Abstract

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic, progressive, debilitating, scarring and crippling disorder of the oral cavity. It is a potentially malignant oral disease which predominantly affects people of South and Southeast Asia, especially Indian subcontinent, where chewing of areca nut and its commercial preparation is rampant. However, due to increase in immigration of people from the Indian subcontinent, the health professionals in many developed countries do come across this disease very often. Since decades, many treatment modalities are suggested and studied using medicines, surgery and physiotherapy, with varying degrees of benefit, but none have been able to cure this disease completely, and hence, it has become a challenging condition. The present article emphasizes on various therapeutic interventions used till date to curb the menace of this disease and the principal author with his vast academic research and clinical experience in treating this disease has proposed the stage-wise treatment regimen for OSMF. The current article is an attempt to compile the available treatment, its current status and future perspectives, so as to assist early intervention of the disease with evidence-based approach. This article will ignite the research minds of dental clinician, oral medicine specialist, otolaryngologist and general physician in treating OSMF.

Keywords: Areca nut, evidence-based treatment, oral submucous fibrosis, protocol, therapeutic interventions, tobacco

INTRODUCTION

Oral cavity is rightly described as mirror of the body as it reflects the health of the individual. Oral mucosa is a unique tissue, lined by keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium and underlying connective tissue (lamina propria). The oral mucosa is continuously exposed to chemicals, microorganisms, thermal changes and mechanical irritants (tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, etc). The epithelial and connective tissue components of the oral mucosa demonstrate acute and chronic reactive changes in response to the above stressors.[1,2] The keratinized epithelium which is present on the dorsum of the tongue, such as hard palate and attached gingiva, shows less reactive changes to the stressors as compared to the nonkeratinized epithelium, which is seen everywhere in the oral cavity including the buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, alveolar mucosa and specialized mucosa. Changes indicative of disease are seen as alterations in the oral mucosal lining.[2,3,4,5,6]

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic, insidious, progressive, debilitating, scarring, irreversible, complex and crippling disorder of the oral cavity.[4,5,6,7,8] This oral potentially malignant disorder (OPMD) a collagen disorder was first described as early as 600 BC by Sushruta, the renowned Indian physician, as Vidari. Schwartz in 1952 after observing similar features in five Indian women of Kenya described this condition as progressive inability to open the mouth due to loss of elasticity and development of vertical fibrous bands in the labial and buccal tissues. He termed it as atrophia idiopathica mucosae oris. In 1953, Dr. S.G. Joshi coined the term OSMF for the disease.[5,6,7,8] Subsequently, various researchers classified OSMF both, clinically and histologically – Desa (1957), Pindborg and Sirsat (1966), Agarwal et al. (1971), Pindborg (1989), Katharia et al. (1992), Nagesh and Bailor (1993), Maher et al. (1996), Ranganathan et al. (2001), Rajendran (2003), Kiran Kumar et al. (2007), Tinky Bose and Anita Balan (2007) and Chandramani More (2012).[5,8]

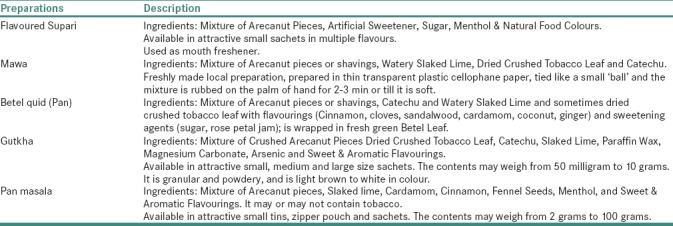

OSMF is predominantly seen in people of South and Southeast Asia – India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Taiwan, Southern China, etc., where chewing of betel quid, areca nut or its flavored formulations is frequently practiced. The rapid increase in the prevalence of this disease is due to an upsurge in the popularity of commercially available areca nut and tobacco preparations – gutkha, pan masala, flavored areca nut, mawa, etc., in Asian countries [Table 1]. It causes significant morbidity, in terms of loss of mouth function as tissues become rigid and mouth opening becomes difficult, and mortality because of transformation into squamous cell carcinoma.[4,5,6,8,9,10,11,12]

Table 1.

