Abstract

Background

Clinical depression in children as young as 3 has been validated with prevalence rates similar to the school-age disorder. Homotypic continuity between early and later childhood depression has been observed, with alterations in brain function and structure similar to those reported in depressed adults. These findings highlight the importance of identifying and treating depression as early as developmentally possible, given the relative treatment resistance and small effect sizes for later life treatments. The need for studies of psychotherapies for early childhood depression is also underscored by increases in psychotropic medication prescriptions for young children, representing a public health crisis. To date, there have been no large-scale clinical trials of psychotherapies for early childhood depression.

Methods

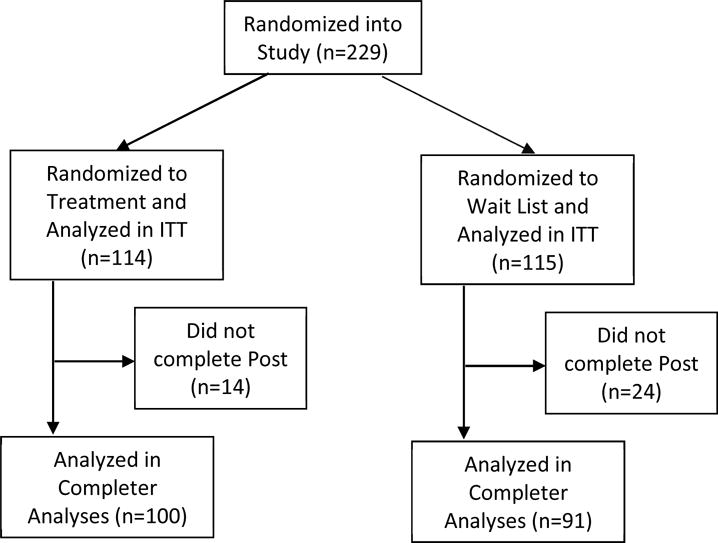

A parent-child psychotherapy, a modified version of the empirically tested Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with a novel “Emotion Development” module (PCIT-ED) was compared to a wait list (WL) condition in a randomized controlled trial of N=229 parent-child dyads.

Results

Young children who received PCIT-ED had lower rates of depression (primary outcome), lower depression severity, and lower impairment compared to those in the WL condition (Cohen’s d > 1.0). Measures of child emotional functioning and parenting stress and depression were significantly improved in the treatment group.

Conclusions

Findings from this RCT of a parent-child psychotherapy for early childhood depression suggest that earlier identification and intervention in this chronic and relapsing disorder represents a key new pathway for more effective treatment. Manualized PCIT-ED, administered by master’s level clinicians, is feasible for delivery in community health settings.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 2 decades, empirical studies have validated clinical depressive disorders in children as young as age 3 (1–5). Early childhood depression has been detected in U.S. and international epidemiological samples at prevalence rates of 1-2%, comparable to school age depression (5–8). Homotypic continuity between early and later childhood depression has been observed in longitudinal studies, establishing developmental continuity of the disorder (9, 10). Alterations in brain function and structure, similar to patterns observed in adolescent and adult depression, have been found in school-age children with a history of early childhood depression followed longitudinally, even when depression had remitted (11–13). Additionally, alterations in functional brain activity and connectivity similar to that found in depressed adults have been reported in acutely depressed preschoolers (14–17). These behavioral and brain findings show that clinical depression can arise in early childhood and has similar phenotypic and biological characteristics to the adult form. Such findings underscore the importance of identifying and treating this disorder at these early developmental stages. However, to date there are no empirically tested treatments for early childhood depression.

The need for the development and testing of early interventions for depression is further emphasized by findings that the school-age form of the disorder has proven to be difficult to effectively treat using available interventions. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in depressed school-age children, a treatment with known efficacy in depressed adolescents, demonstrated only small to moderate effect sizes (0.35 overall) (18). This has led to a call for new models for investigating depressive (and other) disorders using a neuro-developmental approach (19, 20). In this context, the relatively large effect sizes reported in several early childhood interventions for other forms of psychopathology and developmental disability are of interest (21–23). A number of factors, including the powerful influence of the parent-child relationship, as well as greater neuroplasticity of brain in early childhood (24), may serve as unique contributors to the robust treatment effects evident in earlier interventions. Similar to the well-established greater efficacy of early interventions to remediate developmental disorders, these promising findings in other childhood psychiatric disorders raise the possibility that earlier interventions in depressive disorders may provide a window of opportunity for more effective treatment.

The need for studies of early psychotherapeutic interventions for depression is further underscored by sharp increases in the use of psychotropic medications for young children, representing a public health crisis (25–27). Zito et al. (28) reported that 20% of all psychotropic prescriptions for preschoolers were antidepressants, and the use of antidepressants increased significantly with increasing age during the preschool period (ages 3-6). Olfson et al. (29) reported striking increases in the prescription of antipsychotics to preschoolers with depression diagnoses following the black box warning on antidepressants, and declining rates of psychotherapy use in preschoolers. Given the unknown efficacy and questions about the long term safety of these agents in developing young children, these trends strongly point to the need for a safe and effective psychotherapuetic treatment for preschoolers with depressive disorders.

