Abstract

Objective:

This study sought to evaluate whether a contact-based workplace education program was more effective than standard mental health literacy training in promoting early intervention and support for healthcare employees with mental health issues.

Method:

A parallel-group, randomised trial was conducted with employees in 2 multi-site Ontario hospitals with the evaluators blinded to the groups. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 group-based education programs: Beyond Silence (comprising 6 in-person, 2-h sessions plus 5 online sessions co-led by employees who personally experienced mental health issues) or Mental Health First Aid (a standardised 2-day training program led by a trained facilitator). Participants completed baseline, post-group, and 3-mo follow-up surveys to explore perceived changes in mental health knowledge, stigmatized beliefs, and help-seeking/help-outreach behaviours. An intent-to-treat analysis was completed with 192 participants. Differences were assessed using multi-level mixed models accounting for site, group, and repeated measurement.

Results:

Neither program led to significant increases in help-seeking or help-outreach behaviours. Both programs increased mental health literacy, improved attitudes towards seeking treatment, and decreased stigmatized beliefs, with sustained changes in stigmatized beliefs more prominent in the Beyond Silence group.

Conclusion:

Beyond Silence, a new contact-based education program customised for healthcare workers was not superior to standard mental health literacy training in improving mental health help-seeking or help-outreach behaviours in the workplace. The only difference was a reduction in stigmatized beliefs over time. Additional research is needed to explore the factors that lead to behaviour change.

Keywords: health personnel, clinical trial, evaluation studies, early intervention (education), stigma, training programs, mental health, workplace, professional education, employment

Abstract

Objectif :

Évaluer si un programme d’éducation par contact en milieu de travail a été plus efficace que la formation standard de littératie en santé mentale pour promouvoir l’intervention précoce et le soutien des employés de la santé ayant des problèmes de santé mentale.

Méthode :

Un essai randomisé, à l’insu de l’évaluateur et à groupes parallèles a été mené auprès des employés de deux hôpitaux multicentriques en Ontario. Les participants ont été affectés au hasard à l’un de 2 programmes d’éducation en groupe: Au-delà du silence (six séances de 2 heures en personne plus 5 séances en ligne menées conjointement par des employés ayant personnellement des problèmes de santé mentale), ou Premiers soins de santé mentale (un programme de formation normalisé en 2 jours mené par un animateur formé). Les participants ont répondu à des sondages au départ, post-groupe et au suivi de 3 mois pour explorer les changements perçus des connaissances en santé mentale, des croyances stigmatisées et des comportements de recherche et d’offre d’aide. Une analyse d’intention de traitement a été effectuée auprès de 192 participants. Les différences ont été évaluées à l’aide de modèles mixtes à plusieurs niveaux représentant le site, le groupe et les mesures répétées.

Résultats :

Aucun programme n’a entraîné d’augmentation significative de la recherche d’aide ou de l’offre d’aide. Les deux programmes ont enrichi la littératie en santé mentale, amélioré les attitudes à l’égard de la recherche de traitement, et réduit les croyances stigmatisées, des changements soutenus des croyances stigmatisées étant plus apparents dans le groupe Au-delà du silence.

Conclusion :

Au-delà du silence, un nouveau programme d’éducation par contact adapté pour les travailleurs de la santé, n’était pas supérieur à la formation standard de littératie en santé mentale pour améliorer les comportements de recherche d’aide ou d’offre d’aide en santé mentale en milieu de travail. La seule différence était la réduction des croyances stigmatisées avec le temps. Il faut plus de recherche pour explorer les facteurs qui mènent à un changement de comportement.

