Abstract

Regenerative medicine encompasses new emerging branch of medical sciences that involves the functional restoration of tissues or organs caused by severe injuries or chronic diseases. Currently, there are two contending technologies that can repair and restore the damaged tissues, namely platelet-rich plasma (PRP)- and stem cell (SC)-based therapies. PRP is a component of blood that contains platelet concentrations above the normal level and includes platelet-related growth factors and plasma-derived fibrinogen. Platelets are the frontline healing response to injuries as they release growth factors for tissue repair. SCs, on the other hand, are the unspecialized, undifferentiated, immature cells that based on specific stimuli can divide and differentiate into specific type of cells and tissues. Differentiated SCs can divide and replace the worn out or damaged tissues to become tissue- or organ-specific cells with specialized functions. Despite these differences, both approaches rely on rejuvenating the damaged tissue. This review is focused on delineating the preparation procedures, similarities and disparities and advantages and disadvantages of PRP- and SC-based therapies.

Keywords: Platelet-rich plasma, regeneration, stem cells, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Regenerative medicine is a major part of the rapidly emerging biomedical research over the last decade which mainly involves the development of new therapeutic strategies resulting in greater advancement in the field. These recent biomedical approaches have provided the tenacity for medical community to look for alternatives to conventional therapies. Among the several therapeutic strategies available, the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and stem cell (SC) represents the mainstream technologies to repair and rejuvenate the damaged tissue caused due to injury or chronic diseases.[1] PRP is the component of the blood (plasma) which contains five times higher concentrations of platelets above the normal values, i.e., PRP is the volume of autologous plasma that has the platelet concentration above the baseline.[2] Platelets are the tiny components of blood that are rich in growth factors and play a crucial role by forming blood clots during injury. It is a well-known fact that wound healing of damaged tissues depends on the platelet concentrations. PRP acts by nurturing those cells that can heal on their own or can augment the healing process by the resolution of damaged tissues. One of the widely used applications of PRP is in the regeneration and reconstruction of skeletal and connective tissues in the periodontal and maxillofacial diseases and in sports-related injuries.[3,4] Unlike PRP, SCs are the primitive cells that are obtained either from embryos or from the adult tissues. SC has the capacity of self-renewal and can differentiate into as many as 200 different cell types of the adult body.[5] Besides these properties, SC also produces certain growth factors and cytokines that accelerate the healing process at the site of tissue damage. Therapeutic applications of SC include treating many degenerative and inflammatory conditions by replacing the damaged cells in virtually any tissue or organ, where PRP applications serve no benefit.

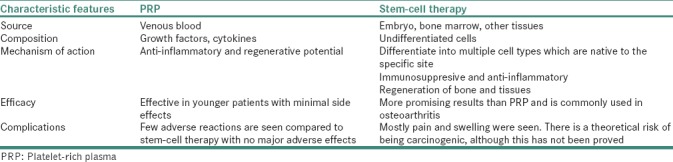

Although both PRP- and SC-based therapies are destined to perform similar functions in restoring the damaged tissue to function normally, there exists a vast difference in their preparation procedures and their functionality [Table 1]. SC is isolated from the adult tissues and cultured in sophisticated settings and requires several weeks to grow before they could be used for therapeutics. Contrary to SC, preparation of PRP is simple and involves rapid separation from blood and does not contain SCs for therapeutics per se. Furthermore, compared to SC-based therapies, the curative potential of PRP is considerably lower and regenerative potential is limited to the cells present in such tissues. Due to the similarity in function and the rapid preparations of PRP, several clinicians persuade patients to prefer PRP-based approaches citing that it is similar to SC-based therapies. Considering the existence of such a paradigm between the use of PRP- and SC-based technologies, future research should focus on understanding and clearly defining the molecular mechanism in tissue regeneration. In addition, efficacy and the perseverance of preparative methods, consensus in the preparation methods among different research groups for clinical applications and the significance of such technologies as a substitute for conventional therapies should be delineated and appropriately implemented.[4]

Table 1.