Given these issues, we sought to develop and test a novel psychotherapy for early childhood depression. To do this, we adapted and tested the widely used and proven effective early intervention for disruptive disorders, “Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT),” which has established large and sustained effects (30, 31). Utilizing the basic techniques of PCIT, we added a novel “emotion development” module to address depressive symptoms, dubbed PCIT-ED. Building on promising findings from a pilot study (32), a large scale randomized controlled trial was launched at the Washington University School of Medicine Early Emotional Development Program (WUSM EEDP).

METHODS

Overview

This single blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared PCIT-ED to a wait list control (WL). A WL control comparison condition was justified based on two factors. First, there is no other empirically tested or widely used treatment for early childhood depression, therefore an active control was not possible. Currently “treatment as usual” in most communities is watchful waiting (33). Next, in order to maintain subjects in a non-treatment arm, a WL condition that offered the active treatment after the waiting period has proven to be the most feasible as opposed to watchful waiting/treatment as usual. Therefore, those on the WL were offered PCIT-ED upon completion of the waiting period if the child remained symptomatic (see supplemental Figure 1). For the primary analyses, participants randomized to treatment first were compared to those randomized to the WL.

Recruitment/Screening

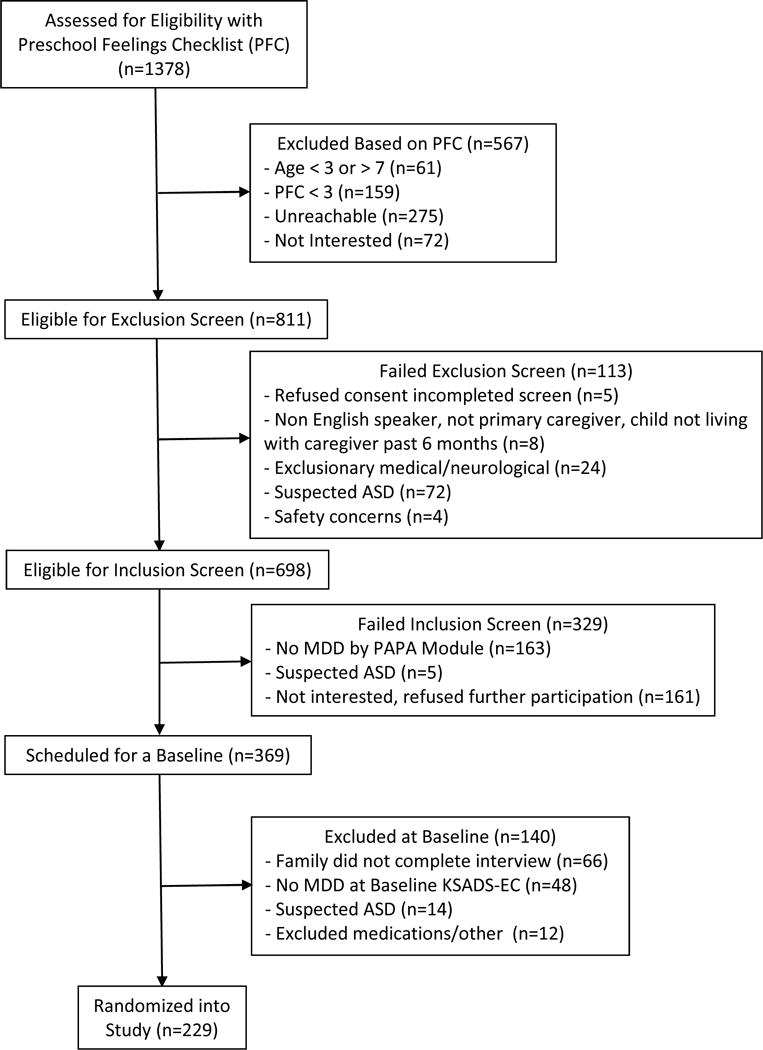

All study materials and procedures were approved in advance by the WUSM institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all caregivers with verbal assent obtained from children. The trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov. Young children (aged 3.0-6.11) from the St. Louis metropolitan area were screened and recruited from preschools, daycares, primary care, and mental health facilities. We obtained N=1378 Preschool Feelings Checklists (PFC), a validated brief screening measure with good sensitivity and specificity for early childhood depression (34). Those with a score > 3 (N=811) had a more comprehensive phone screen in which the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) MDD module was administered and exclusions were assessed. All children meeting early onset MDD symptom criteria on the PAPA (the validated syndrome which requires 4 instead of 5 symptoms of MDD) and who did not have an Autism Spectrum Disorder, a serious neurological or chronic medical disorder, or a significant developmental delay were invited for an in-person assessment (N=369), (see Figure 1 for consort diagram).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram of PCIT-ED Study

