Abstract

A 56-year-old Japanese woman with muscle weakness, increased creatine kinase and aldolase levels, and characteristic cutaneous lesions was diagnosed with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody (anti-MDA5 antibody)-positive dermatomyositis. She also had interstitial lung disease (ILD). After corticosteroid and tacrolimus combination therapy was started, bicytopenia and elevated serum ferritin and transaminase emerged. Because the bone marrow tissues were hypoplastic with hemophagocytes, she was diagnosed with concomitant autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS). Intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy and plasmapheresis were performed. The laboratory findings indicated improved abnormalities, and the ILD did not progress. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis can be complicated by HPS.

Keywords: anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis, autoimmune disease, hemophagocytic syndrome, corticosteroid therapy, cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis

Introduction

Dermatomyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by distinct cutaneous involvement with typical lesions (1). A particular type of dermatomyositis presents with rapidly progressive interstitial lung diseases (RP-ILDs) resulting in fatal outcomes. The anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5) antibody is associated with dermatomyositis with RP-ILD and is resistant to treatment (2). There have been some reports that patients with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis have elevated levels of serum ferritin (3), and serum ferritin might be associated with the disease activity of ILDs in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis (4).

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is a life-threatening syndrome characterized by clinical signs and symptoms of intense immune activation, which consist of a fever, cytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and hyperferritinemia (5). Infections, autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases, malignancies, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome can cause HPS (6). With regard to autoimmune diseases, adult Still's disease and systemic lupus erythematosus are sometimes complicated by HPS.

In clinical practice, the presence of hyperferritinemia in rheumatic diseases may suggest complications of HPS associated with rheumatic diseases. However, we sometimes cannot determine whether patients with dermatomyositis with positive anti-MDA5 antibody who have hyperferritinemia have HPS as well. The diagnosis of HPS is pivotal in patients with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis because HPS sometimes requires additional treatment. In patients who show resistance to immunosuppuressive therapy, we can administer plasmapheresis.

We herein report a case of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by HPS that was treated with immunosuppressive therapy and plasmapheresis.

