Abstract

Background: MiR-146b has been reported to be overexpressed in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) tissues and associated with aggressive PTC. MiR-146b is regarded as a relevant diagnostic marker for this type of cancer. MiR-146b-5p has been confirmed to increase cell proliferation by repressing SMAD4. However, detailed functional analysis of another mature form of miR-146b, miR-146b-3p, has not been carried out. This study aimed to identify the differential expression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in more aggressive PTC associated with lymph node metastasis, and further elucidate the contribution and mechanism of miR-146b-3p in the process of PTC metastasis.

Methods: Expression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p was assessed in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples from PTC patients, and the relationship with lymph node metastasis was analyzed. A variety of PTC cells, including BHP10-3, BHP10-3SCmice, and K1 cells, were cultured and treated with miR-146b-5p or miR-146b-3p mimics/inhibitors. The cell migration and invasion abilities were characterized by the real-time cell analyzer assay and Transwell™ assay. PTC xenograft models were used to examine the effect of miR-146b-3p on PTC metastatic ability in vivo. Direct downstream targets of miR-146b-3p were analyzed by luciferase reporter assay and Western blotting. The mechanism by which miR-146b-3p affects cell metastasis was further characterized by co-transfection with merlin, the protein product of the NF2 gene.

Results: MiR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression was significantly higher in thyroid cancer tissues and cell lines than in normal thyroid tissue and cells. Moreover, expression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p was further increased in thyroid metastatic nodes than in thyroid cancer. After overexpression of miR-146b-5p or miR-146b-3p in BHP10-3 or K1 cells, PTC migration and invasion were increased. Notably, miR-146b-3p increased cell migration and invasion more obviously than did miR-146b-5p. Overexpression of miR-146b-3p also significantly promoted PTC tumor metastasis in vivo. Luciferase reporter assay results revealed that NF2 is a downstream target of miR-146b-3p in PTC cells, as miR-146b-3p bound directly to the 3′ untranslated region of NF2, thus reducing protein levels of NF2. Overexpression of merlin reversed the enhanced aggressive effects of miR-146b-3p.

Conclusions: Overexpression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p is associated with PTC metastasis. MiR-146b-3p enhances cell invasion and metastasis more obviously than miR-146b-5p through the suppression of the NF2 gene. These findings suggest a potential diagnostic and therapeutic value of these miRNAs in PTC metastasis.

Keywords: PTC, miR-146b-5p, miR-146b-3p, metastasis, NF2

Introduction

Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is the most commonly diagnosed thyroid cancer, accounting for ≥80% of thyroid malignancies (1). Although PTC is usually indolent and curable with surgical thyroidectomy, a subset of patients who are not diagnosed in a timely manner will have aggressive disease characterized by local recurrence and/or distant metastasis. Therefore, the identification of patients with an aggressive phenotype is important for determining the need for adjuvant therapy and long-term follow-up monitoring.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, noncoding RNAs that negatively regulate gene expression through binding to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and by blocking the translation or degradation of the mRNAs (2). MiRNAs have been reported to be able to post-transcriptionally regulate up to a third of human genes, suggesting that miRNAs may have important roles in physiological and pathological processes, including human carcinogenesis (3). MiRNA expression is tissue specific, and dysregulation of miRNA expression has been described in a variety of tumors, including lung, liver, breast, and colorectal cancer (4,5). In thyroid cancer, the miRNA expression pattern depends on cellular origin and degree of tumor differentiation. Numerous studies have demonstrated an increased aberrant miRNA expression, including miR-146b, miR-221, and miR-222, in PTCs compared to normal thyroid tissues (6–11). Recently, further studies have reported that miRNAs such as miR-146b (12–15) are strongly associated with more aggressive PTC.

In humans, miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p are products of the same MIR146B gene that is located on chromosome 10 at position q24.32. A number of studies have examined the role of miR-146b-5p in cancer, including lung, breast, glioma, and pancreatic cancer. MiR-146b-5p was proven to decrease the migration and invasiveness of cancer cells by targeting transcripts of the MMP16 and EGFR genes and negatively regulating the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway (16–18). MiRNAs behave in a dual mode in cancer as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors, depending on tissue type and specific targets (19). Unlike in other cancers, miR-146b-5p has a confirmed oncogenic role regulating TGF-β signal transduction by repressing SMAD4 in PTC (20) and promoting metastasis by targeting ZNRF3 (21). Furthermore, miR-146b-5p has been shown to be sequentially upregulated in different stages of PTC (22,23). While miR-146b-5p is relatively well characterized, such functional studies of miR-146b-3p have rarely been performed. In a human non–small cell lung cancer study, miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p had opposite prognostic values (24), which indicated that although they are encoded by the same gene, miR-146b-3p might have a different role from miR-146b-5p and other important functions in human carcinogenesis. However, the possible roles and mechanisms of miR-146b-3p in human PTC are still not well established.

This study aimed to identify differential expression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in more aggressive forms of PTC, such as those with lymph node metastasis (LNM), and it further elucidated the contribution and mechanism of miR-146b-3p in the process of PTC metastasis. The study confirms that both miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p are overexpressed in PTC with LNM. MiR-146b-3p enhanced cell migration and invasion more obviously than did miR-146b-5p. Moreover, the NF2 gene was identified as a direct and functional target of miR-146b-3p in PTC.

Methods

Tissue samples

A total of 72 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues samples from 24 patients were obtained at the Department of Pathology in Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong University. All tissues samples were pathologically confirmed as PTC tissues, matched adjacent non-neoplastic thyroid tissues, normal lymph node tissues, or LNM tissues (Fig. 1A). The histological variants of most of tissue samples (23/24) were classical variant PTC (CV-PTC), and only one case was follicular variant PTC (FV-PTC). Detailed patient information is shown in Table 1. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital.

FIG. 1.

MiR-146b-5p and miR146b-3p expression is significantly increased in PTC tissues and further enhanced in MLN. (A) The histological changes of different thyroid tissues and LN tissues stained with H&E (magnification × 100). (B) Relative expression levels of mature miR-146b-5p (left panels) and miR-146b-3p (right panels) in 72 samples, including PTC, matched normal thyroid tissue, MLN, and LN, were determined by qRT-PCR and normalized against an endogenous control RUN6B. Data were analyzed using a ΔΔCt approach and expressed as miR-146b/RUN6B ratio (−2ΔCt[miR-146b-RUN6B]). (C) Fold change of expression of mature miR-146b-5p (left panels) and miR-146b-3p (right panels) in 14 pairs of MLN and their corresponding primary PTC. Data were analyzed using log2 fold change (ΔΔCt [MLN/each corresponding PTC]). Significant upregulation of miR-146b in paired samples was defined as log2 fold change >1, which means twofold higher. (D) Relative expression levels of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in PTC patients with different aggressive abilities (PTC with LNM [PTC-M] vs. PTC without LNM [PTC-NM]) by qRT-PCR and normalized against an endogenous control RUN6B. NT, normal thyroid tissues, PTC, papillary thyroid cancer; MLN, metastatic lymph nodes; LN, lymph node; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

Table 1.

Initial Clinicopathologic Characteristics of PTC Patients

| Clinicopathologic features | PTC with LNM | PTC without LNM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 14 | 10 | |

| Mean age, years (range) | 36 (21–57) | 50 (34–68) | 0.014 |

| Men, n (%) | 3 (21.4%) | 3 (30%) | 0.65 |

| Pathological stagea | 0.62 | ||

| I/II | 9 | 9 | |

| III/IV | 5 | 1 | |

| LN, n (range) | 21 (4–47) | 15 (7–32) | 0.22 |

| Metastatic LN, n (range) | 10 (1–39) | 0 | 0.004 |

| Mean tumor size, cm (range) | 2.3 (0.8–5.5) | 3.1 (1.8–5) | 0.11 |

Using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging for Thyroid Cancer (seventh edition, 2010).

PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; LNM, lymph node metastasis; LN, lymph node.

