Abstract

Background

The explosive growth in known human gene variation presents enormous challenges to current approaches for variant classification that have implications for diagnosis and treatment of many genetic diseases. For disorders caused by mutations in cardiac ion channels as in congenital arrhythmia syndromes, in vitro electrophysiological evidence has high value in discriminating pathogenic from benign variants, but these data are often lacking because assays are cost-, time- and labor-intensive.

Methods

We implemented a strategy for performing high throughput, functional evaluations of ion channel variants that repurposed an automated electrophysiological recording platform developed previously for drug discovery.

Results

We demonstrated success of this approach by evaluating 78 variants in KCNQ1, a major gene involved in genetic disorders of cardiac arrhythmia susceptibility. We benchmarked our results with traditional electrophysiological approaches and observed a high level of concordance. This strategy also enabled studies of dominant-negative behavior of variants exhibiting severe loss-of-function. Overall, our results provided functional data useful for reclassifying more than 65% of the studied KCNQ1 variants.

Conclusions

Our results illustrate an efficient and high throughput paradigm linking genotype to function for a human cardiac ion channel that will enable data-driven classification of large numbers of variants and create new opportunities for precision medicine.

Keywords: Genetics, Arrhythmias, Sudden Cardiac Death, Basic Science Research, Ion Channels/Membrane Transport, ion channel, mutation, gene mutation, long QT syndrome, potassium channels

INTRODUCTION

The widespread use of genetic and genomic testing in research and clinical medicine has led to explosive growth in the number of gene variants associated with human diseases and in reference populations. This has led to an emerging challenge to classify variants accurately with respect to potential pathogenicity. The interpretation of clinical genetic tests are often confounded by ‘variants of unknown significance’ (VUS), a term indicating that there are insufficient data to distinguish between disease-causing mutations and benign variants.1 Several computational tools have been developed to predict which coding sequence variants may be deleterious,2 but these methods have not been systematically validated and results from such analyses are deemed to have lower value than experimental evidence for classifying variants in the clinical setting.3 There has been a recent call for expanded efforts to functionally annotate variants,4 but not all genes are equally amenable to large scale functional studies.

Human genetic diseases caused by mutations in ion channels (channelopathy)5 represent unique opportunities to meet the challenge of variant annotation because well-established in vitro functional assay paradigms exist for these proteins. The standard approach for determining the functional properties of an ion channel variant is cellular electrophysiology using patch-clamp recording of heterologously expressed recombinant channels. However the usual embodiment of this method is tedious, time- and labor-intensive, making it too low throughput for determining the functional consequences of more than a few variants at a time.

One channelopathy that illustrates the challenge of variant classification is the congenital long-QT syndrome (LQTS), an inherited predisposition to sudden cardiac death affecting children and young adults 6–8 with a population incidence of approximately 1 in 2500.9 As with many other inherited disorders, clinical genetic testing has become standard-of-care for LQTS.10,11 Nearly 50% of LQTS cases are associated with genetic variants in KCNQ112 that encodes the voltage-gated potassium channel KV7.1, which complexes with an accessory subunit encoded by KCNE1 to generate the slow delayed rectifier current (IKs) essential for normal myocardial repolarization.13,14 In addition to LQTS, at least two other genetic arrhythmia syndromes, short QT syndrome15,16 and familial atrial fibrillation,17,18 as well as cases of sudden infant death syndrome19–21 are associated with KCNQ1 mutations. There are currently more than 600 known disease-associated KCNQ1 variants,22 but only a small fraction has been analyzed functionally. Further, there are many rare KCNQ1 variants found in population genome sequence databases, some of which have minor allele frequencies lower than the estimated population prevalence of LQTS, such that their possible pathogenicity cannot be ruled out. Accurately discriminating pathogenic KCNQ1 mutations from benign variants has actionable consequences for diagnosis, treatment, prognosis and family counseling. Functional annotation of KCNQ1 variants would offer strong supporting evidence for variant classification.

To overcome the challenge of determining the function of hundreds of ion channel variants, we coupled two advanced technologies: high efficiency cell electroporation and automated planar patch clamp recording. In this study, we demonstrated the capabilities of this approach by investigating the functional consequences of 78 KCNQ1 variants parsed into training (30 variants) and test (48 variants) sets. Our study offers a new paradigm for the functional evaluation of ion channel gene variants using a high throughput experimental approach and represents a milestone in the application of automated cellular electrophysiology.

METHODS

All data, analytical methods, and study materials supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures. A full description of the methods is provided in the online Supplemental Material.

RESULTS

Coupling high efficiency cell electroporation to automated electrophysiology

Unlike manual patch clamp recording, which affords an opportunity to select cells by microscopy, automated electrophysiology is performed without direct visualization. This precludes the typical use of fluorescent or other co-transfection markers to identify cells at the time of experiments. Generating cell lines stably expressing a protein of interest is the usual solution to this problem, but substantial time and cost barriers are incurred when analyzing hundreds of variants. To overcome this obstacle, we implemented a high efficiency cell electroporation method for transiently co-expressing plasmids encoding KCNQ1 and its accessory subunit, KCNE1, suitable for automated electrophysiology (see Methods). We expressed channel subunits from plasmid vectors encoding either green (EGFP coupled to KCNQ1) or red (DsRed coupled to KCNE1) fluorescent proteins to enable quantification of transfection efficiency by flow cytometry.

