Abstract

Background

Stigma affects the quality of life of the mentally ill, and health professionals are considered to be involved in possessing negative attitudes towards them. We evaluated the prevalence of stigmatization among different health professionals in Nigerian hospitals.

Methods

This study was a descriptive, cross-sectional and comparative survey assessing attitudinal views of health professionals (doctors, pharmacists, and nurses) regarding mental illness in two hospitals in Eastern Nigeria. The survey utilized the 40-item Community Attitude to Mental Illness, CAMI-2 questionnaire. The prevalence and the factors that contribute to negative attitudes among this cohort were assessed. Statistical analysis using T-tests, ANOVA and Pearson Correlation were conducted.

Results

Attitudes to all the four constructs of the CAMI-2 were non-stigmatizing. Stigmatizing attitudes were significantly higher among pharmacists, doctors and then nurses (p<0.006). Health professionals who did not have contact with the mentally ill (p<0.0001), who were males (p=0.008) and had lower years of working experience (p=0.031) expressed significantly higher stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill. Conclusions: Nigerian health professionals were largely non-stigmatizing towards the mentally ill. However, being a pharmacist, of male gender, and working in a non-psychiatric hospital were associated with stigmatizing attitudes when they exist.

Keywords: Mental illness, Stigma, Health Professionals, Survey

Introduction

Worldwide, the stigma of mental illness is a huge problem that leads to profound distress and disability that negatively affects the quality of life (1). Mental illness has also been identified as the leading cause of disability in the United States of America (2). Stigma towards people with mental illness is both a longstanding and widespread phenomenon (3). The more a mentally ill persons feel stigmatized, the lower is their self-esteem, social adjustment and quality of life (5–6). Stigma also influences access to care, because people may be reluctant to seek help despite experiencing mental or emotional problems as this might be seen as an acknowledgment of weakness or failure (7). Negative and stigmatizing attitudes towards mentally ill persons, therefore, have direct implications for the prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and quality of life of those affected.

According to the Mental health Commission of Canada, people with mental illness experience some of the most deeply felt stigma from health professionals (8). A study of the attitudes of doctors towards people with mental illness in Western Nigeria showed that they considered people with mental illness to be unpredictable, dangerous, without self-control and aggressive, similar to the perceived public views in very many countries (9). Stigma affects the health professional's readiness to provide wholesome interventions for individuals with psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, stigma promotes discrimination, increases the burden experienced by patients and their caregivers, and places restrictions on social integration (10).

In order to effectively provide care, the attitudes of health professionals towards psychiatric patients are important and need to be evaluated consistently. Stigmatization of people with mental illness is very prevalent in developing African settings like Nigeria (11). Stigma also remains a strong barrier to accessing mental health services in Nigeria (12). However, only a little information is available on the prevalence of stigmatizing attitudes among health professionals towards mentally ill patients.

The objectives of this study were to (1) evaluate the attitudes towards psychiatric patients among health professionals (Physicians, Pharmacists and Nurses) in two tertiary hospitals in Enugu State, Nigeria, and (2) assess any differences in the levels of stigmatization towards these psychiatric patients using demographic characteristics of the health care providers.

Methods

Attitude to Mental Illness CAMI-2, was used to conduct the survey (13). The scale includes 40 items to be rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) and is organized into four apriori dimensions of ten items

Design: This study was a descriptive, cross-sectional and comparative survey. It assessed attitudinal views of health professionals (specifically doctors, nurses, and pharmacists) in two tertiary hospitals in Eastern Nigeria regarding patients with mental illnesses. The survey was conducted between June and August, 2016.

Study settings: The two tertiary hospitals used in this survey were the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital and the Enugu State University Teaching Hospital. Both hospitals are located in Enugu State, the largest capital city in the Eastern region of Nigeria.

The Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Enugu, is a 180-beds tertiary healthcare delivery center which provides care for patients with mental illnesses. It is the only psychiatric specialty hospital located in South-Eastern Nigeria and acts as a referral for patients from the five states of this region.

