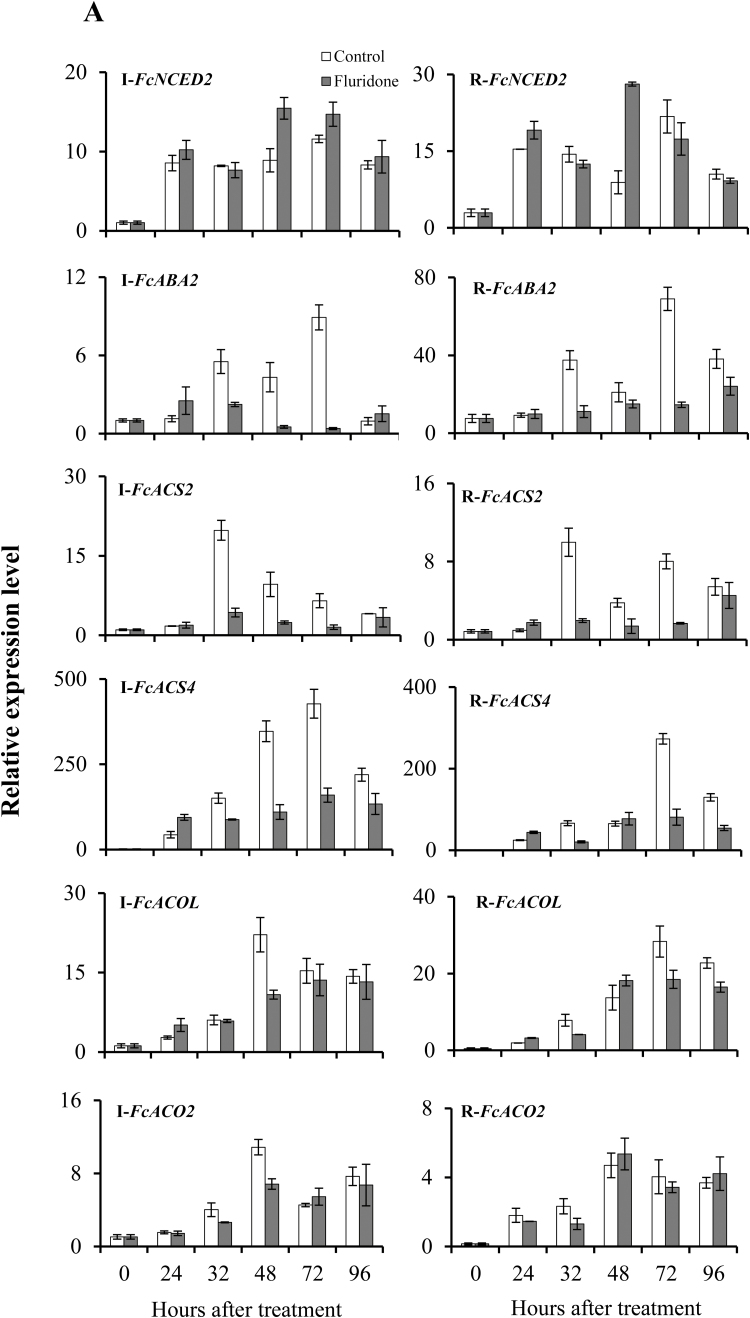

Effects of fluridone and NDGA on expression levels of ABA metabolic pathway and ethylene-biosynthesis genes

To investigate the changes in expression patterns of ripening-related genes caused by fluridone and NDGA, the expression of genes of the ABA biosynthetic and catabolic pathways and ethylene biosynthesis were examined (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S2). Fluridone did not significantly down-regulate FcNCED2 (Fig. 4A); however, compared to controls, it inhibited the expression of FcABA2 in inflorescences at 32, 48, and 72 HAT (2.5-, 8.4-, and 22.6-fold change, respectively) and in receptacles at 32 and 72 HAT (3.4- and 4.7-fold change, respectively). The ethylene-biosynthesis gene FcACS2 was down-regulated at 32, 48, and 72 HAT in both inflorescences (4.6-, 4-, and 4.3-fold change, respectively) and receptacles (5.1-, 2.7-, and 4.8-fold change, respectively) compared to controls. In addition, FcACS4 was down-regulated at 48 and 72 HAT in inflorescences (3.2- and 2.7-fold change, respectively) and at 32 and 72 HAT in receptacles (3.3- and 3.7-fold change, respectively). Similarly, expression levels of FcACOL and FcACO2 were slightly reduced at 48 HAT in inflorescences as compared to controls.

Fig. 4.

Expression patterns of ABA-biosynthesis genes (FcNCED2 and FcABA2) and ethylene-biosynthesis genes (FcACS2, FcACS4, FcACOL, and FcACO2) in (A) fluridone-treated and (B) NDGA-treated fig fruit. I, inflorescence; R, receptacle. Expression is relative to the actin gene. Treatment was applied before the onset of ripening. Data are means (±SE) of three biological replicates.

Interestingly, NDGA treatment caused down-regulation of FcNCED1 at 32, 48, and 72 HAT in the receptacles (3.6-, 7.1-, and 9.8-fold change, respectively; Supplementary Fig. S2B). In addition, FcNCED2 was significantly inhibited at 24, 32, and 48 HAT in inflorescences (18.4-, 3.8-, and 20-fold change, respectively) and in receptacles at 24 and 48 HAT (4.3- and 2.9-fold change, respectively; Fig. 4B). At 32 and 72 HAT, FcABA2 was inhibited in both inflorescences and receptacles. Expression of the ABA-catabolism gene FcABA8OX was elevated at 48, 72, and 96 HAT in both NDGA-treated inflorescences (13-, 5-, and 2.4-fold change, respectively) and receptacles (4.3-, 3.5-, and 3.2-fold change, respectively) compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The genes responsible for the first steps of ethylene biosynthesis, FcSAM2 and FcSAM3, were moderately down-regulated in inflorescences (2.8- and 2.4-fold change, respectively) and receptacles (2.9- and 2.2-fold change, respectively) at 12 HAT compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. S2B). In addition, FcACS2 and FcACS4 were down-regulated in inflorescences and receptacles of NDGA-treated fruit up to 72 HAT. In particular, FcACS2 was strongly down-regulated at 32 HAT (47.2-fold change) in inflorescences (Fig. 4B). Similarly, FcACS4 was strongly down-regulated by NDGA treatment at 24 and 32 HAT (24.7- and 16.5-fold change, respectively) in inflorescences. NDGA-treated fruit also showed strong down-regulation of FcACOL at 48 HAT (9.9-fold change) and FcACO2 at 32 HAT (8.6-fold change) in the inflorescences.