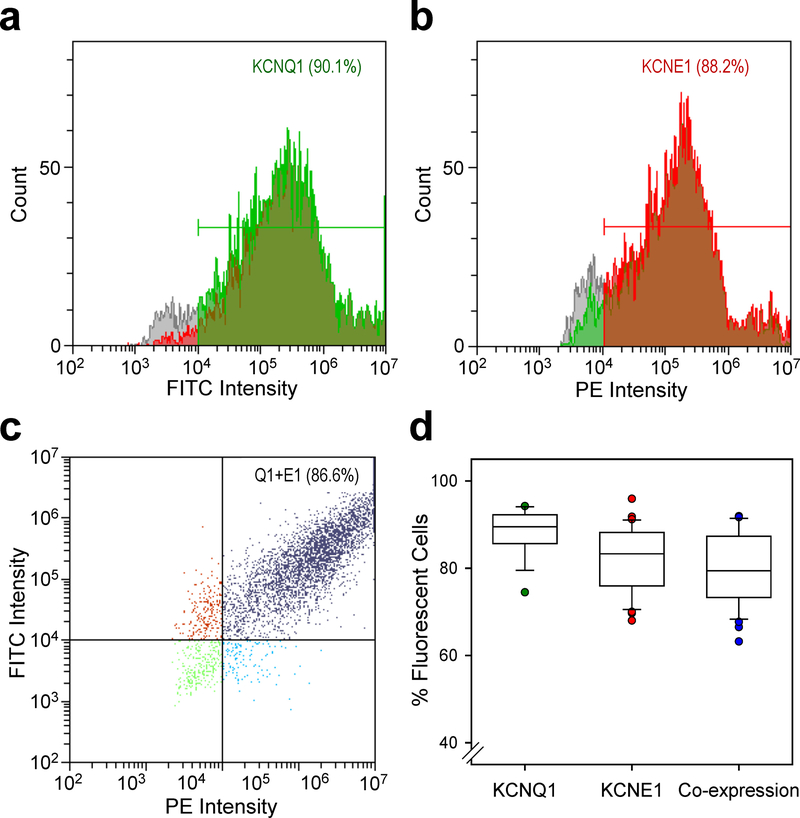

Optimized co-transfection efficiency and cell survival were obtained by electroporating 30 µg KCNE1 with 15 µg KCNQ1 plasmids into Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells. Under these conditions, we obtained 88.2 ± 5.4% (mean ± S.D.) transfection efficiency for WT KCNQ1 (inferred by the proportion of green fluorescent cells) and 81.9 ± 7.3% transfection efficiency for KCNE1 (red fluorescence) resulting in a co-transfection efficiency of 80.0 ± 8.2% with an average cell viability of 94.2 ± 6.8% (n = 32 transfections; Fig. 1). Non-transfected CHO-K1 cells lacked inherent green or red fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. S1), thus eliminating concern for false positives or over-estimation of transfection efficiencies by flow cytometry. Serial analysis demonstrated a high degree of reproducibility of these results. Cells were cultured for 48 h after electroporation then cryopreserved. Sufficient numbers of cells survived each electroporation to enable at least two automated electrophysiology experiments.

Figure 1: Efficiency of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 electroporation.

Representative plots of fluorescence intensity vs cell counts measured by flow cytometry for CHO cells co-transfected with KCNQ1 (a, green fluorescence, FITC) and KCNE1 (b, red fluorescence, PE). The percentage of fluorescent cells is indicated within the panels. c) Plot of FITC vs PE intensity illustrating efficiency of KCNQ1 (Q1) and KCNE1 (E1) co-transfection (purple dots, upper right quadrant). d) Box plots illustrating the range of transfection efficiencies for KCNQ1, KCNE1 and co-expression for 32 separate electroporation experiments. Each box height represents the 25th to 75th percentile and the error bars represent the 5th to 95th percentile. Individual data points falling outside the 5–95th percentile range are plotted. Black and colored horizontal lines within each box indicate the median and mean values, respectfully.

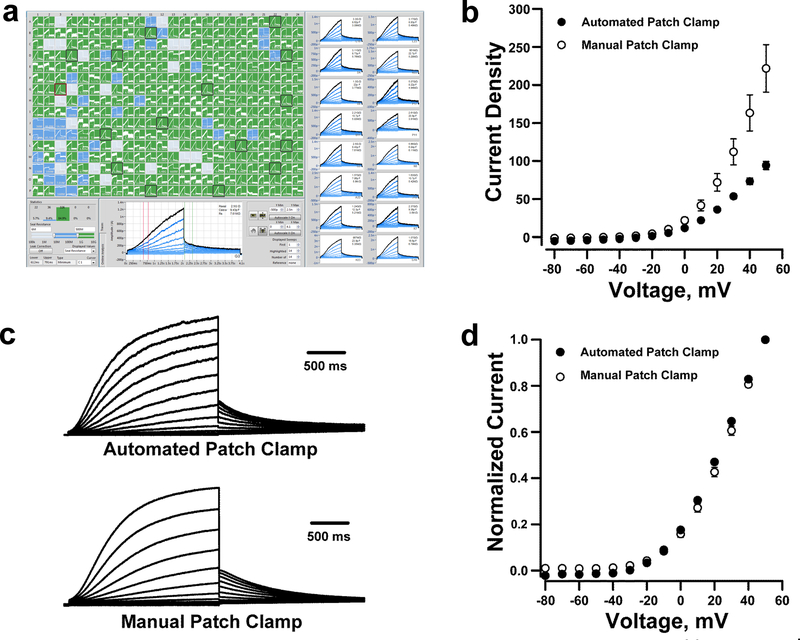

We recorded robust whole-cell current with properties consistent with IKs from cells electroporated with KCNQ1 and KCNE1 plasmids using an automated, dual 384-well planar patch clamp system (see Methods; Fig. 2A). To eliminate background currents, we applied the selective IKs blocker HMR155623,24 at the end of each experiment and performed offline subtraction of HMR1556-insensitive current. None of the KCNQ1 variants we examined in this study were HMR1556-resistant. In a typical experiment, cells were captured in ~96% of plate wells (blue and green shaded wells, Fig. 2A) and ~300 (80% of 384-well plate) cells had seal resistance ≥0.5 GΩ (green shaded wells, Fig. 2A). The averaged peak current density measured by automated patch clamp was lower than that measured by manual patch clamp (Fig. 2B). However, the averaged whole-cell currents normalized to the maximum peak current amplitude exhibited nearly identical gating kinetics measured by the two approaches (Fig. 2C) and had indistinguishable apparent half-maximal activation voltages (V½) (manual patch clamp: V½ = 23.0 ± 1.0 mV, n = 19; automated patch clamp: V½ = 24.5 ± 0.6 mV, n = 250; p = 0.5; Fig. 2D). Rundown of IKs was not significantly different between manual and automated patch clamp (Supplemental Fig. S2a). Smaller peak current amplitudes recorded by automated patch clamp are partly explained by the unbiased selection of cells for recording in contrast to manual patch clamp in which the operator selects cells based on visually detectable fluorescence with a bias toward cells exhibiting bright fluorescence and, by inference, high channel expression. Overall, these results demonstrated that WT IKs recorded from electroporated cells by automated patch clamp is comparable to measurements made using manual patch clamp.