Commercially available arecanut preparations

The prevalence rate of OSMF in Indian population differs geographically. The male-to-female ratio of OSF was 4.9:1.[8,10,11] A considerable difference in the prevalence of OSMF in Europe, UK, USA and Middle East countries has been reported on Asian migrants. Sporadic cases among the non-Asians have also been reported in the literature.[8,12,13,14]

OSMF affects the upper digestive tract – oral cavity, oropharynx and upper third of esophagus and is characterized by Juxta – epithelial inflammatory reaction, followed by fibroelastic changes due to progressive fibrosis of the submucosal tissues (lamina propria and deeper connective tissues) with epithelial atrophy leading to stiffness and rigidity of the oral mucosa and eventual inability to open the mouth.[4,8,10,11,13,14]

The etiology of OSMF is obscure, although various hypotheses are proposed, suggesting multifactorial origins, such as chewing of areca nut and its flavored formulations (most common), chronic nutritional deficiencies (especially iron, Vitamin B complex and protein) and genetic predisposition, autoimmunity Excessive use of areca nut and its flavored formulations disrupts the hemostatic equilibrium between synthesis and degeneration.[4,7,8,9,11,15,16] The copper ion in areca nut increases the activity of lysyl oxidase leading to unregulated collagen production, thereby causing oral fibrosis. This leads to the production of free radicals and reactive oxygen species, which are responsible for high rate of oxidation–peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids.[2,4,8,17,18,19]

OSMF is a disease of middle age group with peak incidence observed in the second to fourth decade of life. The sex distribution of OSMF varies geographically. The most common oral site for OSMF is buccal mucosa and retromolar region, followed by soft palate, faucial pillars, floor of mouth, tongue, labial mucosa and gingiva[2,4,6,8,11,12] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Oral submucous fibrosis involving various areas of the oral cavity. (a and b) Significant blanching and presence of palpable, thick fibrous bands on the left and right buccal mucosa. Note the brownish-black pigmentation in the posterior vestibular region in b. (c and d) Blanching of the soft palate and faucial pillars. Note the shrunken uvula and its altered shape. (e) Blanching of the floor of mouth and loss of surface texture. (f-i) Blanching and palpable fibrous bands of the upper and lower labial mucosa. Note the stiff labial mucosa and presence of blanching of attached gingiva in f and g

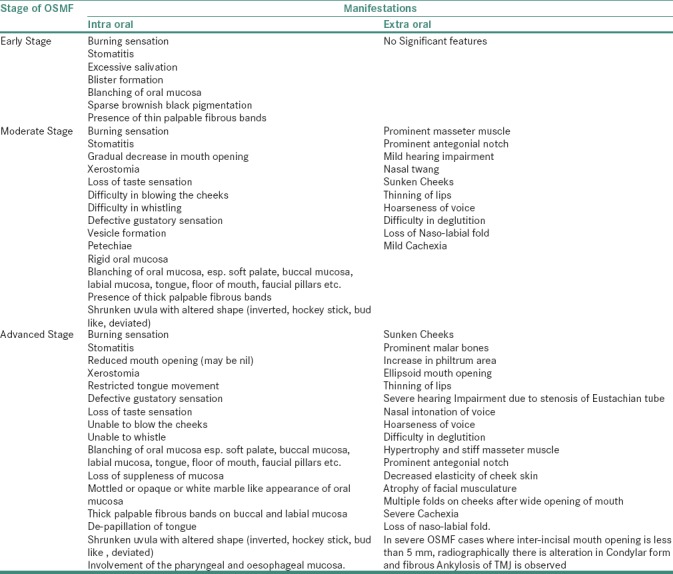

The clinical presentation will vary according to the stage of the disease, as mentioned in Table 2.[2,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,18,20] In contrast to other OPMD's, OSMF is insidious in origin and does not regress, either spontaneously or with cessation of habit. The disease remains either stationary or becomes severe, leaving an individual handicapped, both physically and psychologically.[2,8,11] Usually, the OSMF lesion shall be biopsied, especially if there are ulcerative, nodular, erythematous and suspicious areas. The histologically proven severe or moderate epithelial dysplasia shall be treated in the lines of management of carcinoma. Nondysplastic or mildly dysplastic cases must be kept under long-term observation and shall be advised antioxidant therapy after discontinuation of habit.[8,10,18,21,22]

Table 2.

