Abstract

Background

While statins may have anti-inflammatory effects, anti-oxidative effects are controversial. We investigated if statin treatment is associated with differences in oxidatively generated nucleotide damage and chronic inflammation, and the relationship between nucleotide damage and chronic inflammation.

Methods

We included 19,795 participants from the Danish General Suburban Population Study. In 3420 participants, we measured urinary 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as markers of oxidatively generated damage to DNA and RNA, respectively. We used a composite score for chronic inflammation (INFLA score) of hsCRP, WBC, platelet count, and neutrophil granulocyte to lymphocyte ratio. Associations were assessed using multivariate linear regression models.

Results

Compared with non-users, statin users had 4.3–6.0% lower 8-oxodG in three separate models (p < 0.05); there were no differences in 8-oxoGuo. Among participants aged > 60 y, statin users had 11.4% lower 8-oxodG (95%CI: 6.7–15.9%, pinteraction<0.001) and 3.9% lower 8-oxoGuo (95%CI: 0.1–7.5%, pinteraction = 0.002), compared with non-users. Compared with non-users, statin users had 11.1% (95%CI: 5.4–16.5%, pinteraction<0.001) lower 8-oxodG in participants treated for hypertension, and 18.6% (95%CI: 6.8–28.9%, pinteraction<0.001) lower 8-oxodG in participants with decreased renal function. Compared with non-users, statin users had significantly lower INFLA score (p < 0.001). 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo associated positively with markers of chronic inflammation.

Conclusions

Oxidatively generated DNA damage and inflammatory burden are lower in statin users compared with non-users. Together, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects may contribute to the beneficial effects of statins.

Abbreviations: 8-oxodG, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine; 8-oxoGuo, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ROS, reactive oxidative stress; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; RCT, randomized clinical trials; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; GESUS, The Danish General Suburban Population Study; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist to hip ratio; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SD, standard deviation

Keywords: Statins, Oxidative stress, Inflammation, Cardiovascular disease, Biomarker

Highlights

-

•

Statin users have lower oxidatively generated DNA damage than non-users.

-

•

The protective effect of statins is more pronounced in high-risk groups.

-

•

Statin users have lower levels of chronic inflammation than non-users.

1. Introduction

Statin treatment reduces the risk of cardiovascular events and death [1]. This effect is mainly due to improvement of cholesterol levels, but may also be mediated by pleiotropic effects of statins decreasing chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [2], [3]. Oxidative stress is defined as an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their elimination by anti-oxidants [4].

Markers of oxidatively generated DNA and RNA damage, as measures of intranuclear and cytosolic oxidative damage, may have clinical relevance as markers of total systemic reactive oxidative stress [4]. Oxidatively generated damage to DNA and RNA can be quantified in urine by measuring 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine (8-oxoGuo), respectively, by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [4]. The exact source of 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo is still debatable. However, the current acceptable interpretation is that they reflect the rate of guanine oxidation in the nucleic acids and their precursor pools [5], [6], [7], [8]. Increased levels of 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo are associated with aging, smoking, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and certain cancers [4], [9], [10], [11], [12].

While studies in vivo have shown that statin treatment has anti-inflammatory effects [2], [13], data on their anti-oxidative effects in vivo are ambiguous. Anti-oxidative effects of statins have been reported in numerous studies, while other studies have shown no such effects (Supplemental table S1) [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Notably, several different methods have been used to assess the level of oxidative stress, and there are concerns regarding the validity, specificity and clinical relevance of some of these [4]. Furthermore, these studies have been relatively small, being powered to detect relatively large effects of statin treatment. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins have also been observed as decreases in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels and white blood cell count (WBC) [2], [13], [20], [21], [22], [23]. Statins may also decrease oxidative stress by reducing upstream chronic inflammation [24].

We investigated the differences in oxidatively generated nucleotide damage and chronic inflammation between statin users and non-users in participants from the Danish General Suburban Population Study (GESUS).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study setting

GESUS is a cross-sectional study of the adult population in a suburban municipality in Denmark. Participants were included 2010–2013 [25]. All individuals aged > 30 y and a random 25% selection of the population aged 20–30 y were invited. Participation rate was 43%; median age was 56 y. One of the main objectives of the study was to identify risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (SJ-114 amendment 4) and the Danish Data Protection Agency. The principles of The Declaration of Helsinki were abided by. Participants gave written informed consent.

2.2. Study population

All participants in GESUS (n = 21,205) were evaluated. Since our aim was to investigate associations with chronic inflammation, all participants suspected of having an acute inflammatory reaction were excluded by the following criteria: hsCRP > 10 mg/l or WBC > 20 × 109/L or WBC < 3 × 109/L or missing hsCRP or WBC (n = 921); 20,284 participants were included.

For analysis of the associations of statin treatment, participants without information about use of statins were excluded (n = 489), reducing the number of participants to 19,795. To investigate the associations between statin treatment and markers of oxidatively generated nucleotide damage, only participants with information on statin use who gave a urine sample were included (n = 3420). All participants who gave a urine sample (n = 3496) were included in analyses of the associations between oxidatively generated damage and inflammatory variables.

2.3. Questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire was used in GESUS [25]. Statin users were identified as participants giving a positive answer to the question “Do you daily or almost daily take medicine for high cholesterol?”. Smoking habits were reported both by smoking status (current smoker, former smoker and never smoker), and by self-reported pack years. Participants with hypertension were identified as those using antihypertensive drugs. Participants with type 1 diabetes mellitus were identified as those with diabetes diagnosed before the age of 10 y using insulin. The remaining participants with self-reported diabetes were regarded as having T2DM. A history of ischemic disease was defined as: previous acute myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease and/or stroke. The questionnaire contained no question allowing identification of patients with peripheral artery disease or other ischemic diseases. Leisure time physical activity was reported in four categories: (I) mainly passive or light activity less than 2 h/wk., (II) light activity 2–4 h/wk., (III) light activity > 4 h/wk. or more strenuous activity 2–4 h/wk., (IV) more strenuous activity > 4 h/wk.

