Abstract

Aim:

Herein, we compare outcomes in patients treated with lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) with and without tissue confirmation.

Methods:

We reviewed 196 patients that underwent lung SBRT for presumed (100 patients) or proven non-small-cell lung cancer (96 patients) over a 10-year period and compared outcomes.

Results:

A total of 196 patients with a median age of 76 underwent lung SBRT to a median dose of 48 Gy in four fractions. Median follow up was 17 months. Local control and overall survival at 3 years was 94 and 58% for the entire group. There was no difference in overall survival, local control, regional control or distant control between the cohorts.

Conclusion:

SBRT is a safe and effective treatment for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer that are medically inoperable with comparable results in empirically treated patients.

Keywords: : lung cancer, radiation therapy, stereotactic body radiotherapy

Summary points.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy for early stage non-small-cell lung cancer has become the standard of care for inoperable patients.

Furthermore, empiric treatment of presumed early stage lung cancer without biopsy is increasingly popular, although it is unclear if radiographic and clinical data alone are sufficient to direct management.

We therefore compared the outcomes of 96 biopsy-proven and 100 clinically diagnosed early stage non-small-cell lung cancers treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy.

Empirically treated lesions were smaller (1.6 cm) compared to biopsy-proven ones (2.2 cm) and patients treated empirically had poorer pulmonary function.

The local control and overall survival at 2 years was 94% and 58% for all patients, with no difference between groups and no grade 3 or higher toxicities.

Our study confirms that stereotactic body radiotherapy is a safe and effective treatment for medically inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer.

Oncologic outcomes for empirically treated lesions were similar to the biopsy-proven group, suggesting that modern imaging and clinical history can substitute a tissue diagnosis in a high risk population.

Stage I–II non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 30% of all cases of newly diagnosed NSCLC, of which there are over 225,000 cases per year in the USA [1]. For such early stage lung cancers, surgical resection remains the primary definitive approach, assuming that there are no contraindications. For those patients unable to undergo surgical resection, radiation therapy, specifically, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), is the primary alternative and yields excellent local control [2,3]. In an ideal setting, patients will have tissue diagnosis prior to proceeding with any radiotherapy intervention. Often times, however, these patients have significant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other comorbidities which may limit even tissue diagnosis via biopsy. Increasingly, these patients are treated empirically with SBRT, which gives rise to concern for potentially overtreatment in a frail patient population [4–7]. Herein, the authors investigate and report the outcomes of patients treated at a single institution with SBRT for early stage medically inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer, both biopsy-proven and empirically managed.

Methods

We identified 431 patients treated with lung SBRT for all indications between January 2008 and June 2017 in this Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved study. Patients treated with nonablative doses or confirmed or obvious metastatic disease were excluded. All patient's had appropriate pretreatment staging with CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis and often times FDG-18 PET-CT. Taking into consideration the above exclusions, we were able to identify 196 patients meeting eligibility criteria for this study. 100 patients (51%) were treated without biopsy while 96 patients (49%) were treated with tissue confirmation of NSCLC. The former group of patients was typically treated after discussion in the multidisciplinary setting and consultation with thoracic surgery and pulmonology, having been deemed too high of a risk for any invasive procedure. All physician involved in the patient care had to be in agreement that likelihood of malignancy was high based on imaging characteristics and changes over time. Patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. . Patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | Pathological diagnosis number (% or range) | Clinical diagnosis umber (% or range) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 46 (48) | 57 (57) | NS |

| Female | 50 (52) | 43 (43) | NS |

| Median age | 77 (58–93) | 76 (45–94) | NS |

| Smoking (current or former) | |||

| Yes | 93 | 98 | NS |

| No | 3 | 2 | NS |

| Median FEV1 | 1.16 | 0.95 | NS |

| ECOG | |||

| 0 | 11 (12) | 5 (5) | NS |

| 1 | 55 (57) | 54 (54) | NS |

| 2 | 27 (28) | 38 (38) | NS |

| 3 | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | NS |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Stage: | 0.006† | ||

| – T1N0 | 68 (71) | 89 (89) | |

| – T2N0 | 28 (29) | 10 (10) | |

| – T3N0 | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Median diameter | 2.2 cm (0.8–5.3) | 1.6 cm (0.6–4.5) | <0.001† |

| Median PTV volume | 29.6 cc (2.6–122.7) | 18.3 (3.68–97.36) | 0.006† |

| Median SUV | 7.2 (1–39.7) | 4.1 (0.5–20) | 0.004† |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 (44) | – | – |

| Squamous cell | 48 (50) | – | – |

| NSCLC NOS | 6 (6) | – | – |

†Statistically significant p-values.

