Abstract

Tuberculosis is one of the leading causes of morbidity worldwide and the incidences of drug resistance and intolerance are prevalent. Thus, there is a desperate need for the development of new anti-tubercular drugs. Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase inhibitors (MGIs) are napthyridone/aminopiperidine-based drugs that display activity against M. tuberculosis cells and tuberculosis in mouse models [Blanco, D., et al. (2015) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 1868-1875]. Genetic and mutagenesis studies suggest that gyrase, which is the target for fluoroquinolone antibacterials, is also the target for MGIs. However, little is known regarding the interaction of these drugs with the bacterial type II enzyme. Therefore, we examined the effects of two MGIs, GSK000 and GSK325, on M. tuberculosis gyrase. MGIs greatly enhanced DNA cleavage mediated by the bacterial enzyme. In contrast to fluoroquinolones (which induce primarily double-stranded breaks), MGIs induced only single-stranded DNA breaks under a variety of conditions. MGIs work by stabilizing covalent gyrase-cleaved DNA complexes and appear to suppress the ability of the enzyme to induce double-stranded breaks. The drugs displayed little activity against type II topoisomerases from several other bacterial species, suggesting that these drugs display specificity for M. tuberculosis gyrase. Furthermore, MGIs maintain activity against M. tuberuclosis gyrase that contained the three most common fluoroquinolone resistance mutations seen in the clinic, but displayed no activity against human topoisomerase IIα. These findings suggest that MGIs have potential as anti-tubercular drugs, especially in the case of fluoroquinolone-resistant disease.

Keywords: gyrase, Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase inhibitors, fluoroquinolones, tuberculosis, single-stranded DNA cleavage

Graphical Abstract

Tuberculosis is a lung infection caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an aerobic bacillus that stains neither Gram-positive nor Gram-negative.1 It is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide and recently surpassed HIV/AIDS as the deadliest disease caused by a single infectious agent.2 In 2016, there were an estimated 10.4 million new cases of tuberculosis reported world-wide and 1.7 million people died from the disease. Of these reported cases, an estimated 490,000 were diagnosed with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.3

The standard treatment regimen for tuberculosis includes rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol.1,4 However, fourth-generation fluoroquinolone antibacterials, such as moxifloxacin (Figure 1) and levofloxacin, are critical drugs for treating patients who have multidrug-resistant tuberculosis or are intolerant of first-line therapies.5 Unfortunately, fluoroquinolone resistance is on the rise and is starting to impact the treatment of tuberculosis.2 In most cases, this resistance is caused by mutations in gyrase, a type II topoisomerase, which is the cellular target for these drugs.6–12

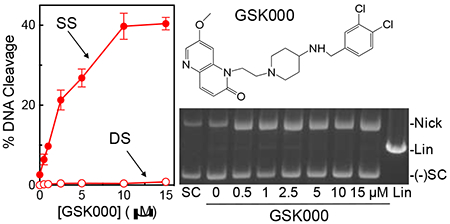

Figure 1.

Structures of selected compounds that alter the activity of gyrase. GSK000 and GSK325 are Mycobacterium tuberculosis Gyrase Inhibitors (MGIs); GSK 126 is a Novel Bacterial Topoisomerase Inhibitor (NBTI); and moxifloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibacterial.

Most bacteria encode two type II topoisomerases, gyrase and topoisomerase IV.7, 10, 12–16 These enzymes alleviate the torsional stress that accumulates in DNA ahead of replication forks and transcription complexes and remove knots and tangles from the genome, respectively.12–13, 15, 17–22 They perform these tasks by creating a transient double-stranded DNA break in one DNA segment, passing a second DNA segment through the break, and ligating the broken segment.7, 10, 15, 22 M. tuberculosis is unusual in that it encodes only gyrase, which carries out the cellular functions of both type II enzymes.23–25 Thus, it is an ideal antibacterial target for disrupting M. tuberculosis DNA replication and transcription. Fluoroquinolones act by stabilizing a covalent gyrase-cleaved DNA complex (cleavage complex) that is a requisite intermediate in the double-stranded DNA passage reaction of the enzyme.6–12 This stabilization generates double-stranded breaks in the bacterial chromosome, which induces the SOS response and can lead to eventual cell death.6–12

The lack of available drugs and the rising incidence of drug resistance and intolerance point to a need for the development of new antitubercular agents.2 Two approaches have been used to address this issue: the discovery of new antibacterial targets and the development of new drugs that act through validated targets, but do not succumb to current resistance patterns. Using this latter approach, a new class of naphthyridone/aminopiperidine-based drugs that target bacterial type II topoisomerases has been described. These drugs are known as “novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors” (NBTIs),26 one of which (GSK126)27 is shown in Figure 1. NBTIs differ from fluoroquinolones in three important respects. First, some members of this drug family do not enhance enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage (and therefore are not classified as gyrase “poisons”) and act strictly as catalytic inhibitors.12, 26, 28–30 Second, those NBTIs that do enhance DNA cleavage appear to stabilize primarily single-stranded (as opposed to double-stranded) DNA breaks generated by bacterial type II topoisomerases.12, 28, 30 Consistent with this observation, the crystal structure of a Staphylococcus aureus gyrase-DNA cleavage complex formed in the presence of the NBTI GSK299423 contains only one drug molecule (centrally located between the two scissile bonds), as compared to two (one at each scissile bond) for fluoroquinolones.26, 31 Third, NBTIs retain activity against cells that express clinically relevant mutations in gyrase or topoisomerase IV that are associated with fluoroquinolone resistance.26, 28–30 In addition, while an S83L mutation in Escherichia coli GyrA increased the IC50 of ciprofloxacin from 0.35 μM to 15 μM, the activity of the NBTI GSK299423 was not altered by this mutation (IC50 ≈ 0.10 μM).26 Unfortunately, little else has been published regarding the actions of NBTIs against bacterial type II topoisomerases.

NBTIs display relatively poor activity against M. tuberculosis gyrase.27 However, to develop NBTI-like drugs that act against tuberculosis, Blanco et al. used a high-throughput screen to identify a subclass of naphthyridone/aminopiperidine-containing compounds that displayed activity against M. tuberculosis cells in culture and the disease in mouse models.27 Due to structural and activity differences compared to NBTIs, compounds in this class are known as “Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase inhibitors” (MGIs). The MGIs are represented by GSK000 and GSK325 in Figure 1. On the basis of genetic/mutagenesis studies in M. tuberculosis cells, the authors suggested that gyrase was the primary physiological target of MGIs.27 However, DNA cleavage studies with purified M. tuberculosis gyrase have yet to be reported for any MGI.

Given the potential clinical impact of MGIs for the treatment of tuberculosis, it is critical to understand how they interact with and affect the activity of their target. Therefore, we characterized the mechanism of action of MGIs against purified M. tuberculosis gyrase. GSK000 and GSK325 were potent enhancers of gyrase-mediated DNA cleavage. In contrast to fluoroquinolones, the MGIs induced only single-stranded DNA breaks and suppressed the ability of gyrase to generate double-stranded breaks. Furthermore, they maintained activity against gyrase enzymes that harbored the three most common fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in tuberculosis and displayed no activity against human topoisomerase IIα. These findings provide critical mechanistic insight into the actions of MGIs against their cellular target and establish a framework for understanding their actions against tuberculosis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

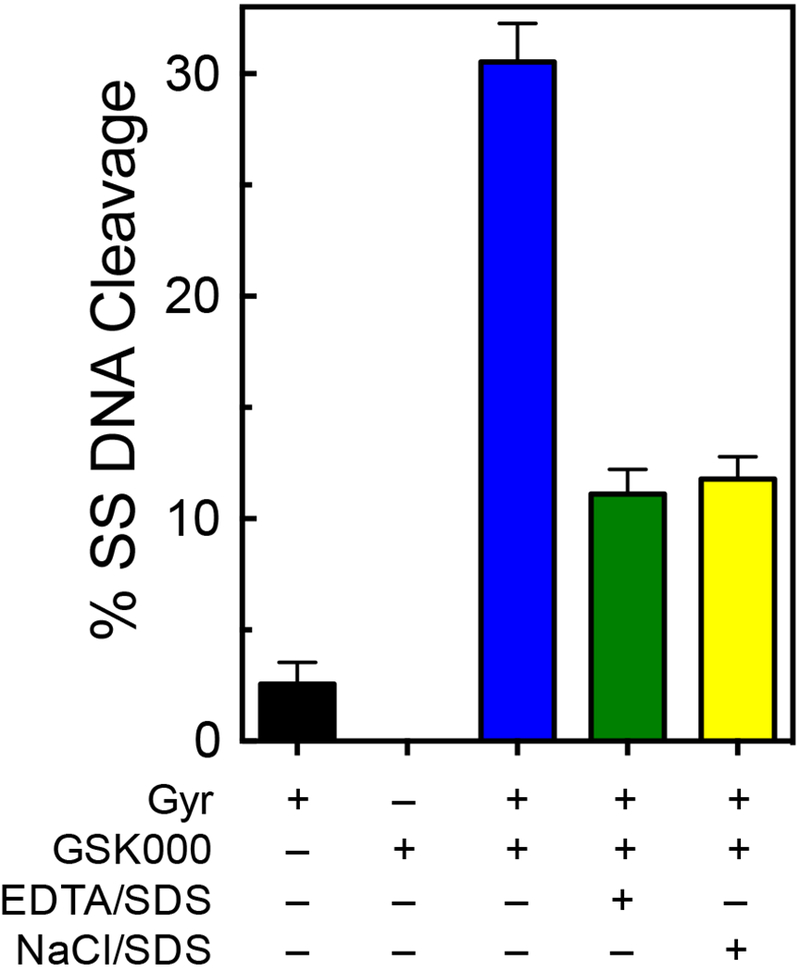

MGIs Induce Gyrase-mediated Single-stranded DNA Breaks.

