Abstract

Background: This study examined interrelationships of selected interleukins (ILs), tumor growth factors, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and C-reactive protein, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) with lymphedema/fibrosis in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC).

Methods and Results: Patients newly diagnosed with ≥Stage II HNC (N = 100) were assessed for external/internal lymphedema and/or fibrosis before treatment, end-of-treatment, and at regularly established intervals through 72 weeks posttreatment and blood was drawn. Data from 83 patients were analyzed. Group-based trajectory modeling generated patient groups with similar longitudinal biomarker and lymphedema–fibrosis trajectories. Area-under-the-curve (AUC) values were also generated for each biomarker and severity of lymphedema–fibrosis. Associations among and between biomarkers and lymphedema–fibrosis trajectories and AUCs were tested (log-likelihood chi-square, correlations). The strongest evidence for the association of biomarkers with the overall and trajectory patterns and severity of lymphedema–fibrosis was observed for IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, TGF-β1, and MMP-9 (all p < 0.05). Convergence of joint trajectory patterns and AUC were observed with IL-6 with all lymphedema–fibrosis trajectories and internal lymphedema AUC. IL-1β trajectories converged with external lymphedema trajectories and all lymphedema–fibrosis AUCs. TNF-α and TGF-β1 converged most strongly with fibrosis in terms of trajectory patterns. However TNF-α demonstrated stronger association with lymphedema–fibrosis AUC (fibrosis: rs = 0.49). MMP-9 demonstrated convergence with lymphedema–fibrosis AUCs (lymphedema: 0.43–0.42; fibrosis: 0.35).

Conclusion: Systemic levels of selected mediators of proinflammatory processes track with acute and chronic clinical phenotypes of lymphedema/fibrosis in HNC patients suggesting their potential role in the pathogenesis of these conditions.

Keywords : cytokines, biomarkers, lymphedema, fibrosis, head and neck cancer

Introduction

Many of the 49,670 individuals diagnosed with cancers of the head and neck in 2017 will be successfully treated.1 Yet while they survive for several years, many will be saddled with long-term sequelae wrought by both their cancer and its treatment.2 Treatment of head and neck cancer (HNC) commonly involves an imposing regimen in which surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy may be used alone or in combination. Consequent tissue damage to the surrounding incision or radiation fields fosters a physiological environment in which fluid accumulation in both internal and external structures of the head and neck predisposes to soft tissue fibrosis.3–5 Lymphedema and fibrosis occur as a continuum that ranges from mild to severe and directly contributes to a number of clinical complications, such as swallowing and breathing difficulties, and functional impairment.5–8

Lymphedema and fibrosis are two of the most common, but poorly recognized side effects of HNC and its treatment.2,5,8 Posttreatment rates of external and internal lymphedema and fibrosis have been recently documented.5 Previous research has also identified two distinct clinical trajectories for external lymphedema, internal lymphedema, and fibrosis in this patient population that occur during the first 18 months postcancer treatment.5 One trajectory is characterized by none or a maximum of mild-grade abnormality throughout the entire posttreatment period (up to 18 months post); the second characterized by an escalation to moderate–severe grade abnormality between 6 and 12 months posttreatment with slight decline between 12 and 18 months. The trajectory for patients classified in the moderate–severe fibrosis pattern peak slightly later (>12 months post) than the lymphedema trajectories.

Despite their high prevalence and severity, surprisingly little is known about the pathogenesis, which underlies lymphedema and fibrosis in patients with HNC, although both animal and human data suggest the involvement of a range of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8.9–13 Additionally, the observation that increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity associated with filarial-induced lymphedema suggests a potential role in the development of the lymphedema phenotype, as does its interaction with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to contribute to skeletal abnormalities in the head and neck.14,15 Likewise, the finding that C-reactive protein (CRP) levels correlate with the severity of a range of infectious and chronic inflammatory disorders suggests its potential association with lymphedema and fibrosis.16,17

Given the relatively high rates of both lymphedema and fibrosis in this patient population, distinct clinical trajectories, and the limited knowledge regarding its pathogenesis, we undertook a longitudinal examination of potential biological mediators by evaluating the trajectory of selected cytokines, MMPs, and CRP using samples collected from initial diagnosis, throughout treatment and then 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 60, and 72 weeks thereafter. Our primary hypothesis was that we would be able to differentiate patterns of these proteins that correlated with the development of late-effect lymphedema and/or fibrosis in a patient with HNC.