FEV: Forced expiratory volume; NOS: Not otherwise specified; NSCLC: Non-small-cell lung cancer; PTV: Planning target volume; SUV: Standard uptake value.

SBRT was delivered in the outpatient setting using dose and fractionation schemes left up to the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. All patients underwent a 4D noncontrast chest CT with 1.5–3 mm slices for treatment planning simulation to account for respiratory motion. A gross tumor volume was delineated on a free breathing scan and expanded on four expiratory and four inspiratory phases to generate an internal target volume. The planning target volume expansion was typically 5 mm, occasionally less if adjacent to the ribs or a central structure at the discretion of the treating physician. Linear accelerator-based radiotherapy was delivered via 8–12 coplanar 3D conformal beams with 6 MV photons. The median dose for both cohorts was 48 Gy in four fractions, ranging from 48 to 50 Gy in four to five fractions, corresponding to a biologic equivalent dose (BED10) of 100–105.6 Gy. The median dose covering 95% of the planning target volume was consistent with prescribed dose. Daily megavoltage cone beam CT was used for image guidance.

After treatment, patients were typically followed with noncontrast chest CTs or PET/CTs at least every 3 months for 1 year and every 3–6 months thereafter. Response to treatment and local/distant control was assessed via RECIST criteria [8]. Patient characteristics and morphological features, size, location, growth and maximum standard uptake value of the treated lesions, were reported if available and correlated with disease progression with univariate and multivariate analysis via Cox regression models [9]. Survival, local control (defined as control in target volume), regional control (failure in ipsilateral lung, lobe or mediastinum) and distant control (defined as new metastatic lesion or new nodule in contralateral lung) were all determined via Kaplan–Meier methodology [10]. All statistics were conducted via IBM SPSS v20 (IBM, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 103 males and 93 females with 196 treated lung lesions were included in this study. See Table 1 for complete patient characteristics. Virtually all patients had some degree of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and an extensive smoking history (median: 50 pack-years). 53 patients in the empiric group had a history of prior malignancy, with 45% having prior lung cancer. Patients treated empirically had lesions that were spiculated 56% of the time and those in the biopsy proven group were spiculated 54% of the time. Empiric patients had smaller tumors (1.6 vs 2.2 cm; p < 0.001) than those with biopsy proven lesions and a trend toward poorer pulmonary function at baseline (FEV1 0.95 vs 1.16 L; p > 0.05). 8% of patients in the biopsy proven group and 82% of patients in the empiric group had a pretreatment PET/CT scan.

