Abstract

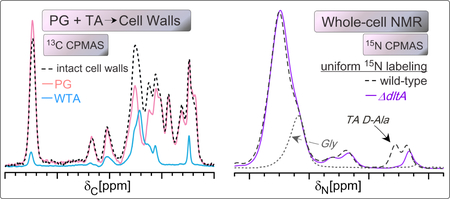

Gram-positive bacteria surround themselves with a multi-layered macromolecular cell wall that is essential to cell survival and serves as a major target for antibiotics. The cell wall of S. aureus is composed of two major structural components, peptidoglycan (PG) and wall teichoic acid (WTA), together creating a heterogeneous and insoluble matrix that poses a challenge to quantitative compositional analysis. Here, we present 13C CPMAS solid-state NMR spectra of intact cell walls, purified PG, and purified WTA. The spectra reveal the clear molecular differences in the two polymers and enable quantification of PG and WTA in isolated cell walls, an attractive alternative to estimating teichoic acid content from a phosphate analysis of completely pyrolyzed cell walls. Furthermore, we discovered that unique PG and WTA spectral signatures could be identified in whole-cell NMR spectra and used to compare PG and WTA levels among intact bacterial cell samples. The distinguishing whole cell 13C NMR contributions associated with PG include the GlcNAc-MurNAc sugar carbons and glycyl alpha-carbons. WTA contributes carbons from the phosphoribitol backbone. Distinguishing 15N spectral signatures include glycyl amide nitrogens in PG and the esterified D-alanyl amine nitrogens in WTA. 13C NMR analysis was performed with samples at natural abundance and included ten whole-cell sample comparisons. Changes consistent with altered PG and WTA content were detected in whole-cell spectra of bacteria harvested at different growth times and in cells treated with tunicamycin. This use of whole-cell NMR provides quantitative parameters of composition in the context of whole cell activity.

Keywords: cell wall, peptidoglycan, teichoic acid, solid-state NMR, whole-cell NMR

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Gram-positive bacteria surround themselves with a thick cell wall that is essential to cell survival and is a major target of antibiotics. The cell wall is composed primarily of two polymeric macromolecules: peptidoglycan (PG) and wall teichoic acids (WTAs), with their chemical structures in S. aureus provided in Figure 1. Bacterial cell wall composition, assembly, and function have been intensely investigated over many decades. This rich history is a result of the natural and intense curiosity to understand how such a self-assembly process occurs, coupled with the urgent need for new strategies to prevent and treat infectious diseases.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of PG and TA.

(A) In S. aureus, peptidoglycan is composed of a repeating unit of the disaccharide N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc)-(β−1,4)-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) with an attached peptide stem that is cross-linked to a neighboring peptide stem through the pentaglycine bridge of one stem and the penultimate D-Ala of the neighboring stem. Crosslink formation occurs with the loss of the terminal D-Ala. (B) Wall teichoic acids are composed of long chains of polyribitol phosphate (35–40 units) and are covalently anchored to peptidoglycan through a short (1–3 units) polyglycerol phosphate bridge and the disaccharide N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc)-(β1→4)-GlcNAc. The ribitol phosphate units are additionally modified with GlcNAc and D-Ala esters. Anomeric carbons are highlighted in red, and glycine amide nitrogens and the TA D-Ala amine are highlighted in blue.

The inhibition of cell-wall synthesis is a well-pursued avenue for the identification of antibiotics, where most cell-wall targeting antibiotics are thought to inhibit specific steps in PG biosynthesis or inhibit very early steps in cell-wall synthesis central to both PG and WTA.1 PG assembly is essential to cell viability and provides the strong yet dynamic structural scaffolding that surrounds and mechanically protects cells from their internal turgor pressure. Core enzymatic steps in peptidoglycan synthesis have been carefully elaborated and require the coordinated activity of more than ten proteins.2 PG biosynthesis begins in the cytoplasm, ultimately leading to the production of Lipid II, the complete PG subunit (Figure 1) attached to the membrane-associated bactoprenol-pyrophosphate lipid carrier.3 Lipid II is then translocated to the outside of the cell through the newly appreciated role of a flippase, whose mode of action is of intense interest and under study.4 At the cell surface, the PG subunit is released from the lipid carrier and added to existing PG through the action of transglycosylation and transpeptidation. Cell-wall associated proteins can also be covalently linked to the terminus of the glycyl bridge in place of a cell wall crosslink to another PG subunit. Additional cell wall biosynthesis proteins remain under study for their potential roles as flippases and as additional transglycosylation and transpeptidation enzymes.5

WTAs are covalently attached to PG MurNAc residues, a process that occurs outside the cell.6 Cell wall modification with WTA is implicated in virulence and host adherence,7 decreased antibiotic susceptibility, 8,9 and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and antibodies.10 Thus, although PG biosynthesis has long been a target for effective antibiotics, targeting WTA biosynthesis is an attractive approach to inhibit virulence and to increase susceptibility of bacteria to currently available antibiotics.11,12 In addition, targeting WTA assembly holds promise to inhibit viability vis-à-vis antibacterial activity.13 WTA had not traditionally been considered as essential to cell growth. This is because strains that cannot produce WTA and cells treated with inhibitors that affect the very first stages of WTA synthesis are viable, even though they exhibit altered morphology and septation.12 However, inhibition of later stages of WTA synthesis can be lethal, thus revealing a specific target for antibacterial development.14

