Abstract

Background

Malawi has the highest rate of cervical cancer globally and cervical cancer is six to eight times more common in women with HIV. HIV programmes provide an ideal setting to integrate cervical cancer screening.

Methods

Tisungane HIV clinic at Zomba Central Hospital has around 3,700 adult women receiving treatment. In October 2015, a model of integrated cervical cancer screening using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) was adopted. All women aged 20 and above in the HIV clinic were asked if they had cervical cancer screening in the past three years and, if not, were referred for screening. Screening was done daily by nurses in a room adjacent to the HIV clinic. Cold coagulation was used to treat pre-cancerous lesions. From October 2016, a modification to the HIV programme's electronic medical record was developed that assisted in matching numbers of women sent for screening with daily screening capacity and alerted providers to women with pre-cancerous lesions who missed referrals or treatment.

Results

Between May 2016 and March 2017, cervical cancer screening was performed in 957 women from the HIV clinic. Of the 686 (71%) women who underwent first ever screening, 23 (3.4%) were found to have VIA positive lesions suggestive of pre-cancer, of whom 8 (35%) had a same-day cold coagulation procedure, seven (30%) deferred cold coagulation to a later date (of whom 4 came for treatment), and 8 (35%) were referred to surgery due to size of lesion; 5/686 (0.7%) women had lesions suspicious of cancer.

Conclusion

Incorporating cervical cancer screening into services at HIV clinics is feasible. A structured approach to screening in the HIV clinic was important.

Keywords: HIV, cervical cancer, VIA screening

Introduction

Malawi has the highest prevalence of cervical cancer in the world with an age standardized rate of 75.9 per 100,0001. This accounts for 45% of all female cancers in Malawi and results in at least 1,600 deaths per year2,3. Women with HIV have 6 to 8 times increased risk of cervical cancer4,5,6. Cervical cancer is preventable with both Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccination and regular screening and treatment of pre-cancerous lesions. HPV vaccination programmes have been implemented in several African countries and a pilot project has recently been concluded in Malawi with plans for national scale up by 20197. However, even when the vaccine is made available, millions of women will be beyond the priority age of vaccination and screening this population for cervical cancer will remain crucial8. Several studies have shown that screening programmes using visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA) are feasible and acceptable in resource limited settings9,10,11,12. A study of VIA screening over 3 years in a general population of women in India demonstrated a 24% reduction in incidence of cervical cancer and a 35% reduction in cervical cancer mortality13.

VIA screening has been successfully integrated into HIV services in several countries. In Zambia, HIV infrastructure was used to offer cervical cancer screening on a national scale14. In Côte d'Ivoire, cervical cancer screening was offered to all women attending HIV services at four clinics, by means of a mobile team of midwives15. All women attending an urban HIV clinic in Botswana were offered VIA as part of the clinic's services12 and in a large HIV clinic in Lilongwe, Malawi, hypertension and cervical cancer are also screened for and managed as part of routine anti-retroviral (ART) services16.

For women who screen positive for lesions suggestive of cervical cancer, several treatment options are available. Cryotherapy has been widely used in many African countries and is the main method used in Malawi17. More recently cold coagulation has been introduced, which offers several potential advantages over cryotherapy18. For locally invasive lesions confined to the cervix but considered too large for cryotherapy or cold coagulation, other options include loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP), cold-knife conization and hysterectomy18. Cervical cancer screening programmes also detect patients with already advanced carcinoma, but treatment options for malignancies in many African countries remain limited due to lack of gynaecological oncology expertise and radiotherapy services19.

The Malawi Ministry of Health has adopted VIA as the method of screening for cervical cancer.17 When pre-cancerous lesions are detected, they are treated with cryotherapy. VIA is available at most district hospitals, but cryotherapy is often unavailable due to broken machines or lack of gas20. Although national HIV guidelines recommend that all HIV positive women receive VIA annually21, this has not been widely implemented. Cervical cancer screening had been available for many years at Zomba Central Hospital, but the service had often been poorly staffed and under-equipped, with no structured system for referring HIV positive women for cervical cancer screening.