Clinical Oro- facial manifestations

Early diagnosis of OSMF is important in both prevention and therapeutic procedures of oral cancers.[6,8,10,11] The treatment of OSMF in the last few decades is varied and ineffective, but till date, there is no consensus on the most appropriate management of OSMF. Many treatment protocols for OSMF have been proposed by various researchers since its first diagnosis, so as to alleviate the signs and symptoms of the disease and also to stop the disease progression and malignant transformation. In spite of numerous drugs or interventions in practice, the complete remission of OSMF is not achieved and is unsatisfactory. Hence, an attempt of finding a permanent cure is still in progress.

TREATMENTS IN PRACTICE

In recent times, several medicinal (allopathic, homeopathic and Ayurvedic), surgical, physiotherapeutic, etc., have been tried, either alone or in combination, in the treatment of OSMF. In advance cases, surgical intervention is the only treatment modality, but relapse is a major problem. Discontinuation of harmful substance such as areca nut, tobacco and alcohol; increased intake of fresh red fruits and green leafy vegetables [Figure 2] and mineral-rich diet has also been advised.[8] The authors have also made an attempt to compile the present treatment which is in practice, and several following studies conducted in different parts of the world.

Figure 2.

Various fruits and vegetables having antioxidant properties

The studies of Borle and Borle,[13] Khanna and Andrade et al.,[14] Maher et al.[15] and Thakur et al.[16] on multivitamins; Borle and Borle[13] and Nallapu et al.[17] on Vitamin A; Kumar et al.,[18] Karemore and Motwani,[19] Selvam and Dayanand,[23] Patil et al.[21] and Samuel and Renukananda[22] on lycopene; Hastak et al.,[20] Das et al.,[24] Agrawal et al.[25] and Yadav et al.[26] on curcumin; Rajendran et al.[27] and Mehrotra et al.[28] on pentoxifylline; Bhadage et al.[29] on isoxsuprine; Gupta and Sharma[30] on chymotrypsin; Borle and Borle,[13] Krishnamoorthy and Khan,[31] James et al.[32] and Shah et al.[33] on hyaluronidase; James et al.[32] on dexamethasone; Katharia et al.[34] and Ali et al.[35] on placental extract; Jirge et al.[36] on levamisole; Haque et al.[37] on interferon gamma; Goel and Ahmed[38] and Gupta et al.[39] on steroids; Khanna and Andrade et al.[14] Shetty et al.[40] and Mulk et al.[41] on spirulina; Alam et al.[42] and Sudarshan et al.[43] on Aloe vera; Cox and Zoellner et al.[44] on physiotherapy exercises; have put forward positive and negative observations in the treatment of OSMF.