Background/Rationale

Mental health in the workplace is a growing concern for many employers, with significant financial and human costs associated with mental health problems. In particular, the health and social service sector depends on workers with good psychological health to provide quality care to patients/clients. Unfortunately, many healthcare workers experience pressures that can detract from their psychological health and well-being. The emotionally demanding nature of healthcare work, heavy workloads, as well as limited time and resources can take an emotional toll, and lead to higher rates of absenteeism and presenteeism when compared to workers in other sectors.1 Furthermore, the stigma associated with mental health problems can lead to delays between the onset of symptoms and receiving treatment.2 Issues may be ignored or overlooked due to a lack of understanding regarding mental health disorders and their treatment, as well as the stigma associated with seeking help.3

Education in the form of mental health literacy training can help to build the knowledge and beliefs required to recognize, manage, and prevent employee mental health problems.4 A recent review study noted the growing number of educational resources designed for the workplace, from online webinars and modules to in-person training sessions about psychological health and safety.5 One of the most commonly cited and well-known mental health education programs is Mental Health First Aid (MHFA); it is a standardised, module-based program designed to teach participants how to recognize the early warning signs of common mental illnesses, how to provide initial help to someone in a mental health crisis, and how to support people who are developing mental health problems.6 The program was developed to educate the general public and has been implemented in a range of settings around the world.7 There is a growing evidence base supporting its effectiveness in increasing mental health literacy.8

Although MHFA is an established, evidence-based program, some have recognised that the program may need to be tailored to specific target groups, such as youth, First Nations communities and even the workplace.9–12 Healthcare workers, in particular, may have unique needs in terms of education and training. Many healthcare workers, for example, develop knowledge about mental disorders through their professional training, and deal with patient mental health issues on a day-to-day basis. As such, it is expected that their mental health literacy could be higher than employees in other organizations. Ironically, it has been noted that the stigma associated with mental illness can be higher among healthcare workers, and that a medical perspective is linked to a view of mental illness as fixed and chronic.13 The focus of MHFA on teaching the signs and symptoms of various disorders may reinforce a medical viewpoint that could be problematic in a workplace context where employees should not be diagnosing or treating their colleagues. It has been argued that mental health literacy in the the workplace should focus less on the diagnosis and more on work performance issues, and policies, procedures, and supports that are relevant to the context of employment.14 This speaks to the need for customised training that is relevant to the unique context of healthcare.

The Beyond Silence program was developed by the primary author to address the unique educational and support needs of healthcare workers. Curriculum design was informed by the findings of several qualitative studies with healthcare workers,3,15 a review of other workplace programs, and best-practice principles of contact-based education and adult education. It includes examples and resources that are customised for healthcare organizations. The contact-based education approach was devised on the premise that positive, voluntary contact over time with a person who has a stigmatized condition is the most effective way to reduce stigma and discrimination.16 As such, the programs are co-led by ‘peer educators’: healthcare workers who have personal experience with mental health or addictions issues and are trained to deliver the program.

The purpose of this study was to compare the impact of a customized, contact-based education approach (Beyond Silence) with standard mental health literacy training (MHFA) on the help-seeking/help-outreach behaviours of healthcare employees.

Methods

Design

A multi-centre, parallel-group design was conducted with employees in 2 large Ontario hospitals. Patients were randomized to 1 of 2 intervention groups by blinded evaluators. It was hypothesised that the Beyond Silence program would be more effective that the Mental Health First Aid training in terms of the primary outcome of change in mental health help-seeking/help-outreach behaviours. Secondary hypotheses were that both programs would lead to an increase in mental health literacy, but the Beyond Silence program would be more effective in reducing stigmatized beliefs and improving attitudes towards treatment. Because the Beyond Silence program includes a contact-based educational approach, we hypothesised that it would be superior in terms of reducing stigmatized beliefs and ultimately in increasing help seeking and help outreach behaviour.

Participants

Recruitment in each hospital was achieved through information meetings with organizational leaders and managers, who then shared details with their staff; email communication through advisory team members; hospital newsletters; information booths at health fairs; and posters in public spaces in the hospitals. Inclusion criteria included any full- or part-time employee within the organization who was willing to be randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 interventions, and who agreed to attend the sessions outside of their work hours. A basic understanding of English was also needed to be able to participate.