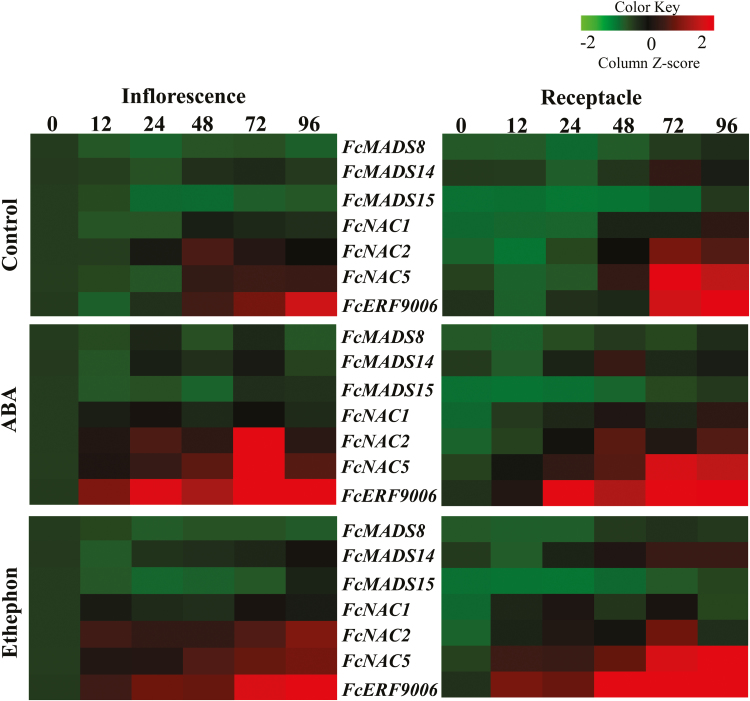

Effects of exogenous ABA application on expression levels of MADS-box, NAC, and ERF genes

To investigate the effects of ABA application on expression of potential ripening-regulator and ethylene signal-transduction genes, 15 MADS-box, 10 NAC, and 12 ERF genes were analysed (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figs. S3, S5, S7). FcMADS8, FcMADS14, and FcMADS15 were moderately up-regulated relative to controls by treatment with ABA and ethephon in inflorescences at 24 HAT (Fig. 5). Similarly, FcMADS8 and FcMADS14 were up-regulated in receptacles at 24 and 48 HAT, while FcMADS15 was up-regulated at 48 and 72 HAT. FcNAC1, FcNAC2, and FcNAC5 were up-regulated by ABA and ethephon treatment at 12 and 24 HAT in both inflorescences and receptacles, and FcERF9006 was up-regulated at 12, 24, and 48 HAT in both inflorescences and receptacles.

Fig. 5.

Expression patterns of MADS-box, NAC, and ERF genes in inflorescences and receptacles of fig fruit following on-tree exogenous ABA and ethephon application before the onset of ripening. The numbers at the top indicate the hours after treatment.