The differences between platelet-rich plasma and stem-cell therapy

PLATELET-RICH PLASMA

The term PRP was introduced in the 1970s to describe the autologous preparations and enrichment of platelets from plasma concentrate.[6] Platelets also known as thrombocytes are produced from megakaryocytes in mammalian bone marrow.[7] They form a first line of cellular defense response following damage to vascular and tissue integrity and play a crucial role in homeostasis, innate immunity, angiogenesis and wound healing.[8,9,10] Under normal conditions, the typical blood samples contain approximately 94% of red blood cells (RBCs), 6% of platelets and 1% of white blood cells. The whole purpose of enriching for PRP is to reverse the RBC-to-platelet ratio to achieve 95% platelets and 5% of RBCs.[11] Enriched fraction of PRP is known to contain high level of growth factors and cytokines that promote tissue regeneration and healing and also reported to be effective in tissue reparative efficacy.[12]

The primary roles of platelets are to form aggregated and also contribute to homeostasis through adhesion, activation and aggregation. Previously, platelets were thought to have only hemostatic activity. However, recent advancement has provided a new perspective on platelet function in regulating inflammation, angiogenesis, SC migration and cell proliferation.[6] Although many studies have supported the beneficial effects of using PRP, the Food and Drug Administration approval for injections of PRP is still under consideration. The only adverse reaction reported is transient pain and localized swelling after injections, but the overall adverse reactions being very low. Further studies are required to assess the efficacy of use of PRP for therapy and its possible long-term adverse reactions.

Major factors in platelet-rich plasma

Platelets play an important role in healing at the site of injury. The increased number of platelets results in increased number of secreted growth factors, thereby increasing the healing process. This phenomenon is attributed as it promotes mitogenesis of healing capable cells and angiogenesis in the tissues. Along with the presence of growth factors, they also contain adhesion molecules that include fibrin, fibronectin and vitronectin which help promote bone formation.[13,14] PRP preparations also play a role in revascularization of damaged tissue by promoting cell migration, proliferation, differentiation and stabilization of endothelial cells in new blood vessels. PRP also restores damaged connective tissue by promoting the migration, proliferation and activation of fibroblasts.[15,16] Platelets also host a vast reservoir of over 800 proteins which when secreted act upon SCs, fibroblasts, osteoblasts and endothelial and epithelial cells.[12] The main purpose of using PRP for therapeutics originated from the idea to deliver the growth factors, cytokines and α-granules to the site of injury, which acts as cell cycle regulators, and promote healing process across variety of tissues.[8]

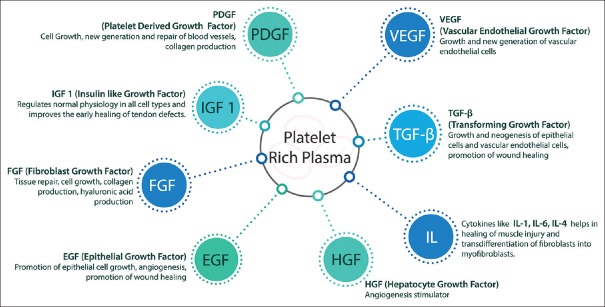

The PRP preparations are known to contain many growth factors, chemokines and cytokines [Figure 1] which induce the downstream signaling pathways that ultimately lead to synthesis of proteins necessary for collagen, osteoid and extracellular matrix formation.[17] PRP also has numerous cell adhesion molecules including fibrin, fibronectin, vitronectin and thrombospondin that trigger the assimilation of osteoblasts, fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Apart from its role in structural and functional healing, PRP preparations are also been implicated in the reduced use of narcotics, improved sleep and reduction in pain perception.[6,18,19]

Figure 1.

