Abstract

Background

The epidemiology and burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) illness are not well defined in older adults.

Methods

Adults ≥60 years old seeking outpatient care for acute respiratory illness were recruited from 2004–2005 through 2015–2016 during the winter seasons. RSV was identified from respiratory swabs by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Clinical characteristics and outcomes were ascertained by interview and medical record abstraction. The incidence of medically attended RSV was estimated for each seasonal cohort.

Results

RSV was identified in 243 (11%) of 2257 enrollments (241 of 1832 individuals), including 121 RSV type A and 122 RSV type B. The RSV clinical outcome was serious in 47 (19%), moderate in 155 (64%), and mild in 41 (17%). Serious outcomes included hospital admission (n = 29), emergency department visit (n = 13), and pneumonia (n = 23) and were associated with lower respiratory tract symptoms during the enrollment visit. Moderate outcomes included receipt of a new antibiotic prescription (n = 144; 59%), bronchodilator/nebulizer (n = 45; 19%), or systemic corticosteroids (n = 28; 12%). The relative risk of a serious outcome was significantly increased in persons aged ≥75 years (vs 60–64 years) and in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure. The average seasonal incidence was 139 cases/10 000, and it was significantly higher in persons with cardiopulmonary disease compared with others (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% confidence interval, 1.44–2.48).

Conclusions

RSV causes substantial outpatient illness with lower respiratory tract involvement. Serious outcomes are common in older patients and those with cardiopulmonary disease.

Keywords: adult, epidemiology, incidence, outcomes, RSV

Over the past decade, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection has been increasingly recognized as an important cause of acute respiratory illness in older adults. Both influenza and RSV account for a substantial number of respiratory illness deaths among adults ≥65 years of age in the United States. From 1997 to 2009, influenza and RSV contributed to approximately 28 000 and 17 000 annual cardiorespiratory deaths, respectively [1]. RSV is also an important cause of adult respiratory illness in both developed and developing countries, including tropical and subtropical regions [2–4]. Studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s first identified RSV as a cause of acute respiratory illness in a variety of adult populations, including older adults, working-age adults, hospitalized patients, and residents of long-term care facilities [5–9]. Immunocompromised adults and those with advanced age and/or cardiopulmonary disease are at especially high risk for severe complications from RSV infection [10–14].

The incidence and burden of RSV in adults are difficult to measure as clinical symptoms are nonspecific and physician awareness of RSV in adults is limited. Most adult studies of RSV have been conducted in the hospital setting, where RSV accounts for about 4% to 12% of respiratory illness hospitalizations during the winter season [14–17]. Advanced age, radiographic pneumonia, ventilator support, and secondary bacterial infection are all associated with increased risk of death among hospitalized patients with RSV [18].

Few studies have assessed the incidence and clinical characteristics of adult RSV infections in the community and outpatient setting. A seminal prospective cohort study of adults ≥65 years of age during 4 winter seasons (1999–2003) found that 3%–7% developed symptomatic RSV infection each season [14]. A 6-season study of adults ≥50 years old with predominantly outpatient acute respiratory illness found that RSV was the third most common viral pathogen (after influenza and human rhinovirus) [19]. Advanced age, cough, nasal congestion, wheezing, and increasing interval from symptom onset to care-seeking were independently associated with RSV detection. The latter study was conducted in a Wisconsin community cohort, and the overall seasonal incidence of medically attended RSV illness was estimated as 154 episodes per 10 000 individuals ≥50 years old [20]. The incidence of medically attended RSV increased with age, and it was highest (199 episodes per 10 000) among persons ≥70 years of age.

RSV vaccines and antivirals for older adults are currently in prelicensure clinical trials [21], and more detailed knowledge of RSV incidence and burden is needed to inform policy recommendations and evaluate cost-effectiveness. The objective of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics, severity, clinical outcomes, and long-term incidence of medically attended RSV illness in a community cohort of adults ≥60 years of age from the 2004–2005 through 2015–2016 influenza seasons. This analysis significantly extends a previous report on medically attended RSV infections in adults ≥50 years of age in the community cohort from 2004–2005 through 2009–2010 [19]. The current report includes an additional 6 seasons with more detailed clinical information based on medical record abstraction for RSV cases, including physical exam findings, management, and outcomes.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

The Marshfield Clinic Research Institute conducted prospective seasonal studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness in a Wisconsin community cohort during the 2004–2005 through 2015–2016 seasons [22–25]. Before each influenza season, a community cohort was defined based on residency in or near Marshfield, Wisconsin, and receipt of care from the Marshfield Clinic. Individuals in the community cohort were eligible to be recruited when seeking care for acute respiratory illness in outpatient clinics (all seasons) or in the hospital setting (2004–2005 through 2009–2010). Each season, recruitment began when influenza activity was detected in the community and usually continued for 12–15 weeks. Symptom eligibility criteria varied by season but included fever/feverishness or cough during most seasons. For the 2011–2012 through 2015–2016 seasons, eligibility was based on the presence of acute respiratory illness with cough. The maximum duration of illness was 10 days for the 2004–2005 through 2006–2007 seasons and 7 days for all subsequent seasons. After obtaining informed consent, a midturbinate swab was obtained for influenza detection. Symptoms and onset date were assessed during the enrollment interview. Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed each season to identify influenza cases. After testing was complete, aliquots of samples in viral transport media were frozen at –80°C.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Marshfield Clinic Institutional Review Board. During each season, all study participants (or parents) provided informed consent for influenza testing. Multiplex RT-PCR testing to detect additional viruses was subsequently approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent.