Cell culture

Three human PTC cell lines were cultured. BHP10-3 and BHP10-3SCmice cells were kindly provided by Dr. Gary Clayman (The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX), and K1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Xingsong Tian (Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery, Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong University, Shandong, China). For imaging analysis in vivo, high tumorigenic BHP10-3SCmice cells were stably labeled for bioluminescence and red fluorescent protein (named BHP10-3SCmluc; JiuyuJintai Biotechnology Co., Beijing, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (BHP10-3 and BHP10-3SCmice; HyClone) or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; K1; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (SAFC Bioscience, St. Louis, MO). The procedure to obtain primary normal human thyrocytes (PHT) has been carefully standardized (25,26). Briefly, normal tissue specimens were digested in 2 mg/mL collagenase I (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 0.125% trypsin for 1 h. After thyrocytes were filtered and washed, they were seeded and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (HyClone) containing 10% newborn calf serum (Gibco) and bovine thyrotropin (TSH; 2 mIU/mL; Sigma–Aldrich).

MicroRNA extraction, reverse transcription, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

MicroRNA was extracted from FFPE human tissues and human thyroid cell lines using a miRNeasy FFPE kit (BioTeke Corporation, Beijing, China) and TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) separately. MiR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p were reverse transcribed and quantified with quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using an All-in-One™ miRNA qRT-PCR Detection Kit (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD). The miRNA primers were purchased from GeneCopoeia. RUN6B was used as an endogenous control.

Plasmid construction, transfection with microRNA mimics/inhibitor, and expression constructs

Recombinant plasmids with 3′ UTRs of potential target genes (NF2 and MTSS1) based on miRbase and RNA22 information were constructed. The oligonucleotides were ligated downstream of the Renilla luciferase open reading frame in the pMIR-REPORT™ miRNA expression reporter vector (Ambion, Waltham, MA) using SacI and HindIII restriction sites. The primers and corresponding point mutation sequences used for plasmid inserts are shown in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy). Expression vector for merlin (pcDNA3 merlin) was purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA; Addgene 11623). All transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For BHP10-3 and K1 cells, microRNA mimics and negative control (miR-NC; RiboBio Co., Guangzhou, China) were used at a final concentration of 50 nM. For BHP10-3SCmice cells, microRNA inhibitor and negative control (anti-NC; RiboBio Co.) were transfected at a final concentration of 100 nM. The pcDNA3 merlin and respective empty-vector control (pcDNA3) were transfected at 4 μg per 60 mm culture dish.

Dual luciferase activity assay

For luciferase reporter activity assays, cells were seeded in 24-well plates and co-transfected with either miR-146b-3p mimics or inhibitor together with 0.5 μg/well of the constructed pMIR-REPORT™ miRNA target expression vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, luciferase activities were measured using the dual luciferase reporter assay system kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions using a LB942 luminescence reader (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Values were double normalized to firefly luciferase activity and to cells transfected with empty pMIR-REPORT™ control vectors.

Real-time cell analyzer migration and invasion assays

Real-time cell analyzer (RTCA) migration and invasion assay measures the effect of any treatment in a real-time setting (27). For RTCA migration or invasion experiments, transfections were performed as described above. Cells were then starved in serum-free medium for 12 h and seeded in RTCA CIM-16 plate (xCELLigence Roche, Penzberg, Germany) in serum-free medium. Full growth medium was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. For invasion assays, the CIM-16 plates were initially coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) diluted in serum-free medium at a ratio of 1:40. Real-time measurements were performed at 96 h for invasion assays or 24 h for migration assays using the RTCA device (xCELLigence Roche).

Transwell™ migration and invasion assays

For Transwell™ migration and invasion experiments, cells were starved in serum-free medium for 12 h after transfection and seeded on 24-well Transwell™ plates with a polycarbonate membrane and an 8 μm pore size (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY) in serum-free medium. Full growth medium was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. For invasion assays, the 24-well Transwell™ plates were initially coated with Matrigel diluted in serum-free medium at a ratio of 1:30. After 24 or 48 h, respectively, for the migration or invasion assays, cells remaining in the upper chamber or on the upper membrane were carefully removed. Cells adhering to the lower membrane were stained with hematoxylin and imaged using a Zeiss A2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The number of cells was counted using ImageJ.

Animal studies

The animal experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital. Fifteen male BALB/c nude mice (four weeks old) were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China) and acclimated to the specific pathogen-free standard housing conditions for one week. For the establishment of the PTC xenograft model, BHP10-3SCmluc cells were suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 2 × 107/mL with a volume of 250 μL and inoculated intramuscularly into the left leg of nude mice. As shown in Figure 5A, after two weeks, mice were imaged for bioluminescence in vivo to exclude any that were not successfully xenografted. The successfully xenografted nude mice were randomly divided into two groups: hsa-miR-146b-3p mimics (miR-146b-3p agomir) or agomir Ncontrol (NC agomir; RiboBio Co.) were directly injected into the implanted tumor at the dose of 2.5 nmol in 100 μL PBS per mouse twice per week for a total of eight times. Tumor and metastasis bioluminescent imaging in vivo was analyzed weekly. Animals were sacrificed at the end of the sixth week after xenografting, and ectopic implanted tumors, metastasis tumor tissues, or lymph nodes were collected for further fluorescent imaging ex vivo, histopathology, and Western blotting analysis.

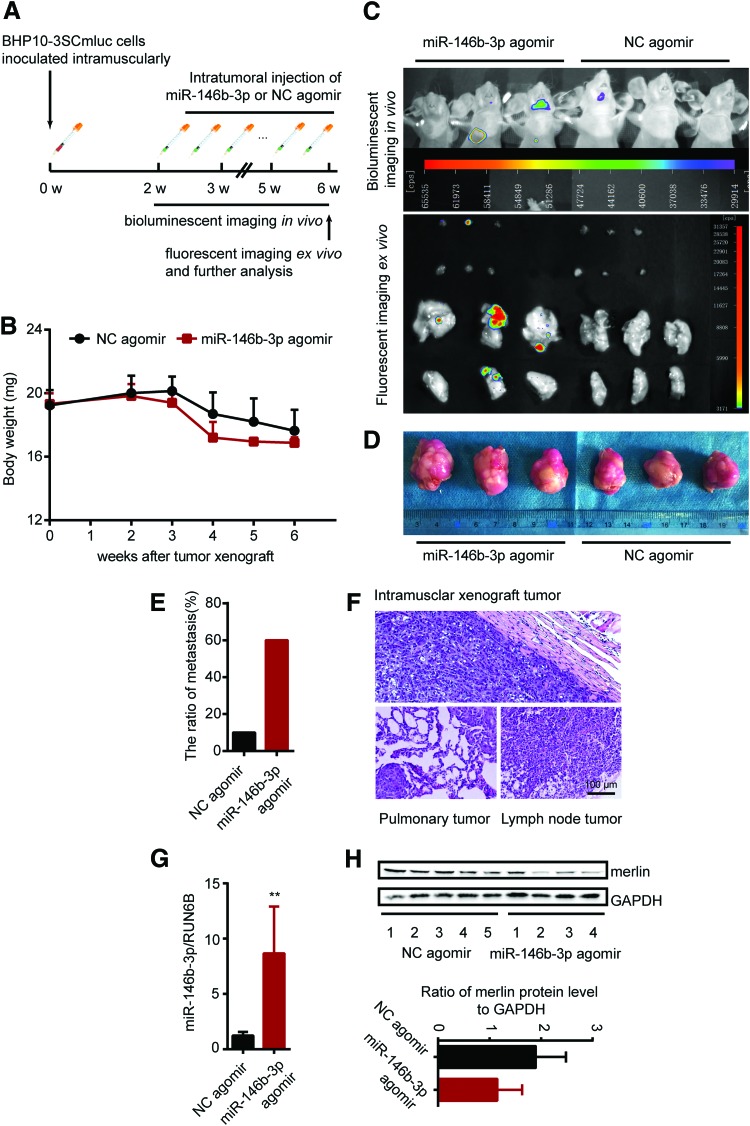

FIG. 5.