Case Report

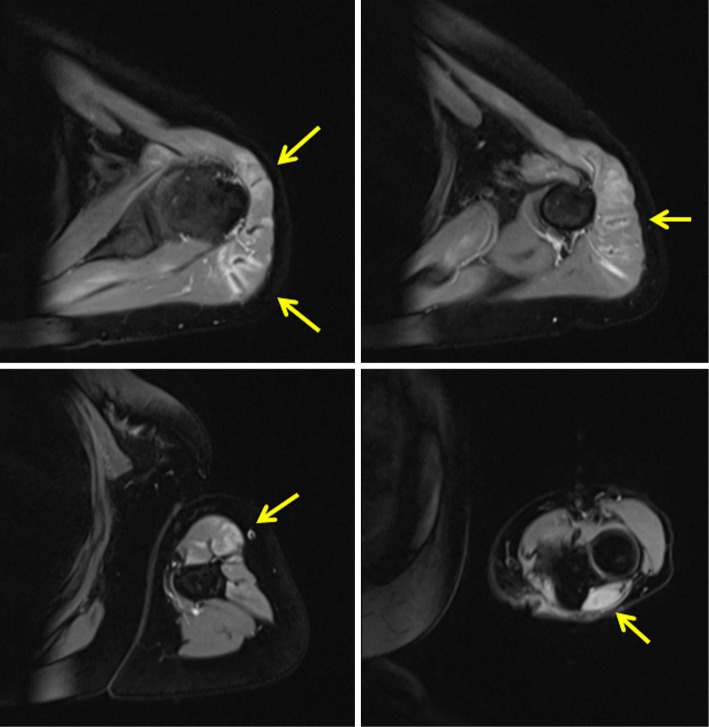

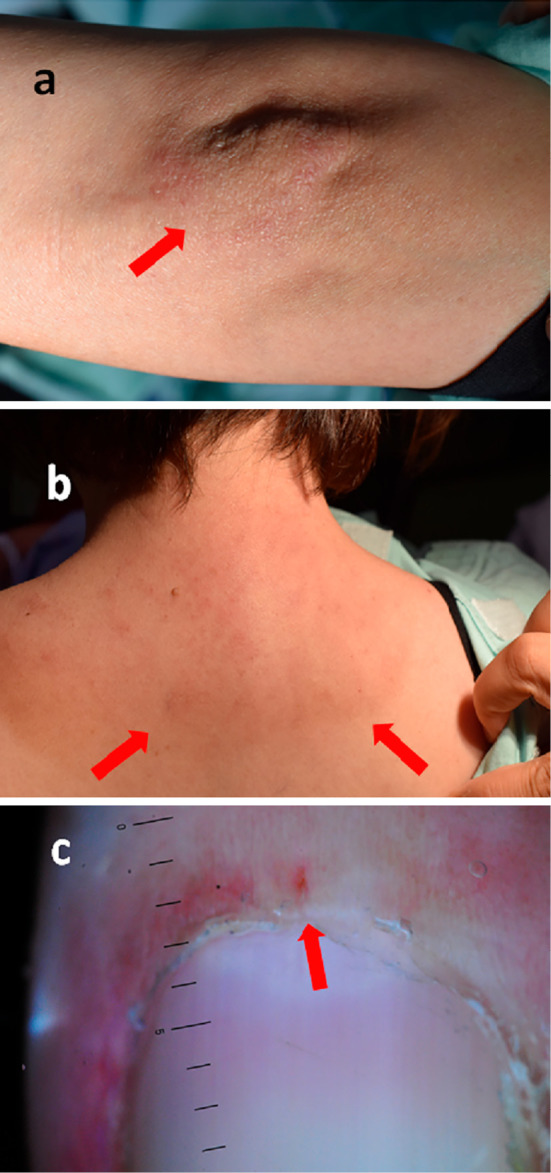

A 56-year-old woman was transferred to our hospital with muscle weakness, myalgia, and thrombocytopenia from another hospital. Two months prior to this admission, the patient presented with a fever, muscle weakness, myalgia, and eruption. She was then admitted to another hospital a month before this admission. She had heliotrope rash, shawl sign, Gottron's sign on the dorsum of hands and elbow, periungual erythema, and nailfold bleeding (Fig. 1) and was diagnosed by her previous physician with dermatomyositis, based on the typical cutaneous lesions, proximal muscle weakness, and elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) levels. Her serum was positive for anti-MDA5 antibody. Chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated mild ILD in the bilateral lung. She was treated with 40 mg/day of oral prednisolone following pulsed methylprednisolone therapy (1,000 mg/day for 3 consecutive days per week) and oral tacrolimus. Although the cutaneous lesions improved, thrombocytopenia emerged, and the serum ferritin level increased. She was then transferred to our hospital for stronger treatments.

Figure 1.

Cutaneous involvement at the diagnosis. (a) Gottron’s sign on the left elbow (arrow). (b) Shawl sign around the neck (arrows). (c) Microvascular abnormality in nailfold (arrow).

On admission, a physical examination revealed the following: body temperature, 36.3℃; blood pressure, 119/90 mmHg; pulse rate, 92/min. Auscultation of the chest showed neither heart murmur nor crackles. Gottron's sign on her bilateral elbows, periungual erythema, and bilateral proximal muscle weakness were still present. The peripheral blood cell count and biochemistry revealed the following: white blood cell count, 3,000/μL (neutrophils, 60.1%; lymphocytes, 27.9%; monocytes, 12%; eosinophils 0%; basophils, 0%); hemoglobin, 15.1 g/dL; platelet count, 74,000/μL; C-reactive protein, 0.02 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 6 mm/h; lactate dehydrogenase, 710 IU/L (reference range, 124-222 IU/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 1,439 IU/L (reference range, 13-30 IU/L); alanine aminotransferase, 1,435 IU/L (reference range, 7-23 IU/L); alkaline phosphatase, 544 IU/L (reference range, 106-322 IU/L); γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 1,058 IU/L (reference range, 9-32 IU/L); CK, 746 IU/L (reference range, 41-153 IU/L); aldolase (ALD), 56.4 IU/L (reference range, 2.1-6.1 IU/L); blood urea nitrogen, 17 mg/dL (reference range, 8.0-22.0 mg/dL); serum creatinine, 0.39 mg/dL (reference range, 0.47-0.79 mg/dL); Krebs von den Lungen (KL)-6, 830 U/mL (reference range, 105.3-401 U/mL); and soluble interleukin-2 receptor, 599 IU/L (reference range, 122-496 IU/mL). The serum ferritin was increased at 5,953 ng/mL. A cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia (C7-HRP) analysis was negative. A connective tissue workup showed an antinuclear antibody titer, 1:80 (nucleolar pattern); elevated anti-MDA5 antibody, ≥150 index [reference values, <32 index, anti-MDA5 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (MESACUP anti-MDA5 test; Medical & Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan)]. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed extensive T2 short-tau inversion recovery (STIR)-hyperintense lesions and enhancement in the muscles of her left upper arm (Fig. 2). Chest CT showed consolidation in the dorsal side of bilateral lungs and near the pleura, which suggested ILD (Fig. 3a).

Figure 2.