2.4. Clinical and biochemical data

Height was measured without shoes on a stadiometer. Waist circumference was measured at the lowest rib and hip circumference at the widest part of the hip. Weight was measured on a Bio Impedance Analysis (TANITA MC-180MA; Tanita Corporation). Participants with a pacemaker and pregnant women were weighed on an ordinary digital weight scale (Tanita WB-110 MA; Tanita Corporation); 1 kg was subtracted to account for clothes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by weight/height (kg/cm2). BMI was grouped as: normal (18.5–24.9 kg/cm2), underweight (<18.5 kg/cm2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/cm2), obese cl I. (30.0–34.9 kg/cm2), obese cl. II (35.0–39.9 kg/cm2) and obese cl. III (≥40 kg/cm2). Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated as waist circumference (cm)/hip circumference (cm).

Non-fasting blood samples were drawn 15:30–21:00 and kept at 4 °C until biochemical analysis the next day. Blood for lipoproteins (total cholesterol, triglycerides), creatinine and hsCRP measurements was drawn in plasma separation tube and analyzed on Cobas-6000 (Roche Diagnostics); blood for hematology was drawn in EDTA tubes and analyzed on a Sysmex XE-5000 (Sysmex Corporation). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) was calculated using Friedewald equation. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.

Spot urine samples were collected from 3653 randomly selected participants and stored at − 80 °C. Urinary 8-oxoGuo and 8-oxodG levels were measured using ultra-performance LC-MS/MS on an Acquity UPL I-class system (Waters) and Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters) [26]. The measurements were adjusted for urinary creatinine concentration and reported in nmol/mmol creatinine.

INFLA score is a scoring system for low-grade chronic inflammation based on 10-tiles of hsCRP, WBC, platelet count, and neutrophil granulocyte to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [27]. Cut-off values are shown in Supplemental Fig. S1.

2.5. Statistical analyses

The statistical software R.3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and RStudio 1.0.136 (RStudio) were used. Summary statistics were presented as frequency and percentages for categorical data, mean and standard deviation (SD) for numeric normally distributed data, and median and interquartile range for numeric non-normally distributed data. Distributions of numerical data were visually assessed and transformed using the natural logarithm (log) accordingly. The following outcome variables were log-transformed: hsCRP, NLR, 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo (Supplemental Fig. S2).

The most frequent missing data were smoking status (5%), eGFR (4%), leisure time physical activity (2%) and information regarding ischemic diseases and T2DM (1%). We imputed missing covariate data by multiple imputation using the MICE R package [28]; outcome or explanatory variables were not imputed. The associations were assessed using multivariate linear regression models and presented in tables with forest plots. Estimates of the difference between groups, 95% confidence intervals and p-values were presented; log-transformed variables were transformed back using the exponential function. Statistical significance was defined as p-values < 0.05.

The associations between statin use and urinary 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo levels were assessed using three models. In model 1 we adjusted for: sex, age, smoking habits, LDL-C, HDL-C, BMI group, WHR, T2DM, hypertension, ischemic disease, eGFR and INFLA score. In model 2 we excluded INFLA score. In model 3 we used the variables known to affect urinary 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo levels: sex, age, smoking habits, BMI groups, WHR and T2DM. We also included LDL-C and HDL-C in all models to investigate the associations independent of cholesterol levels. Subgroup analyses were done using the third model.

The associations between statin use and inflammatory markers were assessed. Included covariates were sex, age, smoking habits, BMI, WHR, hypertension, T2DM, ischemic diseases, eGFR, LDL-C and HDL-C. In the forest plot, differences are shown in number of SDs. Subgroup analysis was done for the INFLA score.

Analysis of the associations between urinary 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo levels and inflammatory markers included the following covariates: sex, age, smoking habits, BMI, WHR, hypertension, T2DM, ischemic disease, LDL-C and HDL-C. Estimates represent differences in the oxidative marker per one SD increase in the inflammatory markers.

3. Results

In this study, 551 statin users and 2869 non-users gave a urine sample for analysis of 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo levels; their characteristics are presented in Table 1. In total, 2922 statin users, and 16,873 non-users were included for analysis of inflammatory markers; their characteristics are presented in Supplemental table S1. Descriptive results are shown in Supplemental table S2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with measurements of oxo8dG and oxo8Guo by statin use.

| Non-users (n = 2869) | Statin users (n = 551) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 1139 (40) | 266 (48) | < 0.001 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 52 (13) | 64 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoking status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 1181 (41) | 165 (30) | |

| Former | 1060 (37) | 262 (48) | |

| Smoker | 479 (17) | 101 (18) | |

| Pack years median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.0, 16.0) | 8.8 (0.0, 28.8) | < 0.001 |

| BMI groups, n (%)* | <0.001 | ||

| Normal | 1159 (40) | 147 (27) | |

| Underweight | 31 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Overweight | 1131 (39) | 253 (46) | |

| Obese cl. I | 414 (14) | 108 (20) | |

| Obese cl. II | 99 (4) | 31 (6) | |

| Obese cl. III | 29 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| Waist hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.91 (0.86) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.455 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 480 (17) | 346 (63) | < 0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 48 (2) | 100 (18) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol), median (IQR) | 37 (34, 39) | 40 (37, 43) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic disease, n (%)† | 48 (1.7) | 144 (26.1) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 30 (1.0) | 53 (9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 14 (0.5) | 63 (11.4) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%)‡ | 12 (0.4) | 67 (12.2) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer, n (%)§ | 159 (5.5) | 74 (13.4) | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 5.57 (1.01) | 4.85 (1.06) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 3.21 (0.87) | 2.41 (0.88) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 1.61 (0.49) | 1.56 (0.49) | 0.014 |