There were 8 intakes over the course of 1 y (September 2014 to October 2015). In each intake, employees were randomly assigned to one of two 12-h educational interventions (Beyond Silence or Mental Health First Aid). There were 5 intakes in Hospital 1, and 3 in Hospital 2. In each intake, a 1:1 random allocation sequence was generated using the software STATA by an off-site investigator [SP] who was not involved in enrolling or assigning participants to the intervention. This was accomplished by generating a single, random number from a uniform distribution for each participant in each intake. Participant ID numbers were used rather than names to conceal identity. The list of participant ID numbers was then sorted by this random number, with the top and bottom halves of each list assigned to Beyond Silence and MHFA, respectively. The project coordinator informed participants about their group assignment using the allocation sequence and had no discretion to alter it. Randomization occurred in 1 block of 24 (12 in each assignment group); 5 blocks of 26 (13 in each assignment group); 1 block of 30 (15 in each assignment group), and 1 block of 32 (16 in each assignment group). The different numbers in each intake reflect efforts later in the project to over-recruit to compensate for drop-outs.

The target number of participants to enroll in the study was based on a priori sample size calculations that were predicated on assumptions regarding behaviour change outlined in the study protocol.17 The final sample included 192 participants who were randomised to the interventions and had at least one baseline data point for analysis.

Interventions

Both programs included approximately 12 h of group-based education, led by trained leaders, but the content and format were different. Beyond Silence is a newly developed program, based on principles of contact-based education, designed to promote early intervention and support for workers with mental health issues. Details regarding program development and principles of implementation have been published previously.17 Each program consisted of six 2-h, in-person sessions, alternating with 5 online sessions. The in-person sessions were held every other week for a period of 3 mo, and were designed to build on each other, starting with ‘why mental health matters’, then moving to skill building in identifying and reaching out for help, and reviewing potential resources. The online sessions were designed to complement and extend the in-person sessions, where participants could explore and comment on web-based resources. All sessions were co-led by ‘peer educators’: healthcare workers who had personal experience with mental health or addictions issues and who were trained to deliver the program. A fidelity rating scale was developed to capture 17 key structural and content elements of the program delivery. The fidelity ratings were completed by an external evaluator during session 4 or 5, and all demonstrated over 80% compliance.

The Mental Health First Aid program was led by a certified MHFA trainer who was also an employee of the organization (but did not share personal experiences with mental health issues). The MHFA curriculum is a standardized, module-based program designed to teach participants how to recognize the early warning signs of common mental illnesses, how to provide initial help to someone in a mental health crisis, and how to support people who are developing mental health problems.6 The 2 full-day sessions were scheduled 1 wk apart and participants were required to attend both sessions. Fidelity to the program principles were monitored by Mental Health First Aid Canada, since this is part of their requirement for implementation.

Data Collection

Online surveys were completed by participants at 3-mo intervals: at baseline, immediately following program completion (at 3 mo), and 3 mo following program completion (at 6-mo). There were 6 sections in each survey: 1) demographic data (gender, age, job tenure, position); 2) personal mental health experience (whether self or family member had experienced a disorder); 3) mental health literacy (subjective rating of literacy based on a standardised tool with 4 workplace vignettes18); 4) stigma towards co-workers with mental illness (based on the 15-item Opening Minds Scale for Health Care providers19,20); 5) help-seeking behaviour (including the standardised Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale21); and 6) help-outreach behaviour (total number of behaviours based on a pre-identified list). In addition, the post-group and follow-up surveys included open-ended questions asking for feedback on the programs. For additional details on each section of the survey, see the study protocol.17

