Abstract

Background

Burnout is a common syndrome seen in healthcare workers, particularly physicians who are exposed to a high level of stress at work. Therefore, this study assessed the level of burnout and its associated factors among physicians working in public hospitals of Southern Ethiopia.

Methods

Institution based cross-sectional study was conducted using structured self-administered questionnaire from March 13 to April 11, 2017. Maslach's Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey was used to measure burnout level of physicians. Data were entered in to Epi Data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 21 software. Descriptive statistics, bi-variate and multivariable linear regression analysis were performed. P-value less than 0.05 was used to determine association between independent and dependent variables.

Result

Burnout level was measured in three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment with mean scores of 27.2, 12.93 and 25.06, respectively. Age, receiving recognition from hospital managers and monthly salary were negatively associated; and number of patients observed per week was positively associated with emotional exhaustion. Age, working in primary hospital, having support from family and organization, monthly salary and professional training were negatively associated with depersonalization. Monthly salary was positively associated and working in primary hospital was negatively associated with personal accomplishment.

Conclusion

Burnout was found in a high level among physicians in this study. Receiving recognition from hospital managers, age, working in primary hospital, monthly salary, having support from family and organization, professional training and the number of patients observed per week can possibly affect the level of burnout.

Keywords: Burnout, Physicians, Public Hospitals, Southern Ethiopia

Introduction

Burnout is a psychological term for the experience of long-term exhaustion and diminished interest. Despite this, burnout is not a recognized disorder in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (1). It was first described in the mid-1970s by Freudenberg, and ever since, it has been the subject of many studies (2). Burnout is considered as an epidemic of modern society and the issue of occupational stress. The emphasis of burnout is now increasing worldwide. Burnout focuses on specific stressors in the workplace and the environmental pressures affecting the health of employed people (3). Healthcare workers are exposed to high levels of distress at work. Persistent tension can lead to exhaustion as well as psychological and/or physical distress. Moreover, burnout syndrome can have an effect on employee satisfaction, medical errors, work productivity, mental and physical health, rates of absenteeism and staff turnover, and it can affect family roles and functions (4,5).

Burnout has three interrelated dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and low personal accomplishment (PA). Prolonged exposure to stress is usually the main cause of emotional exhaustion, and it manifests through the loss of enthusiasm for work, feeling helpless, trapped and defeated. Depersonalization occurs when physicians treat patients indifferently, objectify them, and develop a negative attitude towards their colleagues and profession. Inefficiency, or the lack of a sense of personal achievement, is characterized by the individual's withdrawal from responsibilities and detachment from the job (6).

From developed countries' contexts, severe burnout syndrome was presented in 25% – 70% of physicians (7). In relation to developing countries' contexts, high level of burnout syndrome was also reported among healthcare professionals. For example, from Africa, up to two thirds of healthcare workers suffer from burnout, mostly due to emotional exhaustion (8).

The modern medical workplace is a complex environment, and physicians' responses to it vary greatly. Some find it stimulating and exciting, whereas others become stressed and burned out from their heavy workload. Several personal, interpersonal and organizational factors have been reported to be related to job satisfaction, stress and burnout in the medical environment (9–12).

Estimate of burnout in physicians often yields high figures and varies between countries, across time or specialties. This variation is understandable and expected because burnout is related to stressors arising from work environment which is influenced by these variables. A study from rural British Columbia reported that 80% of physicians suffered from moderate to severe Emotional Exhaustion, 61% suffered from moderate to severe Depersonalization, and 44% had moderate to low feelings of Personal Accomplishment (13).

Most of the countries in the world are already facing physicians' deficit and if the physician burnout continues, risk for quitting job will rise. In the United States of America, over 60 percent of physicians would quit their work if they had the means (14).

In African countries, burnout studies are scarce, and most have only been developed in the last decade. The debilitation of health systems due to the human resources crisis has provoked a heavy and complex workload in healthcares and caused substantial workforce burnout. In Malawi, burnout level among maternal health staff at a referral hospital reached 72% emotional exhaustion, 43% depersonalization and 74% low level of personal accomplishment (8).

