Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to undertake a contemporary review of the impact of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) targeted at patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Methods

We conducted searches of PubMED, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library of Controlled Trials (up until 30 November 2017) using key terms related to exercise-based CR and AF. Randomised and non-randomised controlled trials were included if they compared the effects of an exercise-based CR intervention to a no exercise or usual care control group. Meta-analyses of outcomes were conducted where appropriate.

Results

The nine randomised trials included 959 (483 exercise-based CR vs 476 controls) patients with various types of AF. Compared with control, pooled analysis showed no difference in all-cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 1.08, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.53, p=0.64) following exercise-based CR. However, there were improvements in health-related quality of life (mean SF-36 mental component score (MCS): 4.00, 95% CI 0.26 to 7.74; p=0.04 and mean SF-36 physical component score: 1.82, 95% CI 0.06 to 3.59; p=0.04) and exercise capacity (mean peak VO2: 1.59 ml/kg/min, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.08; p=0.04; mean 6 min walk test: 46.9 m, 95% CI 26.4 to 67.4; p<0.001) with exercise-based CR. Improvements were also seen in AF symptom burden and markers of cardiac function.

Conclusions

Exercise capacity, cardiac function, symptom burden and health-related quality of life were improved with exercise-based CR in the short term (up to 6 months) targeted at patients with AF. However, high-quality multicentre randomised trials are needed to clarify the impact of exercise-based CR on key patient and health system outcomes (including health-related quality of life, mortality, hospitalisation and costs) and how these effects may vary across AF subtypes.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, exercise training, meta-analysis, health-related quality of life

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Previous meta-analyses have shown that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) targeted at patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) can improve short-term (up to 6 months) exercise capacity.

However, given the lack of high-quality evidence, exercise-based CR is not formally recommended in current international guidelines for the management of AF.

What does this study add?

This contemporary review confirms that exercise-based CR for AF improves exercise capacity in the short term compared with a no exercise control.

This review also shows improvements in health-related quality of life, cardiac function and symptom burden.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Additional evidence is needed to inform the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the provision of exercise-based CR specifically targeted for those with AF.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and associated with increased risks of stroke, heart failure, dementia and death.1 AF has a prevalence of approximately 2% in adults and increasing incidence, mainly due to the ageing population.2 3 AF is a highly heterogeneous condition split in to five diagnostic categories: first-diagnosed AF (patient presents with AF for the first time), paroxysmal AF (self-limiting and usually the rhythm converts spontaneously to sinus (normal) rhythm within 48 hours), persistent AF (AF episode lasts longer than 7 days, or requires cardioversion), long-standing persistent AF (duration of AF exceeds 1 year) and permanent AF (accepted by the patient (and physician) and no rhythm control interventions are used).4 Patients with AF can experience palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue, dizziness and syncope (fainting), depression, anxiety and reduced exercise capacity.3–6

Current AF management mainly focuses on rate and rhythm control and reducing stroke risk and its associated morbidity and mortality.4 However, although effective in managing symptoms and stroke risk, current treatments do not focus on patients’ exercise capacity, ability to self-manage and mental health.7–9 Poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL) therefore remains a common and important problem of patients with AF receiving conventional medical therapy. HRQoL in patients with AF has been shown to be lower than age and sex-matched members of the general population and other cardiac groups, including coronary heart disease (CHD).9 Beyond medical management, evidence suggests AF may be controlled by improving lifestyle.10 11 One aspect of lifestyle therapy that is poorly understood, with respect to AF, is regular exercise.12

Mechanisms by which exercise may improve health outcomes for patients with AF include atrial remodelling, antiarrhythmic effects via changes in autonomic control, reduced blood pressure, reduced bodyweight and reduced lipids.13 For example, a study evaluated the long-term impact of weight loss on rhythm control of 355 obese patients (body mass index (BMI) ≥27 kg/m2) with AF. Long-term sustained weight loss (≥10%) was associated with significant reduction of AF burden and maintenance of sinus rhythm.14 Exercise has also been shown to stimulate improvements in mental health through improvements in self-efficacy and reduced inflammation.15 16

A substantive body of evidence supports the benefits of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) for CHD (post-myocardial and post-revascularisation)17 18 and heart failure populations.12 A recent meta-analysis of 33 randomised trials found that exercise-based CR reduced the risk of overall and heart failure-specific hospitalisation and resulted in improvements in HRQoL compared with usual medical care.19 AF is a common comorbidity in patients with CHD and heart failure referred to exercise-based CR. However, given the sparse evidence for CR specifically targeted for patients with AF, the 2012 European Society of Cardiology and 2011 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for the management of AF do not formally recommend rehabilitation.4 20 21

Since these guidelines were published, a Cochrane review in 2017 has found that exercise-based rehabilitation programmes targeted at AF patients significantly increased their exercise capacity (standardised mean difference (SMD): 0.86, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.26) compared with no exercise control. However, only a small volume of evidence (six randomised trials in 421 patients with AF) of moderate to very low-quality and of short-term follow-up (up to 6 months) was identified and little or no data were available on the impact on HRQoL or clinical events, such as mortality and hospitalisation.