Data Analysis

The analysis plan was designed to address the primary research questions: Is Beyond Silence more effective than standard MHFA in increasing the help-seeking/outreach behaviours of workers in a healthcare setting? We also sought to evaluate whether enhanced performance of Beyond Silence was mediated by greater changes in literacy, attitudes towards others, or attitudes towards seeking professional treatment. Outcomes of both interventions were described and compared. We first used descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation and graphical techniques to characterize the study groups and evaluate statistical assumptions. Next, we used a multi-level mixed model to compare the groups. In this model, the intake groups were nested within the 2 hospital sites, people were nested within intake groups, and repeated measures were nested within people. To assess differences due to treatment, we examined treatment by time interactions, using the statistical significance of the interaction term to test whether the effect of the 2 treatments differed at any time. We had initially proposed using a Poisson model to represent counts of help-providing behaviours; however, the counts had a bimodal distribution. Many respondents had no behaviours, presumably because they did not encounter anyone who needed help, and among the remainder there was a bell-shaped distribution. Therefore, we adopted a linear regression approach to the analysis, modeling the mean number of behaviours among those who had an opportunity to offer help. A similar approach was taken in the analysis of help-seeking behaviour, restricting this analysis to the subset reporting a mental health experience that might have motivated help seeking. The remaining variables: changes in stigma, attitudes toward help-seeking, and knowledge were analyzed with multi-level models, evaluating whether mean scores on the relevant instruments depended on treatment group, using group-by-time interaction terms. The mixed modeling approach allowed inclusion of respondents with missing data at a particular time point and may reduce bias due to missing data. Imputation was therefore not used in the analysis.

Results

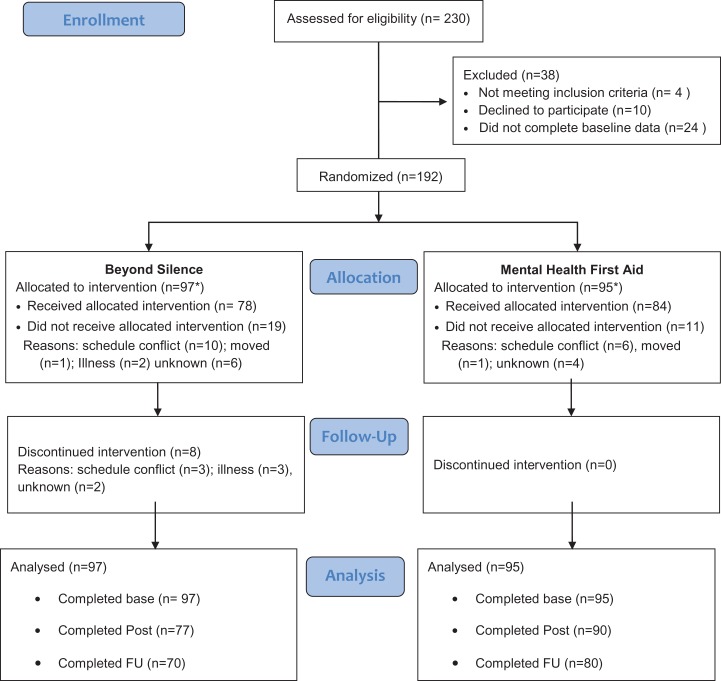

A CONSORT diagram describing the sample is presented in Figure 1. A total of 192 employees were randomised. Of these, 97 were assigned to the Beyond Silence intervention and 95 to the MHFA group (one participant was mistakenly assigned to the Beyond Silence program). Most participants were female (88.5%), full-time employees (74.5%), and engaged in clinical roles (59.4%).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Demographic features of the sample were those expected of employees in health care settings. As expected due to the randomization, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups (see Table 1). At the 3-mo assessment, data collection was complete for 167 respondents. At the 6-mo follow-up, data was successfully collected from 150 respondents. Those with incomplete data did not differ from those with complete data on any of the variables listed in Table 1 (all P > 0.28).