The state of physician well-being is important for healthcare organizations whose focus has been productivity. However, physicians' stressors had been increased such as time-constrained patient care, lack of resources, decline in compensation and erosion of professional autonomy (15). Most physicians tend to live their lives out of balance (16). A decline in physician satisfaction leads to decrease in quality of the patient care provided and introduces medical errors. This finally results in adverse effects in physician-patient relationships (15).

Work place behaviors such as burnout and stress at work are well researched in developed countries but they are not clearly researched in developing countries particularly in Africa (17–19). As far as the researchers investigated, there is no similar study conducted in Ethiopia on burnout level and its associated factors among physicians. In addition, the number of Ethiopian physicians is not comparable with patient volume so that the physicians in the work become over stressed. It was evidenced that the number of physicians in Ethiopia was estimated to be 1 544. This implies a physician to population ratio of 1:42,706 in Ethiopia and 1:74,161 in Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Regional State (SNNPRS), but the World Health Organization (WHO) minimum standard was 1:10,000 (20). Therefore, this study was designed to address the problems by assessing the burnout level and its associated factors among physicians in public hospitals of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples' Regional State (SNNPRS).

Materials and Methods

Study setting: A cross-sectional study was carried out from March 13 to April 11, 2017 in all primary, general and specialized public hospitals of SNNPRS. Administratively, the Region is divided into 14 zones, 1 city administration and 4 special districts. According to Central Statistical Agency (CSA) 2007 census, the regional total population was 1,492,9548 (male 49.7% and female 50.3%)(21). Currently, there are 40 (8 general and 32 primary) hospitals reporting to the health bureau of the region, and 6 specialized/teaching hospitals are available in the region.

Data collection: Prior to data collection, appropriate data collection tool was adapted from the English version of Maslach's Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). It comprised of 22 items regrouped into 3 subscales: emotional exhaustion (nine items), depersonalization (five items) and personal accomplishment (eight items). Each item was answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “never” (0) to “daily” (6) (6). Questions related to socio-demographic characteristics and other variables were also included in the data collection tool including age, sex, marital status, educational level, number of children, working area, years of experience, duty hours, recognition from hospital manager, professional training, smoking, khat chewing, sleeping hours, satisfaction with monthly salary, physical exercise, working hours, monthly salary, conflict with colleagues and intention to leave work within next six months. This tool was pre-tested on 27(5%) physicians in Jimma University Medical Center and Shenen Gibe General Hospital, located in Oromia Regional State, and its findings were used to modify the tool accordingly.

All 537 physicians who worked in public hospitals of SNNPR for more than six months were included in the study. The data collection was facilitated by fifteen trained diploma nurses.These facilitators were responsible for the distribution and collection of the self-administered questionnaire. As data collection was completed, a reliability test was carried out to check whether the items used to measure burnout were internally consistent. The test revealed that the three dimensions (EE, DP and PA) have Cronbach's alpha results of 0.726,0.719 and 0.702, respectively.

Study variables and measurement: The outcome variable of this study was burnout level; measured in terms of three dimensions including EE, DP and PA. Emotional exhaustion (EE) dimension score was measured by nine items. Scores ≤13, 14–23 and ≥24 represent a low degree of burnout; an average degree of burnout, and a high degree of burnout respectively. Scores of ≤ 2, 3–8, and ≥ 9 in DP dimension represent, low, average, and high degrees of burnout respectively. Personal accomplishment (PA) scores of ≥ 43, 36–42, and ≤ 35 represent low, average, and high degrees of burnout respectively (6).

On the other hand, the independent variables were classified into socio-demographic characteristics which include age, sex, marital status, educational level, number of children and monthly salary. Work-related characteristics comprise of area of service delivery unit, hospital type, duty hours, years of work experience, training, recognition, support from family and organization, intention to leave work within the next 6 months, sleeping hours and working hours. In addition, personal risk behaviors include conflict with colleagues, smoking, drinking alcohol and khat-chewing.

