Abstract

We present the case of a child with long-standing, super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE) who manifested prompt and complete resolution of SRSE upon exposure to pure cannabidiol. SRSE emerged in the context of remote suspected encephalitis with previously well-controlled epilepsy. We discuss the extent to which response may be specifically attributed to cannabidiol, with consideration and discussion of multiple potential drug–drug interactions. Based on this case, we propose that adjunctive cannabidiol be considered in the treatment of SRSE.

Keywords: EEG, Status epilepticus, Cannabidiol, Pediatric

Highlights

-

•

Adjunctive cannabidiol may be effective in the treatment of super refractory status epilepticus

1. Introduction

Super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE) is defined as status epilepticus that continues or recurs at least 24 h after the onset of anesthesia [1]. SRSE is an important focus of ongoing research given the exceptionally high morbidity and mortality [2], [3], and the absence of evidence-based therapeutic options. Given the relatively low incidence of SRSE, clinical trials are quite challenging from a feasibility standpoint. Accordingly, although there are no randomized controlled trials supporting any specific treatment modality, there are abundant contemporary case reports and case series suggesting effectiveness of multiple therapies including ketamine [4], ketogenic diet therapy [5], [6], electroconvulsive therapy [7], thalamic deep brain stimulation [8], repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation [9], surgical resection (even hemispherectomy) [10], [11], immunotherapy (i.e. corticosteroids) [12], and most recently, allopregnanolone [13], [14], [15].

The treatment of epilepsy with cannabis (marijuana) derivatives, and in particular cannabidiol (CBD), has generated great enthusiasm in recent years. Several contemporary studies suggest that adjunctive CBD is efficacious and well-tolerated in the setting of Dravet syndrome [16], Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome [17], and infantile spasms [18], and controlled clinical trials are either completed or underway for all three syndromes. However, there is no compelling evidence that the potential efficacy of CBD is limited to these relatively uncommon childhood-onset epilepsies. CBD may represent a broad-spectrum anti-seizure drug (ASD), given that (1) the precise anti-seizure mechanism of action of CBD is unknown, (2) the hypothesis that CBD impacts neuronal function via multiple – and perhaps novel – mechanisms [19], and (3) the observation that CBD bears little structural resemblance to all other ASDs. With regard to SRSE, there has been mixed success accompanying the use of CBD. Whereas an artisanal CBD-enriched extract was reported ineffective in the treatment of a single young adult with SRSE [20], efficacy of pharmaceutical-grade purified cannabidiol was favorable in a series of children treated for highly refractory seizures (including status epilepticus) attributed to febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) [21]. We now present the case of a child with SRSE (not associated with FIRES) treated with pharmaceutical-grade purified CBD.

2. Methods

Clinical data were abstracted from the medical record. The use of CBD (Epidiolex®, GW Pharmaceuticals, UK) was accomplished via the emergency investigational new drug (EIND) program of the United States Food and Drug Administration. Informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents prior to any study procedures.

3. Clinical history

The patient is a 12-year-old right-handed female with history of epilepsy of unknown cause (possible encephalitis), with onset at age 5 years. Seizures manifested with exclusively left-hemispheric onset focal seizures, with and without impairment of awareness, and with and without focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures. From age 5 to 12 years, long spans of seizure freedom accompanied the use of lacosamide (LAC), levetiracetam (LEV), and clobazam (CLB), though breakthrough seizures occurred approximately annually. At age 12, the patient suffered a precipitous and unexplained escalation of seizures, with evolution to SRSE. After numerous treatment failures (see Fig. 1), seizures were nearly controlled with intravenous midazolam (MDZ) or pentobarbital (PTB), though multiple attempts to wean either agent led to resurgence of seizures. With seizures localized to both the left central and frontopolar regions on EEG – despite normal neuroimaging – the clinical team prepared for extraoperative electrocorticography with the expectation that the identified epileptogenic zone would likely encompass dominant motor cortex (hand). Anticipated resection of eloquent cortex was deemed reasonable, relative to the risks of SRSE and prolonged intensive care unit hospitalization.