In October 2015, Dignitas International, a medical and research organization, together with the Malawi Ministry of Health, established cervical cancer screening at the HIV clinic at Zomba Central Hospital. This was part of a broader initiative to fully integrate HIV and non-communicable disease (NCD) care where all adults accessing care in the HIV clinic are screened and treated for hypertension, diabetes and cervical cancer.22 We describe the process and outcomes of the integration of HIV care with cervical cancer screening, including innovations used and challenges encountered.

Methods

Setting

Zomba District is one of the most densely populated districts in Malawi with 670,500 inhabitants at the time of this study. The HIV clinic at Zomba Central Hospital in Malawi has over 6, 500 patients in care, of whom around 3,700 are adult women 20 years and older. It has been supported by Dignitas International since 2004 in the provision of supplementary clinical, laboratory and counseling staff and technical assistance.

Implementation of integrated cervical cancer screening at the HIV clinic

As part of the NCD integration initiative, new equipment was purchased and new staff was trained. The broken existing cryotherapy machine was replaced with a cold coagulator. Experience elsewhere in Malawi had shown the difficulties in maintaining cryotherapy equipment20 and the relative robustness of cold coagulation equipment23. Cryotherapy uses carbon dioxide gas to freeze a metal probe which is then applied to the cervix. A systematic literature review of 32 articles has found cure rates of 98.5% for all grades of pre-cancerous lesions at 12 months follow up using cryotherapy24. Cold coagulation involves using a metallic probe heated to 100–120°C (relatively low temperatures compared to other devises causing coagulation) and leads to thermal destruction of cervical tissue. Advantages of cold coagulation equipment include its small size and thus portability, minimal use of electricity and shorter time of treatment compared to cryotherapy.

Screening was conducted in a room adjacent to the HIV clinic. Screening was offered to all eligible women in HIV care by expert clients (ECs) who are patients on ART, are open about their HIV status and have shown exemplary adherence. The VIA service operates daily and is coordinated by an experienced nurse employed by Dignitas International with support from Ministry of Health nurses. HIV-uninfected women were also screened in the VIA clinic and approximately 50% of the VIA clients were HIV-uninfected. Due to the design of data collection, it was not possible to collect data on the outcomes of these HIV-uninfected women.

Although the national guidelines promoted annual VIA screening of HIV positive women21, a decision was made to initially reduce the frequency to every three years. This was believed to be more achievable with available capacity, and was in line with World Health Organisation guidelines25. At every clinic visit, all women over the age of 20 were asked for the date of their last VIA screening test. If they had never been screened, or the date was over three years ago, then VIA was offered. If the woman accepted, she was accompanied to the VIA room by an expert client. Pre-cancerous lesions found using VIA were treated with cold coagulation or if considered too large, the women were referred to a gynaecologist.

Data collection

Data were collected using the existing VIA register that was modified to enable capturing of those who attended the HIV clinic.

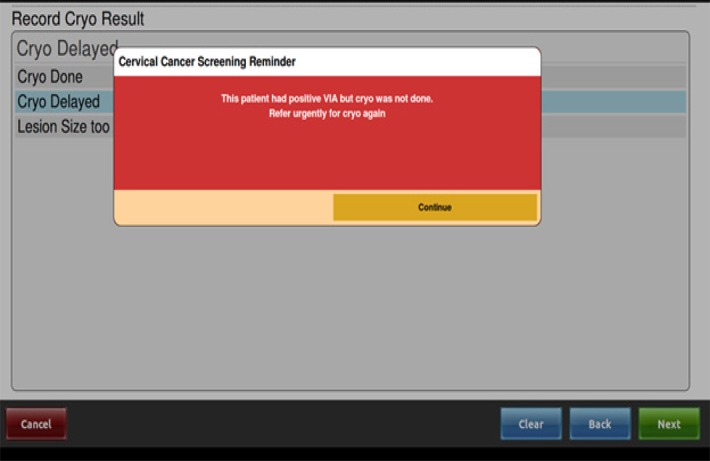

After six months of implementation, several challenges became apparent: many women referred for VIA did not attend the screening clinic or undergo screening. In addition, some women with pre-cancerous lesions elected to defer treatment with cold coagulation but did not return for care. As a response to the above two challenges, a modification to the existing HIV programme, Electronic Medical Record (EMR), was developed to incorporate VIA. This modification reminds clinicians about when VIA is due, limits daily numbers of referrals to match capacity, asks clinicians to check if women went to VIA when referred and alerts clinicians to women who had a positive VIA but did not receive same-day treatment (see figure 1). This modification was implemented in October 2016.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of VIA modification to Electronic Medical Record

