Abstract

Background: The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the association and directionality between mental health disorders and substance use among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. and Canada. Methods: The following databases were used: Medline, PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library. Meta-analysis used odds ratios as the pooled measure of effect. Results: A total of 3656 studies were screened and 36 were selected. Pooled results showed a positive association between depression and use of alcohol (odds ratio (OR) = 1.50, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.24–1.83), cannabis (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.10–1.51), and tobacco (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.43–1.92). Significant associations were also found between anxiety and use of alcohol (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.19–2.00), cannabis (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.02–1.81), and tobacco (OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.54–3.17). A bidirectional relationship was observed with tobacco use at baseline leading to depression at follow-up (OR = 1.87, CI = 1.23–2.85) and depression at baseline leading to tobacco use at follow-up (OR = 1.22, CI = 1.09–1.37). A unidirectional relationship was also observed with cannabis use leading to depression (OR = 1.33, CI = 1.19–1.49). Conclusion: This study offers insights into the association and directionality between mental health disorders and substance use among adolescents and young adults. Our findings can help guide key stakeholders in making recommendations for interventions, policy and programming.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, adolescents, young adults, U.S., Canada

1. Background

Mental health disorders and substance use are important problems and relatively common among adolescents and young adults [1]. These two conditions are the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide [2]. People are more likely to initiate substance use during adolescence, a critical period in one’s life as they transition from childhood to adulthood [3]. It is estimated that 50% of all mental health disorders start by the age of 14 years old and 75% by the age of 25 years old [4]. Mental health disorders and substance use problems are closely linked, and both conditions can share similar biological and environmental components [5,6].

Mental health disorders contribute significantly to the burden of disease [2]. Globally, approximately one in five adolescents experience a mental health disorder each year [7]. Depressive and anxiety disorders are quite prevalent among adolescents and young adults. In the U.S., 8.4% of adolescents were diagnosed with either anxiety or depression in their lifetime [8]. In Canada, 5% of adolescents were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and 6.3% with a mood disorder, mainly depression [9]. Despite the magnitude of the problem posed by mental health disorders among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. and Canada, frequently they are undiagnosed and when diagnosed not treated properly [10].

Adolescents and young adults with mental health disorders are at an increased risk of many negative health and social outcomes including self-harm and suicide [11], poor academic performance [12], and involvement in risky behaviors and poor sexual health [13]. It is reported that there is a link between adverse life events such as maltreatment and violence, loss, intra-familial problems, and school and interpersonal problems and suicidal behavior among young people. Also, the number of negative life events experienced by a young individual is reported to have a positive dose–response relation to suicidal behavior [14]. Risk factors for mental health disorders include biological factors (such as genetic tendency, head trauma, and substance abuse), psychological factors (such as maladaptive personality traits, difficult temperament, and physical/sexual abuse), and social factors (such as family conflict, loss of a loved one, bullying, and academic failure) [15].

Substance use among adolescents and young adults is a growing public health concern in developed countries such as the U.S. and Canada. Alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco are the substances most commonly used by adolescents and young adults. In Canada, the highest prevalence of alcohol (83%), cannabis (30%), and tobacco (18%) use was seen among young adults aged 20 to 24 years old followed by adolescents aged 15 to 19 years old (alcohol: 59%, cannabis: 21%, and tobacco: 10%) [16]. Similar trends in the prevalence of substance use were seen in the U.S. [17]. The magnitude of substance use among adolescents and young adults represents a major public health concern.

Substance use among adolescents and young adults is associated with many negative health, social, and economic consequences. These vary from suicidal behaviors [18] to low academic performance and school dropout [19], employment problems later in life [20], and risky behaviors [21]. Moreover, initiation of substance use in adolescence may be associated with the development of substance abuse and substance dependence later in life [22]. Risk factors associated with substance use are found at the individual (such as age, sex, personality and family history of substance use), interpersonal (such as relationship with parents, siblings, and peer pressure), and environmental (such as social norms, availability and accessibility of substance) levels [23].

Evidence suggests a complex interplay between substance use and vulnerability to mental health disorders [23,24]. Mental health disorders and substance use can co-occur due to a variety of reasons, including but not limited to: (1) common risk factors (such as environmental, genetic, personality, biological factors or traumatic events); (2) self-medication hypothesis (coping with psychological pressures and stressors as they relate to maturation, untreated traumas, and underlying conditions may lead to substance use and related risky behaviours); (3) substance use-induced mental health problems (individuals may develop a mental health problem as a direct (i.e., pharmacogenic) consequence of their substance use); and (4) substance use-related mental health problems (individuals may develop a mental health problem as an indirect (i.e., socio-economic stressors, unemployment, dysfunctional relationships) consequence of their substance use) [23,24].

Previous studies have been conducted examining the relationship between mental health disorders and substance use. Some studies have suggested that an association exists between depression and/or anxiety and alcohol, cannabis or tobacco use [25,26,27,28,29,30]. However, findings in the literature have been inconsistent [31,32,33,34,35,36]. Due to the high prevalence of mental health disorders and substance use among adolescents and young adults and the high potential of co-occurrence, further research in this important area is warranted. The purpose of this study was to examine the association and directionality between the three most common substances used (alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco) and two mental health disorders (depression and anxiety) among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. and Canada. Specifically, its objectives aimed to determine and quantify the association and directionality between: (1) depression and alcohol use, (2) depression and cannabis use, (3) depression and tobacco use, (4) anxiety and alcohol use, (5) anxiety and cannabis use, and (6) anxiety and tobacco use among adolescents and/or young adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources

We conducted an extensive systematic literature review on the following electronic databases: Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and PsycINFO. Our searches consisted of two major categories (substance use behaviors and mental health disorders) and their corresponding Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords: Subject OR Title (alcohol drinking or alcohol use or cannabis or marijuana smoking or marijuana use or smoking or tobacco smoking or tobacco use) AND Subject OR Title (depression or depressive disorders or major depressive disorder or anxiety or anxiety disorders or mood disorders). Snowball method (reference tracking) was also used to scan the reference lists of retrieved full-text articles and then to search manually for additional relevant literature.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria, Data Extraction and Analysis

The inclusion criteria for this review centered on the following: (1) English language peer-reviewed articles, available in full text, with human studies, published from 2000 to 2017. All study designs were eligible except for case series and case report. Newspaper, conference posters, dissertations were excluded; (2) depression/anxiety symptoms or disorders (major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, generalized anxiety disorder) data measured by using standardized scales, diagnostic criteria, self-reported surveys or diagnosed by healthcare professionals; (3) substance use (alcohol, cannabis, or tobacco) or disorder data presented, analyzed, and discussed; (4) target population that included adolescents and/or young adults; (5) only studies conducted in the US or Canada; and (6) data was either presented as an odds ratio (OR) or permitted the OR to be calculated.

Two screeners, independently, reviewed the list of identified articles to assess eligibility for inclusion in our study. Any disagreements were resolved by a tiebreaker vote. Extraction criteria included: year of publication, study design, sample size, target population, country where the study was conducted, measurement instrument used for substance use and mental health disorders, effect measure, covariates, and results. The effect measures examined the association between any of the following categories: (1) depression and alcohol use; (2) depression and cannabis use; (3) depression and tobacco use; (4) anxiety and alcohol use; (5) anxiety and cannabis use, and (6) anxiety and tobacco use. If a study discussed more than one of these categories, we extracted and analyzed all relevant effect measures separately.

2.3. Definitions of Mental Health Disorders and Substance Use

Overall, the definitions and measurements of mental health disorders and substance use in the various studies included in our review were heterogeneous. When multiple measures were used, we selected the most standardized and commonly used measure in order to maximize comparability between studies (Appendix A) [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60].

