Abstract

One of the most attractive commercial applications of semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs) is their use in lasers. Thanks to their high quantum yield, tunable optical properties, photostability, and wet-chemical processability, NCs have arisen as promising gain materials. Most of these applications, however, rely on incorporation of NCs in lasing cavities separately produced using sophisticated fabrication methods and often difficult to manipulate. Here, we present whispering gallery mode lasing in supraparticles (SPs) of self-assembled NCs. The SPs composed of NCs act as both lasing medium and cavity. Moreover, the synthesis of the SPs, based on an in-flow microfluidic device, allows precise control of the dimensions of the SPs, i.e. the size of the cavity, in the micrometer range with polydispersity as low as several percent. The SPs presented here show whispering gallery mode resonances with quality factors up to 320. Whispering gallery mode lasing is evidenced by a clear threshold behavior, coherent emission, and emission lifetime shortening due to the stimulation process.

Keywords: self-assembly, whispering gallery modes, supraparticles, semiconductor nanocrystals, lasing

Since the demonstration of amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) and optical gain in systems composed of colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs),1,2 these materials have gained tremendous interest due to their versatile optoelectronic properties and facile processing. In particular, the tunable photoluminescent (PL) emission and high quantum yield, excellent photostability, and nearly temperature-independent gain3 are the main features promoting NCs for lasing applications. NCs of different composition (e.g., CdSe/CdS, perovskites) and geometries (e.g., nanoplatelets, dot-in-rods) have therefore been thoroughly investigated as gain material for lasers during recent years.4−11 A major challenge hereby is the nonradiative exciton recombination by the Auger effect. Only recently, suppressed Auger recombination12 and the first NC lasers with continuous wave excitation and “nearly zero” lasing thresholds (β ≈ 1) through electrical pumping have been reported.13−15

In the quest to realize efficient NCs-based lasers, NCs have been implemented in a large variety of systems and cavities. Today, most optical cavities are realized as distributed Bragg reflectors, distributed feedback lasers, or even as waveguide-coupled ring resonators.16,17 The combination of NC size control with a high-quality cavity generally requires sophisticated and expensive fabrication methods. Importantly, NC lasing has also been achieved with geometries that are much easier to fabricate, e.g., by simple drying of films of the NCs which, under the conditions for which the coffee stain effects are prevented, can be dried as smooth and thin films.18 However, these systems are operating in the random-lasing regime, which lacks essential control over a huge number of lasing modes.8,19−21

Ordered spherical assemblies of NCs, also known as supraparticles (SPs),22,23 have recently gained interest due to their collective properties which differ from those of the composing NCs and through insights obtained on self-assembly in spherical confinement.22,24,25 For example, recently fabricated SPs can emit pure colors or can be tailored to allow tunable light emission (e.g., white light).26 SPs themselves can be made through self-assembly (SA) inside the spherical confinement induced by slowly drying of oil-in-water emulsion droplets. By controlling the emulsification procedure, SPs can be tuned with a specific diameter between 100 and 15000 nm.22,27−29 Furthermore, SPs can be made to be water or oil dispersible and can be realized as stable dispersions themselves, which strongly facilitates further processing or application of these systems. Additionally, it has been shown that the high effective refractive index that is realizable with SPs made from semiconductor NCs can lead to shape-dependent modulation of their photoluminescence emission (PL) originating from whispering gallery modes (WGMs),30 thus in principle, allowing the optical feedback necessary for obtaining lasing. Even though WGMs were observed in SPs, amplified spontaneous emission (ASE), optical gain, or lasing has not been demonstrated for these systems up to now.

Here, we report on optically pumped (pulsed laser with pulse duration of a few picoseconds; see the SI for further details) whispering gallery mode (WGM) lasing from self-assembled SPs composed of luminescent CdSe/CdS NCs, where the SPs act as both lasing cavity and gain medium. For very low excitation densities (<58 μJ/cm2), we observe resonance peaks superimposed on the PL emission of the SPs, associated with WGMs with a quality factor of about 320. When the excitation exceeds a certain threshold (58 μJ/cm2), we observe a discrete lasing peak and an effective 20-fold decrease in line width, superimposed on the WGMs, evolving into a multimode regime for higher pump pulse fluence. WGM-based lasing is supported by coherence measurements, showing spatial coherence over the entire rim of the SPs for a duration comparable to the pump pulse duration, and by a shortening of the exciton lifetime of almost 3 orders of magnitude.