Aware that a number of trials have been published since this 2017 Cochrane review, we sought to undertake a de novo systematic review and meta-analysis to provide a contemporary summary of the impact of exercise-based CR specifically aimed at patients with AF.

The specific aims of this review were to: (i) investigate if exercise-based CR reduces the risk of mortality and hospitalisation of patients with AF; (ii) to identify if markers of cardiac function and AF risk are altered with exercise-based CR; (iii) and to confirm whether exercise-based CR increases exercise capacity and HRQoL in patients with AF.

Methods

Search strategy

Potential studies were identified by conducting systematic searches of PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library of Controlled Trials up until 30 November 2017. Searches included a mix of MeSH and free text terms related to the key concepts of exercise-based CR, atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia, heart rate and heart rate variability. In addition, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and reference lists of papers were hand searched for additional studies. One reviewer (NAS) conducted the search and full articles were assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (NK and NAS) using the inclusion criteria. A sample search strategy is presented in online supplementary files. Authors were contacted and asked to provide clarification of study information if needed.

Study type and participants

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs of exercise training in adult patients with AF were included. Abstracts and non-English language studies were excluded.

Intervention

Exercise-based CR was defined to allow for inclusion of a broad range of physical activities, including aerobic, resistance exercise training, combined training (aerobic and resistance), yoga, pilates, Tai Chi and hydrotherapy. Additionally, the physical therapies of Functional Electrical Stimulation and Inspiratory Muscle Training were included in the definition of exercise-based CR for the purpose of this review. To be included in the review, studies had to compare an exercise-based CR intervention to no exercise or usual care, or ‘other exercise’ control groups and the duration of the exercise-based CR had to be a minimum of 4 weeks. We also included trials that included exercise-based CR with other interventions including education and psychological support as many contemporary rehabilitation programmes use all three components.

Outcomes

Primary

All-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalisation.

HRQoL: any validated HRQoL questionnaire was included.

Exercise capacity, for example, peak VO2 or 6 min walk distance.

Secondary

Measures of cardiac function, for example, resting heart rate.

Other clinical risk factors associated with AF, for example, AF burden or AF symptoms.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (NAS, NK) extracted the following information for each study: (1) author, year of publication and study design; (2) AF patient demographic and clinical characteristics (eg, age or type of AF); (3) exercise intervention characteristics (eg, duration, modality, frequency, intensity); (4) number of patient events (binary outcomes), or mean and SD (or SE, p value or 95% CIs) (continuous outcomes); (5) characteristics of assessment methodology for AF and (6) reporting of adverse events and intervention compliance.

Data synthesis

Statistical analyses were performed using Revman V.5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). For meta-analysis of binary data, risk ratios (RRs) were calculated. Individual meta-analyses were completed for continuous data by using the mean baseline follow-up change and SD. Where the mean change and SD were not reported, this was calculated by subtracting the follow-up mean from the baseline mean, and Revman V.5.3 enabled calculations of SD using number of participants in each group, within-group or between-group p values or 95% CI. In cases where exact p values are not provided, we used default values, for example, p<0.05 becomes p=0.049, p<0.01 becomes p=0.0099 and p=not significant becomes p=0.051. Where data were reported as median, the median was assumed to equal the mean. Data not provided in main text or tables were extracted from figures. For continuous data, MD was used where outcome measures were homogenous. Where outcome measures were measured by different methods, SMD was used. Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 test. Values ranged from 0% (homogeneity) to 100% (high heterogeneity).22 A fixed effects meta-analysis model was used when there was evidence of no statistical heterogeneity (ie, I2 statistic ≤50%) and a random effects inverse variance model was used when the I2 statistic >50%. We judged statistical significance based on 5% level of significance and reported pooled mean results with 95% CIs. Where a study included multiple intervention groups and a control group, each intervention group was considered separately and the sample size of the control group was divided by the number of intervention groups to eliminate over inflation of the sample size. If data were reported for multiple time points during the intervention, only the data at the end of the intervention were extracted as long as data were available for both the intervention and control group. Where two publications referred to the same study population, the publication with the highest number of participants was used. Visual inspection of funnel plots23 was used to assess risk of publication bias.

Study quality

Study quality was assessed using the TESTEX; the Tool for assessment of study quality and reporting, designed specifically for use in exercise training studies.24 This is a 15-point scale that assesses study quality (maximum 5 points) and reporting (maximum 10 points). Two reviewers (RST and NAS) independently conducted quality assessment. A study quality score <10 was considered low quality. If relevant subanalyses were conducted by removing low-quality studies from pooled analyses.