Data processing and analysis: Data were checked for completeness and consistency. Subsequently, they were compiled, cleaned, coded and entered into Epi Data version 3.1 software. Finally it was exported to SPSS version 21 for analysis. Burnout among physicians working in public hospitals of southern Ethiopia was measured in terms of three dimensions. Bivariate analysis was conducted to identify candidate variables for final models. Variables with P-value < 0.25 were included into multiple linear regression analysis. Multiple linear regression analysis was done through enter method to identify the most significant predictors of burnout for each dimension separately. The assumptions of multiple linear regressions (linearity, normality, and constant variance) were checked. The model fitness was checked for all the three models and the adjusted R2 values were 0.191, 0.218 and 0.099 for EE, DP and PA dimensions. Significant independent predictors were declared at P-value less than 0.05, and unstandardized β was used for interpretation.

Ethics approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jimma University, Institute of Health. Moreover, a formal written letter to each hospital was obtained from SNNPR health bureau. Each participant was informed about the aim and potential benefit of the study, and signed informed consent was assured. The data were collected and analyzed anonymously.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics: Five hundred thirty-seven copies of the questionnaire were dispatched for data collection, and 491 were returned with complete responses. The majority of the physicians, 348(70.9%), were males; their mean age was 29.22 ± 4.13 years. They earned 9,514.35 (3,558.34) ETB on average monthly. Four hundred twenty five (86.6%) of the physicians were general practitioners. In relation to marital status, 332(67.6%) were not married. On average, the participants had nearly two years work experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of physicians in public hospitals of SNNPRS, Ethiopia, 2017

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) | |

| Sex | Male | 348 | 70.9 | |

| Female | 143 | 29.1 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 332 | 67.6 | |

| Married | 151 | 30.8 | ||

| Divorced | 6 | 1.2 | ||

| Widowed | 2 | 0.4 | ||

| Number of children | None | 380 | 77.4 | |

| One | 62 | 12.6 | ||

| Two | 30 | 6.1 | ||

| Three | 17 | 3.5 | ||

| Four | 2 | 0.4 | ||

| Educational level | General practitioner | 425 | 86.6 | |

| Specialist | 52 | 10.6 | ||

| Resident | 14 | 2.9 | ||

| Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

| Age in years | 24 | 50 | 29.22 | 4.13 |

| Monthly salary | 5583 | 30000 | 9514.35 | 3558.34 |

| Work experience | 1 | 7 | 1.92 | 1.36 |

Work and personal characteristics: Among those included in this study, 150(30.5%) were employees of primary hospitals; 126(25.7%) were from general hospitals and 215 (43.8%) were from specialized/teaching hospitals. The highest proportion of physicians, 142 (28.9%), were working in medical wards and 108 (22%) in pediatrics, whereas the rest of the respondents were from emergency care units, surgical wards, intensive care units, gynecological wards, ophthalmology and other units. One hundred thirty six (27.7%) of the respondents had the habit of doing physical exercise. On the other hand, 34.2% physicians had plan to leave their work in the future. Regarding professional training and recognition, 55% of the respondents did not get professional training, and 90.2% of them did not receive recognition from hospital managers. Respondents also reported that about 58.7% of them do not have any support from their families and organizations.

It was observed that the mean for professional work experience in the hospital was 1.92 years; sleeping hours in normal working day was 6.22 hours; patients observed per week were 1001; professional worker in the ward was 5.45 while average working hours per week was 53.5 hours. Among the physicians included in this study 48.7% of them have experienced conflict with their colleagues. Moreover, 6.3%,19.1% and 52.5% of the respondents had a habit of smoking cigarrete, chewing khat and drinking alcohols, respectively.