Children on antidepressant medications or in ongoing psychotherapy were excluded due to their possible efficacy in ameliorating depression and the need to test the efficacy of PCIT-ED without augmentation from other treatments. However, those on stable doses of other psychotropic medications without antidepressant properties were not excluded (e.g. Guanfacine, stimulants). Preschoolers on unstable medication dosing (e.g., undergoing active medication titration) and those with unstable caregiving (no longterm stable caregiver) were excluded. Preschoolers who were too severely depressed to wait 18 weeks for treatment (e.g., child/family in acute/serious distress) were excluded and referred for immediate treatment due to the possibility of randomization to the WL. All dyads who passed these stages participated in a comprehensive mental health and emotional development baseline assessment at the WUSM EEDP (detailed below). Children who met criteria for early childhood MDD were randomized to PCIT-ED or WL, with randomization stratified by gender and comorbid externalizing disorders.

Baseline and Post Assessment Methods

Children and caregivers were scheduled for a 5-hour baseline assessment. Caregivers were interviewed using the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Early Childhod (K-SADS-EC) (35) to assess the child’s psychiatric symptoms and assign DSM-5 diagnoses. Caregivers also completed a battery of psychosocial questionnaires that assessed the child’s emotion regulation and guilt processing, parental psychopathology, parenting practices and stress.

Demographics

Income-to-Needs

The income-to-needs ratio was computed as the total family income at baseline divided by the federal poverty level, based on family size at baseline.

Depression and Comorbid Psychopathology/Impairment

K-SADS-EC

The K-SADS-EC is a semi-structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders adaptated for use in children aged 3.0-6.11. This measure has test re-test reliability and construct validity that generates both categorical and dimensional measures of DSM-5 Axis I disorders (16, 35). The presence and severity of MDD and other Axis I comorbidities were assessed at baseline and post treatment or WL. All K-SADS-EC interviews were conducted by master’s level clinicians, were videotaped, reviewed for reliability, and calibrated for accuracy. Satisfactory inter-rater reliability was established prior to onset of the study and kappas during the study were maintained on a monthly basis with overall kappas of K=0.74 for MDD; all diagnoses K= 0.88 achieved during the study period. The MDD core score was the number of core MDD symptoms endorsed on the K-SADS-EC.

Preschool Feelings Checklist – Screening and Scale Versions (PFC and PFC-Scale)

The PFC, a validated screening checklist with favorable sensitivity, was used to capture young children at high risk for MDD (34). The PFC-Scale, a 23-item Likert scale, adapted from the PFC, was administered at baseline and post assessments to measure depression severity via caregiver report (32).

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)

The CGAS is a standardized instrument that measures children’s global level of impairment completed by the clinician-rater.

Clinical GlobaI Impression – Global Improvment (CGI-I)

The CGI-I is a 7-point Likert scale widely used in treatment research that measures the blind clinician-rater’s impression of improvement at post assessment.

Preschool and Early Childhood Functional Assessment Scale/Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (PECFAS/CAFAS)

The PECFAS and CAFAS is a semi-structured measure of functioning rated by the clinician (who achieves reliability prior to administration). It assess the child’s psychosocial functioning and impairment based on parent report of the child’s functioning in specific domains and information gleaned from the KSADS-EC.

Child’s Emotion Regulation and Guilt Processing

The Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC)

The ERC is a caregiver report measure of children’s self-regulation which targets affective lability, intensity, valence, and flexibility and includes both positively and negatively weighted items on a Likert scale.

My Child

The My Child is a widely used caregiver report measure with established validity and reliability of the child’s tendency to experience guilt and how the child addresses these feelings.

Parenting Style, Stress and Depression Severity

Parenting Stress Index (PSI)

The PSI, a reliable and valid measure designed to measure the magnitude of stress within the parent-child dyad via caregiver report.

Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions (CCNES)

The CCNES is a valid and reliable caregiver report measure of parental coping styles and strategies in response to children’s expression of negative emotions.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II, a reliable and valid self-report measure, was used to assess severity of depression in caregivers.

Randomization Procedures

The SAS procedure PLAN was used to generate a randomization table for each combination of the 2 stratifying variables. A permuted block design was utilized so that group assignment would be relatively balanced among each of the 4 stratification groups (male/externalizing comorbidity, male/no externalizing comorbidity, female/externalizing comorbidity, female/no externalizing comorbidity). The randomization assignments were created before the study began and saved in a password-protected Excel file that only the data manager had access to. Prior to randomization, the assignments were concealed to all study personnel outside of the data manager.

Blinding of Post-Treatment or Wait List Assessment

Upon treatment or WL completion, a post assessment was conducted during which time the above assessments were repeated. All clinician-administered ratings (e.g., K-SADS-EC, measures of impairment) were completed by independent raters (master’s level clinicians) who were blind to treatment group and otherwise uninvolved in the study (see supplement for more details about maintaining the blind). Further, families were instructed not to reveal their group assignment to the rater and to avoid use of treatment language or terminology. Events where the blind was broken were tracked.