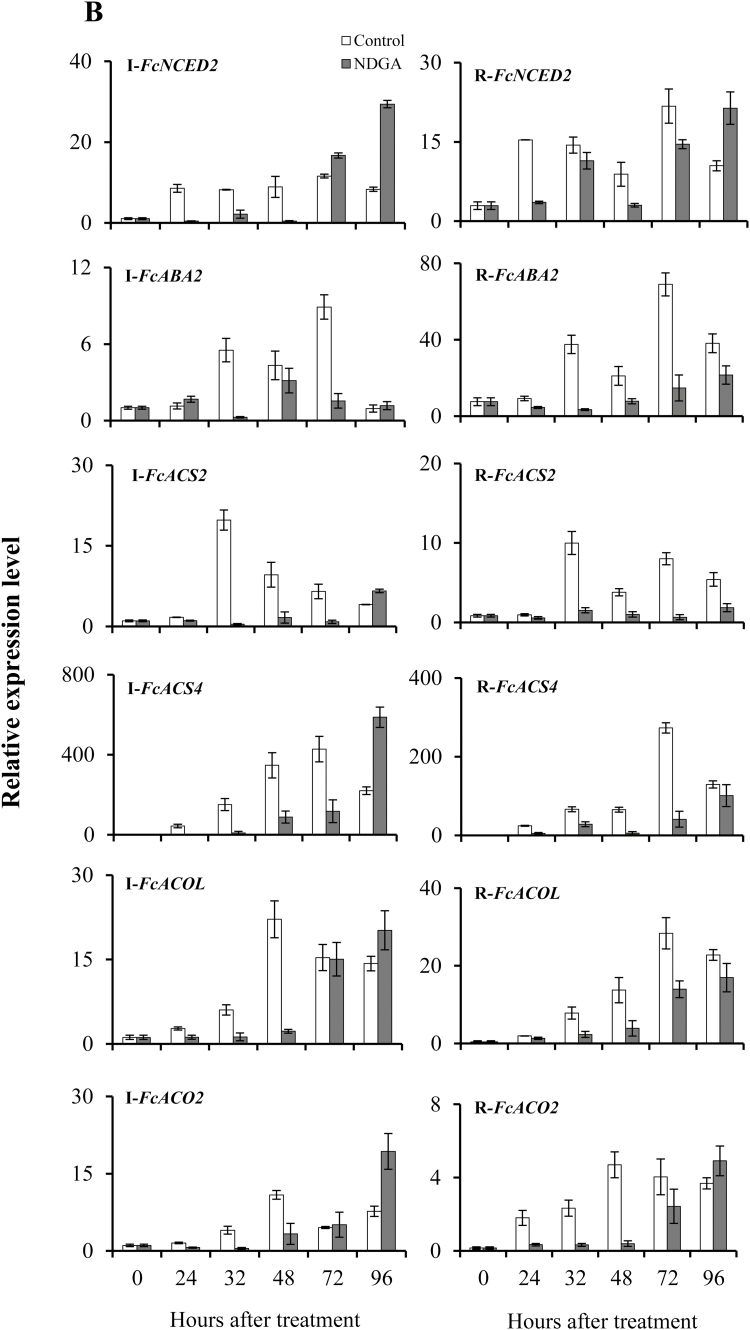

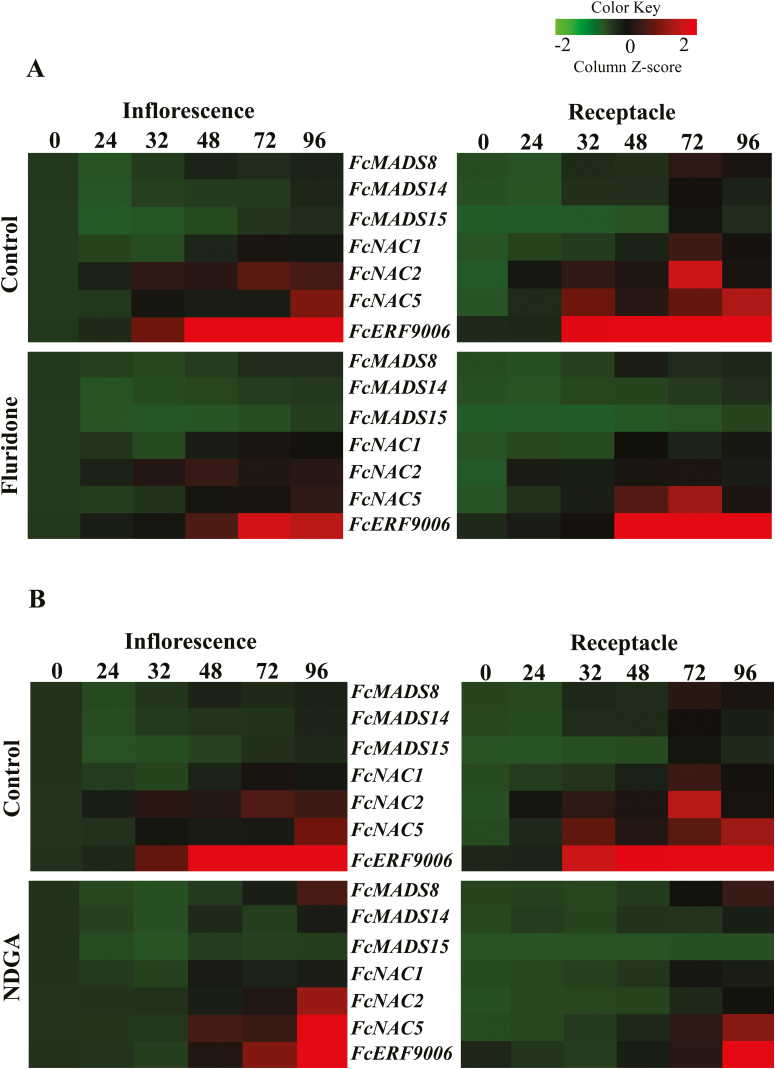

Effects of fluridone and NDGA on expression levels of MADS-box, NAC, and ERF genes

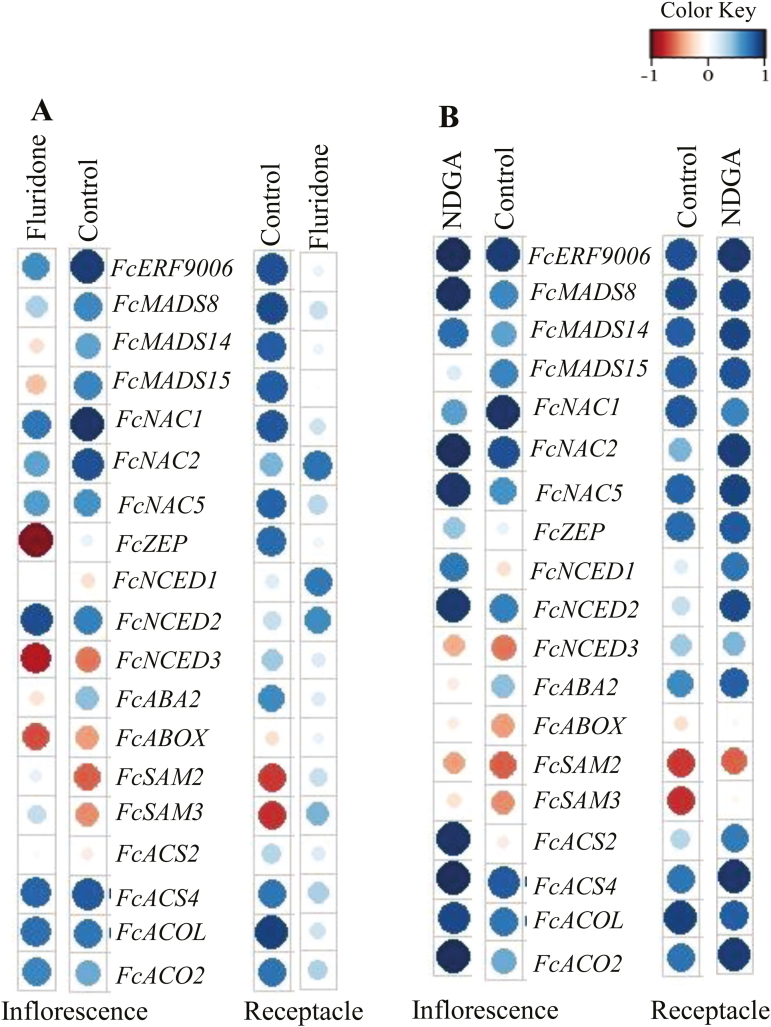

To determine the effects of fluridone and NDGA on the expression of potential ripening-regulator and ethylene signal-transduction genes, MADS-box, NAC and ERF genes were analysed (Fig. 6, Supplementary Figs. S4, S6, S8). Compared to controls, FcMADS8, FcMADS14, and FcMADS15 were moderately down-regulated by fluridone and NDGA treatments at 32 HAT in inflorescences and receptacles (Fig. 6). Similarly, FcNAC1 was slightly down-regulated by NDGA at 72 HAT in inflorescences, and also at 48 and 72 HAT in receptacles (Fig. 6B). There was no effect of fluridone on FcNAC1 in inflorescences, although this gene was down-regulated in receptacles at 72 HAT (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, FcNAC2 and FcNAC5 were down-regulated by NDGA at 32 HAT in both inflorescences and receptacles (Fig. 6B). In addition, FcNAC5 was down-regulated by fluridone at 32 HAT in inflorescences and receptacles (Fig. 6A). FcERF9006 was down-regulated by both fluridone and NDGA up to 72 HAT in both inflorescences and receptacles (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Expression patterns of MADS-box, NAC, and ERF genes in inflorescences and receptacles of fig fruit treated with (A) fluridone and (B) NDGA. The numbers indicate the hours after treatment.