The Enugu State University of Science and Technology Teaching Hospital (ESUT-TH) is a 400-beds state government funded tertiary hospital offering basic and specialized health care services to the entire people of Enugu. It does not offer specialist psychiatric services to patients visiting the hospital.

Study participants: The study population comprised all the physicians, pharmacists and nurses working in both hospitals. A sampling of eligible participants was done by convenience from an estimated workforce pool of 680 health professionals comprising of only doctors, nurses and pharmacists (438 from ESUTH and 242 from FNH).

Ethical approval: An application to carry out this study was made to the Ethics and Research Review Boards of both hospitals, and approvals were obtained before the commencement of the study.

Study instrument: A previously validated and widely utilized questionnaire, Community each: Authoritarianism (AU), Benevolence (BE), Social Restrictiveness (SR) and Community Mental Health Ideology (CMHI). These dimensions create a scale that discriminates between respondents with “stigmatizating” and “non-stigmatizating” attitudes towards people with mental illness.

The CAMI-2 is scored by assigning values to each of the items. Five of the ten items for each factor are reverse-coded. Likert-type responses (5= strongly agree to 1= strongly disagree) are given to each question. Internal consistency of the CAMI constructs has been rated as moderate to good AU (α= 0.68), CMHI (α= 0.88), SR (α= 0.80), and BE (α=0.76) (13).

Procedure: Eligible participants were approached either in their offices or during unit/clinical meetings. All participants in this study gave consent before being handed in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was self-administered, and it took most of the participants an average of 20 minutes to complete.

Statistical analysis: Data from retrieved questionnaires were coded appropriately into the Microsoft 2010 Excel Spreadsheet and later transferred into the SPSS version 20, IL, USA for statistical analysis. To obtain the distribution of opinions and prevalence of stigmatization towards people with mental illnesses, responses to the CAMI instrument were subjected to simple frequency and mean (SD). Also, responses from each questionnaire were grouped proportionally as “stigmatization” (represented by mean scores below 3.0) and “non-stigmatization” (represented by mean scores below 3.0) and distributed by hospital setting type (psychiatric and non-psychiatric), health professional category, age, gender and years of experience by using cross tabulation and their differences reported with chi-square.

Responses on the CAMI dimensions presented as mean scores and mean differences by the independent variables (age, gender, profession and hospital setting) were analyzed using independent sample t-tests (for two groups) and Analysis of Variance (for more than two groups). Lastly, a Pearson's correlation analysis was used to identify demographic associating factors of stigmatization among these health professionals. All significant levels of P-values were set at <0.05.

Results

This survey recorded a participation rate of 44.8% (305/680) with nearly equal response rates from both hospitals (44.2% vs. 45.2%, p=0.88). The distribution of health professionals were as follows: doctors (n=116), nurses (n=110) and pharmacists (n=77). More health professionals practicing in the non-psychiatric hospital, representing nearly two-third (n=198, 64.9%) of the sample participated in the survey. There were also mostly young and middle aged health professionals in this study (25 – 45 years old) accounting for 93.1% of participants. There were fewer female health professionals in this survey (n=119, 39.0%), and the mean duration of experience among these health professionals was 6 years, 11 months and 8 days.

For statements on the authoritarianism scale of the CAMI instrument, the overall response to the authoritarianism construct was marginally non-stigmatizing producing a mean (SD) response of 2.87 (0.52). As shown in Table 1, the mean scores of five of the ten responses from health professionals from both hospitals were “stigmatizing”, i.e. having scores above the mid-point of 3.0. Specifically, stigmatization was highest with the statements “Mental hospitals are an out-dated means of treating the mentally ill” and “There is something about the mentally ill that makes it easy to tell them from normal people”, both scoring mean responses of 4.16 and 3.69 respectively

Table 1.