PROPOSED TREATMENT

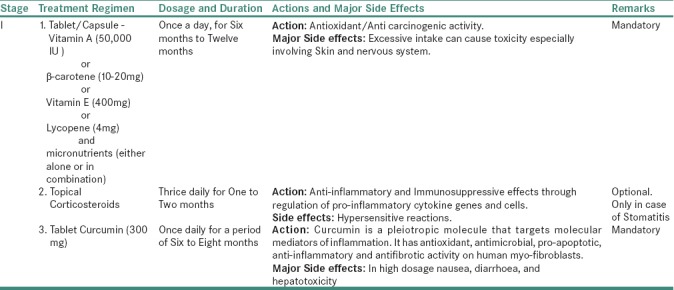

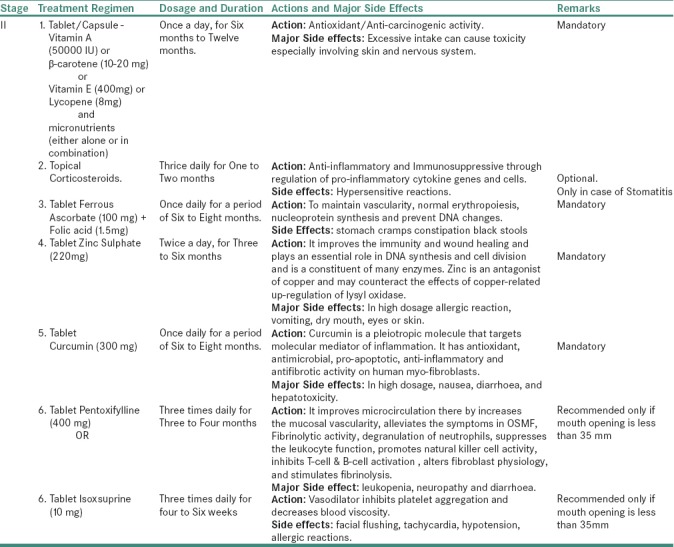

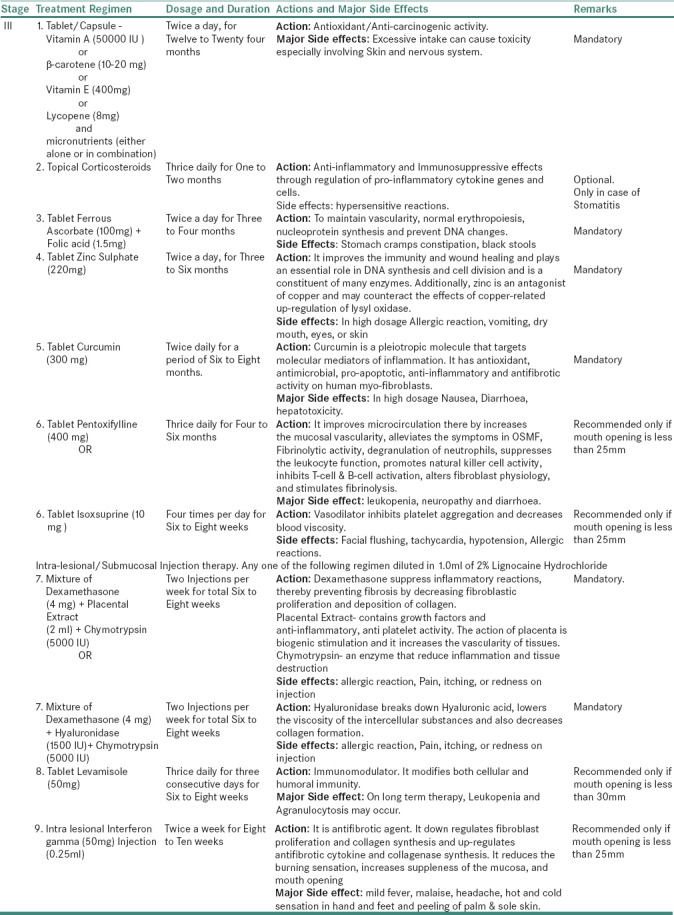

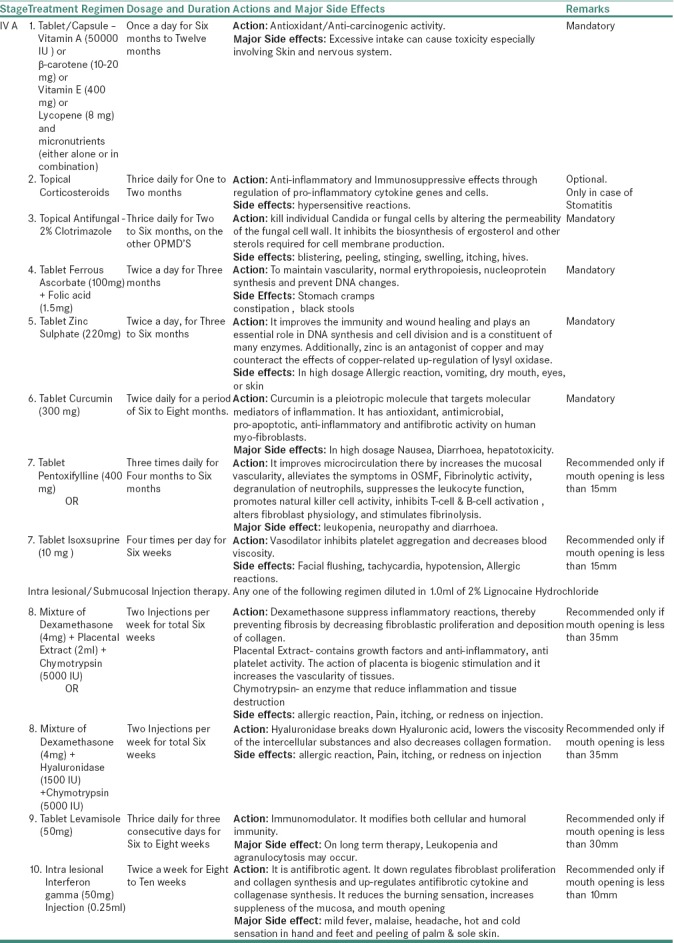

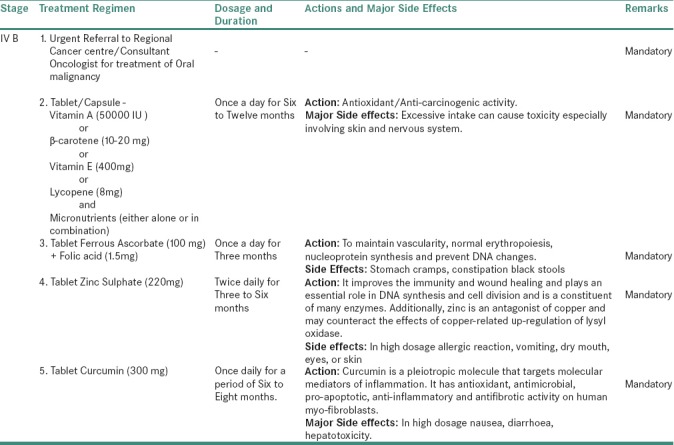

Various treatment regimens for OSMF are proposed to alleviate the signs and symptoms of the disease. Even after seven decades of its description as a precancerous condition, no substantial treatment is available because of its multimodal pathogenesis.[12] The principal author with his vast academic and clinical experience in treating various oral lesions, especially OPMD's, has proposed stage-wise treatment protocol or regimen for OSMF so as to assist early intervention of the disease [Tables 3a–e].

Table 3a.

For Stage I OSMF

Table 3b.

For Stage II OSMF

Table 3c.

For Stage III OSMF

Table 3d.

For stage IVA OSMF

Table 3e.

For stage IVB OSMF

In addition to the above-proposed treatment protocol, each patient of OSMF shall be counseled for discontinuation of habit and must be advised with increase intake of fresh red fruits and green leafy vegetables along with physiotherapy exercises, especially ballooning, blowing of mouth, opening and closing of the mouth, hot water gargling, etc. The frequency of exercise will depend on the severity of the disease.[8,11,18,23]

DISCUSSION

From the last two decades, use of clinical protocol or guidelines have increased and has become a part of routine practice worldwide. The clinical guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. Most of the hospitals have formulated their own standard operating procedures, which may offer concise instructions on diagnostic or screening test, medical or surgical services, etc. These guidelines act as a tool for making care more consistent and efficient and help in reducing the gap between the clinician's knowledge and the available scientific evidence. Various health specialties and companies are involved in conflict to gain rights over specific procedures or treatments as guidelines or protocols.[45,46]

The clinical protocol helps in providing quality of care to the patients, but its outcome is not clear; maybe because of difference in understanding, the extent of quality by the stakeholders and hence, the effectiveness of protocol remains incomplete. Protocols have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality and improve quality of life, at least for some conditions, especially when they promote interventions of proved benefit.[47]

Such protocols empower patients to make choices, their personal needs and preferences in selecting the best option. Certainly, sometimes clinicians may first learn about new protocols from patients. The treatment protocols based on a critical appraisal of scientific evidence explain which interventions are of proved benefit. Sometimes, the most important limitation of the protocols is that the recommendations maybe wrong for individual patients.[45,46,47,48]

There is lack of consistent evidence for the effectiveness of any specific interventions for the management of OSMF, and it is difficult to correlate or even combine their outcomes in a scientifically meaningful manner. The literature remains confused because of lack of clarity in scoring system and agreeable treatment outcome measures. Numerous treatments are tried for OSMF, but only few clinical trials are undertaken. Literature has reported variety of clinical outcomes because of failure to standardize the clinical severity scores for OSMF and clarity in distinguishing treatment designs.