MiR-146b-3p promotes tumor metastasis in vivo. (A) Schematic of male BALB/c PTC intramuscular xenograft nude mice model. (B) Body weight of miR-146b-3p agomir or NC agomir (control) treated BHP10-3SCmluc inoculated nude mice (n = 5, 10). (C) For spontaneous tumor metastasis images were taken from three representative miR-146b-3p agomir or NC agomir (control) treated model separately. Bioluminescence images were obtained from the chest side of the mice in vivo (upper), and fluorescence images were obtained from the lungs and lymph nodes of sacrificed mice ex vivo (lower) at the end time point. (D) The size and morphology of the miR-146b-3p agomir or NC agomir treated BHP10-3SCmluc xenografts in nude mice. (E) Ratio of metastasis of miR-146b-3p agomir or NC agomir (control) treated BHP10-3SCmluc inoculated nude mice. (F) Histopathological characteristics of a representative intramuscular xenograft tumor, pulmonary and lymph node metastases of sacrificed mouse stained with H&E (magnification × 100). The expression of miR-146b-3p (G) and protein levels of merlin (H) were determined by qRT-PCR and Western blot assay separately. The tissues were derived from xenograft mouse tumors treated with miR-146b-3p agomir or NC agomir. **p < 0.001. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

Bioluminescent imaging in vivo and fluorescent imaging ex vivo

To monitor the primary tumor growth and metastasis development, the LB983 NightOWL imaging system (Berthold Technologies) was used for animal imaging and analysis. For in vivo bioluminescent imaging (Luciferin), mice were anesthetized with 10 mg/mL pentobarbital in sterile water and injected intraperitoneally with 10 μL/g D-luciferin (15 mg/mL in DPBS; Promega) of body weight. Imaging was started after 10 minutes of injection. For metastasis assays, the primary tumor was covered because its bioluminescence signal was too strong. For ex vivo fluorescent imaging (red fluorescent protein [RFP]), mice lung and lymph nodes were excised, placed in the LB983 chamber, and imaged using red fluorescence.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

The tumor tissues, lung, and lymph nodes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, serially cut into sections 4 μm thick, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate the histopathology following standard procedures. Images were acquired with a Zeiss A2 microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Protein extraction and Western blotting analysis

Total proteins were extracted from cells or tissue using radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Shenergy Biocolor Bioscience & Technology Company, Shanghai, China). Total cell protein (40 μg) was electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and after incubation in 5% bovine serum albumin for one hour, the blots were probed with primary polyclonal antibody against merlin (21686-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL) at a 1:1000 dilution overnight at 4°C. GAPDH (60004-1-Ig; Proteintech) was used on the same membranes as an internal control. Detection was performed with the FluorChem Q (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows v18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), and data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between two groups were compared using an unpaired Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney's U-test. Analysis of variance was used to compare the means of multiple groups. All of the calculated p-values are two-sided. Differences were regarded as statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

MiRNA-146b expression is significantly increased in PTC tissues and further enhanced in metastatic lymph nodes

Both miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p are products of the same MIR146B gene. Studies have reported that miR-146b is overexpressed in PTC tissues and showed an association with aggressive PTC. However, these studies all focused on miR-146b-5p, while the functional role of miR-146b-3p in PTC metastasis remains elusive. This study sought to confirm that both miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression was higher in PTC tissues than in normal thyroid tissue and further enhanced in thyroid metastatic lymph nodes. The expression levels of mature miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in clinical samples (72 samples) were examined by qRT-PCR and normalized against an endogenous control (RUN6B RNA). In 14 patients with LNM (51 samples), it was found that median miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression levels were 42- and 24-fold higher, respectively, in PTC than in the non-tumorous thyroid tissues (median expression = 7.59/0.18, 12.48/0.51). Intriguingly, median miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression levels in metastatic lymph nodes were further increased (median expression = 20.94 and 42.58, respectively), while the expression levels in normal lymph nodes were very low (median expression = 0.9 and 1.31, respectively). Overall, miR-146b was significantly upregulated in metastatic lymph nodes (p < 0.05; Fig. 1B). As shown in Figure 1C, when comparing paired metastatic lymph nodes with their corresponding primary PTC tissues, in seven (50%) patients, the ratio of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p was >1.0, indicating that PTC cells with high miR-146b expression might prefer to metastasize to lymph nodes. Further, the different expression levels of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in PTC with or without LNM were analyzed. As shown in Figure 1D, median miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression levels were significantly higher in PTC with LNM than in PTC without metastasis (median miR-146b-5p expression = 7.59 and 2.22, and median miR-146b-3p expression = 12.48 and 3.48, respectively), indicating that expression levels of miR-146b positively correlate with PTC LNM.

Furthermore, the relationship between miR-146b-5p or miR-146b-3p and clinicopathologic features of PTC patients was analyzed. As Table 2 shows, the expression levels of miR-146b-3p and miR-146b-5p were significantly positively associated with LNM (p = 0.035 and 0.016, respectively). There were no significant differences in the expression levels of miR-146b-3p or miR-146b-5p based on other clinicopathologic parameters, including age at the time of diagnosis, multicentricity, and tumor staging. In addition, 7/24 PTC patients were followed for 8–10 years, and none of them had a recurrence (data not shown).

Table 2.

Correlation Analysis Between miR-146b-3p or miR-146b-5p and Clinicopathologic Features

| Clinicopathologic features | n | miR-146b-3p | p | miR-146b-5p | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of diagnosis, years | |||||

| <45 | 13 | 2.97 (0.70–47.58) | 0.543 | 2.10 (0.70–29.85) | 0.582 |

| ≥45 | 11 | 4.81 (1.09–22.17) | 2.91 (0.90–12.50) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 18 | 4.61 (0.70–47.58) | 1.000 | 2.43 (0.70–29.85) | 0.689 |

| Male | 6 | 4.94 (1.60–10.36) | 2.67 (0.73–8.33) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||

| <2 | 13 | 9.78 (2.55–47.58) | 0.046 | 6.54 (0.90–29.85) | 0.052 |

| ≥2 | 11 | 2.97 (0.66–10.36) | 1.95 (0.70–8.33) | ||

| Tumor staging (AJCC) | |||||

| I/II | 18 | 3.01 (0.66–47.58) | 0.083 | 2.05 (0.70–29.85) | 0.096 |

| III/IV | 6 | 9.99 (4.42–22.17) | 6.62 (1.95–12.50) | ||

| Number of lesions | |||||

| Single | 16 | 3.34 (0.66–22.17) | 0.126 | 2.05 (0.70–12.5) | 0.066 |

| Multiple | 8 | 10.02 (1.09–47.58) | 5.14 (1.11–29.84) | ||

| LNM | |||||

| No | 10 | 2.95 (1.09–10.36) | 0.035 | 1.61 (0.73–8.33) | 0.016 |

| Yes | 14 | 9.99 (0.66–47.58) | 5.07 (0.70–29.85) | ||

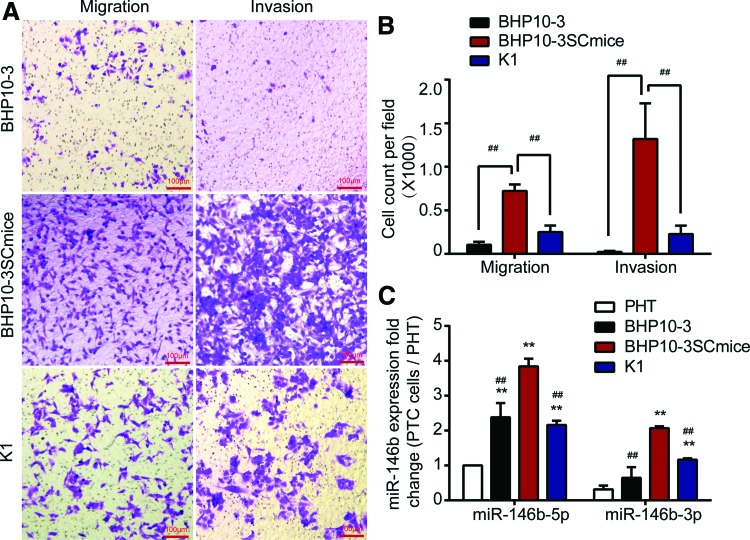

Expression of miRNA-146b is significantly increased in PTC cell lines and positively correlated with cell metastasis ability

To analyze further the role of the expression of both miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p on tumor metastasis, PHT and different PTC cell lines (K1, BHP10-3, and BHP10-3SCmice) were cultured, and cell migration and invasion abilities were analyzed. The expression of miR-146b was further assessed by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 2A and B, BHP10-3SCmice cells had the most aggressive abilities among the three PTC cell lines. Although derived from BHP10-3 cells, BHP10-3SCmice cells are extremely tumorigenic and invasive (28). Corresponding to these results, both miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression was significantly higher in PTC cell lines than in the normal human thyrocytes, and miR-146b expression was further increased in BHP10-3SCmice cells compared to BHP10-3 and K1 cells (Fig. 2C). Notably, although miR-146b-3p expression was lower than miR-146b-5p expression in the PHT and different PTC cell lines, the level of miR-146b, especially miR-146b-3p, was positively correlated with the migration and invasion abilities.