WTA biosynthesis begins in the cytoplasm to produce the C55-lipid-linked immature WTA polymer, the ManNAc-GlcNAc disaccharide followed by three glycerol phosphates and then a longer polymer of ribitol phosphate groups (~40 units).15 Ribitol units can be modified with GlcNAc while still on the cytosolic side of the membrane.16 Transporter proteins flip the extended WTA polymer to the extracellular surface,17 where it is linked to PG.6,18 D-alanylation of ribitol units is thought to occur extracellularly and is mediated by the DltA, DltB, DltC, and DltD proteins.19 Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is also produced by Gram-positive bacteria, but is integrally associated with the cell membrane. LTA synthesis follows an independent pathway, with an important distinction of being composed of polyglycerol phosphate groups, not ribitol phosphate as in WTA. In contrast to ribitol in WTA, the glycerol in LTA only has one hydroxyl functional group and it can be modified with either GlcNAc or D-Ala.20–22

Many currently available antibiotics target PG biosynthesis. For example, fosfomycin inhibits MurA and prevents the synthesis of MurNAc in the cytosol.23 Vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic, sequesters the cell-wall precursor, Lipid II, at the cell surface, prevents subunit incorporation into the growing PG strands, and reduces the supply of lipid carrier available for further peptidoglycan synthesis.24 Yet, for some antibiotics, ambiguities from available experiments prevent a definitive determination of the molecular basis of action during cell growth. For example, the beta-lactams and cephalosporins inhibit PG assembly by inhibiting crosslinking as a substrate mimic and suicide inhibitor of transpeptidation domains of penicillin-binding proteins, so named for this activity.1 However, there has been a recent resurgence in mechanistic studies to examine beta lactam antibiotic modes of action in terms of cell killing activity. Work with E. coli, for example, demonstrated that the cell killing activity of mecillinam is more complex and includes activation of a futile cycle of cell wall production and turnover that depletes available PG precursors.25 A newly identified antibiotic, teixobactin, binds to isolated lipid-linked precursors of both peptidoglycan and teichoic acids in vitro, as observed in a thin layer chromatography binding assay.26 Yet, teixobactin’s precise mechanism or multiple mechanisms operating during growth is uncertain.27 Lysobactin was also observed to bind both PG and WTA-lipid linked precursors through in vitro enzymatic competition assays, although the killing action was more recently suggested to be due to its Lipid II binding activity through observation of an accumulation of Lipid II in lipid extracts of treated cells.28 Complementary avenues of investigation to examine antibiotic modes of action during cell growth are always desired.29

New methods are continually being introduced to probe and evaluate cell-wall assembly in vivo to address ambiguities that can result during investigations of antibiotic modes of action, particularly given the challenge of identifying and quantifying chemical and structural changes to the insoluble cell wall polymers. Classical approaches include the tracking of radiolabeled cell wall precursors through the steps of synthesis and the analysis of enzymatic and acid digests of cell walls by chromatographic separation and detection (e.g. HPLC or LC-MS).30 These classic techniques work especially well and can provide quantitative data in Gram-negative bacteria with their completely hydrolyzable PG. In S. aureus, however, the PG cannot be completely solubilized; even after extensive digestion by cell wall hydrolases and acid, an inseparably crosslinked, high-molecular weight polymer remains. This incomplete dissolution prevents a complete accounting of PG components by solution-based methods such as HPLC.31 Newer methods include strategies to fluorescently label peptidoglycan for live-cell imaging.32 Although fluorescently labeled amino acid analogues can be cytotoxic, in limited concentrations they enable visualization of analogue incorporation into the cell wall to characterize, for example, the activity of different penicillin binding proteins and the spatial mapping of cell-wall synthesis sites.33 Studies to establish the intermediates and products of peptidoglycan synthesis have additionally leveraged creative biochemical experiments including in vitro reconstruction of the enzymatic pathways.6

Towards the goal of obtaining parameters of composition and architecture in cell walls and whole cells, we have introduced strategies using solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Quantitative determinations can be made of lysyl coupling to the pentaglycine bridge (bridge-links) and of D-Ala-Gly crosslinks through non-perturbative labeling during cell growth using selectively 13C-and 15N-labeled amino acids.34,35 Whole cell NMR of S. aureus treated with vancomycin suggested that vancomycin sequesters Lipid II, thereby preventing transglycosylation and does not significantly influence transpeptidation.34 Internuclear distances have also been measured between antibiotics and cell-wall sites in whole cells35 and additional reports have measured parameters of cell-wall architecture.36–38 In addition, solid-state NMR analysis of intact cell wall samples provided quantitative ratios of distinct types of PG units that are not possible with HPLC analysis that reports only on the soluble material liberated from attempted digestion of the cell wall [32]. 31P solid-state NMR analyses of teichoic acids have also addressed dynamics of the WTA and the binding of metal cations. 39,40 In addition, mass spectrometry has been employed to detect teichoic acids produced by clinical isolates.41