Laboratory

Archived samples were tested for the presence of respiratory virus nucleic acid using a multiplex respiratory virus panel (GenMark Dx eSensor, Respiratory Viral Panel). This is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved multiplex panel for detection of RSV A and B, human rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza viruses 1–3, influenza A (H3, H1, and H1N1pdm09), influenza B, and adenoviruses B/E and C. Nucleic acid was extracted from the swabs using the Roche MagnaPure 2.0 system and was then amplified using RT-PCR with target-specific primers. Target-specific signals were determined by voltammetry, a process that generates electrical signals from ferrocene-labeled signal probes. A published comparison of 4 respiratory virus panels found that the GenMark Dx eSensor assay had 100% sensitivity for RSV A and RSV B detection [26].

Samples collected from the 2004–2005 through 2009–2010 seasons were previously tested using the GenMark multiplex assay in a separate study of RSV illness in adults ≥50 years of age [19]. A subset of these was retested in 2016 for validation as the original testing was performed before FDA licensure of the GenMark Dx eSensor assay. All samples collected from 2009–2010 through 2015–2016 were tested using the FDA-approved GenMark assay. For the 2014–2015 season only, funding for multiplex testing of respiratory swabs was provided by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Medical Record Abstraction

Electronic diagnosis codes, procedure codes, laboratory tests, and prescribing data were extracted from the medical record for all RSV-positive patients. Trained research coordinators abstracted detailed clinical data for the initial respiratory illness visit, subsequent outpatient or ED visits, and hospital admissions within 28 days for all participants with PCR-confirmed RSV illness. Symptoms of acute respiratory illness and onset date were available from the original study enrollment interview. Abstracted clinical data included additional symptoms not assessed during study enrollment, functional status, smoking status, physical exam findings, treatment, pulmonary function, and presence of specific comorbid chronic diseases. For each clinical encounter in the 28-day window, information was abstracted regarding diagnosis or suspicion of pneumonia, acute sinusitis, and acute otitis media.

Abstraction of laboratory results included hemoglobin, total leukocyte count, BUN, creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin A1c, procalcitonin, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Measures of cardiac and pulmonary function were abstracted, including peak flow, FEV1/FVC, oxygen saturation, and cardiac ejection fraction (from echocardiogram). Additional abstractions were performed for participants who were hospitalized within 28 days after PCR-confirmed RSV illness. Abstracted data included admission and discharge diagnoses, hospital course, use of supplemental oxygen or ventilation support, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, antibiotic or antiviral treatment, and disposition at discharge.

All chest x-ray and chest computed tomography (CT) reports for participants with RT-PCR-confirmed RSV illness were independently reviewed by 2 physicians to identify a new radiographic opacity or infiltrate within 28 days after enrollment. Chest x-rays obtained >48 hours after hospital admission were excluded as they may represent nosocomial rather than community-acquired illness. Discrepancies in x-ray interpretation were adjudicated by consensus. For the purposes of this analysis, pneumonia was defined as an illness meeting all of the following criteria: (1) clinical diagnosis or suspicion of pneumonia mentioned in the medical record; (2) new opacity or infiltrate identified by chest x-ray or CT scan; and (3) antimicrobial treatment.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes for RT-PCR-confirmed RSV illness were classified as serious, moderate, or mild. A serious outcome was defined as acute care hospital admission, emergency department (ED) visit for acute illness, or pneumonia occurring within 28 days after enrollment. A moderate outcome was defined as new antibiotic or antiviral therapy, new/increased bronchodilator therapy, or new/increased systemic corticosteroid therapy during the 28-day window after enrollment. Individuals were classified as having a mild outcome if they did not meet criteria for serious or moderate RSV illness outcome. A physician independently validated all serious clinical outcomes. Hospital admissions were reclassified to a nonserious outcome category if the reason for admission was unrelated to cardiopulmonary disease based on review of hospital records.

Analytic Approach

At the time of initial presentation, participants with RT-PCR-confirmed RSV were classified as having moderate to severe lower respiratory tract disease (RSV-msLRTD) if at least 3 of the following lower respiratory tract symptoms or signs were present: cough, wheezing (or worsening in baseline wheezing), new sputum production (or increase in baseline sputum), new (or worsening) shortness of breath, and tachypnea (≥20 breaths/minute). The same criteria were used to define RSV-msLRTD in a phase III clinical trial for RSV vaccine in older adults (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02608502).

For this descriptive analysis, we compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants ≥60 years of age with and without RT-PCR-confirmed RSV illness. Among those with RT-PCR-confirmed RSV illness, we further assessed clinical and demographic characteristics and severity stratified by RSV subtype (A or B), as well as presence or absence of RSV-msLRTD during the initial clinical encounter. Univariate comparisons were performed with the chi-square (categorical variables) or Wilcoxon test (continuous variables), as appropriate; P values of <.05 were considered significant.

Seasonal incidence of medically attended RSV illness was estimated in the community cohort for individuals ≥60 years of age for the period 2006–2007 through 2015–2016. Seasonal incidence is reported as episodes of medically attended RSV illness per 10 000 population. A detailed description of the incidence estimation procedure was published previously [27]. Briefly, all estimates were standardized to a 31-week period from approximately early October through early May using Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene surveillance data. Incidence calculations were based on 2 assumptions: (1) test results from enrolled patients can be extrapolated to nonenrolled cohort members with a respiratory illness visit during the enrollment period; and (2) the number of RSV cases occurring outside the enrollment period in the cohort was proportional to the number of statewide cases occurring outside the enrollment period. Poisson regression with analytic weights, offsets, and robust variance estimation was used to estimate seasonal incidence with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and test for linear trends in seasonal incidence. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

RSV was detected in 243 (11%) of 2257 encounters (representing 241 of 1832 individuals) for acute respiratory illness. RSV cases were equally represented by RSV A (n = 121) and RSV B (n = 122). Of the 243 RSV cases, 23 (9%) had an additional viral target identified. Influenza was detected in 519 (23%), and 5 (<1%) were positive for both RSV and influenza. There were 2 individuals with an episode of RSV during 2 different seasons; none of the study participants had 2 RSV episodes in the same season. Among 1495 encounters negative for RSV and influenza by RT-PCR, the most common viral pathogens were coronavirus OC43, NL63, HKU1, 229E (n = 210; 14%), human metapneumovirus (n = 184; 12%), human rhinovirus (n = 135; 9%), and parainfluenza virus types 1–4 (n = 74; 5%); 873 (39%) encounters were negative for all viral targets in the multiplex RT-PCR assay.