| eGFR (µmol/l), median (IQR) | 82 (72, 91) | 76 (65, 87) | < 0.001 |

| Leisure time physical activity, n (%)ǁ | 0.001 | ||

| Group I: Mainly passive activity | 149 (5) | 33 (6) | |

| Group II: Light activity | 1364 (48) | 292 (53) | |

| Group III: Moderate activity | 1159 (40) | 185 (34) | |

| Group IV: Strenous activity | 150 (5) | 22 (4) | |

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

BMI groups: Normal, 18.5–24.9 kg; Underweight, < 18.5 kg; Overweight, 25.0–29.9 kg; Obese cl. I, 30.0–34.9 kg; Obese cl. II, 35.0–39.9 kg; Obese cl. III, ≥ 40 kg.

Ischemic heart disease or prior myocardial infarction or prior stroke.

Arteriosclerosis without prior myocardial infarction.

Current or prior cancer diagnosis.

Leisure time physical activity groups: Group I, mainly passive or light activity less than 2 h /wk.; Group II, light activity 2–4 h /wk.; Group III, light activity > 4 h /wk. or more strenuous activity 2–4 h /wk.; Group IV, more strenuous activity > 4 h /wk.

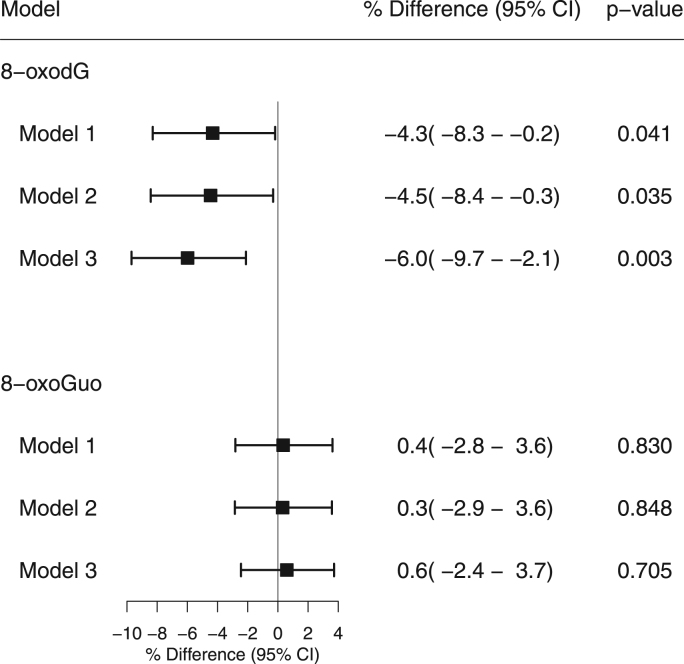

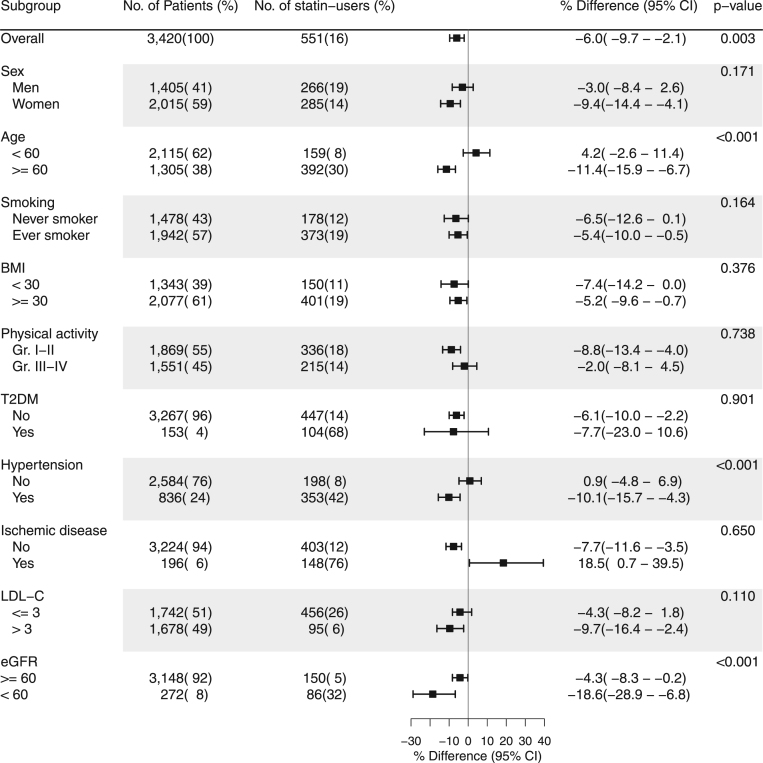

In model 1, adjusting for INFLA score along with traditional risk factors for CVD, statin users had 4.3% (95%CI: 0.2–8.3%, p = 0.041) lower 8-oxodG levels than non-users (Fig. 1). In model 2, only adjusting for traditional risk factors for CVD, statin users had 4.5% (95%CI: 0.3–8.4%, p = 0.035) lower 8-oxodG levels than non-users. In model 3, only adjusting for sex, age, smoking habits, BMI, WHR, T2DM and cholesterol levels, statin users had 6.0% (95%CI: 2.1–9.7%, p = 0.003) lower 8-oxodG levels. In subgroup analysis of model 3, we found modifications of age, hypertension and eGFR (all pinteraction<0.001) on the association between statin use and 8-oxodG levels. In participants aged ≥ 60 y, statin users had 12.5% (95%CI: 7.9–16.9%) lower 8-oxodG levels than non-users. In participants treated for hypertension, statin users had 11.1% (95%CI: 5.4–16.5%) lower 8-oxodG levels than non-users. In participants with eGFR < 60 µmol/l, the levels of 8-oxodG statin users were 18.6% (95%CI: 6.8–28.9%) lower than those of non-users (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Relative difference in creatinine adjusted 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo between statin users and non-users by multivariate liner regression models. A negative % difference represents a lower value of creatinine adjusted 8-oxodG/8-oxoGuo in statin users compared to non-users. Model 1: adjusted for sex, age, smoking habits, LDL-C, HDL-C, BMI, hip-waist ratio, T2DM, hypertension, ischemic disease, eGFR, INFLA score. Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, smoking habits, LDL-C, HDL-C, BMI, hip-waist ratio, T2DM, hypertension, ischemic disease, eGFR. Model 3: adjusted for sex, age, smoking habits, LDL-C, HDL-C, BMI, hip-waist ratio, T2DM.

Fig. 2.

