Abstract

Objectives

Musculoskeletal injuries (MSI) are an important concern in military populations. The purpose of this study was to describe the burden of MSI and associated financial cost, in a sample of US Air Force Special Operations Command Special Tactics Operators.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, medical records of the Operators were reviewed during the years 2014–2015. MSI that occurred during a 1-year period prior to the date of review were described. MSI attributes described included incidence, anatomic location, cause, activity when MSI occurred, type and lifetime cost of MSI estimated using the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System.

Results

A total of 130 Operators participated in the study (age: 29.1±5.2 years). The 1-year cumulative incidence of MSI was 49.2 injured Operators/100 Operators/year. The most frequent anatomic location and sublocation for MSI were the lower extremity (40.9% of MSI) and shoulder (20.9%), respectively. Lifting was a common cause of MSI (21.8%). A large per cent of MSI (55.5%) occurred while Operators were engaged in either physical or tactical training. Common MSI types were pain/spasm/ache (44.5%). Many MSI (41.8%) were classified as potentially preventable by an injury prevention training programme. The total lifetime cost of these MSI was estimated to be approximately US$1.2 million.

Conclusion

MSI are an important cause of morbidity and financial cost in this sample of Air Force Special Tactics Operators. There is a need to develop a customised injury prevention programme to reduce the burden and cost of MSI in this population.

Keywords: epidemiology, injuries, public Health, sports medicine

What are the key new findings of this study?

Musculoskeletal injuries are an important cause of morbidity and financial cost among US Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) Special Tactics (ST) Operators.

A significant proportion of these injuries were identified as being potentially preventable by an injury prevention training programme.

Musculoskeletal injuries among AFSOC ST Operators most frequently affected the shoulder and lumbopelvic spine, and the most common activity resulting in injuries was physical training.

Common injury types were pain/spasm/ache, sprain, strain and tendonitis/tenosynovitis/tendinopathy.

How might this study impact clinical practice in the future?

Finding from this research study suggest that prevention of injuries to the shoulder and lumbopelvic spine needs continued attention.

Continued focus on the utilisation of proper lifting and training techniques in this population may reduce lifting-associated injury risk during physical training as well as during job-relevant tasks, by improving ergonomics.

There is a need to develop a customised injury prevention programme to reduce the burden and cost of musculoskeletal injuries in this population.

Introduction

Military personnel participate in physical activity to improve physical fitness. Musculoskeletal injuries (MSI) are an unfortunate consequence of physical activity, including military training1 2 and sports.3 4 MSI are an important concern in military populations,5–7 including Special Operations Forces,8–10 and can result in pain and morbidity,11 healthcare utilisation,6 loss of tactical readiness,5 12 disability,13 financial cost14–16 and attrition from the military.17

The Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) is the Air Force component of the US Special Operations Command. AFSOC Special Tactics (ST) Operators are a distinct group of Operators who maintain a high level of tactical readiness for their unique mission set, which includes airfield/environmental reconnaissance and personnel recovery.18 The elite AFSOC ST Operators are exposed to unique occupational demands, which include jumping from aircraft (static line, water/land), deploying into hostile territory to secure assault and landing zones, and defending and saving injured personnel in any environment. These occupational demands place AFSOC ST Operators at high risk for sustaining MSI. Previous studies have described MSI among Air Force basic military trainees.19–21 MSI frequency was high but varied (injury visits incidence of 615.6 and 1067/1000 male and female cadets, respectively,20 and injury rates of 27.8 and 63.0/1000 person-weeks, among men and women recruits, respectively).21

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have described the burden of MSI among AFSOC ST Operators. It is important to understand the frequency and pattern of MSI in elite AFSOC ST Operators who have unique occupational demands that expose them to the risk of MSI that are different from other military and Special Operations personnel. Also, very few studies among military populations have analysed the financial cost of MSI. The purpose of this study was to describe MSI and the associated financial cost among a sample of AFSOC ST Operators.