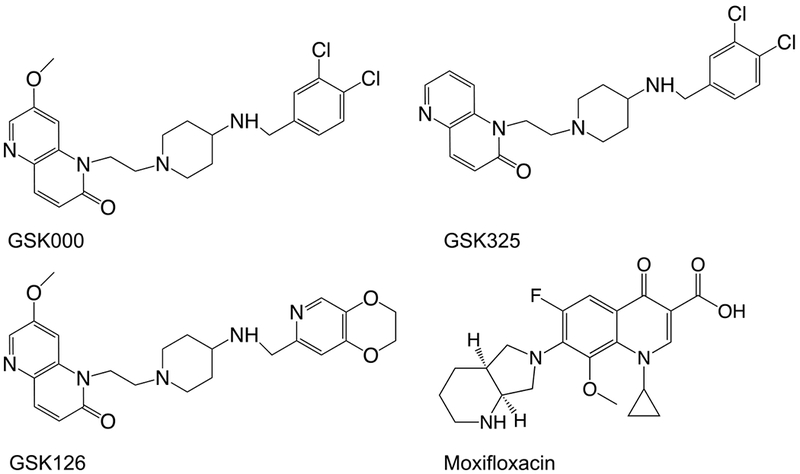

Despite the fact that MGIs appear to target gyrase in M. tuberculosis cells,27 their effects on the DNA cleavage activity of the enzyme have yet to be characterized in vitro. Therefore, the effects of GSK000 and GSK325 on the DNA cleavage activity of purified M. tuberculosis gyrase were determined and compared to those of the NBTI GSK126. As seen in Figure 2, all three of the compounds increased levels of single-stranded, but not double-stranded DNA breaks. This is in contrast to the effects of moxifloxacin on M. tuberculosis gyrase, which induces primarily double-stranded breaks (Figure 2, lower right gel). GSK000 was the most efficacious compound and increased levels of single-stranded DNA breaks ~21-fold (from 2% cleavage at baseline to 42% maximal cleavage in the presence of the compound) as compared to GSK325 (~12.5-fold enhancement, 25% maximal cleavage) and GSK126 (~7.5-fold enhancement, 15% maximal cleavage) (Figure 2, left panel). These data are consistent with the previous cellular studies, which reported that GSK000 was more cytotoxic than GSK325 and that the NBTI GSK126 had little effect on the growth of M. tuberculosis cells.27

Figure 2.

MGIs induce single-stranded DNA breaks mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase. The left panel shows the quantification of single-stranded (SS, closed circles) and double-stranded (DS, open circles) DNA breaks induced by GSK000 (red), GSK325 (blue), or GSK126 (black) in the presence of M. tuberculosis gyrase. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of four independent experiments. The top right gel shows DNA cleavage products produced by gyrase that was incubated with increasing concentrations of GSK000. The bottom right gel shows DNA products following cleavage reactions containing 10 μM GSK000 (000), GSK325 (325), or GSK126 (126), or 20 μM moxifloxacin (Moxi) in the presence of gyrase or 200 μM GSK000, GSK325, or GSK126 in the absence of enzyme. Negatively supercoiled (SC) and linear (Lin) DNA controls are shown along with a reaction that contained gyrase, but no drug (Gyr). The mobilities of negatively supercoiled DNA [(−)SC], nicked circular DNA (Nick), and linear DNA (Lin) are indicated. Gels are representative of at least four independent experiments.

As a control, all three compounds were incubated with a negatively supercoiled plasmid in the absence of gyrase. Even at a concentration of 200 μM (a concentration 20-fold higher than needed to induce maximal DNA scission in the presence of enzyme), no enhancement of double-stranded or single-stranded breaks was observed (Figure 2, lower right gel). Therefore, the DNA breaks observed in Figure 2 do not appear to be due to a chemical reaction between the MGIs/NBTI and DNA.

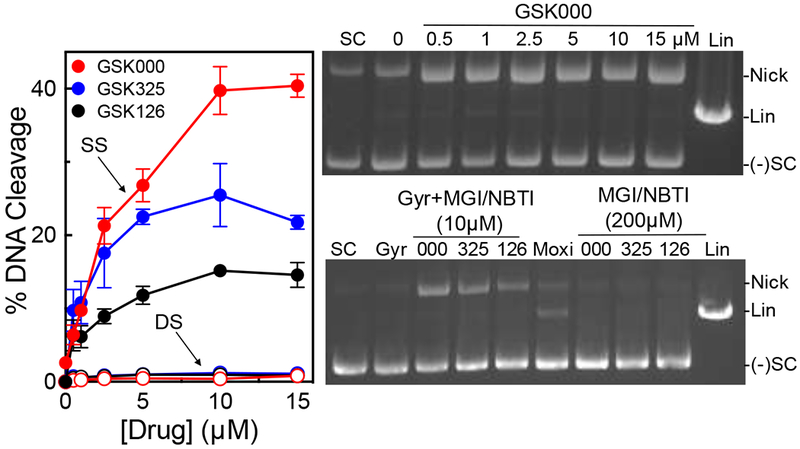

A number of experiments were carried out to further describe the enhancement of single-stranded DNA cleavage by MGIs. Because GSK000 was the most efficacious compound, it was used as the focus for these studies. First, when DNA cleavage reactions were stopped by the addition of EDTA (which reverses gyrase-mediated cleavage by chelating the active-site divalent metal ions) or NaCl (which reverses cleavage by disrupting enzyme-DNA binding) prior to the addition of SDS (which traps DNA cleavage complexes by denaturing the enzyme), levels of single-stranded breaks generated in the presence of GSK000 dropped precipitously (Figure 3). This finding confirms that DNA cleavage enhancement induced by the MGI was mediated by gyrase.

Figure 3.

DNA cleavage induced by GSK000 is mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase. The bar graph shows results from reactions that contained negatively supercoiled DNA in the presence of M. tuberculosis gyrase (Gyr, black bar), GSK000 (200 μM) in the absence of gyrase (GSK000), or complete reaction mixtures containing 10 μM GSK000 and gyrase that were stopped with SDS prior to the addition of EDTA (blue bar), and reactions that were treated with EDTA (green bar) or NaCl (yellow bar) prior to SDS. Error bars represent the SD of at least 4 independent experiments.

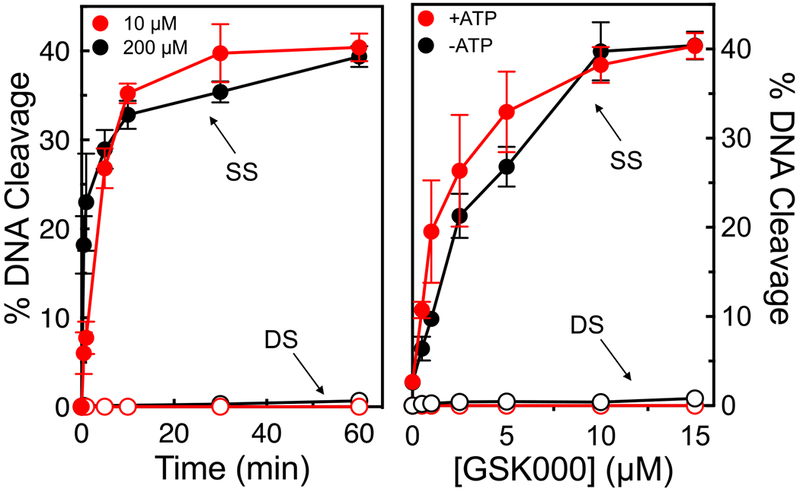

Second, some topoisomerase II poisons, such as the anti-cancer drug etoposide, generate primarily single-stranded breaks at low drug concentrations, but induce high levels of double-stranded breaks at high concentrations.32–33 Presumably, this reflects the difficulty of a second drug molecule entering the DNA-cleavage complex. Therefore, to determine whether MGIs can also be pushed to induce double-stranded DNA breaks at high concentrations, a 60-min time course for gyrase-mediated DNA cleavage was carried out at 10 and 200 μM GSK000 (Figure 4, left panel). Similar results were observed under both conditions. Even at 200 μM drug over a time course (60 min) that was 6 times longer than used for standard DNA cleavage assays, no generation of double-stranded breaks was observed. Thus, it appears that GSK000 induces only gyrase-mediated single-stranded cleavage.

Figure 4.

GSK000 enhances only single-stranded DNA breaks mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase. The panel on the left shows the enhancement of gyrase-mediated single-stranded (SS, closed circles) or double-stranded (DS, open circles) DNA breaks generated by gyrase over time in reactions that contained 10 μM (red) or 200 μM (black) GSK000. The right panel shows the effects of GSK000 on gyrase-mediated DNA cleavage in the presence (red) or absence (black) of ATP (1 mM). Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

Third, even though gyrase does not require ATP to mediate either DNA cleavage or ligation, it needs the high-energy co-factor to carry out its complete DNA strand passage reaction.7, 10 The DNA cleavage reactions shown in Figures 2–4 were carried out in the absence of ATP. Thus, to determine whether the high-energy co-factor influences the ability of MGIs to induce single- vs. double-stranded DNA breaks, a titration of GSK000 (0-15 μM) was carried out in the absence or presence of 1 mM ATP. As seen in Figure 4 (right panel), ATP had no effect on the levels of single-stranded DNA cleavage or the ability of gyrase to induce double-stranded breaks.

Taken together, the above findings provide strong evidence that MGIs induce only single-stranded DNA breaks mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase.

GSK000 Acts by Stabilizing Cleavage Complexes Formed by M. tuberculosis Gyrase.

Fluoroquinolone antibacterials increase levels of enzyme-mediated DNA strand breaks by stabilizing the covalent enzyme-DNA complexes that are formed upon scission of the genetic material.6–12, 31, 34 These drugs do so by intercalating into the DNA at each of the cleaved scissile bonds, blocking the ability of gyrase to rejoin the newly generated DNA ends.10, 12, 26, 35–37 However, only a single NBTI molecule (which is structurally related to the MGIs) appears to bind between the scissile bonds rather than intercalating within them and stretches the DNA.26–27 Consequently, it is not obvious how MGIs increase levels of gyrase-mediated DNA strand breaks. To this point, DNA lesions increase topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage by altering the structure of the genetic material within the cleavage site, allowing the enzyme to bend38 and cleave DNA faster.39–40 Therefore, two approaches were utilized to determine whether GSK000 alters the stability of cleavage complexes formed by M. tuberculosis gyrase. In both cases, the rate of loss of MGI-induced single-stranded DNA breaks was compared to the rate of loss of double-stranded breaks induced by the fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin.

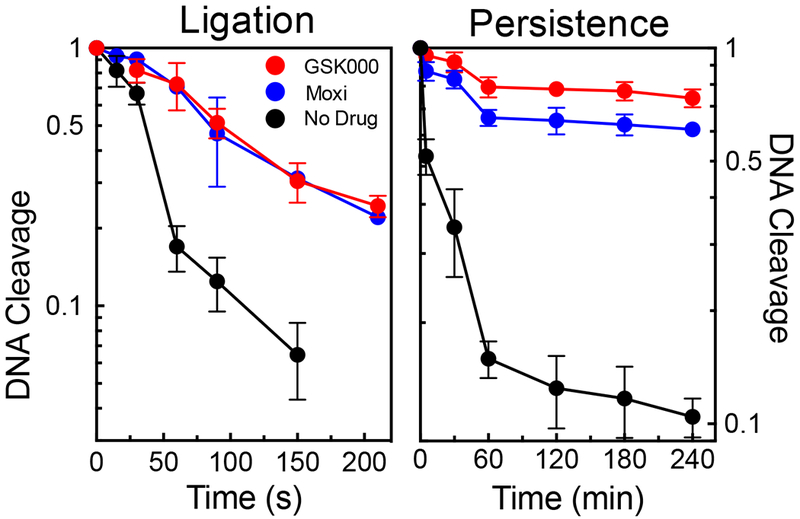

As a first approach, we monitored the effects of GSK000 on the rate of enzyme-mediated DNA ligation, which was determined by shifting cleavage complexes from 37 °C to 75 °C (a temperature that allows ligation, but not cleavage of the DNA). As seen in Figure 5 (left panel), the rate of gyrase-mediated DNA ligation in the presence of 10 μM GSK000 was ~3 times slower than observed in the absence of drug. This diminution in the rate of ligation is similar to that seen in the presence 50 μM moxifloxacin and suggests that GSK000 stabilizes cleavage complexes to a similar extent as the fluoroquinolone.