Subgroup analysis of the relative difference in creatinine adjusted 8-oxodG between statin users and non-users with significance level of interaction by multivariate linear regression models. A negative % difference represents a lower value of creatinine adjusted 8-oxodG in statin users compared to non-users. P-value < 0.05 represents a significant interaction. The association is adjusted for: sex, age, smoking habits, LDL-C, HDL, BMI, hip-waist ratio, T2DM. BMI is in kg/m2. Leisure time physical activity groups: Group I, mainly passive or light activity less than 2 h/wk.; Group II, light activity 2–4 h/wk.; Group III, light activity > 4 h/wk. or more strenuous activity 2–4 h/wk.; Group IV, more strenuous activity > 4 h/wk. LDL-C is in mmol/l. eGFR is in µmol/l. BMI, body mass index; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The 8-oxoGuo levels did not differ between the groups in the entire population (Fig. 1). In the subgroup analysis, we found modifications of age (pinteraction = 0.002) on the association between statin use and 8-oxoGuo levels. In participants aged ≥ 60 y, statin users had 4.4% (95%CI: 0.8–8.0) lower 8-oxoGuo levels than non-users (Supplemental Fig. S3).

No differences were found between long term use of statins (>1 y) and short-term use of statins (≤1 y) with respect to 8-oxodG (difference: −2.2%, 95%CI: −9.5 to 5.7%, p = 0.573) and 8-oxoGuo levels (difference: −3.9%, 95%CI: −9.4 to 1.9%, p = 0.179).

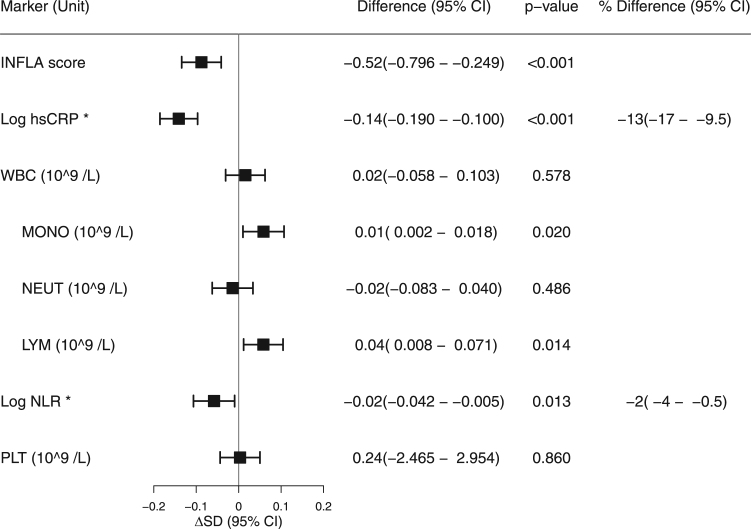

Compared with non-users, the INFLA score of statin users was 0.49 (95%CI 0.22–0.76, p < 0.001) lower. Compared with non-users, statin users had 13% (95%CI: 9–16%, p < 0.001) lower hsCRP, 0.01 109/L (95%CI: 0.00–0.02, p = 0.009) higher monocyte count, 0.05 109/L (95%CI: 0.02–0.09, p < 0.001) higher lymphocyte count and 3% (95%CI: 1–5%, p = 0.003) lower NLR. We found no difference between the groups with respect to WBC, neutrophil or platelet count (Fig. 3). In subgroup analysis, we found that the association between statin use and INFLA score was modified by BMI (pinteraction= 0.010), LDL-C (pinteraction= 0.049) and eGFR (pinteraction= 0.038). The biggest differences were observed in participants with BMI ≥ 30 kg/cm2, participants with LDL-C ≤ 3 mmol/L and participants with eGFR < 60 µmol/l (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Difference in inflammatory markers between statin users and non-users by multivariate linear regression models. A negative difference represents a lower value of the marker in statin users compared to non-users. ΔSD: standard deviation difference in markers between statin users and non-users. The models were adjusted for gender, age, smoking habits, BMI, hip-waist ratio, hypertension, T2DM, ischemic disease, LDL-C, HDL-C, physical activity and eGFR. *hsCRP and NLR are log transformed. The difference presented in the forest plot is difference in the log values. Percentage differences in the groups are shown to the right. hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell count; MONO, monocyte count; NEUT, neutrophil granulocyte count; LYM, lymphocyte count; NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PLT, platelet count.

