Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 2

Version (3) of the manuscript is significantly shorter following reviewer suggestions. Other changes include to keep the focus on the objective of providing a synopsis of outcomes in the 22 to <28 weeks gestational age window in a low resource setting, based on gestation (not birth weight). This has been clarified by a new version of Supplementary File 1. The most recent comments asked for clarification of the two groups that are described in the manuscript: miscarriage (late expulsion, non-viable <22 weeks) and extreme preterm birth (expulsed 22 to <28, viable at 22 weeks); and for stillbirth, how signs of life were determined. The reviewer also commented on the limitations of the data, particularly women registered to antenatal care but for whom no outcome is available. This has been addressed in the first section of results and discussion with other limitations mentioned later in the discussion. This version of the manuscript continues to support the WHO cut-point of 28 weeks gestation for global/international reporting of stillbirth. The manuscript confronts this problematic gestational age window when resources are constrained. An additional affiliation (Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute) for co-author Verena I. Carra has been added.

Abstract

Background : No universal demarcation of gestational age distinguishes miscarriage and stillbirth or extreme preterm birth (exPTB). This study provides a synopsis of outcome between 22 to <28 weeks gestation from a low resource setting.

Methods : A retrospective record review of a population on the Thailand-Myanmar border was conducted. Outcomes were classified as miscarriage, late expulsion of products between 22 to < 28 weeks gestation with evidence of non-viability (mostly ultrasound absent fetal heart beat) prior to 22 weeks; or exPTB (stillbirth/live born) between 22 to < 28 weeks gestation when the fetus was viable at ≥22 weeks. Termination of pregnancy and gestational trophoblastic disease were excluded.

Results : From 1995-2015, 80.9% (50,046/ 61,829) of registered women had a known pregnancy outcome, of whom 99.8% (49,931) had a known gestational age. Delivery between 22 to <28 weeks gestation included 0.9% (472/49,931) of pregnancies after removing 18 cases (3.8%) who met an exclusion criteria. Most pregnancies had an ultrasound: 72.5% (n=329/454); 43.6% (n=197) were classified as miscarriage and 56.4% (n=257) exPTB. Individual record review of miscarriages estimated that fetal death had occurred at a median of 16 weeks, despite late expulsion between 22 to <28 weeks. With available data (n=252, 5 missing) the proportion of stillbirth was 47.6% (n=120), congenital abnormality 10.5% (24/228, 29 missing) and neonatal death was 98.5% (128/131, 1 missing). Introduction of ultrasound was associated with a 2-times higher odds of classification of outcome as exPTB rather than miscarriage.

Conclusion : In this low resource setting few (<1%) pregnancy outcomes occurred in the 22 to <28 weeks gestational window; four in ten were miscarriage (late expulsion) and neonatal mortality approached 100%. In the scale-up to preventable newborns deaths (at least initially) greater benefits will be obtained by focusing on the viable newborns of ≥ 28 weeks gestation.

Keywords: extreme preterm birth, limited-resource, low-income, marginalized, miscarriage, neonatal death, stillbirth, ultrasound

Introduction

To determine progress towards the Sustainable Developmental Goal (SDG) 3.2 “by 2030, to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age”, standardized data collection is critical 1– 3. Without a universally accepted definition to distinguish fetal death from miscarriage (spontaneous abortion) versus stillbirth 4, 5 ( Supplementary File 1) and the wide variation in standard of care available for live born extreme preterm births (exPTB), individual patient care and assessment of SDG progress are affected 6. Miscarriage remains an awkward condition to define due to variability between and even within countries particularly in relation to laws surrounding termination of pregnancy 7. There are obvious legal, religious and cultural sensitivities to pregnancy termination which may inhibit large organizations from specifying an upper limit to define miscarriage 8. The International Classification of Diseases, provides a graded definition of miscarriage (pregnancy loss before 22 completed weeks gestation); and stillbirth (expulsion of a fetus with no signs of life) classified as early fetal death (of a fetus weighing 500 g or more, or aged 22 weeks or more, or with a body length of 25 cm or more); late fetal death (of a fetus of 1000 g or more, or aged 28 weeks or more, or with a body length of 35 cm or more) 9. These definitions overlap. For example, is a stillborn 1000 g fetus with accurately determined gestation born at 27 +2 weeks +days, a late fetal death because of the birth weight or an early fetal death because of the gestation? For organizations that utilize the WHO definition of stillbirth recommended for global comparison i.e.: “a baby born with no signs of life at or after 28 weeks gestation” 10 confusion arises with live newborns before 28 weeks. It is difficult to explain to health care workers that stillbirth starts at 28 weeks but live birth can start at <28 weeks.

On the Thailand-Myanmar border at Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU), the WHO definition of stillbirth based upon reaching 28 weeks gestation has been used for the past 32 years ( Supplementary File 1). Based on this definition there has been a significant decline in stillbirth (28 to 14 per 1,000 live births) and neonatal mortality (49 to 11 per 1,000 livebirths) from 1993–1996 to 2008–2011 11, 12. Miscarriage rates have been stable over time at 10% (2257/23 118) from 1994 to 2013 13. The outcomes of pregnancies of 28 weeks or more gestation in this area have been published previously and are not the focus of this analysis 12, 14, 15.