Results

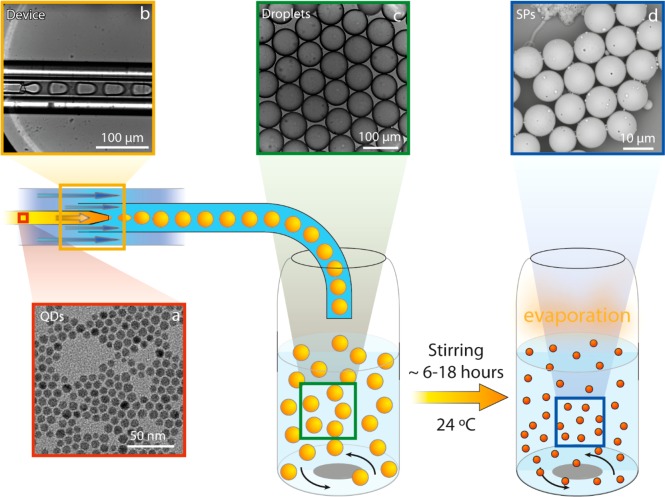

The synthesis of the SPs is schematically presented in Figure 1. The building blocks composing the SPs are CdSe/CdS NCs. They have an average diameter of 8.6 ± 1.0 nm (average diameter ± standard deviation, as determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM)), being composed of a 3.6 nm diameter CdSe core and 2.5 nm thick CdS shell (Figure 1a) (see the SI for further details). Twice the distance of the interpenetrating layer of ligands adds 3.8 nm to the interparticle spacing in our close-packed systems and, because of the monodispersity of the ligand molecules, reduces the total polydispersity of the particles to about 8%. A dispersion of these NCs (volume fraction 0.06%) is used to produce SPs through self-assembly enabled by evaporation of the apolar phase of an oil-in-water emulsion (see the SI for further details).22 Nearly monodisperse (<5%) droplets of NCs solution (oil phase) were formed using an in-flow custom-made microfluidic chip (Figure S6), which allows precise control of the shear forces and of the relative fluxes of the oil and water phases (Figure 1b,c and Figure S7), thus pinching off droplets of a certain size.31 After a certain amount of time (∼6–18 h), which is directly related to the droplet size and many other factors influencing the flux of oil through the system, the oil phase dissolves and finally evaporates out of the water, thus confining the NCs in smaller volumes inducing self-assembly and, once all oil has gone, creates solid SPs (Figure 1d). The size of the SPs can be precisely tuned between 5 and 15 μm by controlling the size of the droplets and the initial volume fraction of NCs in the oil phase (Figure S7). The SPs used in this experiment have an average diameter of 10.2 ± 0.5 μm, with a low polydispersity (PD < 5%), and present a smooth spherical shape, as inferred from SEM pictures (Figure 1d and Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Synthesis procedure based on an oil-in-water emulsion method. Cyclohexane droplets containing QDs (a) nearly monodisperse (polydispersity <5%) (yellow) are made in a microfluidic device (b) through the application of shear force exerted by the continuous flow of water (blue). The droplets (c) are then stirred in a vial at room temperature for 6–18 h to allow complete evaporation of the cyclohexane. In the end, we obtain monodisperse SPs dispersed in water (d). The insets show transmission electron microscopy image of NCs (a), optical microscopy images of the device (b) and droplets (c), and scanning electron microscopy image of SPs (d).

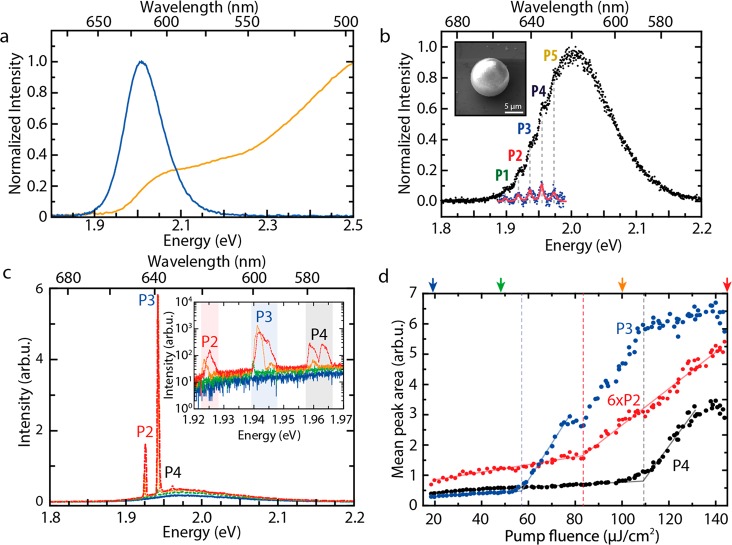

In Figure 2a, absorption and emission spectra of CdSe/CdS NCs (Figure 1a) are shown. The photoluminescence (PL) emission is centered at 2.015 eV (615 nm) with a full-width at half-maximum (fwhm) of 105 meV. The absorption exhibits the lowest excitonic transition at 2.087 eV (594 nm). The PL emission of a single SP under continuous wave excitation (CW) is shown in Figure 2. The PL emission of the SPs dispersion is centered at 2.003 eV (619 nm) with an fwhm of 102 meV. We observe a small general red shift (12 meV) of the emission spectrum of the NCs self-assembled in the SPs (Figure 2b inset) compared to the NCs freely dispersed in solution. Furthermore, the SPs show whispering gallery mode (WGM) resonance peaks on the low energy side of the emission peak (Figure 2b). This phenomenon, previously described in the literature for both acoustic waves32 and light waves,33−35 is based on the difference in refractive index between the material of the SPs (neff ∼ 1.7 for 2 eV and 27 °C; see the SI for details) and the environment (nair ∼ 1), which allows total internal reflection of the light inside the SP. The higher the index contrast, the smaller the SP can be without losing the light confinement. WGMs are formed when the optical path length of a round trip along the rim of the sphere is a multiple of the wavelength, and they can be observed as modulation of the PL emission spectrum.30 We attribute the absence of WGM resonance peaks on the high energy side and the small general red shift of the PL emission to reabsorption losses as a consequence of the small Stokes shift typical of semiconductor NCs (Figure 1b). The free spectral range (FSR) of the WGM,36 as obtained from the spacing between two successive maxima, is

