Abstract

Background

Hyperglycemia on-admission is a powerful predictor of adverse events in patients presenting for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Aim

In this study, we sought to determine the prognostic value of hyperglycemia on-admission in Tunisian patients presenting with STEMI according to their diabetic status.

Methods

Patients presenting to our center between January 1998 and September 2014 were enrolled. Hyperglycemia was defined as a glucose level ≥11 mmol/L. In-hospital prognosis was studied in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The predictive value for mortality of glycemia level on-admission was assessed by mean of the area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve calculation.

Results

A total of 1289 patients were included. Mean age was 60.39 ± 12.8 years and 977 (77.3%) patients were male. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 70.2% and 15.2% in patients presenting with and without hyperglycemia, respectively (p < 0.001). In univariate analysis, hyperglycemia was associated to in-hospital death in diabetic (OR: 8.85, 95% CI: 2.11–37.12, p < 0.001) and non-diabetic patients (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.39–4.74, p = 0.002). In multivariate analysis, hyperglycemia was independently predictive of in-hospital death in diabetic patients (OR: 9.6, 95% CI: 2.18–42.22, p = 0.003) but not in non-diabetic patients (OR: 1.93, 95% CI: 0.97–3.86, p = 0.06). Area under ROC curve of glycemia as a predictor of in-hospital death was 0.792 in diabetic and 0.676 in non-diabetic patients.

Conclusion

In patients presenting with STEMI, hyperglycemia was associated to hospital death in diabetic and non-diabetic patients in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, hyperglycemia was independently associated to in-hospital death in diabetic but not in non-diabetic patients.

Keywords: Hyperglycemia, Diabetes mellitus, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, Mortality

1. Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are a leading cause of death worldwide. Although declining, short and long term mortality rates in patients presenting for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remain highly preoccupying.1 Compared to non-diabetic patients, diabetic ones are known to carry worse early and late outcomes.2 On the other hand, and depending on the definition used, prevalence of hyperglycemia in different epidemiological studies ranges from 3% to 71% of patients hospitalized for ACS.3 In patients presenting for STEMI, hyperglycemia on-admission has already been identified as a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes regardless to the implementation of a reperfusion therapeutic either by thrombolysis or primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI).4, 5 Nevertheless, controversy remains as for a possible interaction between diabetic status and the prognostic value of hyperglycemia in patients presenting for STEMI.

In the present study, we sought to determine the prognostic impact on early outcomes of hyperglycemia on-admission in diabetic and non-diabetic patients presenting for acute STEMI in the Tunisian context.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and design

This study was carried-out on data from our single center STEMI registry. The registry enrolls all consecutive patients aged ≥18 years admitted to our cardiology department for STEMI. Data are collected retrospectively in a periodical manner every one to two years and updated for long-term outcomes when needed. Patients included in the present study were enrolled between January 1998 and September 2014. Patients are referred to our coronary care unit (CCU) or directly to the catheterization laboratory via the emergency department or the local Emergent Medical Aid system. The diagnosis of STEMI was established in the presence of persistent chest discomfort or pain (>20 min) concurrently to the presence of an ST-segment elevation on two adjacent leads or a presumably new left bundle branch block on electrocardiogram. Clinical history and physical examination were recorded in all patients. Patients are managed as in accordance as possible with the European Society of Cardiology guidelines on coronary revascularization.6 Decision to opt for a specific revascularization modality (i.e. thrombolysis or pPCI) was let to the senior operator. Patients managed conservatively (i.e. with no revascularization therapy) were so for several reasons (advanced age, late presentation…). All patients received upon diagnosis 100 IU of unfractionated heparin intravenously, 250 mg aspirin and 300 mg or 600 mg clopidogrel orally depending on the reperfusion modality chosen. Patients aged 75 and older received only 75 mg clopidogrel orally.

Glycemic level and other biologic tests were obtained upon admission and thereafter as needed. In accordance with other published studies,7, 8, 9 hyperglycemia on-admission was defined as glycemia ≥11 mmol/L. Heart failure on-admission was defined as Killip II or III class. Cardiogenic shock was referred to as Killip IV class. Renal failure was defined as a creatinine clearance <45 ml/min on-admission in patients not known to have chronic kidney disease. Bleeding referred to any overt hemorrhage leading to a drop ≥2 g/dL of hemoglobin or requiring blood transfusion.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed in absolute values and proportions. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Means were compared using the Student t-test for independent samples. Proportions between sub-groups were compared using the chi-square test. The latter was also used for determining predictive factors of death in univariate analysis. Results were expressed as odd ratios with accompanying 95% confidence interval. Multivariate analysis was performed using binary logistic regression in variables significantly associated to in-hospital death in univariate analysis. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. Glycemia level as a predictor of in-hospital death in diabetic and non-diabetic patients was studied using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. All analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) V. 21 for Windows.