The components of platelet-rich plasma and their functions

PREPARATION OF PLATELET-RICH PLASMA

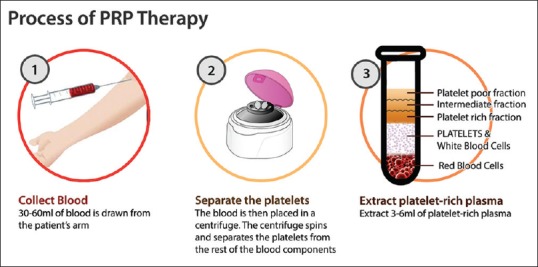

Preparation of PRP for regeneration of tissues includes three sequential steps – blood collection, PRP separation and PRP activation. Briefly, blood is collected using the anticoagulant agent preferably using acid citrate dextrose. The blood is then centrifugation using highly variable protocols with varying time (4–20 min), velocities (100–3000 ×g), temperature (12°C–26°C) and cycles of centrifugation (1 or 2 cycles). Due to these variable protocols, the platelet concentrations are enriched anywhere between 5 and 9 times. After centrifugation, the blood is separated into three layers – the bottom layer (RBCs), middle layer (platelets and white blood cells) and top layer (plasma with gradient of platelet concentrations) [Figure 2].[11,15]

Figure 2.

The procedure of separation of platelet-rich plasma from the venous blood

Considering different parameters and clinical applications, PRP is further classified base on four categories: activated, nonactivated, leukocyte rich and leukocyte poor. Activated PRP is prepared with calcium chloride with or without thrombin, which leads to release of cytokines from the granules in platelets. Nonactivated PRP preparations include platelet contact with intrinsic collagen and thromboplastin, which activate the platelets within connective tissue. In addition, the presence of leukocytes plays a role in inhibiting bacterial growth by improving soft-tissue healing, which would have been hindered by infection.[13] Magalon in 2016 proposed a DEAP classification which is based on dose, efficiency, purity and activation of platelets.[6] Further studies have been carried out to characterize and classify PRP based on preparation (centrifugation and use of anticoagulant), content (platelets, leukocytes and growth factors) and clinical applications. Studies by Dohan Ehrenfest et al. have proposed PRP classifications based on the presence and absence of leukocytes and fibrin architecture.[20]

Pure PRP: Preparations show low-density fibrin network after activation

Leukocyte- and PRP: Preparations contain leukocytes and exhibit low-density fibrin network after activation

Pure platelet-rich fibrin: Preparations lack leukocytes and have high-density fibrin network and exist in activated gel form

Leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin: Preparations have leukocytes with high-density fibrin network.

Clinical applications of platelet-rich plasma

Over the last few years, the use of PRP as a therapeutic tool has made a significant advancement in the field of regenerative medicine particularly in the field of wound healing and skin regeneration, dentistry, cosmetic and plastic surgery, fat grafting, bone regeneration, tendinopathies, ophthalmology, hepatocyte recovery, esthetic surgery, orthopedics, soft-tissue ulcers and skeletal muscle injury and others.[8]

As PRP contains high concentrations of growth factors, it is widely used for hair regrowth. These growth factors promote hair regrowth by binding to their respective receptors expressed by SCs of the hair follicle bulge region and associated tissues.[12]

The application of PRP in dermatology has increased in tissue regeneration, wound healing, scar revision and skin rejuvenating effects. PRP has rich source of growth factors that promote mitogenic, angiogenic and chemotactic properties; it has been used for the treatment of recalcitrant wounds. In cosmetic dermatology, PRP is known to stimulate human dermal fibroblast proliferation and increase type I collagen synthesis. In addition, injections of PRP into deep dermal layers have induced soft-tissue augmentation, activation of fibroblasts, new collagen deposition, new blood vessels and adipose tissue formation. Studies have also shown that PRP along with other techniques has improved the quality of the skin and leads to an increase in collagen and elastic fibers.[6]

