Abstract

Background

Neonatal mortality rates in Ethiopia are among the highest in the world. Reducing neonatal and young infant mortality highly relies on early recognition of symptoms and appropriate care-seeking behavior of parents/care givers. The main aim of this study was to assess the knowledge of danger signs and health seeking behavior of parents/care givers in newborn and young infant illness in Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted using cluster sampling technique to get 422 samples of parents/care givers who had infants of less than 6 month old. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaire. Logistic regression was used to identify factors affecting care seeking behavior and knowledge of parents/care givers on newborn and young infant illness.

Result

Care seeking behavior for newborn and young infant illness was high (83%), the major factor associated with care seeking behavior being place of delivery. Only less than half of the respondents had adequate knowledge of symptoms of illness of newborns and young infants. The major factors associated with knowledge of parents/care givers were maternal education and paternal education.

Conclusions

To improve the knowledge of parents/care givers about newborn and young infant illness, counseling about the major symptoms of newborn and young infant illness should be intensified.

Keywords: Neonatal illness, care seeking behavior, new born, knowledge

Introduction

The neonatal period (the first 28 days of life) is the most critical period for the survival of a child. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, every year, over 4 million babies die during the neonatal period globally; 98% of the deaths occurring in the developing world (1).

This report shows that, in developing countries, the risk of death in the neonatal period is six times greater than in developed countries and in the least developed countries; it is over eight times higher. Globally, 2.7 million deaths, or roughly 45% of all under-five deaths, occur during the first 28 days of life. Of these, almost 1 million neonatal deaths occur on the day of birth and close to 2 million die in the first week of life (2). Each year in Africa, around 1.16 million babies die in their first month; among this, half of them die on their first day of life. Sub-Saharan Africa, where about a third of under-five deaths occur during the neonatal period, have the highest neonatal mortality rate (31 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2013) and account for 39% of global neonatal deaths. In Ethiopia, according to EDHS 2016, the neonatal mortality rate was 29 per 1000 live births (2).

With the introduction of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), remarkable progress has been made worldwide to reduce childhood mortality. Ethiopia was one of the countries which met the target for MDG 4 on child survival three years ahead of time, as the under-five mortality rate has declined by two-thirds from the 1990 figure of 204/1,000 live births to 68/1,000 live births in 2012. Despite this remarkable achievement, the mortality data by age reveals that the decline in neonatal mortality is not as impressive as the infant and child mortality rates. It has fallen only by 42% during the same period; from 54/1000 live births in 1990 to 28/1000 live births in 2013. About 44% of the childhood deaths occur within the first 28 days of life, thus increasingly accounting for a larger proportion of the under-five deaths (3).

Reducing the neonatal and infant mortality has been recognized as both the global and national public health challenge, where Ethiopia is not an exception. According to Save the Children report in 2012, the global contributors to neonatal death were preterm birth complications (34%), intrapartum-related complications (24%), sepsis/meningitis (12%), pneumonia (10%), congenital abnormalities (9%), tetanus (2%), diarrhea (2%) and others (6%).

Neonatal illnesses exhibit a rapid course of progression and can prove to be fatal if not identified and treated correctly and timely. Studies suggest that universal coverage of basic essential interventions could reduce neonatal deaths by an estimated 71% (5). Timely and adequate care seeking for illnesses as well as appropriate and timely intervention are therefore key elements in improving neonatal health and survival (6,7,8).

Different tools have been introduced to the health programs of many countries including Ethiopia to facilitate early identification and management of neonatal illnesses. One of these programs is the Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) developed by WHO, one of the focuses being assessment of neonatal danger signs and providing prompt timely treatment (9). Using this strategy, health workers are trained to assess, classify and provide appropriate treatment for sick newborns and young infants, as well as provide counseling for the mothers about the treatment and the cares of the sick newborns and young infants (10). However despite the availability of these lifesaving interventions in the health facilities, inadequate care seeking is still being reported for illnesses of newborns and young infants (10,11).