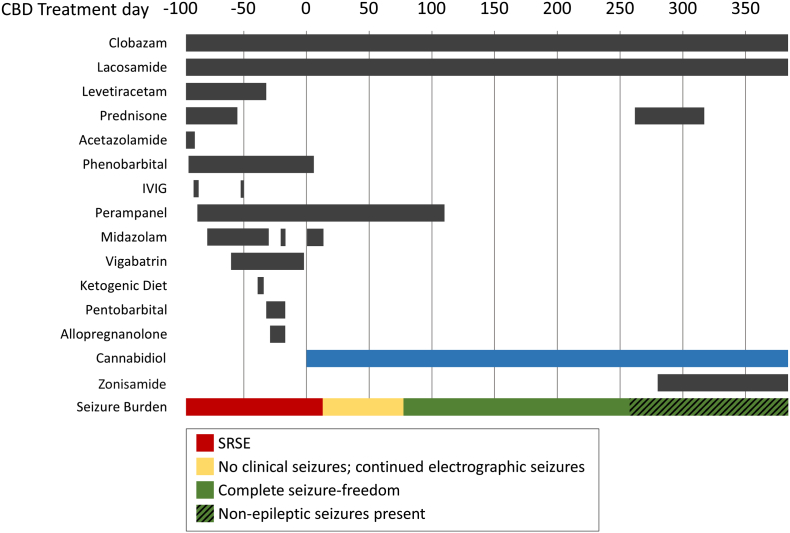

Fig. 1.

Time course of seizure burden and treatment exposure.

After three months of SRSE and numerous treatment failures, CBD treatment (blue) accompanied prompt resolution of seizures. On day 258, non-epileptic seizures emerged and were mistaken for epileptic seizures, prompting a course of prednisone (now discontinued) and zonisamide (now tapering off). Abbreviations: IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; SRSE, super-refractory status epilepticus.

After more than three months of SRSE, as a last medication trial prior to surgery, the patient began treatment with CBD in the midst of frequent clinical seizures (5–20/day) and while still receiving MDZ (0.3 mg/kg/h), CLB (1 mg/kg/day), phenobarbital (PB, 0.8 mg/kg/day), LAC (10 mg/kg/day), and perampanel (PER, 0.2 mg/kg/day). CBD was administered orally with an initial dosage of 5 mg/kg/day, divided BID, with titration by 5 mg/kg/day every 3 days to a peak dose of 20 mg/kg/day. Clinical seizure-freedom was achieved on day 12 of CBD, but subclinical seizures persisted. The patient was discharged on day 21 of CBD, and complete seizure freedom was demonstrated with 24-hour video-EEG on day 64 of CBD. The patient remains seizure-free at most recent follow-up, despite the sequential discontinuation of PB, MDZ, PER, and dose-reduction of LAC. At present, the patient is maintained on CBD (20 mg/kg/day), CLB (0.8 mg/kg/day), and zonisamide (ZNS) (0.6 mg/kg/day, tapering).

CBD was generally well-tolerated with the patient having resumed all activities of daily living, though she reported substantial fatigue and gained 15 kg (25% body mass) in the first year of CBD exposure. In addition she developed new-onset non-epileptic seizures (NES), which were initially mistaken for epileptic seizures and which prompted a course of corticosteroids, titration of CBD to the original weight-based dosage of 20 mg/kg/day, and initiation of ZNS.

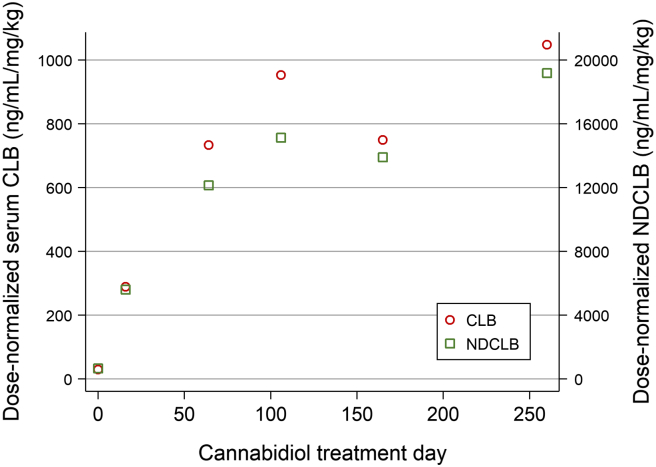

Of note, compared to pre-CBD baseline, serum levels of CLB and N-desmethylclobazam (NDCLB) rose substantially (Fig. 2) during both titration and maintenance of CBD treatment, and despite aforementioned reductions in the weight-based dosage of CBD and CLB. In addition, the relatively dramatic rise in CLB and NDCLB levels over the first 60 days of CBD therapy also accompanied discontinuation of PB and MDZ and dose-reduction of PER.

Fig. 2.

Clobazam and N-desmethylclobazam (NDCLB) levels as a function of cannabidiol exposure.

A dramatic non-linear rise in dose-normalized CLB and NDCLB levels accompanied CBD exposure. Maximum CBD dosage was achieved on day 10 and further elevations in serum CLB/NDCLB levels accompanied discontinuation of MDZ, PB, PER, and dose-reduction of LAC.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report in which adjunctive CBD treatment promptly accompanied resolution of SRSE not associated with FIRES. The favorable outcome in this patient is especially noteworthy given the considerable risk of morbidity that would have likely accompanied an even longer intensive care unit hospitalization, or the disability that might have accompanied the resection of eloquent cortex. However, as this was not a controlled trial, we must consider other potential – albeit unlikely – mediators of response, including spontaneous resolution of SRSE, a late effect of allopregnanolone, or perhaps elevated serum levels of CLB and NDCLB. Furthermore, to the extent that CBD may have been effective, it is unclear whether response should be attributed to CBD alone, or the combination of CBD with CLB, MDZ, LAC, and/or PB.