Health professionals' opinions on the authoritarianism scale of the CAMI instrument (N=304)

| Items on Authoritarianism (AU) | Strongly agree/agree (%) |

Neutral (%) |

Strongly disagree/ disagree (%) |

Mean | SD |

| One of the main causes of mental illness is a lack of self-discipline and will power (strongly agree/agree) |

101 (33.2) | 54 (17.7) | 149 (49.1) | 2.72 | 1.33 |

| The best way to handle the mentally ill is to keep them behind locked doors (strongly agree/agree) |

20 (6.6) | 16 (5.2) | 269 (88.2) | 1.73 | 0.90 |

| There is something about the mentally ill that makes it easy to tell them from normal people (strongly agree/agree) |

211 (70.6) | 37 (12.3) | 51 (17.1) | 3.69 | 1.13 |

| As soon as a person shows signs of mental disturbance, he should be hospitalized (strongly agree/agree) |

168 (55.1) | 26 (8.5) | 111 (36.4) | 3.30 | 1.32 |

| Mental patients need the same kind of control and discipline as a young child (strongly agree/agree) |

157 (52.0) | 38 (12.6) | 107 (35.4) | 3.19 | 1.21 |

| Mental illness is an illness like any other (strongly disagree/disagree) |

167 (55.1) | 22 (7.3) | 114 (37.6) | 2.79 | 1.86 |

| The mentally ill should not be treated as outcasts of the society (strongly disagree/disagree) |

255 (85.0) | 4 (1.3) | 41 (13.7) | 1.80 | 1.24 |

| Less emphasis should be placed on protecting the public from the mentally ill (strongly disagree/disagree) |

97 (32.4) | 38 (12.7) | 164 (54.8) | 3.34 | 1.28 |

| Large mental hospitals are an outdated means of treating the mentally ill (strongly disagree/disagree) |

27 (9.0) | 21 (7.0) | 253 (84.0) | 4.16 | 1.05 |

| Virtually anyone can become mentally ill (strongly disagree/disagree) |

239 (79.7) | 33 (11.0) | 28 (9.3) | 1.98 | 0.99 |

Responses in parenthesis signify stigmatizing attitudes towards mentally ill patients.

Items on the authoritarianism scale were adopted from Taylor and Dear (13).

Overall construct mean (SD) score = 2.87 ± 0.52; Higher mean scores signify higher stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill.

One can see from Table 2 that the overall response to the benevolence construct was also non-stigmatizing, i.e. the mean (SD) construct response of 2.20 (0.41). In addition, as it is indicated in the table, the responses to all the items were at or below the midpoint value for stigmatization.

Table 2.

Health professionals' opinions on the benevolence construct of the CAMI instrument

| Items on Benevolence (BE) | Strongly agree/agree (%) |

Neutral (%) | Strongly disagree/ disagree (%) |

Mean | SD |

| 1. The mentally ill have for too long been the subject of ridicule (strongly | 229 (76.6) | 34 (11.4) | 46 (12.0) | 2.15 | 1.01 |

| disagree/disagree) | |||||

| 2. More tax money should be spent on the care and treatment of the mentally ill | 227 (75.2) | 52 (17.2) | 23 (7.6) | 2.04 | 0.94 |

| (strongly disagree/disagree) | |||||

| 3. We need to adopt a far more tolerant attitude towards the mentally ill in our | 292 (96.4) | 7 (2.3) | 4 (1.3) | 1.63 | 0.93 |

| society (strongly disagree/disagree) | |||||

| 4. Our mental hospitals seem more like prisons than like places where the | 126 (41.7) | 49 (16.2) | 127 (42.0) | 3.00 | 1.27 |

| mentally ill can be cared for (strongly disagree/disagree) | |||||

| 5. We have a responsibility to provide the best possible care for the mentally ill | 286 (95.0) | 9 (3.0) | 6 (2.0) | 1.53 | 0.68 |

| (strongly disagree/disagree) | |||||

| 6. The mentally ill don't deserve our sympathy (strongly agree/agree) | 27 (9.0) | 22 (7.3) | 252 (83.7) | 1.69 | 1.02 |

| 7. The mentally ill are a burden on society (strongly agree/agree) | 81 (26.9) | 37 (12.3) | 183 (60.8) | 2.41 | 1.34 |

| 8. Increased spending on mental health services is a waste of tax (strongly | 13 (3.7) | 10 (3.4) | 277 (92.9) | 1.56 | 0.81 |

| agree/agree) | |||||

| 9. There are sufficient existing services for the mentally ill (strongly | 45 (15.0) | 48 (26.0) | 207 (69.0) | 2.25 | 1.05 |

| agree/agree) | |||||

| 10. It is best to avoid anyone who has mental problems (strongly agree/agree) | 27 (9.1) | 30 (10.1) | 139 (80.8) | 1.95 | 1.03 |

Responses in parenthesis signify stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill patient.