Patients with RT-PCR-confirmed RSV were similar to those with non-RSV respiratory illness in terms of age, gender, number of ED visits, and hospital admissions in the prior 12 months (Table 1). The mean (median) interval from symptom onset to study enrollment and swab collection was 4.0 (4.0) days for RSV-negative patients and 4.4 (4.0) days for RSV-positive patients (P = .006). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was present in 15% of those with RSV illness, 18% of those with other viral respiratory infection, and 27% of those with no virus detected. RSV prevalence among adults with acute respiratory illness varied from a low of 5% in 2004–2005 to a high of near 18% in 2005–2006 and 2011–2012. Both RSV A and B were detected in every season. Type A accounted for the majority of RSV-positive detections in 5 seasons, and type B in 4 seasons. In 3 seasons (2007–2008, 2010–2011, 2012–2013), the numbers of RSV A and B cases were approximately equal.

Table 1.

Characteristics of RSV-Positive and RSV-Negative Patients ≥60 Years of Age With Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness, 2004–2005 Through 2015–2016

| All Respiratory Illness | RSV Illness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All RSV-Positive (n = 243), No. (%) | All Non-RSV (n = 2014), No. (%) |

P | RSV A (n = 121), No. (%) |

RSV B (n = 122), No. (%) |

P | |

| Age at enrollment, mean (SD), y | 72.2 (8.7) | 71.5 (8.4) | .2 | 72.1 (8.6) | 72.3 (8.8) | .8 |

| Age group, y | .8 | .8 | ||||

| 60–64 | 55 (23) | 495 (25) | 27 (22) | 28 (23) | ||

| 65–74 | 101 (42) | 836 (42) | 53 (44) | 48 (39) | ||

| 75+ | 87 (36) | 683 (34) | 41 (34) | 46 (38) | ||

| Gender | .1 | .5 | ||||

| Male | 85 (35) | 805 (40) | 40 (33) | 45 (37) | ||

| Female | 158 (65) | 1209 (60) | 81 (67) | 77 (63) | ||

| Enrollment season | .0001 | <.0001 | ||||

| 2004–2005 | 13 (5) | 247 (12) | 11 (9) | 2 (2) | ||

| 2005–2006 | 22 (9) | 99 (5) | 5 (4) | 17 (14) | ||

| 2006–2007 | 16 (7) | 144 (7) | 11 (9) | 5 (4) | ||

| 2007–2008 | 23 (9) | 162 (8) | 10 (8) | 13 (11) | ||

| 2008–2009 | 27 (11) | 132 (7) | 6 (5) | 21 (17) | ||

| 2009–2010 | 29 (12) | 217 (11) | 24 (20) | 5 (4) | ||

| 2010–2011 | 20 (8) | 134 (7) | 9 (7) | 11 (9) | ||

| 2011–2012 | 22 (9) | 104 (5) | 15 (12) | 7 (6) | ||

| 2012–2013 | 12 (5) | 190 (9) | 7 (6) | 5 (4) | ||

| 2013–2014 | 13 (5) | 136 (7) | 2 (2) | 11 (9) | ||

| 2014–2015 | 25 (10) | 252 (13) | 15 (12) | 10 (8) | ||

| 2015–2016 | 21 (9) | 197 (10) | 6 (5) | 15 (12) | ||

| Smoking statusa | <.0001 | .4 | ||||

| Current smoker | 10 (4) | 100 (5) | 3 (2) | 7 (6) | ||

| Current nonsmoker | 228 (94) | 1260 (63) | 115 (95) | 113 (93) | ||

| Unknown/missing | 5 (2) | 654 (32) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| High-risk comorbid conditions | ||||||

| COPD | 37 (15) | 444 (22) | .01 | 17 (14) | 20 (16) | .6 |

| CHF | 16 (7) | 211 (10) | .06 | 6 (5) | 10 (8) | .3 |

| Asthma | 33 (14) | 228 (11) | .3 | 15 (12) | 18 (15) | .6 |

| Immune-compromised | 15 (6) | 167 (8) | .3 | 5 (4) | 10 (8) | .2 |

| Diabetes | 51 (21) | 510 (25) | .1 | 20 (17) | 31 (25) | .09 |

| No. of ED visits in the prior 12 mo, median (min–max)b | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–15) | .5 | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–6) | .5 |

| No. of hospital admissions in the prior 12 mo, median (min–max)b | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–13) | .4 | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–6) | .003 |

| No. of outpatient visits w/ provider in the prior 12 mo, median (IQR)b | 8 (4–13) | 8 (4–15) | 1.0 | 8 (4–12) | 9 (5–15) | .04 |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

aSmoking status is missing for a larger proportion of non-RSV illnesses because these cases were not abstracted.

bWilcoxon test was used for differences in medians.