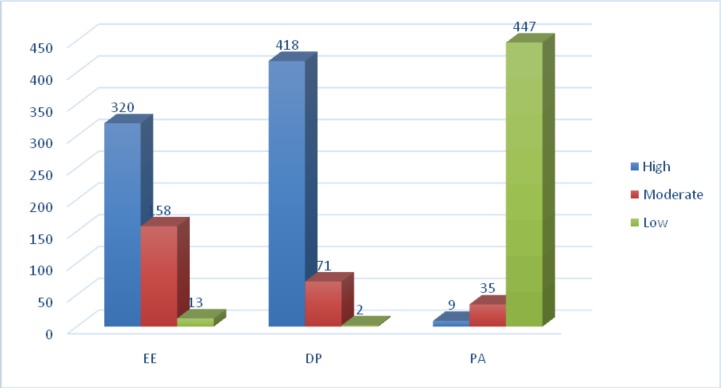

Burnout Level of Physicians: The study revealed that there is a high burnout among physicians working in public hospitals of SNNPR. The mean burnout scores of EE, DP and PA were found 27.2 ± 8, 12.93 ± 5.28 and 25.06 ± 6.56. Among the respondents about 320(65.2%) of them scored high degree of Emotional Exhaustion, 418(85.1%) of them showed high degree of depersonalization and 447(91%) of them experienced low level of personal accomplishment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency and percentage of the three dimensions of burnout among physicians currently working in public hospitals of SNNPRS, Ethiopia, 2017

Note: High level of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization indicates high level of burnout. On the contrary low level of personal accomplishment indicates high level of burnout.

Factors associated with burnout

Factors associated with emotional exhaustion: The result from multiple linear regression indicated that receiving recognition from hospital managers (β: −0.047, 95% CI: −0.091, −0.004), monthly salary (β: −0.012, 95% CI: −0.016, −0.007) and age (β: −0.007, 95% CI: −0.011, −0.003) were negatively associated with emotional exhaustion score. Whereas the number of patients observed per week (β: 0.001, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.003) was positively associated with emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in public hospitals of southern nations, nationalities and peoples' regional state, Ethiopia, 2017

| Variables | Unstandardized βCoefficients |

P-value | [95% CI] | |

| Age in years | −0.007 | 0.001* | −0.011 | −0.003 |

| Monthly salary | −0.012 | 0.000* | −0.016 | −0.007 |

| Number of patients observed per week | 0.001 | 0.000* | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Having any support from family and organization | ||||

| Yes | 0.015 | 0.259 | −0.011 | 0.040 |

| No (reference) | ||||

| Average working hours per week | 0.001 | 0.152 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| Sleeping hours in working day | 0.001 | 0.886 | −0.010 | 0.011 |

| Getting professional training | ||||

| Yes | −0.021 | 0.107 | −0.046 | 0.005 |

| No (reference) | ||||

| Receive recognition from hospital managers | ||||

| Yes | −0.047 | 0.034* | −0.091 | −0.004 |

| No (reference) |

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

Factors associated with depersonalization: The multiple linear regression result indicated that depersonalization was affected by various individual and organizational factors. Age (β: −0.011, 95% CI: −0.015, −0.006), working in primary hospital (β: −0.068, 95% CI: −0.102, −0.033), having any support from family and organization (β: −0.074, 95% CI: −0.104, −0.044), monthly salary (β: −0.014, 95% CI: −0.019, −0.008) and getting professional training (β: −0.032, 95% CI: −0.062, −0.003) were found negatively associated with the dimension (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with depersonalization in public hospitals of southern nations, nationalities and peoples' regional state, Ethiopia, 2017

| Variables | Unstandardized βCoefficients |

P-value | [95% CI] | |

| Age in years | −0.011 | 0.000* | −0.015 | −0.006 |

| Monthly salary | −0.014 | 0.000* | −0.019 | −0.008 |

| Number of patients observed per week | 0.000 | 0.171 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Having support from family and organization | ||||

| Yes | −0.074 | 0.000* | −0.104 | −0.044 |

| No (reference) | ||||

| Working in primary hospital | −0.068 | 0.000* | −0.102 | −0.033 |

| Working in general hospital | −0.020 | 0.265 | −0.056 | 0.015 |

| Working in tertiary (reference) | ||||

| Getting professional training | ||||

| Yes | −0.032 | 0.032* | −0.062 | −0.003 |

| No (reference) | ||||

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

Factors associated with personal accomplishment: Working in primary hospital (β: −0.077, 95% CI: −0.106, −0.049) was negatively associated with personal accomplishment score. In contrast, monthly salary (β: 0.004, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.007) was positively associated with personal accomplishment score (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with personal accomplishment in public hospitals of southern nations, nationalities and peoples' regional state, Ethiopia, 2017