PRP has also been used predominantly for musculoskeletal regeneration caused during sports injury. Acute hamstring for injuries accounts for approximately 29% of all sports-related injuries where PRP-based treatments have shown beneficial effects. Patellar tendinopathy also known as jumper's knee is the most common cause of anterior knee pain among athletes. Application of PRP is known to promote repair and reduce inflammation.[6] Achilles tendinopathy is another sports injury associated with severe pain and swelling at the tendinous insertion site. The rupture might get worse without proper treatment. Currently, muscle-strengthening exercise and anti-inflammatory medications are the only treatment options. The use of PRP was proposed as a treatment option.[13]

Osteoarthritis is one of the most common knee disorders which are commonly seen in elderly people due to cartilage damage and inflammatory changes. Several meta-analysis conducted on the these patients using both leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor PRP has displayed the benefits in favor of using PRP for osteoarthritis. PRP is known to stimulate chondrocytes and synoviocytes to produce cartilage matrix. In rotator cuff tear, which is the most common cause of shoulder disability, the inclusion of PRP-based therapy has beneficial effects for tendinous injuries. However, further clinical trials and metadata analysis are required for the clinical use of PRP as effective treatment technologies.[13] Apart from these diseases, PRP has also known to suppress the growth of particular species of bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus.[21] It is also shown to improve endometrial thickness in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment.[22]

In conclusion, there is an increase in the evidence that shows the beneficial use of platelet-based applications in tissue regeneration. However, there is considerable debate on the effectiveness of platelet-based applications, especially between human- and animal-based studies which could be due to the methodological differences among different research groups. There is a tremendous possibility for exploration in regenerative medicine which could use PRP for potential therapeutic applications.

Merits of platelet-rich plasma/advantages of platelet-rich plasma

The major advantage of the use of PRP for therapeutic applications is the immediate preparation of PRP, which does not require any preservative facilities. PRP is considered safe and natural as the preparation involves using own cells without any further modifications. This also ensures that the preparations do not elicit immune response. Since the preparations are from the same person, the chances of getting the bloodborne contaminations are minimized. As a large number of populations succumb to musculoskeletal injuries or disorders, application of PRP-based therapies has shown promising results.[11,23]

Demerits of platelet-rich plasma/disadvantages of platelet-rich plasma

The use of PRP as such does not have major demerits. However, under certain circumstances, PRP applications can result in injection-site morbidity, infection or injury to nerves or blood vessels. Scar tissue formation and calcification at the injection site have also been reported. Some patients have also experienced acute ache or soreness at the site of injection and also in the muscle or deeper areas such as the bone. Patients with compromised immune system or with predisposed diseases are more susceptible to infection at the injured area. Studies have reported allergic reactions among few individuals who have taken PRP-enriched fractions. Since PRP is given intravenously, the chances of damaging the artery or veins which could result in blood clot exist. Studies have also advised against using PRP-based therapies among individuals with a history of heavy smoking and drug and alcohol use and patients diagnosed with platelet dysfunction syndromes, thrombocytopenia, hyperfibrinogenemia, hemodynamic instability, sepsis, acute and chronic infections, chronic liver disease, anticoagulation therapy, chronic skin diseases or cancer and metabolic and systemic disorders due to the complications associated with the PRP-based treatment.[11]

STEM-CELL THERAPY

Recent advancement in the SC research has emphasized on the use of adult SC (ASC)-based therapies, which were not cured by conventional medicines. Tissue-resident adult progenitor SCs have clinical importance due to their potential cell sources for transplantation in regenerative medicine and cancer therapies. The ability for indefinite self-renewal and multilineage differentiation into other types of cells represents SCs, which offers great promise in replacing the nonfunctional or lost cells to regenerate damaged or diseased tissues.[24] The use of small subpopulation of adult stem or progenitor cells from tissues or organs from the same individual provides the possibility of stimulating those in vivo differentiation or cell replacement and gene therapies with multiple applications in humans without the risk of graft rejection. Research on tissue-resident SCs has explored the clinical interest in cell replacement-based therapies in regenerative medicine and cancer therapies.[25]

