Abstract

Background

The registration and certification of births has a wide array of individual and societal benefits. While near-universal in some parts of the world, birth registration is less common in many low- and middle-income countries, and the quality of vital statistics vary. We assembled publicly available birth registration records for as many countries as possible into a novel global birth registration database, and we present a systematic assessment of available data.

Methods

We obtained 4918 country-years of data from 145 countries covering the period 1948–2015. We compared these to existing estimates of total births to assess completeness of public data and adapted existing methods to evaluate the quality and timeliness of the data.

Results

Since 1980, approximately one billion births were registered and shared in public databases. Compared to estimates of fertility, this represents only 40.0% of total births in the peak year, 2011. Approximately 74 million births (53.1%) per year occur in countries whose systems do not systematically register them and release the aggregate records. Considering data quality, timeliness, and completeness in country-years where data are available, only about 12 million births per year (8.6%) occur in countries with high-performing registration systems.

Conclusions

This analysis highlights the gaps in available data. Our objective and low-cost approach to assessing the performance of birth registration systems can be helpful to monitor country progress, and to help national and international policymakers set targets for strengthening birth registration systems.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12963-018-0180-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Civil registration, Vital statistics, Birth certificates, Data quality

Background

The registration and certification of births, while a near-universal practice in some parts of the world, is far less common in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1]. Birth registration has a wide array of individual and societal benefits [2], including the identification and facilitation of legal entitlements [1], citizenship and voting rights [3], social security benefits, social inclusion [4], access to health and education services [5], security benefits in times of crisis [6], and proof of age [3]. So fundamental is birth registration to legal identity that it has frequently been described as a basic human right [7–9]. Additionally, reliable birth registration, compiled and consolidated within a national civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) system, should be the primary data source for fertility statistics [10]. Such data are necessary to track (often rapid) changes in fertility levels and patterns, to monitor and evaluate family planning programs, to provide the denominator for an array of key maternal and child mortality indicators [11], to project future population size and structure [12], and to inform planning for future health, education, and other social services. Their fundamental and comprehensive importance for a nation’s health and social development underlies calls for universal birth registration, as reflected in the Sustainable Development Goal 16.9 that aims, by 2030, to provide legal identity for all, including birth registration [13].

As interest in universal birth registration continues to grow, it will become increasingly important for countries and development partners alike to understand the performance of birth registration systems and in particular, to have some objective basis to determine whether these systems are ‘fit-for purpose’, as described above. Yet, despite their fundamental importance, the global status of birth registration is not well understood. While multiple studies have described, assessed, and monitored the global landscape of death registration [14–16], to our knowledge no comparable evaluations of birth registration systems exist. Some partial assessments to guide policy, however, have been undertaken. UNICEF, for example, has estimated that 71% of all children younger than 5 years have had their birth registered [17]. However, this estimate is based on self-reported survey responses that may be biased, especially as data from UNICEF show considerable discrepancies in some countries between reported birth registration and evidence of a birth certificate. For example, for only 10% of births in Rwanda that are reported to be “registered” can the family provide the birth certificate [18]. Moreover, the UNICEF approach does not include information on children who have died, especially neonatal deaths, for whom birth registration is often overlooked [10].

One reason why there has been no systematic assessment of birth registration data and systems could be the absence of a comprehensive and properly maintained and used global database. While agencies such as the World Health Organization annually aggregate and disseminate cause of death statistics based on death registration data from over 150 countries around the world, birth registration data are made public only through information provided by countries to the United Nations Statistical Division via an annual questionnaire, or through country-specific channels (e.g., national statistical offices) and other decentralized sources such as the Human Fertility Collection [19, 20].

To objectively assess the quality of birth registration data, and thus (indirectly) the performance of birth registration systems, it is first necessary to define the essential elements of data quality. While a fundamental measure of the quality of birth registration data is the completeness of registration, i.e., the percentage of all births that occur in a given year that are registered, there is other specific information about the newborn, the mother or the family that is, or should be, routinely collected for each birth and provided along with the birth certificate. Much of this information is likely to be of central importance for public health and demographic purposes, and hence reflects the utility of birth registration data. These characteristics include:

age of the mother, to understand the age patterns of fertility and to calculate the total fertility rate, the most common summary measure of fertility levels in a population;

sex of the newborn, to monitor the sex ratio at birth, also as an indicator of sex preferences in fertility [21];

birth order of the child, to understand fertility behavior (such as stopping behavior and progression patterns from one parity to the next); and

birthweight, given its critical role for the survival of the newborn [22].

An objective, reliable, and descriptive low-cost approach to assessing the performance of birth registration systems would enable countries to monitor progress in developing their birth registration and reporting systems, by facilitating international goal-setting, facilitating monitoring of development goals, and assisting in the global efforts to improve birth registration that are already underway by identifying specific aspects of data quality or availability that require attention [23]. This paper advances efforts to improve the monitoring of global birth registration in a number of ways. First, we present the results of what we believe is the first systematic effort to assemble publicly available birth registration records for as many countries as possible into a global birth registration database, similar to what WHO maintains for death registration and causes of death. Second, we present a systematic assessment of birth registration data quality around the world. We do so by adapting an existing framework used to assess the quality and utility of death registration statistics, known as the Vital Statistics Performance Index (VSPI) [15], to the context of birth registration. We expect that the birth registration database, and our findings and framework for assessing its utility, will help enable the measurement and tracking of performance metrics, especially between countries, and thus will be of immediate use by both countries and development partners to facilitate monitoring of progress with global and national development goals.

