Abstract

Anthropogenic activities near urban rivers may have significantly increased the acquisition and dissemination of antibiotic resistance. In this study, we investigated the prevalence of colistin resistant strains in the Funan River in Chengdu, China. A total of 18 mcr-1-positive isolates (17 Escherichia coli and 1 Enterobacter cloacae) and 6 mcr-3-positive isolates (2 Aeromonas veronii and 4 Aeromonas hydrophila) were detected, while mcr-2, mcr-4 and mcr-5 genes were not detected in any isolates. To further explore the overall antibiotic resistance in the Funan River, water samples were assayed for the presence of 15 antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and class 1 integrons gene (intI1). Nine genes, sul1, sul2, intI1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaCTX-M, tetM, ermB, qnrS, and aph(3′)-IIIa were found at high frequencies (70–100%) of the water samples. It is worth noting that mcr-1, blaKPC, blaNDM and vanA genes were also found in water samples, the genes that have been rarely reported in natural river systems. The absolute abundance of selected antibiotic resistance genes [sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, ermB, blaCTX-M, mcr-1, and tetM] ranged from 0 to 6.0 (log10 GC/mL) in water samples, as determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and ermB genes exhibited the highest absolute abundances, with 5.8, 5.8, and 6.0 log10 GC/mL, respectively. The absolute abundances of six antibiotic resistance genes were highest near a residential sewage outlet. The findings indicated that the discharge of resident sewage might contribute to the dissemination of antibiotic resistant genes in this urban river. The observed high levels of these genes reflect the serious degree of antibiotic resistant pollution in the Funan River, which might present a threat to public health.

Keywords: colistin, antibiotic resistance, mcr-1, mcr-3, urban river, quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Introduction

Multi-drug resistant (MDR) Gram-negative pathogens are resistant to almost all antibiotics, including cephalosporins, quinolones, aminoglycosides and carbapenems, making treatment difficult. Colistin is considered the last line of defense against MDR Gram-negative pathogens, playing an important role in the treatment of severe bacterial infections (Zavascki et al., 2007). Unfortunately, the recent emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance genes in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae presents a serious new threat to human health. The plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1 was first discovered Liu et al. (2016). Soon afterward, another mobile phosphoethanolamine transferase gene, termed mcr-2, was discovered in porcine and bovine Escherichia coli isolates in Belgium (Xavier et al., 2016). Recently, Yin et al. (2017) discovered a novel mcr subtype, mcr-3, encoded on an IncI2 plasmid in an E. coli isolated from a pig in China. The mcr-4 and mcr-5 genes were detected in Europe almost simultaneously (Borowiak et al., 2017; Carattoli et al., 2017). Although there have been numerous reports of colistin resistance genes in animals and humans, fewer studies have focused on mcr-bearing isolates from aquatic environments.

Due to the continual release of antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) into the environment from hospitals, livestock facilities, and sewage treatment plants (STP), antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) are regarded as environmental contaminants (Pruden et al., 2006; Zurfluh et al., 2017). The occurrence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic and zoonotic bacteria pose a potential threat to human health (Rosenberg Goldstein et al., 2012; Neyra et al., 2014). Moreover, an increasing number of bacteria are resistant to multiple antibiotics, and are able to transfer their resistant determinants among different bacterial species and genera in aquatic environments (Akinbowale et al., 2006). Urban rivers may provide an ideal setting for the acquisition and dissemination of antibiotic resistance because they are frequently impacted by anthropogenic activities. Although antibiotic resistance is a major and developing public health concern, the surveillance of this phenomenon in urban rivers is remarkably limited.

The Funan River, a major urban river in Chengdu used for agricultural activities (e.g., irrigation and cultivation) as well as recreational activities (e.g., swimming and fishing), was used as the model in this study to analyze the magnitude of antibiotic resistance in urban rivers.

The objectives of this study were: (1) to determine the prevalence of colistin resistance strains in the Funan River; (2) to investigate the MDR phenotypes and genotypes of isolated colistin resistant strains; (3) to screen for resistance determinants, including sul1, sul2, blaCTX-M, blaV IM, blaKPC, blaNDM, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, vanA, mecA, ermB, ermF, tetM, aph(3′)-IIIa, and mcr-1, and the class 1 integron gene (intI1) in water samples from the Funan River.

Materials and Methods

Sampling of River Water

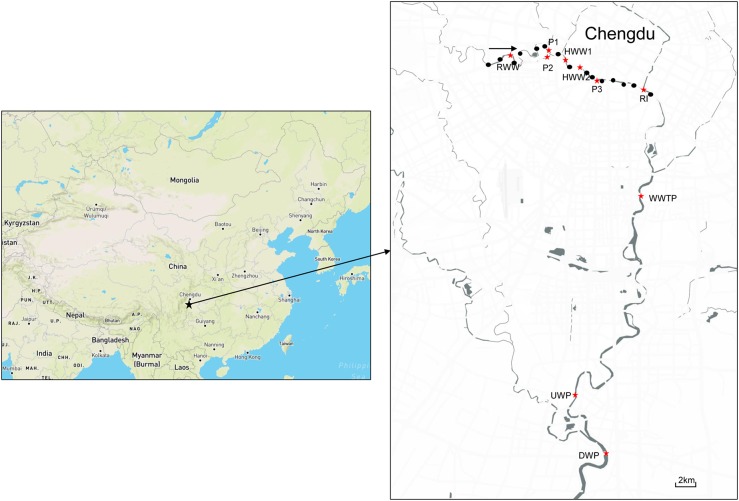

To investigate the prevalence of colistin resistant strains, 30 water samples (2 L) were collected from the Funan River near densely populated areas in September 2017. To further explore the antibiotic resistance of bacteria throughout the Funan River, 10 water samples (2 L) were collected from representative locations along the river (Figure 1). The representative locations included river intersections, streams near parks, and sewage outlets near residential areas, the hospital, and the municipal wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). The site near the residential sewage outlet is designated RWW and the sample near the municipal wastewater treatment plant is designated WWTP. Sites P1, P2, and P3 are close to various parks and HWW1 and HWW2 are close to the hospital sewage outlet. Site RI is located adjacent to the intersection of a tributary and the mainstream of the river. Sites UWP and DWP are upstream and downstream of Wetland Park, respectively. Water samples were collected from each site, immediately placed on ice, and transported to the laboratory within 4 h. The samples were then maintained at 4°C until investigation.