Items on the benevolence scale were adopted from Taylor and Dear (13).

Overall construct mean (SD) score = 2.02 ± 0.41; Higher mean scores signify higher stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill.

With a striking similarity with the benevolence construct, health professionals' responses to the social restrictiveness construct were also non-stigmatizing, mean (SD), 2.30 (0.42) with nearly all its items receiving responses below the mid 3.0 score. However, one statement regarding previously mentally ill patients being allowed to be babysitters received stigmatizing responses from the majority (51.3%), representing a mean (SD) item score of 3.53 (0.96) of the respondents. Other results on this construct are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Health professionals' opinions on the social restrictiveness construct of the CAMI instrument

| Items on Social Restrictiveness (SR) | Strongly | Neutral | Strongly disagree/ | Mean | SD |

| agree/agree (%) | (%) | disagree (%) | |||

| 1. The mentally ill should not be given any responsibility (strongly agree/agree) | 57 (19.) | 44 (14.7) | 199 (66.3) | 2.38 | 1.12 |

| 2. The mentally ill should be isolated from the rest of the community (strongly agree/agree) |

35 (11.8) | 30 (10.1) | 132 (78.1) | 2.00 | 1.06 |

| 3. A woman would be foolish to marry a man who has suffered from mental illness, even though he seems fully recovered (strongly agree/agree) |

27 (9.0) | 82 (27.2) | 192 (63.8) | 2.26 | 0.96 |

| 4. I would not want to live next door to someone who has been mentally ill (strongly agree/agree) |

43 (14.2) | 75 (24.8) | 184 (60.9) | 2.40 | 1.00 |

| 5. Anyone with a history of mental problems should be excluded from taking public office (strongly agree/agree) |

58 (16.0) | 44 (14.7) | 208 (69.3) | 2.30 | 1.06 |

| 6. The mentally ill should not be denied their individual rights (strongly disagree/disagree) |

265 (89.5) | 3 (1.0) | 28 (9.5) | 1.76 | 1.02 |

| 7. Mental patients should be encouraged to assume the responsibilities of normal life (strongly disagree/disagree) |

263 (87.7) | 15 (5.0) | 22 (5.3) | 1.87 | 0.88 |

| 8. No one has the right to exclude the mentally ill from their neighborhood (strongly disagree/disagree) |

236 (78.7) | 35 (11.7) | 29 (9.6) | 2.02 | 0.94 |

| 9. The mentally ill are far less a danger than most people suppose (strongly disagree/disagree) |

168 (56.2) | 79 (26.4) | 52 (17.4) | 2.50 | 1.04 |

| 10. Most women who were once patients in a mental hospital can be trusted as babysitters (strongly disagree/disagree) |

39 (13.4) | 103 (35.3) | 160 (51.3) | 3.53 | 0.96 |

Responses in parenthesis signify stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill patient.

Items on the social restrictiveness scale were adopted from Taylor and Dear (13).

Overall construct mean (SD) score = 2.30 ± 0.42; Higher mean scores signify higher stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill.

Lastly, for the instrument's constructs, responses to the community mental health ideology were marginally non-stigmatizing mean (SD) construct score of 2.61 (0.40) with three of the ten items receiving stigmatizing responses from health professionals. About half of these health professionals were discriminatory in items such as “Having mental patients live within residential neighborhoods might be good therapy, but the risks were too great” 51.8%; mean (SD) response of 3.34 (1.14) and “It is frightening to think of people with mental problems living in residential neighborhoods” (48.8%; mean (SD) - 3.21 (1.16). Also, nearly half (52.4%) of the health professional agreed or remained neutral when asked if local residents should resist the location of mental health services in their neighborhoods. Summary results can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Health professionals' opinions on the community mental health ideology construct of the CAMI instrument

| Items on Community Mental Health Ideology (CMHI) | Strongly agree/agree (%) |

Neutral (%) | Strongly disagree/ disagree (%) |

Mean | SD |

| 1. Residents should accept the location of mental health facilities in their neighborhood (strongly disagree/disagree) |