As debate continues over how some antibiotics, like the beta-lactams, function to cause cell death in bacteria,25 solid-state NMR offers a means to extract chemical and structural information about cell wall composition and antibiotic action. We present here a new strategy, demonstrating that interpretable and quantifiable spectral changes in cell walls and whole-cell samples can report on changes to PG and WTA without any selective labeling. Samples are either examined at natural abundance 13C or through previously-reported uniform labeling in which all carbons are 13C-labeled or all nitrogens are 15N-labeled in the cell wall and whole cell samples.42,43 We present an extensive comparative sample analysis, including ten whole-cell NMR samples and cells treated with a teichoic acid inhibitor (tunicamycin) to emphasize the sensitivity of the whole-cell NMR approach.

Materials and methods

Bacterial cultures and whole-cell NMR sample preparation

S. aureus strains were routinely maintained on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates or in tryptic soy broth (TSB). Uniformly-labeled S. aureus (strain MW2 and mutants MW2ΔtarO and MW2ΔdltA) were prepared from growth in a modified version of S. aureus synthetic medium (SASM). As previously described, the modified SASM contained a uniformly-labeled 13C and 15N algal amino acid extract instead of the individual twenty amino acids, and had glucose and ammonium sulfate replaced with their uniformly-labeled 13C and 15N counterparts, respectively.42 Bacteria prepared with selective labels, either L-[ε−15N]lysine or [15N]glycine, were grown in standard SASM in which the indicated amino acid was replaced with its labeled counterpart. For D-[15N]alanine labeling, 100mg/L of D-[15N]alanine was added to regular SASM, and the cultures were grown with 10 μg/mL of alaphosphin, an alanine racemase inhibitor, to prevent scrambling of D-Ala and L-Ala.35 All bacterial cultures were grown to an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 1.0 (or an otherwise specified OD) at 37°C with 200 rpm shaking, and were harvested by three cycles of centrifugation at 10,000g and washing with 5 mM, pH 7.0 HEPES buffer. Final cell pellets were frozen with liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. Lyophilized sample pellets were used for solid-state NMR analysis. Most whole-cell samples were harvested from 300 mL of culture and yielded a cell pellet between 50–100 mg dry mass.

Isolated cell wall, PG, and WTA sample preparation

S. aureus MW2 cultures for cell wall, PG, and WTA isolations were grown as above to OD 4.0 in tryptic soy broth (no labels). Cell walls were isolated through an established protocol.31 Isolated PG was extracted following the same protocol, but used mutant S. aureus cells lacking the tarO gene necessary for WTA synthesis (MW2ΔtarO). Teichoic acids were liberated from wild-type (MW2) purified cell walls. This liberation involved treating purified cell walls with 30 mL of 0.1M sodium hydroxide for 18 hours at 37°C and 200 rpm shaking, followed by neutralization with 30 mL of 0.1M acetic acid. Centrifugation at 38,000 g for 1 hour removed non-hydrolyzed cell wall components, and the supernatant containing WTA was collected, dialyzed extensively against water in a 3.5 kDa MWCO dialysis membrane, and then flash frozen and lyophilized for NMR studies.

Solid-State NMR spectroscopy

Solid-state NMR experiments were performed using an 89-mm 11.7 T wide-bore magnet (500.92 MHz for 1H, 125.96 MHz for 13C, and 50.76 MHz for 15N); a Varian console with VNMRJ software; and a home-built four-frequency transmission-line probe with a 13.6 mm long, 6 mm inner diameter sample coil, and a Revolution NMR magic angle spinning Vespel stator. American Microwave Technology RF power pulse amplifiers (M3445B, 2 kW,Herley Inc.) were used to produce radio-frequency pulses for 15N (50 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) while the 1H (499 MHz) radio-frequency pulses were generated by a 2 kW tube amplifier (Amplifier System Inc., Herley Inc.) driven by a 50 W American Microwave Technology power amplifier (M3900C-2, Herley Inc.) under active control.44

Samples were spun at 7143 +/− 2 Hz in thin-wall 5 mm outer diameter zirconia rotors. The temperature was maintained at ~5°C, controlled by a variable temperature stack (FTS Systems Inc.). 13C or 15N CPMAS45 - spectra were obtained with a contact time of 1.5 ms, with spin-echo detection, and a recycle delay of 2.0 s. Field strengths for 13C and 15N cross-polarization were all 50 kHz with π-pulses of 10 μs and with a 10% linear 1H ramp centered at 57 kHz. 1H decoupling was performed at 72 kHz (continuous wave) during acquisition. The CPMAS mixing time was 1.5 ms and the recycle time was 2.0 s for all experiments. The CP mixing time was incremented between 0.5 ms and 8 ms for CP array experiments. 13C chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane as 0.0 ppm using a solid adamantine sample at 38.5 ppm. The 15N chemical shift scale is referenced to ammonia as 0 ppm.