Figure 5.

Effects of GSK000 and moxifloxacin on ligation and persistence of cleavage complexes mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase. The rate of gyrase-mediated DNA ligation (left) and the stability of ternary gyrase–drug–DNA cleavage complexes (right) were monitored by the loss of single-stranded DNA breaks in the presence of 10 μM GSK000 (red) or the loss of double-stranded DNA cleavage in the absence of drug (black) or in the presence of 50 μM moxifloxacin (blue). Levels of DNA cleavage at time 0 (42% single-stranded breaks in the presence of GSK000 and 36% double-stranded breaks in the presence of moxifloxacin) were set to 1 to allow direct comparison. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

For the second approach, we monitored the effects of GSK000 on the persistence (stability) of cleavage complexes following a 20-fold dilution of reaction mixtures. This assay is believed to reflect the rate at which the drug dissociates from the ternary complex, given that enzyme-DNA-drug ternary complexes are much less likely to form when they are diluted. As seen in Figure 5 (right panel), GSK000 increased the lifetime of cleavage complexes to an extent even greater than that seen with moxifloxacin.

Thus, it appears that GSK000 increases the level of gyrase-mediated single-stranded DNA breaks primarily by increasing the stability of cleavage complexes.

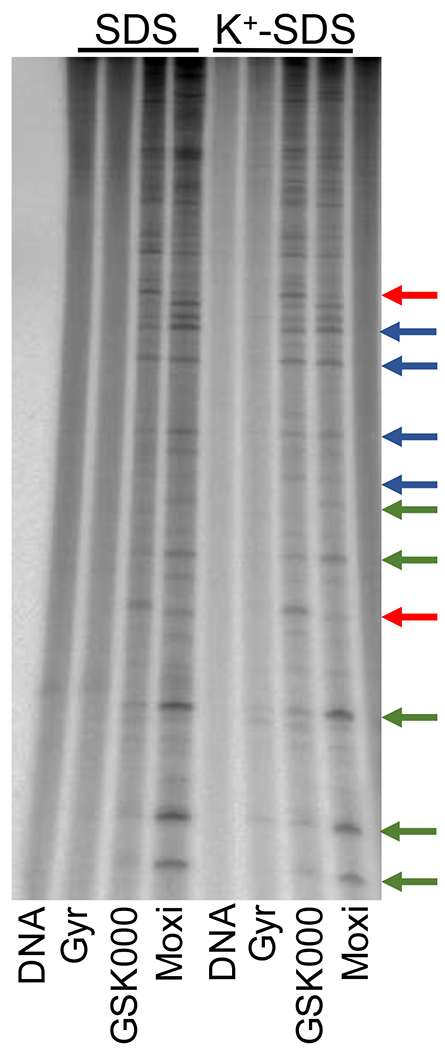

GSK000 and Moxifloxacin Induce Gyrase-mediated DNA Cleavage at a Different Array of Sites.

Sites of gyrase-mediated DNA scission were mapped in the presence of GSK000 or moxifloxacin to determine whether MGIs and fluoroquinolones display the same cleavage specificity (Figure 6). Linear end-labeled pBR322 was used for this experiment. Although overlap between the cleavage patterns generated by the MGI and the fluoroquinolone was observed (sites of similar cleavage are indicated by blue arrows), a number of unique sites or sites where utilization differed between the two drugs were observed. Representative sites that were cleaved more frequently in the presence of the MGI (red arrows) or the fluoroquinolone (green arrows) are indicated. These differences likely reflect the difference in the way MGIs and fluoroquinolones interact with M. tuberculosis gyrase.

Figure 6.

Effects of GSK000 and moxifloxacin on the sites of DNA cleavage generated by M. tuberculosis gyrase. An autoradiogram of a polyacrylamide gel is shown. Reaction mixtures contained DNA with no enzyme (DNA), enzyme in the absence of drug (Gyr), or enzyme in the presence of 100 μM GSK000 (GSK000) or 100 μM moxifloxacin (Moxi). The left- and right-hand sides of the gel show reactions processed without or following K+-SDS precipitation of DNA cleavage complexes. Red arrows indicate representative strong sites where GSK000 induced greater levels of DNA cleavage than did moxifloxacin, green arrows indicate representative strong sites where moxifloxacin induced greater levels of cleavage than did GSK000, and blue arrows indicate representative sites where GSK000 and moxifloxacin induced similar levels of cleavage. The autoradiogram is representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

Similar DNA cleavage results were obtained when cleavage complexes were enriched by K+-SDS precipitation of the gyrase prior to treatment with Proteinase K and electrophoresis (Figure 6). This provides further evidence that the cleavage observed was mediated by gyrase.

GSK000 Suppresses Double-stranded DNA Breaks Generated by M. tuberculosis Gyrase.

Previous studies have demonstrated that topoisomerase II poisons like etoposide are able to act independently at each scissile bond.32 Consequently, drug action on the Watson strand often has relatively little effect on levels of cleavage or rates of ligation on the Crick strand.32 Because MGIs/NBTIs do not appear to interact with the individual scissile bonds on the Watson and Crick strands, it is not obvious whether their presence coordinately affects cleavage on both strands. Thus, these compounds may enhance cleavage on only one strand of the double helix without affecting the other. Alternatively, the propensity of MGIs to induce single-stranded breaks suggests that they may suppress the ability of the enzyme to cut both strands of the double-helix.

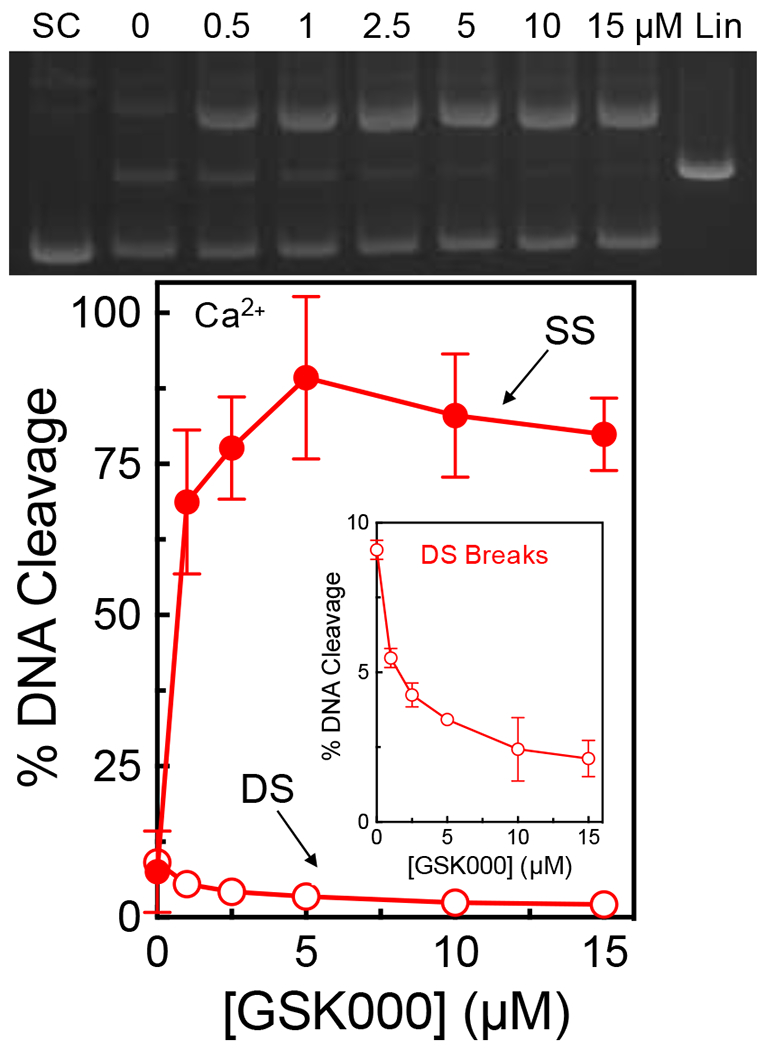

The low level of double-stranded DNA breaks induced by M. tuberculosis gyrase in the absence of drugs makes it difficult to differentiate between these two possibilities. Therefore, MgCl2 in DNA cleavage reactions was replaced with CaCl2. This latter divalent metal ion can replace Mg2+ in the active site of type II topoisomerases.41 Although most properties of the DNA cleavage and ligation reactions remain unchanged, considerably higher levels of enzyme-mediated double-stranded breaks are generated in the presence of Ca2+.31, 41 In the case of M. tuberculosis gyrase, background levels of enzyme-mediated double-stranded DNA cleavage increased to ~10% (from 2% in Mg2+).

As seen in Figure 7, GSK000 induced high levels of single-stranded DNA breaks in the presence of Ca2+. However, this enhancement of single-stranded DNA cleavage was accompanied by a decrease in double-stranded DNA-cleavage (a representative gel is shown at the top, with quantification shown in the bottom panel). This finding strongly suggests that the induction of cleavage by one MGI molecule actually suppresses cleavage of the second strand. The molecular basis for this property is not known. However, it likely results from a distortion of the DNA in the active site of the enzyme, similar to what is generated in the presence of NBTIs.26

Figure 7.

GSK000 suppresses double-stranded DNA breaks generated by M. tuberculosis gyrase. The gel (top) shows DNA cleavage products following incubation of gyrase with increasing concentrations of GSK000 in the presence of Ca2+. Negatively supercoiled (SC) and linear controls (Lin) are shown. The gel is representative of at least 4 independent experiments. The graph quantifies the effects of GSK000 on M. tuberculosis gyrase-mediated single-stranded (SS, closed circles) and double-stranded (DS, open circles) DNA cleavage. Error bars represent the SD of at least 4 independent experiments.

The Actions of GSK000 and Moxifloxacin on the Induction of Cleavage by M. tuberculosis Gyrase Are Mutually Exclusive.