where λ is the resonance center wavelength, L is the cavity length (L = 2πR for spherical cavities), and neff is the effective refractive index. This value is compatible with the radius R measured through SEM (R = 5 μm, Figures S1 and S2). Additionally, from the resonance peak width Δλ in the PL spectra, we are able to extract the quality factor Q = λ/Δλ of the cavity, which in our case is typically around 320 (Figure 2b). As numerical simulations using idealized spheres show much higher Q factors (see the SI), the measured value is probably lower due to surface roughness of the SP and/or other imperfections in their shape.

Figure 2.

(a) Absorption (yellow) and PL emission (blue) of the dispersed CdSe/CdS NCs. The PL peak maximum is centered at 2.015 eV with a fwhm of ∼105 meV and (b) PL emission of a single SP. The dashed gray lines indicate the position of WGM resonance peaks (numbered P1–5). The PL emission with removed background (blue) highlights these resonance peaks, which are then fitted with multiple Lorentzian peaks (red). (c) Emission from a single SP at different pump fluence (few ps pulse duration): 18 μJ/cm2 (blue), 48 μJ/cm2 (green), 100 μJ/cm2 (orange), and 145 μJ/cm2 (red) at low spectral resolution (300 lines/mm grating); (c inset) high spectral resolution (1800 lines/mm grating), revealing peak substructure (shaded regions denote areas used for analysis in b); (d) quantitative analysis of the P2–P4 mean peak areas (vertical dashed lines indicate the pump fluence at which new lasing peaks appear). The colored arrows above the graph indicate the pump fluence at which the respective spectra of panel (c) and (c inset) were taken.

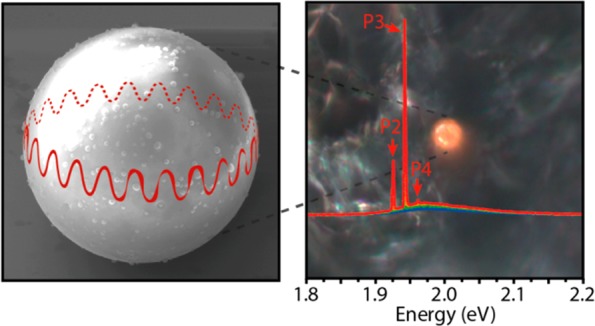

Figure 2c shows PL spectra of a single SP at different excitation fluences. Lasing is observed at the spectral positions of the WGM resonance peaks with thresholds as low as 58 μJ/cm2 (pulsed excitation; see the SI for further details). This threshold fluence corresponds to an average number of excitons per dots of ⟨N⟩ = 2.5 (using an absorption cross-section σ = 6 nm2),15 in agreement with previous observations for similar particles.17,37 The necessary modal gain at threshold can be estimated from the cavity Q factor by α = (2πneff/Q λ) = 520 cm–1, which is similar to typical values in literature for similar systems (∼650 cm–1, obtained from 980 cm–1 considering a filling factor of 66% for randomly packed spheres).16 The first lasing peak appears at 1.942 eV (P3 in Figure 2c), at the same spectral position as one of the modes observed in Figure 2b. This particular mode P3 is the first one to reach the lasing threshold as the effective gain of other modes is lower because of increasing reabsorption losses toward the blue side (P4) or lower material gain toward the red side (P2).

When the excitation fluence is increased, the intensity of the lasing peaks increases nonlinearly (Figure 2d), typical for optical gain conditions. Furthermore, additional lasing peaks are observed, indicating multimode behavior (from WGM modes that vary with their number of nodes of the electromagnetic field along the azimuthal and vertical directions within the SP; see Figure S5c,d) (Figure 2c). This phenomenon is particularly evident by monitoring the emission with a higher spectral resolution (Figure 2c inset), where peak substructure also becomes apparent. Multimode behavior is intrinsically associated with nearly spherical cavities and broadband emitters, as several almost energetically degenerate modes exist. For low excitation fluence, only the modes with the highest Q and material gain will be able to lase, while for higher fluence more modes will fulfill the conditions of modal gain necessary to reach the lasing regime.

By quantitatively examining the evolution of the PL emission as a function of pump fluence (Figure 2d), the threshold characteristics of the different laser modes can be extracted. We observe that the emission intensity starts increasing superlinearly at a pump fluence of ∼58 μJ/cm2, corresponding to the lasing threshold, and it keeps increasing with the same slope efficiency except for certain plateau regions. The main plateaus correspond to the appearance of new lasing modes of different longitudinal order that are competing for gain in the same spatial region (Figure 2c, P2–P4), thus indicating a multimode lasing regime with mode competition. We extracted the lasing threshold for different modes to be ∼83 μJ/cm2 for P2 and ∼110 μJ/cm2 for P4 (Figure 2d). For NCs with substantially thicker shells (CdSe/(Cd,Zn)S, five monolayers (ML) CdS, 1 ML CdZnS, 1 ML ZnS, for a total diameter of 11.4 ± 1.5 nm; see the SI for further details), WGM lasing can be observed from the blue side of the PL peak (due to lower absorption at the NC core) and the shell material (Figure S8).38 Concerning the peak width, we observe 20-fold decrease in line width above threshold: below the lasing threshold, P3 shows a line width of 10 meV, while it has a line width of 0.5 meV slightly above the threshold. Further above the threshold, the appearance of peak substructure due to onset of lasing from transversal modes (Figure 2c inset) increases the effective peak width again. We also note a slight general blue shift of the lasing peaks with increasing pump intensity, which is most likely due to the change of effective refractive index caused by bleaching39 or the plasma dispersion effect.40