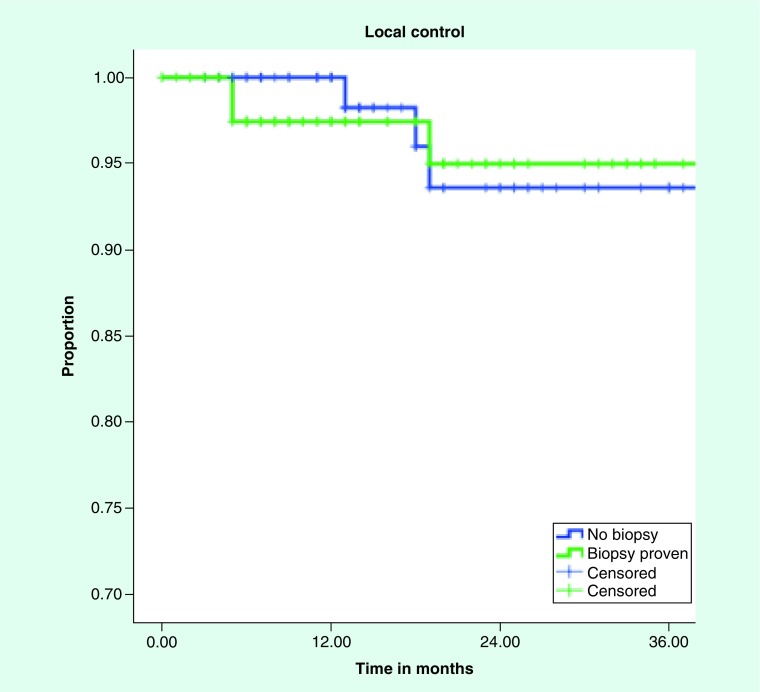

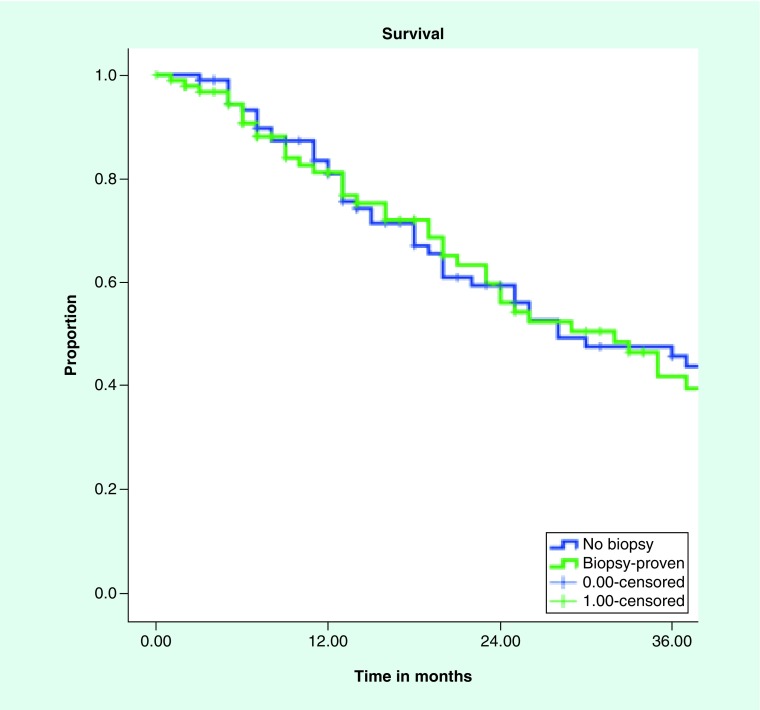

Median follow up for patients with pathologically proven NSCLC was 17 months and 14 months for those without biopsy. All patients had imaging follow up, with median number of follow up scans of two (range: 1–19). Local control and overall survival did not differ between the groups with 3 year local control of 94 and 95% for empiric treatment and biopsy proven, respectively (Figure 1). Median overall survival was 28 months and 32 months for clinical diagnosis versus pathological diagnosis, with 3 year overall survival of 45 and 46%, respectively (Figure 2). Regional control and distant control were likewise similar, with rates at 3 years of 84 and 87% for clinical diagnosis and pathologic diagnosis, respectively, for regional control. Distant control rates were 77 and 75% at 3 years for the empiric group and biopsy proven group, respectively.

Figure 1. . Kaplan–Meier curve for local control for biopsy-proven versus clinically diagnosed non-small-cell lung cancer.

Figure 2. . Kaplan–Meier curve for survival biopsy-proven versus clinically diagnosed non-small-cell lung cancer.

SBRT was very well tolerated in both groups of patient with no acute or late ≥grade 3 toxicity. Ten patients in the biopsy proven group developed grade 1–2 chest wall/rib pain correlating to SBRT location at a range from 1 month to 5 years. In the empirically treated group, six patients also developed grade 1–2 rib/chest wall pain ranging from 1 to 6 months from treating, yielding an overall chest wall syndrome rate of 8% for all patients.

Discussion

Lung cancer remains one of the most common malignancies throughout the world and affects 234,000 patients a year in the USA. It is still the leading cause of cancer death among both men and women, resulting in 154,000 deaths annually. The chance for cure remains reasonably high when found an early stage, which is occurring more given the rise in chest CT screening for patients at a sufficiently high risk [11]. Surgery remains the standard of care for patients with early operable NSCLC. Given the patient population that is affected by NSCLC, and the omnipresent risk factors and comorbidities, these patients are oftentimes rendered medically inoperable [12]. These patients are typically managed with SBRT, which has been shown in the prospective setting to be safe and efficacious [2,3]. A subset of these medically inoperable patients will have such poor pulmonary reserve that even a diagnostic biopsy will be avoided given the risk of pneumothorax and potential for significant harm or even death [13]. Increasingly, these patients are being treated empirically [5–7].

The largest series on the topic is from a group in the Netherlands that compared outcomes in a cohort of close to 600 patients, of which 65% were treated empirically [7]. These patients were treated to 60 Gy using fractionation schemes ranging from 3 to 8 fractions, yielding BED10 of 105–180. Outcomes did not differ between the groups, with 3-year overall survival and local control rates of 55 and 90%, respectively. Treatment was well tolerated in that study, with <5% of patients experiencing any grade 3 or greater toxicity.

A group from Japan published a similar study of their outcomes from their experience treating clinically diagnosed pulmonary nodules and biopsy proven nodules with SBRT [6]. That study included 173 patients with 33% being managed empirically (much less proportion compared with the Netherlands [7]). Patients underwent SBRT to doses ranging from 40 to 50 Gy in five fractions, yielding a BED10 range of 72–100. Three year overall survival was 55% and 3 year local control was slightly inferior compared with the above data [7], with rates of 80 and 87% (p = 0.73) for clinically diagnosed versus biopsy proven. Local control may have been slightly reduced due to use of dose fractionation schemes with a BED10 <100, which has been shown to correlate with both local control and overall survival [14]. Safety data were not published in that series.