Overview of Treatment

Parent Child Interaction Therapy-Emotion Development (PCIT-ED)

Parent Child Interaction Therapy-Emotion Development (PCIT-ED) is a dyadic parent-child psychotherapy expanded and adapted from the well-validated and widely used PCIT (30). A novel Emotion Development (ED) module was added and follows completion of standard PCIT modules that were limited to 12 sessions. The 8 session ED module builds on empirical findings in emotional development utilizing the basic techniques of PCIT (teaching of parent followed by coaching the parent in interactions with the child in vivo using a bug-in-the-ear device) to focus on enhancing the child’s emotional competence (36) and emotion regulation (37). This approach addresses early childhood depression as a disorder of emotional development characterized by impairments in the ability to recognize, understand, and regulate emotions in self and others, as well as targeting increased reactivity to negative and decreased reactivity to positive stimuli. The goal of enhancing these skills is achieved by training the parent to serve as a more effective external emotion regulator and emotion coach for the child. Therefore, the ED module directly targets the parents’ skill as an emotion teacher and facilitator for the child. To achieve this, discussion of challenging emotional situations and real-life events as well as emotionally evocative events in vivo are used, during which therapists coach the parent to use a skill set that validates and tolerates the child’s emotions and assists the child in regulating intense emotions. The length of the manualized treatment is 20 sessions conducted over 18 weeks. Therapist training and intervention fidelity monitoring procedures as well as number of sessions completed are described in detail in supplemental material.

Analysis

Baseline demographic, diagnostic and severity characteristics were compared in PCIT-ED and WL groups using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for dichotomous variables. The primary outcome measure of MDD diagnosis and the secondary outcomes MDD severity, PFC-Scale, CGAS, PECFAS/CAFAS, and BDI-II were analyzed in all randomized subjects using multiple imputation to ensure no missing values at the post assessment (38). MDD diagnosis was analyzed using logistic regression, and the continuous measures were analyzed using general linear models. All models covaried for the baseline characteristic corresponding to the dependent variable and the stratificiation variables gender and baseline externalizing disorder. Details of the imputation methods are provided in supplemental material. Secondary analyses compared PCIT-ED and WL subjects who completed the post assessment, regardless of whether they completed all study assessments or therapy sessions prior to the post assessment. Like in the primary analyses, continuous post characteristics were analyzed using general linear models, and dichotomous post characteristics were analyzed using logistic regression. These models also covaried for baseline characteristics, gender, and baseline externalizing disorder.

Effect sizes for analyses of multiply imputed data were calculated using the imputed datasets. For continuous variables, means and standard deviations for the difference between baseline and post scores were obtained and averaged across the 25 datasets. Then, these statistics were used to compute Cohen’s d. An odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for post MDD diagnosis (the primary outcome) was computed using data from all 25 imputed datasets. For the completer analyses, effect size was calculated as follows. For continuous variables, the partial eta-squared was obtained from the general linear model that took covariates into account. In addition, Cohen’s d was calculated by comparing the change in scores from baseline to post in each group. For dichotomous variables, effect size was the odds ratio, which was reported with its 95% confidence interval.

With the completer sample sizes of N=91 WL and N=100 PCIT-ED subjects, a difference in rates of post MDD diagnosis of 19.5% could be detected with 90% power. To account for multiple comparisons, false discovery rate p-values were computed for each set of analyses.

RESULTS

The post assessment occurred 169.1 (SD=24.9) days after baseline in PCIT-ED and 139.2 (SD=11.0) days after baseline in WL; t=10.92, p<0.0001.

Table 1 details baseline demographic, maternal depression, and diagnostic and severity characteristics in PCIT-ED and WL subjects. Subjects in the WL group were significantly more impaired on the PFC-Scale.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics of Randomized PCIT-ED and Wait List Subjects

| Wait List (N=115)

|

PCIT-ED (N=114)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Demographics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p |

| Age | 5.28 | 1.13 | 5.14 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.3192 |

| Income-to-needs ratio | 2.85 | 1.35 | 3.13 | 1.31 | −1.55 | 0.1229 |

| % | N | % | N | χ2 | p | |

|

|

||||||

| Female gender | 36.5 | 42 | 33.3 | 38 | 0.26 | 0.6129 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 8.7 | 10 | 13.2 | 15 | 1.17 | 0.2790 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 71.3 | 82 | 82.5 | 94 | F.E. | 0.1033 |