NMR spectral analysis

For estimating PG and WTA carbon contributions to whole cells, 13C CPMAS spectra of PG and WTA were added until the summed spectrum best recapitulated the full cell wall spectral intensity, noting the expected intensity match between the glycyl alpha carbon peak in the cell wall and PG spectra, wherein WTA does not contain glycine. The integrated areas of the PG and WTA spectra were then used to calculate the percent of each component contributing to the cell wall spectrum to estimate the relative ratio of total PG versus WTA carbons. The carbon percentage was converted to an overall mass percentage using the average chemical formulas for PG (C46H82N14O22, 1206 gmol−1) and WTA (C544H1084N42O608P44, 18,199 gmol−1) units. These are the respective formulae for a pentaglycine-muropeptide PG unit, and an intact chain of WTA that is fully modified with N-acetylglucosamine and bearing 40 repeat units of ribitol phosphate.

Quantification of peak areas in the whole cell spectra were performed as follows. For whole-cell 13C CPMAS spectra, the anomeric carbon peak area at 101 ppm in each spectrum was well resolved and calculated using a Gaussian peak fit to the anomeric carbon peak using Matlab and provided in Figure S2. The calculated area was divided by total spectral area to provide a quantitative parameter of anomeric carbon contributions to each spectrum. The same protocol was used for the D-Ala amine nitrogen at 38 ppm in each uniformly labeled 15N whole-cell CPMAS spectrum. A specifically labeled 15N-Gly whole cell spectrum was available and this enabled the use of the experimental glycyl amide peak to be used directly for fitting and estimating the glycyl amide nitrogen contribution to each 15N spectrum, centered at 108 ppm. A simple integral of the total amide area (including the glycine) was also measured. Spectral plotting and fitting were performed using Matlab and Igor Pro software.

Inorganic Phosphate Determination

The inorganic phosphate content of cell walls, PG, and WTA was assayed through the method of Chen et al., as modified by Ames and Dubin.46,47 Briefly, isolated samples were re-suspended in deionized water to approximately 1 mg/mL. 20 μL of sample was mixed with 50 μL of 10% magnesium nitrate in ethanol. Samples were heated to dryness in a Bunsen burner, and ashed until no brown fumes evolved and a white powder remained. The powder was dissolved in 300 μL of 1M hydrochloric acid and was incubated for 1 hour. The samples were then mixed with 700 μL of a mixture of: one part 6N hydrochloric acid, one part 2.5% ammonium molybdate in water, two parts deionized water, and one part of freshly prepared 10% ascorbic acid in water. The mixtures were incubated at 45°C for 30 minutes, and then the absorbance at 820 nm was read. The absorbance of each sample was compared to phosphoric acid standards treated in the same manner to calculate the phosphate content.

Results

13C CPMAS spectra of purified peptidoglycan and wall teichoic acid

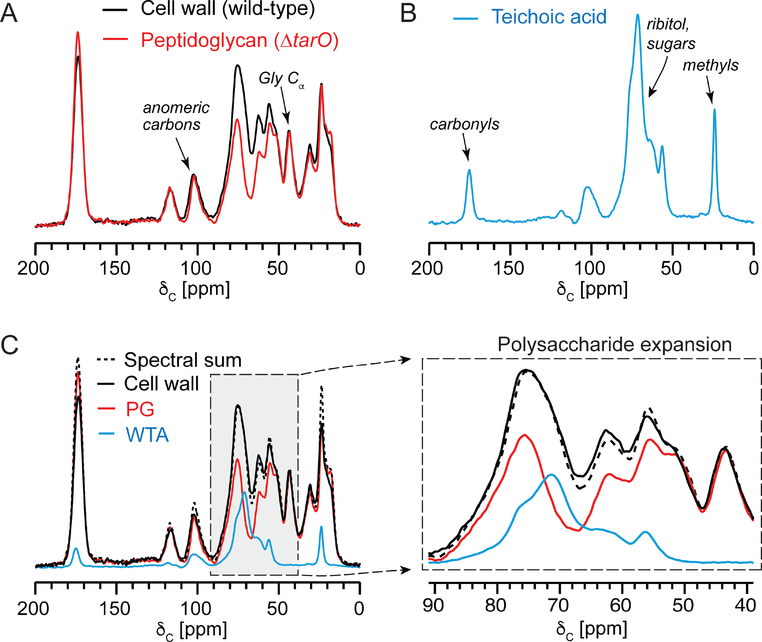

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy was employed to define and quantify the spectral contributions of PG and TA to S. aureus cell walls in situ. As revealed in previous work, a high-quality preparation of isolated cell walls yields a 13C CPMAS spectrum with well-defined peaks consistent with the carbon contributions expected for PG and WTA (i.e. anomeric carbons, ring-sugar carbons, ribitol carbons, and carbonyl and methyl carbons associated with glycan acetylation) as well as PG peptides, including the uniquely resolved glycine α-carbon peak at 42 ppm (Figure 2A).42 Here, for the first time, we present the 13C NMR spectra for separate samples of purified PG and purified WTA.