FIG. 2.

Expression of miRNA-146b is significantly increased in PTC cell lines and positively correlated with the ability of cell invasion. (A) Transwell™ assay was performed to determine the migration or invasive ability of BHP10-3, BHP10-3SC mouse and K1 cells. Representative images showed migrated or invasive cells in the lower chamber stained with hematoxylin. (B) Cell count of Transwell™ assay for above three cells was statistically analyzed. (C) Fold changes of miR-146b-5p and -3p expressions in PTC cells with different invasive abilities (BHP10-3 and BHP10-3SCmice) were calculated relative to miR-146b-5p expression in PHT by qRT-PCR and normalized against an endogenous control RUN6B. PHT, primary normal human thyrocytes. ##p < 0.005 vs. BHP10-3SCmice; **p < 0.005 vs. PHT. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

MiR-146b-3p enhances the migratory and invasive abilities more obviously than miR-146b-5p in BHP10-3 cells, and inhibiting miR-146b-3p expression can reduce the metastatic ability of BHP10-3SCmice cells

To verify the role of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in the metastasis of PTC, the migration and invasion capacities of BHP10-3 cells and K1 cells transfected with miR-146b-5p or miR-146b-3p mimics were assessed in a real-time assay using RTCA. Overexpression of miR-146b was confirmed by real-time PCR (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S1A). As indicated in Figure 3B and C, the real-time cell migratory and invasive rates of BHP10-3 cells infected with miR-146b-5p or miR-146b-3p mimics were higher than the rates in negative controls (infected with miR-NC). Furthermore, the effects of miR-146b on PTC cells were confirmed in endpoint Transwell™ assays. As shown in Figure 3D and E and Supplementary Figure S1B and C, in accordance with the RTCA assay results, increased expression of miR-146b-3p or -5p significantly enhanced the migration and invasion abilities of BHP10-3 cells and K1 cells when compared to control treatment. Notably, compared to miR-146b-5p mimics, miR-146b-3p mimics promoted migration and invasion more obviously (p < 0.005).

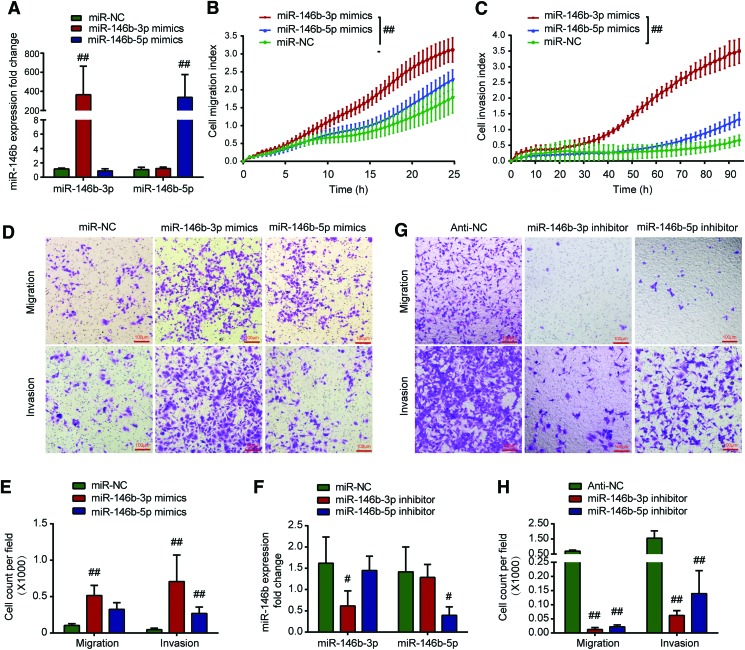

FIG. 3.

MiR-146b-3p enhances the migratory and invasive abilities more obviously than miR-146b-5p in BHP10-3 cells. Inhibiting miR-146b-3p expression can reduce the ability of metastasis in BHP10-3SC mouse cells. (A) Expression of miR-146b-5p or -3p was confirmed by real-time PCR after BHP10-3 cells were transfected with miR146b-5p mimics or -3p mimics. (B and C) BHP10-3 cells were transiently transfected with miR-146b-3p mimics (50 nM), miR-146b-5p mimics (50 nM), or negative control (miR-NC; 50 nM). Real-time measurements were performed in 24 h for the migration assay or 96 h for the invasion assay using the real-time cell analyzer system. (D) Transwell™ assay was performed to determine the migration or invasive ability of BHP10-3 cells after being transfected with miR-146b-3p mimics, miR-146b-5p mimics, or miR-NC for 24 or 48 h. Representative images showed migrated or invasive BHP10-3 cells in the lower chamber stained with hematoxylin. (E) Cell count of Transwell™ assay for the above three treatments was statistically analyzed. (F) Expression of miR-146b-5p or -3p was confirmed by real-time PCR after BHP10-3SC mouse cells were transfected with miR146b-5p inhibitor or -3p inhibitor. (G) Transwell™ assay was performed to determine the migration or invasive ability of BHP10-3SC mouse cells after transfection with miR-146b-3p inhibitor, miR-146b-5p inhibitor, or anti-NC for 24 or 48 h. Representative images show migrated or invasive BHP10-3SC mouse cells in the lower chamber stained with hematoxylin. (H) Cell count of Transwell™ assay for the above two treatments was statistically analyzed. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.005 vs. miR-NC or anti-NC. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

MiR-146b-3p or miR-146b-5p inhibitors were further used to confirm the effect of miRNA inhibitors on the PTC migratory and invasive abilities using the Transwell™ assay in BHP10-3SCmice cells, which highly express miR-146b-3p and miR-146b-5p. As shown in Figure 3F, the miR-146b inhibitor obviously decreased the expression of miR-146b in BHP10-3SCmice cells; both cell migration and invasion decreased significantly after transfection with the miR-146b inhibitor (Fig. 3G and H). Consistent with the cell transfection results with microRNA mimics, inhibition of miR-146b-3p expression reduced PTC migration and invasion more significantly than did inhibition of miR-146b-5p.

NF2 is a direct downstream target of miR-146b-3p

MicroRNAs usually exert their function by suppressing the expression of target mRNAs. Therefore, next the study searched for the target genes of miR-146b-3p in PTC. According to the prediction of miRanda (microrna.org and miRbase), RNA22 (http://cbcsrv.watson.ibm.com/rna22.html), and PITA (http://genie.weizmann.ac.il/pubs/mir07/mir07_data.html), it was found that NF2 and MTSS1 contained two predicted miR-146b-3p binding sites in their 3′ UTRs (Fig. 4A).

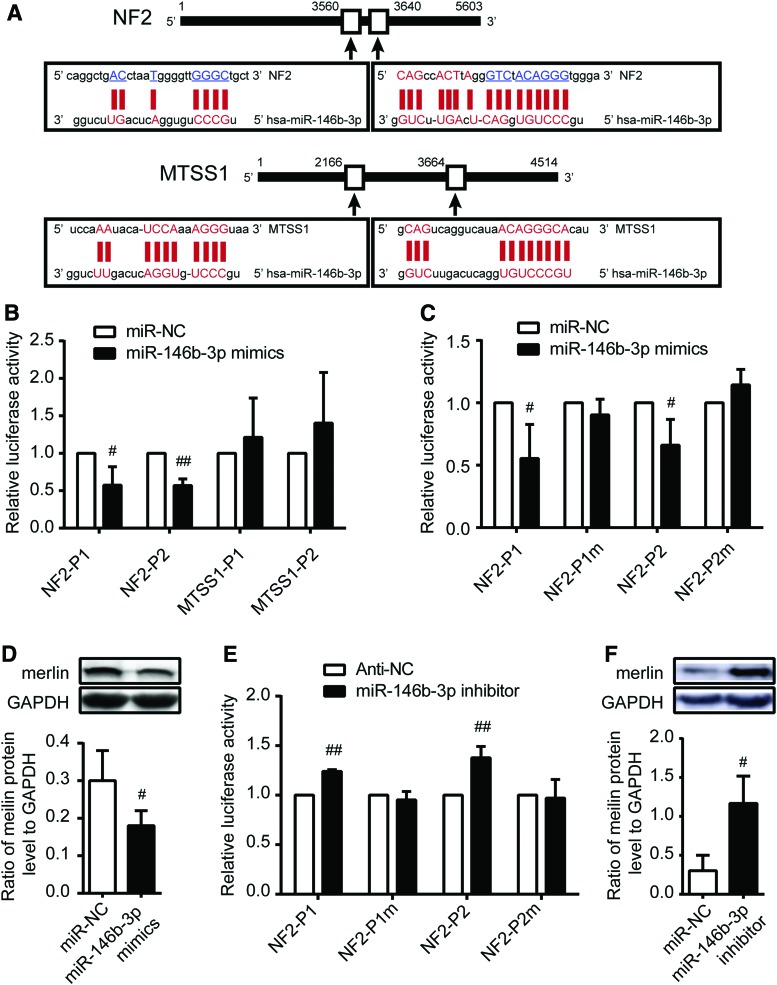

FIG. 4.