Standardized scales for depression or anxiety symptoms, instruments measuring depression or anxiety disorders using diagnostic criteria, and diagnosis of depression or anxiety by healthcare professionals were used by the various studies to define and select for mental health disorders. Certain studies examined subgroups of anxiety disorders such as social phobia or panic attack. We counted these subgroups as anxiety disorders and included them in our analysis. Similarly, a variety of well-established definitions and measurements were employed by a number of studies for substance use. For example, some studies defined participants as current users, whereas others as regular, daily, or ever users in their measurement categories (tobacco, alcohol and/or cannabis use). Appendix A provides the details for the definitions of mental health disorders and substance use employed by the various studies that were included in our analysis.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of both cross-sectional and longitudinal study designs. This scale includes three components and 8 items: (1) selection of study groups (4 items); (2) comparability of the groups (1 item); and the (3) ascertainment of the outcomes of interest (3 items) [61]. To assess the quality of the studies a star system was used. The quality of each study was determined by assigning it to one of three subgroups: (1) good (≥2 stars for selection of study groups, 1 star for comparability of the groups, and 3 stars for ascertainment of the outcomes of interest components); (2) fair (1 star for selection of study groups and 2 stars for ascertainment of the outcomes of interest components); or (3) poor (0 stars for selection of study groups, 0 stars for comparability of the groups, and ≤1 star for ascertainment of the outcomes of interest components). Risk of bias was designated as: low, if there was good quality in all components; unclear/moderate, if there was fair quality in one or more components without poor quality in any components; or high, if there was poor quality in any one of the components.

2.5. Meta-Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). For pooled mean effect size, random-effects models were used because differences were expected in the methodology and the samples of selected studies [62]. The primary outcome measure was odds ratio (OR). ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were either extracted from the articles or calculated by the authors using the quantitative data provided in the studies. Six separate meta-analyses were conducted. Q-statistics and I2 were used to examine the heterogeneity among studies. Publication bias was assessed by graphing funnel plots to visualize any possible asymmetries and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill test was conducted to adjust the results in case of publication bias [63]. Sensitivity analysis was done using one-study removed analysis. Moreover, subgroup analysis was performed using moderator variables including point estimate (crude or adjusted), target population (adolescents and young adults), severity of mental health disorders (symptoms and disorders), and intensity of substance use behavior (definitions).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

In total, 3656 articles (Medline (n = 945), PubMed (n = 883), Cochrane Library (n = 41), Embase (n = 1618), and PsycINFO (n = 169)) were identified by our initial search. After removing studies prior to the year 2000 and duplicates, 2341 articles remained. Title and abstract screening excluded 2177 articles, leaving 164 for full-text screening. After the full-text screening, 30 articles remained. Six additional articles were manually added by use of the snowball method.

In completing the title, abstract, and full-text screening, studies were excluded, if they were related to: (1) exposures other than those of interest in this study, such as cessation/withdrawal from substances, use of e-cigarettes, opiates, cocaine, methamphetamine, sedative, and hallucinogens; (2) outcomes other than those of interest in this study, such as suicide ideations, bipolar disorder, mania, postpartum depression, and hypomania; (3) the recruited population was other than that of interest in this study, such as adults, participants who were pregnant, specific ethnic groups or gender, military veterans, participants with comorbid chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes, cardiovascular or lung diseases.

All 36 selected articles used either a cross-sectional (n = 19) or longitudinal (n = 17) study design. The summary of our study selection is shown in a PRISMA diagram (Figure 1). Study characteristics are presented in Table 1. The quality of studies was assessed using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS), which found 5 studies with a low, 27 with a moderate, and 4 with a high risk of bias.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics and associations of selected studies.

| First Author’s Name, Year, Country | Sample Size | Target Population | Substance Use Measure | Mental Health Disorders Assessment | % of Depressive Participants | Controlled Variables | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association between Depression and Alcohol Use | |||||||

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||

| Elissa Weitzman, 2004, U.S. [55] | 27,687 | College students aged 18–24 | Binge/non-drinkers | Depressive symptoms: The 5-item subscale of SF36 | 4.9% | Age, sex, ethnicity | Adjusted: 1.05 (0.96–1.14) |

| Martha Kubik, 2005, U.S. [33] | 3466 | Grade 7 students | Heavy/non-drinkers | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16. | 35% | Age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), smoking, cannabis, and inhalants use | Adjusted: 2.03 (1.30–3.17) |

| Susan Roberts, 2009, U.S. [32] | 418 | College students | Binge/non-drinkers | Depressive symptoms: BDI-II, cut-off point of 20 | 22% | - | Crude: 0.99 (0.61–1.58) |

| Elisabeth Simantov, 2000, U.S. [48] | 5513 | Grade 7–12 students | Regular/non-drinkers | Depressive symptoms: Modified version of CDI, cut-off point of 9 | 18.2% | - | Crude: 2.08 (1.79–2.42) |

| Linda Richter, 2015, U.S. [26] | 24,445 | Adolescents aged 12–20 | Binge/non-drinkers | Major depressive disorder: Diagnosed depression (self-reported) | - | Sex, ethnicity, and age | Adjusted: 1.45 (1.11–1.91) |

| Eleanor Hanna, 2001, U.S. [31] |

2001 | Adolescents aged 12–16 | Moderate/non-drinkers | Major depressive disorder: Diagnostic interview schedule, DSM-III | 9% | Age, sex, ethnicity, family poverty level, school problem, smoking status | Adjusted: 3.31 (1.39–7.90) |

| Longitudinal Studies: Alcohol Use (Exposure) → Depression (Outcome) | |||||||

| Mallie Paschall, 2005, U.S. [44] | 13,892 | Grade 6–12 students | Moderate/non-drinkers | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16. | 5.3% | - | Crude: 1.17 (1.11–1.23) |

| David Brook, 2002, U.S. [52] | 736 | Adolescents aged 14, 13-year follow-up | Ever/never alcohol users | Major depressive disorder: Modified version of CIDI | 8.3% | Age, sex, parental educational level, family income, prior psychiatric disorders | Adjusted: 1.72 (1.35–2.20) |

| Longitudinal Study: Depression (Exposure) → Alcohol Use (Outcome) | |||||||

| Kiyuri Naicker, 2012, Canada [51] | 1027 | Adolescents aged 16–17, 10-year follow-up | Heavy/non-drinkers | Major Depressive Disorder: CIDI-SF, cut-off point of 5 | 6.9% | Sex and SES | Adjusted: 1.78 (1.10–2.88) |

| Association between Depression and Cannabis Use | |||||||

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||

| Lee Ridner, 2005, U.S. [40] | 895 | College students aged 18–24 | Current/non- cannabis users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16 | - | - | Crude: 1.27 (1.00–1.61) |

| Susan Roberts, 2009, U.S. [32] | 418 | College students | Current/non- cannabis users | Depressive symptoms: BDI-II, cut-off point of 20 | 22% | - | Crude: 1.99 (1.23–3.22) |

| Martha Kubik, 2005, U.S. [33] | 3466 | Grade 7 students | Current/non- cannabis users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16 | 35% | Age, ethnicity, SES, smoking, alcohol, and inhalants use. | Adjusted: 1.02 (0.66–1.57) |

| Longitudinal Studies: Cannabis Use (Exposure) → Depression (Outcome) | |||||||

| Daniel Rasic, 2012, Canada [27] | 976 | Grade 10 students, 2-year follow-up | Current/non- cannabis users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 22 (M) and 24 (F) | 20% | Sex | Adjusted: 1.24 (1.05–1.46) |

| Katholiki Georgiades, 2007, Canada [50] | 1282 | Adolescents aged 12–16, 14-year follow-up | Past 6-month/non- cannabis users | Major depressive disorder: CIDI-SF | 11.8% | Physical health, life satisfaction, personal income, years of education | Adjusted: 1.97 (0.81–4.81) |

| David Brook, 2002, U.S. [52] | 736 | Adolescents aged 14, 10-year follow-up | Ever/never cannabis users | Major depressive disorder: Modified version of CIDI | 8.3% | Age, sex, parental educational level, family income, prior psychiatric disorders | Adjusted: 1.36 (1.14–1.62) |

| Naomi Marmorstein, 2011, U.S. [56] | 1252 | Adolescents aged 17, A 6-year follow-up |