Materials and Methods

Ethical aspects

This study was conducted as part of a parent study that had as its primary aim to determine the prevalence and nature of lymphedema and fibrosis in patients with HNC. Primary findings from the parent study have been previously published.5 Permission to conduct the parent research study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University and from the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) Scientific Review Committee in Nashville, TN. The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained before enrollment in the study.

Methods

Participants

Patients with newly diagnosed carcinoma of the head and neck were recruited at VICC. They were required to be undergoing treatment and have planned posttreatment follow-up at the study site. Additionally, the patients had to be ≥21 years of age, have Stage II or higher disease, and speak English. Individuals could not be in the study if their medical history indicated cognitive impairment or recurrent cancer of the head and neck.

Patients were seen before initiation of concomitant chemoradiation for baseline data collection. On the day of the baseline assessment, trained study staff collected demographic information and clinical history, completed a physical examination to determine the presence of external lymphedema and fibrosis, and drew preliminary blood specimens. Baseline internal lymphedema was ascertained during flexible fiberoptic endoscopic examination conducted by physicians. Subsequently, data were collected and blood was drawn at follow-up visits commencing at immediate end of treatment and 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 60, and 72 weeks posttreatment. With the exception of immediate end of treatment, endoscopic examinations were completed at all follow-up time points.

Data collection

Fibrosis and lymphedema

External lymphedema findings were documented using the American Cancer Society (ACS) Lymphedema of the Head and Neck staging criteria.18 The Patterson Scale was used to record findings from the endoscopic examination.19 Physical examination findings for fibrosis were documented using Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Fibrosis Scale (version 3).20

Blood

Trained study team members drew all the blood samples. The samples were taken to the on-site Vanderbilt Immunology Core for processing and storage. The immune core staff completed the analyses of all the biomarkers investigated in this study. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6, and IL-8 were analyzed using a sensitive flow cytometric bead array (Becton Dickinson) assay that allows multiple cytokine analyses of a single sample. Two-color flow cytometric analysis was performed using a LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). CRP, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, MMP-2, and MMP-9 were measured using electrochemiluminescence multiplex array technology from Meso-Scale Discovery (Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were acquired using a Sector 2400 imager.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Frequency distributions summarized nominal and ordinal data; mean and standard deviation summarized normally distributed continuous data, whereas median and interquartile range was used for skewed data. An alpha of 0.05 was used for determining statistical significance.

The most specific and targeted investigation of the concordance of the longitudinal patterns of a specific biomarker with the severity of lymphedema and fibrosis was the group-based trajectory approach. The results of that analysis for the severity of lymphedema and fibrosis have been published and as has two distinct, longitudinal patterns that were observed for each condition.5 Group-based trajectory modeling was applied to the longitudinal data collected for each of the biomarkers. For every biomarker, a two-group solution demonstrated the best fit to the data. The extent to which the patients in a group defined by a specific longitudinal pattern for biomarker (e.g., low at baseline, very high 3 months posttreatment, and then drop to moderate levels but never back to baseline at 1 year post) were likely to also be in the group defined by a similar longitudinal pattern for the severity of lymphedema and fibrosis (e.g., external lymphedema) could then be tested (joint probability using log-likelihood chi-square statistics).

A more global approach to assessing the extent of the associations between the biomarkers and severity of lymphedema and fibrosis used area-under-the-curve (AUC) summaries. These summaries do not speak to the specific patterns (e.g., high baseline and posttreatment and then low by1 year), rather they are an aggregate of the overall level of a biomarker or severity of lymphedema. Differences in AUC levels between the lymphedema and fibrosis trajectory groups were tested (Mann–Whitney) and biomarker AUC levels were correlated with lymphedema and fibrosis AUC levels (Spearman correlation).