FIGURE 1.

Study area with sampling sites to explore the antibiotic resistance of bacteria throughout the Funan River. Black dots indicate partial sampling sites for the detection of colistin resistant bacteria and red stars indicate sampling sites for the ARG determination in river water. (RWW, Residential Wastewater; WWTP, Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant; P, Park; HWW, Hospital Wastewater; RI, River Intersection; UWP, Upstream of Wetland Park; DWP, Downstream of Wetland Park).

Bacterial Isolation

A total of 30 water samples were concentrated by vacuum filtration through 0.22 μm filter membranes. The membranes were washed and the collected material was suspended in 10 ml of sterile PBS. A volume of 1 ml thereof was added to 9 ml of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth with polymyxin B at a final concentration of 4 μg/mL. After incubation at 37°C overnight, 100 μl culture samples were streaked onto MacConkey agar plates. Fifty colonies were picked from each MacConkey agar plates and subsequently grown in BHI broth with 4 μg/mL polymyxin B for 18–24 h. Isolates were screened for the presence of mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4, and mcr-5 by PCR. Next, mcr-positive isolates were purified by subculturing. The mcr-positive isolates were identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the BD Phoenix-100 Automated Microbiology System (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, NV, United States).

Antimicrobial Resistance Testing and Detection of mcr-Positive Strains Genotype

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of colistin was determined by broth microdilution. The antimicrobial susceptibility was interpreted according to the guidelines of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) version 6.0 (EUCAST, 2017). Fourteen antimicrobial agents were tested: ampicillin (AMP, 10 μg), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC, 20/10 μg), cefotaxime (CTX, 30 μg), ceftriaxone (CRO, 30 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg), cefoxitin (FOX, 30 μg), imipenem (IPM, 10 μg), ertapenem (ETP, 10 μg), aztreonam (ATM, 30 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg), fosfomycin (FOS, 50 μg), tetracycline (TE, 30 μg), amikacin (AK, 30 μg) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT, 1.25/23.75 μg). Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by the agar disk diffusion method. Isolates were classified as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant using the breakpoints specified by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (CLSI, 2016). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as the quality control strain.

After DNA extraction using the TIANamp bacteria DNA kit (TIANGEN, China), the isolates were screened for the presence of 21 antibiotic resistance genes (blaKPC, blaOXA-48, blaNDM, blaV IM, blaIMP, blaSHV, blaTEM, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-9, fosA3, qnrB, qnrS, floR, oqxAB, sul1, sul2, tetM, tetA, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, rmtA, and rmtB) (Berendonk et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016), and the primers and PCR conditions used are listed in Table 1. Negative and positive controls for PCR of each gene were utilized.

Table 1.

Standard primer pairs used in this study.

| Target genes | Sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon size(bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mcr-1 | CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC | 350 | Liu et al., 2016 |

| CTTGGTCGGTCTGTA GGG | |||

| mcr-2 | TGGTACAGCCCCTTTATT | 1617 | Xavier et al., 2016 |

| GCTTGAGATTGGGTTATGA | |||

| mcr-3 | TTGGCACTGTATTTTGCATTT | 542 | Yin et al., 2017 |

| TTAACGAAATTGGCTGGAACA | |||

| mcr-4 | ATTGGGATAGTCGCCTTTTT | 487 | Carattoli et al., 2017 |

| TTACAGCCAGAATCATTATCA | |||

| mcr-5 | ATGCGGTTGTCTGCATTTATC | 1644 | Borowiak et al., 2017 |

| TCATTGTGGTTGTCCTTTTCTG | |||

| bla KPC | ATGTCACTGTATCGCCGTC | 902 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| TTACTGCCCGTTGACGCC | |||

| blaOXA-48 | TTGGTGGCATCGATTATCGG | 744 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| GAGCACTTCTTTTGTGATGGC | |||

| bla NDM | ATGGAATTGCCCAATATTATGCAC | 813 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| TCAGCGCAGCTTGTCGGC | |||

| blaV IM | TTTGGTCGCATATCGCAACG | 500 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| CCATTCAGCCAGATCGGCAT | |||

| bla IMP | GTTTATGTTCATACWTCG | 432 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| GGTTTAAYAAAACAACCAC | |||

| blaSHV | ATTTGTCGCTTCTTTACTCGC | 861 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| TTTATGGCGTTACCTTTGACC | |||

| bla TEM | ATGAGTATTCAACATTTCCGTG | 861 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| TTACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGAG | |||

| blaCTX-M | TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA | 759 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| CGATATCGTTGGTGGTGCCATA | |||

| bla CTX-M-1 | AAAAATCACTGCGCCAGTTC | 415 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| AGCTTATTCATCGCCACGTT | |||