Type and source of stem cells

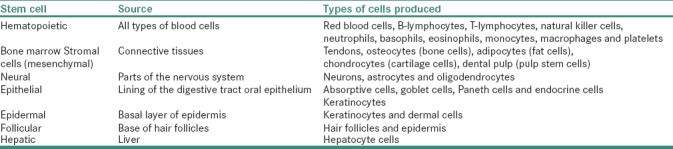

Based on their origin, SCs are divided into two types – embryonic SCs (ESCs) and ASCs. ESCs are derived from epiblast of the blastocyst from which many tissues of embryo arise, whereas ASCs are localized in adult organs [Table 2] where these cells function to replace damaged cells during tissue regeneration.[26,27] SCs are further classified into four types based on their transdifferentiation potential which include – totipotent, pluripotent, multipotent and unipotent SC.[24] ESCs are known to have totipotent and pluripotent in nature and have the ability to differentiate into cells of three germ layers – endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm.[28] ASC is multipotent and can give rise to differentiated cells of anyone germ layer.[29] Unipotent SCs arise from multipotent cells and are dedicated to differentiate into specific type of tissue, for example, precursors for cardiomyocytes present in human heart or satellite cells characteristic for skeletal muscles are dedicated to differentiate into specific tissue.[30]

Table 2.

Source and Type of cells produced from a normal adult stem cells

Isolation and culture of stem cell

The use of SCs for therapeutic purposes was proposed as early in the 1960s because of their inherent ability to differentiate into multiple cell lines.[17] This requires careful isolation and culturing which has to be done in aseptic condition. SCs are extracted either from bone marrow or fat tissue and are sometimes used in conjunction with platelets. Once isolated, SCs can retain their ability to transform into a variety of cell types. So far, there is no standardized procedure to isolate and to characterize SCs; however, specific markers are available to identify them.[31] Mesenchymal SCs (MSCs) are extensively studied cell types in regenerative medicine due to their immunomodulatory properties.[32] Studies have shown that MSC has the capacity to differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes, myocytes and cells of chondrogenic lineage.[17] MSCs express markers that include CD73, CD90 and CD105 (endoglin) but not CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD79a and human leukocyte antigen Class II.[33] Hematopoietic SCs express two important hematopoietic markers, i.e., CD45 and CD34.[34] Certain markers have been used as pluripotent markers such as OCT4, NANOG and SOX2. OCT4 is a transcriptional factor involved in early embryogenesis and very much essential for maintenance of pluripotency of SCs.[35] NANOG is a transcription factor and is involved in self-renewal capacity of undifferentiated SCs and has the ability to form any cell type of three germ layers of human body.[36,37] The third pluripotency gene is sex-determining region SOX2 which is also a transcription factor and maintains self-renew capacity of undifferentiated SCs.[38]

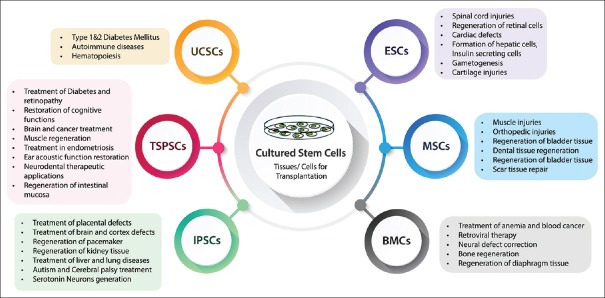

Clinical applications of stem cell

Although the use of SC has immense medical benefits, their applications in many diseases are still in the research and clinical trial phase and further studies are required for its long-term use in clinical settings. SCs have much more potent regulatory role in immune system. Compared to PRP-based approach, SC therapy can be very promising in treatment of many degenerative diseases where PRP is not suitable. SCs are also been used to treat many dental-related disorders such as regeneration and reconstruction of dental and oromaxillofacial tissues.[39,40] MSCs have shown to support blood and lymphangiogenesis and also shown to act as precursors of endothelial cells and pericytes and promote angiogenesis.[41] MSCs are known to orchestrate wound repair by cellular differentiation, immune modulation and production of growth factors that drive neovascularization and re-epithelialization [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