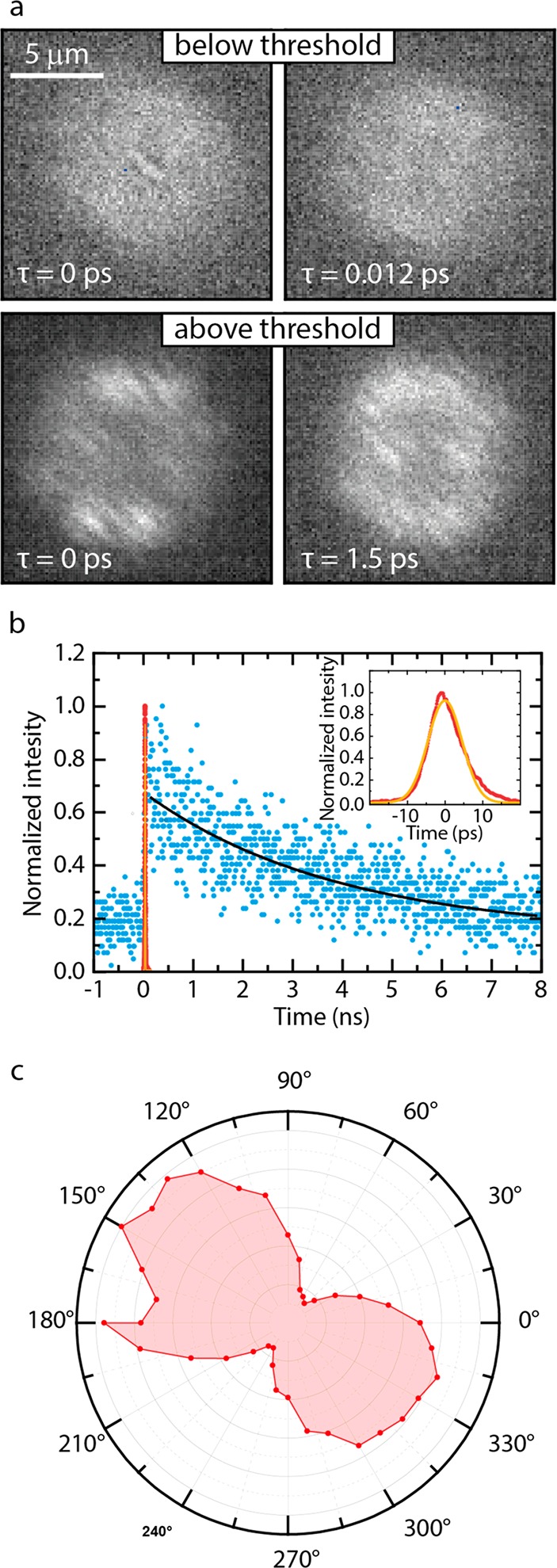

In Figure 3a, the temporal first-order coherence of the lasing regime is probed by a Michelson interferometer (see Figure S4 for details), where the image of the emission is split and recombined at different delay times between the two interferometer arms. The spatial coherence is obtained by spatially inverting the image in one of the arms before recombining the two beams. Below the lasing threshold, at ∼25 μJ/cm2, we observe only interference fringes from PL autocorrelation, lasting for few femtoseconds; i.e., no spatially or temporally extended coherence is found. Above the lasing threshold, at ∼100 μJ/cm2, we observe interference fringes extending over the whole outer rim of the SP and lasting for several picoseconds (approximately as long as the pump pulse duration). This temporal and spatial coherence indicates that (1) the SP is in the lasing regime and that the gain condition lasts, at least, for the pump pulse duration and (2) that the lasing we are observing is spatially coherent. In the images, the light emission is mainly localized at the rim of the SP, as expected for a WGM. The inhomogeneity along the circumference suggests that it is actually scattered from the SP by local defects as otherwise the wavevectors of WGM in perfectly smooth spheres would be tangential, and therefore, light leaking from the WGM could not be detected with our geometry where we image the SP from above. In addition to the well-defined free spectral range between the modes, this extended, ring-shaped spatial and temporal coherence crucially identifies the SPs as both cavity and gain media, excluding the appearance of random lasing in our NC assembly.19

Figure 3.

(a) Coherence measurements performed through a Michelson interferometer where the emission from the sample is split, spatially inverted, and delayed in one interferometer arm and then recombined on a camera. Below the lasing threshold (∼25 μJ/cm2, top row), only very short and localized coherence is observed, lasting for few femtoseconds. Above the lasing threshold (∼100 μJ/cm2, bottom row), the spatial coherence extends over the whole outer rim of the SP, lasting for several ps. (b) PL lifetime measurements of a single SP. The lifetime below the lasing threshold (in blue, and exponential fit with offset in black) is approximately 4 ns, while above the lasing threshold (in red, and Gaussian fit in orange) the lifetime shortens by almost 3 orders of magnitude, leading to a short emission pulse with fwhm of 10.7 ps. (c) Polarization measurement of the emission above lasing threshold. The dumbbell-shaped angular intensity dependence represents a dominantly linear polarization.