3. Results

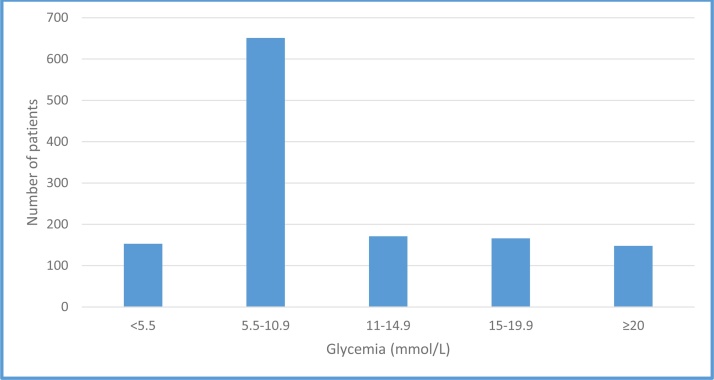

A total of 1498 patients were enrolled in the overall registry. Admission glucose level was available only in 1289 patients that were included in the present analysis. Mean age of the study population was 60.39 ± 12.8 years and 997 (77.3%) patients were male. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the study population was 36% with a mean duration of 9.89 ± 7.84 years. Fig. 1 depicts the distribution of the population study according to glycemia on-admission. Four hundred eighty five (38.5%) patients had a glycemia level ≥11 mmol/L. In patients with hyperglycemia, prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia was significantly higher whereas current smoking was more prevalent in the non-hyperglycemic group (Table 1). Anemia was also more prevalent in hyperglycemic patients. Regarding clinical presentation, patients with hyperglycemia were more at risk of presenting heart failure and cardiogenic shock on-admission. They also had a higher prevalence of acute renal failure on-admission.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of glycemic level on-admission in the study population.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, therapeutic modalities and in-hospital outcomes in the study population.

| Population (n = 1289) | Gly ≥ 11 mmol/L (n = 485) | Gly < 11 mmol/L (n = 804) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 997 (77.3%) | 343 (70.7%) | 654 (81.3%) | <0.001 |

| Age ≥75 years | 194 (15.1%) | 72 (14.8%) | 122 (15.2%) | 0.873 |

| Hypertension | 396 (30.7%) | 182 (37.5%) | 214 (26.6%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 464 (36%) | 342 (70.2%) | 122 (15.2%) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 148 (11.5%) | 75 (15.6%) | 73 (9.2%) | 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 869 (67.4%) | 273 (56.3%) | 596 (74.1%) | <0.001 |

| History of CAD | 141 (10.9%) | 56 (11.5%) | 85 (10.6%) | 0.854 |

| History of heart failure | 25 (1.9%) | 9 (1.9%) | 16 (2%) | 0.865 |

| Anemia | 406 (31.5%) | 171 (35.3%) | 235 (29.2%) | 0.024 |

| Heart failure on-admission | 282 (21.9%) | 131 (27%) | 151 (18.8%) | 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 29 (2.2%) | 17 (3.5%) | 12 (1.5%) | 0.018 |

| Acute renal failure | 106 (8.2%) | 57 (11.8%) | 49 (6.1%) | <0.001 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation | 92 (7.1%) | 43 (8.9%) | 49 (6.1%) | 0.061 |

| Thrombolysis | 445 (34.5%) | 157 (32.4%) | 288 (35.8%) | 0.207 |

| Primary PCI | 376 (29.2%) | 166 (34.2%) | 210 (26.1%) | 0.002 |

| Conservative medical treatment | 486 (37.7%) | 162 (33.4%) | 306 (38%) | 0.999 |

| Bleeding | 39 (3%) | 18 (3.7%) | 21 (2.6%) | 0.268 |

| In hospital mortality | 97 (7.5%) | 61 (12.6%) | 36 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| In primary PCI | 31 (8.2%) | 23 (13.9%) | 8 (3.8%) | <0.001 |

| In thrombolysis | 29 (6.5%) | 15 (9.6%) | 14 (4.9%) | 0.055 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Therapeutics implemented at the acute phase were comparable between the two sub-groups regarding thrombolysis use and conservative medical therapy. Nevertheless, pPCI was significantly more utilized in hyperglycemic group (34.2% vs. 26.1%, p = 0.002). In-hospital mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with hyperglycemia compared to those without (12.6% vs. 4.5%, p < 0.001).