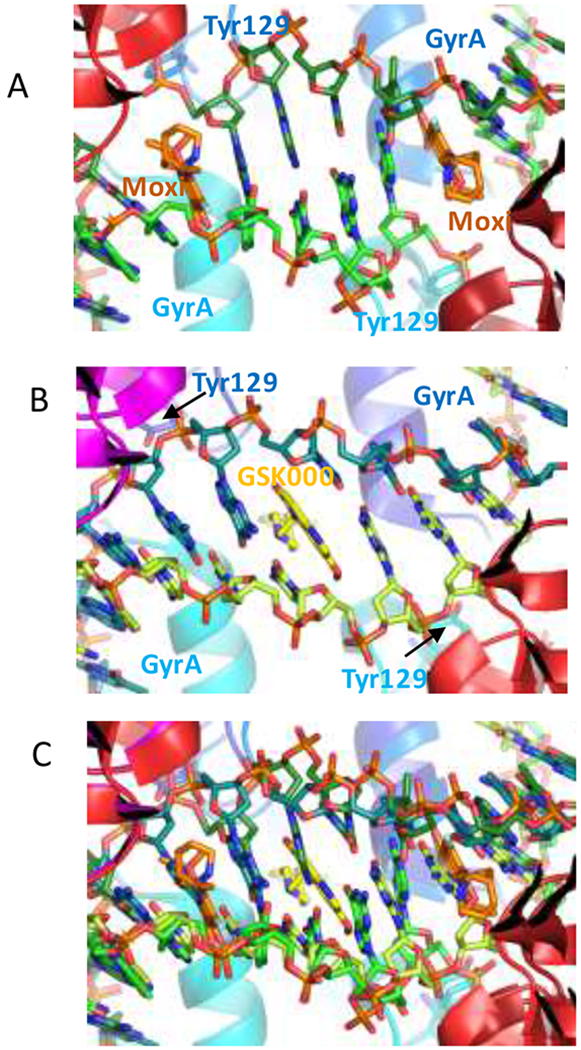

Because of the mechanistic and structural differences between the MGIs and fluoroquinolones, it is not known whether they can simultaneously affect DNA cleavage activity of a single gyrase enzyme. As a first step toward addressing this issue, modeling studies were carried out to address whether it is theoretically possible to form ternary gyrase-DNA-drug structures that include both GSK000 and moxifloxacin (Figure 8). On the basis of these studies, it does not seem possible for both drugs to interact simultaneously in the same ternary complex. NBTIs are believed to trap the enzyme in the CRsym conformation, in which only one compound can be accommodated within the DNA. In the model of the GSK000 complex (Figure 8B), which is in the CRsym conformation, the DNA is well ordered and there is no room at either cleavage site to accommodate an additional compound.42 The moxifloxacin structure (Figure 8A) is in an intermediate conformation in which the subunits have moved slightly apart allowing a second compound to be accommodated in the DNA.42 Note that the superimposition of the GSK000 and moxifloxacin structures (Figure 8C) requires that basepairs overlap with the compounds.

Figure 8.

Modeling studies suggest that moxifloxacin and GSK000 cannot interact simultaneously in the same drug-enzyme-DNA ternary complex. A. View down the two-fold axis of a crystal structure of a ternary complex formed with M. tuberculosis gyrase, DNA, and moxifloxacin.35 Gyrase subunits are shown in cartoon representation, in blue/cyan (GyrA) or red/dark red (GyrB). The catalytic tyrosine (Tyr 129) which has cleaved the DNA is shown in stick representation. Moxifloxacin (orange carbons) and DNA (green carbons) are also shown in stick representation. B. Model of a complex of GSK000 (yellow carbons) with M. tuberculosis gyrase and uncleaved DNA that was based on the crystal structure of GSK299423 with Staphylococcus aureus gyrase.26 C. Superimposition of A and B require that base-pairs overlap with the compounds.

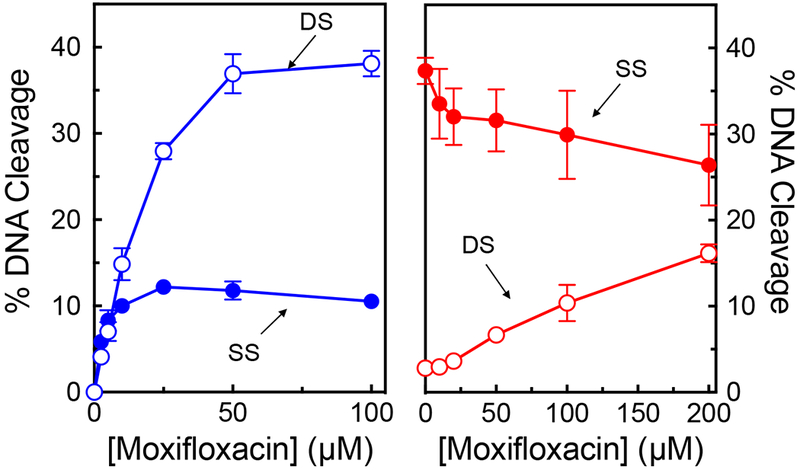

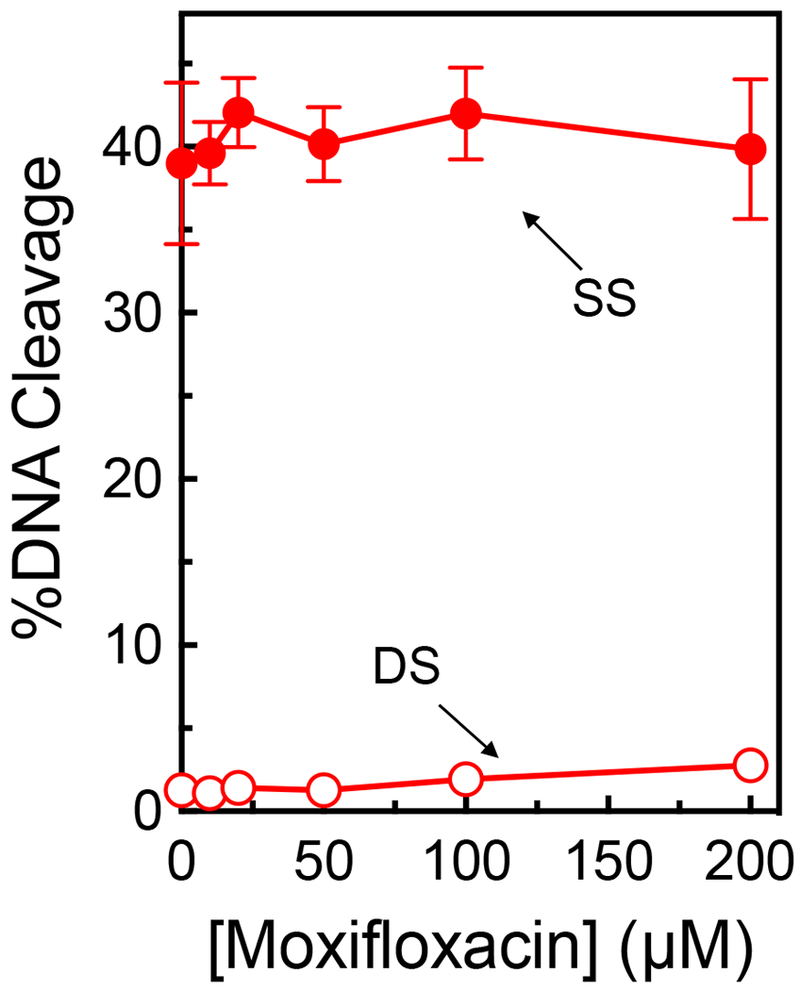

To confirm the conclusions of the modeling studies, a competition study was utilized to determine whether GSK000 and moxifloxacin are capable of acting within the same ternary complex. In the absence of the MGI, moxifloxacin readily induced enzyme-mediated double-stranded DNA breaks (~36% in the presence of 100 μM drug), but also induced ~12% single-stranded breaks (peaking at 25 μM) (Figure 9, left panel). In the competition study, M. tuberculosis gyrase was saturated with 10 μM GSK000 (yielding the typical ~40% single-stranded DNA breaks) (Figure 9, right panel) followed by incubation with 0-200 μM moxifloxacin. Changes in the level of double- and single-stranded breaks were monitored (Figure 9, right panel) to determine if there was competition or additivity between the two compounds. As the concentration of moxifloxacin increased, levels of double-stranded breaks rose, albeit to a lesser extent than seen in the absence of the MGI (similar changes in DNA cleavage were observed if gyrase was incubated with moxifloxacin prior to the addition of GSK000). Because GSK000 does not generate double-stranded DNA breaks, this increase demonstrates that the fluoroquinolone was able to stabilize cleavage complexes in reaction mixtures that also contain the MGI. However, it does not differentiate whether the GSK000 in reaction mixtures was replaced by moxifloxacin or was still situated within the ternary complex.

Figure 9.

The actions of GSK000 and moxifloxacin on gyrase-mediated DNA cleavage are mutually exclusive. In the left panel, enhancement of M. tuberculosis gyrase-mediated single-stranded (SS, closed circles) and double-stranded (DS, open circles) DNA cleavage is shown in the presence of moxifloxacin alone (blue). In the right panel, gyrase was saturated with 10 μM GSK000 followed by a subsequent titration of 0–200 μM moxifloxacin. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

To distinguish between these latter possibilities, we monitored the single-stranded breaks that are generated in the presence of both drugs (Figure 9, right panel). In contrast to double-stranded breaks, single-stranded breaks decreased in the presence of moxifloxacin. This finding suggests that moxifloxacin acts only when it can displace GSK000 from the complex. Had both drugs been present in the ternary complex, levels of single-stranded breaks would have been expected to rise, because both drugs induce enzyme-mediated single-stranded DNA cleavage. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the actions of MGIs and fluoroquinolones utilize mutually exclusive mechanisms to induce M. tuberculosis gyrase-mediated DNA cleavage.

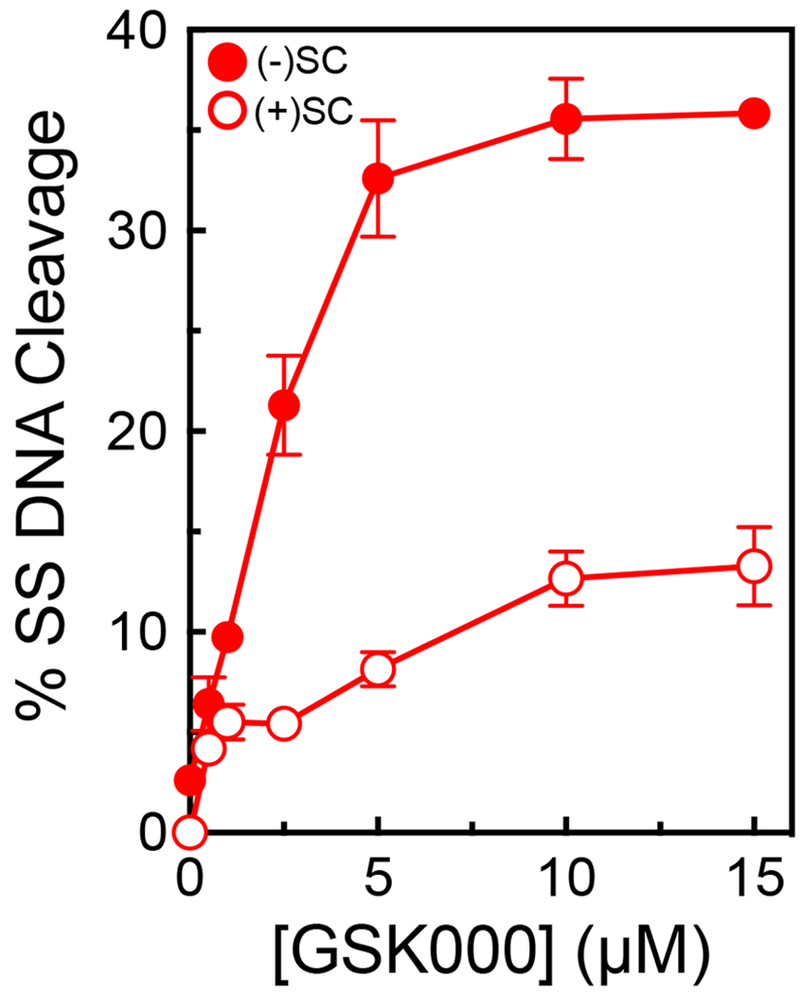

GSK000 Induces Lower Levels of Gyrase-mediated DNA Cleavage on Positively Supercoiled DNA.