Common symptoms of RSV illness included sore throat, sputum production, cough, fever/feverishness, dyspnea, myalgia, and wheezing (Table 2). The most common diagnosis codes on the date of enrollment for RSV-positive patients were cough (45%), acute upper respiratory infection (21%), acute bronchitis (13%), acute sinusitis (12%), and bronchitis, unspecified (12%). Fifty-nine patients (24%) met the criteria for RSV-msLRTD during the enrollment encounter. The presence of RSV-msLRTD on enrollment was associated with a 3-fold higher risk of serious clinical outcome (relative risk, 2.99; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.83–4.88) (Table 3). RSV-positive participants with msLRTD during the enrollment encounter had a higher prevalence of COPD and congestive heart failure (CHF) and a greater number of medical encounters in the 28 days after enrollment (median, 1 vs 2; P = .05).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients With RT-PCR-Confirmed RSV Illness Stratified by Presence or Absence of RSV-msLRTD, Defined by at Least 3 of the Following Symptoms/Signs During the Initial Clinical Encounter: Cough, Wheezing (or Worsening in Baseline Wheezing), New Sputum Production (or Increase in Baseline Sputum), New (or Worsening) Shortness of Breath, and Observed Tachypnea (≥20 Breaths/Minute)

| Total RSV-Positive (n = 243), No. (%) | RSV-msLRTD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 184), No. (%) | Yes (n = 59), No. (%) | P d | ||

| Age group, y | .3 | |||

| 60–64 | 55 (23) | 38 (21) | 17 (29) | |

| 65–74 | 101 (42) | 78 (44) | 23 (35) | |

| 75+ | 87 (36) | 62 (35) | 25 (38) | |

| Gender | .009 | |||

| Male | 85 (35) | 56 (30) | 29 (49) | |

| Female | 158 (65) | 128 (70) | 30 (51) | |

| High-risk comorbid conditionsa | ||||

| COPD | 33 (14) | 18 (10) | 15 (25) | .002 |

| CHF | 22 (9) | 11 (6) | 11 (19) | .003 |

| Asthma | 48 (20) | 33 (18) | 15 (25) | .2 |

| Immune-compromised | 15 (6) | 7 (4) | 8 (14) | .01 |

| Diabetes | 51 (21) | 32 (17) | 19 (32) | .02 |

| Smoking status | .9 | |||

| Current smoker | 10 (4) | 7 (4) | 3 (5) | |

| Current nonsmoker | 228 (94) | 173 (94) | 55 (93) | |

| Unknown | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Enrollment visita | ||||

| Symptoms during enrollment visit | ||||

| Self-reported fever | 84 (35) | 53 (29) | 31 (53) | .0008 |

| Cough, productive | 117 (48) | 66 (36) | 51 (86) | |

| Cough, nonproductive | 109 (45) | 101 (55) | 8 (14) | |

| New/increased sputum | 120 (49) | 69 (38) | 51 (86) | |

| New/increased dyspnea (SOB) | 47 (19) | 6 (3) | 41 (69) | |

| Hemoptysis | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Chest pain | 18 (7) | 10 (5) | 8 (14) | .04 |

| Myalgia | 45 (19) | 32 (17) | 13 (22) | .4 |

| Wheezing | 39 (16) | 9 (5) | 30 (51) | <.0001 |

| Sore throat | 152 (63) | 113 (61) | 39 (66) | .5 |

| Exam during enrollment visit | ||||

| Fever ≥100°F | 20 (8) | 12 (7) | 8 (14) | .09 |

| Wheezing | 49 (20) | 15 (8) | 34 (58) | |

| Respiratory distress | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 5 (8) | .0006 |

| Tachypnea | 16 (7) | 1 (1) | 15 (25) | |

| Decreased breath sounds | 19 (8) | 6 (3) | 13 (22) | <.0001 |

| Crackles/rales | 23 (9) | 8 (4) | 15 (25) | <.0001 |

| Rhonchi | 31 (13) | 18 (10) | 13 (22) | .01 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Hospital admissionb | 29 (12) | 12 (7) | 17 (29) | <.0001 |

| ED visit | 13 (5) | 9 (5) | 4 (7) | .5 |

| X-ray-confirmed pneumonia | 23 (9) | 8 (4) | 15 (25) | <.0001 |

| No. of outpatient provider–attended medical encounters for acute illness within 28 d, median (IQR)c | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | .05 |

| Evaluations in the 28 d postenrollment | ||||

| Chest x-ray performed on date of enrollment visit | 94 (39) | 50 (27) | 44 (75) | <.0001 |

| Chest x-ray performed within 28 d | 118 (49) | 71 (39) | 47 (77) | <.0001 |

| O2 saturation measured within 28 d | 112 (46) | 69 (38) | 43 (73) | <.0001 |

| <90% O2 saturation | 11 (10) | 2 (3) | 9 (21) | .002 |

| Procalcitonin measured within 28 d | 7 (3) | 2 (1) | 5 (8) | .01 |

| Abnormal high | 3 (43) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | .4 |

| Hemoglobin measured within 28 d | 63 (26) | 34 (18) | 29 (49) | <.0001 |

| Abnormal low | 12 (19) | 6 (18) | 6 (21) | .8 |

| Abnormal high | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | .5 |

| Creatinine measured within 28 d | 76 (31) | 47 (26) | 29 (49) | .0007 |

| Abnormal high | 19 (25) | 13 (28) | 6 (21) | .5 |

| Leukocyte count measured within 28 d | 62 (26) | 33 (18) | 29 (49) | <.0001 |

| Leukopenia | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Leukocytosis | 7 (11) | 4 (12) | 3 (10) | .8 |

| Therapeutic interventions in the 28 d postenrollmenta | ||||

| Oxygen administered | 36 (15) | 17 (9) | 19 (32) | <.0001 |

| New bronchodilator/nebulizer treatment | 71 (29) | 37 (20) | 34 (58) | <.0001 |

| New/increased corticosteroid Rx | 44 (18) | 20 (11) | 24 (41) | <.0001 |

| New antibiotic prescription | 187 (77) | 135 (73) | 52 (88) | .02 |

| Antiviral prescription | 9 (4) | 8 (4) | 1 (2) | .7 |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; msLRTD, moderate to severe lower respiratory tract disease; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SOB, shortness of breath.