The promise of stem-cell therapy in regenerative medicine

Advantages of stem cell/merits of stem cell

SC-based therapies are emerging as a powerful tool for treating many degenerative and inflammatory diseases. Apart from differentiating into new tissue that is lost, they also coordinate in repair response. SC can be isolated from patients and can be amenable to autologous transplantation. Treatment with single isolation can provide lifetime repository of cells for the patients. Furthermore, SC can be genetically modified to overexpress crucial genes that can augment wound healing and decrease the formation of scars.[42]

Demerits of stem cell/disadvantages of stem cell

Although SC has added advantage over PRP-based approach in regenerating the damaged tissue, there are certain concerns in using SC for therapies. SC propensity toward self-renewal and differentiation is highly influenced by their local environment making it difficult to interpret how a population of culture expands MSC may behave in vivo. Isolation and characterization of SC are crucial and even the isolated SC may have low survival rates. Culturing of SC without contamination requires highly experienced personnel and sophisticated laboratory settings. The chances of microbial contamination of SC might result in complications, especially in those patients whose immune system is compromised. Careful monitoring and observation of this cell-based therapy are of paramount importance, since evidence has shown that adipose-derived MSCs have lost genetic stability over time and were prone to tumor formation.[43] Based on the specific application, SC should be differentiated into appropriate cell types before they can be clinically used, failure of which may have deleterious effects. Furthermore, SC-based therapies require regular follow-up to monitor regenerated tissue over a period of complete recovery of a patient. In vivo niches, SCs are present under hypoxic conditions and change in oxygen levels can induce oxidative stress, which can influence SC phenotype, proliferation, fate, pluripotency, etc., Therefore, in vitro culture conditions used to study MSCs should be maintained similar to their in vivo niches.[44]

Combinational therapy using both platelet-rich plasma injections and stem-cell therapy

PRP and SC therapy is continuously studied for their regenerative benefit in wound healing, sports medicine and chronic pain treatment. Although their preparation, mechanism and action and efficacy have been shown to be different, studies have shown that both PRP and SC can complement each other and might have an added advantage when used in combination. For example, PRP offers a suitable microenvironment for MSCs to promote proliferation and differentiation and accelerates wound healing capabilities. Conversely, PRP can be a powerful tool to attract cell populations, such as MSCs, a combination of which provides a promising approach for the treatment.[45] Some of the common injuries that are treated using combinational therapy include – tendonitis, rotator cuff tears, osteoarthritis, spine conditions, arthritic joints, overuse injuries, inflammation from herniated disc and others.[46,47]

CONCLUSION

Despite many beneficial effects of PRP in treating clinical conditions and with minimal side effects, the use of PRP as a regenerative medicine is still in its infancy. The major constraint is the limited availability of adequate controlled clinical trials and lack of consensus related to PRP preparation techniques. Nevertheless, the use of PRP-based preparations has shown promising results in some clinical settings, especially in the field of dermatology, dentistry, ophthalmology, orthopedics and others. Future research has to be focused on understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in the PRP-based therapies in tissue regeneration and long-term side effects associated with the use of PRP. Optimum concentration required to attain maximum tissue regeneration response without eliciting the immune response has to be determined. Investigating these key questions would increase the use of PRP-based regenerative medicines in treating acute and chronic ailments rather than using conventional therapies which would include surgeries followed by prolonged supportive therapies.