Furthermore, we performed time-dependent emission measurements to study the excitation fluence dependent dynamics in the two regimes (Figure 3b). In the low excitation regime below the lasing threshold (∼25 μJ/cm2), the SPs show an average PL lifetime of 4 ns, in agreement with a decay mainly governed by spontaneous emission. However, for higher excitation fluence above the lasing threshold (∼ 100 μJ/cm2), we observe a dramatic shortening of the emission lifetime by almost 3 orders of magnitude (fwhm of the emitted pulse is 10.7 ps) as a consequence of stimulated emission, further confirming lasing in the SPs. The spectral line width of 0.5 meV is about three times larger than the Fourier limit of 0.17 meV, suggesting that additional spectral broadening from multimode lasing or spectral chirping occurs.

Additionally, we investigated the polarization of the emission of single SPs (Figure 3c). Under lasing conditions, the emission shows a dumbbell angular dependency that indicates dominantly linear polarization. In principle, for a WGM propagating perfectly parallel to the substrate, unpolarized emission should be detected in a spatially integrating detector above the SP. The observed linear polarization, whose axis varies in orientation from SP to SP, could therefore arise from a tilted WGM propagation plane (as supported by FDTD simulations, see Figure S5). Another reason could be the inhomogeneity of scattering around the WGM circumference (see discussion above; the ring in Figure 3a is not continuous) that scatters the respective local polarization orientation into the detector. Hence, seemingly linear polarization could be an artifact from the difference in scattering intensities around the circumference of the SP.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we created an optically pumped WGM-based laser using self-assembled SPs composed of CdSe/CdS NCs, achieving thresholds as low as 58 μJ/cm2. In addition to drastic peak narrowing and nonlinear emission, lasing is confirmed by shortening of the exciton lifetime by 3 orders of magnitude and by spatially and temporally extended coherence. Our experiments demonstrate that high-quality optical microresonators can be fabricated through controlled self-assembly of colloidal NCs, where the superstructure acts as both laser resonator and gain medium, avoiding the need for a separate lasing cavity fabrication and NCs positioning inside it. Notably, the SPs preserve their properties over many weeks of experiments without showing any significant degradation or stability issues. The applicability of the SP synthesis to every shape of NC (i.e., nanoplatelets, nanorods41,42) and the excellent control over the SP size through microfluidics makes these structures versatile and potentially valuable for several applications. The SPs’ compatibility with water allows them to be used in microfluidics and biocompatible sensors. In fact, the sensitivity of WGM to the local environment could be exploited for sensors for biological43 or security applications.44 Such active microlasers provide significant sensitivity improvement over sensors that use passive WGM resonators due to the high nonlinearity and sensitivity to additional absorption near the threshold as well as amplification and line-narrowing associated with the laser process.

Methods

Chemicals

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, ≥ 98.5%), dextran from Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Mw 670000 g/mol), and cyclohexane (anhydrous, 99.5%) were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

Synthesis and Characterization of the SPs

The synthesis was performed in open air adapting a procedure from the literature.22 First, the CdSe/CdS solution of NCs in cyclohexane in a concentration of ∼1 mg/mL was prepared (volume fraction of ∼0.0006). Then a water solution made of 10 mL of milli-Q water containing 60 mg of SDS, the surfactant, and 0.4 g of dextran was prepared. The emulsification was performed using a custom-made microfluidic chip (see below for a more detailed description). For this experiment, we used flow rates of 1000 μL/h for the water phase and 200 μL/h for the NC dispersion, which produced droplets of 109 ± 4 μm of diameter (Figure S1a). The so-formed emulsion was collected in a vial containing water solution saturated with cyclohexane (to slow down the evaporation). The emulsion was then stirred at room temperature for 6–18 h (depending on the droplet size) in a cylindrical vial (height of 57.5 mm and diameter of 27.3 mm), which was covered on the top by a layer of parafilm pierced by several 0.8 mm holes to allow all of the cyclohexane to evaporate. Through the spherical confinement of the evaporating droplet, the NCs were pushed together to form the SPs. The so-formed SPs had a diameter of 10.2 ± 0.5 μm, which considering the initial volume fraction and the size of the droplets, is in agreement with our predictions of size, considering conservation of the mass of the NCs during the self-assembly. After the evaporation, the SPs were precipitated by centrifugation (3000 rpm for 20 min) and redispersed in milli-Q water. The SPs show a smooth surface and homogeneous internal distribution of the NCs (Figure S2). To prepare the samples for the experiment, the water solution of SPs was deposited on a silicon substrate, and then the water phase was evaporated to leave the SPs on the substrate. The same sample was used for the lasing measurements and for the SEM imaging.