aHigh-risk comorbid conditions (except immune-compromised status, which was determined from electronic diagnosis codes), symptoms/exam findings from enrollment visit, and therapeutic interventions were obtained by medical record abstraction.

bThree additional hospital admissions occurred within 28 days for incarcerated hernia, small bowel obstruction, and acute gastrointestinal illness. These conditions were considered unrelated to the preceding RSV infection.

cWilcoxon test was used for differences in medians.

d P-values not shown for characteristics which contributed to the msLRTD case definition.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Patients With RT-PCR-Confirmed RSV Illness Stratified by Clinical Outcome Within 28 Days

| Mild RSV Outcome (n = 41), No. (%) |

Moderate RSV Outcome (n = 155), No. (%) |

Serious RSV Outcome (n = 47), No. (%) |

Relative Risk of Serious vs Nonserious Outcome (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | ||||

| 60–64 | 11 (27) | 40 (26) | 4 (9) | Ref |

| 65–74 | 15 (37) | 66 (43) | 20 (43) | 2.72 (0.98–7.57) |

| 75+ | 15 (37) | 49 (32) | 23 (49) | 3.64 (1.33–9.95) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 13 (32) | 54 (35) | 18 (38) | Ref |

| Female | 28 (68) | 101 (65) | 29 (62) | 0.87 (0.51–1.47) |

| High-risk comorbid conditionsa | ||||

| COPD | 1 (2) | 20 (13) | 12 (26) | 2.18 (1.27–3.76) |

| CHF | 2 (5) | 11 (7) | 9 (19) | 2.38 (1.33–4.25) |

| Asthma | 4 (10) | 32 (21) | 12 (26) | 1.39 (0.78–2.47) |

| Immune-compromised | 2 (5) | 8 (5) | 5 (11) | 1.81 (0.84–3.89) |

| Diabetes | 9 (22) | 29 (19) | 13 (28) | 1.44 (0.82–2.52) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker | 0 (0) | 9 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.51 (0.08–3.31) |

| Current nonsmoker | 41 (100) | 142 (92) | 45 (96) | Ref |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 1.01 (0.17–5.96) |

| Enrollment visita | ||||

| Symptoms during enrollment visit | ||||

| Self-reported fever | 9 (22) | 53 (34) | 22 (47) | 1.67 (1.00–2.77) |

| Cough, productive | 13 (32) | 74 (48) | 30 (64) | 1.90 (1.11–3.26) |

| Cough, nonproductive | 25 (61) | 70 (45) | 14 (30) | 0.52 (0.29–0.92) |

| New/increased sputum | 13 (32) | 75 (48) | 32 (68) | 2.19 (1.25–3.83) |

| New/increased dyspnea (SOB) | 1 (2) | 25 (16) | 21 (45) | 3.37 (2.09–5.44) |

| Hemoptysis | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | 3.56 (1.53–8.26) |

| Chest pain | 1 (2) | 10 (6) | 7 (15) | 2.19 (1.15–4.16) |

| Myalgia | 13 (32) | 19 (12) | 13 (28) | 1.68 (0.97–2.92) |

| Wheezing | 3 (7) | 30 (19) | 6 (13) | 0.77 (0.35–1.68) |

| Sore throat | 27 (66) | 99 (64) | 26 (55) | 0.74 (0.44–1.24) |

| Exam during enrollment visit | ||||

| Fever ≥100°F | 1 (2) | 10 (6) | 9 (19) | 2.64 (1.50–4.64) |

| Wheezing | 3 (7) | 25 (16) | 21 (45) | 3.20 (1.98–5.18) |

| Respiratory distress | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 5 (11) | 4.70 (3.00–7.38) |

| Tachypnea | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 12 (26) | 4.86 (3.21–7.37) |

| Decreased breath sounds | 1 (2) | 12 (8) | 6 (13) | 1.73 (0.84–3.54) |

| Crackles/rales | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 16 (34) | 4.94 (3.23–7.54) |

| Rhonchi | 3 (7) | 19 (12) | 9 (19) | 1.62 (0.87–3.01) |

| RSV-msLRTD at enrollment | 3 (7) | 33 (21) | 23 (49) | 2.99 (1.83–4.88) |

Serious outcomes included hospital admission, ED visit, and pneumonia. Moderate outcomes included new antibiotic or antiviral therapy, new/increased bronchodilator therapy, and new/increased systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; msLRTD, moderate to severe lower respiratory tract disease; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SOB, shortness of breath.

aHigh-risk comorbid conditions (except immune-compromised status, which was determined from electronic diagnosis codes) and symptoms/exam findings from enrollment visit were obtained by medical record abstraction.

The clinical outcome for RSV illness was serious in 47 (19%), moderate in 155 (64%), and mild in 41 (17%). Nearly half of serious outcomes occurred in patients ≥75 years of age with RSV infection (Table 3). Serious outcomes were not mutually exclusive and included hospital admission (n = 29), ED visit (n = 13), and pneumonia (n = 23). The 13 ED visits included 5 patients who were admitted and 8 who were discharged. Among 155 patients with a moderate outcome, 144 (93%) received a new antibiotic prescription, 45 (29%) received bronchodilator or nebulizer treatment, and 28 (18%) received new systemic corticosteroid therapy; 5 (3%) were treated with an antiviral drug. The risk of a serious outcome was approximately double for patients with COPD or CHF compared with patients without these conditions (Table 3).