CUD/non- cannabis users | Major depressive disorder: The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R. | 13.9% | MDD by age 17 and gender | Adjusted: 1.86 (1.11–3.11), |

| Valerie Harder, 2008, U.S. [53] | 1494 | Adolescents aged 12–16, 7-year follow-up | CUD/non- cannabis users | Major depressive disorder: CIDI, DSM IV diagnostic criteria | 6% | Ethnicity, family income, free lunch, tobacco, alcohol, and other illegal drug use, parental monitoring, concentration, behavior problems, shyness, anxiety symptoms, intervention status | Adjusted: 1.33 (0.70–2.53) |

| Longitudinal Study: Depression (Exposure) → Cannabis Use (Outcome) | |||||||

| Cynthia Suerken, 2014, U.S. [45] | 3146 | College students, A 6-month follow-up |

Ever/never cannabis users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, Iowa short form | - | Sex, ethnicity, parental education and spending money available, varsity athlete, club, intramural sports, member of a sorority/fraternity, attend religious services, live on campus, relationship status, current use of tobacco, alcohol, and lifetime use of other illicit drugs | Crude: 1.03 (1.01–1.05) |

| Association between Depression and Tobacco Use | |||||||

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||

| Lee Ridner, 2005, U.S. [40] | 895 | College students aged 18–24 | Current/non-tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16 | - | - | Crude: 1.49 (1.18–1.90) |

| Susan Roberts, 2009, U.S. [32] | 418 | College students, aged 18–21 | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: BDI-II, cut-off point of 20 | 22% | - | Crude: 2.08 (1.29–3.36) |

| Elisabeth Simantov, 2000, U.S. [48] | 5513 | Grade 7–12 students | Regular/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: Modified version of CDI, cut-off point of 9 | 18.2% | - | Crude: 2.47 (2.06–2.97) |

| Sung Chung, 2014, U.S. [25] | 11,848 | Grade 9–11 students | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: 1 item question |

28.4% | - | Crude: 1.33 (1.16–1.53) |

| Shahm Martini, 2002, U.S. [46] | 11,201 | Adolescents aged 12–17 | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: YSR, cut-off point of 3 | - | Age, ethnicity, school attendance, site, substance use behaviors | Crude: 1.83 (1.67–2.01) |

| Carla Berg, 2008, U.S. [47] | 299 | Adolescents aged 10–19 | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: A 5-item question, cut-off point of 21 |

12% | Age, sex, ethnicity, church attendance, perceived parental attitude | Crude: 3.83 (1.65–8.88) |

| Martha Kubik, 2005, U.S. [33] | 3466 | Grade 7 students | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16 | 35% | Age, ethnicity, SES, all other substance use behaviors | Adjusted: 1.56 (1.14–2.14) |

| Gilat Grunau, 2009, Canada [28] | 6943 | Students aged 13–18 | Current/non- tobacco users | Major depressive disorder: Prescribed depression medications | 2.2% | Age, sex, ethnicity, parent(s), sibling(s), peer(s) smokes, anxiety | Adjusted: 2.59 (1.79–3.73) |

| Amanda Richardson, 2012, U.S. [49] | 1884 | Adolescents aged 12–15 | Ever/never tobacco users | Major depressive disorder: NIMH-DISC-IV | - | Age, ethnicity, attending school, poverty index ratio, live with smokers, anxiety disorders | Adjusted: 2.80 (1.13–6.91) |

| Eleanor Hanna, 2001, U.S. [31] | 719 | Adolescents aged 12–16 | Current/non- tobacco users | Major depressive disorder: Diagnostic interview schedule, DSM-III | 9% | Age, sex, ethnicity, family poverty status, school problem, drinking status | Adjusted: 0.98 (0.33–2.90) |

| Longitudinal Studies: Tobacco Use (Exposure) → Depression (Outcome) | |||||||

| Brian Duncan, 2005, U.S. [41] | 13,068 | Students grade 7–12, 1-year follow-up | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 22 (M) and 24 (F) | - | Disability, age, ethnicity, household, parental education, county-level variables | Crude: 2.37 (2.02–2.77) |

| Elizabeth Goodman, 2000, U.S. [42] | 8704 | Adolescents aged 11–22, 1-year follow-up | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 22 (M) and 24 (F) | 6.4% | Age, sex, ethnicity, parental education | Crude: 2.31 (1.83–2.92) |

| Katholiki Georgiades, 2007, Canada [50] | 1282 | Adolescents aged 12–16, 14-year follow-up | Daily/non- tobacco users | Major depressive disorder: CIDI-SF | 11.8% | Physical health, life satisfaction, personal income, years of education | Adjusted: 1.93 (1.01–3.70) |

| David Brook, 2002, U.S. [52] | 736 | Adolescents aged 14, A 13-year follow-up |

Ever/never tobacco users | Major depressive disorder: Modified version of CIDI | 8.3% | Age, sex, parental educational level, family income, prior psychiatric disorders | Adjusted: 1.18 (1.01–1.39) |

| Longitudinal Studies: Depression (Exposure) → Tobacco Use (Outcome) | |||||||

| Elizabeth Goodman, 2000, U.S. [42] | 6947 | Adolescents aged 11–22, 1-year follow-up | Current/non- tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 22 (M) and 24 (F) | 6.4% | Age, sex, ethnicity, education | Crude: 2.81 (1.67–4.74) |

| Kiyuri Naicker, 2012, Canada [51] | 681 | Adolescents aged 16–17, 10-year follow-up | Daily/non- tobacco users | Major depressive disorder: CIDI-SF, cut-off point of 5 | 6.9% | Sex and SES | Adjusted: 2.89 (1.53–5.45) |

| Jie Wu Weiss, 2004, U.S. [37] | 1699 | Grade 6 students, A 1-year follow-up |

Ever/never tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16 | - | change in depression and hostility, sex, ethnicity, SES | Adjusted: 1.76 (1.30–2.38) |

| Jennifer Mendel, 2012, U.S. [38] | 1205 | Grade 10–11 students, A 5-year follow-up |

Ever/never tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 16 | - | Sex, parental marital status, family income, education level, marital status, children, GPA, delinquency, stressful life events, family support, quality of friendship, parental smoking, adolescent alcohol, cannabis use, extent of alcohol problems, peers who drink or use drugs, change in CESD and alcohol use | Adjusted: 0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

| Jennifer O’Loughlin, 2016, Canada [54] | 690 | Grade 5 students, 7-year follow-up |

Ever/never tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: 6-item question | - | Age, sex, mother’s education | Adjusted: 1.34 (1.16–1.56) |

| Marcus Munafo, 2007, U.S. [39] | 12,149 | Grade 7–12 students, 1-year follow-up | Ever/never tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 22 (M) and 24 (F) | - | Age, sex, ethnicity, depressed mood, parental/peer tobacco, alcohol use, delinquency score | Adjusted: 1.13 (1.03–1.25) |

| William Lechner, 2016, U.S. [43] | 2460 | Grade 9 students, A 1-year follow-up |

Ever/never tobacco users | Depressive symptoms: CES-D, cut-off point of 22 (M) and 24 (F) | - | Age, sex, ethnicity, school, living situation, parental education, use of alcohol and other tobacco products | Adjusted: 1.02 (1.01–1.04) |

| First author’s name, year, country | Sample size | Target population | Substance use measure | Mental health disorders assessment | % of participants with anxiety | Controlled variables | OR (95% CI) |

| Association between Anxiety and Alcohol Use | |||||||

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||

| Margo Villarosa, 2014, U.S. [29] | 532 | College students aged 18–22 | Alcohol Use Disorder: AUDIT | Social anxiety symptoms: SIAS | - | - | Crude: 1.61 (1.29–2.00) |

| Meade Eggleston, 2003, U.S. [57] | 284 | College students aged 17–23 | Binge/non-drinkers | Social anxiety symptoms: SIAS | - | - | Crude: 1.55 (1.15–2.10) |

| Esther Strahan, 2010, U.S. [58] | 697 | College students aged 17–27 | Alcohol Use Disorder: AUDIT | Social anxiety symptoms: SIAS | - | - | Crude: 1.04 (1.01–1.08) |