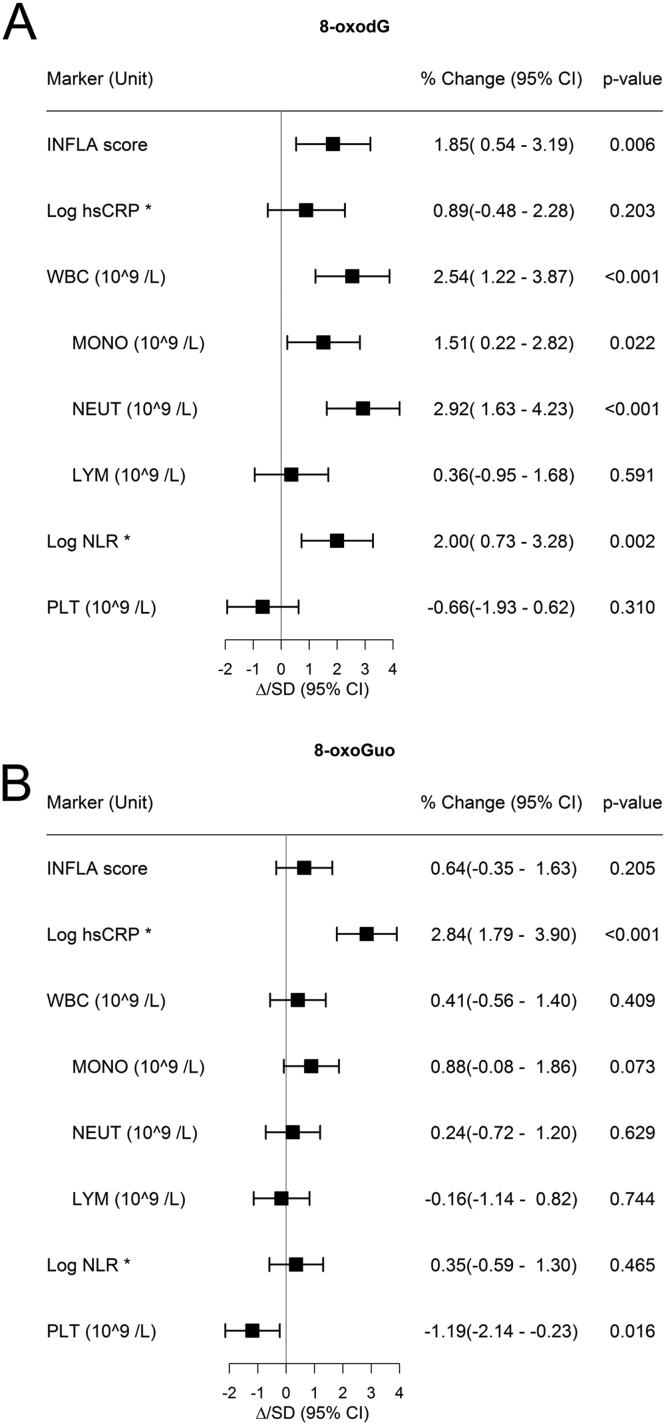

8-oxodG was positively associated with INFLA score, WBC, monocyte count, neutrophil count and NLR, but not with hsCRP, lymphocyte count or platelet count (Fig. 4A). 8-oxoGuo was positively associated with hsCRP, but not with INFLA score or other components of the INFLA score (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Relative change in creatinine adjusted 8-oxodG (A) and 8-oxoGuo (B) pr. one standard deviation increase in inflammatory markers by multivariate linear regression models. A: association between inflammatory markers and creatinine adjusted 8-oxodG; B: association between inflammatory markers and creatinine adjusted 8-oxoGuo. The estimate is % change of 8-oxodG pr. one unit increase in the inflammatory markers. The plot illustrates change in 8-oxodG/8-oxoGuo pr. standard deviation change in inflammatory markers. The models were adjusted for sex, age, smoking habits, BMI, hip-waist ratio, hypertension, T2DM, ischemic disease, LDL-C, HDL-C and eGFR. * hsCRP and NLR are log transformed. The difference presented in the forest plot is difference in the log values. hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell count; MONO, monocyte count; NEUT, neutrophil granulocyte count; LYM, lymphocyte count; NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PLT, platelet count.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional general population study, we examined the associations between statin treatment, oxidatively generated DNA and RNA damage, and markers of chronic inflammation.

In three separate models, we found that urinary 8-oxodG levels of statin users were 4.3–6.0% lower than those of non-users, indicating that statins decrease oxidatively generated DNA damage. The significant differences, both before and after exclusion of the INFLA score, suggests that anti-inflammatory mechanisms contribute to, but are not solely responsible for, the protective effect of statins on DNA damage. This finding is supported by the association between urinary 8-oxodG levels and INFLA score observed in our study, and between 8-oxodG levels and inflammatory markers in other smaller studies using ELISA measurements of 8-oxodG [29], [30].

In the subgroup analyses, we found that statin treatment had the greatest protective effect on DNA damage in participants aged ≥ 60 y, in participants with hypertension and in participants with decreased renal function. Moreover, in participants aged ≥ 60 y statins also had a protective effect on RNA damage. These results indicate that the anti-oxidative effects of statins are most prominent in individuals with higher levels of oxidative stress, which is associated with aging, hypertension and decreased renal function [9], [11], [31]. Interestingly, antihypertensive treatment has been shown to decrease urinary 8-oxodG levels, and the interaction observed in our study may reflect a synergistic effect between the antihypertensive treatment and statins [11].