One of the most significant factors in this border region has been the 3 decades long struggle with recurring loss of antimalarials to treat patients with multi-drug resistant P. falciparum malaria 16. The Thailand-Myanmar border was one of the first places in the world to introduce artemisinin-based combination therapy for treatment of malaria in the general population 17. The artemisinin derivatives were also used initially for treatment of malaria in the 2 nd and 3 rd trimesters of pregnancy or to save the life of the mother with severe malaria in any trimester 18. This class of drug distinguished itself in pregnancy as it was first reported by Chinese scientists to cause fetal resorption (or early miscarriage) 19 so it was important to be able to determine gestational age during pregnancy and to have a clear definition of trimester and miscarriage. Quinine remained the WHO recommended drug for women in the first trimester of pregnancy and systematic data collection by local health workers has built an evidence base that has made a significant contribution to global knowledge about antimalarial drug use in pregnancy particularly in the first trimester 13, 20.

In the 1990’s at SMRU, gestational age during pregnancy was estimated from fundal height by a formula developed for the study population 21, 22 or by last menstrual period (LMP), and from late 2001 by ultrasound 23. In 1995 the only tools available in the field were pregnancy tests, symphysis fundal height measurement (SFH), pinnard and at best (late 1990’s) a small hand-held Doppler to detect fetal heart beat. SFH measurements were routinely carried out at antenatal care and quality control measurement exercises were conducted because it was so heavily relied upon. SFH was examined at every visit until the fundus of the uterus could be felt for the first time and thereafter approximately every 2–4 weeks unless more frequent repeated measures were indicated. In these circumstances and in the absence of bleeding or fetal movements, detection of loss of fetal viability was identified late. When ultrasound was introduced in the area, a first trimester or first ANC visit scan was followed up by a repeat scan initially at 18 weeks and later shifted to 22 weeks. Gestational age of a non-viable fetus could be more readily obtained by ultrasound but for SMRU data to be consistent with the former data, the end of gestation of pregnancy has remained constant, as the date of expulsion of the products of conception.

At the same time, work has been standardized for local health workers by use of obstetric guidelines 24. In the guidelines the working definition of miscarriage is outcome of pregnancy before 28 weeks, while births (stillbirth and live birth) commence from 28 weeks, as does reporting of neonatal deaths. This definition has remained unchanged with the establishment of a special care baby unit in this resource limited setting where assisted ventilation of newborns is not available (i.e birth before 28 weeks is not viable) 12.

The objective of this study is to bring clarity to the nature of the products of conception that are expulsed in the 22 to <28 weeks gestational age window in a low resource setting, highlighting operational issues and the role of ultrasound 9.

Methods

Setting

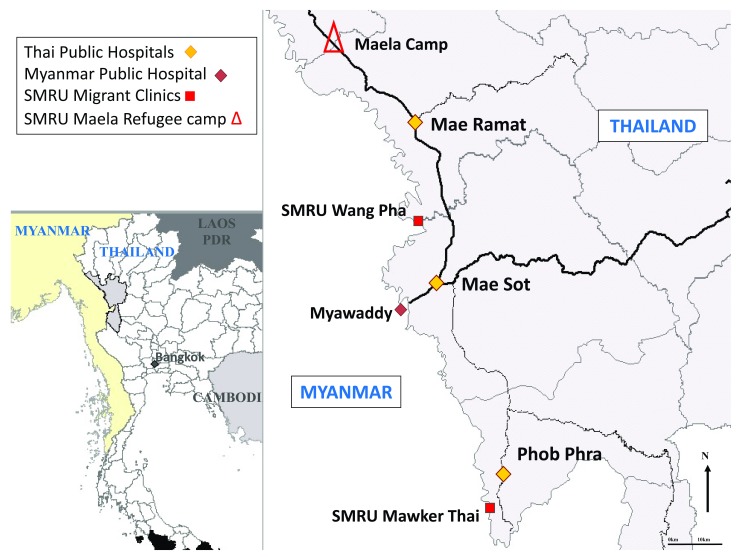

SMRU is an operational field-based research unit uniquely combining humanitarian work with research of direct relevance to the local population. It is a limited-resource setting working with marginalized populations on the western border of Thailand in Tak Province. In this area, there are an estimated 140,000 refugees and 200,000 migrants from Myanmar. There have been decades of neglect of the health system in Myanmar and the government is currently trying to address this. The refugee situation on the border of Thailand and Myanmar is amongst the most protracted in Asia but it has set a scenario of how health, particularly among pregnant women and obstetric emergencies of Myanmar people are managed. Due to conflict in Eastern Kayin state, refugees obtained surgical care in Thailand hospitals via a system of referral from Community-Based- and Non-Government Organizations. Health care for migrant pregnant women was established in 1998 by SMRU as there were minimal services available for them ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of the border area.

Location of SMRU clinics where pregnant women can attend for antenatal care and childbirth.

At SMRU, place and attendance at birth has shifted from 75% occurring at home with traditional birth attendants with no formal training in 1986, to more than 80% of births occurring in health facilities with skilled attendants in 2015 15. SMRU is staffed predominantly by locally trained workers for antenatal care and ultrasound 23, child birth 15, 24 and emergencies in adults and neonates 12. Local medics, midwives and nurses do the majority of the clinical work and expatriate doctors assist local staff with 24-hour back up. Ultrasound quality has been measured previously in this setting 23 and the eight sonographers undergo a small quality control every 6 months by a clinician (5 scans, blinded to gestation, to check for image quality and intra and inter-observer error) 24. Over 3,000 women register at SMRU antenatal clinics annually and these were well established before birth services were offered. The first birthing unit was opened at Shoklo refugee camp in 1986, with border skirmishes and closure of Shoklo, this was relocated to Maela Refugee camp in 1995, and two more units for marginalized migrant workers were opened in Wang Pha in Dec-2007 and in Maw Ker Thai in April 2010 ( Figure 1).