NF2 is a direct downstream target for miR-146b-3p. (A) Diagram of miR-146b-3p putative seed sequences in the 3′ UTR of candidate mRNA. Based on bioinformation software, NF2 and MTSS1 were found to contain two possible candidate miR-146b-3p binding sites on 3′ UTR separately. (B and C) Relative luciferase activity analysis in BHP10-3 cells transiently co-transfected with 3′ UTR of wild-type or mutant recombinant NF2 or MTSS1 luciferase plasmids with miR-NC or miR-146b-3p mimics. The two wild-type recombinant plasmids of NF2 (NF2-P1 and NF2-P2) and two wild-type recombinant plasmids of MTSS1 (MTSS1-P1 and MTSS1-P2) were co-transfected into cells (B). The wild type of two NF2 3′ UTR and mutant of these NF2 3′ UTR were transfected into cells (C). (D) Merlin protein expression was detected by Western blot analysis after transfection of miR-146b-3p mimics in BHP10-3 cells. (E) Relative luciferase activity analysis in BHP10-3SC mouse cells transiently co-transfected with 3′ UTR of wild-type or mutant recombinant NF2 luciferase plasmids with anti-NC or miR-146b-3p inhibitor. (F) Merlin protein expression was detected by Western blot analysis after miR-146b-3p inhibition in BHP10-3SC mouse cells. Renilla luciferase vector was used as an internal control. The relative luciferase activities of group transfected with miR-NC or anti-NC were set as 1. UTR, untranslated region. #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 vs. miR-NC or anti-NC. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

NF2 is located on human chromosome 22q12. As a tumor suppressor gene, mutations in the NF2 gene or merlin (the tumor suppressor protein encoded by the NF2 gene) inactivation have been detected in multiple human cancer types, including mesotheliomas, thyroid, breast, and prostate cancer (29–32). MTSS1, metastasis suppressor 1, which is located on human chromosome 8q24, was identified as a potential metastasis suppressor gene in bladder cancer, prostate cancer, and breast cancer (33–37) and a powerful indicator of early stage HCC development (38). To verify whether NF2 and MTSS1 are the direct targets of miR-146b-3p, the study constructed vectors containing wild-type or mutant 3′ UTRs of NF2 or MTSS1 into a luciferase receptor vector and co-transfected them with miR-146b-3p mimics or mimic controls into BHP10-3 and K1 cell lines. The transfection efficiency was normalized by co-transfection with a Renilla reporter vector. Luciferase reporter assays showed that miR-146b-3p obviously inhibits the relative luciferase activities of two wild-type NF2 3′ UTRs by approximately 36% and 43% relative to those in the mimic controls, while the luciferase activities of the MTSS1 3′ UTRs were not decreased in PTC cells (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S2A). Moreover, with two mutated NF2 3′ UTR plasmids, there was no significant difference in the relative luciferase activity between control and miR-146b-3p mimic transfections (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. S2B). In addition, the regulation of miR-146b-3p on the 3′ UTR of NF2 was further confirmed by transfection with miR-146b-3p inhibitor or control into BHP10-3SCmice cells. As Figure 4E shows, inhibition of miR-146b-3p obviously increased the relative luciferase activities of the two wild-type NF2 3′ UTRs, and mutated NF2 3′ UTR plasmids exhibited no significant change. These results suggest that miR-146b-3p could directly bind to the 3′ UTR of NF2 but not that of MTSS1.

Western blot analysis was performed to observe any changes in merlin protein expression with miR-146b-3p mimics or inhibitor transfection. As shown in Figure 4D and F and Supplementary Fig. S2C, endogenous merlin protein expression was significantly inhibited or enhanced after miR-146b-3p mimic or inhibitor transfection. Taken together, these observations indicate that NF2 is a direct downstream target of miR-146b-3p in PTC cells.

MiR-146b-3p promotes tumor metastasis in vivo

To characterize further the effect of miR-146b-3p on PTC metastatic ability in vivo, BHP10-3SCmice cells with high tumorigenicity were chosen, and they were engineered with stably labeled dual reporters of bioluminescence (luciferase) and RFP, named BHP10-3SCmluc. Next, a PTC xenograft model was established via intramuscular injection with BHP10-3SCmluc cells. Further mice were intratumorally injected with miR-146b-3p agomir and imaged.

All mice were successfully xenografted. As shown in Figure 5B, with the prolongation of feeding time, the body weight of the mice decreased gradually. Although mice in the miR-146b-3p agomir-treated group had lower body weights than those in the control group (NC agomir-treated), the difference was not statistically significant. Tumor metastasis was detected by in vivo bioluminescence imaging weekly. On the fifth week after xenografting, it was observed that the mice with miR-146b-3p agomir treatment had a lung metastasis (data not shown). At the end of the sixth week, as shown in Figure 5C, not only was tumor metastasis detected by in vivo bioluminescence imaging, but also pulmonary and LNM was observed by ex vivo fluorescence imaging. At the terminal detection, the tumor size of the treatment group with miR-146b-3p agomir treatment was slightly larger than that of the control group, but there was no significant difference (Fig. 5D). At the same time, compared to total metastasis in the control mice, the total metastasis occurrence number was much higher in the miR-146b-3p agomir-treated mice (1/10 vs. 3/5 separately; Fig. 5E). Histopathology with H&E staining was carried out to confirm the metastasis (Fig. 5F). To clarify the cellular mechanisms underlying miR-146b-3p-mediated tumor metastasis, resected tissues from those treated xenograft tumors were analyzed to verify miR-146b-3p and merlin expression. Consistent with the above results, at the endpoint of the experiment, miR-146b-3p agomir treatment significantly increased the expression of miR-146b-3p (Fig. 5G) and decreased the expression of merlin (Fig. 5H) in vivo. All these data indicate that high expression of miR-146b-3p could promote PTC tumor metastasis in vivo.