Methods

Data

We have systematically compiled a global database1 on birth registration statistics, based on 4918 country-years of data from 145 countries covering the period 1948–2015 (Table 1). For each country-year, the number of registered live births2 specified by age of mother, sex of newborn, birth order, and birthweight were compiled, where available. These variables are all recommended core topics to be collected for vital statistics purposes in national civil registration systems as specified in the UN Principles and Recommendations for a Vital Statistics System [21]. The primary source of data was the United Nations Statistical Division (UNSD) database, which provides birth registration data reported by countries in standardized tables in the Demographic Yearbook questionnaire [19, 24]. Because this database covers only a subset of countries likely to have functional birth registration systems, additional data were collected from Eurostat and directly from national statistical offices and ministry of health databases (Table 1). It is important to note that these are the data that are publicly available. Most, if not all, countries are likely to have some form of a birth registration system, but in many countries these data are not published. For example, there are many countries reported by UNICEF as having birth registration data as reported in surveys, but which cannot be found in the UNSD database or country statistical office publications [18].

Table 1.

Data availability

| Region | Country | Years with dataa |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Albania | 1948, 1950–1967, 1969–1971, 1979–2013 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Algeria | 1964–1965, 1978–1980, 1985–1986 |

| East Asia/Pacific | American Samoa | 1952–1969, 1971–1973, 1976, 1982, 1984–2014 |

| High Income | Andorra | 2002–2012 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Antigua and Barbuda | 1972–1975, 1977–1986, 1993, 1995 |

| High Income | Argentina | 1960–1966, 1968–1970, 1979–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Armenia | 1982–1994, 1996–2000, 2002–2004, 2006–2009, 2014 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Aruba | 1993–1995, 1997–2015 |

| High Income | Australia | 1948–2014, 2010–2015 [32] |

| High Income | Austria | 1951–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Azerbaijan | 1982–2004, 2006–2010, 2012–2014 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Bahamas | 1968–1977, 1990–1992, 1996 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Bahrain | 1977–2014 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Barbados | 1954–1980, 1982–1987, 1990–1991, 2005–2007 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Belarus | 1969–1973, 1986–1999, 2002–2014 |

| High Income | Belgium | 1947–1970, 1972–1983, 1986–1987, 1989–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Bermuda | 1962–1965, 1975–1989, 2006–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1989–1991, 1996–2010, 2012 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Brazil | 1994–1999, 2000–2015 [33] |

| High Income | Brunei Darussalam | 1969–1974, 1976, 1978, 1981–1992, 1996–2002, 2006–2008, 2011–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Bulgaria | 1949–1990, 1992–2014 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Cabo Verde | 1979–1985, 1990 |

| High Income | Canada | 1948–2009, 2010–2014 [34] |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Cayman Islands | 1981–1983, 1986–1995, 2009, 2011–2014 |

| High Income | Chile | 1948–2003, 2005–2014, 1997–1999, 2005–2014 [35] |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Colombia | 1998–2014 [36] |

| East Asia/Pacific | Cook Islands | 1971–1977, 1979–1982 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Costa Rica | 1953–1974, 1976–1991, 1994–1997, 1999–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Croatia | 1988–2014 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Cuba | 1965–1971, 1976–1989, 1991, 1993–2014 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Curaçao | 2009–2015 |

| High Income | Cyprus | 1948–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Czech Republic | 1991–2014 |

| High Income | Denmark | 1948–1966, 1968–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Dominica | 1960, 1966, 1969, 1985–1989, 2005–2006 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Ecuador | 1992–2007, 2009–2010 [37] |

| North Africa/Middle East | Egypt | 1965–1999, 2006–2012 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | El Salvador | 1948–2004, 2005–2007, 2010, 2012 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Estonia | 1986–2015 |

| High Income | Faeroe Islands | 1951–1966, 1968–1987, 1989, 2005–2007 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Fiji | 1948–1987, 2004, 2008 |

| High Income | Finland | 1948–2015 |

| High Income | France | 1948–1972, 1974–2009, 2011–2014, 2015 [38] |

| Latin America/Caribbean | French Guiana | 1951–1970, 1972–1976, 1984–1985, 1996, 1998–2003, 2005–2007 |

| East Asia/Pacific | French Polynesia | 1968 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Georgia | 1989, 1992, 1994–1997, 1999–2015 |

| High Income | Germany | 1991–1997, 1999–2015 |

| High Income | Greece | 1956–1985, 1990–2015 |

| High Income | Greenland | 1952–1965, 1967–1986 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Grenada | 1951–1969, 1978, 1997, 2000 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Guadeloupe | 1950–1967, 1969–1970, 1975, 1978–1980, 1984–1986, 1991, 1999–2003 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Guam | 1949–1986, 1988–1992, 1999, 2001–2004, 2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Guatemala | 1948–1973, 1975–1979, 1981–1999, 2006, 2009–2014 [39] |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Guyana | 1954–1956, 1960–1961, 1967–1972, |

| East Asia/Pacific | Hong Kong | 1969–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Hungary | 1948–2015 |

| High Income | Iceland | 1948–2015 |

| South Asia | India | 2011–2015 [40] |

| North Africa/Middle East | Iran | 2011–2013 |

| High Income | Ireland | 1955–2015 |

| High Income | Isle of Man | 1955–1961 |

| High Income | Israel | 1953–2015 |

| High Income | Italy | 1948–1964, 1973, 1980–1997, 1999–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Jamaica | 1948–1964, 1977–1984, 1986–1989,1995–1996, 2000–2004, 2016 |

| High Income | Japan | 1948–2010, 2012–2014, 2011, 2015 [41] |

| North Africa/Middle East | Jordan | 1969–1979, 2000–2015 [42] |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Kazakhstan | 1987–2008, 2012–2013 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Kosovo | 2002–2003, 2005, 2008, 2011 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Kuwait | 1963–1970, 1972, 1987, 1991–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Kyrgyzstan | 1980, 1982–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Latvia | 1986–2015 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Libya | 1972–1977, 1981, 1996, 2000, 2002 |

| High Income | Liechtenstein | 1965–1966, 1968, 1978–1983, 1986, 1987, 1993, 2003–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Lithuania | 1970–1977, 1985–2015 |