Figure 2. 13C CPMAS of isolated PG and WTA and spectral contributions to isolated cell walls.

(A) Natural abundance 13C CPMAS spectra of cell walls isolated from S. aureus MW2 (black) and from MW2ΔtarO (red). The cell walls from MW2ΔtarO represent only peptidoglycan. (B) The natural abundance 13C CPMAS spectrum of WTA isolated from MW2 cells. (C) A scaled spectral sum (black dashed line) of the WTA and PG spectra is presented as an overlay with the three individual sample spectra. The PG and WTA spectra were scaled such that the spectral sum matched the full intensity of the glycyl α-carbon and the polysaccharide region. All spectra were acquired with 32,768 scans and sample sizes were: 80 mg for cell walls, 20 mg for PG and 40 mg for WTA.

Purified PG was isolated from a S. aureus mutant unable to synthesize teichoic acid, MW2ΔtarO.48 Purified WTA was isolated through a procedure beginning with purified cell walls from wild-type cells. After isolation of intact cell walls, WTA was liberated into solution through alkaline hydrolysis and separated from PG through centrifugation. The only amino acid contributions to the isolated cell wall spectrum should originate from PG. WTA is D-alanylated in whole cells, but the esterified D-Ala is eliminated through hydrolysis during cell-wall isolations. Thus, a straightforward way to compare the contribution of the PG 13C spectrum to that of the intact cell walls is to normalize the two spectra by the glycine α-carbon peak, given that glycine in the cell wall only arises from PG and not at all from WTA. This comparison of the PG 13C NMR spectrum with the cell-wall spectrum first suggested that PG is the dominant contributor by carbon mass to the cell wall (Figure 2A). Second, the major spectral difference between these two was for carbon intensities unique to the isolated WTA 13C CPMAS spectrum, which is dominated by the ribitol carbons just upfield of the 78-ppm PG sugar region (Figure 2B). In addition, the WTA spectrum reports on the approximately one GlcNAc modification per ribitol unit, with acetyl group carbonyl and methyl carbon chemical shifts at 175 and 22 ppm, respectively. D-alanyl esters decorate WTA in the context of cells, but are hydrolyzed and removed during the cell wall isolation and, thus, not present in isolated WTA. Thus, we identified differentiating PG and TA carbon contributions to the one-dimensional 13C spectrum of isolated cell walls that will be of value in comparing PG and TA content among different intact cell wall preparations.

Teichoic acid and peptidoglycan contributions to cell walls

We sought to determine whether a spectral sum of the 13C spectra of the purified cell wall parts (PG and WTA) would recapitulate the 13C spectral intensity in the intact cell wall sample. This would enable a new approach to estimate PG and WTA content in isolated cell walls. If successful, the unique PG and WTA spectral signatures should also be able to report on PG and WTA content in unperturbed whole cell samples given the high percentage of cell wall by mass in whole cells.

Indeed, a spectral sum of the PG and WTA spectra recapitulated the spectrum of intact cell walls quite well in most peaks, with small differences in the peaks associated with acetylation (Figure 2C). The difference in acetylation is likely attributed to altered PG acetylation when PG is produced in the context of the tarO mutant, where PG would exhibit increased O-acetylation in the absence of TA or where the O-acetyl groups in MW2ΔtarO are more stable through the cell wall isolation protocol. Interestingly, O-acetylation of MurNAc in S. aureus is associated with resistance to lysozyme and acetylation can be influenced in different conditions.49,50 Nevertheless, to estimate the ratio of PG and WTA from the cell wall spectrum, the primary polysaccharide region of the spectrum and PG and WTA spectra were examined. A simple addition of the PG and WTA spectra in Figure 2 resulted in the close match to the polysaccharide region of the isolated cell wall spectrum and satisfied the expectation that the glycyl α-carbon peak intensity in the cell wall spectrum arises entirely from the PG spectrum, since WTA does not contain glycine. Through peak integration and converting the integrated carbon spectral area as a proxy for carbon mass percent to overall molecular mass percent, together with the average WTA chemical formula, we determined that TA accounts for 22% of the cell wall by mass, and PG makes up the remaining 78% in cells harvested at OD 4.0.

Teichoic acid levels are typically estimated by fully digesting cell wall material and quantifying released phosphate from fully pyrolyzed cell wall samples.39,51 Using phosphate analyses, estimates of teichoic acid by mass are then made by calculating the expected mass of the complete WTA unit associated with each WTA chain, assuming one phosphate per ribitol phosphate and three glycerol phosphate units as shown in Figure 1. The NMR estimate was within the error of the estimate of that from our phosphate analysis (Figure S1), wherein the molecular formula for WTA in the isolated cell wall (as in Figure 1) is C544 H1084N42O508P44. This value is also consistent with some previous reports of WTA content in S. aureus. Yet, using 13C CPMAS NMR, one can immediately evaluate the composition of the entire cell wall preparation and observe any obvious alterations in chemical composition, such as altered acetylation, which could be indicative of modifications to PG and/or WTA. We next sought to extend the NMR approach to monitoring PG and WTA in intact cells.