Simulation

For simulations of the SPs optical behavior, we used a freely available FDTD software package (see the SI for further information).45

Optical Characterization

The PL emission of a single SP shown in Figure 2b was measured using a continuous wave (CW) excitation source at 405 nm wavelength with ∼2 μm beam diameter and collected through a 100× microscope objective with numerical aperture NA = 0.5. For all lasing measurements, we used a frequency-doubled regenerative amplifier seeded by a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser, resulting in laser pulses of 100–200 fs duration with a repetition rate of 1 kHz. This light was coupled to a 1 m long multimode optical fiber with 10 μm core diameter to achieve a beam which was more homogeneous than a Gaussian beam (it is more like a flat-top profile) and pulse stretching to several picoseconds pulse duration. An image of the beam profile and a cross section of the excitation beam on the sample are shown in Figure S3. The pump intensity was controlled with a movable gradient filter after the fiber. The excitation beam was focused with a long working distance apochromatic microscope objective (10 × , NA = 0.26) to a spot with fwhm = 10 μm on the sample. The SPs of ∼10 μm diameter fit completely into the flat-top region of the beam profile.

The emitted light from the SPs is collected through the same objective lens. Suitable long-pass filters are used to block the excitation light. The emission is detected by a fiber-coupled spectrograph (0.5 m focal length monochromator, 300 lines/mm, and 1800 lines/mm gratings) equipped with a liquid N2-cooled CCD (charge-coupled device) for the spectral measurements. The coherence measurements in Figure 3a were recorded using a Michelson interferometer (Figure S4). Here, the light from the sample is split with a nonpolarizing beam splitter cube, recombined, and focused after the Michelson interferometer on a cooled CCD, resulting in real-space interferograms. At the end of one interferometer arm, a hollow retroreflector is mounted on a motorized linear stage with an additional piezo actuator which inverts the image and provides an adjustable delay. The luminescence lifetimes shown in Figure 3b were recorded using a time-correlated single photon counting system with fiber-coupled avalanche photodiode (50 ps time resolution) for measurements below lasing threshold and a streak camera (2 ps time resolution) for measurements above the lasing threshold. The polarization in Figure 3c was probed using full rotation of a linear polarizer (extinction >10000:1) mounted on a motorized rotation stage directly after the collecting objective lens. The radial scale in the plot depicts the intensity and the angular angle of the polarizer.

Acknowledgments

L.C., P.G.M., and F.M. thank C. Kennedy for help with the microfluidics. This work was supported by the European Commission via the Marie-Sklodowska Curie action Phonsi (H2020-MSCA-ITN-642656), the Swiss State Secretariat for Education (SERI), and the NWO Graduate Program. D.V. acknowledges the ERC advanced grant 692691, First Step. A.v.B. and F.M. acknowledge partial financial support from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP-2007–2013)/ERC Advanced Grant Agreement 291667 HierarSACol.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07896.

CdSe/CdS NCs synthesis, microfluidics and droplet size control, WGM simulations, and calculation of the refractive index (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ F.M. and D.U. contributed equally to this work. L.C. and F.M. synthesized the NCs, and L.C., F.M., and P.G.M. prepared the SPs. F.M. and D.U. performed optical and electron microscopy of the SPs. D.U., F.M., and T.S. performed the optical measurements and the data analysis thereof. D.V., A.v.B., P.B., and R.F.M. supervised the project. A.v.B. initiated the research using SPs for lasing applications. All authors contributed to writing of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Klimov V. I.; Mikhailovsky A. A.; Xu S.; Malko A.; Hollingsworth J. A.; Leatherdale C. A.; Eisler H. J.; Bawendi M. G. Optical Gain and Stimulated Emission in Nanocrystal Quantum Dots. Science 2000, 290, 314–317. 10.1126/science.290.5490.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandyshev Y. V.; Dneprovskii V. S.; Klimov V. I.; Okorokov D. K. Lasing on Transition between Quantum-Well Levels in a Quantum Dot. Jetp Lett. 1991, 54, 442. [Google Scholar]