| bla CTX-M-9 | CAAAGAGAGTGCAACGGATG | 205 | Zheng et al., 2015 |

| ATTGGAAAGCGTTCATCACC | |||

| fosA3 | GCGTCAAGCCTGGCATTT | 282 | Hou et al., 2012 |

| GCCGTCAGGGTCGAGAAA | |||

| qnrB | GATCGTGAAAGCCAGAAAGG | 469 | Wang et al., 2017 |

| ACGATGCCTGGTAGTTGTCC | |||

| qnrS | ACGACATTCGTCAACTGCAA | 540 | Wang et al., 2017 |

| TAAATTGGCACCCTGTAGGC | |||

| oqxAB | CCCTGGACCGCACATAAAG | 1140 | Wang et al., 2017 |

| AAAGAACAAGATTCACCGCAAC | |||

| sul1 | ATGGTGACGGTGTTCGGCATTCTG | 840 | Hur et al., 2011 |

| CTAGGCATGATCTAACCCTCGGTC | |||

| sul2 | GAATAAATCGCTCATCATTTTCGG | 810 | Hur et al., 2011 |

| CGAATTCTTGCGGTTTCTTTCAGC | |||

| tetM | AGTGGAGCGATTACAGAA | 158 | Adefisoye and Okoh, 2016 |

| CATATGTCCTGGCGTGTCTA | |||

| tetA | GCTACATCCTGCTTGCCTTC | 210 | Adefisoye and Okoh, 2016 |

| CATAGATCGCCGTGAAGAGG | |||

| aac(6′)-Ib-cr | TTGCGATGCTCTATGAGTGGCTA | 482 | Eftekhar and Seyedpour, 2015 |

| CTCGAATGCCTGGCGTGTTT | |||

| rmtA | CTAGCGTCCATCCTTTCCTC | 635 | Wang et al., 2017 |

| TTGCTTCCATGCCCTTGCC | |||

| rmtB | GCTTTCTGCGGGCGATGTAA | 173 | Wang et al., 2017 |

| ATGCAATGCCGCGCTCGTAT | |||

| floR | GTCGAGAAATCCCATGAGTTCA | 1645 | Cloeckaert et al., 2000 |

| CAGACAGGATACCGACATTCAC | |||

| intI1 | GGGTCAAGGATCTGGATTTCG | 484 | Mazel et al., 2000 |

| ACATGCGTGTAAATCATCGTCG | |||

| vanA | AATACTGTTTGGGGGTTGCTC | 734 | Kafil and Asgharzadeh, 2014 |

| TTTTTCCGGCTCGACTTCCT | |||

| mecA | TGGTATGTGGAAGTTAGATTGGGAT | 155 | Paterson et al., 2012 |

| CTAATCTCATATGTGTTCCTGTATTGGC | |||

| ermB | GATACCGTTTACGAAATTGG | 364 | Zhang et al., 2016 |

| GAATCGAGACTTGAGTGTGC | |||

| ermF | CGACACAGCTTTGGTTGAAC | 309 | Zhang et al., 2016 |

| GGACCTACCTCATAGACAAG | |||

| aph(3′)-IIIa | GCC GAT GTG GAT TGC GAA AA | 269 | Udo and Dashti, 2000 |

| GCT TGA TCC CCA GTA AGT CA |

Total DNA Extraction and Detection of ARGs

To further explore the extent of antibiotic resistance throughout the Funan River, water samples were collected from 10 locations (Figure 1). Total DNA was extracted using the Water DNA kit (OMEGA, United States) from the bacteria sample trapped by 0.22 μm pore filter (2 L samples). Standard PCR performed as listed in Table 1 was used to detect 15 ARGs (sul1, sul2, blaCTX-M, blaV IM, blaKPC, blaNDM, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, vanA, mecA, ermB, ermF, tetM, aph(3′)-IIIa and mcr-1) and the class 1 integron gene (intI1). Negative and positive controls were used for each set of PCR primers. PCR amplification reactions were conducted in 20 μl volumes containing 1× PCR Master Mix (Tsingke, China), 1.0 μl template DNA, and 0.5 μM of each primer. After amplification, 5 μl samples of the PCR products were loaded on a 1.0% agarose gel containing GoldView, and separated electrophoretically in 1 × TAE buffer at 120 V for 20 min and visualized.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

To compare the abundance of ARGs for different sampling sites, the gene copy numbers of the sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, ermB, blaCTX-M, and tetM genes were quantified using qPCR assays. These genes confer resistance to five major classes of antibiotics: sulphonamides, aminoglycosides, macrolides, β-lactams, and tetracyclines. The levels of mcr-1 and 16S rRNA genes were also quantified. To quantitate the amounts of these genes, the levels were compared to the levels in standard samples prepared from plasmids containing these specific genes, as described previously (Chen and Zhang, 2013). The standard samples were diluted to yield a series of 10-fold concentrations and were subsequently used to generate qPCR standard curves. The R2 values were higher than 0.990 for all standard curves. The 20 μl qPCR mixtures contained 10 μL of SYBR premix Ex TaqTM (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), 0.5 μM of each forward and reverse primer, and 1 μl of template DNA. The final volume was adjusted to 20 μl by addition of DNase-free water. The IQTM5 real-time PCR system was employed for amplification and quantification, using the following protocol: 30 s at 95°C, 40 cycles of 5 s at 95°C, 30 s at the annealing temperature, and extension for another 30 s at 72°C. For detection, simultaneous fluorescence signal was scanned at 72°C, followed by a melt curve stage with temperature ramping from 65 to 95°C. Details of the qPCR primers of the target genes and the annealing temperatures are given in Table 2. The method design was adopted from prior research (Thornton and Basu, 2011). The copy numbers of the selected ARGs were normalized against the 16S rRNA gene copy number. Therefore, the copy number unit is described as copies/16S.

Table 2.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction primer pairs used in this study.

| Target genes | Sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon size(bp) | Annealing temperatures (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sul1 | CACCGGAAACATCGCTGCA | 158 | 60 | Luo et al., 2010 |

| AAGTTCCGCCGCAAGGCT | ||||

| aac(6′)-Ib-cr | GTTTCTTCTTCCCACCATCC | 103 | 60 | Yang et al., 2018 |

| AGTCCGTCACTCCATACATTG | ||||

| ermB | CACCGAACACTAGGGTTGC | 129 | 55 | This study |

| TGTGGTATGGCGGGTAAGT | ||||

| bla CTX-M | CAGATTCGGTTCGCTTTCAC | 103 | 55 | Yang et al., 2018 |

| GCAAATACTTTATCGTGCTGATG | ||||

| mcr-1 | CATCGCGGACAATCTCGG | 116 | 56 | Yang et al., 2017 |

| AAATCAACACAGGCTTTAGCAC | ||||

| tetM | TTCAGGTTTACTCGGTTCA | 106 | 55 | This study |

| GAAGTTAAATAGTGTTCTTGGAG | ||||

| 16S rRNA | CGGTGAATACGTTCYCGG | 128 | 55 | Suzuki et al., 2000 |

| GGWTACCTTGTTACGACTT |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 (IBM, United States). One-Way ANOVA was employed to analyze the results and values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

The Prevalence of mcr-Positive Isolates in the Funan River

The screening of 1500 isolates for mcr yielded a total of 24 mcr-positive isolates. They included 18 mcr-1 positive isolates (17 Escherichia coli and 1 Enterobacter cloacae) and 6 mcr-3 positive isolates (2 Aeromonas veronii and 4 Aeromonas hydrophila). mcr-2, mcr-4, or mcr-5 were not observed in any of the isolates.