In the cell, gyrase removes the positive supercoils that accumulate ahead of replication forks and transcription complexes.13, 18, 22 As these DNA tracking systems encounter the acting gyrase, transient cleavage complexes can be converted to non-ligatable DNA strand breaks that induce the SOS DNA damage response pathway.43 When this pathway is overwhelmed, the DNA breaks can lead to cell death. Because drug-stabilized cleavage complexes formed ahead of moving forks and transcription complexes are most likely to be converted to non-ligatable strand breaks, cleavage complexes stabilized on positively supercoiled DNA are the most dangerous for the cell.44–47 A recent study by Ashley et al. demonstrated that M. tuberculosis gyrase maintains 2-3-fold lower levels of cleavage complexes on positively compared to negatively supercoiled DNA in the absence or presence of fluoroquinolones.48 This attribute makes gyrase a safer enzyme (for cells) to work ahead of DNA tracking systems, but may also affect the cytotoxicity of fluoroquinolones.

Because MGIs/NBTIs interact differently with DNA within the cleavage complex than do fluoroquinolones, we wanted to determine whether GSK000 differentially affected DNA scission mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase on negatively and positively supercoiled substrates. As seen in Figure 10, gyrase induced ~3-4-fold lower levels of single-stranded breaks with positively supercoiled DNA. Thus, the effects of DNA supercoil geometry on the actions of MGIs and fluoroquinolones appear to be similar.

Figure 10.

GSK000 maintains lower levels of gyrase-mediated single-stranded DNA breaks on positively supercoiled DNA. The effects of GSK000 on the enhancement of gyrase-mediated single-stranded cleavage of negatively (closed circles) and positively (open circles) supercoiled DNA is shown. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

Effects of GSK000 on the Catalytic Activities of M. tuberculosis Gyrase.

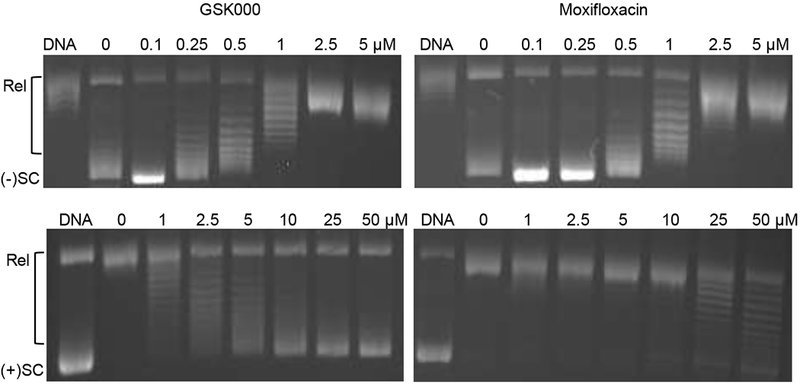

Some NBTIs appear to act by inhibiting the catalytic activities of bacterial type II topoisomerases rather than by poisoning these enzymes.12, 26, 28–30 In addition, the MGIs have been shown to inhibit the DNA supercoiling reaction catalyzed by M. tuberculosis gyrase.27 Therefore, the effects of GSK000 on the catalytic activities of M. tuberculosis gyrase were assessed and compared to those of moxifloxacin.

As seen in Figure 11 (top left and right panels), the IC50 values (~0.5 vs. 1 μM, respectively) for the inhibition of gyrase-catalyzed supercoiling of relaxed DNA by GSK000 and moxifloxacin were similar. This is in contrast to their abilities to kill M. tuberculosis cells27 or enhance DNA cleavage mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase (see Figures 2 and 9). In these latter two cases, GSK000 is ≥10-fold more potent than moxifloxacin. These data strongly suggest that the mechanism of cell killing by these two drugs is not directly associated with their ability to inhibit DNA supercoiling catalyzed by M. tuberculosis gyrase.

Figure 11.

Inhibition of gyrase catalyzed reactions by GSK000 and moxifloxacin. The effects of GSK000 (left panels) and moxifloxacin (right panels) on the supercoiling of relaxed DNA (top panels) and the relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA (bottom panels) are shown. The positions of relaxed (Rel), negatively supercoiled [(−)SC], and positively supercoiled [(+)SC] DNA are indicated. Gels are representative of at least four independent experiments.

In contrast to drug effects on DNA supercoiling, GSK000 was a more potent inhibitor of the gyrase-catalyzed relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA than was moxifloxacin (Figure 11, bottom left and right panels). The IC50 of the MGI (~2.5 to 5 μM) was at least an order of magnitude lower than that seen with moxifloxacin. The removal of positive DNA supercoils generated by replication forks represents a critical step in the elongation of DNA replication. Therefore, these results cannot rule out a role for the inhibition of gyrase-catalyzed removal of positive supercoils (in addition to their effects on gyrase-mediated DNA cleavage) in cell death induced by MGIs.

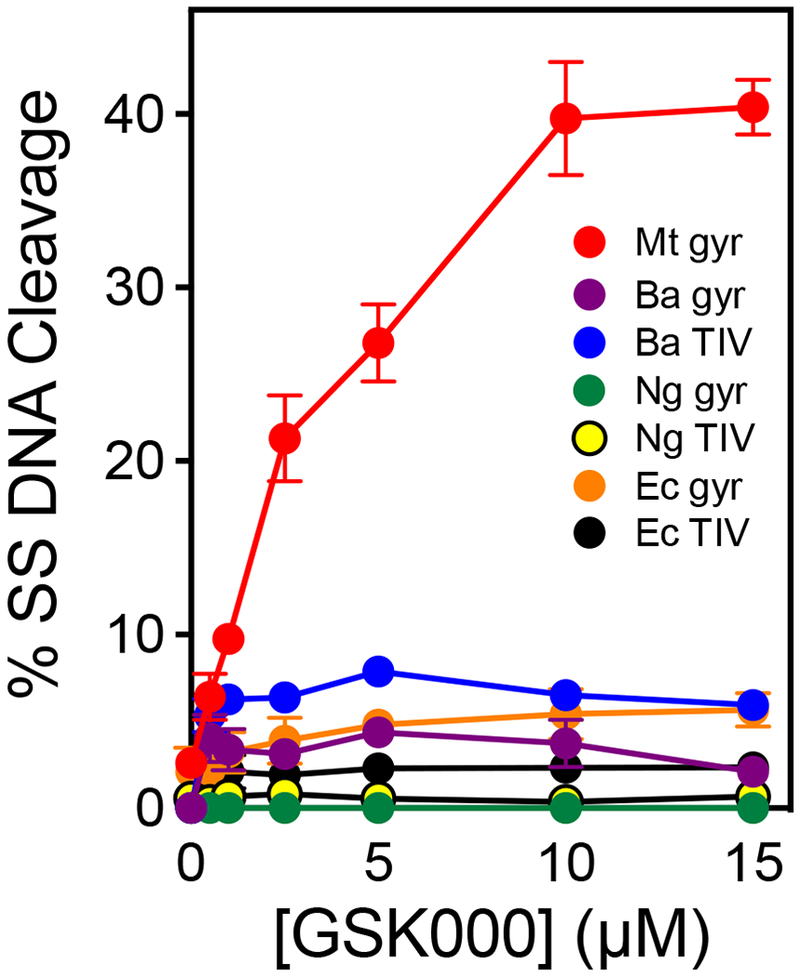

GSK000 Preferentially Acts Against M. tuberculosis Gyrase.

MGIs were originally selected for their ability to kill M. tuberculosis cells.27 However, it is not known whether the activity of MGIs toward this species reflects a broadened spectrum of drug activity or an increased specificity for M. tuberculosis. Therefore, the ability of GSK000 to induce DNA cleavage mediated by gyrase and topoisomerase IV from Gram-negative E. coli and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Gram-positive Bacillus anthracis was assessed (Figure 12). GSK000 displayed much lower activity against enzymes from these other species than it did for M. tuberculosis gyrase. Therefore, at least in regard to the interaction of MGIs with their enzyme target, it appears that the structural differences between MGIs and NBTIs increase the specificity of these drugs for M. tuberculosis gyrase rather than broadening their spectrum of action.

Figure 12.

GSK000 acts preferentially against M. tuberculosis gyrase. The effects of GSK000 on single-stranded DNA cleavage mediated by M. tuberculosis gyrase (Mt gyr, red), B. anthracis gyrase (Ba gyr, purple) and topoisomerase IV (Ba TIV, blue), N. gonorrhoeae gyrase (Ng gyr, green) and topoisomerase IV (Ng TIV, yellow), and E. coli gyrase (Ec gyr, orange) and topoisomerase IV (Ec TIV, black) are shown. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

In order to extend this conclusion from biochemical studies to the organismal level, it will be necessary to carry out extensive microbiological studies on a variety of bacterial species. However, a comparison of the activity of GSK000, GSK325, and GSK126 toward cultured M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) and E. coli (7623) cells is consistent with an enhanced specificity of MGIs toward M. tuberculosis. Whereas, the reported MIC values of GSK000 and GSK325 for M. tuberculosis were <0.01 μM and 0.08 μM, respectively, the MIC for the NBTI GSK126 was considerably higher (0.5 μM).27 In contrast, for E. coli, the MIC of GSK126 (0.26 μM) was substantially lower than those of the two MGIs GSK000 and GSK325 (2.2 μM and 2.3 μM, respectively). It is also notable that the MICs for GSK000 and GSK325 against E. coli are considerably higher than those reported with M. tuberculosis.