Till date, not a single treatment modality has provided a complete relief for this condition, which has high malignant potential. It is difficult to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of each treatment, especially in combined treatment protocols, because of the empirical nature of each approach. The proposed evidence-based novel clinical protocol for therapeutic intervention is to improve the quality of life in patients suffering from the debilitating condition, OSMF. The present protocol aims to provide the best possible treatment regimen based on sound evidence. The principal author with his vast academic and clinical experience in treating this disease has proposed the stage-wise treatment regimen for OSMF. An attempt is made to compile the available treatment, its current status and future perspectives, so as to assist early intervention of the disease with evidence-based approach.

CONCLUSION

The evidence for the prevention of any oral disease starts with an understanding of its burden at different stages of life. The time-tested health policies and priority settings direct to have preventive interventions. A variety of treatments are rendered for OSMF till date. The present article has explored all the treatment options available in the existing literature and has suggested the evidence-based treatment protocols for the intervention of OSMF. There is always a scope for further research in the suggested treatment protocol.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatnagar P, Rai S, Bhatnagar G, Kaur M, Goel S, Prabhat M, et al. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions, mucosal variants, and treatment required for patients reporting to a dental school in North India: In accordance with WHO guidelines. J Family Community Med. 2013;20:41–8. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.108183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.More C, Shah P, Rao N, Pawar R. Oral submucous fibrosis: An overview with evidence based management. Int J Oral Health Sci Adv. 2015;3:40–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markiewicz M, Margarone J, Barbagli G, Scannapieco F. Oral mucosa harvest: An overview of anatomic and biologic considerations. Eur Assoc Urol. 2007;5:179–87. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; terminology, classification and present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.More C, Gupta S, Joshi J, Varma S. Classification system of oral submucous fibrosis. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2012;24:24–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher R, Sankaranarayanan R, Johnson NW, Warnakulasuriya KA. Evaluation of inter-incisor distance as an objective criterion of the severity of oral submucous fibrosis in karachi, pakistan. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B:362–4. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(96)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jontell M, Holmstrup H. Red and white lesions of the oral mucosa. In: Greenberg M, Glick M, Ship J, editors. Burket's Oral Medicine. 11th ed. Jericho, England: Hamilton; 2008. pp. 88–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.More C, Das S, Patel H, Adalja C, Kamatchi V, Venkatesh R. Proposed clinical classification for oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:200–2. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daftary D, Murti P, Bhonsle R, Gupta P, Mehta F, Pindborg J. Oral precancerous lesions and conditions of tropical interest. In: Prabhu S, Wilson D, Daftary D, Johnson N, editors. Oral Diseases in the Tropics. Jericho, England: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 417–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.More C, Mukesh A, Hetal P, Chhaya A. Oral submucous fibrosis – A hospital based retrospective study. J Pearl Dent. 2010;1:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazarey V, Erlewad D, Mundhe K, Ughade S. Oral submucous fibrosis: Study of 1000 cases from central India. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:12–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fry R, Goyal S, Pandher P, Chawla J. An approach to management of oral submucous fibrosis: Current status and review of literature. Int J Curr Res. 2014;6:10598–604. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borle R, Borle S. Management of oral submucous fibrosis: A conservative approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:788–91. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanna JN, Andrade NN. Oral submucous fibrosis: A new concept in surgical management. Report of 100 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24:433–9. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maher R, Aga P, Johnson NW, Sankaranarayanan R, Warnakulasuriya S. Evaluation of multiple micronutrient supplementation in the management of oral submucous fibrosis in Karachi, Pakistan. Nutr Cancer. 1997;27:41–7. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur N. Effectiveness of micronutrients and physiotherapy in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Contempt Dent. 2011;2:101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nallapu V, Balasankuli B, Vuppalapati H, Sambhana S, Dayanandam M, Koppula S. Efficacy of Vitamin E in oral submucous fibrosis: A clinical and histopathologic study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2015;27:387–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V, Singh M. Efficacy of lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karemore TV, Motwani M. Evaluation of the effect of newer antioxidant lycopene in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23:524–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.104964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hastak K, Lubri N, Jakhi SD, More C, John A, Ghaisas SD, et al. Effect of turmeric oil and turmeric oleoresin on cytogenetic damage in patients suffering from oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Lett. 1997;116:265–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil S, Sghaireen M, Maheshwari S, Kunsi S, Sahu R. Comparative study of the efficacy of lycopene and aloe vera in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Health Al Sci. 2015;4:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuel H, Renukananda G. Comparative study between intralesional steroid injection and oral lycopene in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Sci Study. 