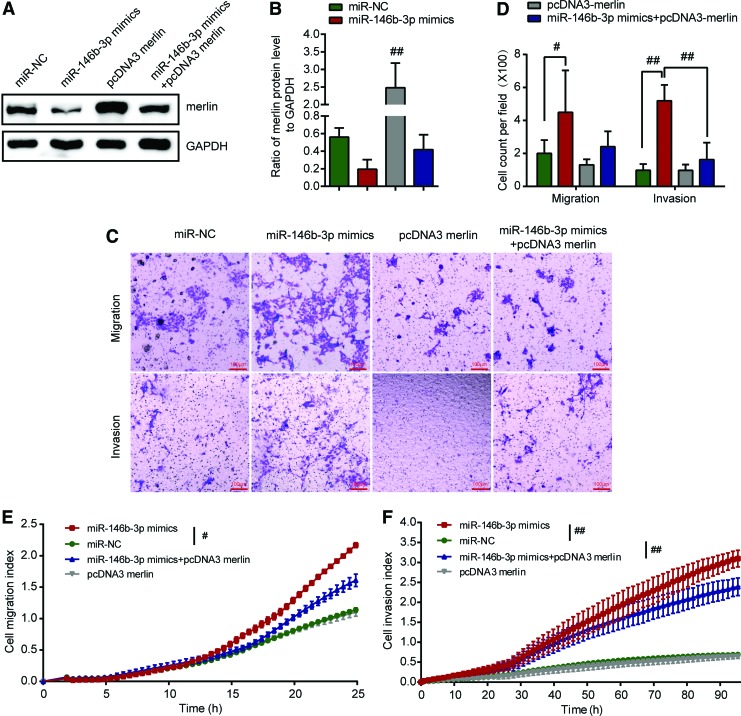

Reintroduction of NF2 abrogated the miR-146b-3p-induced metastasis enhancement

To confirm further that NF2 is the functional target gene of miR-146b-3p and that overexpression of merlin can attenuate the effect of miR-146b-3p on the metastatic abilities in BHP10-3 cells and K1 cells, miR-146b-3p mimics and pcDNA3 merlin were co-transfected into BHP10-3 cells and K1 cells using transfection with miR-146b-3p mimics, mimic controls, or pcDNA3 merlin as controls. As shown in Figure 6A and B and Supplementary Fig. S3A and B, the expression of merlin recovered after pcDNA3 merlin transfection. Interestingly, Transwell™ assays showed that the migration or invasive ability of BHP10-3 cells and K1 cells decreased after co-transfection with miR-146b-3p mimics and pcDNA3 merlin (Fig. 6C and D and Supplementary Fig. S3C and D). RTCA assay showed that compared to the migratory and invasive abilities of cells after miR-146b-3p mimic transfection, the migratory and invasive abilities of BHP10-3 cells decreased significantly in BHP10-3 cells co-transfected with miR-146b-3p mimics and pcDNA3 merlin (Fig. 6E and F). The results further revealed that reintroduction of merlin expression significantly abrogated the metastatic potential induced by miR-146b-3p in BHP10-3 cells, suggesting that NF2 is the functional target gene for miR-146b-3p in BHP10-3 cells.

FIG. 6.

Reintroduction of NF2 abrogates miR-146b-3p induced metastasis enhancement of BHP10-3 cells. BHP10-3 cells were co-transfected with miR-146b-3p mimics and pcDNA3 merlin or pcDNA3 (empty vector control), miR-NC (mimics control), or pcDNA3 merlin was respectively transfected into cells as control. (A) The protein level of endogenous merlin was detected by Western blot analysis after transfection. (B) The densitometric histogram of protein bands and results were expressed as ratio of corresponding protein to GAPDH. (C) Transwell™ assay was performed to determine the migration or invasive ability of BHP10-3 cells after being transfected for 24 or 48 h. Representative images show migrated or invasive BHP10-3 cells in the lower chamber stained with hematoxylin. (D) Cell count of Transwell™ assay for different treatment was statistically analyzed. (E and F) The migratory and invasive capacities of BHP10-3 cells were performed by RTCA assay after being transfected. #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 vs. miR-NC. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

Discussion

As the most common type of thyroid cancer, the incidence of PTC has increased rapidly in recent years (1). A substantial proportion of PTC patients, especially those with lymph node and distant metastasis, are prone to relapse and can have a poor prognosis. Identification of the molecular pathogenesis of PTC metastasis is important to identify effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for these patients. This study found that miR-146b-3p, as an ignored mature expression product of miR-146b, is significantly overexpressed in PTC metastasis lymph nodes and is positively correlated with migration and invasion abilities. In addition, the results demonstrate that the tumor suppressor gene NF2 is the target of miR-146b-3p. These findings might contribute to the early diagnosis and prevention of PTC metastasis.

MicroRNA expression is markedly tissue specific. Aberrant expression of tissue-specific miRNA is associated with various types of cancers arising in the lung, pancreas, breast, and colon (15). MiR-146b has been identified as an oncogene in PTC based on its increased expression in PTC tissue (14,39), but few studies have analyzed the expression of miR-146b in PTC with LNM. In particular, the relationship between miR-146b-5p and -3p and aggressive clinical pathological features of PTC remains unclear. Metastasis, which is the spread of cancer from its site of origin and subsequent colonization of distant organs, includes a multistage process involving cancer cell motility and transit in the blood or lymph. Only a subset of tumor cells with more aggressive characteristics can overcome these diverse challenges and produce colonization (40). Spreading of cancer cells by PTC occurs principally via the lymphatic system, resulting in regional LNM (41). Some publications have reported that miRNA-146b expression is increased in PTC or PTC with LNM in contrast to the expression in benign tissues or PTC without LNM by analyzing primary tumor samples of PTC patients with different degrees of aggressiveness (42). However, further analysis of the different expression levels of miR-146b between primary and metastatic lymph nodes from the same PTC patients, which can better reflect the characteristics of cell clusters tending to invade, has not been performed. On the other hand, miR-146b-5p, as the popular mature product of miR-146b, has been reported to be the major effective mature type, while the expression and function of miR-146b-3p has remained elusive.

This work focused on miR-146b expression in PTC with LNM and detected levels of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p in patients with PTC of different degrees of aggressiveness. Similar to the reports in the literature, upregulation of miR-146b-5p was confirmed in PTC with LNM compared to that in PTC without LNM. As expected, a similar phenomenon was detected for miR-146b-3p expression. Furthermore, the two mature types of miR-146b were analyzed among tissues pathologically confirmed as primary PTC and LNM, matched to adjacent non-neoplastic thyroid tissues and normal lymph node tissues from the same patient as controls. The results indicate that miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p expression is higher in PTC tissue compared to that in adjacent non-neoplastic thyroid tissue. Intriguingly, expression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p was further increased in thyroid metastatic lymph nodes compared to that in primary PTC, which indicates that the cell clusters that reached the lymph nodes expressed higher miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p levels, with stronger metastatic abilities. Further, the relationship between the expression of miR-146b-3p or -5p and clinicopathologic features of patients with PTC was analyzed. The expression levels of miR-146b-3p and miR-146b-5p were significantly positively associated with LNM. Because of the incomplete information for the other 17 PTC patients, follow-up was available only for a small portion (7/24) of the PTC patients, and none of these patients had a recurrence. There were no significant differences in the expression levels of miR-146b-3p or miR-146b-5p with other clinicopathologic parameters, including age at the time of diagnosis, multicentricity, and tumor staging. The results are partially consistent with a study by Han et al. (43) that demonstrated that miR-146b-3p, miR-146b-5p, and miR-222 are predictive of PTC associated with central LNM. These results suggest that upregulation of miR-146b-3p, consistent with miR-146b-5p, is positively correlated with PTC LNM. MiR-146b-3p, similar to miR-146b-5p, can be a predictor of thyroid tumorigenesis and metastatic ability in PTC.

To verify further the biological bases of the association between miR-146b-5p and -3p expression with PTC metastasis, PHT and PTC cell lines (BHP10-3 cells derived from RET/PTC1 rearrangement and K1 cells derived from BRAFV600E mutation) (44) were used to analyze the expression of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p. BHP10-3SCmice cells, as a colony of BHP10-3 with the same RET/PTC1 rearrangement background, proved extremely tumorigenic and invasive (28). It was interesting to observe that the expression of both miR-146b-5p and -3p increased in PTC cells, especially in BHP10-3SCmice cells, which was similar to the results in different samples of PTC patients. In addition, although the amount of miR-146b-3p was much lower than that of miR-146b-5p in PHT and different PTC cell lines, it was discovered that miR-146b-3p was more positively correlated with the invasion ability of PTC cells than miR-146b-5p.

MiR-146b-5p is a well characterized miRNA and is involved in many cancers, including lung and breast cancer and gliomablastomas (16–18). MiR-146b-5p enhances cell proliferation by repressing SMAD4 and disrupting TGF-β signal transduction in thyroid cancer (20). Recently, studies suggested that miR-146b-5p enhanced the migratory and invasive abilities in normal rat thyroid cell lines (PCCI3) and different tumor follicular cells (TPC-1 and BCPAP) (45). In these cell line studies, miR-146b-5p overexpression was achieved using expression of the PC-CMV-146b plasmid, which is also the precursor for miR-146b-3p. The effect on promoting cell migratory and invasive abilities may be the common effect of miR-146b-5p and -3p, rather than the individual action of miR-146b-5p. Deng et al. (21) presented that miR-146b-5p directly enhanced Wnt/β-catenin signaling through the downregulation of its target ZNRF3, thus promoting metastasis in PTC. However, the effect of miR-146b-3p was ignored.