Specific PG and TA carbon signatures report on composition in intact bacterial cells

The cell wall of S. aureus accounts for 15–25% the mass of the cell wall, depending on the stage of growth and cell-wall thickness.31 Given the distinctive composition of the cell wall compared to other cellular components, cell-wall-specific NMR peaks can be detected within a whole-cell NMR spectrum, even without selective isotopic labeling. Most of the anomeric carbon peak intensity at 100 ppm, for example, is attributed generally to the bacterial cell wall as confirmed by comparison with protoplast preparations and cells treated with cell-wall inhibiting antibiotics.42 We tested the ability of a whole cell NMR approach to differentially detect and compare the relative contributions of WTA versus PG in whole cell samples without the need for cell-wall isolations.

We compared 13C CPMAS spectra of wild-type S. aureus and tarO mutant cells, lacking WTA (Figure 3). Compared to the whole cell 13C spectrum of wild-type cells, the tarO mutant exhibited a reduction in the polysaccharide region (60–90 ppm). The reduction is most prominent near 69 ppm, the ribitol region identified in the isolated WTA sample above (Fig 3). LTA glycerol carbons would generally contribute to this spectral region, but should peak near 74 ppm. The anomeric carbon peak intensity is slightly greater for the tarO mutant, possibly indicative of more PG, which would parallel observations of aberrant cell-wall division and accumulated cell wall in MW2ΔtarO.12 This will be supported below by 15N measurements. Thus, we use the anomeric and ribitol carbon peaks to first monitor and attempt to gauge PG and WTA compositional status, respectively, in intact cells.

Figure 3. 13C CPMAS spectra of intact S. aureus cells.

13C CPMAS of wild-type (black) and tarO mutant (green) whole cells, both harvested at OD600 1.0 (left). 13C CPMAS of whole cells at OD600 1.0 and 4.0 (right). Spectra were acquired with 32,768 scans.

Using these 13C spectral signatures, we made a new observation regarding the balance of PG and WTA as a function of growth state. For cells harvested during exponential phase (OD 0.5, 1.0), the intensity of the anomeric carbon was of similar height and area to those of aromatic carbons associated with ribosomal RNA and aromatic amino acid residues at 129 and 158 ppm.52 For cells harvested from the stationary phase (OD 2.0 and OD 4.0), the anomeric peak intensity increased (Figures 3 and S3). This observation is consistent with our previous TEM analysis, showing cell wall thickening, and NMR measurements in isolated cell walls using specific isotopic lysine labeling.31 However, an opposite trend was observed for the ribitol peaks: as cells reached stationary phase, the spectral area associated with teichoic acid decreased relative to the anomeric carbons. Thus, 13C NMR analysis suggested that cells harvested at OD 4 have cell walls with a higher PG:WTA ratio than cells harvested at OD 1.

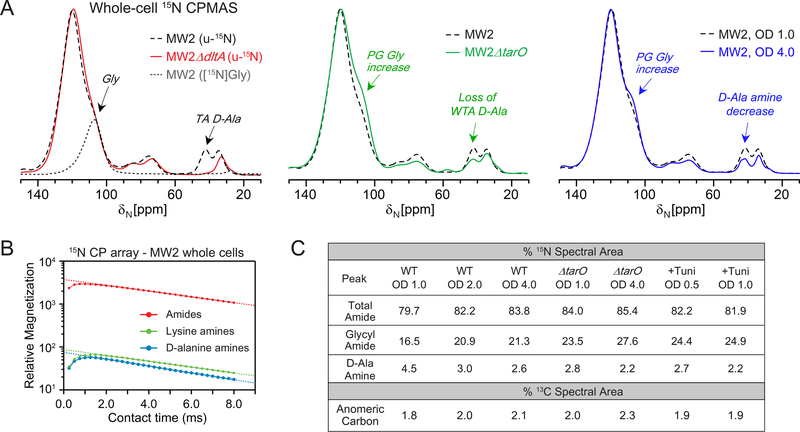

The anomeric carbon peak in each spectrum is shift resolved from other carbon types. Thus, the relative area of the anomeric peak can be compared across spectra to quantify the spectral differences. This is not intended to serve as an absolute determination of PG-specific anomeric carbons, but a way to quantify the observed spectral features across many samples. One can compare relative peak areas in different ways, depending on other possible hallmark features of interest, and presenting the relative spectral area compared to the total integrated area is one of the most straightforward ways to compare individual spectral contributions across sample. These comparisons for all the samples are tabulated at the bottom of Figure 4, with full spectra in Figure S3, together with the 15N analyses as described next.

Figure 4. 15N CPMAS spectra of S. aureus whole cells.

(A) 15N CPMAS spectral comparisons of MW2 (black) with MW2ΔdltA (red), and MW2 ΔtarO whole cells, all harvested at OD 1.0, and MW2 cells harvested at OD 4.0 (blue). A sample labeled selectively with only [15N]glycine (dashed grey) shows the specific chemical shift contributions of the glycyl amides, abundant in the cell wall (left panel). All spectra are scaled to the amide peak and were acquired with 32,768 scans. (B) CP array experiments were performed to examine the 1H-15N CP buildup and decay, yielding similar slopes for lines extrapolated from the long contact times for amide and D-Ala amine nitrogens. (C) The percent nitrogen spectral area is tabulated for total amides, glycyl amides, and D-Ala amines. The percent carbon spectral area is tabulated for the resolved anomeric carbon peak in each spectrum.