The seven signal functions for Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care, including parenteral administration of an oxytocic, antibiotics and anticonvulsants, removal of retained products of conception, assisted vaginal birth including breech birth, resuscitation of the newborn using a bag and mask for infants ≥ 28 weeks gestation, and screened blood transfusions, are provided by local staff. A description of the special care baby unit for neonates has been detailed by Turner et al. 12, but there is no capacity for intubation and assisted ventilation and prohibitive costs limit newborn referrals. Aminophylline is used in place of caffeine for apneas, again due to costs. Local protocols guide care and are regularly updated with trainings of the local staff. The protocol for preterm labour recommends dexamethasone (betamethasone is not available) and nifedipine at a gestation of at least 28 weeks. If extreme PTB (exPTB) occurs (<28 weeks) infants are provided with palliative care. Parents are involved and counseled in the process 12. No resuscitative efforts are offered to live born infants of 22 to <28 weeks gestation as no further sophisticated care i.e. intubation, incubators, surfactant, parenteral nutrition etc. is available 25. Women who need caesarean section or who have complex medical conditions are transferred by car to Thai hospitals (45 to 90 minutes away).

Pregnancy ultrasound and fetal viability

Ultrasound scans have been performed by local health workers using various scanners, including Toshiba Powervision 7000, Dynamic Imaging (since 2001), Fukuda Denshi UF 4100, and General Electric Voluson-1. Since 2001 all women have been offered two scans: once at booking to determine viability, number of fetus and gestation, regardless of how far progressed the pregnancy is, but preferably between 8 and 14 weeks; and again at 22 (18–24) weeks to reassess viability, measure fetal biometry and major abnormalities and determine placental location 23. Ultrasound can be repeated at any time as required. For example, if a woman reported absence of fetal movement, or bleeding, or the fundal height did not increase, an ultrasound could be done to determine viability. Measurement of the fetus size at each scan was encouraged. Loss of fetal heart beat could also be an incidental finding when the woman attended for her second scan. Loss of viability with ultrasound could be confirmed by presence of a fetus and absent fetal heartbeat. In some cases, ultrasound confirmed pregnancies persisting to 22 weeks gestation, but a fetus was never observed, e.g. anovulatory gestation or non-classic gestational trophoblastic disease.

In this setting SFH measurement has been important to determine whether a woman was in the first or second trimester which made the difference between being able to use quinine or artesunate to treat uncomplicated malaria. At antenatal care, pregnant women had abdominal palpation at each visit until the SFH was first palpable and measurable above the symphysis, then SFH was checked monthly up to 32 weeks and weekly from 36 weeks gestation. In case of doubt, urine (sometimes serum) pregnancy testing was available. It was and still is common to have the SFH measured multiple times in a single pregnancy 21, 26. Before ultrasound availability, loss of fetal viability could be confirmed by SFH measurements, which were increasing and then levelled off, or decreased with unexpected SFH results being confirmed by a clinician), complaints of loss of fetal movement or never feeling movement, bleeding episodes or expulsion of products. Quality control exercises of SFH involved comparing 20 women per month between SFH measurers – a difference of > 1cm was considered inacceptable and corrections of the firmness of applying the tape measure, correctly placing the end of the tape measure on the upper border of the symphysis pubis and identifying the fundus, were made during these sessions.

Management of fetal loss diverged from high income settings. Before misoprostol was available, induction of pregnancies with confirmed fetal loss was difficult and if there was no vaginal bleeding and the cervix was not open a conservative management style was adopted. Induction with syntocinon, the only available agent for many years, was frequently a prolonged and unsuccessful process. In this low resource context, only surgical emergencies were referred to tertiary hospitals, so non-viable pregnancy loss, with no imminent danger signs did not qualify for referral.

Data extraction and data definitions

All birth records at SMRU are computer based and paper-based records are archived at SMRU head office in Mae Sot. The original paper records initially matched data collection used by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in humanitarian settings. In 1998 computer based registration commenced with adjustments to the MSF form, in late 2001 ultrasound commenced requiring further amendments, and in late 2007 all data was captured in real time in an application developed by Technology Sans Frontières (TSF) with data limitations set to alert users to inaccurate entry. Verification of paper and computer based data has taken place over decades to a computer based record system.

All pregnancy records from 1995 until 2015 in the window period from 22 to <28 weeks gestation were selected and reviewed case by case by for the present study. The starting point of 1995 was selected, since the first local guideline for obstetrics was introduced at this time.

For each record the following evaluation was conducted using a step-wise query process:

a) Was there evidence of in utero fetal demise (no FHB) before 22 weeks? If yes, could the gestation of loss be estimated? For example, was fetal anthropometry measured by ultrasound when absence of fetal heart beat was confirmed; or did the SFH measurements stall or decrease (and at how many centimeters) before fetal heart beat could be heard or fetal movements felt, or did the mother report that she never felt fetal movements? Was there evidence that there was never a fetus i.e. that the pregnancy was never viable? Did ultrasound measure only annovulatory pregnancy (blighted ovum)?

b) Was there evidence of in utero fetal viability at 22 to <28 weeks gestation (FHB by ultrasound, hand held Doppler or Pinnard)? If yes, what was the estimated gestation at loss of viability and were there any signs of life (clinic births-heart beat by auscultation and home births-respiratory effort/movement) at birth?

c) If the outcome was a live birth, what was the neonatal outcome?