| High Income | Luxembourg | 1948–2014, 2015 [38] |

| East Asia/Pacific | Macao | 1955–2015 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Malaysia | 1990–1997, 2001–2009, 2011–2015 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Maldives | 1996, 1999–2014 |

| Sub–Saharan Africa | Mali | 1897 |

| High Income | Malta | 1957–1990, 1992–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Martinique | 1950–1970, 1972–1976, 1984–1992, 1999–2003, 2005–2007 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Mauritius | 1990–2003, 2005–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Mexico | 1985–2015 [43] |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Moldova | 1987–1992, 1995–1996, 1998–2014 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Mongolia | 1980, 1990, 1994–2010, 2012–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Montenegro | 1980, 1990, 2000, 2003–2009 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Montserrat | 1982–1986, 1994–1999, 2010–2014 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Morocco | 1990–1991, 1993, 1995–2001 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Nauru | 1965–1968, 2009–2011 |

| High Income | Netherlands | 1948–2014, 2015 [38] |

| East Asia/Pacific | New Caledonia | 1962–1968, 1970–1985, 1987, 1990–1994, 1996–2003, 2005–2007, 2010, 2012 |

| High Income | New Zealand | 1962–2015 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Niue | 1957–1962, 2009 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Norfolk Island | 1948–1972, 1974–1976, 1978–1981, 1983–1984, 1988, |

| High Income | Norway | 1948–2014, 2015 [38] |

| North Africa/Middle East | Oman | 2006–2015 [44] |

| East Asia/Pacific | Palau | 1989–2005 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Panama | 1950, 1952–2000, 2002–2003, 2005–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Peru | 2013–2015 [45] |

| East Asia/Pacific | Philippines | 1990–1993, 1997–2007, 2009–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Poland | 1950–2015 |

| High Income | Portugal | 1948–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Puerto Rico | 1948–1962, 1964–1985, 1987–1994, 1996–2000, 2002–2009, 2012–2015 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Qatar | 1985–1994, 1996–2010, 2012–2013 |

| High Income | South Korea | 1993–2014 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Reunion | 1950–1970, 1980, 1982–1986, 1989, 1993–1997, 2002–2003, 2005–2007 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Romania | 1955, 1957–2014, 2015 [38] |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Russia | 1960,1965, 1970, 1975, 1980–1989, 1991–2004, 2006–2011, 2013, 2014 [38] |

| High Income | Saint Pierre and Miquelon | 1948–1952, 1959, 1963–1964, 1967, 1969, 1973–1977 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 1952–1956, 1960–1964, 1977–1984, 1986, 1988, 1992–1994, 1996–2005, 2008–2009, 2013–2014 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Saint Kitts and Nevis | 1956–1972, 1974–1991, 1993–1996 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | St Lucia | 1953–1961, 1963, 1975, 1978–1986, 1994–2002, 2004–2005 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Samoa | 1993 |

| High Income | San Marino | 1960–1989, 1992–1995, 1997–2004, 2011–2014 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Sao Tome and Principe | 1958, 1974–1979 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Serbia | 2000–2015 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Seychelles | 1982,1984–1985, 1990, 1992–1993, 1995–1996, 2004–2015 |

| High Income | Singapore | 1948–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Slovakia | 1988–1995, 1997–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Slovenia | 1987–2015 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | South Africa | 1998–2015 [46] |

| High Income | Spain | 1948–1983, 1985–2014, 2015 [38] |

| East Asia/Pacific | Sri Lanka | 1952–1969, 1977–1989, 1991, 1995–1996, 2001, 2006–2010 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Suriname | 1980–1986, 1988–2007, 2012–2014 |

| High Income | Sweden | 1948–2014, 2015 [38] |

| High Income | Switzerland | 1948–1982, 1984–2014, 2015 [38] |

| East Asia/Pacific | Taiwan | 1982–2014 [47] |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Tajikistan | 1989–1994, 2001–2003 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | TFYR of Macedonia | 1989–2015 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Thailand | 1991–1992, 1994, 1997 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Tonga | 1990, 1993–2000, 2002–2003 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Trinidad and Tobago | 1992–1995, 1997, 2002, 2004–2006, 2008–2009 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Tunisia | 1960, 1965–1972, 1974, 1977–1980, 1985–1989, 1992–1995, 1998, 2006–2007, 2011 |

| North Africa/Middle East | Turkey | 2009–2015 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Turkmenistan | 1989 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Turks and Caicos Islands | 2001–2005 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Ukraine | 1969–1971, 1973–1975, 1987–1996, 1998, 2001–2004, 2006–2008, 2010–2012, 2014–2015 |

| High Income | United Kingdom | 1982–2004, 2007–2014, 2015 [38] |

| High Income | United States | 1948–1989, 1991, 1993–2002, 2003–2015 [48] |

| Latin America/Caribbean | United States Virgin Islands | 1948–1962, 1964–1967, 1969–1972, 1977–1997 |

| High Income | Uruguay | 1949–1954, 1963, 1977–1989, 1993, 1996–1997, 1999–2007, 2012–2014 [49] |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Uzbekistan | 1989, 1993–1997, 1999–2000, 2005–2015 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Venezuela | 1990–1991, 1996, 1998–2002, 2005–2007, 2009–2015 |

| East Asia/Pacific | Wallis and Futuna Islands | 1969, 1996–2008 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | Yugoslavia | 1994–1995 |

aUnless otherwise specified with a citation, the source for data is [19] UN Statistics Division. UNSD Demographic Statistics [Internet]. United Nations; 2017. Available from: http://data.un.org

Assessment of completeness

In order to assess birth registration completeness, we relied on existing annual estimates of total births produced by the United Nations Population Division [25]. We use these estimates as a measure of the total number of live births that occur each year in a country, recognizing that they are subject to methodological and empirical uncertainty. They are, however, the only estimates of the total numbers of births occurring in countries currently available. The observed number of births reported for each country were divided by estimates of the total number of live born in each country-year.