Timely and appropriate care seeking for neonatal illnesses depend partly on parents'/care givers' recognition and perception of danger signs in the neonates (14). Neonatal deaths can be avoided by implementing simple and affordable interventions, especially in areas with weak health systems and high rates of newborn mortality. Previous studies have shown that health education to improve home-care practices, recognition of newborn danger signs, demand creation for care by skilled care providers and increased parents'/care givers' health seeking behavior can lead to significant reductions in newborn mortality (15). Other studies have also demonstrated that if newborn danger signs are not recognized and are left untreated, they can lead to higher rate of complications and increased morbidity and mortality (15).

Therefore, the objectives of this study were: 1) to determine the level of parents'/care givers' knowledge on neonatal danger signs, 2) to determine the factors associated with parents'/care givers' knowledge and 3) to assess parents'/care givers' care seeking behavior for newborn and young infants' illnesses.

Materials and Methods

Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted on parents/caregivers who had infants of less than 6 months old in Tiro Afeta District, Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia, about 350Km to the Southwest of the capital, Addis Ababa. Parents /caregivers who were critically ill and were unable to provide response during data collection period were excluded from the study.

The total sample size of the study was determined by using single population proportion formula by assuming 5% level of significance, 5% margin of error and taking 50% proportion of good maternal knowledge on neonatal danger signs. After considering cluster effect of six and10% non-response rate, the final sample size obtained was 422. Cluster sampling technique was employed to select eligible sampled population. In the study area, there were 6 clusters based on the nearby health centre, one cluster having one health centre and 5 kebeles, the smallest administrative unit. The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated to each cluster.

Structured self-administered and pre-tested questioner adopted from different literatures was employed for data collection. The questioner included parents'/care givers' knowledge about neonatal danger signs, socio-demographic characteristics, obstetric characteristics and health seeking behavior. The questionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated into local language (Afaan Oromo) and back to English by different language experts to check consistency of the data. Data collection was performed by trained nurses and supervision was done during the data collection by one BSc Health Officer.

The collected data was cleaned, coded and entered into EPI data version 3.1 computer programs. The data was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20, and then recoded, categorized and sorted for further analysis. Descriptive statistics was used to describe the characteristics of the study participants. Additionally, bi-variable and multivariable analysis were done to identify the factors affecting the care seeking behavior and knowledge of parents/care takers with regard to illnesses in newborn and young infants. Percentages, frequency distributions, cross tabulations and graphs were used to describe the study population in relation to relevant variables in the study. To assess parents'/care takers' knowledge, we assessed the mother's/care taker's knowledge for around 13 common symptoms of newborns and young infant illnesses. We then calculated the mean to categorise the mother's knowledge into adequate and inadequate. Furthermore, logistic regression, specifically bi-variable and multivariable analysis were used to identify factors associated with care seeking behavior for newborn and young infant illness.

Independent variables with p-value less than 0.05 and odds ratio (crude and adjusted odds ratios) with 95% confidence intervals were considered as having significant association with the dependent variable. All independent variables which had significant associations on bi-variable analysis with p-value less than 0.25 were included in multiple backward logistic regression model in order to assess the independent predictors of care seeking behavior of newborn and young infant illness. Finally, p-value < 0.05 was considered to declare a result as statistically significant in this study.

Ethical clearance was obtained from Jimma University, College of Health Sciences, and letter of permission was obtained from Jimma Zone Health Department as well as Tiro Afata Health Office. Verbal consent was obtained from the parents/care givers of the infants.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics of parents/caretakers and their infants: In this study, a total of 400 parents/caregivers participated in the study giving a response rate of 94.7%. The majority of the respondents were between the ages of 25–34 years (55.4%), followed by age between 18–24 years (26.8%) (Table 1). The majority were Muslims (80.5%) followed by Orthodox Christians (14.3%). Most of the mothers were illiterate which is 64%, while only 7.5% of the respondents had completed secondary school and above. The majority of the infants were between the ages of 9–24 weeks (38.8%) followed by those aged between 5–8 weeks (32.3%), and only 5.5% were aged less than 1 week during the study period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents in Tiro Afeta District, Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia (n=400), 2016