Records with evidence of in utero fetal demise before 22 weeks but expulsion between 22 to <28 weeks were classified as miscarriage (late expulsion). Pregnancies with evidence of fetal viability at ≥22 weeks that were expulsed between 22 to <28 weeks were classified as exPTB (live or stillborn). Neonatal mortality was defined as death in the first 28 days of a live born neonate of 22 to <28 weeks gestation. Gestational trophoblastic disease and termination of pregnancy were excluded. Congenital abnormalities were coded using the ICD-10 criteria 9.

Statistical analysis

Gestation was reported by week, for example 22 weeks included women from 22 +0 to 22 +6 weeks, (i.e 22 weeks plus 6 days) of pregnancy. Continuous normally distributed data, such as gestation and birth weight, were described using the mean, and standard deviation (SD) and compared with the Student’s t-test. Only the first born twin birth weight was retrieved from the electronic files. Non-parametric data, such as gravidity, were described using median and 25 th-75 th percentiles and compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Proportions were compared using the Chi-squared test. To assess the role of ultrasound in the final classification as exPTB rather than miscarriage between 22 to <28 weeks gestation, univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to determine the association between ultrasound use and outcome, adjusted for first ANC attendance in first trimester and delivering with a skilled attendant (confounders identified a priori). Data was analysed using SPSS version 20 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata version 13 (StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for retrospective analysis of pregnancy records was given by the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OXTREC 28–09) and after discussion with the local Community Advisory Board (TCAB-4/1/2015)

Results

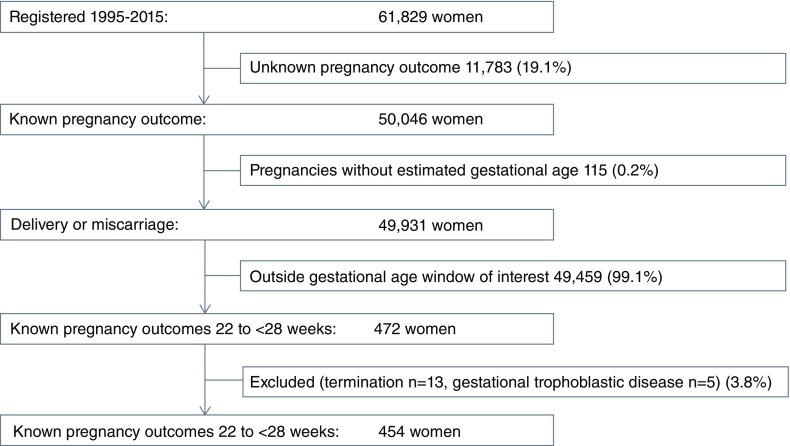

Between 1995 and 2015, 80.9% (50,046/61,829) of women registered to antenatal care had a known pregnancy outcome and were included in the present study. Only a small proportion, 0.2% (115/50,046), of these pregnancies could not be assigned a reliable gestational age ( Figure 2). The proportion of all pregnancy outcomes within the gestational window of 22 to <28 weeks was small: 0.9% (472/49,931) and most of these had an obstetric ultrasound scan and dating: 73.1% (345/472).

Figure 2. Study flow.

Selection of women in the cohort of 22 to < 28 weeks gestation.

There were 3.8% (18/372) excluded from analysis: termination of pregnancy involved 13 cases including: six ultrasound confirmed major fetal abnormality (five anencephalic, one holoprosencephaly), two life-threatening maternal conditions both with uncontrollable severe pre-eclampsia, and five self-induced (one of whom was recently widowed); and five gestational trophoblastic disease. The demographic characteristics of the remaining 454 pregnancy outcomes are summarized in Table 1. The majority of these pregnancies were dated by ultrasound: 72.5% (329/454). The numbers and proportions of pregnancy outcome for each gestational age week from 22 to <28 are shown in Table 2. There were 6.2% (28/454) twin pregnancies.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics of 454 women with pregnancy outcome 22 to <28 weeks gestation.

*Missing data: weight first ANC, weight less than 40 kg at first ANC n=3; BMI and BMI category n=158; Anemia at first ANC visit n=24. Abbreviation: ANC, antenatal clinic.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean [±SD], [min-max] | 28 [±8] [13–48] |

| Gravidity, median {25 th-75 th percentile}, [min-max] | 3 {2–5},[1–15] |

| Parity, median {25 th-75 th percentile}, [min-max] | 2 {0–4},[0–11] |

| Primigravida, % (n) | 24.4 (111/454) |

| Grandmultipara (more than 4 births), % (n) | 16.5 (75/454) |

| Weight first ANC, kg, mean [±SD], [min-max] * | 48 [±8] [31–81] |

| Weight less than 40 kg first ANC, n (%) | 8.9 (40/451) |

| BMI, kg/m 2 at first ANC *, mean [±SD] [min-max]; | 21.5 [±3.3], [13.6–34.2] |

| Underweight (<18.5), % (n) | 14.2 (42) |

| Normal weight (18.5 to < 23), % (n) | 61.7 (182) |

| Over weight (23 to <27.5), % (n) | 18.0 (53) |

| Obese (≥ 27.5), % (n) | 6.1 (18) |

| Number of ANC visits,

median{25 th-75 th percentile}, [min-max] |

6 {3-11}, [1-22] |

| A total of 4 or more ANC visits, % (n) | 58.4 (265/454) |

| Anemia at first ANC, % (n) * | 12.3 (53/430) |

| First ANC visit in trimester one (less than 14 weeks), % (n) | 55.5 (252/454) |

Table 2. Numbers and proportions of pregnancy outcomes by gestational age week 22 to <28 weeks.