| Variables | Unstandardized βCoefficients |

P-value | [95% CI] | |

| Monthly salary | 0.004 | 0.030* | 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Working in primary hospital | −0.077 | 0.000* | −0.106 | −0.049 |

| Working in general hospital | −0.069 | 0.155 | −0.098 | 0.039 |

| Working in tertiary (reference) having support from family and organization |

||||

| Yes | 0.015 | 0.214 | −0.009 | 0.040 |

| No (reference) | ||||

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

Discussion

This study examined burnout level and factors triggering it among physicians working in southern Ethiopia. Burnout is determined by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment subscale values. The burnout level was assessed using the Maslach's Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBIHSS) and linear regression identified the associated factors. The finding showed that generally, there is a high burnout in all the three dimensions of burnout among physicians. Specifically, 65.2% were in high emotional exhaustion, 85.1% in high depersonalization and 91% in low personal accomplishment that comprised high burnout level.

Although there is scarce information on burnout among physicians in sub-Saharan Africa and Ethiopia, there are a lot of studies done in other settings. Similar studies conducted in Yemen (22), Malaysia (23), Brazil (24) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (25) showed different results from this study. In all the three dimensions of burnout, the proportion of physicians in the highest group that means in high EE, DP and low PA is by far lower than this study. Some similarities with this study are seen in the Egyptian (26) and Hungarian (27) studies in the low PA dimension of burnout. The proportion of physicians in these studies were 99.2% and 100%, respectively. Similar to the above studies in other dimensions of burnout, the results are lower in these two studies too.

Possibly, these differences occurred because of variation in workplace culture, the volume of patients treated by a single physician, the nature of the health system, the responsibility and role expected from a physician and poor employment condition in Ethiopia.

The multiple linear regression models revealed that the main predictors of burnout in all the three dimensions were age of the physician, monthly salary, hospital type, receiving recognition from hospital managers, professional training and having support from family and organization both positively and negatively.

In this study, the average number of patients examined per week was positively associated with emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout level. Similar studies done in a Provinces of Eastern Anatolia and Turkey support this finding (28,29). Increase in physicians' age results in reduction in EE and DP dimensions of burnout. On the other hand, this variable has a positive effect on PA score of the Turkey's study. Other dimensions are not affected by age in this study (30).

In this study, being employed in primary hospitals decreases DP score by 0.068. On the contrary, a study done in Shangai revealed that working in primary hospital increases DP score by 0.17 (31). The differences in the studies occurred because the patient flow and work load in primary hospitals of Ethiopia are less as compared to the Chinas.

This investigation identified seven variables that significantly affect burnout level dimensions both positively and negatively. Three of them were also common in the above discussed studies. However, monthly salary, recognition from hospital managers, professional training and having any support from family and organization were found different for this study.

Burnout was measured in three dimensions and was found high among physicians currently working in public hospitals of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region, Southern Ethiopia. Receiving recognition from hospital managers, age, working in primary hospital, monthly salary, having support from family and organization, and getting professional training can possibly minimize the level of burnout among physicians in the region. On the contrary, increase in the number of patients observed per week increases burnout.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jimma University for funding this study. We are also grateful to hospital managers, data collectors and supervisors of the study and others who assisted us during data collection.