Ethics approval was not sought for this study as it utilised data that is routinely collected and anonymised. The data is used in routine reporting for monitoring of service delivery of a medical program. All data can be requested from the Ministry of Health through the corresponding author.

Results

We evaluated cervical cancer screening visits in 957 women who were referred from the HIV clinic between May 2016 and March 2017. Of the 686 (71%) women who underwent first ever screening, 23(3.4%) were found to have VIA positive lesions suggestive of pre-cancer, of whom 8 (35%) had a same-day cold coagulation procedure, 7 (30%) deferred cold coagulation to a later date (of whom 4 came for treatment), and 8 (35%) were referred to surgery due to size of lesion; 5/686 (0.7%) women had lesions suspicious of cancer. Of the 23 VIA positive women, 19 (82.6%) were within age group 31–45, 3 (13%) >45 years and only 1 (4.4%) <30 years. VIA positive women (N=23) were slightly older than VIA negative women (N=615; mean age 37.7 vs. 36.9).

Comparing data from five months prior to the implementation of the modification of the EMR to six months after the intervention, the monthly average of women receiving VIA screening from the HIV clinic for the first time showed little change (from 64 to 61 women per month). However, the percentage of women who received cryotherapy the same day increased from 33% (n=3) to 83% (n=5).

Discussion

Before the implementation of the EMR modification, many women who were referred from the HIV clinic for cervical cancer screening did not undergo screening. As no women were turned away from VIA services, they likely chose not to attend VIA screening due to long waiting lines. The cervical cancer EMR is designed to match the numbers referred daily to screening capacity.The rate of testing positive for VIA, 3.4 %, is lower than reported in other services for HIV positive women in Malawi (10.4%)23, Zambia (31.8%)26 and Botswana (11.6%)12. There are several possible explanations for this. The nurse provider has many years' experience in cervical cancer screening and several studies have shown that rates of VIA positive lesions decrease over time as providers gain experience23, 26. Zomba Hospital HIV clinic has many patients who are stable on long term ART and many asymptomatic patients that have recently started ART. As such, the immune status of many in the clinic may more closely resemble those of HIV negative patients.

In order for VIA programmes to be effective, it is essential that treatment be available for pre-cancerous lesions. In particular, it is important that cryotherapy is available on the same day of diagnosis as it has been well documented that women often do not return for follow up. For example, in Zambia, 22% of women that chose to defer cryotherapy did not return for treatment27. In this regard, cryotherapy is widely known to present operational challenges because it requires large tanks of carbon-dioxide or nitrous-oxide and the freezing units can malfunction28. An audit in Malawi of VIA services at 21 facilities found that cryotherapy was working at only 7 facilities and working N2O tanks at only 5 facilities20. Cold coagulation is an alternative form of treatment to cryotherapy. In a randomized control trial, cold coagulation produced similar cure rates of 95.5% compared to 93.8% of cryotherapy29. In a meta-analysis of 4,569 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) patients treated with cold coagulation, cure rates for CIN 1 were 96% and for CIN 2 – 3 were 95%30. As cold coagulation uses electric current rather than gas, ongoing supplies are not needed and availability of same-day treatment may therefore be better ensured in resource-limited settings such as Malawi. Experience at one site in Malawi with the cold coagulator showed high acceptability with users and patients and a cure rate of 85% among 51 patients who came for follow up at one year23.

At Zomba, there has been uninterrupted availability and functioning of the cold coagulator since it was purchased in December 2015 to present. However, several women still chose not to have same-day treatment, apparently from wanting to discuss the procedure with their partners, possibly related to a recommended period of 4 weeks of sexual abstinence post treatment. This has been found in other VIA services in Malawi23. The acceptance of same-day treatment in Zomba has improved as counselling experience in the clinic has improved over time. Thus, a combination of reliable equipment and good counselling, together with the safety net of the electronic monitoring tool to catch those who chose to defer treatment, are important elements of future programme success.