We analyzed univariate predictors of in-hospital death in diabetic and non-diabetic patients (Table 2). Hyperglycemia on admission was significantly associated to in hospital death in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients (OR: 8.85, 95% CI: 2.11–37.12, p < 0.001 and OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.39–4.74, p = 0.002, respectively) along with other factors. In multivariate analysis (Table 3), hyperglycemia was independently predictive of in-hospital death in diabetic patients (OR: 9.6, 95% CI: 2.18–42.2, p = 0.003) but failed to reach statistical significance in non-diabetic patients (OR: 1.93; 95% CI: 0.97–3.86, p = 0.06).

Table 2.

Univariate predictors of in-hospital death in non-diabetic and diabetic patients.

| Non diabetic patients |

Diabetic patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Female gender | 1.25 | 0.62–2.51 | 0.517 | 1.8 | 0.99–3.42 | 0.05 |

| Age ≥75 years | 2.48 | 1.31–4.69 | 0.004 | 2.28 | 1.11–4.66 | 0.021 |

| Hypertension | 1.75 | 0.95–3.2 | 0.67 | 1.54 | 0.83–2.84 | 0.162 |

| Anemia | 3.65 | 2.05–6.51 | <0.001 | 2.19 | 1.18–4.05 | 0.011 |

| Heart failure on-admission | 7.33 | 4.05–13.26 | <0.001 | 3.86 | 2.07–7.2 | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 10.1 | 3.79–26.92 | <0.001 | 6.54 | 1.77–24.1 | 0.001 |

| Renal failure on-admission | 3.83 | 1.74–8.4 | <0.001 | 5.69 | 2.87–11.28 | <0.001 |

| Glycemia ≥11 mmol/L | 2.57 | 1.39–4.74 | 0.002 | 8.85 | 2.11–37.12 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding | 4.12 | 1.6–10.6 | 0.001 | 7.81 | 2.01–30.2 | <0.001 |

Table 3.

Multivariate predictors of in-hospital death in non-diabetic and diabetic patients.

| Non diabetic patients |

Diabetic patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age ≥75 years | 1.64 | 0.79–3.39 | 0.182 | 1.72 | 0.78–3.83 | 0.178 |

| Anemia | 2.79 | 1.46–5.34 | 0.002 | 1.71 | 0.86–3.41 | 0.123 |

| Heart failure on-admission | 5.49 | 2.88–10.48 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 1.57–6.13 | 0.001 |

| Renal failure on-admission | 2.29 | 0.91–5.75 | 0.076 | 4.28 | 2.01–9.1 | <0.001 |