| African-American | 14.8 | 17 | 7.9 | 9 | ||

| Asian | 0.0 | 0 | 0.9 | 1 | ||

| More than 1 race | 13.9 | 16 | 8.8 | 10 | ||

| Baseline Severity | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p |

|

| ||||||

| MDD core score | 5.71 | 1.51 | 5.49 | 1.47 | 1.13 | 0.2612 |

| PFC-Scale score | 41.58 | 11.22 | 38.75 | 9.58 | 2.05 | 0.0414 |

|

| ||||||

| CGAS score | 42.67 | 6.60 | 44.00 | 6.54 | −1.52 | 0.1304 |

| PECFAS/CAFAS | 11.88 | 3.53 | 11.91 | 4.04 | −0.05 | 0.9594 |

| Maternal Depression | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p |

|

| ||||||

| BDI-II score | 12.10 | 9.76 | 10.62 | 8.53 | 1.22 | 0.2254 |

| Baseline Consensus Diagnoses | % | N | % | N | χ2 | p |

|

| ||||||

| Major Depressive Disorder (or NOS) | 100.0 | 115 | 100.0 | 114 | ||

| Mania/Hypomania | 1.7 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | F.E. | 1.0000 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 42.6 | 49 | 39.5 | 45 | 0.23 | 0.6297 |

| ADHD (or NOS) | 33.0 | 38 | 46.3 | 30 | 1.24 | 0.2652 |

| ODD (or NOS) | 48.7 | 56 | 50.9 | 58 | 0.11 | 0.7413 |

| Conduct Disorder | 2.6 | 3 | 2.6 | 3 | F.E. | 1.0000 |

F.E. = Fisher’s Exact test

As seen in Table 2, results of analyses conducted on multiply imputed post data including all randomized children showed significant differences between PCIT-ED and WL groups for the primary outcome of MDD diagnosis and secondary outcomes, with PCIT-ED subjects showing decreased MDD severity. Post comparisons of MDD diagnosis, remission rates (defined by not meeting diagnostic criteria for MDD and a > 50% reduction in MDD core score from baseline to post) and depression severity, as well as comorbid diagnostic characteristics by PCIT-ED and WL subjects who completed the post assessment are shown in Table 3. PCIT-ED participants were significantly less likely than those on the WL to meet criteria for MDD in the last month, more likely to have achieved remission and to score lower on MDD severity based on the K-SADS sum scores (Cohen’s d: 1.02) and PFC-Scale (Cohen’s d: 1.11). They were also less impaired than WL subjects on the CGAS (Cohen’s d: 1.16) and PECFAS/CAFAS (Cohen’s d: 0.91). Global improvement, measured with the CGI-I, indicated significant improvement from baseline to post in PCITED subjects compared to WL (Cohen’s d: 1.25). In addition, post assessment rates of comorbid disorders, including anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, were significantly lower in the PCIT-ED group.

Table 2.

Post Assessment Characteristics* in Randomized PCIT-ED and Wait List Subjects

| Wait List vs. PCIT-ED

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | Estimate | SE | t | p | FDR p | OR (95% CI) |

| Major Depressive Disorder (or NOS) | 1.20 | 0.18 | 6.60 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 9.52 (8.44, 10.74) |

| Secondary Outcomes | Estimate | SE | t | p | FDR p | Cohen’s d |

|

| ||||||

| MDD core score | 2.34 | 0.26 | 9.11 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.01 |

| PFC-Scale score | 11.91 | 1.29 | 9.26 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.04 |

| CGAS score | −20.49 | 2.31 | −8.87 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.16 |

| PECFAS/CAFAS | 3.19 | 0.46 | 6.91 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.78 |

| BDI-II score | 2.04 | 0.76 | 2.68 | 0.0074 | 0.0074 | 0.24 |

Missing post data were imputed using multiple imputation; Cohen’s d is for the change from baseline to post averaged across 25 imputed datasets; OR = odds ratio combining data from 25 imputed datasets; FDR = false discovery rate; Analyses covary for baseline characteristics, gender, and baseline externalizing disorder.

Table 3.

Post Assessment Severity and Diagnostic Characteristics in PCIT-ED and Wait List Subjects Completing the Post Assessment

| Wait List (N=91)

|

PCIT-ED (N=100)

|

Wait List vs. PCIT−ED

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome: MDD Diagnosis | % | N | % | N | χ2 | p | FDR p | OR | 95% CI |

| Major Depressive Disorder (or NOS) | 74.7 | 68 | 22.0 | 22 | 46.92 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 12.15 | (5.95, 24.82) |

| Secondary Outcome: Remission | % | N | % | N | χ2 | p | FDR p | OR | 95% CI |

|

| |||||||||

| Remission of MDD* | 23.1 | 21 | 73.0 | 73 | 42.86 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.10 | (0.05, 0.20) |

| PFC−Scale reduced ≥50%, no MDD | 5.6 | 5 | 43.4 | 43 | 26.43 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.07 | (0.03, 0.20) |

| Secondary Outcome: Severity | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | FDR p | Partial η2 | Cohen’s d |

|

| |||||||||

| MDD core score | 4.15 | 2.04 | 1.74 | 1.69 | 9.11 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.31 | 1.02 |

| PFC-Scale score | 33.20 | 11.10 | 20.10 | 9.65 | 9.44 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.33 | 1.11 |