| Ping Wu, 2009, U.S. [59] | 781 | Adolescents aged 13–17 | Frequent, heavy/non-drinkers | Any anxiety disorders: DISC | 18.4% | Age, ethnicity, public assistance, not living with parents, parental drug/alcohol problems, site | Adjusted: 1.74 (1.07–2.81) |

| Linda Richter, 2015, U.S. [26] | 24,445 | Adolescents aged 12–20 | Binge/non-drinkers | Any anxiety disorders: Diagnosed anxiety (self-reported) | - | Age, sex, ethnicity | Adjusted: 1.54 (1.12–2.12) |

| Robert Roberts, 2007, U.S. [35] | 4175 | Adolescents aged 11–17 | Alcohol Use Disorder: AUD | Any anxiety disorders: DISC-IV | 6.9% | Mood, conduct oppositional, and ADHD disorders. | Crude: 1.57 (0.72–3.40) |

| Nancy Low, 2008, U.S. [36] | 632 | Adolescents aged 13–19 | Alcohol Use Disorder: AUD | Any Anxiety Disorders: PRIME-MD | 7% | Age, sex, ethnicity, sample site, mood disorders | Adjusted: 3.80 (1.21–11.91) |

| Longitudinal Study: Anxiety (Exposure) → Alcohol Use (Outcome) | |||||||

| Julia Buckner, 2008, U.S. [60] | 816 | Students aged 15–17, 14-year follow-up | Alcohol Use Disorder: AUD | Any anxiety disorders: K-SADS | - | Sex, conduct, mood, CUDs, T1 AUD excluded | Adjusted: 2.16 (0.82–5.69) |

| Association between Anxiety and Cannabis Use | |||||||

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||

| Julia Buckner, 2008, U.S. [30] | 337 | College students aged 18–26 | Frequent/non-cannabis users | Social anxiety symptoms: SIAS | 18.8% | - | Crude: 1.23 (0.88–1.73) |

| Robert Roberts, 2007, U.S. [35] | 4175 | Adolescents aged 11–17 | Cannabis Use Disorder: CUD | Any anxiety disorder: DISC-IV | 6.9% | Mood, conduct oppositional, and ADHD disorders | Crude: 1.38 (0.70–2.75) |

| Nancy Low, 2008, U.S. [36] | 632 | Adolescents aged 13–19 | Cannabis Use Disorder: CUD | Any anxiety disorder: PRIME-MD | 7% | Age, sex, ethnicity, sample site, mood disorders | Crude: 1.40 (0.40–4.70) |

| Longitudinal Study: Anxiety (Exposure) → Cannabis Use (Outcome) | |||||||

| Julia Buckner, 2008, U.S. [60] | 816 | Students aged 15–17, 14-year follow-up | Cannabis Use Disorder: CUD | Social anxiety disorder: K-SADS | - | Sex, conduct, mood, AUDs, T1 CUD excluded | Adjusted: 3.28 (1.14–9.40) |

| Association between Anxiety and Cannabis Use | |||||||

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||

| Gilat Grunau, 2009, Canada [28] | 6943 | Students aged 13–18 | Current/non-cannabis users | Any anxiety disorder: Prescribed anxiety medications | 0.6% | Sex, ethnicity, age, parent(s), sibling(s), peer(s) smokes, depression | Adjusted: 1.83 (1.05–3.22) |

| Ping Wu, 2009, U.S. [59] | 781 | Adolescents aged 13–17 | Daily/non- cannabis users | Any anxiety disorders: DISC | 18.4% | Age, ethnicity, public assistance, not living with parents, parental drug/alcohol problems, site. | Adjusted: 3.14 (1.69–5.81) |

| Amanda Richardson, 2012, U.S. [49] | 1884 | Adolescents aged 12–15 | Ever/never cannabis users | Any anxiety disorder: NIMH-DISC-IV |

- | Age, ethnicity, attending school, poverty index ratio, live with smokers, depressive disorder | Adjusted: 4.70 (1.61–13.75) |

| Longitudinal Study: Tobacco Use (Exposure) → Anxiety (Outcome) | |||||||

| Renee Goodwin, 2005, U.S. [34] | 940 | Students aged 14–18, anxiety: young adults mean age 24.2 | Ever/never cannabis users | Any anxiety disorders: K-SADS |

- | - | Crude: 1.88 (1.47–2.41) |

| Longitudinal Study: Anxiety (Exposure) → Tobacco Use (Outcome) | |||||||

| Renee Goodwin, 2005, U.S. [34] | 940 | Students aged 14–18, tobacco use: young adults mean age 24.2 | Ever/Never cannabis users | Any anxiety disorders: K-SADS |

- | - | Crude: 1.38 (0.83–2.29) |

All terms/acronyms used in Table 1 are fully defined in Appendix A.

3.2. Synthesis of Results

The results of the meta-analysis found significant positive associations between depression and alcohol use (OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.24–1.83), cannabis use (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.10–1.51) and tobacco use (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.43–1.92). Similarly, significant positive associations were found between anxiety and alcohol use (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.19–2.00), cannabis use (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.02–1.81) and tobacco use (OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.54–3.17) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall pooled estimates for mental health disorders and substance use.

| Topics | Study Designs | n | OR (95% CI) | I2% and p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression and Alcohol use | Overall | 9 | 1.50 (1.24–1.83) | 90.54, <0.001 |

| Cross-Sectional | 6 | 1.57 (1.09–2.26) | 92.89, <0.001 | |

| Longitudinal: Alcohol use at baseline | 2 | 1.39 (0.95–2.03) | 89.24, <0.001 | |

| Longitudinal: Depression at baseline | 1 | 1.78 (1.10–2.88) | n/a | |

| Depression and Cannabis use | Overall | 9 | 1.29 (1.10–1.51) | 74.79, <0.01 |

| Cross-Sectional | 3 | 1.34 (0.97–1.84) | 53.26, 0.12 | |

| Longitudinal: Cannabis use at baseline | 5 | 1.33 (1.19–1.49) | 0.00, 0.53 | |

| Longitudinal: Depression at baseline | 1 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | n/a | |

| Depression and Tobacco use | Overall | 20 | 1.65 (1.43–1.92) | 96.23, <0.01 |

| Cross-Sectional | 10 | 1.87 (1.55–2.25) | 78.60, <0.01 | |

| Longitudinal: Tobacco use at baseline | 4 | 1.87 (1.23–2.85) | 92.95, <0.01 | |

| Longitudinal: Depression at baseline | 7 | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) | 89.56, <0.001 | |

| Anxiety and Alcohol use | Overall | 8 | 1.54 (1.19–2.00) | 81.52, <0.001 |

| Cross-Sectional | 7 | 1.51 (1.16–1.97) | 83.28, <0.001 | |

| Longitudinal: Alcohol use at baseline | - | - | - | |

| Longitudinal: Anxiety at baseline | 1 | 2.16 (0.82–5.69) | n/a | |

| Anxiety and Cannabis use | Overall | 4 | 1.36 (1.02–1.81) | 0.39, 0.39 |

| Cross-Sectional | 3 | 1.27 (0.94–1.70) | 0.00, 0.94 | |

| Longitudinal: Cannabis use at baseline | - | - | - | |

| Longitudinal: Anxiety at baseline | 1 | 3.28 (1.14–9.40) | n/a | |

| Anxiety and Tobacco use | Overall | 4 | 2.21 (1.54–3.17) | 46.17, 0.13 |

| Cross-Sectional | 3 | 2.67 (1.62–4.37) | 33.12, 0.22 | |

| Longitudinal: Tobacco use at baseline | 1 | 1.88 (1.47–2.41) | n/a | |

| Longitudinal: Anxiety at baseline | 1 | 1.38 (0.83–2.29) | n/a |

3.3. Analysis of the Directionality

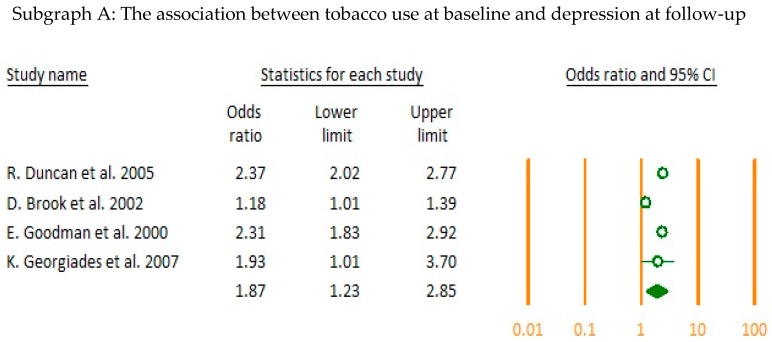

The directionality of the association between each relevant category was assessed by pooled analysis of the longitudinal studies. Results showed that there was a significant positive bi-directional association between tobacco use at baseline leading to depression at follow-up (OR = 1.87, CI = 1.23–2.85) and depression at baseline leading to tobacco use at follow-up (OR = 1.22, CI = 1.09–1.37). Cannabis use at baseline was significantly associated with depression at follow-up (OR = 1.33, CI = 1.19–1.49) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Examining the directionality in longitudinal studies (forest plots A–C).