If the biochemical and microbiological data described above are representative of other species, an enhanced specificity of MGIs could have advantages for its clinical use. Tuberculosis is sometimes misdiagnosed as pneumonia, which is treated with fluoroquinolones.49–50 Unfortunately, this initial treatment is associated with the development of fluoroquinolone-resistant M. tuberculosis.50–53 If MGIs display specificity for M. tuberculosis, they would not be used to treat a misdiagnosed patient, potentially leading to fewer cases of resistance. In addition, anti-tuberculosis regimens are normally prescribed for several months.4–5 Thus, patients taking MGIs are potentially less likely to incur the adverse drug events associated with the long-term use of a broad-spectrum antibacterial in the regimen.1

MGIs share two properties with fluoroquinolones that may ultimately affect their clinical development. First, the MGIs inhibition of the hERG potassium channel may need to be decreased.27 Second, the reported frequency of spontaneous resistance mutations for GSK126 (no data is available for the MGIs) is higher than that of moxifloxacin.27 However, this value is similar to or lower than other drugs routinely used to treat tuberculosis.

MGIs Maintain Activity Against M. tuberculosis Gyrase Enzymes Carrying the Most Common Mutations Associated with Fluoroquinolone Resistance.

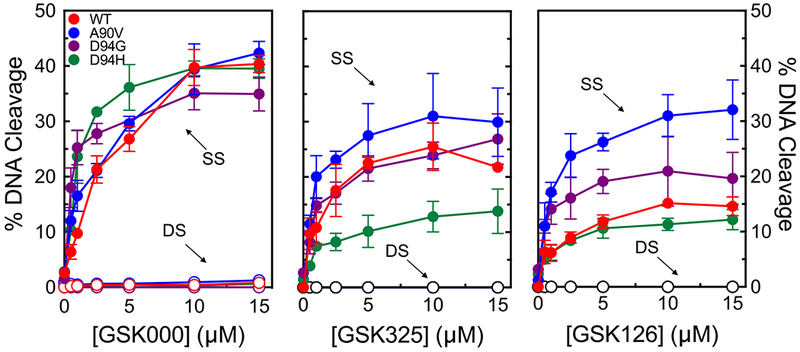

In a previous study, GSK000 and GSK325 maintained cytotoxic activity against M. tuberculosis cells that carried gyrase mutations GyrAA90V or GyrAD94G, both of which elicit fluoroquinolone resistance.27 However, the effects of these two MGIs on the DNA cleavage activity of M. tuberculosis gyrase enzymes that harbor these fluoroquinolone resistance mutations are unknown. Therefore, the effects of GSK000 and GSK325, as well as GSK126, on gyrase enzymes containing the GyrAA90V or GyrAD94G mutations or a GyrAD94H mutation were determined. These three gyrase alterations represent the most common mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in tuberculosis.9

As seen in Figure 13, all three of the compounds retained the ability to induce the mutant gyrase enzymes to generate single-stranded DNA breaks. GSK000 retained full activity against all three mutant enzymes (left panel). Although the activity of GSK325 (middle panel) was slightly lower when incubated with GyrAD94H, the compound maintained full activity against GyrAA90V and GyrAD94G. If anything, GSK126 (right panel) displayed higher activity against GyrAA90V and GyrAD94G. These results demonstrate that MGIs and a related NBTI are able to overcome the most common causes of target-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance in tuberculosis.

Figure 13.

MGIs/NBTI maintain activity against M. tuberculosis gyrase containing the most common mutations associated with clinical fluoroquinolone resistance. Effects of the MGIs GSK000 (left panel), GSK325 (middle panel), and the NBTI GSK126 (right panel) on wild-type (red) M. tuberculosis gyrase and gyrase containing the fluoroquinolone resistance mutations at GyrAA90V (blue), GyrAD94G (purple), or GyrAD94H (green) are shown. Single-stranded (SS) and double-stranded (DS) DNA breaks are denoted by closed and open circles respectively. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

We took advantage of these findings with the fluoroquinolone-resistant mutant enzymes to reexamine the moxifloxacin-GSK000 competition studies (Figure 9). In contrast to results with the wild-type enzyme, moxifloxacin was unable to compete with the actions of GSK000 against GyrAD94G (Figure 14). Even at 200 μM moxifloxacin, virtually no decrease in single-stranded breaks or increase in double-stranded breaks was observed. This finding confirms that the competition between moxifloxacin and GSK000 seen in Figure 9 was due to the replacement of the MGI by the fluoroquinolone in the active site of gyrase.

Figure 14.

The actions of GSK000 and moxifloxacin on DNA cleavage mediated by GyrAD94G. The mutant fluoroquinolone-resistant gyrase was saturated with 10 μM GSK000 followed by a subsequent titration of 0–200 μM moxifloxacin. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

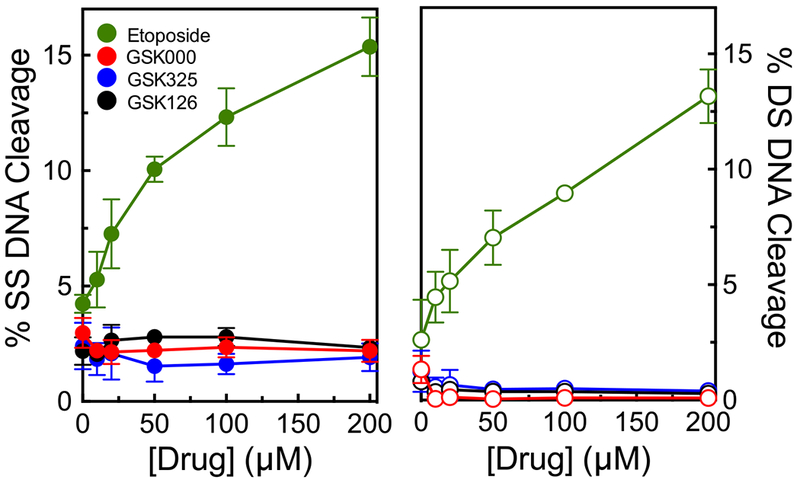

MGIs Do Not Induce DNA Cleavage Mediated by Human Topoisomerase IIα.

Bacterial and human type II topoisomerases share a significant level of amino acid identity.15 Although clinically relevant fluoroquinolone antibacterials display low activity against the human type II enzymes, some members of this drug class cross over into mammalian systems and are potent poisons of human type II topoisomerases.7, 10, 54–56 Because poisoning the human enzyme precludes the clinical use of these fluoroquinolones as antibacterial agents, it is important to assess the activity of gyrase-targeted drugs against the human enzymes.

The ability of GSK000 and GSK325, as well as the NBTI GSK126, to induce DNA strand breaks mediated by topoisomerase IIα is shown in Figure 15. None of the drugs displayed any effect on DNA cleavage mediated by the human enzyme. This result is in marked contrast to the high levels of single- and double-stranded breaks induced by etoposide, a clinically important anti-cancer drug.32, 57

Figure 15.

MGIs/NBTI do not enhance DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα. The left and right panels show the effects of the MGIs GSK000 (red) and GSK325 (blue) and the NBTI GSK126 (black) on single-stranded (closed circles) and double-stranded (open circles) DNA cleavage mediated by the human enzyme. The effects of etoposide (green), a widely prescribed anti-cancer drug, on topoisomerase IIα are shown as a positive control. Error bars represent the SD of at least 3 independent experiments.

Conclusions.

Tuberculosis is one of the leading causes of morbidity worldwide and drug resistance and intolerance are prevalent. Consequently, there is a desperate need for the development of new anti-tubercular drugs that overcome resistance and/or are better tolerated by patients. Although there is a continual search for new drug targets, another approach is to develop novel compounds with high activity against validated targets, but that still retain activity in the face of current resistance profiles.

MGIs were selected for activity against M. tuberculosis, and, based on genetic studies and their structural similarities to NBTIs, they were believed to target gyrase.27 However, little was known about their interactions with the M. tuberculosis type II enzyme. Therefore, we characterized the activity of two MGIs against M. tuberculosis gyrase. Results indicate that MGIs are potent gyrase poisons. These compounds induce only single-stranded enzyme-mediated DNA breaks and suppress the ability of gyrase to cut both strands of the double helix. MGIs appear to be selective for M. tuberculosis gyrase over other species, retain activity against the most common mutations that lead to fluoroquinolone resistance, and display no activity against human topoisomerase IIα. These findings suggest that MGIs have potential as anti-tubercular drugs, especially in the case of fluoroquinolone-resistant disease. The mechanistic studies described above provide a basis for future structure-activity studies directed toward improving drug activity, while addressing physiological toxicities and mutation rates.

METHODS

Enzymes and Materials.

Full-length wild-type M. tuberculosis gyrase subunits (GyrA and GyrB) and GyrA mutants (GyrAA90V, GyrAD94H, and GyrAD94G) were expressed and purified as described previously.31 E. coli topisomerase IV was provided by Keir C. Neuman (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at National Institutes of Health). B. anthracis gyrase was expressed and purified by Rachel E. Ashley as described previously.58 B. anthracis topoisomerase IV was expressed and purified as described previously.58 The N. gonorrhoeae enzymes and E. coli gyrase were provided by Pan Chan (GlaxoSmithKline). Human topoisomerase IIα was expressed in yeast and purified as described by Kingma et al.59

Negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA was prepared from E. coli using a Plasmid Mega Kit (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer. Positively supercoiled pBR322 DNA was prepared by treating negatively supercoiled molecules with recombinant Archaeoglobus fulgidus reverse gyrase.60–61 The number of positive supercoils induced by this process is comparable to the number of negative supercoils in the original pBR322 preparations.60 In the experiments that compared negatively and positively supercoiled DNA, the negatively supercoiled plasmid preparations were processed identically to the positively supercoiled molecules except that reaction mixtures did not contain reverse gyrase. Relaxed pBR322 plasmid DNA was generated by treating negatively supercoiled pBR322 with calf thymus topoisomerase I (Invitrogen) and purified as described previously.62

The MGIs GSK000 and GSK325 and the NBTI GSK126 were synthesized as described previously by Blanco et al.27 In the paper by Blanco et al., GSK126, GSK325, and GSK000 were identified as compounds 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Moxifloxacin was obtained from LKT Laboratories. The MGIs and moxifloxacin were stored at 4 °C as 20 mM stock solutions in 100% dimethylsulfoxide.

Molecular Modeling.

The structure of GSK000 in a ternary complex with M. tuberculosis gyrase was modeled using Coot,63 MOE,64 and Maestro (Schrödinger Release 2017-2: Maestro, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2017). Drug placement was based on the crystal structure of the NBTI GSK299423 in a ternary complex with Staphylococcus aureus gyrase [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 2XCS] and the crystal structure of a cleavage complex of M. tuberculosis gyrase with moxifloxacin (PDB code 5BTA).

DNA Cleavage.