Correlation between ripening-related genes and ABA in fluridone- and NDGA-treated fruit

Potential coordination between expression of ripening-related genes and ABA during fig fruit ripening was determined by Pearson’s correlation analysis. The analysis reflected the degree of coordination between gene expression and hormonal changes in the reproductive (inflorescence) and non-reproductive (receptacle) tissues of treated and non-treated fruit (Fig. 7). Fluridone treatment strongly altered the correlation between ABA and ripening-related genes in both tissues. In particular, FcSAM2 and FcSAM3 were negatively correlated with ABA in untreated fruit, whereas they were positively correlated in inflorescences and receptacles of fluridone-treated fruit (Fig. 7A). Fluridone negatively altered the correlation of FcABA2 with ABA in the inflorescence but not in the receptacle. In addition, FcZEP, FcMADS14, and FcMADS15 were negatively correlated with ABA in the inflorescence, whereas there was no correlation in the receptacle (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Graphical representation of the correlation matrix between genes and ABA during ripening in inflorescences and receptacles following (A) fluridone and (B) NDGA treatment. Pearson’s correlations were applied using the corrplot package. The color intensity and the size of the circle are proportional to the correlation coefficients. Positive and negative correlations are presented from blue to red, respectively (see key).

Interestingly, NDGA treatment resulted in a positive correlation of FcACS2 and FcNCED1 with ABA in the inflorescence; however, FcABA2 was negatively correlated with ABA in the NDGA-treated inflorescence (Fig. 7B). FcNCED3 was negatively correlated with ABA in inflorescences but positively correlated with ABA in the receptacles of all treated and untreated fruit. Furthermore, highly positive correlations of the key ABA-biosynthesis gene FcNCED2 and of the ethylene-biosynthesis genes FcACS4, FcACOL, and FcACO2 with ABA were detected in the inflorescences of treated and untreated fruit (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Fig fruit has traditionally been perceived as climacteric because its ripening process follows an increase in respiration rate and ethylene production (Chessa et al., 1992). However, ripening-related ethylene production has been found to increase in an unexpected auto-inhibitory manner after application of 1-MCP (Sozzi et al., 2005; Owino et al., 2006; Freiman et al., 2012). This paradox was explained by Freiman et al. (2015) in a molecular study of potential ripening-regulatory and ethylene-related genes in the receptacles (vegetative tissue) and inflorescences (reproductive tissue). More recently, endogenous ABA production has been observed to increase as the result of an increase in expression levels of ABA-biosynthesis genes at the onset of fruit ripening (Rosianski et al., 2016a). These data suggest that both ABA and ethylene are crucial players in the ripening process of figs, and we examined their potential interplay in the current study.

Exogenous ABA enhances fruit ripening by inducing the expression of genes in the ABA metabolism and ethylene biosynthesis pathways

Exogenous ABA treatment induced earlier onset of ripening, followed by a rapid increase in fruit diameter, softening, and purple coloration of the outer peel. Ethephon had the same effect and was used as a positive control (Fig. 1). Concomitant with the early onset of ripening, both ABA-biosynthesis genes (particularly FcNCED2) and ethylene-biosynthesis genes (particularly FcACS4, FcACOL, and FcACO2) were up-regulated as a result of exogenous ABA treatment in inflorescences and receptacles at 12 and 24 HAT (Fig. 2). These results are in general agreement with previous work on tomato where exogenous ABA was found to promote ripening by enhancing ethylene biosynthesis (Zhang et al., 2009b; Mou et al., 2016). An increase in endogenous autocatalytic ethylene production as a result of application of exogenous ABA is well known in several other fruits such as banana (Jiang et al., 2000), melon (Sun et al., 2013), peach, and grapes (Zhang et al., 2009a). Exogenous ABA also enhances the ripening process of non-climacteric strawberry fruit (Jia et al., 2011). In citrus, exogenous ABA accelerates ripening and induces expression of the ethylene-biosynthesis gene CsACO1. It also enhances fruit color, significantly decreases organic acid content, and increases sugar accumulation (Wang et al., 2016).

The key ABA-biosynthesis gene NCED has been cloned and characterized from various climacteric fruit species, such as apple (Lara and Vendrell, 2000), peach (Soto et al., 2013), tomato (Burbidge et al., 1999), and melon (Sun et al., 2013), as well as from non-climacteric fruit such as orange (Rodrigo et al., 2006), grape (Wheeler et al., 2009), and strawberry (Jia et al., 2011). In particular, in climacteric tomato fruit, LeNCED1 initiates ABA biosynthesis at the onset of fruit ripening, and may act as a ripening inducer (Zhang et al., 2009b). Similarly, FaNCED1 and FaNCED2 have been reported to regulate ABA biosynthesis during the onset of ripening in non-climacteric strawberry fruit (Jia et al., 2011; Ji et al., 2012). To date, three genes encoding the NCED enzyme have been isolated from the inflorescence and receptacle tissues of both pollinated and parthenocarpic fig fruit during ripening (Rosianski et al., 2016a). Our current study showed that expression of FcNCED2 was up-regulated as early as 12 HAT, while expression of the ethylene-biosynthesis gene FcACS4 was only up-regulated at 24 HAT in control fruit. In addition, another ABA-biosynthesis gene, FcABA2, showed a similar temporal pattern of up-regulation, but only in control fruit inflorescences (Fig. 2). The simultaneous up-regulation of key ABA- and ethylene-biosynthesis genes, especially in the inflorescence, suggested that there was major up-regulation of ethylene-biosynthesis genes after the up-regulation of ABA-biosynthesis genes, as seen in tomato (Zhang et al., 2009b; Mou et al., 2016), and confirmed that the ethylene-dependent ripening process in fig is coordinated by the reproductive part of the fruit—the inflorescence—as stated by Freiman et al. (2015) and Rosianski et al. (2016a).

Fluridone and NDGA reduce expression of ABA-biosynthesis genes, thereby altering fruit ripening

Fruit treated with fluridone showed delayed onset of ripening, followed by a slower increase in diameter and a slower decrease in firmness of the fruit compared with controls (Fig. 3A). Endogenous ABA accumulation and ethylene production were strongly suppressed as a result of the down-regulation of ABA- and ethylene-biosynthesis genes. Similarly, application of NDGA reduced the expression of ABA-biosynthesis genes. Specifically, NDGA reduced the expression of both FcNCED2 and FcABA2, whereas fluridone only lowered the expression level of FcABA2 (Fig. 4). Although fluridone and NDGA act in different ways to suppress ABA biosynthesis, the ethylene-biosynthesis genes FcACS2, 4, FcACOL, and FcACO2 were strongly down-regulated by both inhibitors, as also occurs in the fruit of tomato (Zhang et al., 2009b) and strawberry (Jia et al., 2011). In tomato, down-regulation of SlNCED1 by RNAi leads to down-regulation of genes encoding major cell wall-catabolic enzymes during ripening, resulting in firmer fruit (Sun et al., 2012), whilst in strawberry, down-regulation of FaNCED1 results in a significant decrease in ABA levels and in fruit that lack color (Jia et al., 2011). As with SlNCED1 in tomato (Sun et al., 2012), FcNCED2 in fig was down-regulated by NDGA (FcNCED2 shares 71.72% identity with SlNCED1, Supplementary Fig. S9); it is therefore plausible that NDGA treatment altered the expression of genes related to regulation of cell wall modification in fig: further experiments are needed to clarify this point. Application of NDGA to fig up-regulated the ABA-catabolism pathway gene FcABA8OX, which could have been responsible for the decrease in total active ABA accumulation. This would be in agreement with work in tomato by Mou et al. (2016), where ABA8OX was slightly up-regulated after NDGA treatment; however, no effect of fluridone was observed.