| Weeks gestation at pregnancy outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | |

| N | 454 | 71 | 78 | 80 | 60 | 86 | 79 |

| Miscarriage | 197

(43.6) |

55

(77.5) |

47

(60.3) |

41

(51.3) |

20

(33.3) |

15

(17.4) |

19

(24.1) |

| Extreme PTB | 257

(56.4) |

16

(22.5) |

31

(39.7) |

39

(48.8) |

40

(66.7) |

71

(82.6) |

60

(75.9) |

| Twins a | 28

(61.8) |

1

(1.4) |

5

(6.4) |

2

(2.5) |

7

(11.7) |

6

(7.0) |

7

(8.9) |

| Extreme PTB | |||||||

| Missing data on live

and still birth |

5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Stillbirth | 120/252

(47.6) |

12

(75.0) |

22

(71.0) |

18

(47.4) |

18

(47.4) |

33

(46.1) |

17

(28.8) |

| Live birth | 132/252

(52.4) |

4

(25.0) |

9

(29.0) |

20

(52.6) |

20

(52.6) |

37

(52.9) |

42

(71.2) |

| Survival of Newborns | |||||||

| Missing data NND | 1 a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| NND day 1 | 87/131

(66.9) |

4

(100.0) |

9

c

(100.0) |

17

(85.0) |

18

(90.0) |

22

(59.5) |

18

(42.9) |

| NND day 3 | 114/131

(87.0) |

4

(100.0) |

9

c

(100.0) |

19

(95.0) |

19

(95.0) |

31

(83.8) |

33

(78.6) |

| NND day 28 | 129/131

(98.5) |

4

(100.0) |

9

(100.0) |

20

(100.0) |

20

(100.0) |

37

(100.0) |

39

(95.2) |

| Alive > 1 month | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 d |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated; Abbreviations: n.a, NND neonatal death; PTB preterm birth

aMost twins pregnancies were extreme PTB except for 2 which were miscarriage at 23 weeks

bBorn alive and probably died but data not available in the record

cnot sure exact days NND (only 700g and born at home, brought to clinic)

dOne died at day 33; one was still alive at 40 months of age

Miscarriage

Of the 454 pregnancy outcomes from 22 to <28 weeks gestation 197 (43.5%) were miscarriage (loss of viability before 22 weeks) two of which were twin gestations (23 weeks) ( Table 2). More than half of 197 miscarriages occurred at 22 and 23 weeks gestation 27.9% (55) and 23.9% (47); with 24, 25, 26, and 27 weeks accounting for 20.8% (41), 10.2% (20), 7.6% (15) and 9.6% (19), respectively.

Loss of viability was not possible to determine for 11 records (nine indicated spontaneous miscarriage and two records could not be located) leaving 186 records. Evidence of fetal demise (absence of fetal heart beat) also known as fetal death in utero, occurred in 60.2% (112/186), with most of these determined by ultrasound ( Table 3). The proportion with stalling or decreases in SFH was higher before ultrasound was introduced ( Table 3). Annovulatory pregnancy (blighted ovum) was also a reason for expulsion of products of pregnancy from 22 to < 28 weeks of pregnancy in this setting: 16.8% (19/113) when ultrasound was available ( Table 3). In the 112 cases with fetal death in utero the estimated time from non-viability to expulsion was a median of 7 +1 [IQR 4 +5 to 11 +0] weeks +days. ( Table 3), and not significantly different pre and post ultrasound: 6 +3 (n=24) vs 7 +4 weeks +days (n=88), p=0.084.

Table 3. Reason for late miscarriage (expulsion 22 to <28 weeks gestation) and the estimated gestational age of loss of viability (median [min-max] in weeks).

| Before ultrasound (n=73) | Ultrasound (n=113) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | N (%) | EGA of loss of viability | N (%) | EGA at loss of viability |

| Fetal death in utero | 24 (32.9) | 16 +6 [11 +1-21 +6] | 88 (77.9) | 16 +3 [7 +2-21 +6] |

| SFH stalled or decreased | 41 (56.2) | 16 +0 [8 +0-21 +0] | 6 (5.3) | 16 +0 [10 +0-17 +2] |

| Annovulatory | 8 (10.9) | 8 +0 [ 7+0-8 +0] | 19 (16.8) | 8 +0 [7 +0-12 +0] |

Extreme preterm birth (22 to <28 weeks)

There were 56.4% (257/454) of women with an exPTB of which 89.9% (231/257) were singletons and 10.1% (26/257) were twins ( Table 2). The gender of the infant was missing for 30.0% (77/257) cases, with the remainder including 56.1% (101/180) males and 43.9% (79/180) females.

Amongst the 257 pregnancies ending in exPTB, 1.9% (5/257) had missing data on whether the infant was still- or live born ( Table 2), and for the remaining cases, 47.6% (120/252) were recorded as stillbirths (including first born twin), and 52.4% (132/252) were born alive. Most women birthed vaginally, 98.0% (253/257), with 66.5% (171/257) in SMRU clinic. There were 1.6% (4/252) delivered by caesarean sections. These four cases were in singleton pregnancies, three at 27 weeks and one at 26 weeks, three of whom had placental pathologies (two placenta praevia and one placental abruption) and one with preterm labour and transverse presentation. These four births all ended in stillbirth with a birth weight available for one case (900g).