Many reports have described the presence in mcr-1 in animal- and human- derived Enterobacteriaceae isolates isolated worldwide (Du et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Malhotra-Kumar et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016), but only two previous studies identified mcr-1 in waterborne Enterobacteriaceae. One study reported detection of the mcr-1 gene in 1 out of 74 Enterobacteriaceae isolated from 21 rivers and lakes in Switzerland that produced extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (Zurfuh et al., 2016). In a separate study, similar to our results, Zhou et al. (2017) isolated 23 mcr-1-positive isolates from environmental water sources in Hangzhou, indicating that mcr-1-carrying Enterobacteriaceae may be common in lakes and rivers in China. Data addressing the prevalence of mcr-3 is limited. Recently, a novel mcr variant, mcr-3, was first discovered on an IncI2 plasmid from a strain of E. coli isolated from a pig in China (Yin et al., 2017). Since then, mcr-3-positive strains have been identified in humans and food (Ling et al., 2017; Liu L. et al., 2017). Worryingly, mcr-3 has been detected on the chromosome of Aeromonas veronii, and these chromosomally encoded mcr-3 determinants can become plasmid-bound and transferable (Cabello et al., 2017; Ling et al., 2017). Recently, Shen et al. (2018a) presented evidence that mcr determinants originated from aquatic environments, including mcr-3 harboring Aeromonas spp. Because Aeromonas species are prevalent in aquatic environments, the occurrence of colistin resistant isolates in urban rivers is of great concern as these strains may contribute to the potential dissemination of mcr determinants.

Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes and Genotypes of mcr-1 and mcr-3-Positive Strains

As shown in Table 3, we next analyzed the antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and genotypes of the isolated mcr-1 and mcr-3 positive strains, and found 21 (87.5%) multidrug resistance isolates. The antimicrobial resistance testing showed that all isolates were resistant to colistin (MIC ≥ 4 μg/mL). Of the other antimicrobials tested, the most frequent resistance was to CTX (75%, 18 isolates), followed by CAZ (50%, 12 isolates), AMP (50%, 12 isolates), CRO (45.8%, 11 isolates), ATM (45.8%, 11 isolates), SXT (41.7%, 10 isolates), FOS (29.2%, 7 isolates), TE (25%, 6 isolates), AK (20.8%, 5 isolates), CIP (20.8%, 5 isolates), IPM (16.7%, 4 isolates), FOX (12.5%, 3 isolates), AMC (12.5%, 3 isolates), and ETP (4.2%, 1 isolate). The high occurrence of ESBL producers is worrisome, and corresponds to Zurfluh et al. (2013) who found 74 ESBL-producing isolates from 21 (36.2%) of 58 rivers and lakes, and all showed the multidrug resistance phenotype. In another study, 70% of fluoroquinolone resistant E. coli isolated from an urban river showed resistance to three or more classes of antibiotics (Zurfluh et al., 2014). The widespread distribution of MDR bacteria suggested serious drug-resistant pollution in river water. In this study, cephalosporin resistant strains were found most frequently, which may be related to the extensive use of cephalosporins for clinical and veterinary purposes. Overall, high usage has led to increased occurrence and wide distribution of ESBLs in bacteria (Bradford, 2001; Bonnet, 2004).

Table 3.

The antimicrobial resistance genotypes, phenotypes and MIC values of colistin of mcr-1 and mcr-3 positive strains.

| Isolates | Species | Antibiotic resistant genes | Antimicrobial resistance phenotypesa | MIC values of colistin (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E22 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | CTX, CAZ, AMP, ATM | 16 |

| E23 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | CTX, CAZ | 16 |

| E24 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | CTX, CAZ | 16 |

| E25 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | CTX, CAZ, ATM | 16 |

| E26 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | CTX, CAZ, ATM, AK | 16 |

| E27 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, sul2 | CRO, ATM, SXT | 16 |

| E28 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | CTX, CRO, CAZ, ATM, AK | 16 |

| E29 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, blaCTX-M-9, fosA3, qnrS, floR, oqxAB, sul1, sul2, tetA, aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX, CRO, AMP, SXT, CIP | 16 |

| E30 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, sul1, tetA | CRO, FOX, ATM, SXT, FOS, TE | 16 |

| E31 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, floR, sul2, tetM | CTX, CRO, CAZ, SXT | 16 |

| E32 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, floR, sul2, tetM | CTX, CRO, CAZ, SXT | 16 |

| E33 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, floR, sul2, tetM | CTX, CRO, CAZ, SXT | 16 |

| E34 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, blaTEM, blaCTX-M-9 | CTX, CRO, CAZ, AMP | 16 |

| E35 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, blaTEM, blaCTX-M-9, floR, oqxAB, sul1, sul2, tetM, tetA, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, rmtB | CTX, CRO, FOX, AMP, ATM, SXT, TE, AK, CIP | 16 |

| E36 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, blaTEM, blaCTX-M-9, fosA3, oqxAB, sul1, sul2 | CTX, CRO, AMP, ATM, SXT, FOS, CIP | 16 |

| E38 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, tetM, tetA | CTX, CAZ, AMP, ATM, TE | 16 |

| E39 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1, qnrS, tetA | CTX, ATM, AMC, TE, FOS, CIP | 8 |

| E37 | Enterobacter cloacae | mcr-1, floR, sul2, rmtA, rmtB | CTX, FOX, AMP, AMC, SXT, AK, IPM | 16 |