201 (67.0) | 55 (18.3) | 44 (14.7) | 2.27 | 1.06 |

| 2. The best therapy for many mental patients is to be part of a normal community (strongly disagree/disagree) |

127 (76.2) | 40 (13.4) | 31 (10.4) | 2.11 | 0.96 |

| 3. As far as possible, mental health services should be provided through community based facilities (strongly disagree/disagree) |

247 (82.6) | 19 (6.4) | 33 (11.0) | 2.03 | 0.97 |

| 4. Locating mental health services in residential neighborhoods does not endanger local residents (strongly disagree/disagree) |

160 (53.2) | 55 (18.3) | 86 (28.5) | 2.65 | 1.18 |

| 5. Residents have nothing to fear from people coming into their neighborhood to obtain mental health services (strongly disagree/disagree) |

188 (62.7) | 61 (20.3) | 51 (17.0) | 2.42 | 1.03 |

| 6. Mental health facilities should be kept out of residential neighborhoods (strongly agree/agree) |

95 (32.2) | 64 (21.7) | 136 (46.1) | 2.82 | 1.21 |

| 7. Local residents have good reasons to resist the location of mental health services in their neighborhood (strongly agree/agree) |

118 (39.6) | 68 (22.8) | 112 (47.6) | 3.01 | 1.24 |

| 8. Having mental patients live within residential neighborhoods might be good therapy but the risks for the residents are too great (strongly agree/agree) |

156 (51.8) | 67 (22.3) | 78 (25.9) | 3.34 | 1.14 |

| 9. It is frightening to think of people with mental problems living in residential neighborhoods (strongly agree/agree) |

146 (48.8) | 52 (17.4) | 101 (33.8) | 3.21 | 1.16 |

| 10. Locating mental health facilities in a residential area downgrades the neighborhood (strongly agree/agree) |

37 (12.3) | 46 (15.3) | 218 (72.4) | 2.21 | 1.09 |

Responses in parenthesis signify stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill patient.

Items on the community mental health ideology scale were adopted from Taylor and Dear (13).

Overall construct mean (SD) score = 2.61 ± 0.40; Higher mean scores signify higher stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill.

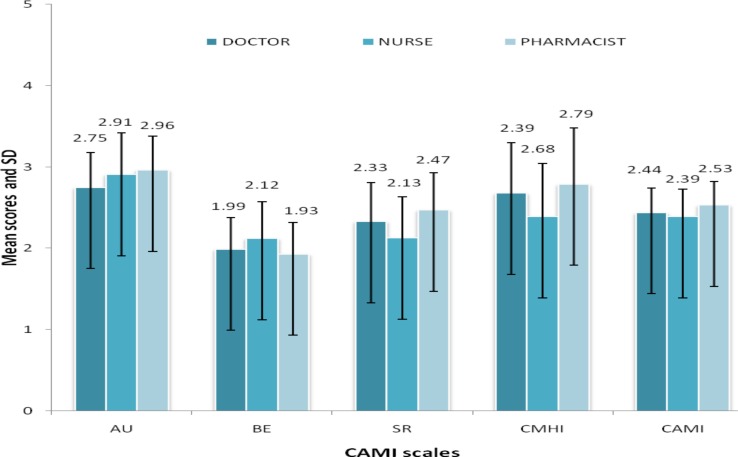

Pharmacists were significantly more stigmatizing in three of the four constructs (mean score (SD); AU 2.96 (0.42), p=0.004; SR 2.47 (0.46), p<0.0001; CMHI 2.79 (0.69), p<0.0001) than other health professionals. Nurses, on the other hand, produced a significantly higher stigmatizing attitude than doctors and pharmacists in the benevolence construct (mean score (SD); BE 2.12 (0.45), p=0.006). Overall, for the CAMI instrument, pharmacists were more stigmatizing than doctors who were more stigmatizing than the nurses, p=0.006. These results are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean scores of the CAMI subscales by profession (doctors n = 116, nurses n = 110, pharmacist n = 77). AU=Authoritarianism, BE= Benevolence, SR= Social restrictiveness, CMHI= Community Mental Health Ideology, CAMI= Community Attitude To Mental Illness. Higher scores indicate stigmatization. Error bars show standard deviations. *p < 0.05, †p <0.001 (ANOVA).