| Secondary Outcome: Severity | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | FDR p | Partial η2 | Cohen’s d |

|

| |||||||||

| CGAS score | 55.75 | 17.14 | 76.83 | 16.61 | −8.62 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.29 | 1.16 |

| PECFAS/CAFAS | 8.07 | 4.02 | 4.83 | 3.22 | 7.15 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.23 | 0.91 |

| CGI-I score | 3.40 | 1.25 | 2.07 | 0.86 | 8.67 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.29 | 1.25 |

| Mania/Hypomania | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Anxiety Disorder | 26.4 | 24 | 10.1 | 10 | 10.37 | 0.0013 | 0.0014 | 4.52 | (1.80, 11.31) |

| ADHD (or NOS) | 22.0 | 20 | 13.1 | 13 | 1.50 | 0.2211 | 0.2211 | 1.72 | (0.72, 4.12) |

| ODD (or NOS) | 38.5 | 35 | 14.1 | 14 | 16.95 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 5.95 | (2.55, 13.89) |

| Conduct Disorder | 1.1 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

Cohen’s d is for the change from baseline to post; FDR = false discovery rate; OR = odds ratio;

Remission defined as not meeting diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and a 50% or greater reduction in MDD core score from baseline to post; Analyses covary for baseline characteristics, gender, and baseline externalizing disorder.

PCIT-ED subjects also differed significantly from WL subjects at post on measures of emotional development and regulation. Specifically, at the post assessment, PCIT-ED subjects were rated by their caregivers as exhibiting less emotional lability (29.2±6.4 vs. 37.2±7.6, t=−9.83, p<0.0001, Cohen’s d=1.21) and more emotion regulation (26.4±3.5 vs. 24.1±3.3, t=5.36, p<0.0001, Cohen’s d=0.69), as well as greater guilt reparation (27.4±5.3 vs. 24.7±5.0, t=5.13, p<0.0001, Cohen’s d=0.70). There were significant differences in parental characteristics between PCIT-ED and WL subjects at the post assessment, with parents who completed PCIT-ED having decreased personal symptoms of depression and lower scores on parenting stress in addition to employing more parenting techniques that focused on emotion reflection and processing (see Table 4). The correlation between change in maternal BDI-II and change in child PFC-Scale from baseline to post was was 0.387 (p<0.0001) in the PCIT-ED group. Baseline comparisons for emotion, cognitive, executive, and parenting characteristics are shown in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. The treatment was rated by parents as highly acceptable based on the Eyberg Therapy Attitude Inventory with an overall mean (SD) rating of 67.3 (6.4) out of a 75 with 96% of parents reporting a score of “good” or “very good” for their impression of the therapy program.

Table 4.

Post Assessment Parenting Characteristics in PCIT−ED and Wait List Subjects Completing the Post Assessment

| Wait List (N=90)

|

PCIT−ED (N=96)

|

Wait List vs. PCIT−ED

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting Stress Index | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | FDR p | Partial η2 | Cohen’s d |

| Distractibility/hyperactivity | 27.72 | 7.54 | 21.16 | 6.34 | 7.04 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | 0.79 |

| Adaptability | 29.60 | 6.20 | 25.29 | 5.77 | 6.52 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.19 | 0.90 |

| Reinforces parent | 11.09 | 4.27 | 9.41 | 3.36 | 3.46 | 0.0007 | 0.0014 | 0.06 | 0.39 |

| Demandingness | 26.79 | 7.28 | 21.71 | 6.77 | 5.48 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.70 |

| Mood | 18.51 | 3.63 | 14.48 | 4.03 | 7.83 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.25 | 1.02 |

| Acceptability | 13.61 | 2.47 | 11.35 | 2.93 | 5.01 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.12 | 0.53 |

| Child domain | 127.33 | 24.77 | 103.40 | 22.66 | 8.00 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.26 | 1.06 |

| Competence | 29.07 | 7.58 | 26.63 | 7.19 | 1.75 | 0.0822 | 0.1132 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Isolation | 14.38 | 5.19 | 12.84 | 4.39 | 2.52 | 0.0125 | 0.0229 | 0.03 | 0.30 |

| Attachment | 12.38 | 4.37 | 11.33 | 3.52 | 1.20 | 0.2333 | 0.2851 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Health | 11.64 | 3.78 | 10.77 | 3.85 | 0.74 | 0.4617 | 0.5227 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Role restriction | 18.46 | 6.14 | 17.96 | 5.35 | 0.57 | 0.5675 | 0.5675 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Depression | 20.73 | 6.67 | 19.08 | 5.94 | 1.75 | 0.0823 | 0.1132 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Spouse | 18.10 | 7.08 | 17.83 | 6.86 | −0.68 | 0.4989 | 0.5227 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Life stress | 5.38 | 6.21 | 4.77 | 7.35 | 0.70 | 0.4823 | 0.5227 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| Parent domain | 124.73 | 31.32 | 116.45 | 29.37 | 1.26 | 0.2076 | 0.2687 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Total stress | 252.07 | 49.19 | 219.84 | 47.23 | 5.04 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.12 | 0.70 |