Thirty-two participants with RSV infection were admitted to a hospital within 28 days. Three of these hospitalizations were for noncardiopulmonary conditions that were unlikely to be related to RSV infection, including incarcerated hernia, small bowel obstruction, and acute gastrointestinal illness. These 3 hospital admissions were excluded from the serious outcome group. Fifteen of the remaining 29 hospitalized patients were enrolled in the inpatient setting. Four of those were directly admitted from an outpatient clinic, whereas the remaining 11 were admitted from the emergency department. Seven patients were enrolled during an outpatient encounter on the same day as their hospital admission, leaving 7 with hospital admissions 1 or more days after enrollment. The median interval from symptom onset to admission for RSV-positive hospitalized individuals was 4 days.

Preexisting chronic diseases were common among hospitalized patients with RSV, including COPD (n = 9; 31%), CHF (n = 8; 28%), asthma (n = 8; 28%), and diabetes (n = 9; 31%) (Table 4). Twenty-one (72%) received a discharge diagnosis of respiratory tract infection (eg, pneumonia, bronchitis, exacerbation of COPD). Only 1 patient was recognized to have RSV at the time of hospital discharge. The mean (SD) duration of hospital admission was 3.5 (2.5) days. Twenty-seven (93%) were discharged to home, and 2 (7%) were transferred to a rehabilitation or long-term care facility; there were no deaths within 28 days. The hospital course was uncomplicated for most patients. None required mechanical ventilation or ICU admission. Twenty-five (86%) received antimicrobials; 4 (16%) were treated with antiviral drugs.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Patients With RT-PCR-Confirmed RSV Illness and Hospitalization on or Within 28 Days of Enrollment

| Hospitalized RSV-Positive (n = 29), No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age group, y | |

| 60–64 | 2 (7) |

| 65–74 | 11 (38) |

| 75+ | 16 (55) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (31) |

| Female | 20 (69) |

| High-risk comorbid conditions | |

| COPD | 9 (31) |

| CHF | 8 (28) |

| Asthma | 8 (28) |

| Immune-compromised | 5 (17) |

| Diabetes | 9 (31) |

| RSV-msLRTD symptoms at enrollment | 17 (59) |

| Cardiopulmonary-related admission diagnosisa | 27 (93) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current smoker | 1 (3) |

| Current nonsmoker | 27 (93) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) |

| Median interval from symptom onset to hospital admission (range), d | 4.0 (1–15) |

| Median number of days in the hospital (range) | 3.0 (1–12) |

| Outcome | |

| Discharged home | 27 (93) |

| Transferred to rehabilitation/nursing | 2 (7) |

| Interventions received during hospital stay | |

| CPAP or BiPAP | 3 (10) |

| New/supplemental O2 | 18 (62) |

| ICU admission | 0 (0) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 (0) |

| Antimicrobials administered | 25 (86) |

| Antivirals administered | 4 (14) |

Abbreviations: BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; msLRTD, moderate to severe lower respiratory tract disease; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

To estimate the number of hospitalized RSV cases that were not included in this analysis, we extracted hospital diagnosis codes for community cohort members during periods of study enrollment. We identified an additional 20 individuals ≥60 years of age who were hospitalized during study enrollment periods with a diagnosis code for RSV but were not enrolled in the influenza vaccine effectiveness study.

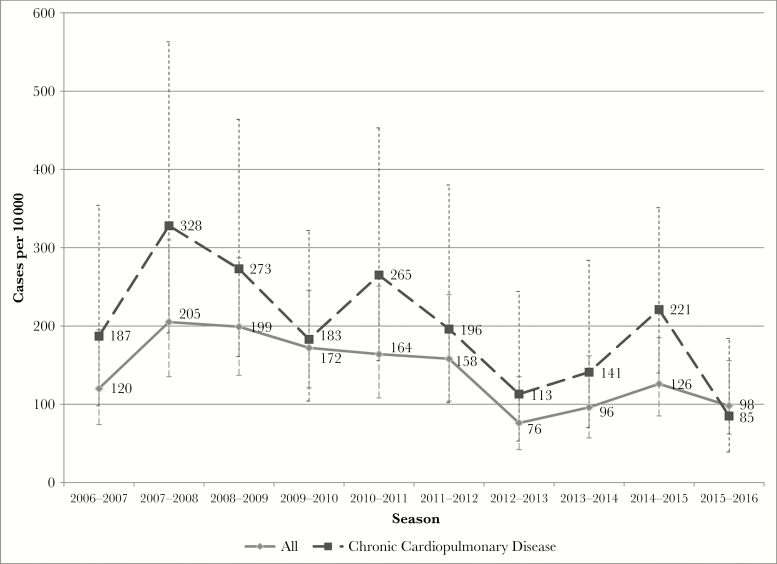

The median community cohort size for adults aged ≥60 years was 13 807 (range, 12 142–13 807) for the seasons from 2006–2007 through 2015–2016. The overall seasonal incidence of medically attended RSV illness was 139 cases per 10 000 (95% CI, 122–160). The RSV incidence was 196 cases per 10 000 (95% CI, 162–236) among persons with chronic cardiopulmonary disease and 103 (95% CI, 85–125) among those without cardiopulmonary disease (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.89; 95% CI, 1.44–2.48). There was a significant decline in the incidence of medically attended RSV from 2006–2007 through 2015–2016 for the entire cohort (P = .003, chi-square test for trend) and for those with cardiopulmonary disease (P = .014, chi-square test for trend). The incidence of medically attended RSV was also higher in women compared with men (IRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.09–1.95). The overall incidence rates of medically attended illness caused by RSV A and RSV B were nearly identical (IRR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.75–1.35), although 1 or the other subtype was often dominant during a single season. The temporal trend in RSV incidence suggests an overall reduction among adults ≥60 years of age after the 2011–2012 season (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus by season in a community cohort of individuals ≥60 years of age (gray solid line) and among the subset of individuals with chronic cardiopulmonary disease (dashed black line).