Results

Patient characteristics

The sample (N = 83) consisted primarily of nonurban dwelling (59%), high school graduates (M = 13 years of education), who were male (72%), with a mean age of 57.8 years. The majority (>95%) had Stage III or IV cancer at the time of diagnosis and 97.6 underwent CCR treatment. Additional details are available in a previously published article.5

Biomarkers

Interleukins

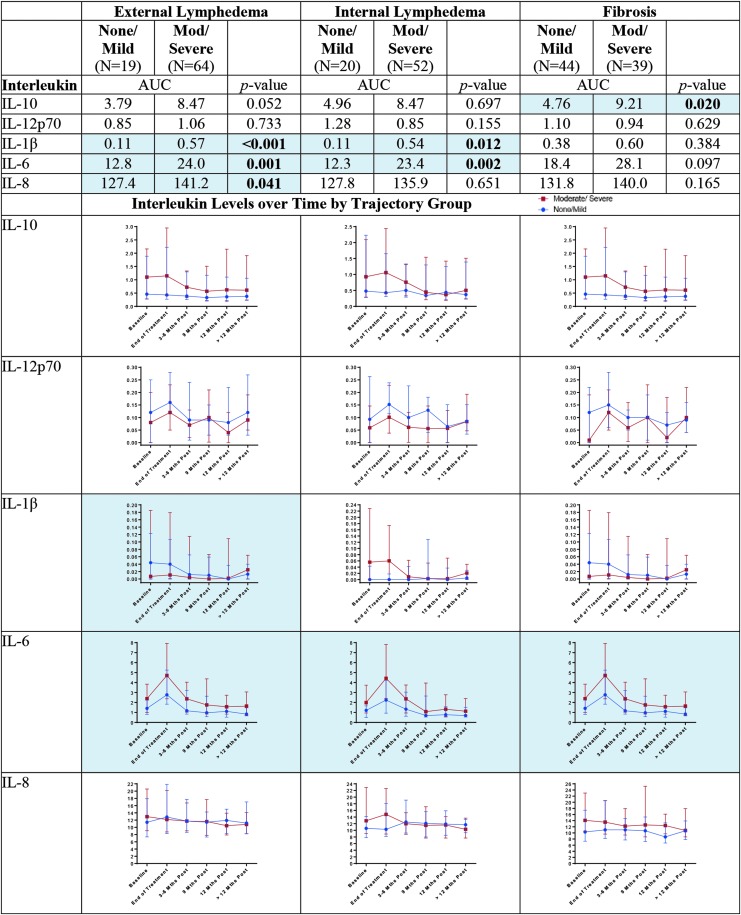

Results for the associations of the ILs with the severity of lymphedema–fibrosis are shown in Figure 1. The strongest effects were observed for IL-6 and IL-1β. The multiple approaches converged to demonstrate that patients with moderate–severe trajectories of internal lymphedema and those with moderate–severe trajectories of external lymphedema, had statistically significantly higher IL-6 AUCs (p < 0.01) and the elevation was consistent throughout the year-long posttreatment period (p < 0.05). While differences in IL-6 AUC were not statistically significant for the fibrosis trajectories (p = 0.097), concordance of the trajectories was observed with fibrosis (p < 0.05). Convergence of the multiple approaches was also observed for IL-1β with external lymphedema (AUC, p < 0.001, trajectory concordance, p < 0.05). Differences in the IL-1β AUC values were also observed between the internal lymphedema trajectory severity groups (p = 0.012). IL-10 AUC values were statistically significantly higher for the moderate–severe fibrosis trajectory group than those for the none/mild groups (p = 0.020). A similar, yet not statistically significant, concordance of the trajectories can be seen in the lower portion of Figure 1. Finally, statistically significantly higher AUC levels for IL-8 were observed for the moderate–severe external trajectory group compared with the none/mild (p = 0.041). A clear concordance of longitudinal trajectories was not observed, however (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Interleukins by trajectory group. Blue shading and bolding indicate p < 0.05.

Matrix metalloproteinases

Compared with patients with none–mild trajectories, statistically significantly higher MMP-9 AUC values were observed for groups of patients with moderate–severe external lymphedema trajectories (p = 0.003) and moderate–severe fibrosis trajectories (p = 0.045). As shown in Figure 2, patterns of concordance between the longitudinal patterns were not consistent and not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

FIG. 2.

Matrix metalloproteinases by trajectory group. Blue shading and bolding indicate p < 0.05.