Figure 2: Automated patch clamp recording of wild type KCNQ1.

A. Screen-shot of automated whole-cell current planar patch clamp recordings from CHO-K1 cells electroporated with plasmids encoding wild type (WT) KCNQ1 and KCNE1. The panels on the right highlight 16 out of the 384 wells that show whole-cell currents with IKs-like kinetics. B. Current density-voltage relationships obtained from CHO-K1 cells transfected with KCNQ1 and KCNE1 recorded by automated (⚫, n = 250) or manual (⚪, n = 19) patch clamp. Whole-cell currents are normalized by membrane capacitance (units are pA/pF). c) Average whole-cell currents recorded from cells electroporated with KCNQ1 and KCNE1 recorded using automated (top) or manual (bottom) patch clamp and normalized to the maximum peak current at +60 mV. d) Voltage-dependence of activation curves obtained from whole-cell currents recorded using automated (⚫) or manual (⚪) patch clamp.

Training and validation

We further validated and optimized throughput of the method using a training set of 30 disease-associated and non-disease associated KCNQ1 variants. The disease-associated variants included 17 variants (15 associated with LQTS; Supplemental Table S2) for which there were available functional data obtained using conventional (manual) electrophysiological approaches either from published reports or our laboratory. The non-disease associated set was comprised of 13 variants designed to match evolutionary substitutions found in orthologous KCNQ1 proteins from 12 different species (Supplemental Fig. S3), which we predicted would largely preserve channel function in contrast to many of the disease-associated variants that cause loss-of-function. Most of the variants chosen for this analysis affected residues located within the KCNQ1 voltage-sensing domain (VSD, residues 100–248; Supplemental Fig. S4). Variants were engineered into the KCNQ1 plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis and then co-electroporated with KCNE1 into CHO-K1 cells prior to automated patch clamp recording experiments (see Methods).

A typical experiment consisted of a 384-well planar patch plate loaded with five distinct KCNQ1 variants, each seeded into 64 wells along with a separate cluster of wells with cells expressing either WT-KCNQ1 as a positive control or non-transfected cells as a negative control (average transfection efficiencies determined by flow cytometry were 80.6 ± 6.8%, 74.2 ± 8.0% and 68.9 ± 7.6% for KCNQ1, KCNE1 and co-transfections, respectively; average viability was 88.8 ± 6.7%). Data from eight 384-well plates were sufficient to generate data for all 30 variants with dense replication (average number of successful replicates: n = 56 for variants, n = 301 for WT cells, and n = 220 for non-transfected cells). In these experiments, 94.4 ± 0.7% of wells exhibited cell capture with 80.4 ± 2.7% achieving a seal resistance of ≥ 0.5 GΩ yielding 1,976 cells that met stringent criteria and were used for analysis (see Methods).

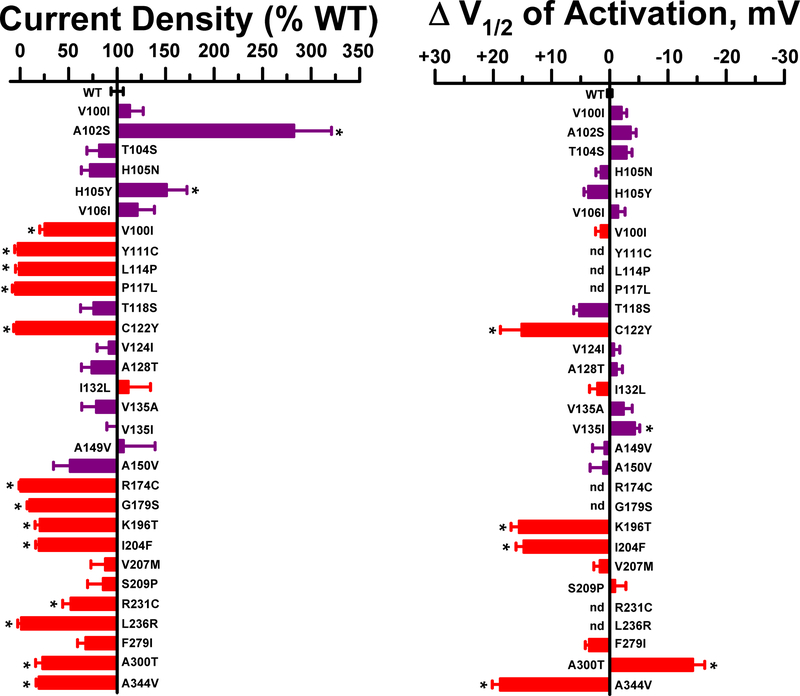

Figure 3A illustrates averaged HMR1556-sensitive whole-cell current density recorded at +60 mV from CHO-K1 cells expressing the disease-associated (red) or evolutionary substitution (magenta) variants in the training set expressed as percent of WT, whereas Supplemental Fig. S5 illustrates averaged whole-cell current traces for all variants. We defined specific criteria for functional classifications (Supplemental Table S3) based on an extensive review of publications reporting functional assessments of KCNQ1 variants associated with LQTS.25 Among the disease-associated KCNQ1 variants in the training set, most (12/17) generated current densities with small amplitudes (< 25% of WT) consistent with severe loss-of-function, which is the established molecular mechanism underlying LQTS.7 By contrast, 10 of the 13 evolutionary variants exhibited normal or near normal (defined as 70% to 130% of WT IKs) current amplitudes, with 1 variant yielding current density >180% of WT and two others showing moderate (~50% of WT) loss- or gain-of-function. The voltage-dependence of activation was determined for all training set variants having a current amplitude >10% of WT and expressed as the divergence in half-maximal voltage (ρV½) from WT (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: Functional properties of training set KCNQ1 variants recorded by automated patch clamp.