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics.

| Total Sample | Beyond Silence | MHFA | P value Fisher’s Exacta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 1 | 130 | 67.7% | 65 | 67.0% | 65 | 68.4% | – |

| 2 | 62 | 32.3% | 32 | 33.0% | 30 | 31.6% | ||

| Sex | Female | 170 | 88.5% | 85 | 87.6% | 85 | 89.5% | 0.822 |

| Male | 22 | 11.5% | 12 | 12.4% | 10 | 10.5% | ||

| Age (y) | 18 to 29 | 25 | 13.0% | 14 | 14.4% | 11 | 11.6% | 0.242 |

| 30 to 39 | 39 | 20.3% | 18 | 18.6% | 21 | 22.1% | ||

| 40 to 49 | 54 | 28.1% | 33 | 34.0% | 21 | 22.1% | ||

| 50 to 59 | 56 | 29.2% | 26 | 26.8% | 30 | 31.6% | ||

| 60 to 69 | 18 | 9.4% | 6 | 6.2% | 12 | 12.6% | ||

| Role | Clinical service | 114 | 59.4% | 62 | 63.9% | 52 | 54.7% | 0.302 |

| Support | 38 | 19.8% | 19 | 19.6% | 19 | 20.0% | ||

| Management | 40 | 20.8% | 16 | 16.5% | 24 | 25.3% | ||

| Employment Status | Full time | 143 | 74.5% | 74 | 76.3% | 69 | 72.6% | 0.369 |

| Part time | 40 | 20.8% | 17 | 17.5% | 23 | 24.2% | ||

| Occasional | 9 | 4.7% | 6 | 6.2% | 3 | 3.2% | ||

| Total | 192 | 100.0% | 97 | 50.5% | 95 | 49.5% | ||

MHFA, mental health first aid.

aTwo-sided test, comparing Beyond Silence to MHFA.

The primary analysis examined behaviours related to reaching out to help others at work with mental heath issues (e.g., listen, recommend professional help, offer assistance with job duties). As noted above, this behaviour analysis was restricted to those respondents who reported contact with a person who appeared to be in need of help. At baseline, 113/192 (59%) reported contact, whereas the numbers at the second and third assessment were 113/167 (68%) and 91/150 (61%), respectively. In the multi-level mixed model, time by arm interactions in the help-outreach behaviours were not significant (Likelihood ratio Chi-square = 0.34, d.f. = 2, P = 0.85). With removal of the interaction terms, there was no significant change from baseline either at the 3-mo- (beta = 0.29, z = 1.38, P = 0.169) or 6-mo (beta = 0.32, z=1.48, P = 0.138) follow-up. Similar results were found when the helping behaviours were analysed as a dichotomous outcome, when the analysis was restricted to completers, or when the data were analysed at one site only. The mean number of helping behaviours ranged from 3.92 (baseline in the MHFA) to 4.46 (6-mo follow-up in the Beyond Silence group). In both treatment arms, at all 3 time points, helping behaviours were offered about 80% of the time when a person needing help was encountered.

Similarly, the investigation of help-seeking behaviours was limited to those reporting a mental health experience that might have led to help seeking. There were 99 respondents reporting a mental health experience at baseline, 101 at 3 mo (post-group) and 89 at 6 mo. At visits in which a mental health experience was reported, 218/289 or 75.4% were associated with a report of help seeking. In an analysis similar to that reported above, there was no evidence of a treatment arm by time interaction either at 3 mo (beta = 0.018, z = 0.21, P = 0.834) or 6 mo (beta = −0.043, z = −0.49, P = 0.624). Similarly, there were no interactions for treatment arm by time on attitudes towards treatment seeking; however, with removal of the interaction terms, improvements in attitudes towards help seeking were evident at 3 mo (beta = 1.71, z = 7.2, P < 0.001) and 6 mo (beta = 1.67, z = 6.77, P < 0.001), with no difference between the 2 interventions (beta = 0.464, z = 1.09, P = 0.274).