PG and WTA 15N signatures in whole-cell spectra

In the whole cell NMR approach, the 13C signatures described above are not used in isolation and are incorporated and framed together with evaluation of 15N spectra obtained from uniformly 15N-labeled cells in which all nitrogens in cells are labeled. The nitrogen pools of whole cells are mostly attributed to proteins and nucleic acids (Figure 4). The combined amides (100–120 ppm) dominate the spectrum. Other peaks are ascribed to nucleic acids and protein side chains (70–90 ppm), and amines from components including lysine residues (34 ppm). The peak at 42 ppm has been ascribed as having contributions from the D-Ala of teichoic acids.43 We confirmed this assignment and demonstrated here that the 42-ppm peak is entirely due to teichoic acid D-Ala by comparison with the whole-cell NMR spectrum of a dltA mutant, which lacks the dltA gene responsible for the D-alanylation of both wall and lipoteichoic acids.53 In the dltA mutant, the 42-ppm signal was abolished (Fig 4). We examined this peak intensity in the tarO mutant, which cannot synthesize any WTA but can still synthesize D-alanylated LTA. The D-Ala amine peak intensity decreased compared with wild-type cells, wherein the remaining peak intensity in MW2ΔtarO is ascribed specifically to LTA D-alanylation. Additional characterization of amine peak contributions was performed using cells labeled selectively with either D-[15N]Ala or L-[ε−15N]Lys and confirmed the distinct chemical shifts for alanyl and lysyl amines in whole cells (Figure S4). Previous work with selective lysine labeling and CPMAS and REDOR detection, with CPMAS results recapitulated here in Figure S3, documented the specificity of lysyl amine labeling (with no scrambling in SASM nutrient medium) and established that labeling efficiency of lysine is approximately 95% with only 5% dilution by endogenous lysine production.34 D-Ala and L-Ala selective labeling have also been extensively employed and characterized.54

Inspection of 15N CPMAS spectra of cells harvested during exponential versus stationary phase revealed a decrease in the D-Ala amine nitrogen to accompany the reduced 13C peak intensity in the ribitol-associated carbon region in Figure 3, together indicative of an overall reduction in the percent of teichoic acid in the sample. Moreover, in MW2ΔtarO, the observed D-Ala amine peak can only be due to LTA, since it lacks WTA, and this D-Ala amine peak decreased in relative intensity for cells harvested in stationary phase at OD 4.0. Thus, LTA D-alanylation was reduced in the MW2ΔtarO cells harvested at OD 4.0 with respect to PG content. Together with the reduction in the sugar carbons in the corresponding 13C whole-cell spectrum for the OD 4.0 MW2ΔtarO cells, this suggests that LTA levels are reduced. If no reduction were observed in the 13C spectrum, then such a result would point specifically to a reduction just in D-alanylation of teichoic acids rather than a decrease in total production. Thus, we distinguish between PG- and WTA-specific cell-wall assembly alterations.

Changes in the 15N glycyl amide region also revealed compositional changes in PG that support the 13C NMR observations. The glycyl amide resonance is shifted upfield from other amides and centered at 106 ppm (Figure 4). We demonstrated this specific assignment and unique contribution in whole cells previously using frequency-selective REDOR, identifying these nitrogens as coupled to glycyl α-carbons.42 We include here an independent way to highlight this assignment, providing a spectral overlay of whole cells grown in specific [15N]Gly-labeled medium.

The glycyl amide 15N shoulder increased in area for cells harvested in the stationary phase at OD 2 and 4, consistent with an increase in PG production and cell-wall thickening as suggested by the increase in the anomeric 13C carbon peak in Figure 3. Thus, the combined carbon and nitrogen NMR spectra provide orthogonal measurements to identify an increase in peptidoglycan and a concomitant decrease in teichoic acid as bacteria slow down metabolically and enter stationary phase. We also examined the 15N spectral area quantitatively to compare relative contributions from the distinct chemical shift regions present in the 15N spectrum to enable more facile comparisons among many samples. We obtained spectra as a function of CP time to generate CP buildup and decay curves for individual peaks to permit absolute quantitative intensity comparisons of the broad amide nitrogen peak and the D-Ala amine peaks, wherein the quantitative intensity is calculated from the y-intercept (corresponding to zero contact time) of a line fit to the decay curve to extract the maximum magnetization through CP transfer without relaxation.55 A total of 32 spectra were obtained and the 15N peaks exhibited highly similar CP buildup and decay curves (Figure 4 and Figure S5). This is not required for quantification, but is an observation that suggests the overall collection of the 1H spins behaves as a homogenous spin system available for 1H-15N CP. The quantitative peak area percentages (percentage of each peak of the total integrated spectral area) are tabulated in Figure 4C. The glycyl amide shoulder intensity was extrapolated by fitting the region directly with the spectrum of [15N]Gly-labeled cells (Figure S2), noting that PG pentaglycyl bridge is a major contributor to this region as evidenced by the major diminution in intensity in protoplast preparations42 (also included in Figure 4C). These spectral parameters provide a way to quantitatively compare spectral intensities and differences among many samples and NMR spectra. Other specific peak ratios can be obtained and could be valuable for comparing changes between two very specific nuclei in a sample. The 15N CPMAS changes were consistent with the 13C observations reported above. Specifically, the MW2 cells harvested in stationary phase at OD 4.0 exhibit increased amide nitrogen intensity, specifically glycyl amide, consistent with increased PG production and consistent with the increase in the anomeric carbon intensity in the 13C spectrum in Figure 3. The MW2 cells harvested at OD 4.0 also exhibit decreased D-Ala amine intensity, indicating reduced TA production per whole cell sample and is consistent with the intensity reduction associated with ribitol carbons in Figure 3.