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity detected upon pooled analysis, subgroup analysis was conducted to examine whether the differences within categories could be attributed to specific moderators (age group, measures of mental health disorder, and severity of substance use). Results of our subgroup analysis are summarized in Table 3. Results from the subgroup analysis by age group including adolescents (aged 10 to 18 years old) and young adults (aged 18 to 24 years old) found that the association between mental health disorders and substance use remained significant among adolescents but not among young adults. Subgroup analysis based on severity of mental health disorders showed a consistently higher point estimate for clinically diagnosed mental health disorder patients. Finally, subgroup analysis based on the intensity of substance use showed a recurring theme, whereby, as severity increased, mental health disorders also increased (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis for mental health disorders and substance use.

| Subgroup Analysis | n | OR (95% CI) | I2% and p-Value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression and Alcohol use | Point Estimate | Crude | 3 | 1.37 (0.87–2.18) | 96.08, <0.001 | 0.56 |

| Adjusted | 6 | 1.62 (1.19–2.19) | 84.60, <0.001 | |||

| Target Population | Adolescents | 7 | 1.69 (1.28–2.25) | 90.63, <0.001 | 0.28 | |

| Young adults | 3 | 1.28 (0.83–1.97) | 82.52, <0.001 | |||

| Severity of MHDs 1 | Symptoms | 5 | 1.37 (1.08–1.75) | 94.04, <0.001 | 0.21 | |

| Disorders | 4 | 1.67 (1.38–2.02) | 14.68, 0.32 | |||

| Intensity of substance use | Not binge drinkers | 6 | 1.61 (1.29–2.01) | 79.79, <0.001 | 0.06 | |

| Binge drinkers | 6 | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 87.67, <0.001 | |||

| Depression and Cannabis use | Point Estimate | Crude | 3 | 1.27 (0.95–1.69) | 80.29, <0.001 | 0.85 |

| Adjusted | 6 | 1.31 (1.17–1.46) | 0.00, 0.48 | |||

| Target Population | Adolescents | 6 | 1.34 (1.17–1.54) | 9.96, 0.35 | 0.46 | |

| Young adults | 4 | 1.22 (0.99–1.51) | 72,62, 0.01 | |||

| Severity of MHDs | Symptoms | 5 | 1.20 (1.01–1.42) | 73.16, <0.001 | 0.16 | |

| Disorders | 4 | 1.41 (1.21–1.65) | 0.00, 0.60 | |||

| Intensity of substance use | Cannabis use | 7 | 1.25 (1.06–1.47) | 77.10, <0.001 | 0.23 | |

| CUD 2 | 2 | 1.63 (1.09–2.44) | 0.00, 0.42 | |||

| Depression and Tobacco use | Point Estimate | Crude | 8 | 1.99 (1.65–2.40) | 86.62, <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted | 12 | 1.30 (1.16–1.45) | 87.12, <0.001 | |||

| Target Population | Adolescents | 18 | 1.67 (1.43–1.96) | 96.56, <0.001 | 0.40 | |

| Young adults | 3 | 1.37 (0.89–2.12) | 84.18, <0.001 | |||

| Severity of MHDs | Symptoms | 14 | 1.61 (1.36–1.89) | 97.18, <0.001 | 0.48 | |

| Disorders | 6 | 1.91 (1.22–2.97) | 78.86, <0.001 | |||

| Intensity of substance use | Ever smokers | 7 | 1.14 (1.04–1.25) | 84.89, <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Current smokers | 14 | 1.90 (1.62–2.23) | 82.65, <0.001 | |||

| Anxiety and Alcohol use | Point Estimate | Crude | 4 | 1.37 (1.00–1.88) | 86.27, <0.001 | 0.3 |

| Adjusted | 4 | 1.70 (1.32–2.18) | 0.00, 0.47 | |||

| Target Population | Adolescents | 5 | 1.69 (1.33–2.14) | 0.00, 0.64 | 0.29 | |

| Young adults | 3 | 1.35 (0.96–1.90) | 90.40, <0.001 | |||

| Severity of MHDs | Symptoms | 3 | 1.35 (0.96–1.90) | 90.40, <0.001 | 0.29 | |

| Disorders | 5 | 1.69 (1.33–2.14) | 0.00, 0.64 | |||

| Intensity of substance use | Alcohol use | 6 | 1.49 (1.26–1.76) | 0.00, 0.88 | 0.59 | |

| AUD 3 | 5 | 1.71 (1.05–2.79) | 83.88, <0.001 | |||

| Anxiety and Cannabis use | Point Estimate | Crude | 2 | 1.26 (0.93–1.71) | 0.00, 0.76 | 0.19 |

| Adjusted | 2 | 2.28 (1.00–5.20) | 5.37, 0.30 | |||

| Target Population | Adolescents | 3 | 1.71 (1.02–2.89) | 0.00, 0.38 | 0.29 | |

| Young adults | 1 | 1.23 (0.88–1.73) | n/a | |||

| Severity of MHDs | n/a | |||||

| Intensity of substance use | Cannabis use | 1 | 1.23 (0.88–1.73) | n/a | 0.29 | |

| CUD | 3 | 1.71 (1.02–2.89) | 0.00, 0.38 | |||

| Anxiety and Tobacco use | Point Estimate | Crude | 1 | 1.78 (1.42–2.22) | n/a | 0.14 |

| Adjusted | 3 | 2.67 (1.62–4.37) | 33.125, 0.22 | |||

| Target Population | n/a | |||||

| Severity of MHDs | n/a | |||||

| Intensity of substance use | Ever | 3 | 1.62 (0.67–3.92) | 69.87, 0.04 | 0.58 | |

| Current | 4 | 2.10 (1.69–2.62) | 0.00, 0.52 | |||

1 Mental Health Disorders, 2 Cannabis Use Disorder, 3 Alcohol Use Disorder.

3.5. Publication Bias

Funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias in the included studies that examined the association between depression and alcohol use; depression and cannabis use; depression and tobacco use; anxiety and alcohol use; and anxiety and tobacco use. However, there was evidence of publication bias in the included studies which examined the association between anxiety and cannabis use. Therefore, in these instances, a Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method was used to test and adjust for the publication bias in our meta-analysis.

4. Discussion

Our findings suggest that a significant association exists between depression and the use of alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco. Similarly, significant associations were found to exist between anxiety and the use of alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco. A bidirectional relationship was observed between depression and the use of tobacco. Additionally, we found evidence that cannabis use at baseline led to depression at follow-up. The results of our study were consistent with those reported in previous systematic reviews [64,65,66] and provide additional evidence in support of the inter-association between mental health disorders and substance use.

Harmful alcohol use, which has been defined as heavy episodic or binge drinking, is an important health issue among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. [67]. The adolescent/young adult brain is still developing, and there is evidence to suggest that frequent use of alcohol at this age may lead to mental health disorders including depression [68,69]. Our results support these findings. We found that alcohol use was a significant predictor of higher levels of depression among adolescents and young adults. However, further research is needed in this area with more longitudinal studies, using longer follow-up periods.