| Variable (n=) | Frequency | % |

| Age of care givers | ||

| 18–24 | 107 | 26.8 |

| 25–34 | 222 | 55.5 |

| 35–44 | 69 | 17.3 |

| 45+ | 2 | 0.5 |

| Religion | ||

| Muslim | 322 | 80.5 |

| Orthodox | 57 | 14.3 |

| Protestant | 21 | 5.3 |

| Maternal Educational Status | ||

| Cannot read and write | 256 | 64.0 |

| Primary education(1–8) | 114 | 28.5 |

| Secondary school & above | 30 | 7.5 |

| Paternal Educational status | ||

| Cannot read and write | 241 | 60.25 |

| Primary education (1–8) | 115 | 28.75 |

| Secondary school & above | 44 | 11.0 |

| Maternal Occupation | ||

| Government employee | 24 | 6.0 |

| Self-employee & daily laborer | 35 | 8.8 |

| Farmer | 152 | 38.0 |

| House wife | 189 | 47.25 |

| Paternal Occupation | ||

| Government employee | 36 | 9.0 |

| Self-employee&daily laborer | 80 | 20.0 |

| Farmer | 284 | 71.0 |

| Maternal Marital Status | ||

| Married | 385 | 96.3 |

| Single | 10 | 2.5 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.5 |

| Divorced | 3 | 0.8 |

| Paternal Income (monthly) | ||

| <500 | 201 | 50.25 |

| 500–1500 | 128 | 32.0 |

| >1500 | 71 | 17.75 |

| Family size | ||

| <3 | 56 | 14.0 |

| 3–5 | 138 | 34.5 |

| >5 | 206 | 51.5 |

| Parity | ||

| <3 | 184 | 46.0 |

| 3–5 | 142 | 35.5 |

| >5 | 74 | 18.5 |

| Infant Age | ||

| 0–1 week | 22 | 5.5 |

| 2–4 weeks | 94 | 23.5 |

| 5–8 weeks | 129 | 32.3 |

| 9–24 weeks | 155 | 38.8 |

| Infant Sex | ||

| Male | 179 | 44.8 |

| Female | 221 | 55.3 |

Health service characteristics: As we can see from Table 2, the majority of the respondents (78.8%) had ANC follow-up during their pregnancy. Among the mothers who had ANC follow-up, 71.5% got ANC counseling services, while 49.5% were advised about immunization and only 15% were advised about new-born illnesses. Similarly, 89% of the study participants reported that they had PNC visits after delivery, out of which 63.5% and 38.8% were advised about breastfeeding and newborn illnesses respectively. The majority of the mothers delivered their last children at health center (67.5%) while only 6.6% delivered at home.

Table 2.

Health Services Characteristics of (33.8%) followed by lack of enough money mothers in Tiro Afeta District, Jimma Zone, South (30.9%). West Ethiopia (n=400), 2016