The resulting figures thus represent a measure of completeness of birth registration data in the public domain. We assume that in a country-year which has made birth registration data available, the data include all registered births for that year, and therefore can be used to assess registration completeness. In country-years where no data are available, we are unable to draw conclusions about registration completeness.

Vital statistics performance index

To evaluate the utility of vital statistics with respect to their accuracy in addition to their completeness and availability, we adapted methods defined by Phillips et al. 2014 [15]. In their study, six empirical indicators were used to create a summary index of death registration data utility known as the VSPI. Comparably, we defined four indicators of data quality: the proportion of registered births with unspecified maternal age, the proportion of registered births with unspecified newborn sex, the proportion of registered births with unspecified birthweight, and the proportion of registered births with unspecified live birth order. Following the VSPI framework, we included two additional components of system performance which, together with the four components of data quality mentioned above define a summary of the overall accuracy of birth registration data.

These indicators of performance were selected on the basis of their suitability for assessing the policy relevance of demographic and fertility statistics (as described above), their availability in many data systems, and their inclusion in global recommendations for vital registration systems [21]. In doing so, we implicitly assume that complete, accurate, and recent information about maternal age, newborn sex, birthweight, and live birth order are useful to describe about the distribution and trends of fertility, and can summarize the overall accuracy of data used to represent those fertility trends.

As detailed in Phillips et al. 2014 [15], simulation techniques were used to combine the six indicators into a composite index. The purpose of the simulation is to assess the distortion in observed fertility trends as compared to the true underlying trends associated with different levels of the above indicators. As an example, if a certain proportion of births are reported with an unknown sex, the simulation approach measures the accuracy of sex ratios in the observed data as compared to the sex ratio of the population from which the data were derived. Each other indicator’s accuracy was assessed using a separate, relevant objective function. Maternal age was evaluated using the fraction of births in each age group (less than 15 years of age, 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, and greater than or equal to 45 years of age). Birthweight was evaluated using the fraction of births in each birthweight category (less than 2500 g, 2500–3499, and greater than 3500 g). Birth order was evaluated using the proportion of births in each sibship size (0, 1, 2, or 3 or more livebirth siblings). Like the VSPI framework, we used the population-level accuracy formula defined by Murray et al. 2011 to assess the similarity between observed fractions and that of the underlying simulated population [26].

We used the above-mentioned estimates of birth counts as the population for the simulation [25]. Because these estimates are not disaggregated by sex, birthweight, and live birth order of the newborn, and because no other global estimates are as well, to our knowledge, we developed an approach to disaggregating them based on available data. We combined publicly-available survey data as direct measures of the fraction of births in each birth group (age, sex, birthweight, and birth order). These data included 211 Demographic and Health Surveys from 73 countries and the UK Understanding Society Longitudinal Household Study [27, 28]. We used regression techniques (see Additional file 1 for details) to estimate the fraction of births by birth group from the survey data. Modeled birth fractions were multiplied by the UN estimates of births by country, year, and maternal age to disaggregate them, leaving the total unchanged.

Using these estimates of birth counts as a population of simulated births, we drew a weighted sample of birth certificates in order to simulate progressively less-than-complete registration. Observed patterns of missing data from the birth registration database described above were used as empirical probabilities for weighted sampling. Finally, we computed observed proportions of missing data among the actual data, and simulation results were used to assess the accuracy of those observed proportions.

The separate indicators of data quality were then combined by taking the product of accuracy measures from the simulation. Following Phillips et al. 2014 [15], an exponential smoothing algorithm was applied to the product in order to measure the component of overall utility related to the timeliness of the data. Further details on the exact computation of the VSPI has been described elsewhere [15].

The result of this simulation and smoothing procedure is a single index of the policy utility of birth registration statistics for a given population in a given year, simultaneously capturing data availability, quality, completeness, and timeliness, which we will term VSPI-B. This index quantifies the extent to which registered and available birth data are accurate in reflecting the underlying demographic profile of births in the country.

Results

We analyzed 2680 country-years of data, from 109 countries spanning 1980 to 2015. We found 51 countries with greater than or equal to 30 years of available data since 1980, 75 countries with greater than or equal to 20 years of available data, and 11 countries with less than or equal to five years. Available data came from 32 high-income countries, 29 countries from Eastern Europe or Central Asia, 20 countries from Latin America and the Caribbean, 12 countries from North Africa and the Middle East, 11 countries from East Asia and the Pacific, and four countries from Sub-Saharan Africa (Table 1). Notably, several populous countries (e.g., China, Bangladesh and Pakistan) did not have any birth registration data publicly-available for analysis.

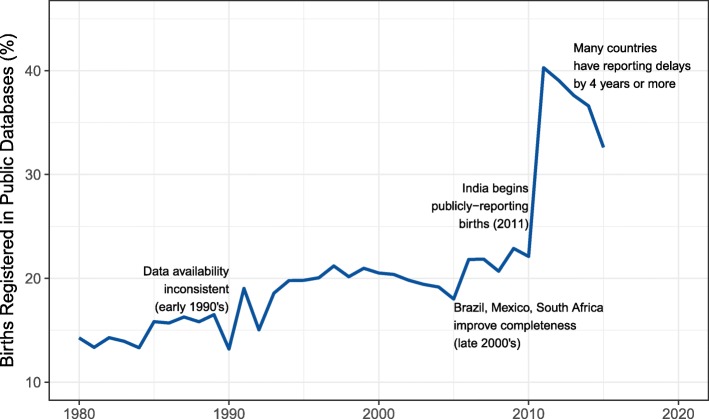

The data we were able to gather represented approximately 27.9 million births per year on average, ranging from 16.8 million births recorded in 1981 to 55.3 million births recorded in 2011, for a total of 1.01 billion births registered since 1980. The available data represented only 20.8% of the estimated total number of birth worldwide. This figure varied from 13.2% in 1990 to 40.0% in 2011, the most recent year for which data was available for most of the reporting countries. In 2015, the most recent year for which data were available, global availability was estimated as 32.6%. The most notable change in global registration completeness occurred in 2011, when India began publicly reporting data. Figure 1 displays the global percentage of births registered based on publicly-available data over time.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of global births registered in publicly-available data

Based on their most recent year with available data, 83 countries had estimated completeness greater than 90%, 19 countries had estimated completeness between 80 and 90%, five countries had estimated completeness between 50 and 80%, and two countries had estimated completeness below 50%. Completeness estimates for the most recent year for each country with available data are shown in Table 2. Additional file 2 displays the time series of completeness for each country.