| A4 | Aeromonas veronii | mcr-3, blaSHV, sul1 | CTX, IPM | 4 |

| A19 | Aeromonas hydrophila | mcr-3, blaTEM, blaCTX-M-9, qnrB, sul1, sul2, tetA | CTX, CRO, CAZ, AMP, ATM, AMC, FOS, TE, IPM | 16 |

| A48 | Aeromonas hydrophila | mcr-3, sul1, rmtA, rmtB | AMP, FOS | 8 |

| A49 | Aeromonas hydrophila | mcr-3, sul1, sul2, rmtA, rmtB | AMP, FOS, AK | 8 |

| A52 | Aeromonas hydrophila | mcr-3, qnrS, floR, sul1, tetA | AMP, FOS, TE CIP | 4 |

| A54 | Aeromonas veronii | mcr-3, sul1 | AMP, SXT, IPM, ETP | 4 |

aCTX, cefotaxime; CRO, ceftriaxone; CAZ, ceftazidime; FOX, cefoxitin; AMP, ampicillin; ATM, aztreonam; AMC: amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; FOS, fosfomycin; TE, tetracycline; AK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; IPM, imipenem; ETP, ertapenem.

The mcr-1 and mcr-3 positive isolates were next assayed for the presence of other ARGs. The blaSHV, blaTEM and blaCTX-M-9 genes were detected in 1 (4.2%), 4 (16.7%), and 5 (20.8%) isolates, respectively. None of the isolates were positive for blaKPC, blaOXA-48, blaNDM, blaV IM, blaIMP or blaCTX-M-1. Fifteen (62.5%) of isolates contain sulphonamide resistance genes (sul1 in 5 isolates, sul2 in 5 isolates, and sul1/sul2 combined in 5 isolates). Some isolates contained genes encoding tetracycline resistance, with 20.8% and 29.2% positive for tetM and tetA genes, respectively. Some isolates contained genes encoding fluoroquinolone resistance genes, qnrB, qnrS, and oqxAB, which were detected in 1(4.2%), 3(12.5%), and 3(12.5%) isolates, respectively. Genes associated with aminoglycoside resistance, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, rmtA, and rmtB, were amplified in 2 (8.3%), 3 (12.5%), and 4 (16.7%) isolates, respectively. The floR gene was detected in 7 (29.2%) isolates and the fosA3 gene was identified in 2 (8.3%) isolates. According to a recent report, 77.3% of mcr-1-positive E. coli (34/44) carried at least 1 ESBL gene, and several isolates carried 3 or more ESBL genes (Wu et al., 2018). Furthermore, blaCTX-M-9 was one of the most prevalent genes among the identified ESBL genes in China (Liu et al., 2015). Consistent with previous reports, sulphonamides and tetracycline resistance genes are the most abundant ARGs in rivers (Yang et al., 2018). We identified two strains (E29 and E36) that carried mcr-1, fosA3, and blaCTX-M-9 genes from river samples (Table 3). The mcr-1, fosA3, and ESBLs genes were previously identified in E. coli isolated from animal and food samples (Liu X. et al., 2017; Lupo et al., 2018), and the presence of these multidrug-resistant strains in urban river may present a serious threat to public health.

Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Funan River

In this study, the prevalence of ARGs in water samples was investigated by sampling various sites along the Funan River. The sul1, qnrS, tetM, and intI1 genes were detected in samples from all 10 sampling sites (100%). Additionally, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, sul2, aph(3′)-IIIa, ermB, and blaCTX-M were detected at high rates of 90%, 90%, 90%, 80% and 70%, respectively. Many studies have reported the presence of these genes in aquatic environments (Hu et al., 2008; D’Costa et al., 2011; van Hoek et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2015; Makowska et al., 2016). Interestingly, the aph(3′)-IIIa gene has rarely been reported in river water microorganisms, but has been reported in clinical specimens (Tuhina et al., 2016). The detection of the aph(3′)-IIIa gene was high in this study, suggesting contamination of the Funan River with resistant bacteria carrying the aph(3′)-IIIa gene.

Genes conferring resistance to the last line of antibiotics, including mcr-1, blaNDM, blaKPC and vanA genes, were detected at rates of 30%, 20%, 10%, and 10%, respectively. blaV IM was not detected at any site. The mcr-1 gene was detected in 30% of samples, suggesting the Funan River could act as a reservoir for the mcr-1 gene. The blaNDM, blaKPC and vanA genes were detected near the WWTP (Figure 1). Although mcr-1 is found frequently in human and animal settings, there is only limited data for urban rivers (Marathe et al., 2017; Ovejero et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). Similarly, Marathe et al. detected blaNDM and blaKPC genes in the sediments of an Indian river (Marathe et al., 2017). Although a blaV IM positive carbapenem-resistant strain was isolated from a river in Switzerland (Zurfluh et al., 2013), here is a lack of data on blaV IM in the non-clinical environment. The vanA gene is associated with vancomycin resistance and has been found in wastewater biofilms and in drinking water biofilms in Mainz (Schwartz et al., 2003). Although these genes have rarely been identified in natural aquatic environments, given the dangerous infections that can arise from ARB (and which subsequently create intractable challenges for clinical treatment), further observation of the prevalence of these genes in aquatic environments is required.