Methods

Study participants

This epidemiology study was conducted as a part of a comprehensive injury prevention and performance optimisation study at the US Air Force 24th Special Operations Wing, Hurlburt Field, Florida, USA. AFSOC ST Operators between the ages of 18 and 55 years, with no medical or musculoskeletal conditions that prevented active duty status, were invited to participate in the study. Medical record reviewed MSI data were available for 130 male Operators. Study participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Medical record review and operational definition of MSI

Trained certified athletic trainers reviewed medical records contained in the Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application (AHLTA) during the years 2014–2015. Data about MSI were extracted.

An MSI was defined as an injury to the musculoskeletal system (bones, ligaments, muscles, tendons, etc) for which medical care was sought and was recorded in the participant’s record in AHLTA. Preventable MSI were defined as those that could be potentially prevented through injury prevention training programmes designed to improve neuromuscular, musculoskeletal and physiological characteristics related to the risk of MSI. This definition was consistent with the operational definition for MSI used by our group in previous research among US Special Forces populations.8 10

Data analysis

Data analysis included a description of MSI that occurred during a period of 1 year prior to the date of medical record review. MSI attributes included in the description were frequency and incidence, anatomic location and sublocation, cause, activity when MSI occurred and type. Potentially preventable MSI, which were a subset of all MSI, were described separately. MSI frequency was defined as the number of MSI/100 Operators/year, and MSI incidence was defined as the number of injured Operators/100 Operators/year. Statistical analysis consisted of calculation of relative frequency (percent) of MSI in each category.

Cost of MSI

Lifetime cost (sum of medical and work loss cost) of each MSI was estimated using the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System Cost of Injury Reports.22 Cost estimates were expressed in year 2013 prices, which was the latest index year available in the query system. Since the cost of goods and services are expected to increase each year due to inflation, the Bureau of Labour Statistics Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator23 was used to calculate the cost of MSI if they were to occur in the current year (2018).

Results

Medical record review was conducted for 130 Operators (age: 29.1±5.2 years). A total of 110 MSI were recorded during a 1-year period, of which 46 (41.8%) were preventable MSI. Of the 130 Operators, 34 Operators (26.2%) had one MSI, 16 Operators (12.3%) had two, 12 (9.2%) had three and two (1.5%) had four MSI in their medical records during a 1-year period. The remaining 66 Operators (50.8%) had no MSI in their medical records during a 1-year period. When data were limited to preventable MSI, 26 Operators (20.0%) had one preventable MSI, two Operators (1.5%) had two, four (3.1%) had three and one (0.8%) had four preventable MSI in their medical records during a 1-year period. The remaining 97 Operators (74.6%) had no preventable MSI in their medical records during a 1-year period.

MSI frequency was 84.6 MSI/100 Operators/year, and the incidence was 49.2 injured Operators/100 Operators/year. When preventable MSI were considered, the frequency was 35.4 MSI/100 Operators/year, and the incidence was 25.4 injured Operators/100 Operators/year.

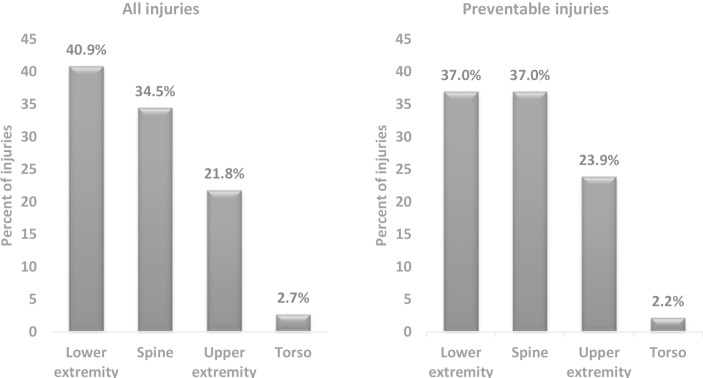

Figure 1 includes a description of anatomic location of MSI. The most frequent anatomic location was the lower extremity (40.9% of MSI), followed by the spine (34.5%). The most frequent locations for preventable MSI also were the lower extremity and the spine (each 37.0%).

Figure 1.