Table 2.

Birth registration completeness in most recent year by country

| Country | Year | Completeness (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | 2013 | 90 |

| Algeria | 1986 | 90 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1995 | 97 |

| Argentina | 2014 | 100 |

| Armenia | 2014 | 100 |

| Australia | 2014 | 95 |

| Austria | 2015 | 100 |

| Azerbaijan | 2014 | 85 |

| Bahamas | 1996 | 100 |

| Bahrain | 2014 | 99 |

| Barbados | 2007 | 100 |

| Belarus | 2014 | 100 |

| Belgium | 2015 | 94 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2012 | 93 |

| Brazil | 2015 | 99 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 2014 | 100 |

| Bulgaria | 2014 | 100 |

| Canada | 2014 | 100 |

| Chile | 2014 | 100 |

| Colombia | 2014 | 90 |

| Costa Rica | 2014 | 100 |

| Croatia | 2014 | 95 |

| Cuba | 2014 | 100 |

| Cyprus | 2014 | 71 |

| Czech Republic | 2014 | 100 |

| Denmark | 2015 | 100 |

| Ecuador | 2010 | 88 |

| Egypt | 2012 | 100 |

| El Salvador | 2012 | 100 |

| Estonia | 2015 | 100 |

| Fiji | 2008 | 91 |

| Finland | 2015 | 98 |

| France | 2015 | 100 |

| Georgia | 2015 | 100 |

| Germany | 2015 | 100 |

| Greece | 2015 | 100 |

| Grenada | 2000 | 96 |

| Guatemala | 2014 | 88 |

| Hong Kong | 2014 | 81 |

| Hungary | 2015 | 100 |

| Iceland | 2015 | 97 |

| India | 2015 | 92 |

| Iran | 2013 | 100 |

| Ireland | 2015 | 91 |

| Israel | 2015 | 100 |

| Italy | 2015 | 100 |

| Jamaica | 2006 | 84 |

| Japan | 2015 | 99 |

| Jordan | 2015 | 93 |

| Kazakhstan | 2013 | 100 |

| Kuwait | 2014 | 80 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2015 | 94 |

| Latvia | 2015 | 100 |

| Libya | 2002 | 90 |

| Lithuania | 2015 | 100 |

| Luxembourg | 2015 | 96 |

| Macao | 2015 | 89 |

| Macedonia | 2015 | 97 |

| Malaysia | 2015 | 100 |

| Maldives | 2014 | 91 |

| Mali | 1987 | 95 |

| Malta | 2015 | 100 |

| Mauritius | 2015 | 95 |

| Mexico | 2015 | 87 |

| Moldova | 2014 | 89 |

| Mongolia | 2015 | 100 |

| Montenegro | 2009 | 100 |

| Morocco | 2001 | 89 |

| Netherlands | 2015 | 98 |

| New Zealand | 2015 | 100 |

| Norway | 2015 | 100 |

| Oman | 2015 | 85 |

| Panama | 2014 | 100 |

| Peru | 2015 | 85 |

| Philippines | 2015 | 74 |

| Poland | 2015 | 95 |

| Portugal | 2015 | 100 |

| Puerto Rico | 2015 | 73 |

| Qatar | 2013 | 93 |

| Romania | 2015 | 100 |

| Russia | 2014 | 99 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 2014 | 100 |

| Samoa | 1993 | 37 |

| Serbia | 2015 | 73 |

| Seychelles | 2015 | 97 |

| Singapore | 2015 | 83 |

| Slovakia | 2015 | 99 |

| Slovenia | 2015 | 92 |

| South Africa | 2015 | 83 |

| South Korea | 2014 | 93 |

| Spain | 2015 | 100 |

| Sri Lanka | 2010 | 100 |

| Suriname | 2014 | 100 |

| Sweden | 2015 | 97 |

| Switzerland | 2015 | 100 |

| Taiwan | 2014 | 100 |

| Tajikistan | 2003 | 49 |

| Thailand | 1997 | 95 |

| Tonga | 2003 | 97 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2009 | 89 |

| Tunisia | 2011 | 100 |

| Turkey | 2015 | 100 |

| Turkmenistan | 1989 | 96 |

| Ukraine | 2015 | 85 |

| United Kingdom | 2015 | 96 |

| United States | 2015 | 100 |

| Uruguay | 2014 | 100 |

| Uzbekistan | 2015 | 100 |

| Venezuela | 2015 | 100 |

Among the indicators of data quality, most country-years reported births by maternal age and the newborn’s sex (95.3 and 73.4% of country-years respectively), when data were available. Fewer countries reported births by live birth order and birthweight, with 55.6 and 51.1%, respectively, of country years containing these indicators. Among countries which did report each indicator, some missing values were observed as well. The indicator with the highest proportion missing was birth weight, with 2.6% of births with unknown birth weight. Maternal age and live birth order had fewer missing values: 1.0% each. Births without a recorded sex were very rare, occurring in only 0.05% of cases. Additional file 2 displays the level of each indicator over time by country.