With regard to allopregnanolone, the likelihood of late response is small. In those cases in which allopregnanolone has been reported as successful, allopregnanolone enabled successful taper of first-line therapy for status epilepticus (e.g. PTB or MDZ) [13], [14], [15]. In our patient, PTB taper following allopregnanolone was unsuccessful. Furthermore, this patient required continuous PTB or MDZ infusion for 20 days following the last dose of allopregnanolone, a span during which CBD dosage was titrated.

The possibility of interaction – or perhaps synergy – between CBD and CLB is intriguing. The effect of CBD exposure on CLB and NDCLB levels is well-characterized. Given that CBD is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 [22] and CYP2C19 [23] – at least in vitro – and that both CLB and NDCLB are substrates of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 [24] it is not surprising that CLB and NDCLB concentrations rose. However, rather than a symmetric rise in CLB and NSCLB levels, we would have expected isolated NDCLB elevation, or NDCLB rise out of proportion to CLB, as observed in prior reports [25], [26], [27]. Furthermore, it is unclear why CLB and NDCLB levels continued to rise after CBD titration was complete. We suspect that a third- or higher-order drug–drug interaction may have occurred and speculate that dose reduction of PB (a CYP3A4 inducer) might have also yielded higher CLB and NDCLB concentrations. Conversely, CLB exposure may increase serum levels of both CBD and its active metabolite, 7-hydroxycannabidiol, via CYP2D6 and/or UGT inhibition, thus suggesting a bidirectional relationship [28]. From a clinical standpoint, however, it seems unlikely that the supratherapeutic levels of CLB and NDCLB that accompanied CBD treatment are responsible for resolution of SRSE. With the observation that our patient was conscious in spite of long-standing and high doses of MDZ (0.3 mg/kg/h) and CLB (1 mg/kg/day), we postulate that synaptic GABAA receptors were likely internalized to a large extent, and thus inaccessible targets of CLB and NDCLB at the time CBD were initiated.

5. Conclusion

Given the paucity of evidence-based therapies for SRSE as well as the prompt and enduring response that accompanied the adjunctive administration of CBD in this patient, CBD should be a consideration in the treatment of SRSE. However, this report does not prove efficacy and pharmacokinetic analysis in the setting of SRSE is needed to disentangle possible drug–drug interactions. A formal clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CBD for treatment of SRSE is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This study was accomplished with support from the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children's Discovery and Innovation Institute.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Rajaraman declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. Sankar serves on scientific advisory boards for and has received honoraria and funding for travel from Eisai, UCB Pharma, Sunovion, and Lundbeck Pharma; receives royalties from the publication of Pediatric Neurology, 4th ed. (Demos Publishing, 2017) and Epilepsy: Mechanisms, Models, and Translational Perspectives (CRC Press, 2011); serves on speakers' bureaus for and has received speaker honoraria from Eisai, UCB, and Lundbeck. He has received research support from Insys Development Company, Inc., and honoraria for service on an Insys scientific advisory board.