We compared the peak month for RSV and influenza positives during each season among study participants ≥60 years old. In 7 seasons, the RSV peak and the influenza peak occurred in the same calendar month. In 2 seasons, the RSV peak occurred before the influenza peak, and in 3 seasons, the RSV peak occurred after the influenza peak. We also compared the peak month for RSV detection among study participants with the peak month based on local clinical testing of children <24 months. In 5 seasons, the peak calendar month was the same for enrolled adults ≥60 years old and children; the pediatric peak occurred 1–2 months earlier in 5 seasons and 1 month later in 2 seasons.

DISCUSSION

In a longitudinal assessment over 12 seasons in a single community, we found that RSV was a common cause of outpatient respiratory illness in adults ≥60 years of age. RSV was detected in 11% of those with medically attended acute respiratory illness, and it was the second most common viral pathogen in this age group. The number of RSV A and RSV B cases was similar overall, but 1 subtype was usually dominant during any given season. The seasonal incidence of medically attended RSV was variable but was consistently higher in persons with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease.

Moderate or serious outcomes, including change in therapy, hospital admission, and pneumonia, occurred in >80% of patients with laboratory-confirmed RSV infection. Serious outcomes (hospital admission, ED visit, or pneumonia) occurred in nearly 1 of every 5 patients with RSV infection. Patients with serious outcomes were significantly more likely to present with dyspnea and objective signs of lower respiratory tract involvement, including wheeze, rales, and rhonchi. Hospital admission was the most common serious outcome, and the risk of a serious outcome increased with age. Serious RSV illness was significantly associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure.

The majority of outpatient RSV cases (64%) resulted in a moderate outcome, including a new prescription for antibiotics, antivirals, bronchodilators, or systemic corticosteroids. Nearly half of individuals with RSV required a chest x-ray and measurement of oxygen saturation during the enrollment visit or follow-up period. Overall, the most common therapeutic interventions included new antibiotic prescription and bronchodilator/nebulizer treatment. More than three-quarters of patients with RSV were treated with antibiotics. Although this study did not evaluate bacterial coinfections, it is possible that many of these antibiotic courses were unnecessary.

Few studies have assessed the occurrence, clinical spectrum, and outcomes for RSV illness among older adults in the outpatient setting. A sentinel system in the United Kingdom identified RSV in 15% of adults ≥65 years old with medically attended acute respiratory illness [28]. This is similar to the percent positive (11%) that we observed over 12 seasons in adults ≥60 years old. In a previous study over a shorter time period, we found that cough, nasal congestion, and wheezing were more common in adults ≥50 years old with RSV compared with those with other causes of acute respiratory illness [29]. Prospective RSV illness surveillance in nearly 3000 healthy, working-age adults from 1975 to 1995 demonstrated that 84% of RSV infections were symptomatic [30]. Of the latter, 22% involved the lower respiratory tract (tracheobronchitis or wheezing). Additional studies are needed in diverse populations to estimate the burden of adult RSV illness and the potential impact of future licensed vaccines.

RSV-associated moderate to severe lower respiratory tract illness is a composite measure of lower respiratory tract illness that has been used as a proxy for serious respiratory disease outcomes in RSV vaccine clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02608502 and NCT02266628). In this study, we found that RSV-msLRTD at the time of enrollment was significantly associated with a serious clinical outcome. In particular, patients with RSV-msLRTD at enrollment were significantly more likely to require hospital admission and were also more likely to develop pneumonia during the follow-up period. The incremental risk (absolute risk difference) for each of these outcomes exceeded 20% when RSV-msLRTD was present at enrollment. These findings suggest that RSV-msLRTD may be a useful surrogate measure to identify individuals at risk for more serious clinical end points in trials of vaccines and antivirals.

The strengths of this study include consistent prospective recruitment of patients with acute respiratory illness from a defined community cohort, inclusion of 12 consecutive winter seasons, collection of standardized clinical data during the enrollment encounter, and detailed abstraction of outpatient and inpatient medical records for the 28-day follow-up period.

This observational study also has several limitations. Recruitment was restricted to individuals who sought medical care for respiratory illness during periods of influenza transmission, and cough was required for enrollment during seasons after the 2009 pandemic. This study underestimated the occurrence of RSV hospital admissions as enrollment was restricted to primary care and urgent care outpatient clinics after 2010. Based on diagnosis codes, we identified an additional 20 individuals ≥60 years old in our community cohort who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of RSV but not enrolled in the vaccine effectiveness study. These patients were most likely admitted through the emergency department or subspecialty clinics where study recruitment did not occur. In addition, some RSV cases may have been missed by RT-PCR testing, as serology has been shown to improve the detection of RSV infection in adults with community-acquired pneumonia [31]. Finally, this study was conducted in a largely rural and racially homogenous population, and results may not reflect outpatient RSV occurrence and outcomes in urban and racially diverse settings.