| Variable | Frequency | % |

| ANC follow up | ||

| No | 85 | 21.3 |

| Yes | 315 | 78.8 |

| ANC counseling service | ||

| No | 90 | 28.5 |

| Yes | 225 | 71.5 |

| Type of counseling during ANC | ||

| Birth preparedness | 115 | 28.8 |

| Danger sign of Pregnancy | 57 | 14.3 |

| New-born illness | 62 | 15.5 |

| Breast feeding | 141 | 35.3 |

| Immunization | 198 | 49.5 |

| PMTCT | 27 | 6.8 |

| Maternal Nutrition | 181 | 45.2 |

| Harmful substance | 34 | 8.5 |

| Personal Hygiene | 57 | 14.3 |

| Others | 18 | 5.5 |

| PNC Attendance | ||

| No | 43 | 10.8 |

| Yes | 357 | 89.2 |

| Type of PNC counseling | ||

| New-born illness | 135 | 33.8 |

| Breast feeding | 254 | 63.5 |

| Immunization | 248 | 62.0 |

| Nutrition | 200 | 50.0 |

| Personal Hygiene | 70 | 17.5 |

| Others | 51 | 12.7 |

| Place of Delivery | ||

| Home | 26 | 6.5 |

| Health post | 19 | 4.75 |

| Health center | 270 | 67.5 |

| Hospital | 85 | 21.3 |

Care seeking behavior and reason for not taking to health facility: Table 3 shows the care seeking behavior of parents/caregivers on neonatal and young infant illness. The majority (92.8%) of the parents/care givers reported that they take their infants to the health center, and that both the mother and father decide where to seek care during illness. Among parents/caregivers who do not take their infants to health facilities, the major reasons mentioned were high treatment cost (33.8%) followed by lack of enough money (30.9%).

Table 3.

care seeking behavior of parents/caregivers on neonatal and young infant illness in Tiro Afeta District, Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia, 2016

| What do you do when a newborn/young infant is sick? |

# | % |

| Take to health post | 70 | 17.5 |

| Take to health center | 371 | 92.8 |

| Take to hospital | 9 | 2.2 |

| Call HEW | 4 | 1.0 |

| Take to traditional healer | 13 | 3.2 |

| Give home remedies | 48 | 12.0 |

| Take to spiritual healer | 2 | 0.5 |

| Do nothing/take no action | 5 | 1.2 |

| Reason for not taking to health facility? | ||

| Illness was not serious | 3 | 4.4 |

| Had no enough money | 21 | 30.9 |

| Long distance to health facility | 3 | 4.4 |

| Busy | 4 | 5.9 |

| High Treatment cost | 23 | 33.8 |

| Health workers are hostile | 5 | 7.4 |

| Considering that Herbs are more | 9 | 13.2 |

| effective | ||

|

Who decides where to seek care when an infant is sick |

||

| Mother alone | 89 | 22.3 |

| Father alone | 2 | 0.5 |

| Both | 309 | 77.3 |

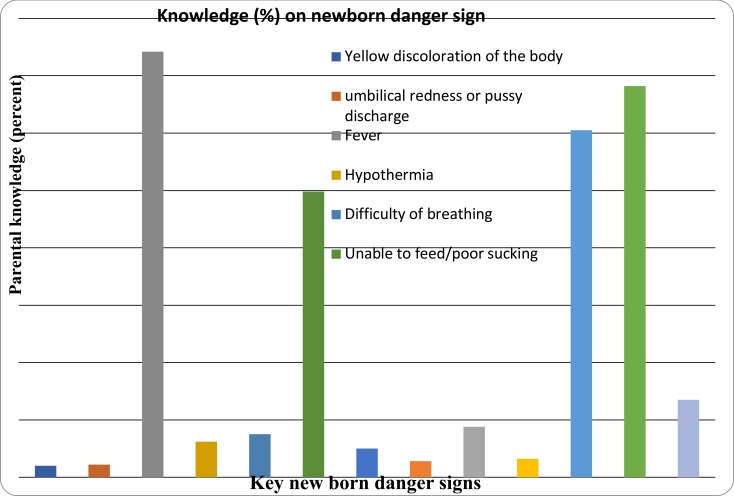

Maternal/care taker's knowledge of symptoms: Among the 13 symptoms of illnesses of newborns and young infants assessed, the commonest identified symptoms by the mothers/care takers were fever (74.3%), diarrhea (68.3%), vomiting (60.5%) and poor feeding (49.8%). The least identified symptoms were yellowish discoloration of the body (2%), umbilical discharge/redness (2.3%), altered consciousness (2.8%) and convulsion/abnormal body movement (5%). When we tried to categorize the maternal/care taker's knowledge into adequate and inadequate based on the calculated mean, which was equivalent to 3 symptoms, almost two-third (65.3%) of the mothers/care takers had inadequate knowledge, which means that they were unable to mention more than three symptoms among the 13 symptoms of illness of newborns and young infants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Maternal/care givers' knowledge of symptoms of illness in newborns and young infants