Anatomic location of medical record reviewed musculoskeletal injuries among 130 US Air Force Special Operations Command Special Tactics Operators (during a 1-year period).

Anatomic sublocations of MSI are described in table 1. Frequent anatomic sublocations were the shoulder (20.9%) and lumbopelvic spine (15.5%). Preventable MSI frequently affected the shoulder and the thoracic spine (each 21.7%).

Table 1.

Anatomic sublocation of medical record reviewed musculoskeletal injuries among 130 US Air Force Special Operations Command Special Tactics Operators (during a 1-year period)

| Injury anatomic location | Injury anatomic sublocation | All injuries (%) | Preventable injuries (%) |

| Lower extremity | Hip | 7 (6.4) | 2 (4.3) |

| Knee | 16 (14.5) | 7 (15.2) | |

| Ankle | 12 (10.9) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Lower leg | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | |

| Foot and toes | 7 (6.4) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Upper extremity | Shoulder | 23 (20.9) | 10 (21.7) |

| Elbow | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) | |

| Spine | Cervical | 8 (7.3) | 1 (2.2) |

| Thoracic | 13 (11.8) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Lumbo-pelvic | 17 (15.5) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Torso | Abdomen | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Chest | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total | 110 | 46 | |

As seen in table 2, lifting was the most common cause of MSI (21.8%), followed by direct trauma and landing (each 8.2%). Medical records did not contain information about the cause of a large percent (31.8%) of MSI. The most common causes of preventable MSI were lifting (47.8%) and ruck marching (13.0%). The majority of lifting-associated MSI (all: 91.7%, preventable: 90.9%) occurred during weight lifting as a part of physical training (PT).

Table 2.

Cause of medical record reviewed musculoskeletal injuries among 130 US Air Force Special Operations Command Special Tactics Operators (during a 1-year period)

| Cause of injury | All injuries (%) | Preventable injuries (%) |

| Crushing | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Direct trauma | 9 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fall—same level | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fall—stairs or ladder | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Landing | 9 (8.2) | 2 (4.3) |

| Lifting | 24 (21.8) | 22 (47.8) |

| Planting | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pulling | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) |

| Ruck marching | 6 (5.5) | 6 (13.0) |

| Running | 3 (2.7) | 3 (6.5) |

| Twist/turn/slip (no fall) | 3 (2.7) | 1 (2.2) |

| Other | 14 (12.7) | 8 (17.4) |

| Unknown | 35 (31.8) | 3 (6.5) |

| Total | 110 | 46 |

Table 3 lists the activities Operators were participating in when MSI occurred. The most common activity resulting in MSI was PT (38.2%), followed by tactical training (17.3%). Data about activity was missing for a large percent (24.5%) of MSI. Similarly, PT was the most common activity (65.2%), followed by tactical training (TT, 13.0%) for preventable MSI.

Table 3.

Activity when musculoskeletal injury occurred among 130 US Air Force Special Operations Command Special Tactics Operators (during a 1-year period)

| Activity | All injuries (%) | Preventable injuries (%) |

| Physical training | 42 (38.2) | 30 (65.2) |

| Tactical training | 19 (17.3) | 6 (13.0) |

| Recreational activity/sports | 9 (8.2) | 3 (6.5) |

| Combat | 5 (4.5) | 2 (4.3) |

| Occupational tasks | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Other | 7 (6.4) | 4 (8.7) |

| Unknown | 27 (24.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 110 | 46 |

MSI types are listed in table 4. A large percent (44.5%) of MSI were diagnosed as pain/spasm/ache in the medical records, without further elucidation of pathology. Less common MSI were sprain, strain and tendonitis/tenosynovitis/tendinopathy (each 11.8%). Among preventable MSI, the most frequent type also was pain/spasm/ache (39.1%), followed by tendonitis /tenosynovitis/tendinopathy (21.7%).

Table 4.