In recent years, researchers have realized that although arising from the same precursor, unlike miR-146b-5p, miR-146b-3p might play a different and important role in cancer. Research on A549 lung cancer cells has shown that miR-146b-5p and miR-146b -3p have negative effects on the malignant phenotype of lung cancer cells (24). Garcilaso et al. (46) found that miR-146b-3p targets two genes, PAX8 and SLC5A5, key markers for differentiated thyroid phenotype, might modulate thyroid cell differentiation and iodide uptake for improved treatment of advanced thyroid cancer. In this research, miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p mimics or inhibitors were used to overexpress or inhibit different mature products of miR-146b separately. The effect of miR-146b-5p and miR-146b-3p overexpression on the metastatic nature of the BHP10-3 cells was determined using the RTCA migration and invasion assays. Unlike the Transwell™ migration and invasion assay as an endpoint assay, xCELLigence RTCA technology provided real-time data to be a highly accurate platform to monitor living cell behavior (47) and evaluate the migratory and invasive behaviors of BHP10-3 cells altered with miR-146b overexpression. Notably, miR-146b-3p enhances the migratory and invasive abilities more obviously than miR-146b-5p in the RTCA assay. Conventional Transwell™ migration and invasion assay correlate very well with this finding. These results indicate that instead of miR-146b-5p, miR-146b-3p plays a crucial role in promoting PTC cell metastasis and is specifically involved in PTC cell migration and invasion.

To illustrate how miRNA-146b-3p promotes the invasion and migration of PTC, the study screened for potential target genes of miR-146b-3p by bioinformatics software and identified NF2 and MTSS1. Subsequent studies using luciferase reporter assays revealed that miR-146b-3p binds directly to the 3′ UTR of NF2 but not MTSS1. Germline and somatic mutations in the NF2 gene have been detected in hereditary and sporadic tumors. In the familial syndrome, a germline mutations is found, together with an acquired somatic mutation (Knudson two-hit mechanism) (48). NF2 was originally reported in the neurofibromatosis type 2 cancer syndrome, which is characterized by a highly specific subset of central and peripheral nervous system tumors (29). Studies have revealed that as a tumor suppressor gene, NF2 plays a broad role in restraining cell proliferation by regulating several important signaling pathways, such as the mTOR, PI3K/AKT, and hippo signaling pathways (29,49–51), and it translocates to the nucleus to inhibit CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase (52). NF2 was one of the most frequent allelic losses (75%) in medullary thyroid carcinomas (53). Recently, Fagin et al. demonstrated that NF2/merlin inactivation improves mutant RAS signaling by promoting YAP/TEAD-driven oncogenic transcription, resulting in development of poorly differentiated thyroid cancers (54). Furthermore, the ever-increasing breadth of mechanistic insights revealed that NF2 plays a crucial role in tumor metastasis. McClatchey et al. (55) observed that NF2 heterozygous mice develop multiple malignant tumor types with a high frequency of metastasis to distant sites. However, whether NF2 contributes to PTC metastasis remains unclear.

This study first elucidated that the enhanced effects of miR-146b-3p on PTC cell migration and invasion abilities were attenuated by reintroduction of merlin expression, which suggests that NF2/merlin is involved in the regulation of PTC cell metastasis. Notably, although some studies (56–58) reported that merlin could interact with adherens junctions, which are firmly linked to tumor invasion, and suppress tumor metastasis by attenuating the FOXM1-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling, the expression of β-catenin was unchanged when miR-146b-3p or merlin was overexpressed (data not shown), suggesting that NF2/merlin inhibited PTC metastasis in a Wnt/β-catenin-independent manner. Additional studies regarding the potential mechanisms will be done in the future.

The study also verified the role of miR-146b-3p on PTC metastatic ability in vivo. Due to the limitation of relatively low tumorigenicity and aggressiveness of PTC, there is no highly aggressive PTC animal model that can be used to evaluate the potential treatment effect of miR-146b-3p inhibition. An in vivo nude mouse xenograft model with high PTC tumorigenicity cells was used, and the miR-146b-3p agomir was subsequently injected into the tumor in situ. Although the tumor volumes in nude mice were not markedly changed, the ratio of lymph node and distant metastasis was significantly increased in high miR-146b-3p expression cancers compared to the control PTC. Additionally, the level of merlin notably decreased with the increased miR-146b-3p expression. These results further indicate that high expression of miR-146b-3p inhibit expression of merlin and promote PTC tumor metastasis in vivo.