Factors associated with knowledge of mothers/care givers on newborn and young infant illness: Tables 4 and 5 show bivariate analysis for factors affecting knowledge and care seeking behavior of parents/care givers on newborn and young infant illness respectively. Among the ten factors which fulfilled the assumption of logistic regression, 6 variables with p-value <0.25 (maternal occupation, paternal occupation, maternal education, paternal education, income and ANC attendance) were selected for the final mode. When controlled for possible confounding effects of other covariates that showed association with newborn and young infant illness on bivariate analysis, maternal occupation was significantly associated with knowledge of newborn and young infant illness with AOR 0.160 and 95% CI (0.361, 0.693). On the other hand, fathers whose monthly incomes were more than 1,500 Birr had also better knowledge of newborn and young infant illness with AOR 3.258 and 95% CI (3.258, 6.537). Among the 12 variables which were entered into the bivariate model, only one variable (place of delivery) was a significant predictor of care seeking behavior.

Table 4.

Bivariate analysis for factors affecting knowledge of parents/care givers on neonatal and young infant illness in Tiro Afeta District, Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia

| Variable | Frequency | COR (95%CI) | p-value |

| Age | |||

| 16–24 | 107(26.75%) | ||

| 25–34 | 222(55.5%) | .982(.608,1.587) | .942 |

| >35 | 71(17.7) | .684(.357,1.310) | .252 |

| Maternal Occupation | |||

| Government employee | 24(6%) | ||

| Self-employee and Daily labourer | 35(8.7%) | .222(.071,.698) | .010 |

| Farmer | 152(38%) | .159(.059,.424) | .000 |

| House wife | 189(47.25%) | .148(.056,.391) | .000 |

| Paternal Occupation | |||

| Government employee | 36(9%) | 0.00 | |

| Self-employee and daily labourer | 80(20%) | .309(.134,.714) | .006 |

| Farmer | 284(71%) | .176(.083,.373) | .000 |

| Maternal education | |||

| No education | 256(64%) | ||

| Primary school | 114(28.5%) | 2.669(1.685,4.229) | .000 |

| Secondary school and above | 30(7.5%) | 2.765(1.283,5.956) | .009 |

| Paternal education | |||

| No education | 241(60.25%) | ||

| Primary school | 115(28.75%) | 2.240(1.398,3.587) | .001 |

| Secondary school | 44(11%) | 6.464(3.215,12.996) | .000 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married and living together | 385(96.25%) | ||

| Single and not living together | 15(3.75%) | .746(.412,4.354) | .626 |

| Income | |||

| ≤500 | 201(50.25%) | 0.00 | |

| 500–1500 | 128(32%) | 2.242(1.386,3.6265) | .001 |

| ≥1500 | 71(17.75%) | 4.228(2.387,7.487) | .000 |

| Family Size | |||

| <3 | 56(14%) | ||

| 3–5 | 138(34.5%) | .899(.467,1.693) | .720 |

| >5 | 206(51.5%) | .858(.465,1.584) | .624 |

| ANC follow up | |||

| No | 85(21.25%) | ||

| Yes | 315(78.75%) | 4.605(2.351,9.018) | .000 |

Table 5.

Bivariate analysis for factors affecting care seeking behavior of parents/care givers on neonatal and young infant illness in Tiro Afeta District, Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia

| Variable | COR (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Age | |||

| 16–24 | 107(26.75%) | ||

| 25–34 | 222(55.5%) | .957(.515,1.778) | .889 |

| >35 | 71(17.7) | 1.214(.560,2.632) | .623 |

| Maternal Occupation | |||

| Government employee | 24(6%) | ||

| Self-employee and Daily labourer | 35(8.7%) | 1.750(.404,7.581) | .454 |

| Farmer | 152(38%) | 2.094(.590,7.436) | .253 |

| House wife | 189(47.25%) | .970(.268,3.509) | .970 |

| Paternal Occupation | |||

| Government employee | 36(9%) | ||

| Self-employee and daily labourer | 80(20%) | 1.061(.371,3.029) | 0.912 |

| Farmer | 284(71%) | 1.017(.401,2.577) | 0.972 |

| Maternal education | |||

| No education | 256(64%) | ||

| Primary school | 114(28.5%) | .938(.521,1.689) | .831 |

| Secondary school and above | 30(7.5%) | .721(.240,2.169) | .561 |

| Paternal education | |||

| No education | 241(60.25%) | ||

| Primary school | 115(28.75%) | 1.225(.688,2.183) | .490 |

| Secondary school | 44(11%) | 0.980(.407,2.357) | .964 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married and living together | 385(96.25%) | ||

| Single and not living together | 15(3.75%) | 1.231(.338,4.484) | .753 |

| Income | |||

| ≤500 | 201(50.25%) | ||

| 500–1500 | 128(32%) | 1.353(.741,2.472) | .325 |

| ≥1500 | 71(17.75%) | 1.945(0.990,0.990) | .054 |

| Family Size | |||

| <3 | 56(14%) | ||

| 3–5 | 138(34.5%) | 1.017(.419,2.466) | .970 |

| >5 | 206(51.5%) | 1.446(.634,3.297) | .381 |

| ANC follow up | |||

| No | 85(21.25%) | ||

| Yes | 315(78.75%) | .773(.420,1.422) | .408 |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Home | 26(6.5%) | ||

| Health centre/health post | 289(72.25%) | .303(.129,.709) | .006 |

| Hospital | 85(21.25%) | .263(.097,.714) | .009 |

Discussion

Care seeking for common newborn and young infant illness from health institution has a great potential to reduce newborn and young infant mortality (4). In this study, the majority of the parents/caregivers (83%) took their newborn /young infant to health facility during illness which is much higher than the finding of a similar study done in rural Tanzania, where the majority of the respondents (73%) did not take their neonates to health facilities during illness (16).

The findings of this study show that the common reasons for non-utilization of health facilities were the high cost of treatment, unavailability of qualified health providers and lack of enough money. This is similar to the study done in Edo State of Nigeria, where the major reason was treatment cost 41% (17). This might possibly be because the majority of the family had monthly incomes of less than 500 Birr.

From this study, maternal knowledge about symptoms of newborn and young infant illness, which is one of the crucial factors affecting the care seeking behavior of parents, had been found to be low, demonstrated by the fact that only less than 50% of the mothers had adequate knowledge about newborn and young infant illness. This is similar to the report of Alex Hurt (18) who found poor awareness of danger signs amongst caregivers in Niger. It, however, differs from the high level of awareness of newborn danger signs in India reported by Awasthiet (10) and Dongre (19). Besides, symptoms of serious illness in the newborn and young infants which are easy to detect were poorly recognized by parents in this study (49.8% for poor feeding, 5% for abnormal body movement, 2.8% for altered consciousness and 2% for yellowish discoloration of the body). Additionally, the proportion of mothers who received counseling about the newborn and young infants illnesses during ANC and PNC was low (15% and 38.8% respectively). These might indicate the need to improve the counseling given to mothers during ANC and PNC giving due emphasis to these symptoms of serious illness, given the fact that the majority of the mothers are having ANC/PNC follow-up and are delivering at health facilities.

The main factors influencing knowledge of parents/caregivers about newborn and young infant illness identified in this study were ANC follow-up, educational status of mother and father, occupation of both mother and father and monthly income. This finding is partly consistent with a study done in Gondar, North West Ethiopia, which showed that mothers' education is an important determinant factor for knowledge of new born and young infant illness (20). Mothers having secondary and above educational level increased the odds of their knowledge by nearly three times. Similarly, paternal education was a significant predictor of good knowledge about neonatal and young infant illness. The odds of having knowledge about newborn and young infant illness was 6 times among fathers who achieved secondary and above educational level. Mothers having antenatal care were 4 times more likely to know about new born and young infant illness compared to their counterparts. This could demonstrate that having ANC follow-up creates a good opportunity to get the necessary information about newborn and young infant illness, even though the finding is different from the study conducted in Uganda (21).