Two RCTs did not find an effect of statin treatment on oxidatively generated nucleotide damage. Rasmussen et al. found no effects of statin treatment on urinary 8-oxoGuo or 8-oxodG levels in healthy men aged 18–50 y [19]. Likewise, we found no differences in 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo levels between statin users and non-users in participants aged < 60 y or in participants without hypertension (Fig. 2), implying a limited effect of statins on oxidatively generated nucleotide damage in otherwise healthy individuals. Notably, their study was powered toward a 20% difference and 8-oxodG levels were about 4% lower in the statin group, which is like the difference observed in our study. Additionally, Scheffer et al. found no significant change in 8-oxodG levels after 12 wks. of treatment with atorvastatin or simvastatin in individuals at high risk of CVD, although nominal reductions of 6% and 16% were observed [18]. No power analysis was reported in that study. We performed a post-hoc power analysis based on the SD of change in 8-oxodG levels published [18], a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. We found that their study was powered to detect differences larger than 27%.

Supporting our findings, Abe et al. found that rosuvastatin treatment for 6 mos. decreased urinary 8-oxodG levels, measured with ELISA, by 15% in individuals with diabetic nephropathy compared with placebo [17], which is similar to our findings in participants with decreased renal function. 8-oxodG has frequently been measured by ELISA. This method lacks specificity and sensitivity, and results based on this method should be interpreted with caution [4], [5]. In a European study, the ELISA method had higher inter-laboratory and -individual variability than LC-MS/MS, and the agreement between ELISA and LC-MS/MS was poor [32].

We observed differential effects on DNA and RNA oxidation, a phenomenon also observed after intervention with olive oil [33]. A recent study also found such a differential effect in diseases, however, favoring RNA oxidation as a marker [6]. The underlying mechanisms for the differences between DNA and RNA oxidation are not known in detail, and the exact origin of the oxidized nucleotides is still unclear [7], [8]. Some of the differences may relate to the localization of RNA in the cytosol and DNA in the nucleus and to the single strand properties of RNA, versus the double strand properties of DNA and it protective histone proteins [6]. Also, the sources of free radical production from different sites within the cells may have differential effects on the markers, e.g. mitochondria versus endoplasmatic reticulum, and reactive iron structures located in the cytosol [6]. It is unknown whether statins have differential antioxidative effects in different locations within the cell. However, statin treatment is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle cells, induced by a decrease in coenzyme Q10 [34]. Mitochondrial dysfunction could result in increased oxidatively generated damage to RNA [34]. The measurements represent an average oxidatively generated nucleotide damage in all tissues of the organism [5]. Therefore, the effect on 8-oxoGuo by increased oxidation in the muscles due to mitochondrial dysfunction may attenuate a possible antioxidative effect of statins in other tissues, when using this method.

Taken together, our findings indicate that statins influence oxidatively generated DNA damage with increasing age. Moreover, anti-oxidative effects of statins may be more beneficial in some high-risk groups. Indeed, anti-inflammatory effects of statins, measured as a decrease in hsCRP levels, is markedly bigger in secondary prevention trials compared with primary prevention trials and general population studies [13], [20], [21], [22], [23].

Statins may protect the vascular system from oxidative damage. In the CLARICOR study two wks. of clarithromycin treatment, in individuals with ischemic heart disease, increased long-term mortality primarily due to increased cardiovascular mortality [35], possibly due to increased oxidatively generated damage [36]. Indeed, in a RCT, one week of clarithromycin treatment resulted in increases of 22% in urinary 8-oxodG levels and 15% in urinary 8-oxoGuo levels [36]. In later subgroup analysis of the CLARICOR study the negative effect was attenuated in individuals receiving statin at baseline, implying a protective effect of statins [37]. Also, in individuals with chronic kidney disease, associated with increased oxidative stress [31], statins reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality [38]. Conversely, anti-inflammatory effects of statins could also explain these findings.

In our study, statin users had about half a point lower INFLA score than non-users. This difference was primarily due to lower values of hsCRP and a small difference in NLR. Bonaccio et al. has shown an association between higher INFLA score and increased risk of all-cause mortality [39]; interestingly, hsCRP and NLR were the most important components of this association. Furthermore, an elevated level of hsCRP is an established risk factor for CVD [40], [41]. Our findings in this respect are supported by other similar general population studies [20], [21], [22], [23]. This implies that our study population and statistical models are comparable to other large general population studies.

A strength of our study is the inclusion of a very large population in a municipality with both urban and rural areas [25]. It is the first general population study to investigate the associations of statin treatment with markers of oxidatively generated RNA and DNA damage, and it is currently the largest general population study to investigate the effect of statin treatment on biochemical markers of inflammation. Importantly, the study has power to detect smaller differences in 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo than previous clinical studies have had. Furthermore, we used validated biomarkers of oxidatively generated nucleotide damage. Detailed information on confounders was available for this study.

Some limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, a cross-sectional design is not optimal for measuring effects of an intervention; we cannot infer causality on associations. Consequently, the reported associations and estimates should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, confounding by indication could be a limitation. Statin users are inherently different from non-users (Table 1), and after adjustment for confounders the differences observed might be affected by better health-related behavior in statin users, e.g. better compliance or more aggressive treatment regimes. Thirdly, statin use was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire asking about medication use for elevated cholesterol levels. Some participants might not know the indication for all medications used. Consequently, these participants, who possibly had increased levels of inflammation and oxidatively generated damage, may erroneously be included in the non-user group. Moreover, we have no information about different types and doses of statins. In 2010–2013, the water-soluble types simvastatin and atorvastatin together accounted for approximately 90% of prescriptions on lipid-lowering drugs in Denmark, while the lipid-soluble type rosuvastatin accounted for most of the rest [42]; however, we did not have information on particular subtypes of lipid modifying agents. Although, users of lipid-lowering drugs, other than statins, may have been included, 98% of lipid-lowering drugs prescribed were statins, according to the Danish Drug Statistics Register (www.medstat.dk) for 2010–2013, so this source of error is but minor.