Results

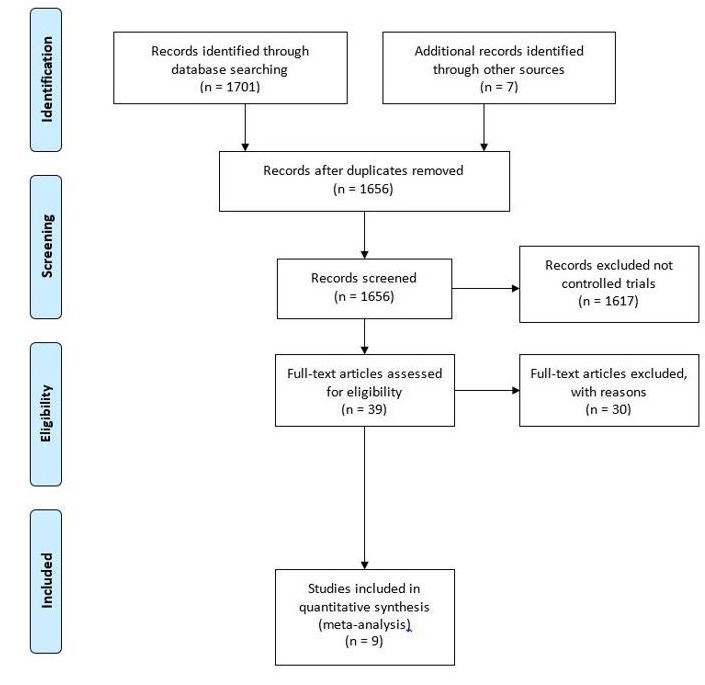

Our initial search identified 1701 titles, and hand searching a further 7 potential studies for inclusion. Fifty-two duplicate studies were removed, and a further 1617 papers excluded as they were not RCTs or non-RCTs. Thirty studies were excluded at full text screening as they were not studies of exercise-based CR in adults with AF. Also, 13 were acute (single exercise session) studies, 16 were not AF studies and 1 was a paediatric study. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram (figure 1) describes the selection process. Nine studies (nine publications) were included in this analysis2 10 25–31 (see table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Table 1.

Included studies

| Study | Inclusion criteria | Intervention: control | Exercise/control | Outcomes |

| Hegbom 25 | Patients with chronic AF,<75 years. |

Exercise 8 weeks, three sessions/week. Supervised, 1.25 hours, aerobic exercise: 5 min warm-up, 3×15 min periods of aerobics @ 70%–90% HRmax interrupted by strengthening exercise (back, thighs and stomach), followed by a 5 min cool-down and 15 min of stretching. Sessions completed @ one of two rehabilitation Centres. Control Usual care. |

15/15 randomised 13/15 analysed |

Heart rate variability Maximal heart rate Resting heart rate Cumulated workload (W) Exercise time max. (min) QoL (SF-36) |

| Luo 2 | Heart failure patients with LVEF <35%. Sub-analysis of those with AF from HF ACTION trial. |

Exercise 12 weeks, three sessions/week. Supervised aerobic exercise (walking, treadmill, or cycle ergometer), followed by transition to a home-based exercise programme for an additional 2 years. Control Usual care. |

193/189 randomised and analysed | 6MWD Peak VO2 QoL (KCCQ) All-cause mortality/ hospitalisation Cardiovascular mortality/HF hospitalisation |

| Malmo 26 | Patients with non-permanent AF (paroxysmal or persistent) |

Exercise 12 weeks, three sessions/week. Aerobic (walking/running), 10 min warm-up @ 60%–70% HRpeak, then 4×4 min intervals @ 85%–95% of HRpeak with 3 min of active recovery @ 60%–70% HRpeak between intervals. Control Usual care. |

26/25 randomised and analysed | Time in AF AF symptoms and severity Blood pressure Resting heart rate Peak heart rate Cardiac volumes (ejection fraction) QoL (SF-36) Peak VO2 lipid status (TC, HDL, LDL, TG) hsCRP BMI, weight activity |

| Osbak 27 | Adults with permanent AF. |

Exercise 12 weeks, three sessions/week, @ 70% maximal exercise capacity (Borg scale scores 14–16). Total exercise duration was 60 min 3, minimum 30 min @ 70% maximal exercise capacity. Control Usual care. |

25/24 randomised 24/23 analysed |

CO (maximal and resting) Maximal heart rate Resting heart rate Blood pressure Heart rate reserve 6MWD Maximal power (W) QoL (MLHF-Q and SF-36) ANP, NT-pro-BNP Adverse events |

| Pippa 28 | Patients diagnosed with AF at least 3 months prior, and taking anticoagulant treatment for at least 2 months. |

Exercise 16 weeks, two sessions/week. 90 min sessions of qi gong training. Qi gong refers to a set of static exercises. Control Usual Care. |