Type of musculoskeletal injuries among 130 US Air Force Special Operations Command Special Tactics Operators (during a 1-year period)

| Injury type | All injuries (%) | Preventable injuries (%) |

| Chondromalacia/ patellofemoral pain | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Disc injury | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fracture | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Impingement | 6 (5.5) | 1 (2.2) |

| Labral tear | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) |

| Lateral epicondylitis | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Meniscal | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Nerve | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pain/spasm/ache | 49 (44.5) | 18 (39.1) |

| Plantar fasciitis | 2 (1.8) | 2 (4.3) |

| Shin splints | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sprain | 13 (11.8) | 3 (6.5) |

| Strain | 13 (11.8) | 8 (17.4) |

| Tendonitis/tenosynovitis/ tendinopathy | 13 (11.8) | 10 (21.7) |

| Other | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 110 | 46 |

The total lifetime cost of these MSI among 130 active duty AFSOC ST Operators during a 1-year period, which included medical costs and work loss costs combined, was estimated to be approximately US$1.2 million in 2018. Of this, the total lifetime cost of preventable MSI was around US$440 000.

Discussion

The purpose of this analysis was to describe MSI and the associated financial cost in a sample of 130 AFSOC ST Operators.

MSI incidence

The 1-year cumulative incidence of MSI was 49.2 injured Operators/100 Operators/year, and MSI frequency was 84.6 MSI/100 Operators per year. No previous studies have described the epidemiology of MSI among AFSOC ST Operators, but studies have described injury rates among Air Force active duty personnel6 24 and trainees.19–21 In general, the rate of injuries reported among Air Force trainees was higher than that reported in the current study among Operators and in other studies among active duty Air Force personnel.6 24 Billings et al described the injury burden among US Air Force cadets, reporting the frequency of all injury visits was approximately 103/week/1000 male cadets.20 This frequency was much higher than that estimated in the current study (about 16/week/1000 Operators). Similarly, Snedecor et al reported a higher injury rate in male US Air Force recruits than that in the current study (27.8/1000 person-weeks vs 16/week/1000 Operators).21 Previous studies among military trainees have reported very high frequency of injuries during Army Basic Training,25 Marine Corps boot camp26 and in Navy recruits.27 Military trainees undergo intense physical conditioning during a relatively short period of time, resulting in high rates of injuries. In contrast, Nye et al described a much lower rate of injuries among Air Force basic military trainees (15.1 injuries/1000 person-weeks among male cadets).19 The data for the study by Nye et al was collected in 2012–2014, while data for the Billing et al and Snedecor et al studies were collected in 2002 and 1994–1995, respectively. Nye et al cautiously explained that this reduced rate of injuries may reflect a true decline of injury rates among Air Force basic trainees in the USA.

Eaton et al reviewed non-battle injuries during deployment among active duty Air Force personnel24 and reported an incidence of 97.49/1000 person-years,24 which was lower than the injury rate reported in the current study. Jones et al reported an injury rate of approximately 1500/1000 person-years among non-deployed active duty Air Force personnel during the period 2000–2006,6 which is higher than that reported in the current study. The differences in injury incidence reported across studies may have occurred due to differences in the study populations and occupational demands (AFSOC ST Operators compared with all Air Force personnel), incompleteness of MSI data during deployment, differing sources of MSI data (various databases, medical data collected on-site during deployment) and differing access to healthcare in the operational unit’s compound. A larger sample of ST Operators with collection of data over longer periods of time could provide better understanding of the reasons for these differences.

Few epidemiology studies in military populations have included an analysis of potentially preventable MSI. In the current study, potentially preventable MSI accounted for a considerable percent (42%) of MSI. Analyses conducted previously by our group have revealed that a large proportion of MSI among Special Forces personnel are potentially preventable (Naval Special Warfare (NSW) Operators and students — 40% of MSI8 and US Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) Operators — 77%).10 There is a need to develop a customised injury prevention programme to mitigate the risk of MSI in these populations.