Dr. Hussain has received research support from the Epilepsy Therapy Project, the Milken Family Foundation, the Hughes Family Foundation, the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, Eisai, Lundbeck, UCB, Insys, GW Pharmaceuticals, and the NIH (R34MH089299). He has received honoraria for service on the scientific advisory boards of Mallinckrodt, Upsher-Smith, Insys, and UCB; as a consultant to UCB, Upsher-Smith and Mallinckrodt; and on the speaker's bureau for Mallinckrodt.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Shorvon S. Super-refractory status epilepticus: an approach to therapy in this difficult clinical situation. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl. 8):53–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlisi M., Shorvon S. The outcome of therapies in refractory and super-refractory convulsive status epilepticus and recommendations for therapy. Brain J Neurol. 2012;135:2314–2328. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chateauneuf A.-L., Moyer J.-D., Jacq G., Cavelot S., Bedos J.-P., Legriel S. Super-refractory status epilepticus: epidemiology, early predictors, and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1532–1534. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosati A., L'Erario M., Ilvento L., Cecchi C., Pisano T., Mirabile L. Efficacy and safety of ketamine in refractory status epilepticus in children. Neurology. 2012;79:2355–2358. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278b685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farias-Moeller R., Bartolini L., Pasupuleti A., Brittany Cines R.D., Kao A., Carpenter J.L. A practical approach to ketogenic diet in the pediatric intensive care unit for super-refractory status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2017;26:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cobo N.H., Sankar R., Murata K.K., Sewak S.L., Kezele M.A., Matsumoto J.H. The ketogenic diet as broad-spectrum treatment for super-refractory pediatric status epilepticus: challenges in implementation in the pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:259–266. doi: 10.1177/0883073813516192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed J., Metrick M., Gilbert A., Glasson A., Singh R., Ambrous W. Electroconvulsive therapy for super refractory status epilepticus. J ECT. 2017 doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehtimäki K., Långsjö J.W., Ollikainen J., Heinonen H., Möttönen T., Tähtinen T. Successful management of super-refractory status epilepticus with thalamic deep brain stimulation. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:142–146. doi: 10.1002/ana.24821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thordstein M., Constantinescu R. Possibly lifesaving, noninvasive, EEG-guided neuromodulation in anesthesia-refractory partial status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;25:468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh S., Mathern G.W., Glasser G., Wu J.Y., Shields W.D., Jonas R. Status epilepticus and frequent seizures: incidence and clinical characteristics in pediatric epilepsy surgery patients. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1950–1954. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak R., Mathew V., Rajgopal R., Raju K. Hemispherotomy for late post-traumatic super-refractory status epilepticus in an adult. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2017;8:114–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravljanac R., Djuric M., Jankovic B., Pekmezovic T. Etiology, clinical course and response to the treatment of status epilepticus in children: a 16-year single-center experience based on 602 episodes of status epilepticus. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19:584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broomall E., Natale J.E., Grimason M., Goldstein J., Smith C.M., Chang C. Pediatric super-refractory status epilepticus treated with allopregnanolone. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:911–915. doi: 10.1002/ana.24295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaitkevicius H., Husain A.M., Rosenthal E.S., Rosand J., Bobb W., Reddy K. First-in-man allopregnanolone use in super-refractory status epilepticus. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4:411–414. doi: 10.1002/acn3.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal E.S., Claassen J., Wainwright M.S., Husain A.M., Vaitkevicius H., Raines S. Brexanolone as adjunctive therapy in super-refractory status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:342–352. doi: 10.1002/ana.25008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devinsky O., Cross J.H., Laux L., Marsh E., Miller I., Nabbout R. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2011–2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiele E.A., Marsh E.D., French J.A., Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M., Benbadis S.R., Joshi C. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain S.A., Zhou R., Jacobson C., Weng J., Cheng E., Lay J. Perceived efficacy of cannabidiol-enriched cannabis extracts for treatment of pediatric epilepsy: a potential role for infantile spasms and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;47:138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibeas Bih C., Chen T., Nunn A.V.W., Bazelot M., Dallas M., Whalley B.J. Molecular targets of cannabidiol in neurological disorders. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2015;12:699–730. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosemergy I., Adler J., Psirides A. Cannabidiol oil in the treatment of super refractory status epilepticus. A case report. Seizure. 2016;35:56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gofshteyn J.S., Wilfong A., Devinsky O., Bluvstein J., Charuta J., Ciliberto M.A. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) in the acute and chronic phases. J Child Neurol. 2017;32:35–40. doi: 10.1177/0883073816669450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaori S., Ebisawa J., Okushima Y., Yamamoto I., Watanabe K. Potent inhibition of human cytochrome P450 3A isoforms by cannabidiol: role of phenolic hydroxyl groups in the resorcinol moiety. Life Sci. 2011;88:730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang R., Yamaori S., Okamoto Y., Yamamoto I., Watanabe K. Cannabidiol is a potent inhibitor of the catalytic activity of cytochrome P450 2C19. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28:332–338. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-12-rg-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giraud C., Tran A., Rey E., Vincent J., Tréluyer J.-M., Pons G. In vitro characterization of clobazam metabolism by recombinant cytochrome P450 enzymes: importance of CYP2C19. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:1279–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geffrey A.L., Pollack S.F., Bruno P.L., Thiele E.A. Drug–drug interaction between clobazam and cannabidiol in children with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1246–1251. doi: 10.1111/epi.13060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaston T.E., Bebin E.M., Cutter G.R., Liu Y., Szaflarski J.P., UAB CBD Program Interactions between cannabidiol and commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1586–1592. doi: 10.1111/epi.13852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devinsky O., Patel A.D., Thiele E.A., Wong M.H., Appleton R., Harden C.L. Randomized, dose-ranging safety trial of cannabidiol in Dravet syndrome. Neurology. 2018;90:e1204–e1211. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommerville K., Crockett J. Bidirectional drug–drug interaction with coadministration of cannabidiol and clobazam in a phase 1 healthy volunteer trial. Annu Meet Am Epilepsy Soc. 2017:1–433. [Google Scholar]