Conclusions

Malawi has a large unmet need for cervical cancer screening for all women of reproductive age. Women who are HIV-positive are at significantly higher risk, and those women who regularly attend an HIV clinic are far more accessible to health care workers than women in the community. Incorporating cervical cancer screening into services at HIV clinics is, therefore, a logical strategy to reduce cervical cancer morbidity and mortality with a high benefit to screening ratio. Cervical cancer screening within an HIV clinic is feasible, although it required additional inputs of staff to run a daily service in Zomba. A structured approach to cervical cancer screening in the HIV clinic was important. This was facilitated by the modification of the EMR, which aimed to match referral numbers to screening capacity and address the previously observed attrition in the screening to treatment completion cascade. Over time, this system should result in close to universal screening of women attending the clinic. The use of cold coagulation as an alternative to cryotherapy has the potential to reduce logistical barriers to interruptions in equipment and supplies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs Lydia Chiwale and the dedicated teams at Dignitas International and Tisungane Clinic at Zomba Central Hospital for their contributions to the implementation of the project. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Sue Makin for her valuable contribution to the training and guideline review.

Authors' contributions

The authors contributed as follows: JVO conceived the project; CP, VS, BK and HA led the guideline development; JB participated in the design of the project review. AA, AM, JM and VB led design of the data analysis. CS assisted with program evaluation. CP led manuscript writing. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interests

Joep Van Oosterhout is an editorial member of the Malawi Medical Journal but he was not involved in the peer-review process of this article and did not influence the decision to have this article published. All other authors declare they have no competing interest.