MRI findings on admission: left upper arm. T2-weighted STIR imaging showed hyperintensity in the muscle (arrows). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, STIR: short-tau inversion recovery

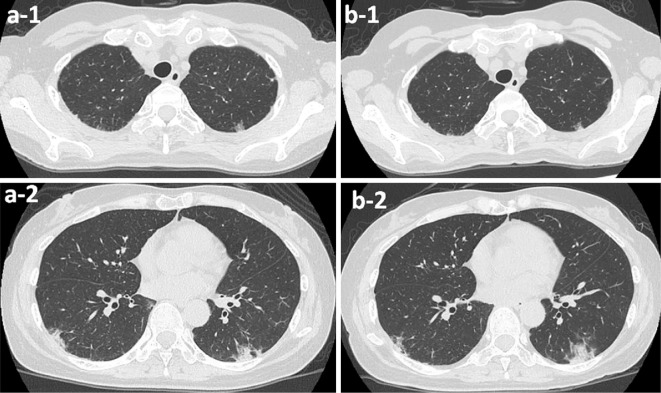

Figure 3.

(a) Chest computed tomography (CT) findings on admission: (a-1) ground glass opacity in the bilateral upper lobes of lungs; (a-2) Consolidations along the bronchi in the bilateral dorsal lungs. (b-1 and b-2) Chest CT findings did not show any worsening until her discharge.

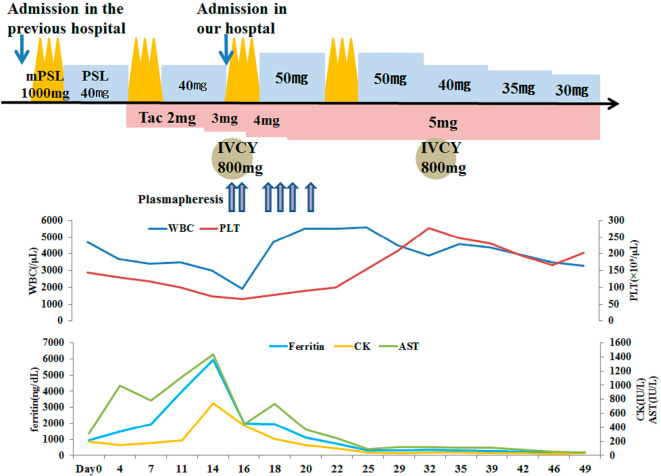

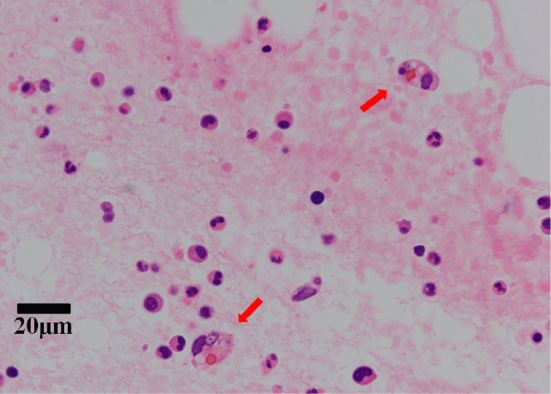

Based on the bilateral proximal muscle weakness, increased CK and ALD levels, and characteristic cutaneous lesions, we diagnosed her with dermatomyositis complicated by ILD. On comparing the most recent CT findings with those of the previous hospital, her ILD had not worsened. Because the laboratory tests showed bicytopenia, elevated transaminase, and elevated ferritin, we suspected complications of HPS. Therefore, we promptly conducted bone marrow aspiration to evaluate the cause of bicytopenia. Considering the probability of RP-ILD and HPS, we added pulsed methylprednisolone therapy, monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy [IVCY; 800 mg (=15 mg/kg)] and increased oral tacrolimus from 2 mg to 3 mg on the day of admission to our hospital. Bone marrow tissues demonstrated hypoplastic marrow with hemophagocytes. Because of the bicytopenia in the peripheral blood and the pathological finding of histiocytic hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow (Fig. 4) under the active status of an underlying autoimmune disease, we diagnosed her with autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (AAHS) based on the diagnostic criteria for AAHS proposed by Kumakura et al. (7). We ruled out infections and malignancy that could cause HPS. Because the combination therapy of prednisolone and tacrolimus was insufficient for AAHS and we could not expect the prompt effectiveness of IVCY, we added plasmapheresis. Plasmapheresis was performed six times for 9 days. The plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive therapy were effective, and the muscle weakness improved gradually. Laboratory results showed improved platelet, liver enzyme, and ferritin levels (Fig. 5), and the ILD did not progress (Fig. 3b). We continue to treat with regular IVCY.

Figure 4.

Pathological findings in the bone marrow. The bone marrow was hypoplastic and contained hemophagocytosis (arrows). No atypical cells were noted.

Figure 5.