When grouping the study participants into different hospital settings and service provisions, considerable significant differences were observed between health professionals who were working with mentally ill patients and those who were not (Figure 1). Health professionals not working with mentally ill patients expressed more stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill in all but one of the CAMI constructs (mean score (SD); AU 2.92 (0.42), p=0.004; SR 2.40 (0.51), p<0.0001; CMHI 2.79 (0.65), p<0.0001) compared to those working with mentally ill patients. Overall, health professionals without contact with mentally ill were more stigmatizing than their other counterparts (2.54 vs. 2.28, p<0.0001).

Correlation analysis results revealed a moderate association (r = −0.383, p<0.0001) between hospital settings and level of expression of stigmatizing attitudes (Table 5). This suggests that working directly with mentally ill patients would likely be associated with lower stigmatization towards them.

Table 5.

Demographic correlates of health professionals' discriminatory attitudes towards the mentally ill

| Variables | Correlation factor (r) | ||||

| Stigmatization | Hospital | Age | Gender | Experience | |

| Stigmatization | −0.383† | −0.124* | −0.157* | −0.130* | |

| Hospital | −0.383− | 0.068 | −0.080 | 0.166* | |

| Age | −0.124* | 0.068 | −0.200* | 0.592† | |

| Gender | 0.157* | −0.080 | −0.200* | −0.152* | |

| Experience | −0.130* | 0.166* | 0.592† | −0.152* | |

Statistical significance at

p < 0.05,

p< 0.001.

Hospital setting; non-psychiatric setting vs. psychiatric setting, Age; 25–35 years vs. 36–45 years vs. 46 years and above, Gender; male vs. female, Experience; less than or equal to 5 years vs. above 5 years.

Genderwise, females expressed significantly higher stigmatizing attitudes towards mentally ill patients compared to male health professionals (BE 2.08 vs. 1.95, p=0.009; CAMI 2.49 vs. 2.39, p=0.008). A very weak association was also obtained for the female gender and stigmatization (r = 0.157, p=0.008), so also with younger age of the health professionals (r= −0. 214, p=0.034).

The years of experience of health professionals produced some significant results on two CAMI constructs. Stigmatizing responses from health professionals with less experience (less than or equal to 5 years) were significantly higher with the SR (2.37 vs. 2.23, p=0.0180) and CMHI constructs (2.69 vs. 2.52, p=0.0350) compared to those with higher experience (above 5 years). Overall responses on the CAMI instrument showed health professionals with less experience being more stigmatizing (2.49 vs. 2.41, p=0.0310). Correlation results also produced a weak association of less experience and higher tendency to stigmatize (r = −0.130, p=0.0310) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study evaluated the attitudes of health professionals towards the psychiatrically ill patient. Its findings suggest that stigmatization attitudes do exist among the doctors, pharmacists, and nurses towards the mentally ill patients.

The primary goal of health professionals is to provide care irrespective of their personal circumstances and preferences. Negative attitudes towards psychiatric patients by Nigerian health workers may be due to deeply-rooted negative cultural beliefs and traditional acts that result in a societal dislike for such patients (14). The findings of this study support the previous work of researchers (15–16) who showed that healthcare professionals share negative attitudes towards mental illness, similar to the attitudes of the general public. Some studies have also reported these stigmatizing attitudes not just among health professionals but also among health professionals who have direct contact with patients with mental illness (3,17). In other research works, scholars found that health professionals harbored some of the same types of stigmas exhibited by the general population (18–19).