A. Average whole-cell currents recorded at +60 mV from cells expressing training set KCNQ1 variants plotted as percent of WT (n = 23–137). B. Difference in activation V½ relative to WT determined for variants with current amplitude >10% of WT (n = 4–79). KCNQ1 variants are ordered by codon number with red bars indicating disease-associated variants and magenta bars representing non-disease variants. Bar height indicates mean value and error bars are SEM (* indicates p ≤0.01).

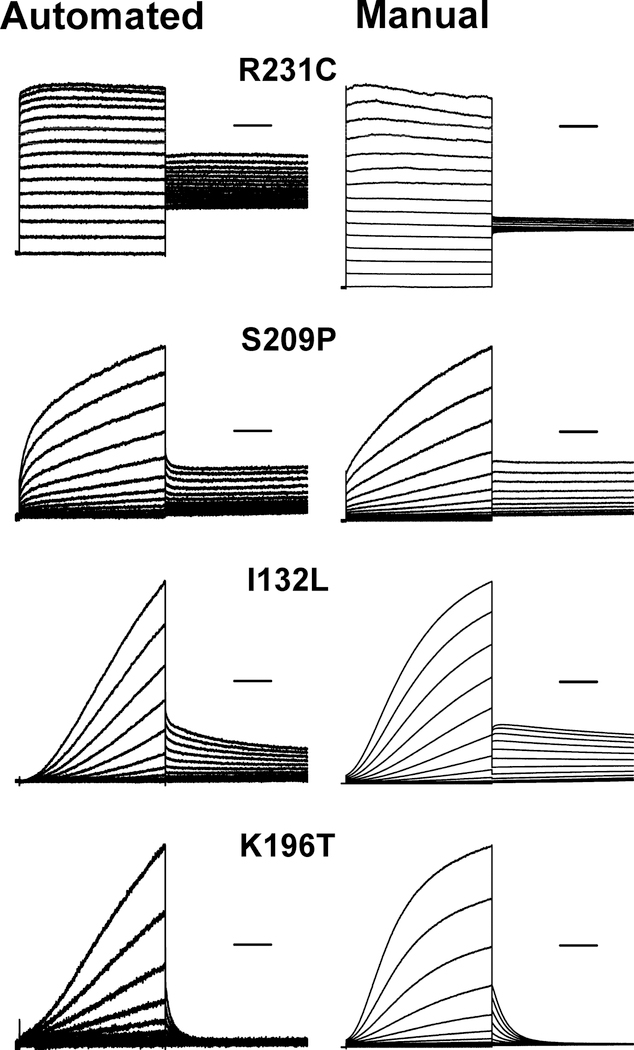

We also quantified the time course of deactivation by fitting current traces with exponential functions (Supplemental Table S4a). Variant R231C is notable for a markedly slower time course of deactivation compared with WT channels (Fig. 4) and this resembles published data obtained using manual patch clamp recording.26 Impaired deactivation was also observed for variants I132L and S209P, while faster deactivation was exhibited by K196T. Similar results were observed by manual patch clamp recording in our laboratory (Fig. 4; Supplemental Table S4b). None of the other functional training variants exhibited abnormal gating kinetics and this is consistent with literature reports.

Figure 4: KCNQ1 variants with altered gating kinetics.

Average whole-cell currents recorded from cells expressing select KCNQ1 variants by automated and manual patch clamp recording. Traces were normalized to peak current measured at +60 mV to enable comparison of gating behaviors among variants with divergent current density. Horizontal bars represent 500 ms. Time constants of deactivation are presented in Supplemental Table S4a (automated patch clamp) and Supplemental Table S4c (manual patch clamp). Only I132L exhibited a significant difference in deactivation time constant between the two methods when expressed as a % of WT channels determined on the same platform (automated: 170 ± 15%, n = 21; vs manual: 280 ± 51%, n = 7; p ≤ 0.01).

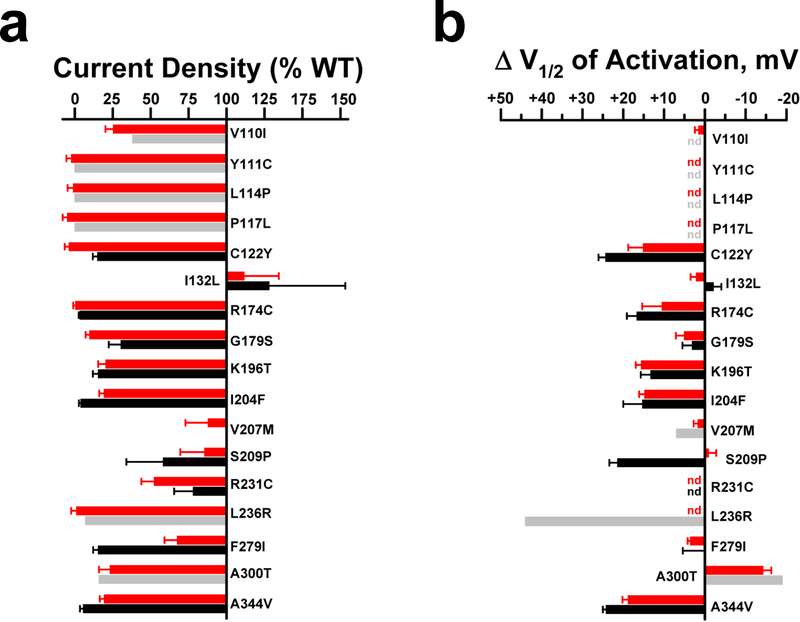

Comparisons of our findings obtained with automated patch clamp recording with published and unpublished data generated by manual patch clamp recording revealed a high degree of concordance (Fig. 5). With the exception of G179S, there were no significant differences in current density between the two methods, and no differences in activation V½ were observed for any variant. Impaired deactivation precluded reliable measurement of activation voltage-dependence for R231C by both automated and manual patch clamp recording. For similar reasons, we could not reliably determine activation V½ for S209P by manual patch clamp because of insufficient data, but this problem was overcome using automated patch clamp. We could not determine a V½ value for Y111C, L114P, P117L, and L236R because the recorded currents were too small.