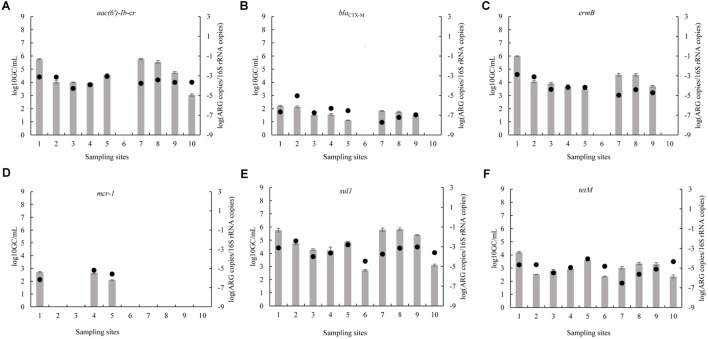

Abundance of ARGs

Concerning the absolute abundance of ARGs in the Funan River, ARGs were detected at levels that ranged from 0 to 6.0 log10 GC/mL (Figure 2). The sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and ermB genes were the dominant ARGs in the Funan River with mean absolute abundances of 4.8, 4.1, and 3.4 log10 GC/mL, respectively. The sul1 gene exhibited the most prominent average abundance in water samples. Previous studies reported that sul1 is abundant in numerous water areas, including the Tordera River Basin (Proia et al., 2016) and the Haihe River (Luo et al., 2010). Although the mcr-1 gene was not detected in water samples at some sites, three sites (RWW, HWW1, and HWW2) displayed 2.0-2.7 log10 GC/mL. Notably, the highest detected level of mcr-1 (2.7 log10 GC/mL) was higher than that in previous reports about the Haihe river (2.6 log10 GC/mL) (Yang et al., 2017). The absence of mcr in some samples may indicate that no mcr-1 positive strains were present in the water samples or that the levels of mcr-1 were below the detection limit. Site RWW is located near the residential sewage outlet, suggesting the presence of mcr-1 was related to human activity. Consistently, mcr-1 was detected at HWW1 and HWW2, adjacent to the hospital sewage outlets, suggesting the spread of mcr-1 from hospitals to urban river, although colistin is not used widely in human medicine. The mcr-1 abundance at RWW (2.7 log10 GC/mL) was slightly higher than that at HWW1 (2.6 log10 GC/mL) and at HWW2 (2.3 log10 GC/mL). Similarly, the prevalence of mcr-1-positve E. coli from healthy individuals (0.7–6.2%) is higher than the prevalence for inpatients (0.4–2.9%) (Shen et al., 2018b). It is striking that mcr is the only gene that was absent from sites other than RWW and HWW. The reasons for high rate of fecal carriage of mcr in humans in China may reflect the rapid emergence of plasmid-encoded mcr-1 within many MDR E. coli carried by humans and also be related to the significant diversity and genetic flexibility of MGEs harboring mcr-1 (Zhong et al., 2018).

FIGURE 2.

Absolute (bars) and 16S rRNA gene-normalized (symbols) levels of ARGs (A: aac(6′)-Ib-cr; B: blaCTX-M; C: ermB; D: mcr-1; E: sul1; F: tetM) in water samples collected at various sites (1, RWW, Residential wastewater; 2, P1, Park1; 3, P2, Park2; 4, HWW1, Hospital Wastewater1; 5, HWW2, Hospital Wastewater2; 6, P3, Park3; 7, RI, River Intersection; 8, WWTP, Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant; 9, UWP, Upstream of Wetland Park; 10, DWP, Downstream of Wetland Park) along the Funan River.

At RWW, RI, and WWTP, the absolute abundances of certain ARGs (sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and ermB) were significantly higher than those at other sampling sites (P < 0.05). At P3 and DWP, the absolute abundances of most ARGs were significantly lower than the levels detected at the other sites (P < 0.05). RWW was associated with the highest absolute abundance of the six ARGs (mcr-1, sul1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, ermB, blaCTX-M, and tetM) (Figure 2). Samples near the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) and densely populated areas exhibited a relatively greater content of resistant genes. Wastewater discharge may contribute to the spread of ARGs into the environment, thereby affecting the bacterial communities of the receiving river (Marti et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2015). Our results indicate that human activities influence the dissemination of resistance genes in the Funan River. Remarkably, the absolute abundances of most ARGs were low at the DWP sampling point, located downstream of the wetland park. This is consistent with a decrease in the ARGs levels of the effluents from a constructed wetland with a free surface flow (Liu et al., 2014).

As shown in Figure 2, the relative abundances of each ARG are only partly correlated with their absolute abundance. That is, although the absolute abundances of most ARGs at RWW, RI and WWTP were relatively high, their relative abundances were comparatively low. These differences may be related to the differences in the proportion of resistant bacteria to total bacteria at each site (Tao et al., 2014).

Conclusion

This study describes 18 mcr-1-positive strains and 6 mcr-3-positive strains isolated from the Funan River, of which 87.5% were found to be MDR. The sul1, sul2, intI1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaCTX-M, tetM, ermB, qnrS and aph(3′)-IIIa genes were abundant in the Funan River. Interestingly, the mcr-1, blaKPC, blaNDM, and vanA genes were detected, although these four resistance genes have rarely been found in natural river systems. Notably, the mcr-1 gene was detected at a rate of 30%. Our results suggest urban activities may increase the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes and demonstrate the current presence of drug-resistance pollution in the Funan River. The processes by which the dissemination of ARGs occurs in urban rivers should be the focus of future studies.

Author Contributions

AZ designed the study. HT, DL, XX, and PL carried out the sampling work. HT, YY, XT, and JG performed the experiments. AZ, HT, RX, LK, and CL analyzed the data. AZ, HT, YL, and HW drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFD0500300), the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31572548), the Applied Basic Research Program in Sichuan Province (2018JY0572), and the Science & Technology Pillar Program in Sichuan Province (2018HH0027).