Transforming growth factors

Associations of TGFs with the lymphedema–fibrosis trajectories are shown in Figure 3. Statistically significantly lower TGF-β2 AUC values were observed for the patients with moderate–severe internal lymphedema trajectories compared with those with none/mild internal lymphedema (p = 0.028). As shown, there does appear to be a concordant pattern to the trajectories, yet that concordance was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). There was a concordance of the trajectories of TGF-β1 with the trajectory patterns of fibrosis (p < 0.05). In this case, the AUC values were not statistically significantly different, however (p > 0.05).

FIG. 3.

Transforming growth factors by trajectory group. Blue shading and bolding indicate p < 0.05.

Other biomarker

Among the additional biomarkers (interferon-gamma [IFN-γ], TNF-α, CRP), TNF-α demonstrated statistically significant associations with the severity of external lymphedema and with the severity of fibrosis. The multiple approaches converged for the association with fibrosis (Fig. 4), with the AUC values being higher for those in the moderate–severe trajectory group (p = 0.003) and concordance between the TNF-α and fibrosis trajectory groups (p < 0.05). Similar patterns of differences and concordance were observed for external lymphedema. The AUC differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001), yet the concordance findings were not (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Other cytokines by trajectory group. Blue shading and bolding indicate p < 0.05.

Discussion of Results

To the best of our knowledge this is the first known study to follow HNC patients up to 18 months after treatment and simultaneously collect biomarkers and assess lymphedema and fibrosis. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are similar to the overall HNC population in the United States.1,5 Thus, the findings may generalize to HNC patient populations outside the southeastern region of the country where the study was conducted.

Our results support the notion that an association exists between the levels of selected proinflammatory cytokines and the risk and course of clinically significant lymphedema and fibrosis among patients being treated with conventional regimens for cancers of the head and neck. For example, IL-6 levels were significantly higher at the immediate end-of-treatment for those who developed moderate–severe external and internal lymphedema and fibrosis compared with individuals with none– mild trajectories. These levels began a slow rise again at 12 months posttreatment suggesting the presence of persistent, treatment-induced inflammatory processes that are manifest months after cancer treatment has ended. Convergence of joint trajectory patterns and AUC were observed with IL-6 and all lymphedema–fibrosis trajectories and internal lymphedema AUC. These findings are supported by previous research that established IL-6 as a regulator of both adipose disposition and hemostasis in human lymphedema11 and murine work that identified IL-6 as an activate agent in collagen production.21

IL-1β levels were slightly higher at immediate end of treatment for those who developed moderate–severe external lymphedema and fibrosis than those with none–mild trajectories. These levels also began a slow rise again at 12 months posttreatment. IL-1β trajectories converged with external lymphedema trajectories and all lymphedema–fibrosis AUCs. This finding is consistent with earlier findings that IL-1β, a proinflammatory cytokine, upregulated by radiation, was indicated in radiation-induced skin fibrosis in vivo and in vitro.22

MMP-9 while not demonstrating statistically significant joint associations with lymphedema–fibrosis in terms of longitudinal trajectories, did demonstrate convergence with lymphedema–fibrosis AUCs. The finding that MMP-9 may play a role in lymphedema–fibrosis in this patient population is not surprising. MMPs have been implicated in multiple autoimmune diseases with inflammatory underlays, such as, coronary artery disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus.23,24 Additionally, these findings suggest that MMP-9 may be a common facilitator of lymphedema/fibrosis with both lymphedema secondary to cancer treatment, as in this study, or in lymphedema filariasis, as noted by Bennuru et al.25,26

TNF-α and TGF-β1 converged most strongly with fibrosis in terms of trajectory patterns; however, TNF-α demonstrated stronger associations of lymphedema–fibrosis AUC. TNF-α is produced in response to radiation and contributes to the influx of inflammatory cells to the alveoli and interstitium of the lungs, leading to fibrosis.27,28 TGF-β has been labeled a key agent in fibroproliferative conditions of the lung, kidney, liver, and skin. TGF-β1 levels postradiation therapy has been associated with radiation pneumonitis and progressive radiation-induced lung injury and pulmonary fibrosis.29–32 Increased quantities of TGF-β1 have been found in lung tissue of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and TGF-β1 is believed to support expansion of cells in filarial infections, which commonly present with lymphedema and fibrosis.33

TNF-α was most strongly associated with fibrosis in terms of trajectory patterns; however, TNF-α demonstrated stronger associations of lymphedema–fibrosis AUC. It is well documented that TNF-α is produced in response to radiation and contributes to the influx of inflammatory cells to the alveoli and interstitium of the lungs, leading to fibrosis.27,28 Thus, this finding is not surprising.