Funding

Funding for the NCD-HIV integration project was provided by Grand Challenges Canada and the United States Agency for International Development. Grand Challenges Canada is funded by the Government of Canada and is dedicated to supporting Bold Ideas with Big Impact in global health.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [31 January 2018]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Msyamboza KP, Dzamalala C, Mdokwe C, Kamiza S, Lemerani M, Dzowela T, et al. Burden of cancer in Malawi; common types, incidence and trends: national population-based cancer registry. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:149. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, author. Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers: Malawi. Summary Report Update. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [31 January 2018]. Available from: http://screening.iarc.fr/doc/Human%20Papillomavirus%20and%20Related%20Cancers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clifford GM, Polesel J, Rickenbach M, Dal Maso L, Keiser O, Kofler A, et al. Cancer risk in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: associations with immunodeficiency, smoking, and highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:425–432. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serraino D, Dal Maso L, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S. Invasive cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining illness in Europe. AIDS. 2002;16:781–786. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisch M, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1500–1510. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Msyamboza KP, Mwagomba BM, Valle M, Chiuma H, Phiri T. Implementation of a human papiloma virus demonstartion project in Malawi: successes and challenges. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:599. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4526-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsu DV, Ginsburg O. The investment case for cervical cancer elimination. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2017;138(Suppl 1):69–73. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sankaranarayanan R, Rajkumar R, Esmy PO, Fayette JM, Shanthakumary S, Frappart L, et al. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of ‘see and treat’ with cryotherapy by nurses in a cervical screening study in India. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:738–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denny L, Kuhn L, De Souza M, Pollack AE, Dupree W, Wright TC., Jr Screen-and-treat approaches for cervical cancer prevention in low-resource settings: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:2173–2181. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.17.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenthal PD, Gaffikin L, Deganus S, Lewis R, Emerson M, Adadevoh S, et al. Cervical cancer prevention: safety, acceptability, and feasibility of a single-visit approach in Accra, Ghana. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e401–e408. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.031. 407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramogola-Masire D, de Klerk R, Monare B, Ratshaa B, Friedman HM, Zetola NM. Cervical cancer prevention in HIV-infected women using the “see and treat” approach in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:308–313. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182426227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankaranarayanan R, Esmy PO, Rajkumar R, Muwonge R, Swaminathan R, Shanthakumari S, et al. Effect of visual screening on cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Tamil Nadu, India. A cluster randomized trial. Lancet. 2007;370:398–406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parham GP, Mwanahamuntu MH, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Westfall A, King KE, Chibwesha C, et al. Implementation of cervical cancer prevention services for HIV-infected women in Zambia: measuring program effectiveness. HIV Ther. 2010;4:703–722. doi: 10.2217/hiv.10.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horo A, Jaquest A, Ekouevi DK, Toure B, Coffie PA, Effi B, et al. Cervical cancer screening by visual inspection in Cote d'Ivoire, operational and clinical aspects according to HIV status. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitambo C, Khan S, Matanje-Mwagomba BL, Kachimanga C, Wroe E, Segula D, et al. Improving the Screening and Treatment of Hypertension in People Living with HIV. An Evidence Brief for Policy by Malawi's Knowledge Translation Platform. Malawi Med J. 2017;29(2):224–228. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v29i2.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Msyambosa KP, Phiri T, Sichali W, Kwenda W, Kachale F. Cervical cancer screening uptake and challenges in Malawi from 2011 to 2015: retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:806. doi: 10.11186/s12889-0163530_y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle EP, Murokora D, Perez C, Alvarez M, Quek SC, Campbell C. Treatment of cervical intraepithelial lesions. Int J of Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(Suppl 1):20–25. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kingham TP, Alatise OI, Vanderpuye V, Casper C, Abantanga FA, Kamara TB, et al. Treatment of cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):e158–e167. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maseko FC, Chirwa ML, Muula AS. Health systems challenges in cervical cancer prevention program in Malawi. Glob Health Action. 2015 doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.26282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malawi Ministry of Health, author. Clinical Management of HIV in adults and children. Lilongwe: Ministry of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaff C, Singano V, Akello H, Amberbir A, Garone D, Berman J, et al. Early experiences of integrating non-communicable disease screening and treatment in a large ART clinic in Zomba Malawi. Durban, South Africa: 2016. Jul 18–22, Poster presented at: XXI International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell C, Kafwafwa S, Brown H, Walker G, Madetsa B, Deeny M, et al. Use of thermo-coagulation as an alternative treatment modality in a ‘screen-and-treat’ programme of cervical screening in rural Malawi. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:908–915. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro W, Gage J, Gaffikin L, Ferreccio C, Sellors J, Sherris J, et al. Cervical cancer prevention issues In depth I. Effectiveness safety and acceptability of cryotherapy: a systematic literature review. Alliance for cervical cancer prevention; 2003. [31 January 2018]. Available at http://www.path.org/publications/files/RH_cryo_white_ paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organisation, author. WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [31 January 2018]. Available at: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwi6pIOxn4LZAhXCShQKHQulAoAQFgglMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fapps.who.int%2Firis%2Fbitstream%2F10665%2F94830%2F1%2F9789241548694_eng.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3mjrq4rrUDWFxTwAYm-Tvo. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parham GP, Mwanahamuntu MH, Kapambwe S, Muwonge R, Bateman AC, Blevins M, et al. Population-Level Scale-Up of Cervical Cancer Prevention Services in a Low-Resource Setting: Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0122169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.012216927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parham GP, Mwanahamuntu MH, Sahasrabuddhe VK, Westfall A, King KE, Chibwesha C, et al. Implementation of cervical cancer prevention services for HIV infected women in Zambia: measuring program effectiveness. HIV Ther. 2010;4(6):703–722. doi: 10.2217/hiv.10.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.PATH, author. Treatment Technologies for Precancerous Cervical Lesions in Low-Resource Settings: Review and Evaluation. 2013. [31 January 2018]. [cited 2015 November 27]. Available at http://www. rho.org/HPV-screening-treatment.htm.

- 29.Singh P, Loke K, Hii JHC, Sabaratnam A, Lim-Tan SK, Sen DK, et al. Cold Coagulation Versus Cryotherapy for Treatment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: Results of a Prospective Randomized Trial. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 1988;4:211–221. doi: 10.1089/gyn.1988.4.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolman L, Sauvaget C, Muwonge R, Sankaranarayanan R. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of cold coagulation as a treatment method for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review. British J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:929–942. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]