| Glycemia ≥11 mmol/L | 1.93 | 0.97–3.86 | 0.06 | 9.6 | 2.18–42.22 | 0.003 |

| Bleeding | 3.27 | 1.12–9.54 | 0.03 | 5.82 | 1.28–26.52 | 0.023 |

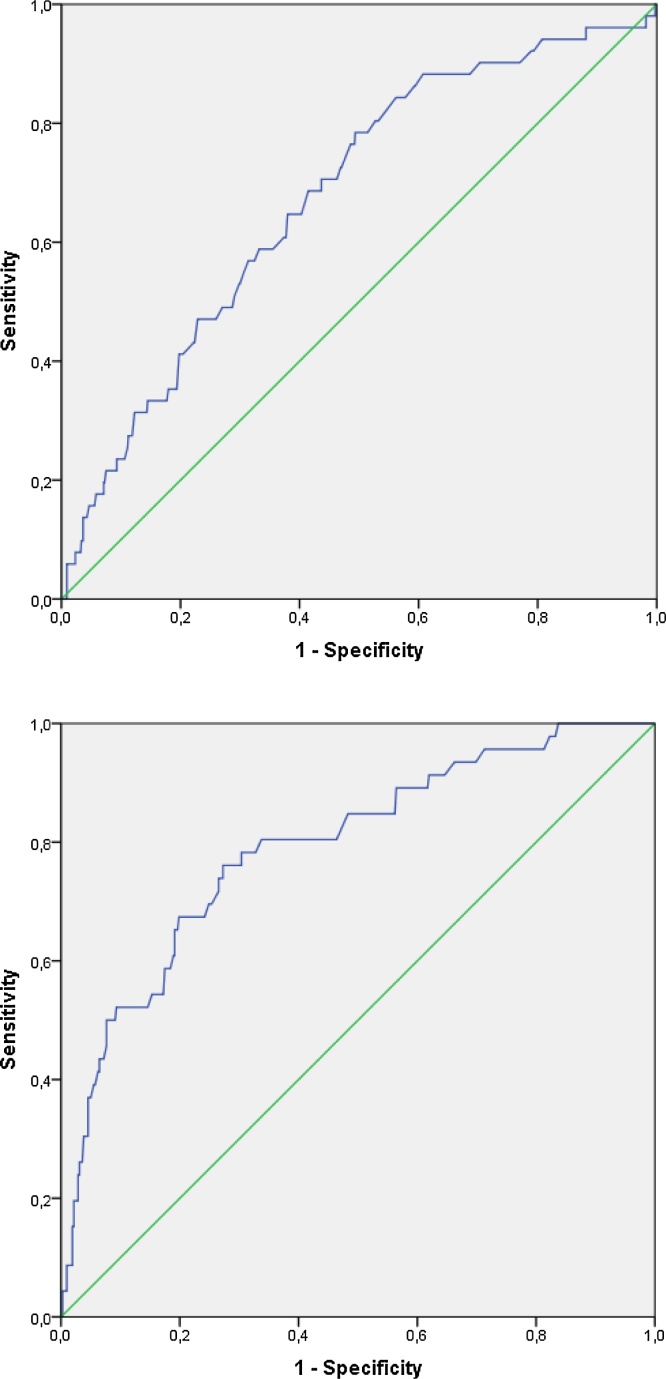

The value of glycemia level on admission as a predictor of in-hospital death was studied using the area under the ROC curve in diabetic and non-diabetic patients (Fig. 2). The area under the ROC curve was 0.792 in diabetic and 0.676 in non-diabetic patients. In diabetic patients, a cut-off glycemic level of 18.1 mmol/L predicted in-hospital death with a sensitivity of 76.1% and specificity of 70.3%. In non-diabetic patients, a cut-off at 8.04 mmol/L predicted in-hospital death with a sensitivity of 64.7% and a specificity of 62%.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for glycemia for in-hospital death prediction in non-diabetic (top) and diabetic (bottom) patients presenting for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction; area under ROC curve 0.676 for non-diabetic and 0.792 for diabetic patients.

4. Discussion

Hyperglycemia on-admission has been identified as a powerful predictor of poor in-hospital outcomes in patients presenting for ACS.10 The present study derived from a relatively large population highlights the prognostic value of hyperglycemia in patients presenting for STEMI regardless to the reperfusion strategy adopted. Furthermore, it identifies diabetic patients as a sub-group in which hyperglycemia has a better predictive value for in-hospital mortality.

In our study, patients presenting with hyperglycemia had significantly higher rates of heart failure, cardiogenic shock and in-hospital death. Concomitantly, they were more likely to have other aggravating conditions known to be associated to worse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease such as diabetes and hypertension. The relationship between glycemic level on-admission and short term prognosis has been thoroughly investigated in previous studies, however the mechanisms underlying the association between high serum glucose levels and mortality are not fully understood. It is indeed not clear if hyperglycemia is directly implicated in cellular damage or just an associated epiphenomenon and a marker of high stress levels and adrenergic response.11,12 Another possible mechanism for the adverse effects of hyperglycemia could be alterations in intra-platelet signaling pathways contributing to the development of atherothrombotic complications in patients with ACS.13

In patients presenting with STEMI and hyperglycemia on-admission, in-hospital mortality was higher than in those with lower serum glucose levels regardless to the implementation of a reperfusion strategy. In acutely reperfused patients themselves, the prognostic impact of hyperglycemia was independent of reperfusion modality. This is in accordance with several other reports. In the old DIGAMI study, in patients managed with thrombolysis, hyperglycemia was associated with higher mortality rates.4 In the more recent HORIZONS-AMI trial,8 all patients were managed with primary PCI and hyperglycemia (serum glucose level ≥156 mg/dL) was associated with higher mortality rates from all and cardiac causes and higher incidence of reinfarction and bleeding.