In the stigma analysis, no interactions for treatment arm by time were observed at 3 mo (beta = −0.21, z = −0.22, P = 0.83); although, a possible trend for superior outcomes for Beyond Silence was seen at 6 mo (beta = 1.72, z = 1.7, P = 0.089). To explore whether the anti-stigma effects of Beyond Silence might be more persistent than those of MHFA, a model describing changes from 3 to 6 mo was fit, revealing a significant treatment by time interaction (beta = 1.89, z = 2.09, P = 0.037).

In the analysis of knowledge outcomes, there was again no evidence of a treatment by arm interaction either at the 3 mo (beta = 1.68, z = 1.08, P = 0.281) or 6 mo (beta = 1.94, z = 1.2, P = 0.231) follow-up. Upon removal of the interaction terms, increases in knowledge were significant both at 3 mo (beta = 13.99, z = 17.88, p < 0.001) and 6 mo (beta = 13.63, z = 16.78, P < 0.001) but there was no difference between the treatment arms (beta = −0.43, z = −0.34, P = 0.736).

Discussion

The study findings did not reveal any significant changes in behaviour related to either help-seeking or help-outreach. This finding was disappointing because behaviour change was one of the primary goals of the educational programs. There are several potential reasons for what appears to be a limited transfer between changes in knowledge and attitudes to changes in behaviour. One is that the tool that was used to track behaviours may not be the optimal way of capturing meaningful behaviour change. First of all, the pre-set list of 10 help-seeking and 10 help-outreach behaviours only tracks whether an additional behaviour was added to (or removed from) the individual’s repertoire of options. It does not indicate whether specific behaviours were more frequent or whether the behaviour was completed with more skill and/or had more of an impact. For example, the tool adopted in this study would only be able to note whether a participant added an outreach behaviour, such as ‘recommending the Employee Assistance Program’, not whether they did this with more people or were more effective in making a recommendation. It would be helpful to add a measure of quality rather than just quantity, and to gather more details about when and how these actions unfolded in the context of the workplace. The baseline number of behaviours demonstrated by participants was already fairly high (mean of 4+ behaviours), which may reflect that participants in this study were already engaged in helping behaviours. It was expected that there would be a normal distribution of scores from low to high, when in fact there was more of a bi-modal distribution, with a percentage of workers who did not enage in any behaviours, and others who engaged in 4 or 5 different behaviours. A more detailed analysis may be needed to explore who is more (or less) likely to provide or seek help from others, and how this changes (or doesn’t change) over time. More than 3 mo of post-program follow-up may be needed to track the impact on workplace practice.

The study findings did illustrate that both the MHFA and the Beyond Silence programs were effective in enhancing perceived knowledge about mental health issues, reducing stigmatized beliefs, and improving attitudes toward seeking help. The positive impact of MHFA on these outcomes has been reported in many studies in the literature, including some workplace-based studies.12,6 Although the Beyond Silence program was not superior to MHFA training, this is the first study to illustrate similar outcomes in 2 different workplace mental heath education programs. Furthermore, the findings suggest a possible added value of Beyond Silence, a contact-based, educational program, in sustaining reductions in stigmatized beliefs. This is an important finding since stigma is one of the key barriers preventing healthcare workers from seeking mental health treatment for themselves, or reaching out to provide help to others.3 Because healthcare workers may already have a strong baseline knowledge about mental illness, a sustained change in attitudes or beliefs may be the key to overcoming barriers to early intervention and support. Our study findings were consistent with reports in the literature regarding the immediate impact of mental health literacy training (including MHFA) on stigmatized beliefs; however, it is critical to explore strategies that will sustain these changes over time. A longer-term follow-up is needed to investigate such changes over time. It is also important to note that the sustained impact of the contact-based approach in the Beyond Silence program was further supported by qualitative data regarding program implementation.22