| Defensive responding | 36.83 | 11.04 | 34.28 | 10.09 | 1.98 | 0.0488 | 0.0767 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

|

Wait List (N=91)

|

PCIT−ED (N=100)

|

Wait List vs. PCIT−ED

|

|||||||

| Parental Depression | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | FDR p | Partial η2 | Cohen’s d |

|

| |||||||||

| BDI−II score | 8.87 | 8.98 | 6.14 | 7.17 | 2.36 | 0.0195 | 0.0330 | 0.03 | 0.24 |

|

Wait List (N=91)

|

PCIT−ED (N=100)

|

Wait List vs. PCIT−ED

|

|||||||

| Parental Depression | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | FDR p | Partial η2 | Cohen’s d |

|

| |||||||||

| Expressive encouragement | 5.22 | 1.24 | 6.00 | 0.88 | −6.22 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.81 |

| Emotion−focused reactions | 5.84 | 0.83 | 5.42 | 1.03 | 3.94 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.08 | 0.56 |

| Minimization reactions | 2.13 | 0.78 | 1.69 | 0.65 | 5.58 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.70 |

Cohen’s d is for the change from baseline to post; FDR = false discovery rate; Lower scores on the PSI represent more adapative behavior; Analyses covary for baseline characteristics, gender, and baseline externalizing disorder.

DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled trial compared a parent-child psychotherapy, an adaptation of PCIT with a new module focused on emotional development (PCIT-ED), to a WL control condition for the treatment of early childhood depression. The findings show that treatment was effective in producing remission of depression and marked decreases in depression severity compared to those in the WL group. In addition to this, children who received PCIT-ED also showed marked improvements in general functioning and decreases in impairment. To our knowledge, this is the first empirically supported psychotherapeutic intervention specific to early childhood depression. Based on its efficacy and effect sizes, this treatment now represents an important new low-risk and effective option for the treatment of early childhood depression. Other important features of this intervention that make it highly feasible and cost effective for public health delivery are that it can be delivered by trained master’s level therapists, and that it is a relatively brief, 20 session manualized treatment.

In addition to remediation of depression and marked reductions in impairment, children who received PCIT-ED also showed improvements in emotional functioning in areas directly targeted by the treatment, specifically emotion regulation and guilt processing. Emotion dysregulation and excessive guilt with low ability for pro-active reparation are known features of early childhood depression (39). The findings of this study suggest that these emotion development targets, key to affective disorders and functioning more generally, are modifiable in early childhood. It will be important to determine if gains in these emotional parameters are sustained over time as is often seen in other early developmental interventions including standard PCIT.

This parent-child treatment, which also focused on modifying parenting, had marked positive effects on parenting stress and depression experienced by caregivers. Parents who received the active treatment displayed more emotionally focused parenting techniques and reported marked reductions in stress and a greater sense of positive responsiveness from their child. Also notable was that the treatment resulted in significant reductions in parental depression, even though this was not a direct target of treatment. This is consistent with findings from an earlier pilot study of PCIT-ED (32) and may represent a virtuous cycle whereby child depression remission results in parental depression improvements, a new direction of effect, as the reverse direction has been previously documented (40). These findings taken together suggest a number of positive benefits for parents from the treatment.

The use of a WL control was a limitation of the current study. While effect sizes were relatively large, a WL control does not provide a formidable comparison condition. However, in a disorder/age group for which there was no available empirically proven treatment, this was a necessary first step. Future studies will be needed to compare PCIT-ED to other more active conditions to better estimate clinically meaningful effects that can be compared to treatments in older children (where effect sizes generated may be based on active comparisons). In addition, a short follow-up period is another limitation. It will be important to test how gains made in treatment endure over time. Such a longitudinal follow-up would provide a test of the additional value of early intervention from a lifespan perspective.

While PCIT itself has been established as a powerfully effective intervention for early childhood disruptive behavior, it has not previously been tested for the treatment of depression. Further, few studies have investigated parent-child psychotherapies for their efficacy for clinical level diagnoses in early childhood. Related to this, another finding was that comorbid disorders including oppositional disorder and anxiety disorders were also significantly reduced as a result of treatment. Study findings suggest that early intervention for depression may be a window of opportunity to modify emotional functioning, utilizing the powerful influence of the parent-child relationship during this relatively neuroplastic developmental period to remediate depressive symptoms. Given that depression is a chronic and relapsing disorder, these findings using an early psychotherapeutic intervention with low cost and low risk suggest that early identification and treatment of depressive disorders should now become a public health priority.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The National Institute of Mental Health, Grant # 5R01MH098454-04