Figure 5: Comparison of automated and manual patch clamp for KCNQ1 variants.

A. Average whole-cell current density for training set disease-associated KCNQ1 variants determined by automated (red bars) or manual (grey or black bars) patch clamp recording measured at +60 mV and expressed as percent of WT. For manual patch clamp, grey shaded bars are values derived from published reports (mean values only, see below for citations), and black shaded bars are data from this study (mean, SEM). Quantified functional parameters are provided in Supplemental Tables S4a and S4b, and the asterisk indicates p ≤ 0.01. B. Differences in activation V½ relative to WT for training set disease-associated KCNQ1 variants (nd = not determined). Functional data from the literature are for V100I,27 Y111C,28 L114P,28 P117L,28 V207M,29 L236R,30 and A300T.31

Functional properties of KCNQ1 variants of unknown significance

We used this optimized approach to determine the functional properties of 48 additional KCNQ1 variants that have not been studied previously (Supplemental Table S5; Supplemental Fig. S4). Sixteen disease-associated variants were from the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD)22 and an additional 24 variants of unknown significance were provided in de-identified formats by two commercial genetic testing laboratories (GeneDx, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA; Transgenomic Inc., New Haven, CT, USA). The associated disease was LQTS for the majority of the variants. Eight additional rare variants were from the Exome Aggregation Database (ExAC).32 The majority of variants were within the voltage-sensing domain, which parallels our study of KCNQ1 variant structure restricted to this domain.33

Recordings were made from 12 separate transfection experiments (average transfection efficiencies were KCNQ1: 84 ± 6.7%, KCNE1: 79.4 ± 7.6% and co-transfection: 75 ± 7.9%; with viability of 94.9 ± 4.7%) and data from 2,566 cells were used for final analysis (12 384-well plates, average 46 cells per variant; n = 343 WT cells). Figure 6A illustrates a waterfall plot of average current density for each variant expressed as percent of WT. Averaged whole-cell current traces from each variant are presented in Supplemental Fig. S6. The majority of the disease-associated variants and two rare variants from ExAC exhibited severe loss-of-function (defined as < 25% of WT current density or > +20 mV shift in activation V½; see Supplemental Table S3). The remaining variants exhibited more modest differences in current density compared with WT channels with the exception of R109L, a rare ExAC variant that exhibited a profound gain-of-function (223% of WT). Two other ExAC variants (T104I, V215G) exhibited significantly lower current density than WT channels (22% and 35% of WT current, respectively) demonstrating that rare variants present in population databases can have functional effects.

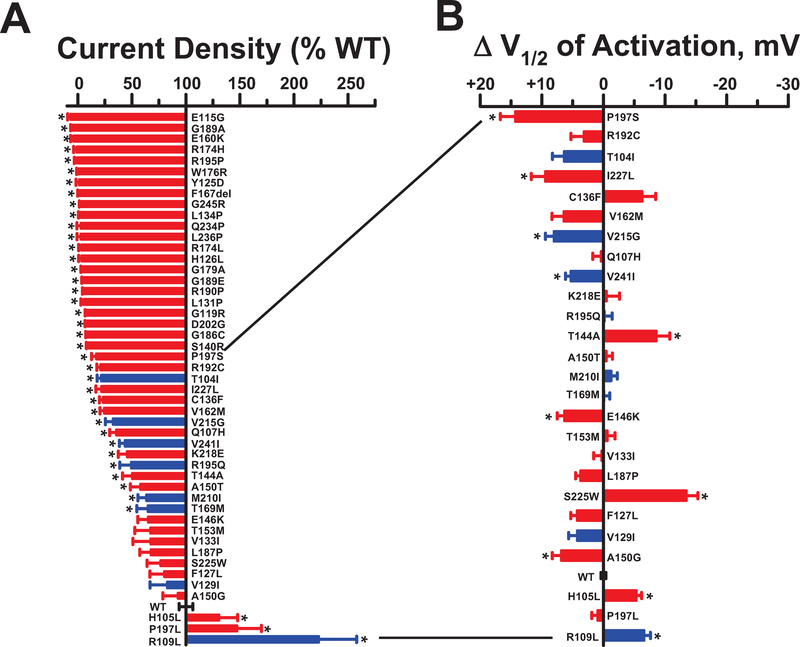

Figure 6: Functional properties of KCNQ1 variants of unknown significance.

A. Plot of average whole-cell current density (measured at +60 mV) recorded from cells expressing test KCNQ1 variants and displayed as percent of WT (n = 23–94). KCNQ1 variants are ordered from lowest to greatest current density with red bars indicating disease-associated variants and blue bars representing ExAC variants. B. Difference in activation V½ relative to WT determined for variants with current amplitude >10% of WT (n = 6–55). Variants are listed in the same order as in panel a. Bar height indicates mean value and error bars are SEM (* indicates p ≤ 0.01). Quantified functional parameters are provided in Supplemental Table S4c.

Some of the variants in the test set with preserved current density exhibited effects on the voltage-dependence of activation or had altered gating kinetics including slower (e.g., T144A and S225W) or faster (e.g., C136F and V244I) deactivation (Fig. 6b; Supplemental Fig. S7; Supplemental Table S4c) observed by both automated and manual patch clamp recording. Notable is the behavior of P197L, a rare variant originally described in a study of cost effectiveness of genetic testing for heritable cardiac disorders including LQTS,34 but also discovered incidentally in a breast cancer cohort undergoing exome sequencing.35 This variant exhibits a moderate gain-of-function (145% of WT current) that is inconsistent with a mutation causing LQTS. This finding highlights the value of experimental evidence for accurate variant classification.