Anatomic location of MSI

The most frequent anatomic location for MSI in the current study was the lower extremity (41%). The lower extremity was reported as the most frequent location of MSI among US Air Force trainees.19 Previous studies have not described the anatomic location of MSI among AFSOC ST Operators, and studies in other populations have often utilised different methods for classification of anatomic locations. The lower extremity has been reported to be the most common location for MSI among other Special Operations Forces (NSW Sea, Air and Land (SEAL) Qualification Training (SQT) students: 65% to >75%8 28; Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewman (SWCC) Operators: 37%8; Crewman Qualification Training (CQT) students: 64%8; Marines Corps Special Operations Company: 46%29 and USASOC Operators: 50%.10 The shoulder was the most commonly injured sublocation (21% of MSI) in the current study. This finding agrees with previous research in USASOC Operators, where the shoulder and knee were the most common sublocation for MSI (each 23% of injuries)10 and among NSW SEAL Operators (22%).8

In the current study, potentially preventable MSI most commonly affected the shoulder and thoracic spine (each 22% of preventable MSI). This is in partial agreement with findings among USASOC Operators, where preventable MSI most commonly affected the shoulder and knee (each 25%).10 The knee (15%) was the third most common sublocation for preventable MSI in the current study. AFSOC ST Operators have specific job demands, including prolonged exposure to vibration on aircraft, that could explain the frequency of preventable MSI at the spine. A high occurrence of lower back injuries also were reported among SWCC Operators30 who are exposed to turbulence and vibration on boats. The risk factors for these MSI requires further study. The distinct pattern of MSI among AFSOC ST Operators provides evidence for injury prevention programmatic needs for this Special Operations group.

MSI causes and activities during MSI

The most frequent cause of MSI in the current study was lifting (22%) and the most common activity associated with MSI was PT (38%). Injuries during PT have been described extensively among recruits.2 8 21 31 Few studies among active duty Special Operations Forces have described MSI cause or activity during onset of MSI. Our previous research with NSW personnel showed that a large percent of injuries occurred during PT/TT among NSW SEAL Operators (PT: 28%, TT 11%), SQT students (68%, 10%), SWCC Operators (35%, 17%) and CQT students (39%, 12%).8 PT previously has been identified as an important cause of MSI among other military personnel, as well.1 2 This could indicate a need for modification or education on PT techniques.

In the current study, lifting was the most frequent cause of injury among AFSOC ST Operators. This finding is in agreement with research among NSW personnel, where lifting was the most common cause of injury among NSW SEAL (14%) and SWCC Operators (17%).8 Continued focus on the utilisation of proper lifting and training techniques in this population may reduce injury risk during PT as well as during job-relevant tasks by improving ergonomics.

MSI types

Pain/spasm/ache, without further elucidation of pathology, was overwhelmingly the most common injury type (45%) in the current study, followed by sprain, strain and tendonitis/tenosynovitis/tendinopathy (each 12%). In Air Force personnel, sprains and strains (53%) have been identified as the most frequent types of non-battle injuries during deployment,24 while inflammation and pain (60%) followed by sprains, strains and ruptures (31%) were most common in trainees.19 Previous research with NSW personnel found pain/spasm/ache was the most common injury type in Operators (NSW SEAL Operators: 30% of MSI, and SWCC Operators: 22%), while tendonitis/tenosynovitis/tendinopathy (21%) was most common in SQT students and tendonitis/tenosynovitis/tendinopathy and fracture (each 15%) among CQT students.8 Among USASOC Operators, the most common injury types was sprain (23%).10

The differences in MSI types between these studies are probably due to differences in physical and occupational demands between various groups of military personnel (ie, lifting among AFSOC ST Operators, exposure to vibration among SWCC Operators) and differences in sources of data (ie, various databases, International Classification of Diseases coded MSI data). Despite variation in MSI types among different studies, in general, relatively minor MSI (ie, pain/spasm/ache, strain, sprain) were frequent. Injury prevention programme specifically designed for these MSI types could reduce risk.