The USA has a published experience as well treating lung nodules without tissue confirmation of malignancy. A series from UC-San Diego reviewed outcomes in 55 patients, of which 42% were treated empirically [4]. SBRT was delivered to a dose of 48–56 Gy in 4–5 fractions, yielding BED10 all greater than 100. Patient characteristics were similar in both groups. Local control was 93% and overall survival at 1 year was reported as 83%, with no difference between cohorts. In this study, there was a single episode of acute grade 3 esophageal toxicity, but no late grade 3 or higher toxicity.

Interestingly, the group from Yale published an analysis of the National Cancer Database looking at rates of lung SBRT with and without biopsy over time. They examined data from close to 7000 patients treated between 2003 and 2011. A very high proportion of these patients had tissue confirmation prior to SBRT, 95% overall. Over time, there was a trend toward increased use of SBRT without a biopsy. Other factors influencing empiric treatment were tumor size, location and medical inoperability. The results of this study seem to indicate an increased comfort with empiric treatment with the passage of time and continued documentation of safety and efficacy of lung SBRT.

The results presented in the current study mimic those discussed above, with local control values eclipsing 90% at 2–3 years, with an expected lower overall survival given the extensive comorbidities in this frail patient population. Similar to the current literature we were not able to discern any differences in outcome based on presence or absence of tissue confirmation, despite differences in distribution of larger, higher T-stage, and more avid tumors in the biopsy proven arm. Out of note, our series seemed to have a higher proportion of empirically treated lesions (51%) compared with other North American groups, especially in light of the data presented from the NCDB study cited above. This dissimilarity may indicate a higher proportion of frailer medically inoperable patients in our population, or perhaps a higher comfort level within our system to treat empirically based on imaging characteristics following a multidisciplinary discussion in our weekly thoracic oncology conference.

Given the retrospective nature of this study one must keep in mind potential selection bias and other inherent weaknesses associated with such studies. In addition, with empiric treatment, when looking at excellent outcomes one must always wonder what the true incidence of cancer being present was at the time of treatment; especially considering that smaller and less avid tumors were more often present in the empiric treatment cohort. Consideration must also be made that these nodules could have been metastases from a past primary lung cancer or malignancy from another site, although rates of distant and regional progression would be expected to be higher if that were the case. Additionally, another limit of this series is lack of follow up in terms of any treatment delivered after progression, which may influence the overall survival results seen here.

Conclusion

The current study presents another large series of patients treated with SBRT for both biopsy proven and presumed lung cancer, yielding no difference in excellent outcomes. The authors strongly encourage tissue confirmation whenever possible, but the growing body of literature further supported by this series should help to ease any potential anxiety of practitioners hesitant to treat frail patients without a biopsy. Multidisciplinary discussion and review is still extremely valuable, and certainly played a significant role in deciding to treat almost half of our patient population empirically.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Open access

This work is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

References

- 1.Groome PA, Bolejack V, Crowley JJ, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: validation of the proposals for revision of the T, N, and M descriptors and consequent stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007;2(8):694–705. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812d05d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann P, Nyman J, Hoyer M, et al. Outcome in a prospective Phase II trial of medically inoperable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(20):3290–3296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070–1076. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haidar YM, Rahn DA, 3rd, Nath S, et al. Comparison of outcomes following stereotactic body radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer in patients with and without pathological confirmation. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2014;8(1):3–12. doi: 10.1177/1753465813512545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutter CE, Corso CD, Park HS, et al. Increase in the use of lung stereotactic body radiotherapy without a preceding biopsy in the United States. Lung Cancer. 2014;85(3):390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda A, Kunieda E, Sanuki N, Aoki Y, Oku Y, Handa H. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for solitary pulmonary nodules clinically diagnosed as lung cancer with no pathological confirmation: comparison with non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verstegen NE, Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy following a clinical diagnosis of stage I NSCLC: comparison with a contemporaneous cohort with pathologically proven disease. Radiother. Oncol. 2011;101(2):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi HC, Kim JH, Kim HS, et al. Comparison of the RECIST 1.0 and RECIST 1.1 in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. J. Cancer. 2015;6(7):652–657. doi: 10.7150/jca.11794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meier ELKaP. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Lung Screening Trial Research T. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogart JA, Scalzetti E, Dexter E. Early stage medically inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2003;4(1):81–88. doi: 10.1007/s11864-003-0034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox JE, Chiles C, McManus CM, Aquino SL, Choplin RH. Transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy: variables that affect risk of pneumothorax. Radiology. 1999;212(1):165–168. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.1.r99jl33165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (HypoFXSRT) for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: updated results of 257 patients in a Japanese multi-institutional study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007;2(7 Suppl. 3):S94–S100. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318074de34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]