22/21 randomised and analysed | 6MWD BMI Lipids (TC, HDL) Homocysteine Ejection fraction Adverse events |

| Risom 29 | Consecutive patients planned for treatment with radiofrequency catheter ablation,≥18 years. Paroxysmal or persistent AF. |

Exercise 12 weeks, three sessions/week, graduated cardiovascular training based on Borg 15-point scale and strength exercises. Control Usual care. |

105/105 randomised* | Peak VO2

Maximal power (W) STS Max. blood pressure QoL (SF-36, HADS) EHRA score Mortality, adverse events |

| Skielboe 10 | Patients with paroxysmal/ persistent AF. |

Exercise 12 weeks, two sessions/week, 60 min/session, high Intensity – (80% of maximal RPE). Comparator 12 weeks, two sessions/week, 60 min/session, low Intensity (50% of maximal RPE). |

38/38 randomised† 26/29 analysed† |

Burden of AF (time spent in AF) Peak VO2 Hospital admissions Adverse events |

| Wahlstrom 31 | Patients with paroxysmal AF, necessitating pharmacological treatment. |

Exercise 12 weeks, one session a week, 60 min group session of yoga (Mediyoga) and encouraged to practice at home. Control Usual care. |

40/40 randomised 33/36 analysed |

QoL (SF-36, EuorQoL-5D) Resting heart rate Blood pressure |

| Zeren 30 | Patients with permanent AF, LVEF >40%. |

Exercise 12 weeks, 2×15 min sessions, 7 days/week. Inspiratory muscle training a@ 30% MIP. Control Usual care. |

19/19 randomised 17/16 analysed |

Pulmonary function Respiratory muscle strength Adverse events |

*Different numbers for analysis at different time points for different outcomes.

†Performed ITT analysis and per protocol analysis.

ACR, Albumin: Creatinine ratio; AF, Atrial Fibrillation; ANP, Atrial Natriuretic Peptide; BMI, Body mass index; ERHA, European Heart Rhythm Score; HADS, Hospital anxiety and depression score; HD, High density lipoprotein; HF, Heart failure; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LDL, Low density lipoprotein; MLHF-Q, Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire; 6MWD, 6 minute walk distance; NT-Pro-BNP, N-terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide; QoL, Quality of life; RPE, Rate of Perceived Exertion; SF-36, Short form-36; STS, Sit-to stand test; TC, Total cholesterol; TG, Triglycerides; eGFR, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; hsCRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein.

Trial and patient characteristics

Eight RCTs compared exercise-based CR with control participants, while one RCT compared high-intensity exercise training versus exercise at lower intensity.10 The total number of participants in the nine included studies yielded 959 participants, 483 allocated to exercise training and 476 to control. One study, in addition to the exercise component, also included a psycho-educational part of the intervention.29

Study quality and risk of bias

Median TESTEX score was 12 out of 15. Monitoring of physical activity in the control group (3/9 studies) and assessment of energy expenditure during training (4/9 studies) were the only two items not performed by at least 50% of studies; see table 2. Two studies produced a TESTEX score <10.

Table 2.

Assessment of study quality and reporting using Tool for the assessment of Study quality and reporting in Exercise (TESTEX)

| Study | Eligibility criteria specified | Randomisation details specified |

Allocation concealed | Groups similar at baseline | Assessors blinded | Outcomes measures assessed >85% participants* | Intention to treat analysis | Reporting between-group statistical comparison† | Point measures and measures of variability | Activity monitoring in control group | Relative exercise intensity constant | Exercise volume and energy expenditure | Overall TESTEX (/15) |

| Hegbom 25 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Luo 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Malmo 26 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Osbak 27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Pippa | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Risom 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Skielboe 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Wahlstrom 31 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Zeren 30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Total | 9 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

*Three points possible—one point if adherence >85%, one point if adverse events reported, one point if exercise attendance is reported.

†Two points possible—one point if primary outcome is reported, one point if all other outcomes reported. 0 awarded if no mention was made of this criteria or if it was unclear.

Key: total out of 15 points.