DNA cleavage reactions were based on the procedure of Aldred et al.55 Reactions were carried out in the presence or absence of MGIs/NBTI or moxifloxacin and contained 100 nM wild-type or mutant (GyrAA90V, GyrAD94H, and GyrAD94G) gyrase (2:1 GyrA:GyrB ratio) and 10 nM positively or negatively supercoiled pBR322 in a total volume of 20 μL of cleavage buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 40 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, and 10% glycerol]. In some cases, 1 mM ATP was included in reaction mixtures, or the MgCl2 in the cleavage buffer was replaced with 6 mM CaCl2 or. Unless stated otherwise, reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes were trapped by adding 2 μL of 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate followed by 2 μL of 250 mM Na2EDTA and 2 μL of 0.8 mg/mL Proteinase K (Sigma Aldrich). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 45 °C for 30 min to digest the topoisomerases. Samples were mixed with 2 μL of 60% sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5% bromophenol blue; and 0.5% xylene cyanol FF and were incubated at 45 °C for 2 min before loading onto 1% agarose gels. Reaction products were subjected to electrophoresis in a buffer of 40 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.3) and 2 mM EDTA that contained 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. DNA bands were visualized with medium-range ultraviolet light and quantified using an Alpha Innotech digital imaging system. DNA single- or double-stranded cleavage was monitored by the conversion of supercoiled plasmid to nicked or linear molecules, respectively and quantified in comparison to a control reaction in which an equal amount of DNA was digested by EcoRI (New England BioLabs).

DNA cleavage reactions with human topoisomerase IIα were performed as described previously.65 Reaction mixtures contained 150 nM topoisomerase IIα and 10 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA in 20 μL of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 2.5% (v/v) glycerol. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 6 min at 37 °C. Enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes were trapped, processed, subjected to electrophoresis, and DNA cleavage bands were visualized and quantified as described above.

DNA Ligation.

DNA ligation assays were carried out in the absence or presence of GSK000 or moxifloxacin following the procedure of Robinson and Osheroff.66 Reaction mixtures (20 μL) contained 100 nM wild-type M. tuberculosis gyrase and 10 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 in cleavage buffer. In experiments carried out in the absence of drug, MgCl2 in the cleavage buffer was replaced with 6 mM CaCl2 to increase baseline levels of DNA cleavage. DNA cleavage–religation equilibria were established at 37 °C for 10 min. Ligation was initiated by shifting the samples from 37 °C to 75 °C. Reactions were stopped at times ranging from 0 to 210 s by the addition of 2 μL of 5% SDS followed by 2 μL of 250 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Samples were digested with Proteinase K, processed, and visualized as described above. Levels of MGI-induced single-stranded and moxifloxacin induced double-stranded DNA cleavage were set to 1 at 0 s, and ligation was assessed by the loss of nicked or linear reaction product, respectively, over time.

Persistence of Gyrase-DNA Cleavage Complexes.

The persistence of gyrase-DNA cleavage complexes in the absence or presence of GSK000 or moxifloxacin was determined using the procedure of Aldred et al.55 Initial reaction mixtures contained 500 nM gyrase, 50 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322, and 10 μM GSK000 or 50 μM moxifloxacin in cleavage buffer a total volume of 20 μL. In experiments carried out in the absence of drug, the MgCl2 in the cleavage buffer was replaced with 6 mM CaCl2 to increase baseline levels of DNA cleavage. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min to allow cleavage complexes to form, and were then diluted 20–fold with 1X reaction buffer warmed to 37 °C. Samples (20 μL) were removed at times ranging from 0–240 min. DNA cleavage was stopped and samples were digested with Proteinase K, processed, and visualized as described above. Levels of MGI-induced single-stranded and moxifloxacin-induced double-stranded DNA cleavage were set to 1 at time zero, and the persistence (stability) of cleavage complexes was determined by the loss of single- or double-stranded DNA cleavage, respectively, over time.

DNA Cleavage Site Utilization.

DNA cleavage sites were mapped using a modification67 of the procedure of O’Reilly and Kreuzer.68 The pBR322 DNA substrate was linearized by treatment with HindIII. Terminal 5′-phosphates were removed by treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and were replaced with [32P]phosphate using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ–32P]ATP. The DNA was then treated with EcoRI, and the 4332-base pair singly end-labeled fragment was purified from the small EcoRI–HindIII fragment by passing it through a CHROMA SPIN+TE-100 column (Clontech). Reaction mixtures contained 500 nM wild-type M. tuberculosis gyrase and 5 nM radiolabeled pBR322 DNA substrate in 50 μL of DNA cleavage buffer with 6 mM CaCl2 in the absence or presence of MGIs or moxifloxacin. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, and enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes were trapped by the addition of 5 μL of 10% SDS followed by 3 μL of 250 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Proteinase K (5 μL of a 0.8 mg/mL solution) was added, and samples were incubated at 45 °C for 30 min to digest the enzyme. Alternatively, cleavage complexes were enriched by K+-SDS precipitation of gyrase, prior to Proteinase K treatment.69 This was accomplished by adding 25 μL of 2.5 M KCl and incubating at −20 °C for 10 min. Mixtures were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min. Pellets were resuspended in 50 μL of 10 mM Tris-borate (pH 7.9) and 1 mM EDTA and were then treated with Proteinase K as described above. In both cases, DNA products were precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 6 μL of 40% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 0.02% bromophenol blue, and 0.02% xylene cyanol FF. Samples were heated at 75 °C for 2 min and were subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel in 100 mM Tris-borate (pH 8.3) and 2 mM EDTA. Gels were dried in vacuo, and DNA cleavage products were visualized with a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX.

DNA Supercoiling and Relaxation.

DNA supercoiling/relaxation assays were based on previously published protocols.31, 55 Assays contained 75 nM gyrase (1.5:1 GyrA:GyrB ratio), 5 nM relaxed or positively supercoiled pBR322, 1.5 mM ATP, and 1 mM DTT in 20 μL of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 80 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, and 10 % glycerol. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min (DNA supercoiling assays) or 1 min (DNA relaxation assays). The chosen assay lengths represent the minimum time required to completely supercoil or relax the DNA in the absence of drug. Reaction mixtures were stopped by the addition of 3 μL of a mixture of 0.77% SDS and 77.5 mM Na2EDTA. Samples were mixed with 2 μL of 60% sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5% bromophenol blue, and 0.5% xylene cyanol FF and were incubated at 45 °C for 2 min before loading onto 1% agarose gels in 100 mM Tris-borate (pH 8.3) and 2 mM EDTA. Gels were stained with 1 μg/mL ethidium bromide for 30 min. DNA bands were visualized with medium-range ultraviolet light as described above.

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs).

MIC values for GSK000, GSK325, and GSK126 against cultured E. coli (7623) cells were determined as described in Blanco, et al. 27

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Rachel E. Ashley, Dr. Keir C. Neuman, and Dr. Pan Chan for generously supplying some of the enzymes used in this study. We also thank Rachel E. Ashley, Esha D. Dalvie, Lorena Infante Lara, and Alexandria A. Oviatt for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the US Veterans Administration (Merit Review award I01 Bx002198 to N.O.) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM126363 to N.O. and R01 CA077373 to J.M.B.). E.G.G was supported by the Pharmacology Training Grant (5T32GM007628) and pre-doctoral fellowships from the PhRMA Foundation and the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists. T.R.B. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization Long-Term Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Namdar R; Lauzardo M; Peloquin CA, Tuberculosis In Pharmacotherapy : a pathophysiologic approach, 9th edition ed.; DiPiro JT, Ed. McGraw-Hill: New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO, Global tuberculosis report 2016. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Tuberculosis Fact Sheet http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/.