Responses of potential ripening regulators to exogenous ABA, fluridone, and NDGA treatments

The ripening process in fleshy fruits is regulated by plant hormones and involves numerous transcription factors (Adams-Phillips et al., 2004; Karlova et al., 2014). Members of the MADS-box gene family have been found to regulate ripening in several climacteric species: RIN and TAGL1 in tomato, PLENA in Prunus persica (peach), MADS1–5 in banana, and MADS8 and MADS9 in apple (Vrebalov et al., 2002, 2009; Itkin et al., 2009; Tadiello et al., 2009; Elitzur et al., 2010; Ireland et al., 2013). In addition, genes from the MADS-box gene family are involved in non-climacteric fruit ripening, such as MADS9 in strawberry (Seymour et al., 2011). In the unique climacteric fig fruit, eight MADS-box transcripts have been identified and partially isolated from fruit developing on the tree (Freiman et al., 2014). An in-depth study of the transcriptome data of fig fruit during different ripening stages revealed seven new MADS-box transcripts (Rosianski et al., 2016a). In addition, FcMADS8, which is highly similar to SlRIN, shows an increase in expression during the ripening of both fig inflorescences and receptacles (Freiman et al., 2015). Here, we found that FcMADS8, 14, and 15 were moderately up-regulated by ABA application in both inflorescences and receptacles at 24 HAT, whereas they were inhibited by fluridone and NDGA (Figs 5, 6). This was similar to tomato fruit, where expression of MADS-RIN is elevated by exogenous ABA, and suppressed by NDGA when endogenous ABA is inhibited (Mou et al., 2016).

Among the 27 NAC transcripts of fig fruit described by Freiman et al. (2014), FcNAC1, 2, and 5 showed moderate up-regulation by ABA treatment (Fig. 5). On the other hand, FcNAC2 and 5 were down-regulated by both fluridone and NDGA treatments while FcNAC1 was down-regulated by NDGA only in the receptacle (Fig. 6). A similar effect has been noted in tomato fruit where NOR, a member of the NAC domain family that functions upstream of ethylene in the tomato fruit ripening cascade, is elevated by exogenous ABA and suppressed by NDGA (Mou et al., 2016). In this context, our results suggested that FcNAC1, 2, and 5 interacted in their role in fig fruit ripening, similar to MaNAC1 and MaNAC2 in banana fruit ripening via interaction with the ethylene-signaling pathway (Shan et al., 2012). Furthermore, overexpression of SlNAC1 has been shown to regulate tomato fruit ripening through both ethylene-dependent and ABA-dependent pathways (Ma et al., 2014). Reduced expression of SlNAC4 by RNAi in tomato results in delayed fruit ripening, suppression of chlorophyll breakdown, a decrease in ethylene biosynthesis by a reduction in the expression of ethylene-biosynthesis genes, and a reduction in carotenoids by alterations in fluxes in the carotenoid pathway (Zhu et al., 2014). Surprisingly, Kou et al. (2014) showed that SlNAC4 is down-regulated by ABA treatment whereas SlNAC5, 6, 7, and 9 are up-regulated in tomato fruit.

The ERFs are a large family of transcription factors that includes gene repressors and activators, with a degree of functional redundancy among its members (Klee and Giovannoni, 2011; Licausi et al., 2013). In fig fruit, ERFs are positive ripening regulators, except for FcERF12185 that is only highly expressed at the fully ripe stage and is probably not responsible for the climacteric rise in ethylene or the metabolic ripening processes in the earlier stages (Freiman et al., 2015). Among the ERF transcripts isolated by Freiman et al. (2015), we demonstrated here that FcERF9006 expression is up-regulated by exogenous ABA and ethephon treatment, whereas it is down-regulated by fluridone and NDGA in both inflorescences and receptacles (Figs 5, 6). In climacteric tomato, LeERF2, LeERF3, and LeERF4 are down-regulated by ABA treatment and LeERF4 is more highly expressed after NDGA treatment (Mou et al., 2016). Indeed, temporary down-regulation of most FcERFs was observed in the unique climacteric fig fruit following pre-harvest treatment with 1-MCP (Freiman et al., 2015).

Non-climacteric characteristics of fig fruit exclude them from the conventional climacteric category

Despite the classification of fig fruit as climacteric, when harvested prior to complete ripening they never reach the commercially desirable parameters of size, color, flavor, and texture (Flaishman et al., 2008). Surprisingly, 1-MCP markedly enhances ethylene production in figs (Sozzi et al., 2005; Owino et al., 2006; Freiman et al., 2012), similar to its effect in non-climacteric fruit such as citrus (McCollum and Maul, 2007). This confirms the non-climacteric, auto-inhibitory regulation of ethylene synthesis, rather than the autocatalytic pattern typical of climacteric fruit (Freiman et al., 2012). Apart from ethylene, several recent studies have shown that ABA plays an important role in the regulation of fruit development and ripening in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruit (Zhang et al., 2009a, 2009b; Sun et al., 2012; Leng et al., 2014). In the mature fig fruit, endogenous ABA is present before ethylene is produced, and is supposed to trigger the ripening process (Fig. 1A). The increase in accumulation of endogenous ABA during the onset of fig ripening is similar to that in other climacteric fruit such as tomato, avocado, and apple (Chernys and Zeevaart, 2000; Lara and Vendrell, 2000; Srivastava and Handa, 2005; Zhang et al., 2009b; Leng et al., 2014). However, instead of tapering off after the onset of ripening, as in climacteric fruit, the endogenous ABA content in control plants continued to rise until the fig fruit was fully ripe, as in non-climacteric strawberry fruit (Fig. 1A; Jia et al., 2011). Interestingly, this phenomenon was observed in both the reproductive inflorescence tissue and the vegetative receptacle tissue, with high expression of major ABA-biosynthesis pathway genes (Figs 2, 4). On the other hand, expression of ethylene-related genes was different for the two tissues, with only the inflorescence showing expression similar to that in climacteric fruit (Freiman et al., 2015). In agreement with previous studies, our results showed that ethylene was produced at high levels at the 30–50% ripening stage, with significantly high expression of the ethylene-biosynthesis gene FcACS4 in the inflorescence, although expression levels rose in both tissues (Freiman et al., 2012, 2015; Fig. 1A). Increased expression of ethylene-biosynthesis genes was also observed in petioles (vegetative tissues) of fruit at different ripening stages—from green to fully ripe (Supplementary Fig. S10). These expression levels were very low compared to those in the inflorescences and receptacles, and they played no part in fruit ripening. Similarly, very low expression of ethylene-biosynthesis genes in receptacles relative to inflorescences would lead to the production of minor amounts of ethylene, which might not be enough for the ripening process, but a high amount of endogenous ABA production until full ripeness, as in strawberry, could lead to non-climacteric ripening by promoting sugar accumulation, fruit pigmentation, and softening, as described in a non-climacteric fruit-ripening model (Li et al., 2011). This distinct mechanism in the receptacle could be synchronized by the ABA-biosynthesis genes FcZEP, FcNCED1, and FcNCED3, the expression of which was positively correlated with ABA in the receptacle but negatively correlated in the inflorescence during natural ripening of untreated fruit (Fig. 7). Different ripening mechanisms for specific organs have also been reported in strawberry, where ethylene is involved in the ripening of achenes (reproductive organ) but not the receptacles (vegetative organ) (Merchante et al., 2013). Indeed, strawberry is considered a non-climactic fruit where ABA promotes ripening by increasing its endogenous levels until full ripeness (Jia et al., 2011). This unique characteristic of ripening, showing both climacteric and non-climacteric behavior, has also been reported in ‘Elizabeth’ melon (Cucumis melo), although it is regarded as a climacteric fruit (Sun et al., 2013).