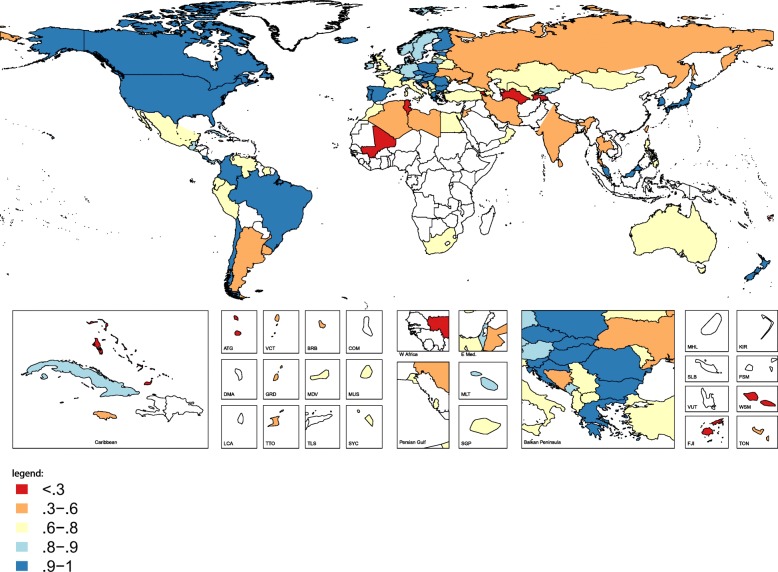

Combining completeness, quality, and timeliness, Fig. 2 displays the VSPI-B scores for each country for their most recent year with available data. 26 countries had VSPI-B scores in the highest category, between 0.9 and 1. These countries include many high- and middle-income countries with high completeness, and are generally countries which report births by all four data quality indicators. 17 countries had VSPI-B scores in the range 0.8–0.9. These countries also typically included mostly high- and middle-income countries, and were characterized by high completeness but sporadic reporting of the four data quality indicators. 38 countries were in the range 0.6–0.8. Spanning high-, middle-, and lower-middle income countries, these countries’ VSPI-B scores were driven by a mixture of lower completeness and lack of reporting of one or more data quality indicator. 19 countries had VSPI-B scores in the 0.3–0.6 range, characterized by either lower completeness, erratic availability of data, and/or lack of reporting on multiple data quality indicators (i.e., only reporting births by mother’s age or newborn’s sex, but not the others). Finally, nine countries had VSPI-B scores that were lower than 0.3. These countries typically had only few years with available data, low completeness, and/or lack of reporting of multiple indicators of data quality. Additional file 2 displays the time series of VSPI-B scores for each country.

Fig. 2.

Vital statistics performance index (most recent year with available data)

The results from the simulation indicate that, all else being equal, the completeness indicator has the highest weight in the VSPI-B. This is evidenced by Additional file 3, which displays the simulated accuracy associated with each indicator at varying levels among simulated samples. At high levels, all five indicators have generally similar accuracy (i.e., similar influence on the VSPI-B score), but at lower levels the indicators have quite different values. This is the result of different empirical simulation probabilities to inform the weighted samples.

Discussion

This paper presents, for the first time to our knowledge, a systematic assessment of the availability and quality of data reported by birth registration systems worldwide. As Mikkelsen et al. 2015 [16] argue, vital registration data quality can be assumed to be an accurate reflection of the performance of the registration system itself. In assessing birth registration data quality, we demonstrate each country’s progress toward strengthening birth registration through an adaptation of the Vital Statistics Performance Index. We also present estimates of the country-level completeness of birth registration based on available data. This assessment is based on the largest database of its kind, containing records of over one billion births since 1980 by country, year, maternal age, sex, birthweight, and live birth order.

Although over 100 countries had at least one data point, the availability of data remains low in many parts of the world. Our assessment of birth registration availability and completeness, where available, demonstrates that sharing of birth registration data is surprisingly low compared with death registration, although it does appear to be increasing. Only around 33% of births worldwide in 2015 were registered with the aggregate records made publicly available. This (and even the 2011 peak of 40% availability) is considerably less than for deaths, where 55–60% of global deaths are now registered in publicly available data systems. Further, we found considerable variance between birth reporting systems in that some countries report births by maternal age, sex, birthweight, and live birth order, while others exclude some or all of this information.

This description of birth registration completeness in country-years where it is possible to assess is in stark contrast to other assessments, particularly UNICEF’s State of the World’s Children report [17]. In their most recent such report, completeness estimates are much higher than those presented here, even in country-years with data available to assess. For example, the available data from the Philippines in 2015 represent only 74% of the estimated births according to our assessment, but the UNICEF report estimates 90% completeness. Notable examples of large discrepancies in other parts of the world include Peru (85% completeness according to 2015 data, as compared with 98% according to UNICEF), and Serbia (73% as compared to 99%). Other countries, such as South Africa, are closer, but still different (83% as compared to 85%). The reasons for the discrepancies are likely twofold. First, the alternative estimates of global birth registration completeness are based on self-report in surveys, not actual records of birth certificates. Issues of recall bias, survival bias, and survey instruments that do not confirm the actual existence of the birth certificates, are likely to lead to over-estimates of completeness via this method. Second, the estimates of completeness we present reflect the accuracy of the estimated denominator data as much as they do the completeness of systems. As already noted, the model estimates of total births include uncertainty intervals within which the total births may fall. While it would have been ideal to propagate that uncertainty into our estimates of completeness, uncertainty estimates were not available to do so at the time of analysis.

Altogether, these findings imply that approximately 74 million births (53.1% of annual global births) per year occur in countries whose systems do not systematically register them and release the records publicly. Conversely, only about 12 million births per year (8.6%) occur in countries with high-performing registration systems, i.e., those with consistent data availability, high completeness and reporting by maternal age, sex, birthweight and live birth order.