Functional properties of heteromultimeric channels

Because most cases of LQTS are inherited as an autosomal dominant trait or arise from heterozygous de novo mutations, we assessed the functional consequences of KCNQ1 test set variants expressed together with the WT allele. These experiments were designed to identify dominant-negative behavior of channel variants. To insure equal levels of WT and variant KCNQ1 expressed together with KCNE1 and to avoid the need to perform unreliable triple plasmid co-transfections, we first created a CHO cell line stably expressing a single copy of KCNE1 inserted at a single genomic integration site (CHO-KCNE1 cells; see Methods). We then co-electroporated CHO-KCNE1 cells with equal mass amounts of separate plasmids encoding WT KCNQ1 (in tandem with the monomeric red fluorescent protein mScarlet) or variant KCNQ1 (coupled to expression of EGFP). Under optimized electroporation conditions, flow cytometry demonstrated equally high levels of expression of both plasmids (Supplemental Fig. S8a,b). The functional properties of IKs recorded from CHO-KCNE1 co-electroporated with WT KCNQ1-mScarlet and WT KCNQ1-EGFP were not different from cells transiently expressing one copy of WT KCNQ1 with KCNE1 (Supplemental Fig. S8c,d).

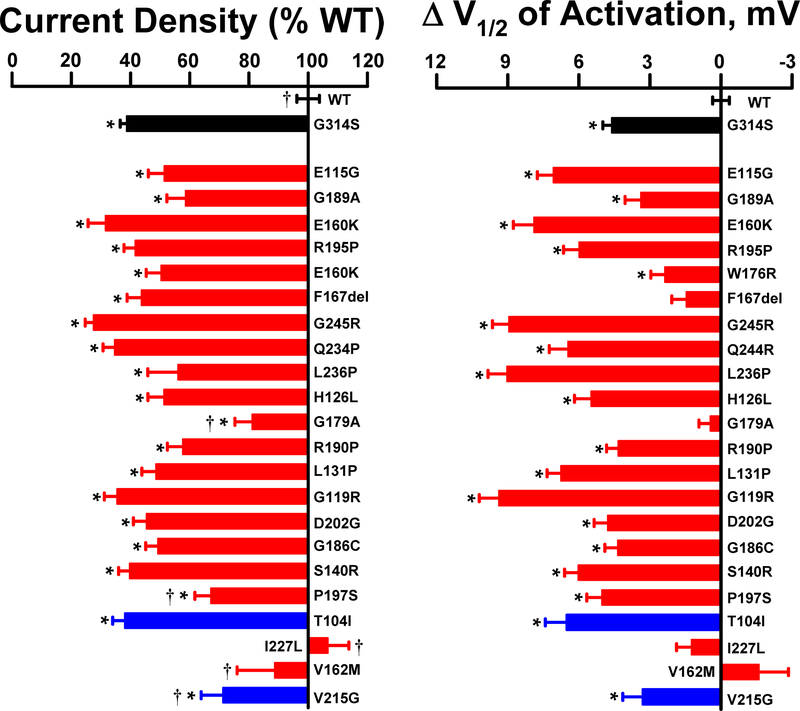

We determined the functional properties of 29 KCNQ1 variants expressed as WT/variant heteromultimeric channels. This group of variants exhibited complete or near complete loss-of-function when expressed as homomeric channels (Fig. 6) and were candidates for dominant-negative mutants. For comparison, we included a known dominant-negative mutant (G314S)36 co-expressed with WT KCNQ1, and cells transfected with two copies of WT KCNQ1 in the different vectors. We excluded 7 variants from analysis because expression levels were consistently different from WT (green:red fluorescence ratio <0.9 or >1.1) thereby confounding interpretation. Figure 7 illustrates the relative current density and activation V½ values for the 22 variants successfully co-expressed with WT KCNQ1, Supplemental Fig. S9 presents the averaged whole-cell current traces normalized for membrane capacitance, and quantitative values of functional properties are presented in Supplemental Table S4d. Most of the variants (17 of 22) exhibited current density levels that were not significantly different from the dominant-negative mutant. By contrast, the peak current densities of I227L and V162M were ‘rescued’ to levels that were not significantly different from cells co-expressing two copies of WT KCNQ1. These results demonstrate the capability of our platform to discern dominant-negative behavior of KCNQ1 variants.

Figure 7: Dominant-negative behavior of KCNQ1 variants.

A. Average whole-cell current density (measured at +60 mV) recorded from CHO-KCNE1 cells co-expressing WT KCNQ1 with select variants (n = 27–75). Values are expressed as percent of mean current density recorded from CHO-KCNE1 cells co-transfected with two different WT KCNQ1 plasmids (KCNQ1-mScarlet, KCNQ1-EGFP; n = 247). Red and blue bars represent disease-associated variants and population variants (ExAC), respectively. For comparison, current density recorded from cells co-expressing WT KCNQ1 with a known dominant-negative mutant (G314S; n = 206) is plotted (black bar). B. Difference in activation V½ relative to WT + WT determined for variants co-expressed with WT (n = 23–56). Bar height indicates mean value and error bars are SEM (* indicates p ≤ 0.01 for differences between variant + WT and WT + WT; † indicates p ≤ 0.01 for differences between variant + WT and G314S + WT). Quantified functional parameters are provided in Supplemental Table S4d.

Impact of functional evaluation on variant classification

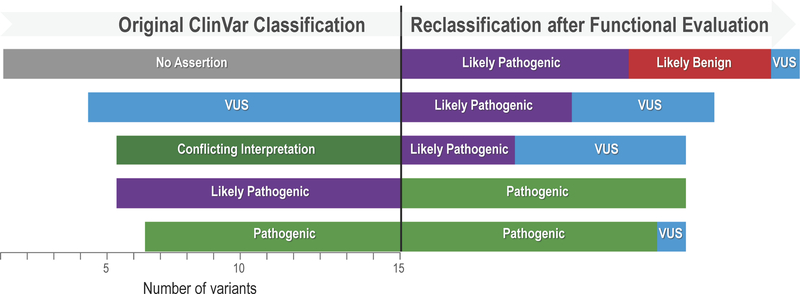

We assessed the potential impact of our functional data on the classification of KCNQ1 variants. Among the 78 variants investigated in this study, 56 were annotated in the ClinVar database with assertions regarding the likelihood of pathogenicity ranging from no assertion to pathogenic. Using a conservative approach, we reclassified those variants according to their functional phenotype. Variants with severe loss-of-function according to the criteria in Supplemental Table S3 were reclassified as ‘likely pathogenic’ when the original ClinVar classification was uninformative (e.g., VUS, conflicting interpretations, no assertion provided), or as ‘pathogenic’ if originally classified as ‘likely pathogenic’. Variants with normal or near normal functional properties were reclassified as ‘likely benign’ when there was no assertion of pathogenicity. Finally, variants with milder degrees of dysfunction were not reclassified reflecting uncertainty regarding pathogenicity.