Non-climacteric fruit are considered to be a separate group that does not follow the typical climacteric ripening pattern. However, the identification of MADS-box genes in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruit suggests that at least some aspects of ripening are shared between these two categories (Daminato et al., 2013). In strawberry, a MADS-box SEPALLATA gene (SEP1/2) is needed for normal fruit development and ripening (Seymour et al., 2011). Similarly, in banana, which is classified as a climacteric fruit, the MADS-box SEP3 gene also displays ripening-related expression (Elitzur et al., 2010). In the fig fruit, FcMADS8 expression increases during ripening on the tree and is inhibited by 1-MCP treatment (Freiman et al., 2015). Interestingly, FcMADS8 was inhibited by fluridone and NDGA in the inflorescence at 32 and 48 HAT (Fig. 6). During the ripening of pepper fruit, genes involved in ethylene biosynthesis are not induced; however, genes downstream of ethylene perception, such as cell wall-related genes, ERF3, and carotenoid-biosynthesis genes, are up-regulated (Osorio et al., 2012). In fig fruit, FcERF12185 is up-regulated by 1-MCP treatment during ripening and may play a role in regulating ethylene-synthesis system 1 and in causing the non-climacteric behavior of ethylene production (Freiman et al., 2015). However, expression of FcERF12185 was not affected by application of ABA, fluridone, or NDGA in our current study (Supplementary Figs S7, S8). In contrast, the expression level of FcERF9006 was altered by application of ABA, fluridone, and NDGA, which suggests a role for this gene in non-climacteric and/or ABA-dependent ripening of fig fruit (Figs 5, 6).

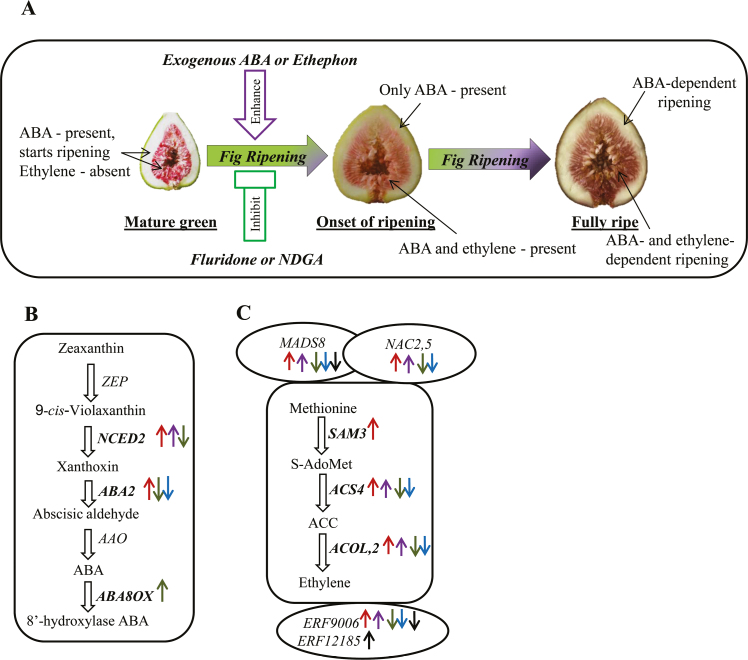

In conclusion, involvement of ABA during fig fruit ripening was confirmed in our study by observed alterations in ripening as the result of the application of exogenous ABA, ethephon, fluridone, and NDGA. The unique ripening nature of fig fruit, in which two tissues act separately, is illustrated in a proposed model (Fig. 8A). The alterations in the expression levels of ABA-metabolic pathway, ethylene-biosynthesis, MADS-box, NAC, and ERF genes in the fruit by on-tree application of ABA, ethephon, fluridone, NDGA, and 1-MCP (Freiman et al., 2015) are summarized in Fig. 8B, C. A highly positive correlation of the ABA-biosynthesis gene FcNCED2 and the ethylene-biosynthesis gene FcACS4 with endogenous ABA in the inflorescence demonstrates a key role in fig fruit ripening. We plan to further utilize these as candidate genes for genome editing to slow down the ripening process.

Fig. 8.

Proposed model of ABA-regulatory and -biosynthesis genes in fig fruit. (A) ABA interplay with ethylene in fig fruit during ripening. (B) Changes in activity of ABA metabolic pathway genes in the fruit following on-tree exogenous application of ABA, ethephon, NDGA and fluridone. (C) Changes in activity of ethylene-biosynthesis, MADS-box, NAC, and ERF gene in the fruit following on-tree exogenous application of ABA, ethephon, NDGA, fluridone, and 1-MCP (Freiman et al., 2015). Downward arrows indicate down-regulated genes in treated fruit compared to untreated controls; upward arrows indicate up-regulated genes. The arrows are color-coded as follows: red, ABA; purple, ethephon; green, NDGA; blue, fluridone; black, 1MCP.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. Primers used for high-throughput real-time qPCR.

Fig. S1. Expression pattern of ABA-metabolism and ethylene-biosynthesis genes in ABA- and ethephon-treated fig fruit.

Fig. S2. Expression pattern of ABA-metabolism and ethylene-biosynthesis in fluridone- and NDGA-treated fig fruit.