The assessment of birth registration is not without limitations however. Primarily, these numbers are based on available data only. This caution is especially salient in that it renders estimates of global registration completeness impossible, as noted above. There are likely more births registered per year that do not get aggregated and reported in order for us to assess them. As such, these availability numbers should be considered as the minimum completeness, and are most useful in countries where data are public. Evidence from China, for example, suggests that about 10 million births per year are registered in the country, which would increase global birth registration completeness to close to 50% were they to be made available for analyses such as that reported here. The assessment of completeness where data are available may also be limited by the assumption that all registered births are reported when a public release is made. The assessment of data quality is also limited to the data that are available. Many countries may have low VSPI-B scores not because their registration systems are functioning poorly, but because the data aren’t released. That includes missing years, but also failure to report certain variables. For example, it is rare to fail to record the sex of a child on their birth certificates, but many countries have not made such information publicly available. Without further data to inform our assessment, it is impossible to distinguish the reasons for lack of reporting. Additionally, some of the details of the VSPI-B simulations are subject to limitations. Principal among them is the fact that the simulations and estimates of disaggregated birth counts are based, in part, on Demographic and Health Surveys and the Understanding Society Survey. With more data, these estimates may have been more accurate. Finally, it could be argued there are other means of measuring the quality of birth registration data; for example, the percentage of births that are registered late or with unspecified type of site of occurrence (e.g., hospital, home etc.). However, given the largest available source of data, the UN database, did not collect these data, we were not able to include them in our analysis.

Conclusion

Our findings have a number of important implications and uses. First, we highlight the gaps in available data. While national policymakers may have unpublished data at their disposal, international and multinational health and development organizations are often reliant on public information of registered births, which we demonstrate are unavailable in many country-years. These findings underscore the significance of open data practices for public policy.

Second, we present an objective and low-cost approach to assess the performance of birth registration systems, wherever data are available. This can be helpful to monitor country progress and benchmark efforts to improve birth registration against national and international goals, especially in an era with significant multilateral, bilateral, and philanthropic investments in strengthening CRVS systems [23]. In addition, we present a set of metrics for completeness and overall system performance that is consistent between countries and over time. As such, these results may be useful for international goal-setting.

An important outcome of this work should be to highlight both the importance of birth registration as a source of fertility statistics and the limitations of the available data. National and subnational governments require routine and timely birth registration data for a range of purposes, not least of which is to lessen reliance on costly sample surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys that produce fertility statistics with considerable uncertainty in small areas and which can be 2–5 years out of date once available. More generally, the data generated by civil registration systems are of paramount importance to global health and development efforts, as well as for critical epidemiologic and demographic research [10, 16, 29]. Some authors have even argued that the heightened ability to design and implement effective health policy afforded by greater civil registration has led to a measurable relationship with population health outcomes [30, 31]. This will hopefully encourage stakeholders to collect, consolidate, use, and release more data, release data more promptly, and ensure they maintain a centralized, standardized system for aggregating birth registration data. Considering that birth registration is seen as a fundamental human right, and given the enormous policy relevance of timely, accurate, and complete information on fertility patterns, our findings should be taken as an urgent call for immediate, coordinated, and sustained support to countries to strengthen birth as well as death registration systems, and for greater global efforts to register births and incorporate the minimum demographic and health indicators associated with each of them.

Additional files

Further Statistical Details: Disaggregating Estimated Birth Counts by Sex, Birthweight and Live Birth Order. A two-page document describing the methods applied to estimate birth counts disaggregated by sex, birthweight and live birth order. (DOCX 16 kb)

VSPI-B Estimates and their Component Indicators by Country. A figure for every country with available data, displaying the observed data, final VSPI-B estimate, and sub-plots for each of the five components of the VSPI. (PDF 600 kb)

Simulated Age-Sex-Parity-Birthweight Fraction Accuracy Associated with Each Indicator. A figure displaying the results of the simulation procedure. The lines demonstrate the accuracy of simulated data in terms of the fraction of births in each birth group, as compared to the underlying population. Each line represents a different component of the VSPI-B at different simulated levels of that component. (PDF 7 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Rebecca Kippen of Monash University to initial discussions on the scope of the VSPI-B. The authors wish to thank Juan Cortez and Fatima Marinho from Ministry of Health Brazil for making available data from Brazil and Peru, and Caitlin Rawding of University of Melbourne for assisting with data collection and management.

Funding

This study was funded under an award from Bloomberg Philanthropies to the University of Melbourne to support the Data for Health Initiative. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this analysis can be downloaded from the following URL: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-birth-registration-database-1948-2015

Abbreviations

- CRVS

Civil registration and vital statistics

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- UNSD

United Nations Statistical Division

- VSPI

Vital Statistics Performance Index

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception of the study and drafting of the manuscript. DEP carried out the data analysis, TA carried out data collection and management. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Data file can be downloaded from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-birth-registration-database-1948-2015

The analysis is restricted to live births.

Contributor Information

David E. Phillips, Email: davidp6@uw.edu

Tim Adair, Email: timothy.adair@unimelb.edu.au.

Alan D. Lopez, Email: alan.lopez@unimelb.edu.au

References

- 1.Setel PW, Macfarlane SB, Szreter S, Mikkelsen L, Jha P, Stout S, et al. A scandal of invisibility: making everyone count by counting everyone. Lancet. 2007;370(9598):1569–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AbouZahr C, De Savigny D, Mikkelsen L, Setel PW, Lozano R, Lopez AD. Towards universal civil registration and vital statistics systems: the time is now. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1407–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Metrics Network. Strengthening civil registration and vital statistics for births, deaths and causes of death . Resource kit. Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harbitz ME, Tamargo M del C. Inter-American Development Bank. 2009. The significance of legal identity in situations of poverty and social exclusion: the link between gender, ethnicity, and legal identity. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brito S, Corbacho A, Osorio R. Does birth under-registration reduce childhood immunization? Evidence from the Dominican Republic. Health Econ Rev [Internet]. 2017;7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5364131/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.UNICEF. Birth registration and armed conflict. 2007.