Using this conservative reclassification strategy, 23 of 35 (66%) variants originally classified in uninformative categories could be reclassified as either ‘likely pathogenic’ or ‘likely benign’ (Fig. 8). Ten variants classified as ‘likely pathogenic’ in ClinVar could be reclassified as ‘pathogenic’ because of severe loss-of-function, whereas 9 other severe loss-of-function variants were already designated as ‘pathogenic’. Our analysis also demonstrated that 6 variants associated with LQTS (H105L, F127L, V129I, I132L, A150G, V207M) could be reclassified as ‘benign’ or ‘likely benign’ based on near normal channel function.

Figure 8: Reclassification of KCNQ1 variants.

The original classification in ClinVar is represented on the left half of the display and the reclassification based upon functional data is illustrated by the right half. The horizontal bars represent the variants classified in different categories and the length of the bars is proportional to the number of variants. One variant reclassified from Likely Benign to Benign is not illustrated.

DISCUSSION

Mutations in genes encoding ion channels are associated with a variety of monogenic disorders with diverse clinical manifestations that are collectively called channelopathies. The emergence of widespread clinical genetic testing and the use of next-generation sequencing in genetic research has resulted in explosive growth of known ion channel variants associated with disease traits and in populations. As with other genetic disorders for which genetic testing is routine, discriminating pathogenic from benign variants and establishing genotype-phenotype relationships has become increasingly more challenging.

A new and widely embraced scheme for variant classification proposed by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) is based on sets of weighted criteria that can be scored to assess the likelihood of pathogenicity.3 Among the criteria weighted as strongly supportive of classifying variants as pathogenic is the availability of data from in vitro or in vivo functional studies demonstrating a damaging effect on the gene or gene product (PS3 criterion).3 By contrast, in silico predictions of variant effects are considered supporting evidence, the least strong criterion. Our approach to high throughput functional evaluation of KCNQ1 variants offers a rich new data source that satisfies the PS3 criteria and can aid variant classification. Importantly, although our findings for many of the LQTS-associated variants are consistent with severe loss-of-function and consequent pathogenesis of the disease, our data are best viewed as informing about the functional properties of variants and not a judgement about pathogenicity. Final assertions about variant pathogenicity need also to consider phenotypic and genetic data. However, our conceptual experiment assessing the potential impact of functional data on variant classification (Fig. 8) suggests that a large proportion of variants with uninformative or no assertions of pathogenicity could be moved into more definitive categories with some caveats. There may be cases where functional studies in heterologous cells show normal channel activity, but undetected defects in post-translational modification or protein-protein interactions occurring exclusively in cardiomyocytes may promote pathogenicity. Hence, normal channel function alone may not suffice to down-classify a VUS to a benign category.

A major technological advance enabling modern studies of ion channels has been patch clamp electrophysiology, which underlies decades of important discoveries in several disciplines. For channelopathies, in vitro functional assessments of ion channel function using patch clamp recording has been the cornerstone of research determining the functional impact of mutations and establishing genotype-phenotype relationships. Although the patch clamp technique brought about a revolution in ion channel biology, the method in its typical embodiment has limited throughput and is extremely time and labor intensive. In an abstract sense, ion channel electrophysiology has advanced in a manner similar to that of DNA sequencing technology, although its democratization has lagged far behind sequencing. Originally, DNA sequencing was a difficult, low-throughput method performed only in elite genetics and molecular biology laboratories having specialized expertise and equipment.37 As methods became more standardized, more laboratories adopted DNA sequencing to perform small scale projects. Development of automated sequencing instruments enabled more widespread use and larger scale projects such as genome sequencing. Similarly, in the early days of patch clamp electrophysiology, methods were difficult and non-standardized with only a few laboratories having the necessary expertise and requisite equipment. Over time, standardization of hardware and software allowed more investigators to perform patch clamp recording for an expanding array of research applications. Newly developed automated patch clamp instruments have been implemented primarily for drug discovery, but these technologies are poised to enable wider applications including the large scale functional annotation of genetic variants in ion channel genes, as we demonstrated in this study.

In this study, we utilized automated patch clamp recording to enable a large scale functional analysis of KCNQ1 variants. To enable effective use of this technology, we first optimized a highly efficient method for transient transfection of heterologous cells using a high capacity electroporation platform. The unique combination of these two technologies provided a strategy with a much greater throughput than standard methods. We validated this approach by comparing results with manual patch clamp recording including published data from other laboratories. We elucidated the functional consequences of 48 variants of unknown significance in KCNQ1 and this represents ~45% increase in the number of variants with known function. Importantly, the bulk of the initial experimental work involved with studying the 48 KCNQ1 variants as homomeric channels was completed in approximately 12 weeks and additional parallelization of the workflow can further accelerate this timeline. Based on our current workflow efficiency, it should be feasible to generate and functionally evaluate a batch of 12 KCNQ1 variants within 2 weeks. In addition to demonstrating the functional effects of several KCNQ1 variants, which alone will likely contribute to classifying many variants, we also demonstrated the capability of our approach to identify dominant-negative behaviors among the disease-associated variants. Efficient, high-throughput experimental functional studies of ion channel variants can be harnessed to decrypt many more variants of unknown significance.