Primary outcomes

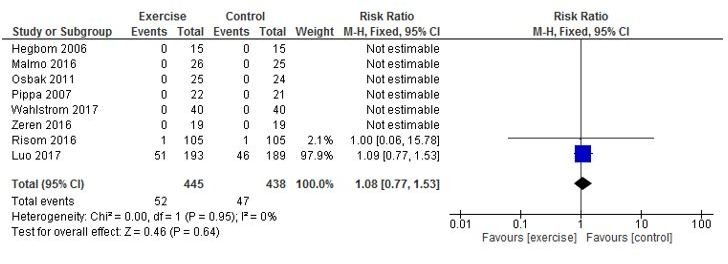

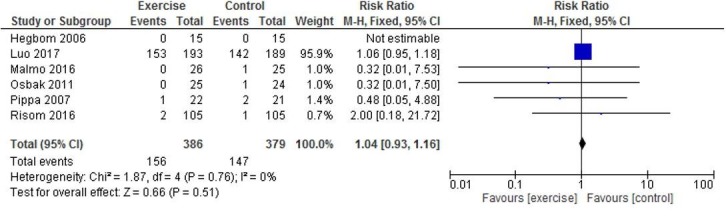

Mortality and hospitalisation

Evidence from pooled analysis of eight studies2 25–31 showed 52 deaths in 445 (11.7%) exercising participants and 47 deaths in 438 (10.7%) control participants. There was no significant difference in pooled RR between exercise-based CR and control groups (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.53, p=0.64, I2=0%) (figure 2). There were 156 occurrences of either all-cause mortality or hospitalisation reported in 386 (40.4%) intervention participants and 147 occurrences in 379 (38.7%) control participants (RR 1.04, 95 CI% 0.93 to 1.16, p=0.51, I2=0%) (figure 3).

Figure 2.

All-cause mortality.

Figure 3.

All-cause mortality or hospitalisation.

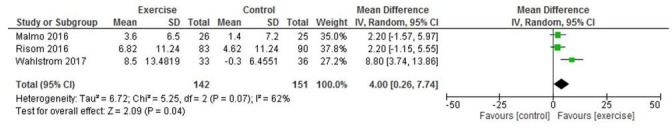

HRQoL

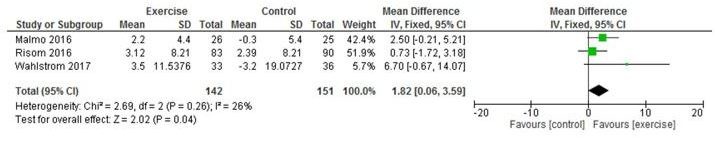

Five studies reported on HRQoL using SF-36; however, Hegbom et al25 only reported combined intervention and control data and therefore could not be pooled. Three studies reported SF-36 MCS26 29 31; pooled analyses showed a significant improvement in MCS in exercise-based CR versus control participants (MD 4.00, 95% CI 0.26 to 7.74; p=0.04, I2=62%) (figure 4). Three studies reported SF-36 physical component scores (PCS)26 29 31; pooled analyses showed a significant improvement in PCS in exercise-based CR versus control participants (MD 1.82, 95% CI 0.06 to 3.59; p=0.04, I2=26 %) (figure 5). Analyses also demonstrated a significant improvement in the SF-36 subscale of vitality in exercise-based CR versus control (MD 8.33, 95% CI 2.15 to 14.52 p=0.008, I2=54%) (see online supplementary file), and SF-36 general health (MD 7.54, 95% CI 4.63 to 10.44, p<0.001, I2=50%) (see online supplementary file). One study2 measured self-reported HRQoL using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) with only minimal improvements observed from exercise-based CR.

Figure 4.

Change in SF-36 mental component score.

Figure 5.

Change in SF-36 physical component score.

openhrt-2018-000880supp001.docx (275.5KB, docx)

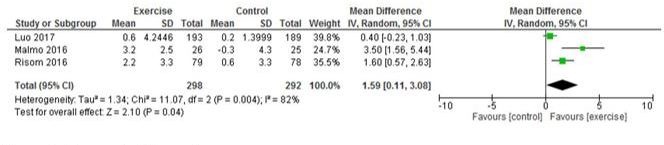

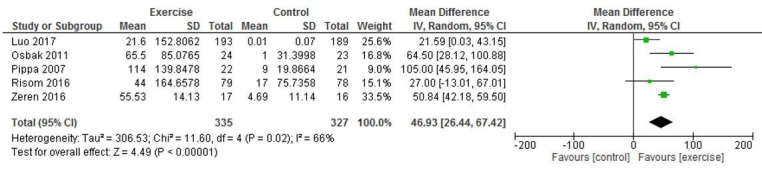

Exercise capacity

Three studies reported peak VO2 (2, 26, 29) and pooled analysis showed a significant improvement in intervention vs control participants for peak VO2 (MD 1.59 ml/kg/min, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.08; p=0.04 I2=82%) (figure 6). Five studies reported 6 min walk distance and pooled analysis showed a significant improvement in intervention versus control participants (MD 46.93 m, 95% CI 26.44 to 67.42; p<0.001, I2=66%) (figure 7).

Figure 6.

Change in VO2 peak.

Figure 7.

Six-minute walk test.