In the present study, we tried to identify the influence of diabetic status on the prognostic value of hyperglycemia in patients presenting for STEMI. In this regard, the two main findings were: (i) in diabetics but not in non-diabetics, hyperglycemia was independently associated with in-hospital death in a multivariate model combining several classical death predictors in STEMI, (ii) the predictive value of hyperglycemia for in-hospital death assessed by the area under the ROC curve was higher in diabetic than in non-diabetic patients. Interestingly, these findings are not concordant with all available data.14, 15, 16 In a Japanese study,16 acute but not chronic hyperglycemia (defined on high glycated hemoglobin level) was associated with large infarct size and high in hospital mortality in patient with acute myocardial infarction. This fact could be explained by the presence in our population of other confounding factors that were not taken into account in the multivariable model, could be simply a marker of grater cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients presenting for STEMI in our context or simply by the small size of the population and the low incidence of adverse outcomes in non-diabetic patients.

4.1. Study limitations

Although highlighting the prognostic value of hyperglycemia on-admission in patients presenting for STEMI, several limitations for this study have to be signaled including its observational and retrospective character. No randomization could be performed mandating much caution in interpreting some results yielded by analyses especially those pertaining to reperfusion modalities. The higher predictive value of hyperglycemia for adverse outcomes in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic ones is not in accordance with other studies, but this could be simply due to the worse cardiovascular risk profile in these patients (especially in Tunisia) rather that a direct effect of higher glycemic levels in this particular group. Another limitation is that no specific therapeutic modality has been suggested for patients with worse outcomes according to the glycemic level. A randomized study is warranted to test such therapeutic interventions. Finally, statistical significance could not be reached in some sub-groups obviously due to either small size or the low incidence of the endpoint studied.

5. Conclusions

According to the current study, hyperglycemia has a substantial impact on in-hospital course in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. In diabetic patients particularly, hyperglycemia was independently predictive of in-hospital death. In diabetic patients, admission serum glucose level has a good predictive value for in-hospital death.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Steg P.G., James S.K., Atar D. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buntaine A.J., Shah B., Lorin J.D., Sedlis S.P. Revascularization strategies in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute Coronary syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(August (8)):79. doi: 10.1007/s11886-016-0756-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angeli F., Reboldi G., Poltronieri C. Hyperglycemia in acute coronary syndromes: from mechanisms to prognostic implications. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;9(December (6)):412–424. doi: 10.1177/1753944715594528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malmberg K., Norhammar A., Wedel H., Rydén L. Glycometabolic state at admission: important risk marker of mortality in conventionally treated patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction: long-term results from the Diabetes and Insulin-Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) study. Circulation. 1999;99(May (20)):2626–2632. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.20.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timmer J.R., Hoekstra M., Nijsten M.W. Prognostic value of admission glycosylated hemoglobin and glucose in nondiabetic patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2011;124(August (6)):704–711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), Wijns W. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501–2555. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stranders I., Diamant M., van Gelder R.E. Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(May (9)):982–988. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Planer D., Witzenbichler B., Guagliumi G. Impact of hyperglycemia in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(September (6)):2572–2579. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosiborod M., Inzucchi S.E., Krumholz H.M. Glucometrics in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: defining the optimal outcomes-based measure of risk. Circulation. 2008;117(February (8)):1018–1027. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angeli F., Verdecchia P., Karthikeyan G. New-onset hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome: a systematic overview and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6(March (2)):102–110. doi: 10.2174/157339910790909413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCowen K.C., Malhotra A., Bistrian B.R. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17(January (1)):107–124. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huberlant V., Preiser J.C. Year in review 2009: critical care–metabolism. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):238. doi: 10.1186/cc9256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferroni P., Basili S., Falco A., Davì G. Platelet activation in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(August (8)):1282–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capes S.E., Hunt D., Malmberg K., Gerstein H.C. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet. 2000;355(March (9206)):773–778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosiborod M., Rathore S.S., Inzucchi S.E. Admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: implications for patients with and without recognized diabetes. Circulation. 2005;111(June (23)):3078–3086. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujino M., Ishihara M., Honda S. Impact of acute and chronic hyperglycemia on in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(December (12)):1789–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]