- 4.WHO, Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines. 4th ed.; WHO Press: Geneva, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeon D, WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2016 Update: applicability in South Korea. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. (Seoul). 2017, 80 (4), 336–343. DOI: 10.4046/trd.2017.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper DC, Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Drug Resistance Updates. 1999, 2 (1), 38–55. DOI: 10.1054/drup.1998.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson VE; Osheroff N, Type II topoisomerases as targets for quinolone antibacterials: turning Dr. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde. Curr. Pharm. Des 2001, 7 (5), 337–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drlica K; Hiasa H; Kerns R; Malik M; Mustaev A; Zhao X, Quinolones: action and resistance updated. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2009, 9 (11), 981–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruri F; Sterling TR; Kaiga AW; Blackman A; van der Heijden YF; Mayer C; Cambau E; Aubry A, A systematic review of gyrase mutations associated with fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and a proposed gyrase numbering system. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2012, 67 (4), 819–831. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkr566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldred KJ; Kerns RJ; Osheroff N, Mechanism of quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry. 2014, 53 (10), 1565–1574. DOI: 10.1021/bi5000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper DC; Jacoby GA, Mechanisms of drug resistance: quinolone resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2015, 1354, 12–31. DOI: 10.1111/nyas.12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson EG; Ashley RE; Kerns RJ; Osheroff N, Fluoroquinolone interactions with bacterial type II topoisomerases and target-mediated drug resistance In Antimicrobial Resistance and Implications for the 21st Century, Drlica K; Shlaes D; Fong IW, Eds. Springer: in press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine C; Hiasa H; Marians KJ, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV: biochemical activities, physiological roles during chromosome replication, and drug sensitivities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998, 1400, 29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sissi C; Palumbo M, In front of and behind the replication fork: bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2010, 67 (12), 2001–2024. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-010-0299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SH; Chan NL; Hsieh TS, New mechanistic and functional insights into DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2013, 82, 139–170. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush NG; Evans-Roberts K; Maxwell A, DNA topoisomerases. EcoSal Plus. 2015, 6 (2). DOI: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0010-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiasa H; Marians KJ, Topoisomerase IV can support oriC DNA replication in vitro. J. Biol. Chem 1994, 269 (23), 16371–16375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster DA; Crut A; Shuman S; Bjornsti MA; Dekker NH, Cellular strategies for regulating DNA supercoiling: a single-molecule perspective. Cell. 2010, 142 (4), 519–530. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zechiedrich EL; Khodursky AB; Bachellier S; Schneider R; Chen D; Lilley DM; Cozzarelli NR, Roles of topoisomerases in maintaining steady-state DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275 (11), 8103–8113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X; Reyes-Lamothe R; Sherratt DJ, Modulation of Escherichia coli sister chromosome cohesion by topoisomerase IV. Genes Dev. 2008, 22 (17), 2426–2433. DOI: 10.1101/gad.487508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z; Deibler RW; Chan HS; Zechiedrich L, The why and how of DNA unlinking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37 (3), 661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vos SM; Tretter EM; Schmidt BH; Berger JM, All tangled up: how cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2011, 12 (12), 827–841. DOI: 10.1038/nrm3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aubry A; Fisher LM; Jarlier V; Cambau E, First functional characterization of a singly expressed bacterial type II topoisomerase: the enzyme from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2006, 348 (1), 158–165. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole ST; Brosch R; Parkhill J; Garnier T; Churcher C; Harris D; Gordon SV; Eiglmeier K; Gas S; Barry CE 3rd; Tekaia F; Badcock K; Basham D; Brown D; Chillingworth T; Connor R; Davies R; Devlin K; Feltwell T; Gentles S; Hamlin N; Holroyd S; Hornsby T; Jagels K; Krogh A; McLean J; Moule S; Murphy L; Oliver K; Osborne J; Quail MA; Rajandream MA; Rogers J; Rutter S; Seeger K; Skelton J; Squares R; Squares S; Sulston JE; Taylor K; Whitehead S; Barrell BG, Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998, 393 (6685), 537–544. DOI: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tretter EM; Berger JM, Mechanisms for defining supercoiling set point of DNA gyrase orthologs: II. The shape of the GyrA subunit C-terminal domain (CTD) is not a sole determinant for controlling supercoiling efficiency. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287 (22), 18645–18654. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.345736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bax BD; Chan PF; Eggleston DS; Fosberry A; Gentry DR; Gorrec F; Giordano I; Hann MM; Hennessy A; Hibbs M; Huang J; Jones E; Jones J; Brown KK; Lewis CJ; May EW; Saunders MR; Singh O; Spitzfaden CE; Shen C; Shillings A; Theobald AJ; Wohlkonig A; Pearson ND; Gwynn MN, Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature. 2010, 466 (7309), 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco D; Perez-Herran E; Cacho M; Ballell L; Castro J; Gonzalez Del Rio R; Lavandera JL; Remuinan MJ; Richards C; Rullas J; Vazquez-Muniz MJ; Woldu E; Zapatero-Gonzalez MC; Angulo-Barturen I; Mendoza A; Barros D, Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase inhibitors as a new class of antitubercular drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2015, 59 (4), 1868–1875. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.03913-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan PF; Germe T; Bax BD; Huang J; Thalji RK; Bacque E; Checchia A; Chen D; Cui H; Ding X; Ingraham K; McCloskey L; Raha K; Srikannathasan V; Maxwell A; Stavenger RA, Thiophene antibacterials that allosterically stabilize DNA-cleavage complexes with DNA gyrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114 (22), E4492–E4500. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1700721114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougherty TJ; Nayar A; Newman JV; Hopkins S; Stone GG; Johnstone M; Shapiro AB; Cronin M; Reck F; Ehmann DE, NBTI 5463 is a novel bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitor with activity against gram-negative bacteria and in vivo efficacy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58 (5), 2657–2664. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.02778-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiasa H, DNA topoisomerases as targets for antibacterial agents. Methods Mol. Biol 2018, 1703, 47–62. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7459-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aldred KJ; Blower TR; Kerns RJ; Berger JM; Osheroff N, Fluoroquinolone interactions with Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase: Enhancing drug activity against wild-type and resistant gyrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113 (7), E839–846. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1525055113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bromberg KD; Burgin AB; Osheroff N, A two-drug model for etoposide action against human topoisomerase IIα. J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278 (9), 7406–7412. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M212056200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muslimovic A; Nystrom S; Gao Y; Hammarsten O, Numerical analysis of etoposide induced DNA breaks. PLoS One. 2009, 4 (6), e5859 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashley RE; Lindsey RH Jr.; McPherson SA; Turnbough CL Jr.; Kerns RJ; Osheroff N, Interactions between quinolones and Bacillus anthracis gyrase and the basis of drug resistance. Biochemistry. 2017, 56 (32), 4191–4200. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blower TR; Williamson BH; Kerns RJ; Berger JM, Crystal structure and stability of gyrase-fluoroquinolone cleaved complexes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113 (7), 1706–1713. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1525047113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laponogov I; Pan XS; Veselkov DA; McAuley KE; Fisher LM; Sanderson MR, Structural basis of gate-DNA breakage and resealing by type II topoisomerases. PLoS One. 2010, 5 (6), e11338 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laponogov I; Sohi MK; Veselkov DA; Pan XS; Sawhney R; Thompson AW; McAuley KE; Fisher LM; Sanderson MR, Structural insight into the quinolone-DNA cleavage complex of type IIA topoisomerases. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2009, 16 (6), 667–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S; Jung SR; Heo K; Byl JA; Deweese JE; Osheroff N; Hohng S, DNA cleavage and opening reactions of human topoisomerase IIα are regulated via Mg2+-mediated dynamic bending of gate-DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109 (8), 2925–2930. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1115704109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deweese JE; Burgin AB; Osheroff N, Using 3’-bridging phosphorothiolates to isolate the forward DNA cleavage reaction of human topoisomerase IIα. Biochemistry. 2008, 47 (13), 4129–4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deweese JE; Osheroff N, Coordinating the two protomer active sites of human topoisomerase IIa: nicks as topoisomerase II poisons. Biochemistry. 2009, 48 (7), 1439–1441. DOI: 10.1021/bi8021679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osheroff N; Zechiedrich EL, Calcium-promoted DNA cleavage by eukaryotic topoisomerase II: trapping the covalent enzyme-DNA complex in an active form. Biochemistry. 1987, 26, 4303–4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan PF; Srikannathasan V; Huang J; Cui H; Fosberry AP; Gu M; Hann MM; Hibbs M; Homes P; Ingraham K; Pizzollo J; Shen C; Shillings AJ; Spitzfaden CE; Tanner R; Theobald AJ; Stavenger RA; Bax BD; Gwynn MN, Structural basis of DNA gyrase inhibition by antibacterial QPT-1, anticancer drug etoposide and moxifloxacin. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 10048 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms10048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Sullivan DM; Hinds J; Butcher PD; Gillespie SH; McHugh TD, Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA repair in response to subinhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2008, 62 (6), 1199–1202. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkn387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deweese JE; Osheroff N, The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: wolf in sheep’s clothing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37 (3), 738–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li TK; Liu LF, Tumor cell death induced by topoisomerase-targeting drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2001, 41, 53–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu LF; D’Arpa P, Topoisomerase-targeting antitumor drugs: mechanisms of cytotoxicity and resistance. Important Adv. Oncol 1992, 79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClendon AK; Osheroff N, The geometry of DNA supercoils modulates topoisomerase-mediated DNA cleavage and enzyme response to anticancer drugs. Biochemistry. 2006, 45 (9), 3040–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashley RE; Blower TR; Berger JM; Osheroff N, Recognition of DNA supercoil geometry by Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase. Biochemistry. 2017, 56 (40), 5440–5448. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long R; Chong H; Hoeppner V; Shanmuganathan H; Kowalewska-Grochowska K; Shandro C; Manfreda J; Senthilselvan A; Elzainy A; Marrie T, Empirical treatment of community-acquired pneumonia and the development of fluoroquinolone-resistant tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis 2009, 48 (10), 1354–1360. DOI: 10.1086/598196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devasia RA; Blackman A; Gebretsadik T; Griffin M; Shintani A; May C; Smith T; Hooper N; Maruri F; Warkentin J; Mitchel E; Sterling TR, Fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: the effect of duration and timing of fluoroquinolone exposure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 2009, 180 (4), 365–370. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0146OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grossman RF; Hsueh PR; Gillespie SH; Blasi F, Community-acquired pneumonia and tuberculosis: differential diagnosis and the use of fluoroquinolones. Int. J. Infect. Dis 2014, 18, 14–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JY; Lee HJ; Kim YK; Yu S; Jung J; Chong YP; Lee SO; Choi SH; Shim TS; Kim YS; Woo JH; Kim SH, Impact of fluoroquinolone exposure prior to tuberculosis diagnosis on clinical outcomes in immunocompromised patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2016, 60 (7), 4005–4012. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01749-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaba PD; Haley C; Griffin MR; Mitchel E; Warkentin J; Holt E; Baggett P; Sterling TR, Increasing outpatient fluoroquinolone exposure before tuberculosis diagnosis and impact on culture-negative disease. Arch. Intern. Med 2007, 167 (21), 2317–2322. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elsea SH; Osheroff N; Nitiss JL, Cytotoxicity of quinolones toward eukaryotic cells. Identification of topoisomerase II as the primary cellular target for the quinolone CP-115,953 in yeast. J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267 (19), 13150–13153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aldred KJ; McPherson SA; Wang P; Kerns RJ; Graves DE; Turnbough CL Jr.; Osheroff N, Drug interactions with Bacillus anthracis topoisomerase IV: biochemical basis for quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry. 2012, 51 (1), 370–381. DOI: 10.1021/bi2013905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aldred KJ; Schwanz HA; Li G; Williamson BH; McPherson SA; Turnbough CL Jr.; Kerns RJ; Osheroff N, Activity of quinolone CP-115,955 against bacterial and human type II topoisomerases is mediated by different interactions. Biochemistry. 2015, 54 (5), 1278–1286. DOI: 10.1021/bi501073v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baldwin EL; Osheroff N, Etoposide, topoisomerase II and cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents. 2005, 5 (4), 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dong S; McPherson SA; Wang Y; Li M; Wang P; Turnbough CL Jr.; Pritchard DG, Characterization of the enzymes encoded by the anthrose biosynthetic operon of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol 2010, 192 (19), 5053–5062. DOI: 10.1128/JB.00568-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kingma PS; Greider CA; Osheroff N, Spontaneous DNA lesions poison human topoisomerase IIα and stimulate cleavage proximal to leukemic 11q23 chromosomal breakpoints. Biochemistry. 1997, 36 (20), 5934–5939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McClendon AK; Rodriguez AC; Osheroff N, Human topoisomerase IIα rapidly relaxes positively supercoiled DNA: implications for enzyme action ahead of replication forks. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280 (47), 39337–39345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez AC, Studies of a positive supercoiling machine: nucleotide hydrolysis and a multifunctional “latch” in the mechanism of reverse gyrase. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277 (33), 29865–29873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aldred KJ; Breland EJ; Vlčková V; Strub MP; Neuman KC; Kerns RJ; Osheroff N, Role of the water-metal ion bridge in mediating interactions between quinolones and Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV. Biochemistry. 2014, 53 (34), 5558–5567. DOI: 10.1021/bi500682e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emsley P, Tools for ligand validation in Coot. Acta. Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol 2017, 73 (Pt 3), 203–210. DOI: 10.1107/S2059798317003382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.ULC CCG Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fortune JM; Osheroff N, Merbarone inhibits the catalytic activity of human topoisomerase IIα by blocking DNA cleavage. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273 (28), 17643–17650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson MJ; Martin BA; Gootz TD; McGuirk PR; Moynihan M; Sutcliffe JA; Osheroff N, Effects of quinolone derivatives on eukaryotic topoisomerase II: A novel mechanism for enhancement of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. J. Biol. Chem 1991, 266 (22), 14585–14592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baldwin EL; Byl JA; Osheroff N, Cobalt enhances DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα in vitro and in cultured cells. Biochemistry. 2004, 43 (3), 728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O’Reilly EK; Kreuzer KN, A unique type II topoisomerase mutant that is hypersensitive to a broad range of cleavage-inducing antitumor agents. Biochemistry. 2002, 41 (25), 7989–7997. DOI: bi025897m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trask DK; DiDonato JA; Muller MT, Rapid detection and isolation of covalent DNA/protein complexes: application to topoisomerase I and II. EMBO J 1984, 3 (3), 671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]