- Moreels I.; Rainò G.; Gomes R.; Hens Z.; Stöferle T.; Mahrt R. F. Nearly Temperature-Independent Threshold for Amplified Spontaneous Emission in Colloidal CdSe/CdS Quantum Dot-in-Rods. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, OP231–OP235. 10.1002/adma.201202067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim J. Q.; Christodoulou S.; Di Stasio F.; Krahne R.; Cingolani R.; Manna L.; Moreels I. Continuous-Wave Biexciton Lasing at Room Temperature Using Solution-Processed Quantum Wells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 891–895. 10.1038/nnano.2014.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio F.; Grim J. Q.; Lesnyak V.; Rastogi P.; Manna L.; Moreels I.; Krahne R. Single-Mode Lasing from Colloidal Water-Soluble CdSe/CdS Quantum Dot-in-Rods. Small 2015, 11, 1328–1334. 10.1002/smll.201402527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She C.; Fedin I.; Dolzhnikov D. S.; Dahlberg P. D.; Engel G. S.; Schaller R. D.; Talapin D. V. Red, Yellow, Green, and Blue Amplified Spontaneous Emission and Lasing Using Colloidal CdSe Nanoplatelets. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9475–9485. 10.1021/acsnano.5b02509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li X.; Song J.; Xiao L.; Zeng H.; Sun H. All-Inorganic Colloidal Perovskite Quantum Dots: A New Class of Lasing Materials with Favorable Characteristics. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7101–7108. 10.1002/adma.201503573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakunin S.; Protesescu L.; Krieg F.; Bodnarchuk M. I.; Nedelcu G.; Humer M.; De Luca G.; Fiebig M.; Heiss W.; Kovalenko M. V. Low-Threshold Amplified Spontaneous Emission and Lasing from Colloidal Nanocrystals of Caesium Lead Halide Perovskites. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–8. 10.1038/ncomms9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Su R.; Liu X.; Xing J.; Sum T. C.; Xiong Q. High-Quality Whispering-Gallery-Mode Lasing from Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanoplatelets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6238–6245. 10.1002/adfm.201601690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su R.; Diederichs C.; Wang J.; Liew T. C. H.; Zhao J.; Liu S.; Xu W.; Chen Z.; Xiong Q. Room-Temperature Polariton Lasing in All-Inorganic Perovskite Nanoplatelets. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 3982–3988. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazes M.; Lewis D. Y.; Ebenstein Y.; Mokari T.; Banin U. Lasing from Semiconductor Quantum Rods in a Cylindrical Microcavity. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 317–321. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Santamaría F.; Chen Y.; Vela J.; Schaller R. D.; Hollingsworth J. a; Klimov V. Suppressed Auger Recombination in “Giant” Nanocrystals Boosts Optical Gain Performance. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 3482–3488. 10.1021/nl901681d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K.; Park Y.; Lim J.; Klimov V. I. Towards Zero-Threshold Optical Gain Using Charged Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 1140–1147. 10.1038/nnano.2017.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J.; Park Y.-S.; Klimov V. I. Optical Gain in Colloidal Quantum Dots Achieved with Direct-Current Electrical Pumping. Nat. Mater. 2017, 17, 42–49. 10.1038/nmat5011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F.; Voznyy O.; Sabatini R. P.; Bicanic K. T.; Adachi M. M.; McBride J. R.; Reid K. R.; Park Y.-S.; Li X.; Jain A.; Quintero-Bermudez R.; Saravanapavanantham M.; Liu M.; Korkusinski M.; Hawrylak P.; Klimov V. I.; Rosenthal S. J.; Hoogland S.; Sargent E. H. Continuous-Wave Lasing in Colloidal Quantum Dot Solids Enabled by Facet-Selective Epitaxy. Nature 2017, 544, 75–79. 10.1038/nature21424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W.; Stöferle T.; Rainò G.; Aubert T.; Bisschop S.; Zhu Y.; Mahrt R. F.; Geiregat P.; Brainis E.; Hens Z.; van Thourhout D. On-Chip Integrated Quantum-Dot–Silicon-Nitride Microdisk Lasers. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 2–7. 10.1002/adma.201604866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivas C.; Li C.; Andreakou P.; Wang P.; Ding M.; Brambilla G.; Manna L.; Lagoudakis P. Single-Mode Tunable Laser Emission in the Single-Exciton Regime from Colloidal Nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavelani-Rossi M.; Lupo M. G.; Krahne R.; Manna L.; Lanzani G. Lasing in Self-Assembled Microcavities of CdSe/CdS Core/Shell Colloidal Quantum Rods. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 931. 10.1039/b9nr00434c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollner C.; Ziegler J.; Protesescu L.; Dirin D. N.; Lechner R. T.; Fritz-Popovski G.; Sytnyk M.; Yakunin S.; Rotter S.; Yousefi Amin A. A.; Vidal C.; Hrelescu C.; Klar T. A.; Kovalenko M. V.; Heiss W. Random Lasing with Systematic Threshold Behavior in Films of CdSe/CdS Core/Thick-Shell Colloidal Quantum Dots. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9792–9801. 10.1021/acsnano.5b02739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio F.; Polovitsyn A.; Angeloni I.; Moreels I.; Krahne R. Broadband Amplified Spontaneous Emission and Random Lasing from Wurtzite CdSe/CdS “Giant-Shell” Nanocrystals. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 2083–2088. 10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zavelani-Rossi M.; Krahne R.; Della Valle G.; Longhi S.; Franchini I. R.; Girardo S.; Scotognella F.; Pisignano D.; Manna L.; Lanzani G.; Tassone F. Self-Assembled CdSe/CdS Nanorod Micro-Lasers Fabricated from Solution by Capillary Jet Deposition. Laser Photon. Rev. 2012, 6, 678–683. 10.1002/lpor.201200010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Nijs B.; Dussi S.; Smallenburg F.; Meeldijk J. D.; Groenendijk D. J.; Filion L.; Imhof A.; Dijkstra M.; van Blaaderen A. Entropy-Driven Formation of Large Icosahedral Colloidal Clusters by Spherical Confinement. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 56–60. 