Conclusion

Proinflammatory processes clearly contribute to the development of lymphedema/fibrosis in patients who have experienced cancer of the head and neck. The processes continue well past end of treatment. The strongest evidence for the interrelationships of biomarkers with the overall and trajectory patterns of the severity of lymphedema–fibrosis was observed for IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, TGF-β1, and MMP-9.

Not surprisingly, our findings are broadly consistent with other studies which have demonstrated a relationship between the trajectory of cancer regimen-related toxicities and proinflammatory cytokine levels. Given the pathogenesis of tissue injury in response to radiation-based protocols (as well as with cytotoxic chemotherapy) and the pivotal role thought to be played by activation of NF-κB, the cytokines noted in this study are consistent with their roles in driving toxicity phenotypes. This finding reinforces the future consideration of using cytokines as dynamic biomarkers for lymphedema and fibrosis. The use of such biomarkers could facilitate identification of patients at high risk for severe lymphedema and fibrosis and pave the way for preventive interventional clinical trials. Additionally, prospective, longitudinal evaluation of these biomarkers in this patient population could provide actionable information during the course of, and following, cancer therapy, especially when more robust treatment interventions become available. Further research of these biomarkers is supported by our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the critically ill volunteers who spent a great deal of time and effort supporting this research. Primary funding for this study was provided by grant 1 R01 CA149113-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health. Equipments used in this study were partially supported equipment on loan through the Cancer Survivorship Research Core. The Cancer Survivorship Research Core is supported in part by grant 1UL 1RR024975 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Vanderbilt University. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources. REDCap is supported by the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research grant UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NI.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. Facts and Figures, 2017. 2017; Available at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf Accessed October17, 2017