References

- 1.Rennie J, DiChristina M, Fischetti M. Scientific American MIND: The Science of Burnout. Scientific American Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaufeli WB, Greenglass ER. Introduction to special issue on burnout and health. Psychol Health [Internet] 2001;16(5):501–510. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405523. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08870440108405523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and Medical Errors Among American Surgeons. Ann Surg [Internet] 2010;251(6):995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00000658-201006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tennant C. Work-related stress and depressive disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51(5):697–704. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter M. The Maslach Burnout Inventory: Manual. Maslach Burn Invent [Internet] 1996 Jan;:191–218. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277816643. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Wollner N, Meyers PA, Lindsley KL, Ghavimi F, et al. Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor: Prolonged progression-free survival with aggressive multimodality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(5):1526–1531. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorsen VC, Tharp ALT, Meguid T. High rates of burnout among maternal health staff at a referral hospital in Malawi: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs [Internet] 2011;10(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-9. Available from: http://bmcnurs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6955-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okerlund VW, Parsons RJ. Factors Affecting Recruitment of Physical Therapy Personnel in Utah. J Am Phys Ther. 1994;74(2):177–184. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogresta J, Rusac S, Zorec L. Relation between burnout syndrome and job satisfaction among mental health workers. Croat Med J. 2008;49(3):364–374. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeborn DK. Satisfaction, commitment, and psychological well-being among HMO physicians. West J Med. 2001 Jan;174:13–18. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visser MRM, Smets EMA, Oort FJ, Haes HCJM de. Stress, satisfaction and burnout among Dutch medical specialists. Can Med Assoc. 2003;168(3):271–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thommasen H V, Lavanchy M, Connelly I, Berkowitz J, Grzybowski S. Mental health, job satisfaction, and intention to relocate: Opinions of physicians in rural British Columbia. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47(APR):737–744. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins Merritt. A Survey of America's Physicians: Practice Patterns and Perspectives. Physicians Found. 2012:1–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, Homer L. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: Assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544–1552. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0363-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers MF. The well-being of physician relationships. West J Med. 2001;174(January):30–33. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr C, Pudelko M. Convergence of Management Practices in Strategy, Finance and HRM between the USA, Japan and Germany. Int J Cross Cult Manag. 2006;6(1):75–100. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haque A, Aslam MS. Far East Journal of Psychology and Business Vol 4 No 2 August 2011. Far East J Psychol Bus. 2011;4(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey. Anxiety, Stress Coping. 2002;15(3):245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Monetary Fund, author. IMF Country Report No. 13/308. IMF Country Report No. 13/308. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Central Statistical Authority, author. 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Administrative Report [Internet] 2012. Available from: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/censuskb20/Attachment489.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdo S, Ubai A-R, Ampal KGR. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Burnout among Doctors in Yemen. J Occup Health. 2010;52:58–65. doi: 10.1539/joh.o8030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoo EJ, D M, Aldubai S, Ganasegeran K, D M. Emotional exhaustion is associated with work related stressors: a crosssectional multicenter study in Malaysian public hospitals. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(3):212–218. doi: 10.5546/aap.2017.eng.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanatta AB, Lucca SR De. Prevalence of Burnout syndrome in health professionals of an onco-hematological pediatric hospital. J Sch Nurs. 2013;49(2):251–258. doi: 10.1590/S0080-623420150000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pranjić N. Burnout and Predictors for Burnout among physicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina- survey and study. Acta Med Acad. 2006;35:66–76. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdo SAM, El-Sallamy RM, El-Sherbiny AAM, Kabbash IA. Burnout among physicians and nursing staff working in the emergency hospital of Tanta University, Egypt. East Mediterr Heal J. 2015;21(12):906–915. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.12.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adám S, Torzsa P, Gyorffy Z, Vörös K, Kalabay L. Frequent high-level burnout among general practitioners and residents. Orv Hetil. 2009;150(7):317–323. doi: 10.1556/OH.2009.28544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taycan O, Taycan SE, Çelik C. The Impact of Compulsory Health Service on Physicians and Burnout in a Province in Eastern Anatolia. Turkish J Psychiatry. 2012:1–5. (Beck 2001) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toker İ, Ayrık C, Bozkurt S, Tür FÇ, Başterzi AD, Hacar S, et al. Factors Affecting Burnout and Job Satisfaction in Turkish Emergency Medicine Residents. Emerg Med - Open J [Internet] 2015;1(3):64–71. Available from: http://openventio.org/Volume1_Issue3/Factors_Affecting_Burnout_and_Job_Satisfaction_in_Turkish_Emergency_Medicine_Residents_EMOJ_1_11.pdf%5C http://openventio.org/Volume1-Issue3/Factors-Affecting-Burnout-and-Job-Satisfaction-in-Turkish-Emergency-Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozyurt A, Hayran O, Sur H. Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians. Adv Access Publ. 2006;99:161–169. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, Xie Z, Dai J, Zhang L, Huang Y, Chen B. Physician burnout and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study in Shanghai. J Occup Health. 2014;56(1):73–83. doi: 10.1539/joh.13-0108-oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]