Levels of 8-oxoGuo seem to discriminate patients with T2DM for premature death [43], but the clinical prognostic validity and utility of the biomarker is still unclear, and needs to be investigated in large follow-up studies.

5. Conclusions

Oxidatively generated DNA damage and inflammatory burden are lower in statin users compared with non-users. Together, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects may contribute to the beneficial effects of statins.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Trine Henriksen and Katja Luntang in the measurements of 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGuo.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

ALS was supported by a grant from Region Zealand (13-000849). The Danish General Suburban Population Study was funded by the Region Zealand Foundation, Naestved Hospital Foundation, Naestved commune, Johan and Lise Boserup Foundation, TrygFonden, Johannes Fog's Foundation, Region Zealand, Naestved Hospital, The National Board of Health, and the Local Government Denmark Foundation.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2018.101088.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Baigent C., Blackwell L., Emberson J., Holland L.E., Reith C., Bhala N., Peto R., Barnes E.H., Keech A., Simes J., Collins R. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oesterle A., Laufs U., Liao J.K. Pleiotropic effects of statins on the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2017;120:229–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridker P.M., Cannon C.P., Morrow D., Rifai N., Rose L.M., McCabe C.H., Pfeffer M.A., Braunwald E., Pravastatin or Atorvastatin E., Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction I. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. New Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:20–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frijhoff J., Winyard P.G., Zarkovic N., Davies S.S., Stocker R., Cheng D., Knight A.R., Taylor E.L., Oettrich J., Ruskovska T., Gasparovic A.C., Cuadrado A., Weber D., Poulsen H.E., Grune T., Schmidt H.H., Ghezzi P. Clinical Relevance of biomarkers of oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015;23:1144–1170. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulsen H.E., Nadal L.L., Broedbaek K., Nielsen P.E., Weimann A. Detection and interpretation of 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGua in urine, plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih Y.M., Cooke M.S., Pan C.H., Chao M.R., Hu C.W. Clinical relevance of guanine-derived urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress, determined by LC-MS/MS. Redox Biol. 2018;20:556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans M.D., Mistry V., Singh R., Gackowski D., Rozalski R., Siomek-Gorecka A., Phillips D.H., Zuo J., Mullenders L., Pines A., Nakabeppu Y., Sakumi K., Sekiguchi M., Tsuzuki T., Bignami M., Olinski R., Cooke M.S. Nucleotide excision repair of oxidised genomic DNA is not a source of urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;99:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans M.D., Saparbaev M., Cooke M.S. DNA repair and the origins of urinary oxidized 2′-deoxyribonucleosides. Mutagenesis. 2010;25:433–442. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob K.D., Noren Hooten N., Trzeciak A.R., Evans M.K. Markers of oxidant stress that are clinically relevant in aging and age-related disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2013;134:139–157. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loft S., Vistisen K., Ewertz M., Tjonneland A., Overvad K., Poulsen H.E. Oxidative DNA damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine excretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:2241–2247. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinosa O., Jimenez-Almazan J., Chaves F.J., Tormos M.C., Clapes S., Iradi A., Salvador A., Fandos M., Redon J., Saez G.T. Urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG), a reliable oxidative stress marker in hypertension. Free Radic. Res. 2007;41:546–554. doi: 10.1080/10715760601164050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Minno A., Turnu L., Porro B., Squellerio I., Cavalca V., Tremoli E., Di Minno M.N. 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine levels and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;24:548–555. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arevalo-Lorido J.C. Clinical relevance for lowering C-reactive protein with statins. Ann. Med. 2016;48:516–524. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2016.1197413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puccetti L., Santilli F., Pasqui A.L., Lattanzio S., Liani R., Ciani F., Ferrante E., Ciabattoni G., Scarpini F., Ghezzi A., Auteri A., Davi G. Effects of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin on thromboxane-dependent platelet activation and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su Y., Xu Y., Sun Y.M., Li J., Liu X.M., Li Y.B., Liu G.D., Bi S. Comparison of the effects of simvastatin versus atorvastatin on oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2010;55:21–25. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181bfb1df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hileman C.O., Turner R., Funderburg N.T., Semba R.D., McComsey G.A. Changes in oxidized lipids drive the improvement in monocyte activation and vascular disease after statin therapy in HIV. AIDS. 2016;30:65–73. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abe M., Maruyama N., Okada K., Matsumoto S., Matsumoto K., Soma M. Effects of lipid-lowering therapy with rosuvastatin on kidney function and oxidative stress in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2011;18:1018–1028. doi: 10.5551/jat.9084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheffer P.G., Schindhelm R.K., van Verschuer V.M., Groenemeijer M., Simsek S., Smulders Y.M., Nanayakkara P.W. No effect of atorvastatin and simvastatin on oxidative stress in patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Neth. J. Med. 2013;71:359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen S.T., Andersen J.T., Nielsen T.K., Cejvanovic V., Petersen K.M., Henriksen T., Weimann A., Lykkesfeldt J., Poulsen H.E. Simvastatin and oxidative stress in humans: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Redox Biol. 2016;9:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon S.S., Dillon C.F., Carroll M., Illoh K., Ostchega Y. Effects of statins on serum inflammatory markers: the U.S. National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2004. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2010;17:1176–1182. doi: 10.5551/jat.5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyngdoh T., Vollenweider P., Waeber G., Marques-Vidal P. Association of statins with inflammatory cytokines: a population-based Colaus study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Jong H.J., Damoiseaux J.G., Vandebriel R.J., Souverein P.C., Gremmer E.R., Wolfs M., Klungel O.H., Van Loveren H., Cohen Tervaert J.W., Verschuren W.M. Statin use and markers of immunity in the Doetinchem cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams N.B., Lutsey P.L., Folsom A.R., Herrington D.H., Sibley C.T., Zakai N.A., Ades S., Burke G.L., Cushman M. Statin therapy and levels of hemostatic factors in a healthy population: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:1078–1084. doi: 10.1111/jth.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuter S., Gupta S.C., Chaturvedi M.M., Aggarwal B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:1603–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heltberg A., Andersen J.S., Sandholdt H., Siersma V., Kragstrup J., Ellervik C. Predictors of undiagnosed prevalent type 2 diabetes - the Danish general suburban population study. Prim. Care diabetes. 2018;12:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henriksen T., Hillestrom P.R., Poulsen H.E., Weimann A. Automated method for the direct analysis of 8-oxo-guanosine and 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine in human urine using ultraperformance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pounis G., Bonaccio M., Di Castelnuovo A., Costanzo S., de Curtis A., Persichillo M., Sieri S., Donati M.B., Cerletti C., de Gaetano G., Iacoviello L. Polyphenol intake is associated with low-grade inflammation, using a novel data analysis from the Moli-sani study. Thromb. Haemost. 2016;115:344–352. doi: 10.1160/TH15-06-0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Buuren S., Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haghdoost S., Maruyama Y., Pecoits-Filho R., Heimburger O., Seeberger A., Anderstam B., Suliman M.E., Czene S., Lindholm B., Stenvinkel P., Harms-Ringdahl M. Elevated serum 8-oxo-dG in hemodialysis patients: a marker of systemic inflammation? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:2169–2173. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noren Hooten N., Ejiogu N., Zonderman A.B., Evans M.K. Association of oxidative DNA damage and C-reactive protein in women at risk for cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:2776–2784. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cachofeiro V., Goicochea M., de Vinuesa S.G., Oubina P., Lahera V., Luno J. Oxidative stress and inflammation, a link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2008:S4–S9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barregard L., Moller P., Henriksen T., Mistry V., Koppen G., Rossner P., Jr., Sram R.J., Weimann A., Poulsen H.E., Nataf R., Andreoli R., Manini P., Marczylo T., Lam P., Evans M.D., Kasai H., Kawai K., Li Y.S., Sakai K., Singh R., Teichert F., Farmer P.B., Rozalski R., Gackowski D., Siomek A., Saez G.T., Cerda C., Broberg K., Lindh C., Hossain M.B., Haghdoost S., Hu C.W., Chao M.R., Wu K.Y., Orhan H., Senduran N., Smith R.J., Santella R.M., Su Y., Cortez C., Yeh S., Olinski R., Loft S., Cooke M.S. Human and methodological sources of variability in the measurement of urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;18:2377–2391. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machowetz A., Poulsen H.E., Gruendel S., Weimann A., Fito M., Marrugat J., de la Torre R., Salonen J.T., Nyyssonen K., Mursu J., Nascetti S., Gaddi A., Kiesewetter H., Baumler H., Selmi H., Kaikkonen J., Zunft H.J., Covas M.I., Koebnick C. Effect of olive oils on biomarkers of oxidative DNA stress in Northern and Southern Europeans. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2007;21:45–52. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6328com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golomb B.A., Evans M.A. Statin adverse effects: a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs. 2008;8:373–418. doi: 10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gluud C., Als-Nielsen B., Damgaard M., Fischer Hansen J., Hansen S., Helo O.H., Hildebrandt P., Hilden J., Jensen G.B., Kastrup J., Kolmos H.J., Kjoller E., Lind I., Nielsen H., Petersen L., Jespersen C.M., Group C.T. Clarithromycin for 2 weeks for stable coronary heart disease: 6-year follow-up of the CLARICOR randomized trial and updated meta-analysis of antibiotics for coronary heart disease. Cardiology. 2008;111:280–287. doi: 10.1159/000128994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen E.L., Cejvanovic V., Kjaer L.K., Pedersen M.T., Popik S.D., Hansen L.K., Andersen J.T., Jimenez-Solem E., Broedbaek K., Petersen M., Weimann A., Henriksen T., Lykkesfeldt J., Torp-Pedersen C., Poulsen H.E. Clarithromycin, trimethoprim, and penicillin and oxidative nucleic acid modifications in humans: randomised, controlled trials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017;83:1643–1653. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen G.B., Hilden J., Als-Nielsen B., Damgaard M., Hansen J.F., Hansen S., Helo O.H., Hildebrandt P., Kastrup J., Kolmos H.J., Kjoller E., Lind I., Nielsen H., Petersen L., Jespersen C.M., Gluud C., Group C.T. Statin treatment prevents increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality associated with clarithromycin in patients with stable coronary heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2010;55:123–128. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181c87e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer S.C., Navaneethan S.D., Craig J.C., Johnson D.W., Perkovic V., Hegbrant J., Strippoli G.F. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;CD007784 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007784.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonaccio M., Di Castelnuovo A., Pounis G., De Curtis A., Costanzo S., Persichillo M., Cerletti C., Donati M.B., de Gaetano G., Iacoviello L., Moli-sani Study I. A score of low-grade inflammation and risk of mortality: prospective findings from the Moli-sani study. Haematologica. 2016;101:1434–1441. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.144055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridker P.M., Hennekens C.H., Buring J.E., Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. New Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:836–843. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridker P.M., Rifai N., Rose L., Buring J.E., Cook N.R. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. New Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1557–1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mortensen M.B., Falk E., Schmidt M. Twenty-year nationwide trends in statin utilization and expenditure in Denmark. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Broedbaek K., Koster-Rasmussen R., Siersma V., Persson F., Poulsen H.E., de Fine Olivarius N. Urinary albumin and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine as markers of mortality and cardiovascular disease during 19 years after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes - a comparative study of two markers to identify high risk patients. Redox Biol. 2017;13:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material