The birth weight measured in singletons was not available for 42.0% (108/257) of neonates. For the 75 homebirths this is not surprising. Birth weight of 17 congenitally abnormal infants was excluded from analysis. Birth weight in live born, normal singletons in the period before ultrasound (n=18) and when ultrasound was available (n=67) was similar: mean±SD (range): 817±253 (350–1300) and 875±231 (220–1500) g (p=0.380). The mean±SD (min-max) birth weight was higher in live born (n=85) than stillborn (n=27) normal singletons infants: 863±235 [220–1500] and 652±208 [400–1320] g, (p<0.001). Mean birth weights for singletons and first-born twins were summarized for each gestational age week after excluding birth weight of those with congenital abnormality ( Supplementary File 2).

Congenital abnormality involved 10.6% (24/227, 30 missing) of exPTB and half of these congenital abnormality cases 50.0% (12/24) were stillborn ( Table 4).

Table 4. Congenital abnormalities, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities in 24 extreme preterm newborns, according to ICD-10 coding.

amultiple abnormalities, enalapril exposure; **also undiagnosed heart murmur.

| System | Description | ICD-10

code |

n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central nervous

system |

Anencephaly | Q00.0 | 2 |

| Encephalocele a | Q01 | 1 | |

| Microcephaly | Q02 | 1 | |

| Hydrocephalus | Q03 | 2 | |

| Brain abnormality, unspecified | Q04.9 | 1 | |

| Spina bifida | Q05 | 1 | |

| Cardiovascular | Malformation of cardiac

chambers, not specified |

Q20.9 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal | Oesophageal atresia | Q39 | 2 |

| Urinary system | Outflow obstruction | Q64.7 | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal | Talipes (home birth, few details) | Q66.4 | 1 |

| Phocomelia | Q72.2 | 2 | |

| Other | Fetal hydrops Not specified | P56 | 2 |

| Massive cystic hygroma | Q87.8 | 3 | |

| Severe amniotic bands ** | Q79.8 | 1 | |

| Twin to twin transfusion

syndrome |

Q89.9 | 1 | |

| (suspected) Trisomy-21 | Q90 | 1 |

aEncephalocele and other abnormalities: arthryogyrophosis, micropthalmia – enalapril exposure

Newborn survival

Of the 132 liveborn exPTB, the fate of one neonate was unknown at one month. Of the remaining neonates 98.5% (128/131) had a neonatal death and 1.5% (2/131) survived the first 28 days. The median [IQR, range] age of neonatal deaths was 1 [1–2, 1–28] day, with 87.0% (114/131) by day 3 ( Table 2). One newborn died at day 33 and the remaining child survived and was still alive when last seen at 40 months of age, with a normal neurodevelopment. The surviving female child was born at 27 +5 weeks, and two ultrasounds, including an early scan at 8 weeks and a later scan at 18 weeks, assured the gestation. The mother was a 32-year-old refugee with a gravidity of two and parity of one, with no history of PTB, who went into spontaneous labour and received a single dose of nifedipine and dexamethasone less than one hour before delivery. Delivery was supervised by skilled birth attendants and after a normal vaginal birth of a 890g baby, the Apgar scores were six and seven, at one and five minutes, with no resuscitation necessary. The neonate was provided with supportive care (with oxygen delivered by nasal prongs; temperature control, phototherapy, breast milk) because that was all that was available, and discharged home after ten weeks at 1061g.

The role of ultrasound

Use of ultrasound was associated with an increased adjusted odd ratio (AOR) of being classified as exPTB rather than miscarriage: AOR 2.09 (95%CI 1.31–3.34, p=0.002); while attending in the first trimester for the first antenatal visit and delivery at SMRU clinics were not associated: AOR 1.29 (95%CI 0.87–1.91, p=0.212), and AOR 0.93 (95%CI 0.61–1.45, p=0.802), respectively ( Table 5).

Table 5. The association between use of ultrasound and outcome classification as extreme PTB or miscarriage between 22 to <28 weeks (n=454).

Numbers are % (n), Missing data: Place of birth SMRU (22). *Ultrasound was not introduced at SMRU until late 2001. Abbreviation: ANC antenatal consultation, SBA skilled birth attendant.

| Extreme PTB

n=257 |

Miscarriage

n=197 |

Odds Ratio

(95% CI), P-value |

Adjusted odds

ratio (95% CI), p-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound * | Yes (all 2002–2015) | 62.9 (207/125) | 37.1 (122/329) | 2.55 (1.67-3.88),

p<0.001 |

2.04 (1.28-3.25),

p=0.003 |

| No (all 1995–2001) | 40.0 (50/329) | 60.0 (75/125) | |||

| Early ANC

attendance |

1st trimester | 53.0 (133/251) | 47.0 (118/251) | 1.39 (0.96-2.03),

p=0.084 |

1.30 (0.88-1.93),

p=0.191 |

| 2 nd/3 rd trimester | 61.1 (124/203) | 38.9 (79/203) | |||

| Delivery at clinic

with SBA |

Clinic | 61.5 (177/287) | 38.5 (110/267) | 0.74 (0.50-1.12),

p=0.151 |

0.93 (0.61-1.44),

p=0.754 |

| Home | 54.5 (79/145) | 45.5 (66/145) |

Discussion

Cautious interpretation of this data is required given the limitations of this dataset because 19% of women who registered to antenatal care had no pregnancy outcome reported. In a recent Lancet report of Myanmar Demographic Health Surveillance in 2016, less than 30% of rural women in Myanmar delivered in recognized institutions 27. In the context of this post-conflict, cross border, low resource setting, the fact that 81% of outcomes were reported, with ultrasound available for nearly ¾, supports the use of the data to bring clarity to the nature of the products of conception expulsed in the 22 to <28 weeks gestational age window. As well the median number of six antenatal consultations ( Table 1) is high for pregnancies ending before 28 weeks gestation in a limited-resource setting.