References

- Adefisoye M. A., Okoh A. I. (2016). Identification and antimicrobial resistance prevalence of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains from treated wastewater effluents in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Microbiologyopen 5143–151. 10.1002/mbo3.319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinbowale O. L., Peng H., Barton M. D. (2006). Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from aquaculture sources in Australia. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100 1103–1113. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendonk T. U., Manaia C. M., Merlin C., Fatta-Kassinos D., Cytryn E., Walsh F., et al. (2015). Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 310–317. 10.1038/nrmicro3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet R. (2004). Growing group of extended-spectrum-lactamases: the CTX-M Enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 48 1–14. 10.1128/AAC.48.1.1-14.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak M., Fischer J., Hammerl J. A., Hendriksen R. S., Szabo I., Malorny B. (2017). Identification of a novel transposon-associated phosphoethanolamine transferase gene, mcr-5, conferring colistin resistance in d-tartrate fermenting Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3317–3324. 10.1093/jac/dkx327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford P. A. (2001). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14 933–951. 10.1128/CMR.14.4.933-951.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello F., Tomova A., Ivanova L., Godfrey H. (2017). Aquaculture and mcr colistin resistance determinants. mBio 8:e01229-17. 10.1128/mBio.01229-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Villa L., Feudi C., Curcio L., Orsini S., Luppi A., et al. (2017). Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-4 gene in Salmonella and Escherichia coli, Italy 2013, Spain and Belgium, 2015 to 2016. Euro. Surveill. 22:30589. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.31.30589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang M. (2013). Occurrence and removal of antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater and rural domestic sewage treatment systems in eastern China. Environ. Int. 55 9–14. 10.1016/j.envint.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloeckaert A., Baucheron S., Flaujac G., Schwarz S., Kehrenberg C., Martel J. L., et al. (2000). Plasmid-mediated florfenicol resistance encoded by the floR gene in Escherichia coli isolated from cattle. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 44 2858–2860. 10.1128/AAC.44.10.2858-2860.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2016). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Sixth Informational Supplement M100S. Wayne,PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- D’Costa V. M., King C. E., Kalan L., Morar M., Sung W. W., Schwarz C., et al. (2011). Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477 457–461. 10.1038/nature10388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Chen L., Tang Y. W., Kreiswirth B. N. (2016). Emergence of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 16 287–288. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00056-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhar F., Seyedpour S. M. (2015). Prevalence of qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from imam hussein hospital in Tehran. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 40 515–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST (2017). European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Clinical Breakpoints – Bacteria (v. 7.0). Available at: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_7.1_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hou J., Huang X., Deng Y., He L., Yang T., Zeng Z., et al. (2012). Dissemination of the fosfomycin resistance gene fosA3 with CTX-M beta-lactamase genes and rmtB carried on IncFII plasmids among Escherichia coli isolates from pets in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 2135–2138. 10.1128/AAC.05104-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Shi J., Chang H., Li D., Yang M., Kamagata Y. (2008). Phenotyping and genotyping of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from a natural river basin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 3415–3420. 10.1021/es7026746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J., Kim J. H., Park J. H., Lee Y. J., Lee J. H. (2011). Molecular and virulence characteristics of multi-drug resistant Salmonella enteritidis strains isolated from poultry. Vet. J. 189 306–311. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafil H. S., Asgharzadeh M. (2014). Vancomycin-resistant Enteroccus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis isolated from education hospital of Iran. Maedica 9 323–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Yuan K., Liang X., Chen X., Zhao Z., Yang Y., et al. (2015). Occurrences and distribution of sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes in the Yangtze River Estuary and nearby coastal area. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 100 304–310. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z., Yin W., Li H., Zhang Q., Wang X., Wang Z., et al. (2017). Chromosome-mediated mcr-3 variants in Aeromonas veronii from chicken meat. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e01272-17. 10.1128/AAC.01272-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., He D., Lv L., Liu W., Chen X., Zeng Z., et al. (2015). blaCTX-M-1/9/1 hybrid genes may have been generated from blaCTX-M-15 on an IncI2 plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 4464–4470. 10.1128/AAC.00501-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Liu Y. H., Wang Z., Liu C. X., Huang X., Zhu G. F. (2014). Behavior of tetracycline and sulfamethazine with corresponding resistance genes from swine wastewater in pilot-scale constructed wetlands. J. Hazard. Mater. 278 304–310. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Li R., Zheng Z., Chen K., Xie M., Chan E. W., et al. (2017). Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli isolates carrying mcr-1, fosA3, and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase genes from food samples in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e00064-17. 10.1128/AAC.00064-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Feng Y., Zhang X., McNally A., Zong Z. (2017). New variant of mcr-3 in an extensively drug-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolate carrying mcr-1 and blaNDM-5. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61 e1757–e1717. 10.1128/AAC.01757-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Y., Wang Y., Walsh T. R., Yi L. X., Zhang R., Spencer J., et al. (2016). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 161–168. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Mao D., Rysz M., Zhou Q., Zhang H., Xu L., et al. (2010). Trends in antibiotic resistance genes occurrence in the Haihe river, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 7220–7225. 10.1021/es100233w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo A., Saras E., Madec J. Y., Haenni M. (2018). Emergence of blaCTX-M-55 associated with fosA, rmtB and mcr gene variants in Escherichia coli from various animal species in France. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73 867–872. 10.1093/jac/dkx489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowska N., Koczura R., Mokracka J. (2016). Class 1 integrase, sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes in wastewater treatment plant and surface water. Chemosphere 144 1665–1673. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra-Kumar S., Xavier B. B., Das A. J., Lammens C., Hoang H. T. T., Pham N. T., et al. (2016). Colistin-resistant Escherichia coli harbouring mcr-1 isolated from food animals in Hanoi. Vietnam. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 16 286–287. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00014-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe N. P., Pal C., Gaikwad S. S., Jonsson V., Kristiansson E., Larsson D. G. J. (2017). Untreated urban waste contaminates Indian river sediments with resistance genes to last resort antibiotics. Water Res. 124 388–397. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.07.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti E., Jofre J., Balcazar J. L. (2013). Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial community composition in a river influenced by a wastewater treatment plant. PLoS One 8:e78906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel D., Dychinco B., Webb V. A., Davies J. (2000). Antibiotic resistance in the ECOR collection: integrons and identification of a novel aad gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44 1568–1574. 10.1128/AAC.44.6.1568-1574.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyra R. C., Frisancho J. A., Rinsky J. L., Resnick C., Carroll K. C., Rule A. M., et al. (2014). Multidrug-resistant and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hog slaughter and processing plant workers and their community in North Carolina (USA). Environ. Health Perspect. 