In summary, the present results demonstrate that miR-146b-3p, as one mature product of miR-146b, is notably upregulated in PTC with LNM and metastatic lymph nodes and plays a more important role than miR-146b-5p in human PTC cell migration and invasion by directly targeting NF2. These findings are important for the early diagnosis of PTC patients with the tendency to develop metastases and aggressive phenotypes. Moreover, these findings may provide new gene therapy targets for PTC metastasis in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to dedicate this paper to Tong Jin, who unfortunately passed away before the paper was submitted for publication. Jin played an essential role in the research and he is greatly missed. We appreciated Dr. Gary Clayman (The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) for providing the PTC cell lines BHP10-3 and BHP10-3SCmice, and Dr. Xingsong Tian (Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery, Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China) for providing the PTC cell lines K1. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (81101590, 81770860) of China.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1. Sprague BL, Andersen SW, Trenthamdietz A. 2008. Thyroid cancer incidence and socioeconomic indicators of health care access. Cancer Causes Control 19:585–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bartel DP. 2009. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136:215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Di Leva G, Croce CM. 2010. Roles of small RNAs in tumor formation. Trends Mol Med 16:257–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iorio MV, Croce CM. 2012. MicroRNA dysregulation in cancer: diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics. A comprehensive review. EMBO Mol Med 4:143–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He H, Jazdzewski K, Li W, Liyanarachchi S, Nagy R, Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu C, Franssila K, Suster S. 2005. The role of microRNA genes in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:19075–19080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nikiforova MN, Tseng GC, Steward D, Diorio D, Nikiforov YE. 2008. MicroRNA expression profiling of thyroid tumors: biological significance and diagnostic utility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1600–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen YT, Kitabayashi N, Zhou XK, Fahey TJ, Scognamiglio T. 2008. MicroRNA analysis as a potential diagnostic tool for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mod Pathol 21:1139–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheu SY, Grabellus F, Schwertheim S, Worm K, Broeckerpreuss M, Schmid KW. 2010. Differential miRNA expression profiles in variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma and encapsulated follicular thyroid tumours. Br J Cancer 102:376–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nikiforova MN, Chiosea SI, Nikiforov YE. 2009. MicroRNA expression profiles in thyroid tumors. Endocr Pathol 20:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li X, Abdelmageed AB, Mondal D, Kandil E. 2013. MicroRNA expression profiles in differentiated thyroid cancer, a review. Int J Clin Exp Med 6:74–80 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gao Y, Wang C, Shan Z, Guan H, Mao J, Fan C, Wang H, Zhang H, Teng W. 2010. miRNA expression in a human papillary thyroid carcinoma cell line varies with invasiveness. Endocr J 57:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yip L, Kelly L, Shuai Y, Armstrong MJ, Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Nikiforova MN. 2011. MicroRNA signature distinguishes the degree of aggressiveness of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 18:2035–2041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chou CK, Chen RF, Chou FF, Chang HW, Chen YJ, Lee YF, Yang KD, Cheng JT, Huang CC, Liu RT. 2010. miR-146b is highly expressed in adult papillary thyroid carcinomas with high risk features including extrathyroidal invasion and the BRAF(V600E) mutation. Thyroid 20:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calin GA, Croce CM. 2006. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 6:857–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katakowski M, Zheng X, Jiang F, Rogers T, Szalad A, Chopp M. 2010. MiR-146b-5p suppresses EGFR expression and reduces in vitro migration and invasion of glioma. Cancer Invest 28:1024–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hurst DR, Edmonds MD, Scott GK, Benz CC, Vaidya KS, Welch DR. 2011. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 up-regulates miR-146, which suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res 69:1279–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xia H, Qi Y, Ng SS, Chen X, Li D, Chen S, Ge R, Jiang S, Li G, Chen Y. 2009. microRNA-146b inhibits glioma cell migration and invasion by targeting MMPs. Brain Res 1269:158–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fabbri M, Ivan M, Cimmino A, Negrini M, Calin GA. 2007. Regulatory mechanisms of microRNAs involvement in cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther 7:1009–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geraldo MV, Yamashita AS, Kimura ET. 2012. MicroRNA miR-146b-5p regulates signal transduction of TGF-Î2 by repressing SMAD4 in thyroid cancer. Oncogene 31:1910–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deng X, Wu B, Xiao K, Kang J, Xie J, Zhang X, Fan Y. 2015. MiR-146b-5p promotes metastasis and induces epithelial–mesenchymal transition in thyroid cancer by targeting ZNRF3. Cell Physiol Biochem 35:71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jing Z, Yang L, Zheng L, Wang XM, Yin DT, Zheng LL, Zhang DY, Lu XB. 2013. Differential expression profiling and functional analysis of microRNAs through stage I–III papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Med Sci 10:585–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang Z, Yuan Z, Fan Y, Deng X, Zheng Q. 2013. Integrated analyses of microRNA and mRNA expression profiles in aggressive papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mol Med Rep 8:1353–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patnaik SK, Kannisto E, Mallick R, Yendamuri S. 2011. Overexpression of the lung cancer-prognostic miR-146b microRNAs has a minimal and negative effect on the malignant phenotype of A549 lung cancer cells. Plos One 6:e22379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang L, Xu J, Sun N, Cai H, Ren M, Zhang J, Yu C, Wang Z, Gao L, Zhao J. 2013. The presence of adenosine A2a receptor in thyrocytes and its involvement in Graves' IgG-induced VEGF expression. Endocrinology 154:4927–4938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ambesiimpiombato FS, Parks LA, Coon HG. 1980. Culture of hormone-dependent functional epithelial cells from rat thyroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:3455–3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Solly K, Wang X, Xu X, Strulovici B, Zheng W. 2004. Application of real-time cell electronic sensing (RT-CES) technology to cell-based assays. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2:363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ahn SH, Henderson Y, Kang Y, Chattopadhyay C, Holton P, Wang M, Briggs K, Clayman GL. 2008. An orthotopic model of papillary thyroid carcinoma in athymic nude mice. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134:190–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bianchi AB, Hara T, Ramesh V, Gao J, Kleinszanto AJP, Morin F, Menon AG, Trofatter JA, Gusella JF, Seizinger BR. 1994. Mutations in transcript isoforms of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene in multiple human tumour types. Nat Genet 6:185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheng JQ, Lee W, Klein MA, Cheng GZ, Jhanwar SC, Testa JR. 1999. Frequent mutations of NF2 and allelic loss from chromosome band 22q12 in malignant mesothelioma: evidence for a two-hit mechanism of NF2 inactivation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 24:238–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C. 2010. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature 463:360–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rustgi AK, Xu L, Pinney D, Sterner C, Beauchamp R, Schmidt S, Gusella JF, Ramesh V. 1995. Neurofibromatosis 2 gene in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 84:24–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee YG, Macoska JA, Korenchuk S, Pienta KJ. 2002. MIM, a potential metastasis suppressor gene in bladder cancer. Neoplasia 4:291–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loberg RD, Neeley CK, Adamday LL, Fridman Y, St John LN, Nixdorf S, Jackson P, Kalikin LM, Pienta KJ. 2005. Differential expression analysis of MIM (MTSS1) splice variants and a functional role of MIM in prostate cancer cell biology. Int J Oncol 26:1699–1705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parr C, Jiang WG. 2009. Metastasis suppressor 1 (MTSS1) demonstrates prognostic value and anti-metastatic properties in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 45:1673–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ke L, Wang G, Ding H, Ying C, Yu G, Wang J. 2010. Downregulation of metastasis suppressor 1(MTSS1) is associated with nodal metastasis and poor outcome in Chinese patients with gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 10:428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mertz KD, Pathria G, Wagner C, Saarikangas J, Sboner A, Romanov J, Gschaider M, Lenz F, Neumann F, Schreiner W. 2014. MTSS1 is a metastasis driver in a subset of human melanomas. Nat Commun 5:3465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ma S, Guan XY, Lee TK, Chan KW. 2007. Clinicopathological significance of missing in metastasis B expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol 38:1201–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chou CK, Yang KD, Chou FF, Huang CC, Lan YW, Lee YF, Kang HY, Liu RT. 2013. Prognostic implications of miR-146b expression and its functional role in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:196–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin JD. 2007. Papillary thyroid carcinoma with lymph node metastases. Growth Factors 25:41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sahai E. 2007. Illuminating the metastatic process. Nat Rev Cancer 7:737–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saiselet M, Gacquer D, Spinette A, Craciun L, Decaussin-Petrucci M, Andry G, Detours V, Maenhaut C. 2015. New global analysis of the microRNA transcriptome of primary tumors and lymph node metastases of papillary thyroid cancer. BMC Genomics 16:828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Han PA, Kim HS, Cho S, Fazeli R, Najafian A, Khawaja H, McAlexander M, Dy B, Sorensen M, Aronova A, Sebo TJ, Giordano TJ, Fahey TJ, 3rd, Thompson GB, Gauger PG, Somervell H, Bishop JA, Eshleman JR, Schneider EB, Witwer KW, Umbricht CB, Zeiger MA. 2016. Association of BRAF V600E mutation and microRNA expression with central lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid cancer: a prospective study from four endocrine surgery centers. Thyroid 26:532–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schweppe RE, Klopper JP, Korch C, Pugazhenthi U, Benezra M, Knauf JA, Fagin JA, Marlow LA, Copland JA, Smallridge RC, Haugen BR. 2008. Deoxyribonucleic acid profiling analysis of 40 human thyroid cancer cell lines reveals cross-contamination resulting in cell line redundancy and misidentification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4331–4341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lima CR, Geraldo MV, Fuziwara CS, Kimura ET, Santos MF. 2016. MiRNA-146b-5p upregulates migration and invasion of different papillary thyroid carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 16:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Riescoeizaguirre G, Wertlamas L, Peralespatón J, Sastreperona A, Fernández LP, Santisteban P. 2015. The miR-146b-3p/PAX8/NIS regulatory circuit modulates the differentiation phenotype and function of thyroid cells during carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 75:4119–4130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kramer AH, Joos-Vandewalle J, Edkins AL, Frost CL, Prinsloo E. 2014. Real-time monitoring of 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation using a commercially available electric cell-substrate impedance sensor system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 443:1245–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xiao GH, Chernoff J, Testa JR. 2003. NF2: the wizardry of merlin. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 38:389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morrison H, Sherman LS, Legg J, Banine F, Isacke CM, Haipek CA, Gutmann DH, Ponta H, Herrlich P. 2001. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, mediates contact inhibition of growth through interactions with CD44. Genes Dev 15:968–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stamenkovic I, Yu Q. 2010. Merlin, a “magic” linker between extracellular cues and intracellular signaling pathways that regulate cell motility, proliferation, and survival. Curr Protein Peptide Sci 11:471–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Petrilli AM, Cristina FV. 2016. Role of Merlin/NF2 inactivation in tumor biology. Oncogene 35:537–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li W, You L, Cooper J, Schiavon G, Pepe-Caprio A, Zhou L, Ishii R, Giovannini M, Hanemann CO, Long SB. 2010. Merlin/NF2 suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4DCAF1 in the nucleus. Cell 140:477–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sheikh HA, Tometsko M, Niehouse L, Aldeeb D, Swalsky P, Finkelstein S, Barnes EL, Hunt JL. 2004. Molecular genotyping of medullary thyroid carcinoma can predict tumor recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol 28:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Garciarendueles MER, Ricartefilho JC, Untch BR, Landa I, Knauf JA, Voza F, Smith VE, Ganly I, Taylor BS, Persaud Y. 2015. NF2 loss promotes oncogenic RAS-induced thyroid cancers via YAP-dependent transactivation of RAS proteins and sensitizes them to MEK inhibition. Cancer Discov 5:1178–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mcclatchey AI, Saotome I, Mercer K, Crowley D, Gusella JF, Bronson RT, Jacks T. 1998. Mice heterozygous for a mutation at the Nf2 tumor suppressor locus develop a range of highly metastatic tumors. Genes Dev 12:1121–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gladden AB, Hebert AM, Schneeberger EE, Mcclatchey AI. 2010. The NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin, regulates epidermal development through the establishment of a junctional polarity complex. Dev Cell 19:727–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lallemand D, Curto M, Saotome I, Giovannini M, Mcclatchey AI. 2003. NF2 deficiency promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis by destabilizing adherens junctions. Genes Dev 17:1090–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Quan M, Cui J, Xia T, Jia Z, Xie D, Wei D, Huang S, Huang Q, Zheng S, Xie K. 2015. Merlin/NF2 suppresses pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis by attenuating the FOXM1-mediated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Res 75:4778–4789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.