Although PRP and SC represent a promising treatment for many diseases, large-scale clinical trials using both in vitro and in vivo studies are required to establish the true effectiveness of the treatments. SC-based therapies have shown promising results in clinical settings, and further work should be carried out to optimize the transplantation procedures that ensure functional integration, proliferation, differentiation and migration of transplanted tissue-specific ASCs to repair and replace the damaged tissue and their long-term survival in the tissue niche.

In conclusion, PRP-based therapeutic option could be used as an alternative form of therapy alone or in combination with other conventional treatments. In this regard, it is important to understand the formulations and specific enrichment fractions that could be suitable for particular treatment. Furthermore, research has to focus on standardizing the PRP formulations and have a consensus data from the clinical trials from different research groups for better prognosis and to use as an alternative to conventional therapies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lysaght MJ, Crager J. Origins. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1449–50. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: Evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsousou J, Ali A, Willett K, Harrison P. The role of platelet-rich plasma in tissue regeneration. Platelets. 2013;24:173–82. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.684730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redler LH, Thompson SA, Hsu SH, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Platelet-rich plasma therapy: A systematic literature review and evidence for clinical use. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39:42–51. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.02.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godberg M, editor. The Dental Pulp: Biology, Pathology, and Regenerative Therapies Edited by Michel Goldberg. Ch. 16. France: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2014. Pulp stem cells: Niche of stem cells; pp. 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietrzak WS, Eppley BL. Platelet rich plasma: Biology and new technology. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:1043–54. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000186454.07097.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naik B, Karunakar P, Jayadev M, Marshal VR. Role of platelet rich fibrin in wound healing: A critical review. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:284–93. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.114344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currie LJ, Sharpe JR, Martin R. The use of fibrin glue in skin grafts and tissue-engineered skin replacements: A review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1713–26. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200111000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawase T, Okuda K, Wolff LF, Yoshie H. Platelet-rich plasma-derived fibrin clot formation stimulates collagen synthesis in periodontal ligament and osteoblastic cells in vitro . J Periodontol. 2003;74:858–64. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christgau M, Moder D, Hiller KA, Dada A, Schmitz G, Schmalz G, et al. Growth factors and cytokines in autologous platelet concentrate and their correlation to periodontal regeneration outcomes. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:837–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyras DN, Kazakos K, Agrogiannis G, Verettas D, Kokka A, Kiziridis G, et al. Experimental study of tendon healing early phase: Is IGF-1 expression influenced by platelet rich plasma gel? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Intwala AR, Baudino TA. IL-6 loss causes ventricular dysfunction, fibrosis, reduced capillary density, and dramatically alters the cell populations of the developing and adult heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1694–704. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00908.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seong GJ, Hong S, Jung SA, Lee JJ, Lim E, Kim SJ, et al. TGF-beta-induced interleukin-6 participates in transdifferentiation of human Tenon's fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2123–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhillon RS, Schwarz EM, Maloney MD. Platelet-rich plasma therapy – Future or trend? Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:219. doi: 10.1186/ar3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: From pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte – And platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:158–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheth U, Simunovic N, Klein G, Fu F, Einhorn TA, Schemitsch E, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma use for orthopaedic indications: A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:298–307. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomoyasu A, Higashio K, Kanomata K, Goto M, Kodaira K, Serizawa H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates osteoblastic differentiation in the presence of BMPs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X, Ren J, Yuan Y, Luan J, Yao G, Li J, et al. Antimicrobial properties of single-donor-derived, platelet-leukocyte fibrin for fistula occlusion: An in vitro study. Platelets. 2013;24:632–6. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.761685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gimbrone MA, Jr, Aster RH, Cotran RS, Corkery J, Jandl JH, Folkman J, et al. Preservation of vascular integrity in organs perfused in vitro with a platelet-rich medium. Nature. 1969;222:33–6. doi: 10.1038/222033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang Y, Li J, Chen Y, Wei L, Yang X, Shi Y, et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma promotes endometrial growth and improves pregnancy outcome during in vitro fertilization. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:1286–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang-Saegusa A, Cugat R, Ares O, Seijas R, Cuscó X, Garcia-Balletbó M, et al. Infiltration of plasma rich in growth factors for osteoarthritis of the knee short-term effects on function and quality of life. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:311–7. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Last accessed on 2011 Jun 06]. Available from: http://www.uscenterforsportsmedicine.com/whatarethe-side-effects-of-platelet-rich-plasma-therapy .