One of the strengths of this study was that the randomization process reduced the risk of bias in comparing the outcomes of the 2 programs. In addition, the follow-up period facilitated our understanding of whether changes were sustained over time. A limitation of the study is that it was conducted with hospital employees in one geographic region of Ontario. Participants in the study were volunteers, so they may be more open and receptive to the educational programs. Further research is needed to engage a higher percentage of male employees, non-clinical staff, and individuals who may not be as receptive to the education provided. In addition, research is needed to explore whether the findings are replicated in smaller organizations in rural settings in other jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Neither workplace training program led to a significant change in mental health help-seeking or outreach behaviours. The Beyond Silence program, a contact-based, educational program customised for healthcare employees, did not appear to be superior to Mental Health First Aid training: both programs led to increases in mental health literacy, reduced stigma, and improved attitudes towards help-seeking. Although the Beyond Silence program led to more sustained reductions in stigmatized beliefs, further research is needed to explore which parts of workplace mental health training promote early intervention and support for the mental health of healthcare workers.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Ontario Mental Health Foundation.

ORCID iD: Sandra E. Moll, MSc(OT), PhD  http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1937-0103

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1937-0103

Scott Patten, MD, PhD  http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9871-4041

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9871-4041

References

- 1. Gartner FR, Nieuwenhuijsen K, van Dijk FJ, et al. The impact of common mental disorders on the work functioning of nurses and allied health professionals: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(8):1047–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RC, Frank RG. The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):861–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moll S. The web of silence: a qualitative case study of early intervention and support for healthcare workers with mental ill-health. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. Mental health literacy: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canadian Mental Health Association. Workplace Mental Health in Canada: Findings from a Pan-Canadian Survey. Toronto, ON: Canadian Mental Health Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry. 2002;2:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid: an international programme for early intervention. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hadlaczky G, Hokby S, Mkrtchian A, et al. Mental health first aid is an effective public health intervention for improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(4):467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caza M. Final Report: Evaluation of the Mental Health First Aid Training in First Nations Communities in Alberta. Ottawa, Canada: Mental Health First Aid Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bovopoulos N, Jorm AF, Bond KS, et al. Providing mental health first aid in the workpace: A Dephi consensus study. BMC Psychology. 2016;4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kelly CM, Mithen JM, Fischer JA, et al. Youth mental first aid: a description of the program and an initial evaluation. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid training in a workplace setting: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bourget B, Chenier R. Mental Health Literacy In Canada –Phase 1 Draft Report Mental Health Literacy Project. ON, Canada: Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shain M, Baynton MA. Preventing Workplace Meltdown: An Employer’s Guide To Maintaining A Psychologically Safe Workplace. Toronto, Canada: Carswell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moll S, Eakin J, Franche R-L, et al. When health care workers experience mental ill health: Institutional practices of silence. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(2):167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stuart H, Arboleda-Florez J, Sartorius N. Paradigms Lost: Fighting Stigma and the Lessons Learned. New York, NY: Oxford; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moll S, Patten S, Stuart H, Kirsh B, MacDermid JC. Beyond silence: Protocol for a randomized, parallel-group trial comparing two approaches to workplace mental health education for healthcare employees. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moll S, Zanhour M, Patten S, Stuart H, MacDermid J. Evaluating mental health literacy in the workplace: Development and psychometric properties of a vignette-based tool. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(4):601–611. Epub 2017 Jan 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kassam A, Papish A, Modgill G, Patten S. The development and psychometric properties of a new scale to measure mental illness related stigma by health care providers: the opening minds scale for health care providers (OMS-HC). BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Modgill G, Patten SB, Knaak S, Kassam A, Szeto AC. Opening minds stigma scale for health care providers (oms-hc): examination of psychometric properties and responsiveness. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elhai JD, Schweinle W, Anderson SM. Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159(3):320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moll S, VandenBussche J, Brooks K, et al. Workplace mental health training in healthcare: Key ingredients of implementation. Can J Psychiatry. 2018. [Advanced online publication]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]