As new vaccines and antivirals are licensed for RSV prevention and treatment in adults, there will be a great need for data to estimate the population burden and the potential reduction in cases and serious outcomes. The potential impact on reducing antimicrobial use is another potential benefit that requires further evaluation. These data will be needed to increase awareness of RSV among adult health care providers and to inform cost-effectiveness analyses for public health planning and policy deliberations. In preparation for these decisions, additional research is urgently needed to estimate disease burden and outcomes in larger and more diverse populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of the following individuals: Elizabeth Armagost, Deanna Cole, Katherine Graebel-Khandakani, Sherri Guzinski, Linda Heeren, Lynn Ivacic, Nicole Kaiser, Diane Kohnhorst, Sarah Kopitzke, Tamara Kronenwetter Koepel, Ariel Marcoe, Vicki Moon, Suellyn Murray, Madalyn Palmquist, Rebecca Pilsner, DeeAnn Polacek, Emily Redmond, Maria Rotar, Carla Rottscheit, Elisha Stefanski, Sandy Strey, and Abby Winkler.

Financial support. This research was supported by Novavax, Inc.

Potential conflicts of interest. E.A.B., J.P.K., J.K.M., and B.A.K. have received research support from Novavax, Inc. V.S. is employed by Novavax, Inc. The other authors declare no conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Matias G, Taylor R, Haguinet F, et al. . Estimates of mortality attributable to influenza and RSV in the United States during 1997-2009 by influenza type or subtype, age, cause of death, and risk status. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2014; 8:507–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dia N, Richard V, Kiori D, et al. . Respiratory viruses associated with patients older than 50 years presenting with ILI in Senegal, 2009 to 2011. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ju X, Fang Q, Zhang J, et al. . Viral etiology of influenza-like illnesses in Huizhou, China, from 2011 to 2013. Arch Virol 2014; 159:2003–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCracken JP, Prill MM, Arvelo W, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus infection in Guatemala, 2007–2012. J Infect Dis 2013; 208(Suppl 3):S197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morales F, Calder MA, Inglis JM, et al. . A study of respiratory infections in the elderly to assess the role of respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect 1983; 7:236–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kimball AM, Foy HM, Cooney MK, et al. . Isolation of respiratory syncytial and influenza viruses from the sputum of patients hospitalized with pneumonia. J Infect Dis 1983; 147:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agius G, Dindinaud G, Biggar RJ, et al. . An epidemic of respiratory syncytial virus in elderly people: clinical and serological findings. J Med Virol 1990; 30:117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Falsey AR. Noninfluenza respiratory virus infection in long-term care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1991; 12:602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takimoto CH, Cram DL, Root RK. Respiratory syncytial virus infections on an adult medical ward. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:706–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Englund JA, Anderson LJ, Rhame FS. Nosocomial transmission of respiratory syncytial virus in immunocompromised adults. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29:115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harrington RD, Hooton TM, Hackman RC, et al. . An outbreak of respiratory syncytial virus in a bone marrow transplant center. J Infect Dis 1992; 165:987–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anaissie EJ, Mahfouz TH, Aslan T, et al. . The natural history of respiratory syncytial virus infection in cancer and transplant patients: implications for management. Blood 2004; 103:1611–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mishra B, Malhotra P, Mandall J, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus is not an important community acquired pathogen in adult hematological malignancy patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2006; 37:1132–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1749–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dowell SF, Anderson LJ, Gary HE Jr, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus is an important cause of community-acquired lower respiratory infection among hospitalized adults. J Infect Dis 1996; 174:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Falsey AR, McElhaney JE, Beran J, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viral infections in older adults with moderate to severe influenza-like illness. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:1873–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Widmer K, Zhu Y, Williams JV, et al. . Rates of hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and influenza virus in older adults. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee N, Lui GC, Wong KT, et al. . High morbidity and mortality in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1069–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sundaram ME, Meece JK, Sifakis F, et al. . Medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infections in adults aged ≥50 years: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:342–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McClure DL, Kieke BA, Sundaram ME, et al. . Seasonal incidence of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infection in a community cohort of adults ≥50 years old. PLoS One 2014; 9:e102586–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fries L, Shinde V, Stoddard JJ, et al. . Immunogenicity and safety of a respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein (RSV F) nanoparticle vaccine in older adults. Immun Ageing 2017; 14:8–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Belongia EA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, et al. ; Marshfield Influenza Study Group Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccines varied substantially with antigenic match from the 2004-2005 season to the 2006-2007 season. J Infect Dis 2009; 199:159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belongia EA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, et al. . Influenza vaccine effectiveness in Wisconsin during the 2007-08 season: comparison of interim and final results. Vaccine 2011; 29:6558–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME, et al. . Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012-2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Chung J, et al. ; US Flu VE Investigators; US Flu VE Investigators 2014-2015 influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States by vaccine type. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:1564–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Popowitch EB, O’Neill SS, Miller MB. Comparison of the Biofire FilmArray RP, Genmark eSensor RVP, Luminex xTAG RVPv1, and Luminex xTAG RVP fast multiplex assays for detection of respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:1528–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Simpson MD, Kieke BA Jr, Sundaram ME, et al. . Incidence of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus and influenza illnesses in children 6-59 months old during four seasons. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3(X):XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zambon MC, Stockton JD, Clewley JP, Fleming DM. Contribution of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus to community cases of influenza-like illness: an observational study. Lancet 2001; 358:1410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sundaram ME, Meece JK, Sifakis F, et al. . Medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infections in adults aged ≥50 years: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:342–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in previously healthy working adults. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:792–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y, Sakthivel SK, Bramley A, et al. . Serology enhances molecular diagnosis of respiratory virus infections other than influenza in children and adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55:79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]