- 23.Bianco P, Robey PG, Simmons PJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: Revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otsu K, Kumakami-Sakano M, Fujiwara N, Kikuchi K, Keller L, Lesot H, et al. Stem cell sources for tooth regeneration: Current status and future prospects. Front Physiol. 2014;5:36. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deepak P, Dhirendra S, Sonal M, Subha RD, Gagan M, Pranshu S. Stem cells in dental and maxillofacial surgery: An overview. EJDTR. 2014;3:195–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong L. Epigenetic control of embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telles PD, Machado MA, Sakai VT, Nör JE. Pulp tissue from primary teeth: New source of stem cells. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:189–94. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000300002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng HH, Surani MA. The transcriptional and signalling networks of pluripotency. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:490–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alison MR, Islam S. Attributes of adult stem cells. J Pathol. 2009;217:144–60. doi: 10.1002/path.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosio A, Bissels U, Miltenyi S. Characterization and classification of stem cells. In: Steinhoff G, editor. Regenerative Medicine: From Protocol to Patient. Germany: Springer Science+Business Media BV; 2011. pp. 149–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potdar PD, Jethmalani YD. Human dental pulp stem cells: Applications in future regenerative medicine. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7:839–51. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i5.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avinash K, Malaippan S, Dooraiswamy JN. Methods of isolation and characterization of stem cells from different regions of oral cavity using markers: A Systematic review. Int J Stem Cells. 2017;10:12–20. doi: 10.15283/ijsc17010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garikipati VN, Singh SP, Mohanram Y, Gupta AK, Kapoor D, Nityanand S, et al. Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human fetus heart. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Boeck A, Narine K, De Neve W, Mareel M, Bracke M, De Wever O, et al. Resident and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:336–42. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Blanc K. Immunomodulatory effects of fetal and adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:485–9. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satterthwaite AB, Burn TC, Le Beau MM, Tenen DG. Structure of the gene encoding CD34, a human hematopoietic stem cell antigen. Genomics. 1992;12:788–94. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90310-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ. P53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF. Nature. 2007;450:721–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–6. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, et al. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lozito TP, Kuo CK, Taboas JM, Tuan RS. Human mesenchymal stem cells express vascular cell phenotypes upon interaction with endothelial cell matrix. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:714–22. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sankaranarayanan S, Ramachandran C, Padmanabhan J, Manjunath S, Baskar S, Senthil Kumar R, et al. Novel approach in the management of an oral premalignant condition – A case report. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2007;3:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duailibi MT, Duailibi SE, Young CS, Bartlett JD, Vacanti JP, Yelick PC, et al. Bioengineered teeth from cultured rat tooth bud cells. J Dent Res. 2004;83:523–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen M, Przyborowski M, Berthiaume F. Stem cells for skin tissue engineering and wound healing. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;37:399–421. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v37.i4-5.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher JN, Peretti GM, Scotti C. Stem cells for bone regeneration: From cell-based therapies to decellularised engineered extracellular matrices. Stem Cells Int 2016. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/9352598. 9352598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rubio D, Garcia-Castro J, Martín MC, de la Fuente R, Cigudosa JC, Lloyd AC, et al. Spontaneous human adult stem cell transformation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3035–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balaji S, Keswani SG, Crombleholme TM. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in the regenerative wound healing phenotype. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2012;1:159–65. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahmoudian-Sani MR, Rafeei F, Amini R, Saidijam M. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells combined with platelet-rich plasma on skin wound healing. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:650–9. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]