2015;2:20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvam N, Dayanand A. Lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Asian J Pham Clin Res. 2013;6:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das D, Balan A, Balan A, Sreelatha K. Comparative study of the efficacy of curcumin and turmeric oil as chemopreventive agents in oral submucous fibrosis: A clinical and histolpathological evaluation. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2010;22:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal N, Singh D, Sinha A, Srivastava S, Prasad R, Singh G. Evaluation of efficacy of turmeric in management of oral submucous fibrosis. J Indain Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2014;26:260–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yadav M, Aravinda K, Saxena VS, Srinivas K, Ratnakar P, Gupta J, et al. Comparison of curcumin with intralesional steroid injections in oral submucous fibrosis – A randomized, open-label interventional study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2014;4:169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajendran R, Rani V, Shaikh S. Pentoxifylline therapy: A new adjunct in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:190–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehrotra R, Singh HP, Gupta SC, Singh M, Jain S. Pentoxifylline therapy in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:971–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhadage CJ, Umarji HR, Shah K, Välimaa H. Vasodilator isoxsuprine alleviates symptoms of oral submucous fibrosis. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:1375–82. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0824-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta D, Sharma SC. Oral submucous fibrosis – A new treatment regimen. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:830–3. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnamoorthy B, Khan M. Management of oral submucous fibrosis by two different drug regimens: A comparative study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2013;10:527–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James L, Shetty A, Rishi D, Abraham M. Management of oral submucous fibrosis with injection of hyaluronidase and dexamethasone in grade III oral submucous fibrosis: A Retrospective study. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:82–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah P, Venkatesh R, More C, Vassandacoumara V. Comparison of therapeutic efficacy of placental extract with dexamethasone and hyaluronic acid with dexamethasone for oral submucous fibrosis – A retrospective analysis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC63–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/20369.8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katharia S, Singh S, Kulshreshtha V. The effects of placenta extract in management of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Pharm. 1992;24:181–3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ali F, Khare A, Bai P, Dungrani H, Purohit J, Kumar S. A comparative study of drug regimen of dexamethasone, hyaluronidase and placental extract with triamcinolone acetonide, hyaluronidase and placental extract in the intralesional injection treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. J Res Adv Dent. 2015;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jirge V, Shashikanth M, Ali I, Anshumalee N. Levamisole and antioxidants in the management of oral submucous fibrosis: A comparative study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2008;20:135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haque MF, Meghji S, Nazir R, Harris M. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) may reverse oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:12–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goel S, Ahmed J. A comparative study on efficacy of different treatment modalities of oral submucous fibrosis evaluated by clinical staging in population of Southern Rajasthan. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:113–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.139263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta J, Srinivasan S, Jonathan D. Efficacy of betamethasone, placental extract and hyaluronidase in the treatment of OSMF. E J Dent. 2012;2:132–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shetty P, Shenai P, Chatra L, Rao PK. Efficacy of spirulina as an antioxidant adjuvant to corticosteroid injection in management of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24:347–50. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.118001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulk BS, Deshpande P, Velpula N, Chappidi V, Chintamaneni RL, Goyal S, et al. Spirulina and pentoxyfilline – A novel approach for treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:3048–50. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/7085.3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alam S, Ali I, Giri KY, Gokkulakrishnan S, Natu SS, Faisal M, et al. Efficacy of Aloe vera gel as an adjuvant treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116:717–24. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudarshan R, Annigeri RG, Sree Vijayabala G. Aloe vera in the treatment for oral submucous fibrosis – A preliminary study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:755–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox S, Zoellner H. Physiotherapeutic treatment improves oral opening in oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:220–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spencer AJ. An evidence-based approach to the prevention of oral diseases. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1159/000069846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: A systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–22. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoomans T, Ament AJ, Evers SM, Severens JL. Implementing guidelines into clinical practice: What is the value? J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:606–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]