The stigmatizing attitudes expressed in the authoritarianism construct refers to the view of the mentally ill person as someone inferior who requires coercive handling, and health professionals disagreed with the positive statements and agreed with the negative ones. This suggests that health workers in these hospitals believe that the mentally ill are inferior. Specifically, stigmatization was highest with the statements “Mental hospitals are an out-dated means of treating the mentally ill” and “There is something about the mentally ill that makes it easy to tell them from normal people”. This further suggests that these health professionals also discriminate the psychiatric ill from qualitative care, both from physical structures to societal adjustment.

Social restrictiveness explores fear and exclusion of people with mental illness, and a smaller proportion of our respondents agreed with the positive statements and disagreed with the negative ones. However, only one key statement under this construct produced a more pronounced stigmatizing attitude from the majority (51.3%) of the respondents: “Most women who were once patients in a mental hospital can't be trusted as babysitters”. We think this might be due to the perceptions that there is a tendency for the mental illness recurring or that mental illness might also be “transmitted to the child through a learned process”. In contrast, however, these health professionals did not agree with that generally those mentally ill patients were very dangerous to the society than is supposed by other people.

The majority of our respondents showed a paternalistic and sympathetic view of the mentally ill patients further reflecting favorable attitudes towards such such patients. This finding supports the previous work of Barke and collaborators in Ghana, who showed that regarding the society's attitude towards the mentally ill patients, benevolent views tended to prevail and the responsibility of providing the best possible care was acknowledged by a large majority (20).

The pharmacists' stigmatizing attitudes seen in this study could be attributed to lack of space for patient counseling in hospitals and continued resistance by physicians towards the implementation of pharmaceutical care. Absence of these could limit the pharmacist's access to patients, reduced communication with the patients and inadequate inter-professional collaborative care opportunities with other members of the health care team. Since the pharmacists also perceived a lack of adequate undergraduate training in mental health, these differences may indicate an increased level of discomfort in a therapeutic area in which they are undertrained. Also, there are currently no schools of pharmacy in the country conducting clinical rotations for students in psychiatric facilities. This further widens the communication and competency divide between the mentally ill patient and the pharmacist. In order to improve pharmacists' ability to meet the health and drug-related needs of its population, there should be increased awareness of the potential stigmatizing behaviors towards the mentally ill in pharmacy practice. This can be achieved by conducting well-guided anti-stigma seminars and patient simulated meetings to pharmacists as suggested in other studies (21).

The existence of stigmatization of the psychiatric ill among doctors has also been reported in other studies among medical students who reported unfavorable attitudes towards the mentally ill (22). Lack of adequate information about mental illness, absence of training and lack of contact with individuals with mental illness might be some of the most important reasons for these negative attitudes. If the physicians' attitudes towards people with mental illness are not better than that of the public, then they may not serve as worthy role models or opinion leaders in anti-stigma campaigns (9).

An interesting finding in this study was that health professionals working directly with mentally ill patients showed more positive attitudes than those who did not, and this was in line with previous research (23). This could be related to the increased contact they have with these patients and, of course, due to the fact that helping people with mental health problems is their duty. Contact with people with mental illness seems to be a stronger predictor of less stigmatizing attitude towards mental illness, as perceived danger and desired social distance decrease with increasing contact (24). In contrast, however, a recent study reported that there was no significant association between the familiarity of a health professional with mental illness and positive attitudes towards the mentally ill (25).

The years of experience of health professionals irrespective of profession and age produced some significant results. As one continues to work in the medical profession and is exposed to various patients and disease conditions, there is a tendency for such health professional to develop an accepting and tolerant attitude towards these patients. Also, health professionals with more years of experience tend to have greater awareness and knowledge of these diseases and thus might exhibit better attitude towards them.

The findings from this study highlight the need to continually explore the types and determinants of attitudes in the delivery of healthcare to the psychiatric ill patients. Further exploration into other similar settings as used in this study will be a good start in trying to reduce stigmatizing attitudes towards the psychiatric ill among health professionals.