Secondary outcomes

Cardiac function

Four studies reported resting heart rate25–27 31; however, Hegbom et al25 only provided combined intervention and control data. Pooled analysis of available data from three studies26 27 31 showed resting heart rate to be reduced in exercising versus control participants (MD −4.61 beats/min, 95% CI −7.42 to −1.80, p=0.001); I2=45% (see online supplementary file). Maximal heart rate was reduced in exercising versus control participants; (MD −2.95 beats/min, 95% CI −5.31 to −0.59, p=0.01; I2=50%) (see online supplementary file). Left ventricular ejection fraction was assessed by measuring the volume of blood ejected from the left ventricular chamber using MRI26 and two-dimensional echocardiography.28 Left ventricular ejection fraction was significantly increased by exercise-based CR versus control (MD 4.31%, 95% CI 2.12 to 6.51, p<0.001; I2=0%) (see online supplementary file). One study reported left atrial volume to be unchanged after exercise-based CR versus control (MD 0.0 cm3, 95% CI-6.49 to 6.49, p=1.00).

AF burden and symptoms

Two studies reported time spent in AF.10 26 Malmo et al26 observed a decrease in mean time spent in AF from 8.1% to 4.8% in the exercise-based CR group, which was significantly different from controls (MD 7.6%, 95% CI 2.0 to 13.0, p=0.001). Three studies reported on AF symptoms25 26 29; however, Hegbom only reported combined intervention and control data. Malmo et al26 reported changes in AF symptoms, assessed by the AF Symptoms and Severity Checklist, with significant reductions in symptom frequency and severity, compared with controls (p<0.01). Risom et al29 reported no significant difference in European Heart Rate Association (EHRA) scores between exercise-based CR and control groups.

Clinical risk factors

Pooled data from three studies26–28 indicated a decrease in systolic and diastolic BP; however, this was not statistically significant (see online supplementary file). Two studies reported BMI changes. A statistically significant change in BMI compared with controls was observed by Malmo et al26, while no change was observed by Pippa et al.28 Similarly, in patients with permanent AF, Osbak et al27 failed to observe any changes between groups for lean body mass or fat percentage. Malmo et al observed significant decreases in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein and triglycerides compared with controls. In contrast, Pippa et al reported no change in total cholesterol.

Analyses of high-intensity versus lower-intensity exercise training

Skielboe et al10 reported no significant differences between groups exercising at higher versus lower intensities for any of the outcome measures.

Publication bias

Examination of funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias.

Discussion

This updated systematic review and meta-analysis provides a contemporary summary of the impact of exercise-based CR aimed at patients with AF.12 We included data from nine randomised trials in a total of 959 patients with various types of AF. Our study shows improvements in exercise capacity, HRQoL and various measures of cardiac function, and AF symptom burden in the short term (up to 6 months) following exercise-based CR compared with no exercise control. However, there was insufficient evidence to determine if the benefits of exercise-based CR vary across types of AF, to assess the impact of CR on the risk of mortality or hospitalisation or to determine the optimal exercise training intensity to elicit beneficial health outcomes.

Comparison with previous studies

Compared with the 2017 Cochrane review, our study included an additional three randomised trials and an additional 538 patients with AF. Our pooled analysis failed to show a reduction in mortality and hospitalisation due to insufficient evidence, consistent with the previous Cochrane review.12 However, our findings of the positive impact of exercise-based CR on exercise capacity are consistent with this previous Cochrane review. Our analysis showed that mean peak VO2 was improved by about 1.6 ml/kg/min after exercise-based CR which corresponds to ~0.5 METs in people with AF. These findings correspond with a meta-analysis of 41 trials of people with CHD and heart failure which found a pooled MD of 3.3 ml/kg/min for VO2 in favour of CR32 (corresponding to ~1.0 METs). It would take a typically deconditioned cardiac patient with AF with a peak VO2 value of ~13 ml/kg/min to a value >14 ml/kg/min.33 34 This is clinically meaningful as it would reduce the mortality and morbidity risk of such a patient35 and represents an absolute change of 4%–5% which would be noticeable in terms of associated symptoms, for example, dyspnoea. The observed mean improvement in 6 min walk distance of 47 m is also above the minimally clinically important difference of 41.8 m previously reported.36 Importantly this updated review provides additional evidence of the potential benefit on HRQoL.

Our analyses showed that exercise-based CR can impact on the various subscales of HRQoL. Both the MCS and PCS of the SF-36 demonstrated significant improvements.12 It is has been proposed that compared with disease-specific measures generic HRQoL measures (such as the SF-36) may lack the sensitivity to AF-specific symptoms and specific barriers unique to AF.37 However, given that we were able to see improvements using a generic HRQoL instrument other factors may also be relevant here. For example, non-specific factors such as depression, anxiety and fear of social isolation associated with the risk of a stroke are likely to a major concern for people with AF.38

Resting heart rate was reduced in exercising participants possibly reflecting better rate control which is important in AF.39 40 Previous work has shown a j-shaped relationship between heart rate and mortality in people with AF.39 Maximal heart rate was also reduced by about 1.7 beats per minute less than resting heart rate reduction. However, heart rate reserve (the difference between resting and maximum heart rate) was not reported in any of the included studies. Impaired heart rate reserve in patients with permanent AF treated according to a strict rate-control strategy is associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation for patients with heart failure.41 It is important to note that there is no defined clinical end point for heart rate control. For example, the RACE-II trial compared lenient rate control (target resting heart rate <110 bpm) to strict rate control (target resting heart rate <80 bpm) and found no differences in mortality, hospitalisation, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding and arrhythmic events (HR 0.84; 90% CI 0.58 to 1.21).42