- 2. Murphy BA, Gilbert J, Ridner SH. Systemic and global toxicities of head and neck treatment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2007; 7:1043–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith BG, Lewin JS. Lymphedema management in head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 18:153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deng J, Ridner SH, Wells N, Dietrich MS, Murphy BA. Development and preliminary testing of head and neck cancer related external lymphedema and fibrosis assessment criteria. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2015; 19:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Niermann K, Cmelak A, Mannion K, Murphy B. A Prospective study of the lymphedema and fibrosis continuum in patients with head and neck cancer. Lymphat Res Biol 2016; 14:198–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruns F, Buntzel J, Mucke R, Schonekaes K, Kisters K, Micke O. Selenium in the treatment of head and neck lymphedema. Med Princ Pract 2004; 13:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jackson LK, Ridner SH, Deng J, Bartow C, Mannion K, Niermann K, Gilbert J, Dietrich MS, Cmelak AJ, Murphy BA. Internal lymphedema correlates with subjective and objective measures of dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2016; 19:949–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rockson SG. Lymphedema in head and neck cancer. Lymphat Res Biol 2016; 14:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tabibiazar R, Cheung L, Han J, Swanson J, Beilhack A, An A, Dadras SS, Rockson N, Joshi S, Wagner R, Rockson SG. Inflammatory manifestations of experimental lymphatic insufficiency. PLoS Med 2006; 3:e254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bergeron A, Soler P, Kambouchner M, Loiseau P, Milleron B, Valeyre D, Hance AJ, Tazi A. Cytokine profiles in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis suggest an important role for TGF-beta and IL-10. Eur Respir J 2003; 22:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cuzzone DA, Weitman ES, Albano NJ, Ghanta S, Savetsky IL, Gardenier JC, Joseph WJ, Torrisi JS, Bromberg JF, Olszewski WL, Rockson SG, Mehrara BJ. IL-6 regulates adipose deposition and homeostasis in lymphedema. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014; 306:H1426–H1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Satapathy AK, Sartono E, Sahoo PK, Dentener MA, Michael E, Yazdanbakhsh M, Ravindran B. Human bancroftian filariasis: Immunological markers of morbidity and infection. Microbes Infect 2006; 8:2414–2423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaitanya GV, Franks SE, Cromer W, Wells SR, Bienkowska M, Jennings MH, Ruddell A, Ando T, Wang Y, Gu Y, Sapp M, Mathis JM, Jordan PA, Minagar A, Alexander JS. Differential cytokine responses in human and mouse lymphatic endothelial cells to cytokines in vitro. Lymphat Res Biol 2010; 8:155–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Couto RA, Kulungowski AM, Chawla AS, Fishman SJ, Greene AK. Expression of angiogenic and vasculogenic factors in human lymphedematous tissue. Lymphat Res Biol 2011; 9:143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balakrishnan K, Majesky M, Perkins JA. Head and neck lymphatic tumors and bony abnormalities: A clinical and molecular review. Lymphat Res Biol 2011; 9:205–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lal RB, Dhawan RR, Ramzy RM, Farris RM, Gad AA. C-reactive protein in patients with lymphatic filariasis: Increased expression on lymphocytes in chronic lymphatic obstruction. J Clin Immunol 1991; 11:46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dhingra R, Gona P, Nam BH, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, O'Donnell CJ. C-reactive protein, inflammatory conditions, and cardiovascular disease risk. Am J Med 2007; 120:1054–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Cancer Society. Lymphedema: Understanding and Managing Lymphedema After Cancer Treatment. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patterson JM, Hildreth A, Wilson JA. Measuring edema in irradiated head and neck cancer patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2007; 116:559–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). In: Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Washington, D.C.: National Institutes for Health; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin ZQ, Kondo T, Ishida Y, Takayasu T, Mukaida N. Essential involvement of IL-6 in the skin wound-healing process as evidenced by delayed wound healing in IL-6-deficient mice. J Leukoc Biol 2003; 73:713–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu W, Ding I, Chen K, Olschowka J, Xu J, Hu D, Morrow GR, Okunieff P. Interleukin 1β (IL1B) Signaling is a critical component of radiation-induced skin fibrosis. Radiat Res 2006; 165:181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ram M, Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and autoimmune diseases. J Clin Immunol 2006; 26:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mohammed FF, Smookler DS, Khokha R. Metalloproteinases, inflammation, and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62(Suppl 2):ii43–ii47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bennuru S, Nutman TB. Lymphatics in human lymphatic filariasis: In vitro models of parasite-induced lymphatic remodeling. Lymphat Res Biol 2009; 7:215–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bennuru S, Nutman TB. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic remodeling induced by filarial parasites: Implications for pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 2009; 5:e1000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fleckenstein K, Gauter-Fleckenstein B, Jackson IL, Rabbani Z, Anscher M, Vujaskovic Z. Using biological markers to predict risk of radiation injury. Semin Radiat Oncol 2007; 17:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnston CJ, Piedboeuf B, Rubin P, Williams JP, Baggs R, Finkelstein JN. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1α, interleukin-1ß and tumor necrosis factor a mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res 1996; 145:762–767 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 2008; 214:199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anscher MS, Thrasher B, Zgonjanin L, Rabbani ZN, Corbley MJ, Fu K, Sun L, Lee WC, Ling LE, Vujaskovic Z. Small molecular inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta protects against development of radiation-induced lung injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 71:829–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Decologne N, Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Menetrier F, Artur Y, Garrido C, Gauldie J, Camus P, Bonniaud P. TGF-β1 induces progressive pleural scarring and subpleural fibrosis. J Immunol 2007; 179:6043–6051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ask K, Bonniaud P, Maass K, Eickelberg O, Margetts PJ, Warburton D, Groffen J, Gauldie J, Kolb M. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis is mediated by TGF-beta isoform 1 but not TGF-beta3. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008; 40:484–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anuradha R, George PJ, Hanna LE, Chandrasekaran V, Kumaran P, Nutman TB, Babu S. IL-4-, TGF-beta-, and IL-1-dependent expansion of parasite antigen-specific Th9 cells is associated with clinical pathology in human lymphatic filariasis. J Immunol 2013; 191:2466–2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]