A systematic review conducted by Lev-Ran et al. found a positive association between cannabis use at baseline and the development of depression [70]. Our results corroborate these findings and demonstrate that the overall pooled estimate for depression among heavy cannabis users was higher, compared to light users. Another systematic review by Number-Kedzior et al. found a significant positive association between cannabis use at baseline and anxiety at follow-up [66]. In our study, it was not possible to infer whether such a causal relationship exists due to the lack of sufficient studies on this topic, which fit our inclusion criteria. Proposed mechanisms for the association between cannabis and depression could be due to biological effects from the alteration in neurotransmitters such as serotonin in the brain [71] and its impact on developing depression and mediating psychosocial factors such as unemployment and educational failure [50]. We observed that when adjusting for personal income and years of education, the association between cannabis use and depression was reduced [50].

In our study, we found a stronger pooled estimate for tobacco use predicting depression, compared to depression predicting tobacco use. Moreover, a stronger pooled estimate was observed in those studies that used a clinical measure of depression rather than depressive symptoms. Although, our study was limited in investigating the associations rather than the causality between mental health disorders and substance use, our results are biologically plausible. For instance, the association between tobacco use and anxiety or depression may be due to the effect of nicotine on the central neurotransmitter systems and peripheral circulating stress hormones [72]. In the brain, the primary target of nicotine (the addictive substance found in tobacco) is the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nACHRs). The nACHRs have a large number of subtypes responsible for the regulation of different neurotransmitter systems. Nicotine can make alterations in the balance of these neurotransmitter systems by activating or inactivating the receptors responsible for release of stimulatory (glutamate), inhibitory (GABA), and modulatory (dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin) neurotransmitters in different brain regions. Thus, different behavioral outputs such as depression or anxiety may occur [72]. The ability of nicotine to act as an anxiolytic or anxiogenic and depressant or anti-depressant agent is complex and may dependent on the severity and duration of its use, the route of administration, and the genetic and behavioral state of the individual user [72].

The effects of nicotine on the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis are centrally mediated by the stimulation of neurotransmitter systems [73]. Acute nicotine exposure can result in increase in basal level of stress hormones by stimulating the HPA axis [73]. The anxiogenic effect of nicotine may be explained by the acute peripheral effect of tobacco smoking such as the increases observed in blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol output. Also, nicotine increases corticosteroids in the amygdala, a brain area critical for emotionality. With chronic use of tobacco, nicotine alters activity of the HPA axis. The HPA axis in combination with genetic factors may be involved in producing tolerance to the effects of nicotine. Thus, this might predispose smokers to depressive episodes during withdrawal [72,74].

The association between anxiety and tobacco use might be explained by the negative effect of tobacco use on different brain pathways such as neurotransmitter systems, inflammation and the immune system, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways, neurotrophins and neurogenesis regulations, mitochondrial function, and epigenetic influences. Alteration in abovementioned pathways can also play a role in development of anxiety disorders [75].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. There is a high level of congruence between our findings and those reported in the existing literature. However, this systematic review is unique because: (1) it incorporates only studies originating in the U.S. and Canada, (2) it focuses on the adolescent and young adult population, and (3) it examines the associations and directionality between depression or anxiety and alcohol, cannabis, or tobacco use, separately.

Our study also has some limitations. We found that certain factors such as the study design (longitudinal vs. cross-sectional), the intensity of substance use (light vs. heavy), and the variation in clinical diagnosis (depressive and anxiety disorders vs. symptoms) affect the outcomes of our study. Participant’s age (adolescents vs. young adults) also influenced the inter-association between substance use behaviors and mental health disorders. In our review, several of our included studies used different instruments to measure depression and anxiety and a broad spectrum of measurements for substance use, making the results difficult to compare due to their heterogeneity. When extracting data, we were unable to calculate the unadjusted odds ratio from all included studies. Different studies varied in the degree to which they controlled for potential confounders. Variation in the population sampled, length of follow-up in longitudinal studies, and different sample sizes also added to the variability.

4.2. Implications for Practice, Research and Policy

The co-occurrence of mental health disorders and/or substance use presents complex challenges in their prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. If left untreated, these conditions may result in loss of productivity, poor educational outcomes, increased psychiatric hospitalizations/emergency department visits, inefficient use of limited healthcare resources, and a higher prevalence of chronic diseases. By affecting change at the personal (increase awareness), interpersonal (decrease stigma), and societal (policies and interventions) levels, we can assist adolescents and young adults to make better choices, seek support as needed, and live healthier and well-adjusted lives.

Overall, our systematic review and meta-analysis found a clear association between depression/anxiety and substance use, regardless of the severity of the mental health disorder or the intensity of substance use. These findings have significant implications and may impact:

-

(1)

Practice: our study helps highlight the importance of addressing adolescents and young adults’ mental health (depression/anxiety) and substance use behaviors (drinking, smoking, cannabis use) early, concurrently and with an integrated clinical approach through the use of timely screening, team-based diagnosis, patient-oriented treatment and effective interventions. These observations underscore the need for a shift in our collective perspective, when implementing integrated services for patients with co-occurring disorders.

-

(2)

Research: our findings corroborate and expand those reported in previous studies and provide invaluable insight and guidance to future rigorous, longitudinal research that aims to widen our knowledge of psychopathology by elucidating the associated links and delineating best practices in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of co-occurring mental health disorders and substance use. Additionally, it will be of keen scientific interest to investigate and determine whether substance use cessation treatments lead to reduction and/or remission of depression/anxiety or whether the treatment of depression/anxiety leads to reduction and/or cessation of substance use among adolescents and young adults.

-

(3)

Policy: our results demonstrate that integrated treatment approaches and health education campaigns are needed to improve quality of care and increase awareness among the public and healthcare practitioners of the associations between depression/anxiety and substance use among adolescents and young adults. School-based intervention programs, in particular, hold much promise as they could encourage adolescents and young adults to seek professional help safely and in a supportive environment.

4.3. Recommendations

Given the findings of our study, it is important that patients diagnosed with mental health disorder and/or a substance use problems be evaluated, screened, and if need be, treated for both conditions. To assist in this regard, the following recommendations are proposed:

-

(1)

Bilateral cooperation between the U.S. and Canada: along with sharing the longest international boarder, the two countries share many common socio-cultural factors, demonstrate similar patterns in the prevalence of mental health disorders and substance use, and report common health priorities (i.e., advancement of mental health and substance use services) [76,77]. Therefore, it would be beneficial for key stakeholders at educational settings in both the U.S. and Canada to collaborate and exchange information and ideas on how to further improve their health education and promotion programs.

-

(2)

Implementation of the quadrants of care model (the New York Model): in our systematic review, it became apparent that as the severity of mental health disorders and intensity of substance use varied, different approaches to their healthcare management were needed. Thus, the potential usefulness of the quadrants of care model to most appropriately direct the efforts of healthcare professionals [78]. Individuals treated simultaneously by two or more healthcare providers at one point of entry may receive an integrated treatment plan for both conditions. By following this model, individuals will receive an appropriate level of care based on their needs, and this will ensure the efficient use of available resources.

-

(3)

Reforming the healthcare system: healthcare reforms are needed to make the necessary changes from the current parallel and independent practice sectors towards coordinated systems of care. Coordinated practice sectors will require sharing funds, developing mandates in concert, and treating affected individuals collaboratively. Reforms should be broad and encompass all levels of service delivery including health promotion and prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and research.

-

(4)

Efficient use of limited resources: preventive interventions, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of the co-occurrence of mental health disorders and substance use, can improve the quality of life of adolescents and young adults. Addressing this issue upstream will reduce the associated healthcare costs and permit the efficient use of limited resources, including the need for frequent psychiatric hospitalizations, over-use of emergency departments, and ambulatory care.

-

(5)

Training of healthcare providers: it is essential to cross-train healthcare providers from different sectors to increase their awareness of the existing association between mental health disorders and substance use. There is a need for the characterization of patient risk profiles, the use of valid assessment tools, and updated diagnostic and treatment guidelines to help improve outcomes for these two conditions among adolescents and young adults.