Our analysis showed left ventricular ejection fraction was significantly increased by exercise-based CR versus control participants. This is especially important in people with AF who derive great benefit from improved systolic function.43 Limited data from only one study26 in this analysis reported left atrial volume to be unchanged after exercise-based CR versus control. Larger left atrial size is a strong predictor of AF initiation and propagation, and therefore, any reduction in this parameter is likely to increase the likelihood of a rhythm control strategy.44 Data on ejection fraction were collected using MRI26 and two-dimensional echocardiography.28 Both of these approaches use Simpson’s rule to calculate ventricular volume, which brings some consistency. However neither study mentioned, number of beats nor HR at time of recording which given the heterogeneous nature of AF in any given patient could have been a limitation. Finally, it is important to recognise that diastolic function is being recognised as an important risk factor for AF.45 Left ventricular diastolic function has been shown to be able to predict the occurrence of AF even when other cardiovascular risk factors are controlled for.46 However, there were insufficient data in the included studies to allow meaningful analyses.

Strengths and limitations

We believe this to be the most comprehensive systematic review of exercise-based CR for AF to date and found no evidence of publication bias. However, we recognise this study had a number of limitations. First was the small number of eligible studies and considerable variability in terms of their interventions, participants and outcomes. As a result, data pooling was limited to small patient numbers and to small number of common outcomes. The exercise-based CR programmes varied greatly between studies with respect to exercise intensity, duration, frequency and modality. Second, AF burden is difficult to measure due to its heterogeneous nature, and the fact that frequency of symptom severity varies between different AF subtypes. Finally, given the lack of studies and lack of availability of individual patient data no subgroup analyses in relation to the clinical sub-types of AF (ie, first-diagnosed AF, paroxysmal AF, persistent AF, long-standing persistent AF and permanent AF) could be carried out.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Exercise-based CR represents a promising intervention for people with AF. However, due to insufficient evidence, we believe it is premature to recommend exercise-based CR targeted at patients with AF. Future large-scale trials with well-developed and delivered interventions should be conducted to understand if exercise-based CR can elicit long-term effects on HRQoL and other important clinical outcomes in people with AF. Such trials should also be adequately powered to investigate potential variations in the impact of exercise-based CR across the various clinical subtypes of AF.

Conclusion

Exercise capacity, measures of cardiac function, AF symptom burden and HRQoL were seen to improve in the short term (up to 6 months) with exercise-based CR in people with AF compared with no exercise control. There appeared to be no differences in outcomes between exercise at high and lower intensity. Further high-quality randomised trials which target the specific subtypes of AF are needed to definitively assess the impact of exercise-based CR on key patient and healthcare system outcomes, including HRQoL, clinical events and costs.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed significantly to the submitted work. NAS was the team leader, who also assisted with study inclusion/exclusion, data extraction/analysis and writing and editing of both the main text and supplementary files. MJP contributed to the initial idea conception, conducted some of the data extraction, study quality assessment and assisted with manuscript writing. NK contributed to the initial idea conception, conducted much of the data extraction, study quality assessment and assisted with manuscript writing. JDL contributed to the initial idea conception, conducted some of the data extraction, study quality assessment and assisted with manuscript writing. RST contributed the initial idea conception, verified the data extraction, study quality assessment and assisted with manuscript writing. JLC assisted with manuscript writing. SSR contributed to the manuscript writing.

Funding: This publication presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its NIHR Senior Investigator award (Grant Reference Number NF-SI-0514-10155).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Iwasaki YK, Nishida K, Kato T, et al. Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation 2011;124:2264–74. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Luo N, Merrill P, Parikh KS, et al. Exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1683–91. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ball J, Carrington MJ, McMurray JJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation: profile and burden of an evolving epidemic in the 21st century. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:1807–24. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, et al. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med 2002;113:359–64. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01236-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kang Y, Bahler R. Health-related quality of life in patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;3:71–6. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2003.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thrall G, Lane D, Carroll D, et al. Quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med 2006;119:448.e1–448.e19. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang L, Gallagher R, Neubeck L. Health-related quality of life in atrial fibrillation patients over 65 years: a review. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:987–1002. 10.1177/2047487314538855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarkesmith DE, Pattison HM, Khaing PH, et al. Educational and behavioural interventions for anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD008600 10.1002/14651858.CD008600.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skielboe AK, Bandholm TQ, Hakmann S, et al. Cardiovascular exercise and burden of arrhythmia in patients with atrial fibrillation - A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170060 10.1371/journal.pone.0170060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Van Gelder IC, et al. Comprehensive risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation: emerging diagnostic and therapeutic options--a report from the 3rd Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace 2012;14:8–27. 10.1093/europace/eur241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Risom SS, Zwisler AD, Johansen PP, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD011197 10.1002/14651858.CD011197.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gallagher C, Hendriks JM, Mahajan R, et al. Lifestyle management to prevent and treat atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016;14:799–809. 10.1080/14779072.2016.1179581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, et al. Long-term effect of goal-directed weight management in an atrial fibrillation cohort: A long-term follow-up study (LEGACY). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2159–69. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Euteneuer F, Dannehl K, Del Rey A, et al. Immunological effects of behavioral activation with exercise in major depression: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry 2017;7:e1132 10.1038/tp.2017.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med 2004;116:682–92. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heran BS, Chen JMH, Ebrahim S. Europe PMC Funders Group Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2015;2:e000163 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014;130:2071–104. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence , 2014. Atrial fibrillation: management. [Internet]. NICE. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180 [PubMed]