- 7.Dow U. The Progress of nations. UNICEF. 1998. Birth registration: the “first” right. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todres J. Birth Registration: an essential first step toward ensuring the rights of all children. Hum Rights Brief. 2003;10(3):32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNICEF . Birth registration: a right from the start. Florence: Innocenti Research Centre, United Nations Children’s Fund; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.AbouZahr C, De Savigny D, Mikkelsen L, Setel PW, Lozano R, Nichols E, et al. Civil registration and vital statistics: progress in the data revolution for counting and accountability. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1373–1385. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60173-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaya Y, Data T, Lindtjørn B. Maternal mortality in rural South Ethiopia: outcomes of community-based birth registration by health extension workers. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demographic Components of Future Population Growth: 2015 Revision . United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, population division [internet] New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UN-Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16

- 14.Mathers CD, Ma Fat D, Inoue M, Rao C, Lopez AD. Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(3):171–177c. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips DE, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Atkinson C, Gonzalez-Medina D, Mikkelsen L, et al. A composite metric for assessing data on mortality and causes of death: the vital statistics performance index. Popul Health Metr. 2014;12(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikkelsen L, Phillips DE, AbouZahr C, Setel PW, De Savigny D, Lozano R, et al. A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1395–1406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNICEF . The state of the World’s children 2017: children in a digital world. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNICEF . Every child’s birth right: inequities and trends in birth registration. New York: UNICEF; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.UN Statistics Division. UNSD Demographic Statistics [Internet]. United Nations; 2017. Available from: http://data.un.org

- 20.Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID). Human Fertility Collection [Internet]. 2017. Available from: fertilitydata.org

- 21.UN Statistics Division . Principles and Recommendations for a Vital Statistics System, Revision 3 [Internet] New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, UN Statistics Division; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNICEF . Low Birthweight: Country, Regional and Global Estimates. New York: WHO; UNICEF; 2004. p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Initiative, data for Health . Strengthening CRVS systems: CRVS systems matter for sustainable development goal achievement. Melbourne: University of Melbourne; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.UN Statistics Division. Demographic Yearbook Questionnaire [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/dyb/dybquest.htm

- 25.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Volume I: Comprehensive Tables. [Internet]. UN; 2017 [cited 2017 Nov 25]. Available from: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp

- 26.Murray CJ, Lozano R, Flaxman AD, Vahdatpour A, Lopez AD. Robust metrics for assessing the performance of different verbal autopsy cause assignment methods in validation studies. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ICF International. The DHS Program: Demographic and Health Surveys [Internet]. USAID; [cited 2017 Nov 25]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/data/

- 28.University of Essex. Institute for Social and Economic Research. Understanding Society: Innovation Panel, Waves 1–8, 2008–2015. UK Data Service; 7th Edition.

- 29.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szreter S. The right of Registration: development, identity Registration, and social security—a historical perspective. World Dev. 2007;35(1):67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips DE, AbouZahr C, Lopez AD, Mikkelsen L, De Savigny D, Lozano R, et al. Are well functioning civil registration and vital statistics systems associated with better health outcomes? Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1386–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Mothers & Babies. Perinatal dynamic data displays, 2017 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/perinatal-dynamic-data-displays/data

- 33.Ministério da Saúde, Brazil. SINASC - Live Birth System. unpublished data;

- 34.Statistics Canada. Live births, by age and parity of mother, Canada, annual, CANSIM (database) In 2017. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1024509

- 35.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE). Anuario de estadísticas vitales 1997–99, 2005–14 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/demograficas-y-vitales

- 36.Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE). Nacimientos 1998–2014 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/salud/nacimientos-y-defunciones/nacimientos

- 37.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censos (INEC). Nacimientos – Bases de Datos 1992–2007, 2009–10 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/nacimientos-bases-de-datos/.

- 38.Eurostat. Population (Demography, Migration and Projections), Births and fertility data [Internet]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/population-demography-migration-projections/births-fertitily-data/database

- 39.Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) Guatemala. Estadísticas Vitales 2009–15 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ine.gob.gt/index.php/estadisticas-continuas/vitales2

- 40.Office of the Registrar General India. Vital Statistics of India based on the Civil Registration System, 2011–2015.

- 41.Statistics Bureau. Vital statistics of Japan: Natality [Internet]. Available from: http://www.e-stat.go.jp

- 42.Department of Statistics Jordan. Vital Statistics [Internet]. Available from: http://www.dos.gov.jo/dos_home_e/main/vitality/vital_index1.htm

- 43.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (México) Estadística de nacimientos : descripción de la base de datos nacional. México: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Centre for Statistics and Information. Statistics Bulletin. Deaths and births. Issues. 1—5:2012–6.

- 45.Ministerio de Salud Peru. CNV - Live Birth System. unpublished data;

- 46.Statistics South Africa. StatsOnline: Recorded Live Births (RLB) 1998–2016 [Internet]. Available from: http://interactive2.statssa.gov.za/webapi/jsf/dataCatalogueExplorer.xhtml

- 47.Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics Executive Yuan. Statistical yearbook of the republic of China, 2014. Republic of China; 2015.

- 48.United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS). Natality public-use data on CDC WONDER online database. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Division of vital statistics (DVS); 2017.

- 49.Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Estadísticas Vitales - Natalidad 1996-2015. 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Further Statistical Details: Disaggregating Estimated Birth Counts by Sex, Birthweight and Live Birth Order. A two-page document describing the methods applied to estimate birth counts disaggregated by sex, birthweight and live birth order. (DOCX 16 kb)

VSPI-B Estimates and their Component Indicators by Country. A figure for every country with available data, displaying the observed data, final VSPI-B estimate, and sub-plots for each of the five components of the VSPI. (PDF 600 kb)

Simulated Age-Sex-Parity-Birthweight Fraction Accuracy Associated with Each Indicator. A figure displaying the results of the simulation procedure. The lines demonstrate the accuracy of simulated data in terms of the fraction of births in each birth group, as compared to the underlying population. Each line represents a different component of the VSPI-B at different simulated levels of that component. (PDF 7 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this analysis can be downloaded from the following URL: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-birth-registration-database-1948-2015