5. Conclusions

This study offers significant insight into the association and directionality between substance use (alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco) and mental health disorders (depression and anxiety) among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. and Canada. Our findings can help guide key stakeholders (school administrators, nurses, physicians, public health professionals, and policymakers) in making evidence-based recommendations for school-based interventions, policy, and programming. It is increasingly evident that adolescents and young adults with substance use issues may also suffer from co-occurring mental health disorders. However, they are frequently undiagnosed and, consequently, they do not receive the specialized cross-treatment needed to address both conditions. To be most effective, school-based substance use and mental health programmes should consider integrating and expanding their services for patients with dual disorders. Further research is needed to help guide evidence-based treatment and initiatives for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Rita Hanoski, Health Education and Promotion Coordinator and Jocelyn Orb, Manager, Student Health Services, University of Saskatchewan.

Appendix A. Definitions of Mental Health Disorders and Substance Use

| Depression |

| The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) [27,33,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II) [32] |

| One item question: Whether respondents felt so sad or hopeless almost daily for two consecutive weeks that usual activities were interrupted [25] |

| Youth self-report checklist (8 self-reported symptoms of depression within the past 6 months): I feel guilty, I cry a lot, I deliberately try to hurt myself, I think of killing myself, I feel lonely, I am unhappy, I feel that no one loves me, and I feel worthless (YSR) [46] |

| A five-item question: within the past 12 months how often have you felt too tired to do things? Felt unhappy, sad, or depressed? Felt hopeless about the future? Felt nervous or tense? And worried too much about things? [47] |

| Modified version of the children depression inventory (CDI) [48] |

| Depression medication prescribed by a doctor or a nurse in the last 12 months [28] |

| National institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH-DISC, version IV): A structured diagnostic interview administered by lay interviewers to assess diagnostic criteria for mental disorders in children and adolescents, in accordance with the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) [49] |

| CIDI-SF: 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD), based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview–Short Form [50,51] |

| The university of Michigan composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI): A highly structured research diagnostic instrument developed for use by trained lay interviewers to assess the most common diagnoses among children, adolescents, and young adults as described in the DSM-III-R [52,53] |

| A 6-item question: During the past 3-month how often you have felt too tired to do things; had trouble going to sleep or staying asleep; felt unhappy, sad or depressed; felt hopeless about the future; felt nervous or tense; worried too much about things [54] |

| Major depressive episode diagnosis: self-reported depression diagnosed by a medical professional with the past year [26] |

| The short-form (36) health survey (SF-36) [55] |

| Mental health component of national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), assess diagnostic criteria for mental disorders in children and adolescents, in accordance with the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, third edition (DSM-III) [31,56] |

| Anxiety |

| Social interaction anxiety scale (SIAS) [29,30,57,58] |

| Diagnostic interview schedule for children, version IV (DISC-IV) [26,35,59] |

| Primary care evaluation of mental disorders (PRIME-MD) [36] |

| Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS) [34,60] |

| Anxiety medication prescribed by a doctor or a nurse in the last 12 months [28] |

| National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview for children (NIMHD) [49] |

| Alcohol |

| Ever drinkers: Drinking at least once within a lifetime [52] |

| Light drinkers: Consuming less than three drinks per week [31] |

| Moderate drinkers: Drinking without engaging in heavy episodic or binge drinking in the past two weeks [55] |

| Moderate drinkers: Drinking no more than 1 to 2 drinks per occasion in the past year, and no intoxication or heavy drinking in the past year [26,44] |

| Moderate to heavy drinkers: Consuming more than 3 drinks per week [31] |

| Regular drinkers: Drink at least once a month or more frequently and consume at least three to four drinks when drinking [48] |

| Current drinkers: Drinking at least one time during the past 30 days [33] |

| Daily drinking questionnaire (DDQ): The total number of standard alcoholic drinks consumed during the past week by summing the number of drinks reported for each day [29] |

| Frequent/heavy drinkers: Those who over the past 6 months had a drink at least once a week or had been drunk at least once [59] |

| Binge drinkers: Men/women as drinking five/four or more drinks per drinking occasion at least once in the past two weeks [26,32,33,44,51,55,57] |

| Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) [29,58] |

| Diagnostic interview schedule for children, version IV, alcohol use disorder (DISC-IV, AUD) [35] |

| Primary care evaluation for mental disorders, alcohol use disorder (PRIME-MD, AUD) [36] |

| Longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation and structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, non-patient version, alcohol use disorder (LIFE and SCID-I/NP, AUD) [60] |

| Cannabis |

| Ever cannabis users: Using cannabis at least once within a lifetime [45,52] |

| Any use of cannabis or hashish in the past six months [50] |

| Infrequent cannabis users: Using cannabis at least once per year but not more than once per month [56] |

| Infrequent cannabis users: Less than weekly cannabis use [30] |

| Frequent cannabis users: Weekly or more cannabis use [30] |

| Current cannabis users: Cannabis use at least one time during the past 30 days [27,32,33,40] |

| The substance abuse module of the composite international diagnostic interview, cannabis use disorder (CIDI-SAM, CUD) [35,36,53,56,60] |

| Tobacco |

| Ever smokers: Smoking at least once within a lifetime [34,37,38,39,52] |

| Current smokers: Smoking at least one time during the past 30 days [25,31,32,33,40,41,42,43,46,47] |

| Regular smokers: Smoking several cigarettes or more per week [48] |

| Regular smokers: Self-report measure: I’m a regular smoker/I’m a heavy smoker [28] |

| Daily smokers: Daily consumption of cigarettes or cigars for a continuous 30-day period or longer [28,34,50,51,59] |

Author Contributions

J.M., S.E., Y.B., and L.T. were involved in the study conception and design. J.M. and S.E. were responsible for the data analysis. All authors contributed to the discussion, interpreted the findings, helped write and reviewed/edited the manuscript for intellectual content, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by an internal grant from the School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pearson C., Janz T., Ali J. Health at a Glance: Mental and Substance Use Disorders in Canada. Statistics Canada; Ottawa, Canada: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteford H.A., Ferrari A.J., Degenhardt L., Feigin V., Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: An analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse Substance Abuse in Canada: Youth in Focus. [(accessed on 9 September 2018)]; Available online: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011521-2007-e.pdf.

- 4.Kessler R.C., Amminger G.P., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Alonso J., Lee S., Ustün T.B. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueser K.T., Drake R.E., Wallach M.A. Dual diagnosis: A review of etiological theories. Addict. Behav. 1998;23:717–734. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse Substance Abuse in Canada: Concurrent Disorders. [(accessed on 9 September 2018)]; Available online: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011811-2010.pdf.

- 7.World Health Organization Caring for Children and Adolescents with Mental Disorders: Setting WHO Directions. [(accessed on 9 September 2018)]; Available online: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/785.pdf.

- 8.Bitsko R.H., Holbrook J.R., Ghandour R.M., Blumberg S.J., Visser S.N., Perou R., Walkup J.T. Epidemiology and impact of health care provider-diagnosed anxiety and depression among US children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2018;39:395–403. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health Agency of Canada Chapter 3: The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2011—The Health and Well-Being of Canadian Youth and Young Adults. [(accessed on 10 September 2018)]; Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/chief-public-health-officer-report-on-state-public-health-canada-2011/chapter-3.html.

- 10.Demyttenaere K., Bruffaerts R., Posada-Villa J., Gasquet I., Kovess V., Lepine J., Angermeyer M.C., Bernert S., Morosini P., Polidori G., et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes A., Silvestri R. Rates of mental illness and associated academic impacts in Ontario’s College students. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2016;31:27–46. doi: 10.1177/0829573515601396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher M., Prinstein M.J., Simon V., Spirito A. Social anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation in a clinical sample of early adolescents: Examining loneliness and social support as longitudinal mediators. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014;42:871–883. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9844-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shrier L.A., Harris S., Sternberg M., Beardslee W.R. Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Prev. Med. 2001;33:179–189. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serafini G., Muzio C., Piccinini G., Flouri E., Ferrigno G., Pompili M., Girardi P., Amore M. Life adversities and suicidal behavior in young individuals: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2015;24:1423–1446. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0760-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel V., Flisher A.J., Hetrick S., McGorry P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369:1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Canada Canadian Tobacco Alcohol and Drugs (CTADS): 2015 Summary. [(accessed on 9 September 2018)]; Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2015-summary.html.