- 22. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smart NA, Waldron M, Ismail H, et al. Validation of a new tool for the assessment of study quality and reporting in exercise training studies: TESTEX. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:9–18. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hegbom F, Sire S, Heldal M, et al. Short-term exercise training in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation: effects on exercise capacity, AV conduction, and quality of life. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2006;26:24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malmo V, Nes BM, Amundsen BH, et al. Aerobic Interval Training Reduces the Burden of Atrial Fibrillation in the Short Term: A Randomized Trial. Circulation 2016;133:466–73. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osbak PS, Mourier M, Kjaer A, et al. A randomized study of the effects of exercise training on patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2011;162:1080–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pippa L, Manzoli L, Corti I, et al. Functional capacity after traditional Chinese medicine (qi gong) training in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Cardiol 2007;10:22–5. 10.1111/j.1520-037X.2007.05721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Risom SS, Zwisler AD, Rasmussen TB, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care for patients treated with catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: Results of the randomized CopenHeartRFA trial. Am Heart J 2016;181:120–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeren M, Demir R, Yigit Z, et al. Effects of inspiratory muscle training on pulmonary function, respiratory muscle strength and functional capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2016;30:1165–74. 10.1177/0269215515628038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wahlstrom M, Rydell Karlsson M, Medin J, et al. Effects of yoga in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation - a randomized controlled study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017;16:57–63. 10.1177/1474515116637734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uddin J, Zwisler AD, Lewinter C, et al. Predictors of exercise capacity following exercise-based rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease and heart failure: A meta-regression analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:683–93. 10.1177/2047487315604311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marazia S, Urso L, Contini M, et al. The Role of Ivabradine in Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients With Recent Coronary Artery Bypass Graft. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2015;20:547–53. 10.1177/1074248415575963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smart NA, Marwick TH. Exercise training for heart failure patients: factors affecting mortality and morbidity and predicted response to exercise training : Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 361 London, England: Academic Press Ltd-Elsevier Science LTD 24-28 OVAL RD, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mancini D, LeJemtel T, Aaronson K. Peak VO2: a simple yet enduring standard. Am Heart Assoc 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gabler NB, French B, Strom BL, et al. Validation of 6-minute walk distance as a surrogate end point in pulmonary arterial hypertension trials. Circulation 2012;126:349–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aliot E, Botto GL, Crijns HJ, et al. Quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: how to assess it and how to improve it. Europace 2014;16:787–96. 10.1093/europace/eut369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boden-Albala B, Litwak E, Elkind MS, et al. Social isolation and outcomes post stroke. Neurology 2005;64:1888–92. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163510.79351.AF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinberg BA, Kim S, Thomas L, et al. Increased Heart Rate Is Associated With Higher Mortality in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (AF): Results From the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of AF (ORBIT-AF). J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e002031 10.1161/JAHA.115.002031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holmqvist F, Kim S, Steinberg BA, et al. Heart rate is associated with progression of atrial fibrillation, independent of rhythm. Heart 2015;101:894–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. De Schryver N, Scavée C, Marchandise S, et al. Predictive value of the heart rate reserve in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation treated according to a strict rate-control strategy. Europace 2014;16:1125–30. 10.1093/europace/euu033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1363–73. 10.1056/NEJMoa1001337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Trulock KM, Narayan SM, Piccini JP. Rhythm control in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation: contemporary challenges including the role of ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:710–21. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang G, Parikh PB, Malhotra A, et al. Relation of body mass index and gender to left atrial size and atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:218–22. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Delgado V, Bax JJ. Diastolic dysfunction and atrial fibrillation. Heart 2015;101:1263–4. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tiwari S, Schirmer H, Jacobsen BK, et al. Association between diastolic dysfunction and future atrial fibrillation in the Tromsø Study from 1994 to 2010. Heart 2015;101:1302–8. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2018-000880supp001.docx (275.5KB, docx)