We did not assess the effects of β-adrenergic stimulation on KCNQ1 variant function. Previous studies have demonstrated that certain variants associated with LQTS may blunt IKs responses to adenylyl cyclase activation by forskolin, a proxy for activated β-adrenergic signaling.38,39 In the heterologous cell expression system we used (CHO-K1 cells), we were unable to demonstrate activation of IKs by forskolin (Supplemental Fig. S2b), presumably because these cells lack A-kinase anchor protein 9 (yotiao) required to phosphorylate the channel complex.40 Additionally, our study did not examine variants throughout the entire KCNQ1 protein in part because we wanted to concentrate on the voltage-sensing domain, which was the focus of a parallel investigation of KCNQ1 variant structure and trafficking.33 The technological approach we demonstrated in our present study will enable larger scale studies of variants throughout the full length KCNQ1 channel in the future.

In summary, we demonstrated the feasibility and robustness of a novel union of technologies (high efficiency cell electroporation, automated planar patch clamp recording) in a scalable platform for rapidly assessing the functional consequences of genetic variants in a human ion channel gene, KCNQ1. The workflow can be adapted for assaying variants in other ion channels and should also be suitable for pharmacological profiling of individual variants. Elucidating the function of human ion channel variants using this high throughput experimental approach can promote data-driven variant classification and create new opportunities for precision medicine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Dr. Tom Callis for providing KCNQ1 variant data from Transgenomic, Inc.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant HL122010 (A.L.G. and C.R.S.) and the Northwestern Medicine Catalyst Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References:

- 1.Eilbeck K, et al. Settling the score: variant prioritization and Mendelian disease. Nat Rev Genet 2017;18:599–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper GM, Shendure J. Needles in stacks of needles: finding disease-causal variants in a wealth of genomic data. Nat Rev Genet 2011;12:628–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manolio TA, et al. Bedside back to bench: Building bridges between basic and clinical genomic research. Cell 2017;169:6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ptacek LJ. Episodic disorders: channelopathies and beyond. Annu Rev Physiol 2015;77:475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster G, Berul CI. An update on channelopathies: from mechanisms to management. Circulation 2013;127:126–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George AL Jr . Molecular and genetic basis of sudden cardiac death. J Clin Invest 2013;123:75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz PJ, et al. Long-QT syndrome: from genetics to management. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5:868–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz PJ, et al. Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2009;120:1781–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz PJ, et al. Impact of genetics on the clinical management of channelopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: a transatlantic clinical approach to diagnosis and therapy. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3109–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapplinger JD, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of mutations from the first 2,500 consecutive unrelated patients referred for the FAMILION long QT syndrome genetic test. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanguinetti MC, et al. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac IKs potassium channel. Nature 1996;384:80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barhanin J, et al. KvLQT1 and IsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKs cardiac potassium current. Nature 1996;384:78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellocq C, et al. Mutation in the KCNQ1 gene leading to the short QT-interval syndrome. Circulation 2004;109:2394–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno C, et al. A new KCNQ1 mutation at the S5 segment that impairs its association with KCNE1 is responsible for short QT syndrome. Cardiovasc Res 2015;107:613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YH, et al. KCNQ1 gain-of-function mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. Science 2003;299:251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong K, et al. De novo KCNQ1 mutation responsible for atrial fibrillation and short QT syndrome in utero. Cardiovasc Res 2005;68:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnestad M, et al. Prevalence of long-QT syndrome gene variants in sudden infant death syndrome. Circulation 2007;115:361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes TE, et al. Cardiac potassium channel dysfunction in sudden infant death syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2007;44:571–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Postmortem long QT syndrome genetic testing for sudden unexplained death in the young. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenson PD, et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database: towards a comprehensive repository of inherited mutation data for medical research, genetic diagnosis and next-generation sequencing studies. Hum Genet 2017;136:665–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerche C, et al. Molecular impact of minK on the enantiospecific block of IKs by chromanols. Br J Pharmacol 2000;131:1503–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerlach U, et al. Synthesis and activity of novel and selective IKs-channel blockers. J Med Chem 2001;44:3831–3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li B, et al. Predicting the functional Impact of KCNQ1 variants of unknown significance. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2017;10:e001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartos DC, et al. The R231C mutation in KCNQ1 causes type 1 long QT syndrome and familial atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordeiro JM, et al. Overlapping LQT1 and LQT2 phenotype in a patient with long QT syndrome associated with loss-of-function variations in KCNQ1 and KCNH2. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2010;88:1181–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahimene S, et al. The N-terminal juxtamembranous domain of KCNQ1 is critical for channel surface expression: implications in the Romano-Ward LQT1 syndrome. Circ Res 2006;99:1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eldstrom J, et al. Mechanistic basis for LQT1 caused by S3 mutations in the KCNQ1 subunit of IKs. J Gen Physiol 2010;135:433–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steffensen AB, et al. High incidence of functional ion-channel abnormalities in a consecutive long QT cohort with novel missense genetic variants of unknown significance. Sci Rep 2015;5:10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianchi L, et al. Mechanisms of IKs suppression in LQT1 mutants. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000;279:H3003–H3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lek M, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, et al. Mechanisms of KCNQ1 channel dysfunction in long QT syndrome involving voltage sensor domain mutations. Sci Adv 2018;4:eaar2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabater-Molina M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of genetic studies in inherited heart diseases. Cardiogenetics 2013;3:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxwell KN, et al. Evaluation of ACMG-guideline-based variant classification of cancer susceptibility and non-cancer-associated genes in families affected by breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2016;98:801–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brink PA, et al. Phenotypic variability and unusual clinical severity of congenital long-QT syndrome in a founder population. Circulation 2005;112:2602–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shendure J, et al. DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future. Nature 2017;550:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heijman J, et al. Dominant-negative control of cAMP-dependent IKs upregulation in human long-QT syndrome type 1. Circ Res 2012;110:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barsheshet A, et al. Mutations in cytoplasmic loops of the KCNQ1 channel and the risk of life-threatening events: implications for mutation-specific response to beta-blocker therapy in type 1 long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2012;125:1988–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marx SO, et al. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science 2002;295:496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.