Fig. S3. Expression pattern of MADS-box genes in inflorescence and receptacle tissues following ABA and ethephon treatment.

Fig. S4. Expression pattern of MADS-box genes in inflorescence and receptacle tissues following fluridone and NDGA application.

Fig. S5. Expression pattern of NAC genes in inflorescence and receptacle tissues following ABA and ethephon application.

Fig. S6. Expression pattern of NAC genes in inflorescence and receptacle tissues following fluridone and NDGA application.

Fig. S7. Expression pattern of ERF genes in inflorescence and receptacle tissues following ABA and ethephon application.

Fig. S8. Expression pattern of ERF genes in inflorescence and receptacle tissues following fluridone and NDGA application.

Fig. S9. Alignment of FcNCED2 amino acid sequence and SlNCED1 protein.

Fig. S10. Expression of ethylene-biosynthesis genes in the petiole of fig fruits at different developmental stages during ripening.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Adi Faigenboim for help in data analysis. Funding was provided by the Ministry of Agriculture, Bet Dagan, Israel.

References

- Adams-Phillips L, Barry C, Giovannoni J. 2004. Signal transduction systems regulating fruit ripening. Trends in Plant Science 9, 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban T, Ishimaru M, Kobayashi S, Shiozaki S, Goto-Yamamoto N, Horiuchi S. 2003. Abscisic acid and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid affect the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes in ‘Kyoho’ grape berries. Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology 78, 586–589. [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge A, Grieve TM, Jackson A, Thompson A, McCarty DR, Taylor IB. 1999. Characterization of the ABA-deficient tomato mutant notabilis and its relationship with maize Vp14. The Plant Journal 17, 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernys JT, Zeevaart JA. 2000. Characterization of the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene family and the regulation of abscisic acid biosynthesis in avocado. Plant Physiology 124, 343–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessa I, Nieddu G, Schirra M. 1992. Growth and ripening of main-crop fig. Advances in Horticultural Science 6, 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Daminato M, Guzzo F, Casadoro G. 2013. A SHATTERPROOF-like gene controls ripening in non-climacteric strawberries, and auxin and abscisic acid antagonistically affect its expression. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 3775–3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elitzur T, Vrebalov J, Giovannoni JJ, Goldschmidt EE, Friedman H. 2010. The regulation of MADS-box gene expression during ripening of banana and their regulatory interaction with ethylene. Journal of Experimental Botany 61, 1523–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaishman MA, Rodov V, Stover E. 2008. The fig: botany, horticulture, and breeding. In: Janick J, ed. Horticultural reviews, vol. 34. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 113–196. [Google Scholar]

- Freiman ZE, Doron-Faigenboim A, Dasmohapatra R, Yablovitz Z, Flaishman MA. 2014. High-throughput sequencing analysis of common fig (Ficus carica L.) transcriptome during fruit ripening. Tree Genetics & Genomes 10, 923–935. [Google Scholar]

- Freiman ZE, Rodov V, Yablovitz Z, Horev B, Flaishman MA. 2012. Preharvest application of 1-methylcyclopropene inhibits ripening and improves keeping quality of ‘Brown Turkey’ figs (Ficus carica L.). Scientia Horticulturae 138, 266–272. [Google Scholar]