The clinical course of this 56-year-old woman. mPSL pulse: pulsed methylprednisolone, PSL: prednisolone, IVCY: intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy, Tac: tacrolimus, WBC: white blood cell, PLT: platelet, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, CK: creatine kinase

Discussion

We described the case of a patient with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by AAHS. To our knowledge, there have been no reports of the successful treatment of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by AAHS as confirmed by bone marrow aspiration findings. We successfully treated the present with aggressive immunosuppressive therapy for her dermatomyositis and plasmapheresis for her AAHS.

Only 6.9% of AAHS cases are caused by dermatomyositis (8). However, in the report of Yajima et al. (9), of the 24 patients with dermatomyositis, 4 had concomitant HPS, including 1 with amyopathic dermatomyositis. In their study, the patient with HPS was positive for anti Jo-1 antibody, but the authors did not mention other types of autoantibodies, such as anti-MDA5 antibody. They also mentioned that HPS complicated by dermatomyositis required aggressive immunosuppressive therapy using a combination of glucocorticoids and immunosuppression with intravenous immunoglobulin. Furthermore, when immunosuppressive therapy is insufficient for AAHS, plasmapheresis is sometimes reported to be effective for AAHS with other rheumatic diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and adult Still's disease (10-12). Our case also required plasmapheresis, as AAHS emerged despite her previously undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.

In the present case, hyperferritinemia with bicytopenia and elevated transaminase suggested AAHS as a complication. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis alone was unable to explain the bicytopenia in our patient. The serum ferritin level is increased in cases of HPS with concomitant AAHS (13). Other major laboratory findings in AAHS are anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and elevated transaminase (14). Although serum ferritin is sometimes associated with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis (3,4), hyperferritinemia in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis may be caused by concomitant AAHS. It is vital not to overlook concomitant AAHS in findings associated with hyperferritinemia.

The combination therapy of corticosteroids, IVCY, and a calcineurin inhibitor, such as cyclosporin A or tacrolimus, is required because anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis with ILD is sometimes fatal (15). In our case, her ILD did not rapidly progress after the treatments. Silveira et al. (16) reported a case of rapidly progressing ILD with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis that was unresponsive to aggressive immunosuppressive therapy but was eventually successfully treated with plasmapheresis and hemoperfusion with polymyxin B. However, whether or not plasmapheresis affected the clinical course of ILD in our case remains unknown.

In conclusion, we encountered a patient with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by AAHS whom we treated successfully with plasmapheresis in addition to immunosuppressants. Hyperferritinemia is an essential marker for anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis, but whether or not AAHS is the cause of the hyperferritinemia and cytopenia must be determined before adding plasmapheresis as a treatment, which may result in a favorable outcome.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Iaccarino L, Ghirardello A, Bettio S, et al. . The clinical features, diagnosis and classification of dermatomyositis. J Autoimmun 48-49: 122-127, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, et al. . Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 52: 1571-1576, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakashima R, Imura Y, Kobayashi S, et al. . The RIG-I-like receptor IFIH1/MDA5 is a dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen identified by the anti-CADM-140 antibody. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49: 433-440, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Ozeki E, et al. . Serum ferritin correlates with activity of anti-MDA5 antibody-associated acute interstitial lung disease as a complication of dermatomyositis. Mod Rheumatol 21: 223-227, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. . Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood 127: 2672-2681, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes-an update. Blood Rev 28: 135-142, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumakura S, Ishikura H, Kondo M, Murakawa Y, Masuda J, Kobayashi S. Autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Mod Rheumatol 14: 205-215, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumakura S, Murakawa Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in adults. Arthritis Rheumatol 66: 2297-2307, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yajima N, Wakabayashi K, Odai T, et al. . Clinical features of hemophagocytic syndrome in patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 35: 1838-1841, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banno S, Sugiura Y, Yoshinouchi T, Matsumoto Y, Ueda R. Successful treatment of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome by plasmapheresis and high-dose gamma-globulin in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol 10: 263-266, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsumoto Y, Naniwa D, Banno S, Sugiura Y. The efficacy of therapeutic plasmapheresis for the treatment of fatal hemophagocytic syndrome: two case reports. Ther Apher 2: 300-304, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Komiya Y, Takenaka K, Nagasaka K. Successful treatment of glucocorticoid and cyclosporine refractory adult-onset Still's disease complicated with hemophagocytic syndrome with plasma exchange therapy and tocilizumab : a case report. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi 36: 478-483, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, Filipovich AH, McClain KL. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 118: 4041-4052, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 383: 1503-1516, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kameda H, Nagasawa H, Ogawa H, et al. . Combination therapy with corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide for acute/subacute interstitial pneumonia in patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 32: 1719-1726, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silveira MG, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Ramos-Terrades N, Arredondo-Agudelo KV, Labrador-Horrillo M, Bravo-Masgoret C. Anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis and progressive interstitial pneumonia. QJM 109: 49-50, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]