This study suffered some limitations. As with other studies that assess perception towards social issues, respondents might have completed the survey with positive responses so as to be seen as morally right. We, however, hope that the promise of anonymity would have reduced this bias. Secondly, the reader is also cautioned in generalizing the attitude scores to other health professionals who did not participate in this study, though they were smaller in population. Thirdly, the classification of respondents into non-stigmatizers and stigmatizers in this study using the arbitrary choice of a cut-off point of 3.0 for each dimension's mean scores should be treated with caution. While this might not be a gold standard for the CAMI scale, the use of other cut-off points (e.g. median score) could alter the interpretations of the results of this study. Lastly, the low response rate seen among the health professionals surveyed and some poorly represented population subsets in this study could have affected the strength of the results.

In conclusion, the level of stigmatization among Nigerian health professionals is low in these two hospital settings. Being a pharmacist, a female health professional and working in a non-psychiatric hospital were all associated with stigmatizing attitudes towards mentally ill patients. Health professionals should be explicitly aware of the impact their perceptions and eventual judgment of disadvantaged groups can have in their caring role.

References

- 1.Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA. The impact of mental health stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Pub Int. 2014;15:37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Mental Health, author. U.S. leading categories of diseases/disorders. Bethesda (MD): NIMH; 2015. [28 August, 2016]. [Internet] Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/disability/us-leading-categories-of-diseasesdisorders.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crisp A, Gelder M, Rix S, Meltzer H, Rowlands O. Stigmatisation of people with mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Link B, Struening E, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan J. The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psych Serv. 2001;52:1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlick D, Rosenheck R, Clarkin J, Sirey J, Salahi J, Struening E, et al. Adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psych Serv. 2001;52:1627–1632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graf J, Lauber C, Nordt C, Rüsch P, Meyer PC, Rossler W. Perceived stigmatization of mentally ill people and its consequences for the quality of life in a Swiss population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:542–547. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000135493.71192.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. The stigma of psychiatric treatment and help-seeking intentions for depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259:298–306. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0870-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrini C. Mental illness stigma in healthcare settings a barrier to care. CMAJ. 2014;186:1. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adewuya AO, Oguntade AA. Doctor's attitudes towards people with mental illness in Western Nigeria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:931–936. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartorius N, Gaebel W, Cleveland HR, et al. WPA guidance on how to combat stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:131–144. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audu IA, Idris SH, Olisah VO, Sheikh TL. Stigmatization of people with mental illness among inhabitants of a rural community in northern Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:55–60. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack-Ide IO, Uys L. Barriers to mental services utilization in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: services users' perspectives. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:159. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.159.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor SM, Dear M. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7:225–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ewhrudjakpor C. Knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of health care providers towards the mentally ill in Delta State, Nigeria. Ethno Medicine. 2009;3:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volmer D, Maesalu M, Bell JS. Pharmacy students' attitudes toward and professional interactions with people with mental disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:402–413. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Law GU, Rostill-Brookes H, Goodman D. Public stigma in health and non-healthcare students: attributions, emotions and willingness to help with adolescent self-harm. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:342–346. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rossler W. Factors influencing social distance towards people with mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40:265–274. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000026999.87728.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordt C, Rossler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:709–714. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barke A, Nyarko S, Klecha D. The stigma of mental illness in Southern Ghana: attitudes of the urban population and patients' views. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;46:1191–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Economuo M, Peppou LE, Stefanis CN. Medical students' beliefs and attitudes towards schizophrenia before and after undergraduate psychiatric training in Greece. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2012;66:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Issa BA, Adegunloye OA, Yussuf AD, Oyewole OA, Fatayo FO. Attitudes of medical students to psychiatry at a Nigerian medical school. Hong Kong J Psychiatr. 2009;19:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjokman T, Angelman T, Jonsson M. Attitudes towards people with a mental illness: a cross-sectional study among nursing staff in a psychiatric and somatic care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22:170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712-2007-00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander LA, Link BG. The impact of contact on stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness. JMH. 2008;12:271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 25.James BO, Omoaregba JO, Okogbenin ES. Stigmatization attitudes towards persons with mental illness: a survey of medical students and interns from Southern Nigeria. Mental Illness. 2012;4(8):32–34. doi: 10.4081/mi.2012.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]