- Freiman ZE, Rosianskey Y, Dasmohapatra R, Kamara I, Flaishman MA. 2015. The ambiguous ripening nature of the fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit: a gene-expression study of potential ripening regulators and ethylene-related genes. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 3309–3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni J. 2001. Molecular biology of fruit maturation and ripening. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 52, 725–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribaldi M, Gény L, Delrot S, Schubert A. 2010. Proteomic analysis of the effects of ABA treatments on ripening Vitis vinifera berries. Journal of Experimental Botany 61, 2447–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland HS, Yao JL, Tomes S, Sutherland PW, Nieuwenhuizen N, Gunaseelan K, Winz RA, David KM, Schaffer RJ. 2013. Apple SEPALLATA1/2-like genes control fruit flesh development and ripening. The Plant Journal 73, 1044–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itkin M, Seybold H, Breitel D, Rogachev I, Meir S, Aharoni A. 2009. TOMATO AGAMOUS-LIKE 1 is a component of the fruit ripening regulatory network. The Plant Journal 60, 1081–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola L, Pirttilä AM, Halonen M, Hohtola A. 2001. Isolation of high quality RNA from bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) fruit. Molecular Biotechnology 19, 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K, Chen P, Sun L, et al. 2012. Non-climacteric ripening in strawberry fruit is linked to ABA, FaNCED2 and FaCYP707A1. Functional Plant Biology 39, 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia HF, Chai YM, Li CL, Lu D, Luo JJ, Qin L, Shen YY. 2011. Abscisic acid plays an important role in the regulation of strawberry fruit ripening. Plant Physiology 157, 188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Hartung W. 2008. Long-distance signalling of abscisic acid (ABA): the factors regulating the intensity of the ABA signal. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Joyce DC. 2003. ABA effects on ethylene production, PAL activity, anthocyanin and phenolic contents of strawberry fruit. Plant Growth Regulation 39, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Joyce DC, Macnish AJ. 2000. Effect of abscisic acid on banana fruit ripening in relation to the role of ethylene. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 19, 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlova R, Chapman N, David K, Angenent GC, Seymour GB, de Maagd RA. 2014. Transcriptional control of fleshy fruit development and ripening. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 4527–4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee HJ, Giovannoni JJ. 2011. Genetics and control of tomato fruit ripening and quality attributes. Annual Review of Genetics 45, 41–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou XH, Wang S, Wu MS, Guo RZ, Xue ZH, Meng N, Tao XM, Chen MM, Zhang YF. 2014. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of NAC family transcription factors in tomato. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 32, 501–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Khurana A, Sharma AK. 2014. Role of plant hormones and their interplay in development and ripening of fleshy fruits. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 4561–4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara I, Vendrell M. 2000. Development of ethylene-synthesizing capacity in preclimacteric apples: interaction between abscisic acid and ethylene. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 125, 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Leng P, Yuan B, Guo Y. 2014. The role of abscisic acid in fruit ripening and responses to abiotic stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 4577–4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Jia H, Chai Y, Shen Y. 2011. Abscisic acid perception and signaling transduction in strawberry: a model for non-climacteric fruit ripening. Plant Signaling & Behavior 6, 1950–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licausi F, Ohme-Takagi M, Perata P. 2013. APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. New Phytologist 199, 639–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆Ct method. Methods 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Dai SJ, Ren J, et al. 2014. The role of ABA in the maturation and postharvest life of a nonclimacteric sweet cherry fruit. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 33, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Feng H, Meng X, Li D, Yang D, Wu C, Meng Q. 2014. Overexpression of tomato SlNAC1 transcription factor alters fruit pigmentation and softening. BMC Plant Biology 14, 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marei N, Crane JC. 1971. Growth and respiratory response of fig (Ficus carica L. cv. Mission) fruits to ethylene. Plant Physiology 48, 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum G, Maul P. 2007. 1-Methylcyclopropene inhibits degreening but stimulates respiration and ethylene biosynthesis in grapefruit. Hortscience 42, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Merchante C, Vallarino JG, Osorio S, et al. 2013. Ethylene is involved in strawberry fruit ripening in an organ-specific manner. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 4421–4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou WS, Li DD, Bu JW, Jiang YY, Khan ZU, Luo ZS, Mao LC, Ying TJ. 2016. Comprehensive analysis of ABA effects on ethylene biosynthesis and signaling during tomato fruit ripening. PLoS ONE 11, e0154072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio S, Alba R, Nikoloski Z, Kochevenko A, Fernie AR, Giovannoni JJ. 2012. Integrative comparative analyses of transcript and metabolite profiles from pepper and tomato ripening and development stages uncovers species-specific patterns of network regulatory behavior. Plant Physiology 159, 1713–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owino WO, Manabe Y, Mathooko FM, Kubo Y, Inaba A. 2006. Regulatory mechanisms of ethylene biosynthesis in response to various stimuli during maturation and ripening in fig fruit (Ficus carica L.). Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 44, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo MJ, Alquezar B, Zacarías L. 2006. Cloning and characterization of two 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase genes, differentially regulated during fruit maturation and under stress conditions, from orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck). Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosianski Y, Doron-Faigenboim A, Freiman ZE, Lama K, Milo-Cochavi S, Dahan Y, Kerem Z, Flaishman MA. 2016a. Tissue-specific transcriptome and hormonal regulation of pollinated and parthenocarpic fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit suggest that fruit ripening is coordinated by the reproductive part of the syconium. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosianski Y, Freiman ZE, Cochavi SM, Yablovitz Z, Kerem Z, Flaishman MA. 2016b. Advanced analysis of developmental and ripening characteristics of pollinated common-type fig (Ficus carica L.). Scientia Horticulturae 198, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH, Qin X, Zeevaart JA. 2003. Elucidation of the indirect pathway of abscisic acid biosynthesis by mutants, genes, and enzymes. Plant Physiology 131, 1591–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M, Koshiba T. 2011. Transport of ABA from the site of biosynthesis to the site of action. Journal of Plant Research 124, 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setha S. 2012. Roles of abscisic acid in fruit ripening. Walailak Journal of Science and Technology 9, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Setha S, Kondo S, Hirai N, Ohigashi H. 2005. Quantification of ABA and its metabolites in sweet cherries using deuterium-labeled internal standards. Plant Growth Regulation 45, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour GB, Ryder CD, Cevik V, Hammond JP, Popovich A, King GJ, Vrebalov J, Giovannoni JJ, Manning K. 2011. A SEPALLATA gene is involved in the development and ripening of strawberry (Fragaria×ananassa Duch.) fruit, a non-climacteric tissue. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 1179–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan W, Kuang JF, Chen L, et al. 2012. Molecular characterization of banana NAC transcription factors and their interactions with ethylene signalling component EIL during fruit ripening. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 5171–5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto A, Ruiz KB, Ravaglia D, Costa G, Torrigiani P. 2013. ABA may promote or delay peach fruit ripening through modulation of ripening- and hormone-related gene expression depending on the developmental stage. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 64, 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozzi GO, Abrajan-Villasenor MA, Trinchero GD, Fraschina AA. 2005. Postharvest response of ‘Brown Turkey’ figs (Ficus carica L.) to the inhibition of ethylene perception. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 85, 2503–2508. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Handa AK. 2005. Hormonal regulation of tomato fruit development: a molecular perspective. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 24, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Storey WB, Enderud JE, Saleeb WF, Nauer EM. 1977. The fig: its biology, history, culture, and utilization. Riverside, CA: Jurupa Mountains Cultural Center. [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Sun Y, Zhang M, et al. 2012. Suppression of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, which encodes a key enzyme in abscisic acid biosynthesis, alters fruit texture in transgenic tomato. Plant Physiology 158, 283–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Chen P, Duan CR, et al. 2013. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding key enzymes of abscisic acid metabolism during melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit development and ripening. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 32, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tadiello A, Pavanello A, Zanin D, Caporali E, Colombo L, Rotino GL, Trainotti L, Casadoro G. 2009. A PLENA-like gene of peach is involved in carpel formation and subsequent transformation into a fleshy fruit. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 651–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor IB, Sonneveld T, Bugg TDH, Thompson AJ. 2005. Regulation and manipulation of the biosynthesis of abscisic acid, including the supply of xanthophyll precursors. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 24, 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Vrebalov J, Pan IL, Arroyo AJ, et al. 2009. Fleshy fruit expansion and ripening are regulated by the Tomato SHATTERPROOF gene TAGL1. The Plant Cell 21, 3041–3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrebalov J, Ruezinsky D, Padmanabhan V, White R, Medrano D, Drake R, Schuch W, Giovannoni J. 2002. A MADS-box gene necessary for fruit ripening at the tomato ripening-inhibitor (Rin) locus. Science 296, 343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XH, Yin W, Wu JX, Chai LJ, Yi HL. 2016. Effects of exogenous abscisic acid on the expression of citrus fruit ripening-related genes and fruit ripening. Scientia Horticulturae 201, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S, Loveys B, Ford C, Davies C. 2009. The relationship between the expression of abscisic acid biosynthesis genes, accumulation of abscisic acid and the promotion of Vitis vinifera L. berry ripening by abscisic acid. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 15, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zaharah SS, Singh Z, Symons GM, Reid JB. 2012. Role of brassinosteroids, ethylene, abscisic acid, and indole-3-acetic acid in mango fruit ripening. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 31, 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Leng P, Zhang G, Li X. 2009a. Cloning and functional analysis of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) genes encoding a key enzyme during abscisic acid biosynthesis from peach and grape fruits. Journal of Plant Physiology 166, 1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Yuan B, Leng P. 2009b. The role of ABA in triggering ethylene biosynthesis and ripening of tomato fruit. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 1579–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Chen G, Zhou S, Tu Y, Wang Y, Dong T, Hu Z. 2014. A new tomato NAC (NAM/ATAF1/2/CUC2) transcription factor, SlNAC4, functions as a positive regulator of fruit ripening and carotenoid accumulation. Plant & Cell Physiology 55, 119–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.