The window of gestation from 22 to <28 weeks involved less than 1% of all pregnancy outcomes and 4 in 10 outcomes were miscarriage (i.e. non-viable before reaching 22 weeks). Ultrasound was associated with a 2 times higher odds of the outcome being classified as an exPTB rather than a miscarriage. This suggests that ultrasound adds clarity to the outcome of pregnancy in this 22 to <28 week window, mostly because it detects the presence/absence of a fetal heart beat or in this setting even the presence of annovulatory pregnancy – both of which are not easily identified with more limited tools (pregnancy test, SFH and pinnard/hand held Doppler). Under the WHO/ICD 10 definition these miscarriages could be (wrongly) defined as exPTB based on gestation alone, which would falsely inflate stillbirth rates 4 ( Supplementary File 1).

Amongst the outcomes classified as exPTB, nearly one-half were stillborn, 98.5% of the babies born alive were neonatal deaths of which two-thirds occurred on day one, and there was a high proportion (as expected) of congenital abnormalities. A high congenital abnormality rate is expected amongst this age group in a setting that does not actively screen for abnormalities 28. Two infants emerged from the neonatal period, one died at day 33 and one female of 27+5 weeks gestation survived infancy (end of the first year). Not only are the outcomes of pregnancies of 22 to <28 weeks gestation in this setting dismal, the proportion of pregnancies that are involved, relative to all pregnancies with a known outcome, is small (0.9%). It could be argued that if more than palliative care was offered to the newborns at SMRU, outcomes may have been different but with no means to provide additional support such as intubation, incubators, surfactant, parenteral nutrition etc, improvements would remain marginal. The high proportion of stillbirths (47.6% (120/252) contrasts with rates under 2% previously reported in this population in the 28 to <34 week’ gestation window 12. Stillbirth rates may be inflated using gestational age rather than birthweight cut-offs 29 and also because nearly all these infants were born vaginally, including breech births, whereas caesarean section may have been offered in HIC. These different proportions are important because they indicate that in low resource setting, the maximum benefits of interventions to prevent newborn death, is in the group of 28 weeks (and above) gestation 30. Overall, this data supports the WHO definition of 28 weeks to define birth (live birth and stillbirth) 31, and <28 weeks as a pragmatic definition of miscarriage 32

In low resource settings there are many reasons why women may have a late outcome (22 to <28 weeks gestation) of a miscarriage (non-viable before 22 weeks) ( Table 3). Coming in to the clinic for an induction when there is no pain or bleeding (no obvious problem that is felt by the woman herself) may be perceived as being of greater consequence than not being able to plant or harvest crops, or not being able to receive daily wages which the family depend upon. Information on fetal movement was rarely volunteered so there may be cultural reasons for apparent tolerance to loss of fetal viability such as desire for fetus papyraceus, which, surprisingly, is culturally fortunate 33.

Registration of births is incomplete in many LIC 34 and dating pregnancies reliably a particularly challenging issue 35. Some of the higher end birth weights may be due to inaccurate dating but meta-analysis 14 also suggests 1000g as a cut-off misses gestations in the exPTB window. On the Thailand-Myanmar border, SMRU has integrated basic ultrasound delivered by local sonographers to routine ANC and this has been accepted by women 36. Efforts have been directed towards having local staff skilled in routine gestational age scanning 23, standard care at antenatal clinics and at birth 15, and in newborn care 12. Record keeping has been based on the cut-off point of 28 weeks gestation for birth and miscarriage and while that has been a strength in directing human resources in the delivery room and in special care baby unit to viable neonates it has also resulted in weaker reporting of pregnancy outcomes from 22 to <28 weeks, which is an obvious limitation of this data set. Another limitation of the analysis is the 21 year period of the cohort. This could however be viewed differently as it puts into perspective the small group of pregnancies involved: approximately six live born exPTBs per year compared to >2,000 births of 28 weeks or more per year. While there have been changes over time including the introduction of a special care baby unit and ultrasound, there has been no change in the assisted ventilatory support of newborns, which is not available.

In a low resource setting the outcome of pregnancy between 22 to <28 weeks gestation involves <1% of all outcomes, a high proportion of miscarriage (late expulsion), with one-in-two of the exPTBs being stillborn and amongst livebirths, a neonatal mortality approaching 100%. The distinction between miscarriage and exPTB in this gestational window is improved by ultrasound but this is unlikely to result in improvement in survival due to significant resource constraints. The WHO cut-point to define stillbirth and miscarriage is pragmatic and useful in low resource settings in the scale-up towards reducing preventable newborn deaths as it allows a greater focus on newborns more likely to survive with a gestation of 28 weeks or more.

Data availability

Due to ethical and security considerations, the data that supports the findings in this study can be accessed only through the Data Access Committee at Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU). The data sharing policy can be found here: http://www.tropmedres.ac/data-sharing. The application form for datasets under the custodianship of MORU Tropical Network can be found in Supplementary File 3.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the staff of SMRU and pregnant women who came to the clinics at this difficult gestation, and we take this opportunity to thank them for their participation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust Thailand Major Overseas Programme 2015-2020 [106698].

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 3; referees: 2 approved, 2 approved with reservations]

Definitions of miscarriage and stillbirth: Internationally and at Shoklo Malaria Research Unit.

Mean birth weight of extreme preterm births by gestational age between 22 to <28 weeks.