Although Ethiopia has taken a great initiative to empower the community to improve neonatal and infant health services at the grass root level, in this study, parents'/care givers' knowledge level about newborn and young infant illness, which is a key entry point to improve neonatal health, was found to be low, despite the high care seeking behavior for new born and young infant illness. It was particularly low for some of the symptoms of serious illnesses, like jaundice, in the newborn and young infants. Thus, intervention modalities focusing on maternal/parental counseling on the commonest symptoms of illness in the newborn and young infants particularly during the ANC/PNC follow-up as well as during institutional delivery is very important in order to increase parents'/care givers' knowledge of recognition of illness and hence improve care seeking behavior of parents/care givers.

The fact that the parents/care takers reported that the majority of them take their sick newborns and young infants to health facilities (i.e. high care seeking behavior) may not be the real practice of the parents/care givers. It might be due to the respondents' socially desirable response.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Jimma University, College of Health Sciences and JUCAN research project for financially supporting this study. We would also thank all the parents/care-givers and all other individuals who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Neonatal and Perinatal Mortality Covering, Regional and Global Estimates. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. Addis Ababa, Calverton: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Newborn and Child Survival Strategy Document Brief Summary 2015/16-2019/20 FMOH/MCH

- 4.Ensuring every baby survives. 1 St John's Lane, London EC1M 4AR, UK: 2014. Save the Children; Ending Newborn Deaths. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickson KE, Simen-Kapeu A, Kinney MV, et al. Every Newborn: health-systems bottlenecks and strategies to accelerate scale-up in countries. The Lancet. 2014;384:438–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60582-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amarasiri de Silva MW, Wijekoon A, Hornik R, Martines J. Care seeking in Sri Lanka: one possible explanation for low childhood mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:1363–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Souza RM. Role of health-seeking behavior in child mortality in the slums of Karachi, Pakistan. J Biosoc Sci. 2003;35:131–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, Bellagio Child Survival study group How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362:657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young Infants Clinical Signs Study Group, author. Clinical signs that predict severe illness in children under age 2 months. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):135–142. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awasthi S, Verma T, Agarwal M. Danger signs of neonatal illnesses: Perceptions of caregivers and health workers in North India. Bull WHO. 2006;84:1–8. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.029207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava NM, Awasthi S, Mishra R. Neonatal morbidity and care seeking behavior in Urban Lucknow. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawn JE, Kinney MV, Black RE, et al. Newborn survival: a multi-country analysis of a decade of change. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(suppl 3):iii6–iii28. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, author. Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. Addis Ababa, Calverton: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill Z, Kendall C, Arthur P, Kirkwood B, Adjei E. Recognizing childhood illnesses and their traditional explanations: exploring options for care-seeking interventions in the context of the IMCI strategy in rural Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:668–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darmastadt G L, Bhutta Z A, Cousens S, et al. Evidence based cost effective interventions; how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mrisho M, Schellenberg D, Manzi F, et al. Neonatal Deaths in Rural Southern Tanzania: Care-Seeking and Causes of Death. IntSch Res NetwPediatr. 2012;7:1–8. doi: 10.5402/2012/953401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aigbokhaode AQ, Isah EC, Isara AR. Health seeking behavior among caregivers of under five children in Edo State, Nigeria. SEEJPH. 2015;12:235–224. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alex-Hart BA, Dotimi DA, Opara PI. Mothers' recognition of newborn danger signs and health seeking behavior. Niger J Paed. 2014;41(3):199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. A Community Based Approach to Improve Health Care Seeking for Newborn Danger Signs in Rural Wardha, India. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigatu SG, Worku AG, Dadi AF. Level of mother's knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors in North West of Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1278-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandberg J, OdbergPettersson K, Asp G, Kabakyenga J, Agardh A. Inadequate knowledge of neonatal danger signs among recently delivered women in Southwestern Rural Uganda:a community survey. PLoSOne. 2014;9(5):e97253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]