- 17.Banken J.A. Drug abuse trends among youth in the United States. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2004:465–471. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nock M.K., Green J.G., Hwang I., McLaughlin K.A., Sampson N.A., Zaslavsky A.M., Kessler R.C. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Townsend L., Flisher A.J., King G. A systematic review of the relationship between high school dropout and substance use. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2007;10:295–317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: A review of the literature (1990–2010) Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:4–27. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchwood T.D., Ford H., DeCoster J., Sutton M., Lochman J.E. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2015;52:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan C.J., Andersen S.L. Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017;25:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadock B.J., Sadock V.A., Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khantzian E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung S.S., Joung K.H. Risk factors for current smoking among American and South Korean adolescents. 2005–2011. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2014;46:408–415. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter L., Pugh B.S., Peters E.A., Vaughan R.D., Foster S.E. Underage drinking: Prevalence and correlates of risky drinking measures among youth aged 12–20. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42:385–394. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1102923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasic D., Weerasinghe S., Asbridge M., Langille D.B. Longitudinal associations of cannabis and illicit drug use with depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempts among Nova Scotia high school students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;129:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grunau G.L., Ratner P.A., Hossain S., Johnson J.L. Depression and anxiety as possible mediators of the association between smoking and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2010;8:595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11469-009-9244-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villarosa M.C., Madson M.B., Zeigler-Hill V., Noble J.J., Mohn R.S. Social anxiety symptoms and drinking behaviors among college students: The mediating effects of drinking motives. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014;28:710–718. doi: 10.1037/a0036501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckner J.D., Schmidt N.B. Marijuana effect expectancies: Relations to social anxiety and marijuana use problems. Addict. Behav. 2008;33:1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanna E.Z., Yi H.Y., Dufour M.C., Whitmore C.C. The relationship of early-onset regular smoking to alcohol use, depression, illicit drug use, and other risky behaviors during early adolescence: Results from the youth supplement to the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Subst. Abuse. 2001;13:265–282. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts S.J., Glod C.A., Kim R., Hounchell J. Relationships between aggression, depression, and alcohol, tobacco: Implications for healthcare providers in student health. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2010;22:369–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubik M.Y., Lytle L.A., Birnbaum A.S., Murray D.M., Perry C.L. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in young adolescents. Am. J. Health Behav. 2003;27:546–553. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.27.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin R.D., Lewinsohn P.M., Seeley J.R. Cigarette smoking and panic attacks among young adults in the community: The role of parental smoking and anxiety disorders. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts R.E., Roberts C.R., Xing Y. Comorbidity of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents: Evidence from an epidemiologic survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S4–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low N.C., Lee S.S., Johnson J.G., Williams J.B., Harris E.S. The association between anxiety and alcohol versus cannabis abuse disorders among adolescents in primary care settings. Fam. Pract. 2008;25:321–327. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss J.W., Mouttapa M., Chou C.P., Nezami E., Johnson C.A., Palmer P.H., Cen S., Gallaher P., Ritt-Olson A., Azen S., et al. Hostility, depressive symptoms, and smoking in early adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2005;28:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendel J.R., Berg C.J., Windle R.C., Windle M. Predicting young adulthood smoking among adolescent smokers and non-smokers. Am. J. Health Behav. 2012;36:542–554. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munafò M.R., Hitsman B., Rende R., Metcalfe C., Niaura R. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. 2008;103:162–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridner S.L., Staten R.R., Danner F.W. Smoking and depressive symptoms in a college population. J. Sch. Nurs. 2005;21:229–235. doi: 10.1177/10598405050210040801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duncan B., Rees D.I. Effect of smoking on depressive symptomatology: A re-examination of data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005;162:461–470. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman E., Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000;106:748–755. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lechner W.V., Janssen T., Kahler C.W., Audrain-McGovern J., Leventhal A.M. Bi-directional associations of electronic and combustible cigarette use onset patterns with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Prev. Med. 2017;96:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paschall M.J., Freisthler B., Lipton R.I. Moderate alcohol use and depression in young adults: Findings from a national longitudinal study. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95:453–457. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.030700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suerken C.K., Reboussin B.A., Sutfin E.L., Wagoner K.G., Spangler J., Wolfson M. Prevalence of marijuana use at college entry and risk factors for initiation during freshman year. Addict. Behav. 2014;39:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martini S., Wagner F.A., Anthony J.C. The association of tobacco smoking and depression in adolescence: Evidence from the United States. Subst. Use Misuse. 2002;37:1853–1867. doi: 10.1081/JA-120014087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg C., Choi W.S., Kaur H., Nollen N., Ahluwalia J.S. The roles of parenting, church attendance, and depression in adolescent smoking. J. Community Health. 2009;34:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simantov E., Schoen C., Klein J.D. Health-compromising behaviors: Why do adolescents smoke or drink? Identifying underlying risk and protective factors. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000;154:1025–1033. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.10.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson A., He J.P., Curry L., Merikangas K. Cigarette smoking and mood disorders in U.S. adolescents: Sex-specific associations with symptoms, diagnoses, impairment and health services use. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012;72:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Georgiades K., Boyle M.H. Adolescent tobacco and cannabis use: Young adult outcomes from the Ontario Child Health Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2007;48:724–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naicker K., Galambos N.L., Zeng Y., Senthilselvan A., Colman I. Social, demographic, and health outcomes in the 10 years following adolescent depression. J Adolesc. Heal. 2013;52:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brook D.W., Brook J.S., Zhang C., Cohen P., Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harder V.S., Stuart E.A., Anthony J.C. Adolescent cannabis problems and young adult depression: Male-female stratified propensity score analyses. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;168:592–601. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Loughlin J., O’Loughlin E.K., Wellman R.J., Sylvestre M.P., Dugas E.N., Chagnon M., Dutczak H., Laguë J., McGrath J.J. Predictors of cigarette smoking initiation in early, middle, and late adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health. 2017;61:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weitzman E.R. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004;192:269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marmorstein N.R. Anxiety disorders and substance use disorders: Different associations by anxiety disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meade E.A., Woolaway-Bickel K., Schmidt N.B. Social anxiety and alcohol use: Evaluation of the moderating and mediating effects of alcohol expectancies. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004;18:33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strahan E.Y., Panayiotou G., Clements R., Scott J. Beer, wine, and social anxiety: Testing the “self-medication hypothesis” in the US and Cyprus. Addict. Res. Theory. 2011;19:302–311. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2010.545152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu P., Goodwin R.D., Fuller C., Liu X., Comer J.S., Cohen P., Hoven C.W. The relationship between anxiety disorders and substance use among adolescents in the community: Specificity and gender differences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9385-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buckner J.D., Schmidt N.B., Lang A.R., Small J.W., Schlauch R.C., Lewinsohn P.M. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wells G., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa Health Research Institute; Ottawa, ON, Canada: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hedges L.V., Vevea J.L. Fixed and random effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods. 1998;3:486–504. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chaiton M.O., Cohen J.E., O’Loughlin J., Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore T.H., Zammit S., Lingford-Hughes A., Barnes T.R., Jones P.B., Burke M., Lewis G. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kedzior K.K., Laeber L.T. A positive association between anxiety disorders and cannabis use or cannabis use disorders in the general population- a meta-analysis of 31 studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Windle M. Alcohol use among adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Res. Health. 2003;27:79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brière F.N., Rohde P., Seeley J.R., Klein D., Lewinsohn P.M. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Compr. Psychiatry. 2014;55:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rohde P., Lewinsohn P.M., Kahler C.W., Seeley J.R., Brown R.A. Natural course of alcohol use disorders from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lev-Ran S., Roerecke M., Le Foll B., George T.P., McKenzie K., Rehm J. The association between cannabis use and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Med. 2014;44:797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Degenhardt L., Hall W., Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98:1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]