Application form for data

References

- 1. Goldenberg RL, Gravett MG, Iams J, et al. : The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):113–118. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer MS, Papageorghiou A, Culhane J, et al. : Challenges in defining and classifying the preterm birth syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):108–112. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quinn JA, Munoz FM, Gonik B, et al. : Preterm birth: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunisation safety data. Vaccine. 2016;34(49):6047–6056. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tavares Da Silva F, Gonik B, McMillan M, et al. : Stillbirth: Case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2016;34(49):6057–6068. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rouse CE, Eckert LO, Babarinsa I, et al. : Spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2017;35(48 Pt A):6563–6574. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lumley J: Defining the problem: the epidemiology of preterm birth. BJOG. 2003;110 Suppl 20:3–7. 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ganatra B, Guest P, Berer M: Expanding access to medical abortion: challenges and opportunities. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;22(44 Suppl 1):1–3. 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)43793-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO: Reproductive health indicators : guidelines for their generation, interpretation and analysis for global monitoring. In: World Health Organization, Geneva;2006. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th revision, edition 2010. In: NLM classification: WB 15 Geneva: WHO;2010. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. : Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):587–603. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luxemburger C, McGready R, Kham A, et al. : Effects of malaria during pregnancy on infant mortality in an area of low malaria transmission. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(5):459–465. 10.1093/aje/154.5.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Turner C, Carrara V, Aye Mya Thein N, et al. : Neonatal intensive care in a Karen refugee camp: a 4 year descriptive study. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72721. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moore KA, Simpson JA, Paw MK, et al. : Safety of artemisinins in first trimester of prospectively followed pregnancies: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(5):576–583. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00547-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore KA, Simpson JA, Thomas KH, et al. : Estimating Gestational Age in Late Presenters to Antenatal Care in a Resource-Limited Setting on the Thai-Myanmar Border. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131025. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. White AL, Min TH, Gross MM, et al. : Accelerated Training of Skilled Birth Attendants in a Marginalized Population on the Thai-Myanmar Border: A Multiple Methods Program Evaluation. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164363. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carrara VI, Zwang J, Ashley EA, et al. : Changes in the treatment responses to artesunate-mefloquine on the northwestern border of Thailand during 13 years of continuous deployment. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4551. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nosten F, van Vugt M, Price R, et al. : Effects of artesunate-mefloquine combination on incidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and mefloquine resistance in western Thailand: a prospective study. Lancet. 2000;356(9226):297–302. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02505-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McGready R, Cho T, Cho JJ, et al. : Artemisinin derivatives in the treatment of falciparum malaria in pregnancy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92(4):430–433. 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)91081-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li ZL: [Teratogenicity of sodium artesunate]. Zhong Yao Tong Bao. 1988;13(4):42–44, 63–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dellicour S, Sevene E, McGready R: First-trimester artemisinin derivatives and quinine treatments and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in Africa and Asia: A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5):e1002290. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. White LJ, Lee SJ, Stepniewska K, et al. : Estimation of gestational age from fundal height: a solution for resource-poor settings. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(68):503–510. 10.1098/rsif.2011.0376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nosten F, McGready R, Simpson JA, et al. : Effects of Plasmodium vivax malaria in pregnancy. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):546–549. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09247-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rijken MJ, Lee SJ, Boel ME, et al. : Obstetric ultrasound scanning by local health workers in a refugee camp on the Thai-Burmese border. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(4):395–403. 10.1002/uog.7350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoogenboom G, Thwin MM, Velink K, et al. : Quality of intrapartum care by skilled birth attendants in a refugee clinic on the Thai-Myanmar border: a survey using WHO Safe Motherhood Needs Assessment. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:17. 10.1186/s12884-015-0444-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Janet S, Carrara VI, Simpson JA, et al. : Early neonatal mortality and neurological outcomes of neonatal resuscitation in a resource-limited setting on the Thailand-Myanmar border: A descriptive study. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190419. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. White LJ, Lee SJ, Stepniewska K, et al. : Correction to 'Estimation of gestational age from fundal height: a solution for resource-poor settings'. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(113): 20150978. 10.1098/rsif.2015.0978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han SM, Rahman MM, Rahman MS, et al. : Progress towards universal health coverage in Myanmar: a national and subnational assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(9):e989–e997. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30318-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Katorza E, Achiron R: Early pregnancy scanning for fetal anomalies--the new standard? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(1):199–216. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182446ae9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. : National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(2):e98–e108. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gülmezoglu AM, Lawrie TA, Hezelgrave N, et al. : Interventions to Reduce Maternal and Newborn Morbidity and Mortality. In: Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health: Disease Control Priorities. Third Edition: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Edited by Black RE, Laxminarayan R, Temmerman M, Walker N, Washington (DC);2016;2:115–136. 10.1596/978-1-4648-0348-2_ch7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frøen JF, Cacciatore J, McClure EM, et al. : Stillbirths: why they matter. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1353–1366. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62232-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joseph KS, Liu S, Rouleau J, et al. : Influence of definition based versus pragmatic birth registration on international comparisons of perinatal and infant mortality: population based retrospective study. BMJ. 2012;344:e746. 10.1136/bmj.e746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McGready R: Meet my uncle. Lancet. 1999;353(9150):414. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74998-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frøen JF, Myhre SL, Frost MJ, et al. : eRegistries: Electronic registries for maternal and child health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:11. 10.1186/s12884-016-0801-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hofmeyr GJ, Haws RA, Bergström S, et al. : Obstetric care in low-resource settings: what, who, and how to overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107 Suppl 1:S21–44, S44–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rijken MJ, Gilder ME, Thwin MM, et al. : Refugee and migrant women's views of antenatal ultrasound on the Thai Burmese border: a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]