122 471–477. 10.1289/ehp.1306741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovejero C. M., Delgado-Blas J. F., Calero-Caceres W., Muniesa M., Gonzalez-Zorn B. (2017). Spread of mcr-1-carrying Enterobacteriaceae in sewage water from Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 1050–1053. 10.1093/jac/dkw533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson G. K., Larsen A. R., Robb A., Edwards G. E., Pennycott T. W., Foster G., et al. (2012). The newly described mecA homologue, mecALGA251, is present in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a diverse range of host species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2809–2813. 10.1093/jac/dks329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proia L., von Schiller D., Sànchez-Melsió A., Sabater S., Borrego C. M., Rodríguez-Mozaz S., et al. (2016). Occurrence and persistence of antibiotic resistance genes in river biofilms after wastewater inputs in small rivers. Environ. Pollut. 210 121–128. 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruden A., Pei R., Storteboom H., Carlson K. H. (2006). Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: studies in Northern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 7445–7450. 10.1021/es060413l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Goldstein R. E., Micallef S. A., Gibbs S. G., Davis J. A., He X., George A., et al. (2012). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) detected at four U.S. wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Health Perspect. 120 1551–1558. 10.1289/ehp.1205436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz T., Kohnen W., Jansen B., Obst U. (2003). Detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and their resistance genes in wastewater, surface water, and drinking water biofilms. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 43 325–335. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2003.tb01073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Yin W., Liu D., Shen J., Wang Y. (2018a). Reply to Cabello et al, “Aquaculture and mcr colistin resistance determinants. mBio. 9:e01629-18. 10.1128/mBio.01629-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Zhou H., Xu J., Wang Y., Zhang Q., Walsh T., et al. (2018b). Anthropogenic and environmental factors associated with high incidence of mcr-1 carriage in humans across China. Nat. Microbiol. 3 1054–1062. 10.1038/s41564-018-0205-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Wang Y., Shen Y., Shen J., Wu C. (2016). Early emergence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 16:293. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00061-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. T., Taylor L. T., DeLong E. F. (2000). Quantitative analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes in mixed microbial populations via 5’-nuclease assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 4605–4614. 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4605-4614.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao C. W., Hsu B. M., Ji W. T., Hsu T. K., Kao P. M., Hsu C. P., et al. (2014). Evaluation of five antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment systems of swine farms by real-time PCR. Sci. Total Environ. 496 116–121. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton B., Basu C. (2011). Real-time PCR (qPCR) primer design using free online software. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 39 145–154. 10.1002/bmb.20461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuhina B., Anupurba S., Karuna T. (2016). Emergence of antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors among the unusual species of enterococci, from North India. Indian. J. Pathol. Microbiol. 59 50–55. 10.4103/0377-4929.174795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo E. E., Dashti A. A. (2000). Detection of genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes in staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction and dot blot hybridization. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 13 273–279. 10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek A. H., Mevius D., Guerra B., Mullany P., Roberts A. P., Aarts H. J. (2011). Acquired antibiotic resistance genes: an overview. Front. Microbiol. 2:203 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang A., Yang Y., Lei C., Jiang W., Liu B., et al. (2017). Emergence of Salmonella enterica serovar Indiana and California isolates with concurrent resistance to cefotaxime, amikacin and ciprofloxacin from chickens in China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 262 23–30. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Wang Y., Shi X., Wang S., Ren H., Shen Z., et al. (2018). Rapid rise of the ESBL and mcr-1 genes in Escherichia coli of chicken origin in China, 2008-2014. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7:30. 10.1038/s41426-018-0033-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier B. B., Lammens C., Ruhal R., Kumar-Singh S., Butaye P., Goossens H., et al. (2016). Identification of a novel plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene, mcr-2, in Escherichia coli, Belgium, June 2016. Euro. Surveill. 21 10.2807/1560-7917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Xu Y., Wang H., Guo C., Qiu H., He Y., et al. (2015). Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in a sewage treatment plant and its effluent-receiving river. Chemosphere 119 1379–1385. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Qiu Z., Shen Z., Zhao H., Jin M., Li H., et al. (2017). The occurrence of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in the Haihe river (China). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:E576. 10.3390/ijerph14060576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Shi W., Lu S. Y., Liu J., Liang H., Yang Y., et al. (2018). Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteriophage DNA fraction from Funan River water in Sichuan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 626 835–841. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W., Li H., Shen Y., Liu Z., Wang S., Shen Z., et al. (2017). Novel Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. mBio 8:e00543-17. 10.1128/mBio.00543-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavascki A. P., Goldani L. Z., Li J., Nation R. L. (2007). Polymyxin B for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pathogens: a critical review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60 1206–1215. 10.1093/jac/dkm357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Chen M., Sui Q., Wang R., Tong J., Wei Y. (2016). Fate of antibiotic resistance genes and its drivers during anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and sewage sludge based on microwave pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 217 28–36. 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.02.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Zhang J., Ji J., Fang Y., Shen P., Ying C., et al. (2015). Emergence of Raoultella ornithinolytica coproducing IMP-4 and KPC-2 carbapenemases in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 7086–7089. 10.1128/AAC.01363-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L., Phan H., Shen C., Vihta K., Sheppard A., Huang X., et al. (2018). High rates of human fecal carriage of mcr-1-positive multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae emerge in china in association with successful plasmid families. Clin. Infect. Dis. 66 676–685. 10.1093/cid/cix885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. W., Zhang T., Ma J. H., Fang Y., Wang H. Y., Huang Z. X., et al. (2017). Occurrence of plasmid- and chromosome-carried mcr-1 in waterborne Enterobacteriaceae in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e00017-e17. 10.1128/AAC.00017-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfluh K., Abgottspon H., Hächler H., Nüesch-Inderbinen M., Stephan R. (2014). Quinolone resistance mechanisms among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli isolated from rivers and lakes in Switzerland. PLoS One 9:e95864. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfluh K., Bagutti C., Brodmann P., Alt M., Schulze J., Fanning S., et al. (2017). Wastewater is a reservoir for clinically relevant carbapenemase and 16S rRNA methylase producing Enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 50 436–440. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfluh K., Hächler H., Nüesch-Inderbinen M., Stephan R. (2013). Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from rivers and lakes in Switzerland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 3021–3026. 10.1128/AEM.00054-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfuh K., Poirel L., Nordmann P., Nüesch-Inderbinen M., Hächler H., Stephan R. (2016). Occurrence of the Plasmid-borne mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in river water and imported vegetable samples in Switzerland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 2594–2595. 10.1128/AAC.00066-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]