Financial cost of MSI

The cost of MSI that occurred among 130 AFSOC ST Operators during a 1-year period was estimated to be around US$1.2 million in 2018, with a considerable amount (US$440 000) due to MSI that were potentially preventable. During an 2-year period, injuries sustained by Air Force trainees in a study by Nye et al resulted in more than US$43.7 million per year in medical and non-medical costs.19 Nye and de la Motte recommended that a 10% decrease in medical attrition of training pipeline students could create over US$2.5 million annually in savings.32 Further research is needed to examine costs of MSI for operational units like AFSOC ST. Culturally, specific injury prevention programme may reduce injury risk, which, in turn, would result in a reduction in both direct and indirect medical costs.

Study limitations

Medical records were used as the source of MSI data in the current study. Medical record review may underestimate the true incidence of MSI if medical care was not sought, which is known to be common among military personnel.31 33 Estimation of direct and indirect financial cost of MSI does not include the cost of training a replacement for highly trained military personnel (such as AFSOC ST Operators), which has been estimated to exceed US$1 000 000.16 AFSOC ST Operators are a highly specialised Special Operations group; therefore the results of this study may not be generalisable to other military personnel.

Conclusion

The results of this descriptive epidemiology study of MSI among AFSOC ST Operators highlight several interesting areas of concern. MSI were an important cause of morbidity in this sample of Operators. MSI incidence calculated in this study was higher than that reported in previous research in active duty Special Operations Forces Operators, identifying AFSOC ST Operators as a high-risk group for MSI. There is a need to develop a customised injury prevention programme to reduce the frequency of MSI in this population, especially to address injuries to the lower extremities and shoulder, that occur during PT/TT. The lifetime costs of MSI, among 130 Operators across a 1-year span, was calculated to be approximately US$1.2 million, providing a financial rationale for identifying and mitigating the specific causes of these MSI. Training is easily modifiable and has been consistently reported as a high-risk activity for Special Operations Forces Operators. Therefore, future research should also focus on identifying the modifiable components of AFSOC ST Operators’ training that precipitate MSI.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the AFSOC ST Operators who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML contributed to study design. ML, CDJ and KAK contributed to data analysis. ML and MFW contributed to data collection. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation.

Funding: This work was supported by AFMC/AFRL FA86501226271. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense, US Air Force, or US Air Force Special Operations Command.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The project was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh (PRO11090785: AFSOC Injury Prevention/Performance Optimization) and the Research Oversight and Compliance Division of the Department of Air Force (FWR20120207X: AFSOC Injury Prevention/Performance Optimization). Written informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Roy TC, Piva SR, Christiansen BC, et al. . Description of musculoskeletal injuries occurring in female soldiers deployed to Afghanistan. Mil Med 2015;180:269–75. 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaufman KR, Brodine S, Shaffer R. Military training-related injuries: surveillance, research, and prevention. Am J Prev Med 2000;18 54–63. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00114-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sammito S, Gundlach N, Böckelmann I. Injuries caused during military duty and leisure sport activity. Work 2016;54:121–6. 10.3233/WOR-162294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cameron KL, Owens BD. The burden and management of sports-related musculoskeletal injuries and conditions within the US military. Clin Sports Med 2014;33:573–89. 10.1016/j.csm.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hauret KG, Jones BH, Bullock SH, et al. . Musculoskeletal injuries description of an under-recognized injury problem among military personnel. Am J Prev Med 2010;38 S61–70. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones BH, Canham-Chervak M, Canada S. Medical surveillance of injuries in the u.S. Military. Descriptive epidemiology and recommendations for improvement. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:42–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lovalekar MT, Abt JP, Sell TC, et al. . Descriptive epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries in the army 101st airborne (air assault) division. Mil Med 2016;181:900–6. 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lovalekar M, Perlsweig KA, Keenan KA, et al. . Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries sustained by naval special forces operators and students. J Sci Med Sport 2017;20 S51–56. 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peterson SN, Call MH, Wood DE, et al. . Injuries in naval special warfare sea, air, and land personnel: epidemiology and surgical management. Oper Tech Sports Med 2005;13:131–5. 10.1053/j.otsm.2005.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abt JP, Sell TC, Lovalekar MT, et al. . Injury epidemiology of U.S. Army special operations forces. Mil Med 2014;179:1106–12. 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seay JF, Shing T, Wilburn K. Lower extremity injury increases risk of first-time low back pain in the U.S. Army. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harman DR, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD. Aeromedical evacuations from operation Iraqi Freedom: a descriptive study. Mil Med 2005;170:521–7. 10.7205/MILMED.170.6.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Songer TJ, LaPorte RE. Disabilities due to injury in the military. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:33–40. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00107-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fabrizio AJ. Work-related upper extremity injuries: prevalence, cost and risk factors in military and civilian populations. Work 2002;18:115–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones BH, Canham-Chervak M, Sleet DA. An evidence-based public health approach to injury priorities and prevention recommendations for the u.s. Military. Am J Prev Med 2010;38 S1–10. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen SP, Griffith S, Larkin TM, et al. . Presentation, diagnoses, mechanisms of injury, and treatment of soldiers injured in Operation Iraqi freedom: an epidemiological study conducted at two military pain management centers. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1098–103. 10.1213/01.ane.0000169332.45209.cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwartz O, Levinson T, Astman N, et al. . Attrition due to orthopedic reasons during combat training: rates, types of injuries, and comparison between infantry and noninfantry units. Mil Med 2014;179:897–900. 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Air force special tactics 24th Special Operations Wing , 2018. Available from: http://www.24sow.af.mil/ [Accessed 4 Feb 2018].