10.1038/nmat4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanarella F.; Geuchies J. J.; Dasgupta T.; Prins P. T.; van Overbeek C.; Dattani R.; Baesjou P.; Dijkstra M.; Petukhov A. V.; van Blaaderen A.; Vanmaekelbergh D. Crystallization of Nanocrystals in Spherical Confinement Probed by In-Situ X-Ray Scattering. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 3675–3681. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Hermes M.; Kotni R.; Wu Y.; Tasios N.; Liu Y.; de Nijs B.; van der Wee E. B.; Murray C. B.; Dijkstra M.; van Blaaderen A. Interplay between Spherical Confinement and Particle Shape on the Self-Assembly of Rounded Cubes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2228. 10.1038/s41467-018-04644-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainò G.; Becker M. A.; Bodnarchuk M. I.; Mahrt R. F.; Kovalenko M. V.; Stöferle T. Superfluorescence from Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dot Superlattices. Nature 2018, 563, 671–675. 10.1038/s41586-018-0683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanarella F.; Altantzis T.; Zanaga D.; Rabouw F. T.; Bals S.; Baesjou P.; Vanmaekelbergh D.; van Blaaderen A. Composite Supraparticles with Tunable Light Emission. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9136–9142. 10.1021/acsnano.7b03975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintzheimer S.; Granath T.; Oppmann M.; Thai T.; Kraus T.; Vogel N.; Mandel K. Supraparticles: Functionality from Uniform Structural Motifs. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5093–5120. 10.1021/acsnano.8b00873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer C.; Fischer P.; Windhab E. J. Drop Formation in a Co-Flowing Ambient Fluid. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 3045–3058. 10.1016/j.ces.2004.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baroud C. N.; Gallaire F.; Dangla R. Dynamics of Microfluidic Droplets. Lab Chip 2010, 10, 2032. 10.1039/c001191f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanmaekelbergh D.; van Vugt L. K.; Bakker H.; Rabouw F. T.; de Nijs B.; van Dijk-Moes R.; Beasjou P.; van Blaaderen A. Shape-Dependent Multiexciton Emission and Whispering Gallery Modes in Supraparticles of CdSe/Multishell Quantum Dots. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 3942–3950. 10.1021/nn507310f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C.-H.; Weitz D. A.; Lee C.-S. One Step Formation of Controllable Complex Emulsions: From Functional Particles to Simultaneous Encapsulation of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Agents into Desired Position. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2536–2541. 10.1002/adma.201204657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt J. W.The Theory of Sound; Cambridge University Press, 1878; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mie G. Beiträge Zur Optik Trüber Medien, Speziell Kolloidaler Metallösungen. Ann. Phys. 1908, 330, 377–445. 10.1002/andp.19083300302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debye P. Der Lichtdruck Auf Kugeln von Beliebigem Material. Ann. Phys. 1909, 335, 57–136. 10.1002/andp.19093351103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasera A.; Dumeige Y.; Féron P.; Ferrari M.; Jestin Y.; Conti G. N.; Pelli S.; Soria S.; Righini G. C. Spherical Whispering-Gallery-Mode Microresonators. Laser Photonics Rev. 2010, 4, 457–482. 10.1002/lpor.200910016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabus D. G.Integrated Ring Resonators: The Compendium; Springer, 2007; Vol. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Smyder J. A.; Amori A. R.; Odoi M. Y.; Stern H. A.; Peterson J. J.; Krauss T. D. The Influence of Continuous vs. Pulsed Laser Excitation on Single Quantum Dot Photophysics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 25723–25728. 10.1039/C4CP01395F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Feber B.; Prins F.; De Leo E.; Rabouw F. T.; Norris D. J. Colloidal-Quantum-Dot Ring Lasers with Active Color Control. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 1028–1034. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimov V. I.; Schwarz C. J.; McBranch D. W.; Leatherdale C. A.; Bawendi M. G. Ultrafast Dynamics of Inter- and Intraband Transitions in Semiconductor Nanocrystals: Implications for Quantum-Dot Lasers. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1999, 60, R2177–R2180. 10.1103/PhysRevB.60.R2177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T.; Notomi M.; Kuramochi E.; Shinya A.; Taniyama H. Trapping and Delaying Photons for One Nanosecond in an Ultrasmall High-Q Photonic-Crystal Nanocavity. Nat. Photonics 2007, 1, 49. 10.1038/nphoton.2006.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Zhuang J.; Lynch J.; Chen O.; Wang Z.; Wang X.; LaMontagne D.; Wu H.; Wang Z.; Cao Y. C. Self-Assembled Colloidal Superparticles from Nanorods. Science 2012, 338, 358–363. 10.1126/science.1224221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besseling T. H.; Hermes M.; Kuijk A.; de Nijs B.; Deng T.-S.; Dijkstra M.; Imhof A.; van Blaaderen A. Determination of the Positions and Orientations of Concentrated Rod-like Colloids from 3D Microscopy Data. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 194109. 10.1088/0953-8984/27/19/194109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey A.-M.; McConnell G.; Guilhabert B.; Burley G. A.; Dawson M. D.; Laurand N. Organic Semiconductor Laser Biosensor: Design and Performance Discussion. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2016, 22, 6–14. 10.1109/JSTQE.2015.2448058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A.; Zhu Z.; Madigan C. F.; Swager T. M.; Bulović V. Sensitivity Gains in Chemosensing by Lasing Action in Organic Polymers. Nature 2005, 434, 876–879. 10.1038/nature03438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskooi A. F.; Roundy D.; Ibanescu M.; Bermel P.; Joannopoulos J. D.; Johnson S. G. Meep: A Flexible Free-Software Package for Electromagnetic Simulations by the FDTD Method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 687–702. 10.1016/j.cpc.2009.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.