References

- 1.Luby JL, Heffelfinger AK, Mrakotsky C, Hessler MJ, Brown KM, Hildebrand T. Preschool major depressive disorder: preliminary validation for developmentally modified DSM-IV criteria. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(8):928–37. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luby JL, Heffelfinger AK, Mrakotsky C, Brown KM, Hessler MJ, Wallis JM, et al. The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):340–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luby JL, Mrakotsky C, Heffelfinger A, Brown K, Spitznagel E. Characteristics of depressed preschoolers with and without anhedonia: evidence for a melancholic depressive subtype in young children. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1998–2004. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luby JL, Belden AC, Pautsch J, Si X, Spitznagel E. The clinical significance of preschool depression: impairment in functioning and clinical markers of the disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2009;112(1–3):111–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2006;47(3–4):313–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wichstrom L, Berg-Nielsen TS, Angold A, Egger HL, Solheim E, Sveen TH. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2012;53(6):695–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavigne JV, Lebailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology: the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2009;38(3):315–28. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleason MM, Zamfirescu A, Egger HL, Nelson CA, 3rd, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in very young children in a Romanian pediatric setting. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(10):527–35. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E. Preschool depression: homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Archives of general psychiatry. 2009;66(8):897–905. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, Rose S, Klein DN. Psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: continuity from ages 3 to 6. The American journal of psychiatry. 2012;169(11):1157–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaffrey MS, Luby JL, Repovs G, Belden AC, Botteron KN, Luking KR, et al. Subgenual cingulate connectivity in children with a history of preschool-depression. Neuroreport. 2010;21(18):1182–8. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834127eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luking KR, Repovs G, Belden AC, Gaffrey MS, Botteron KN, Luby JL, et al. Functional connectivity of the amygdala in early-childhood-onset depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):1027–41 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barch DM, Gaffrey MS, Botteron KN, Belden AC, Luby JL. Functional brain activation to emotionally valenced faces in school-aged children with a history of preschool-onset major depression. Biological psychiatry. 2012;72(12):1035–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaffrey MS, Luby JL, Belden AC, Hirshberg JS, Volsch J, Barch DM. Association between depression severity and amygdala reactivity during sad face viewing in depressed preschoolers: an fMRI study. Journal of affective disorders. 2011;129(1–3):364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaffrey MS, Barch DM, Singer J, Shenoy R, Luby JL. Disrupted amygdala reactivity in depressed 4to 6-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(7):737–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaffrey MS, Barch DM, Bogdan R, Farris K, Petersen SE, Luby JL. Amygdala reward reactivity mediates the association between preschool stress response and depression severity. Biological psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belden AC, Irvin K, Hajcak G, Kappenman ES, Kelly D, Karlow S, et al. Neural Correlates of Reward Processing in Depressed and Healthy Preschool-Age Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(12):1081–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.09.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(1):132–49. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyman SE. Can neuroscience be integrated into the DSM-V? Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(9):725–32. doi: 10.1038/nrn2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. The American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawson G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(3):775–803. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: a comparison of child and parent training interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(1):93–109. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology: the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2004;33(1):105–24. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson MH. Sensitive periods in functional brain development: problems and prospects. Developmental psychobiology. 2005;46(3):287–92. doi: 10.1002/dev.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeBar LL, Lynch F, Powell J, Gale J. Use of psychotropic agents in preschool children Associated symptoms, diagnoses, and health care services in a health maintenance organization. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157(2):150–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rushton JL, Whitmire JT. Pediatric stimulant and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescription trends: 1992 to 1998. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(5):560–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. Jama. 2000;283(8):1025–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Soeken K, Boles M, et al. Rising prevalence of antidepressants among US youths. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):721–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):13–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyberg SM, Funderburk BW, Hembree-Kigin TL, McNeil CB, Querido JG, Hood KK. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with behavior problem children: One and two year maintenance of treatment effects in the family. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2001;23(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27(2):180–9. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luby J, Lenze S, Tillman R. A novel early intervention for preschool depression: findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2012;53(3):313–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedland KE, Mohr DC, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Usual and unusual care: existing practice control groups in randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(4):323–35. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218e1fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught AL, Brown K, Spitznagel E. ThePreschool Feelings Checklist: a brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):708–17. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaffrey MS, Luby JL. Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Early Childhood Version, 2012 Working Draft (KSADS-EC) 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saarni C. The Development of Emotional Competence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenze SN, Pautsch J, Luby J. Parent-child interaction therapy emotion development: a novel treatment for depression in preschool children. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(2):153–9. doi: 10.1002/da.20770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little RJ, D’agostino R, Cohen ML, Dickersin K, Emerson SS, Farrar JT, et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(14):1355–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luby J, Belden A, Sullivan J, Hayen R, McCadney A, Spitznagel E. Shame and guilt in preschool depression: evidence for elevations in self-conscious emotions in depression as early as age 3. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2009;50(9):1156–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Pilowsky DJ, Poh E, Batten LA, Hernandez M, et al. Treatment of maternal depression in a medication clinical trial and its effect on children. The American journal of psychiatry. 2015;172(5):450–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.