- 19. Nye NS, Pawlak MT, Webber BJ, et al. . Description and rate of musculoskeletal injuries in air force basic military trainees, 2012-2014. J Athl Train 2016;51:858–65. 10.4085/1062-6050-51.10.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Billings CE. Epidemiology of injuries and illnesses during the United States air force academy 2002 basic cadet training program: documenting the need for prevention. Mil Med 2004;169:664–70. 10.7205/MILMED.169.8.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snedecor MR, Boudreau CF, Ellis BE, et al. . U.S. Air force recruit injury and health study. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:129–40. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Center for disease control and prevention (cdc) web-based injury statistics query and reporting system cost of injury online query system , 2017. Available from: https://wisqars.cdc.gov:8443/costT/ [Accessed 12 Mar 2017].

- 23. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator , 2018. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm [Accessed 15 Apr 2018].

- 24. Eaton M, Marshall SW, Fujimoto S, et al. . Review of non-battle injuries in air force personnel deployed in support of operation enduring freedom and operation iraqi freedom. Mil Med 2011;176:1007–14. 10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bell NS, Mangione TW, Hemenway D, et al. . High injury rates among female army trainees: a function of gender? Am J Prev Med 2000;18:141–6. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00173-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Almeida SA, Williams KM, Shaffer RA, et al. . Epidemiological patterns of musculoskeletal injuries and physical training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;31:1176–82. 10.1097/00005768-199908000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kelly EW, Bradway LF. A team approach to the treatment of musculoskeletal injuries suffered by Navy recruits: a method to decrease attrition and improve quality of care. Mil Med 1997;162:354–9. 10.1093/milmed/162.5.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Linenger JM, Flinn S, Thomas B, et al. . Musculoskeletal and medical morbidity associated with rigorous physical training. Clin J Sport Med 1993;3:229–34. 10.1097/00042752-199310000-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hollingsworth DJ. The prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal injuries during a pre-deployment workup cycle: survey of a marine corps special operations company. J Spec Oper Med 2009;9:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ensign W, Hodgdon JA, Prusaczyk WK. A survey of self-reported injuries among special boat operators. Naval health research center: San Diego, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shwayhat AF, Linenger JM, Hofherr LK, et al. . Profiles of exercise history and overuse injuries among United States Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) recruits. Am J Sports Med 1994;22:835–40. 10.1177/036354659402200616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nye NS, de la Motte SJ. Rationale for embedded musculoskeletal care in air force training and operational units. J Athl Train 2016;51:846–8. 10.4085/1062-6050.51.5.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lynch JH, Pallis MP. Clinical diagnoses in a special forces group: the musculoskeletal burden. J Special Oper Med 2008;8:76–80. [Google Scholar]