These changes are similar to those observed when comparing wild-type MW2 and MW2ΔtarO cells that contain peptidoglycan and LTA, but lack WTA. In addition, MW2ΔtarO cells harvested at OD 4.0, as compared to OD 1.0, resulted in an amide (PG) increase and TA (amine) decrease. Thus, the PG-to-LTA mass ratio is greater for cells grown to OD 4.0, also consistent with increased PG production in stationary phase cells. CP array data for the uniformly 15N-labeled MW2ΔtarO cells are additionally provided in Figure S4D. Thus, a full NMR spectrum reflects the balance of all carbons in the cell and we have identified salient signatures that can be used to evaluate cell wall and cellular changes across samples.

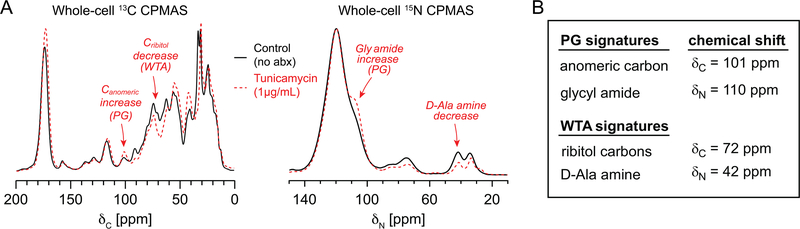

The influence of tunicamycin by whole-cell NMR

Through the above experiments, we demonstrated the ability to evaluate PG and WTA content in whole cells. The anomeric carbon and the glycyl amide nitrogens report on PG levels in whole cells, while the ribitol carbons and D-Ala amines report on teichoic acid levels (WTA plus LTA). We used these four signatures to examine the influence of tunicamycin by whole-cell 13C and 15N NMR (Figure 5). Tunicamycin is a compound known to inhibit teichoic acid synthesis and was also reported to influence enzymatic production of PG through in vitro enzymatic assays.13,56 We prepared our samples using a dose of compound of 1 μg/mL, similar to concentrations used to inhibit teichoic acid synthesis53 and introduced tunicamycin at the time of inoculation. 15N CPMAS results with tunicamycin-treated cells were comparable to the changes seen in the MW2ΔtarO cells (decreased D-Ala amine and increased glycyl amide shoulder). As noted above, a D-Ala amine decrease could simply be due to decreased D-alanylation of WTA or of LTA and overall conclusions must include consideration of the 13C whole-cell spectra. As observed in the 13C spectrum, tunicamycin resulted in a reduction of peak intensities associated with ribitol carbons (Figure 5A). This is consistent with inhibition of WTA. At the same time, the anomeric carbon and glycyl amide nitrogen levels associated with peptidoglycan increased relative to the control (Figure 5A). These effects were observed for cells harvested at both OD 0.5 and OD 1.0 after treatment with tunicamycin (Figure S4C), conditions that are similar to previous studies.13,53,56 An increase in peptidoglycan is consistent with aberrant and uncontrolled cell wall division when teichoic acid synthesis is inhibited, similar to that observed in the tarO mutant.12

Figure 5. Whole-cell NMR spectra of tunicamycin-treated S. aureus.

(A) The 13C CPMAS spectrum of cells treated with 1 μg/mL of tunicamycin revealed reduced intensity where ribitol phosphate carbons contribute and an increase in the anomeric carbon peak, ascribed primarily to PG. The 15N CPMAS spectrum of the same tunicamycin-treated sample exhibits an increased glycyl amide shoulder, supporting a relative increase in PG. The decrease in D-Ala amine nitrogen is consistent with a decrease in WTA. (B) 13C and 15N spectral signatures have resulted from examining intact cell walls and purified PG and WTA as well as the whole-cell NMR spectra comparing the influence of growth state and tunicamycin treatment.

Discussion

Solid-state NMR efforts to characterize bacterial cell walls and the modes of action of antibiotics have been uniquely valuable in dissecting the atomic and molecular details of antibiotics such as oritavancin and analogues, whose modes of action were not clear from biochemical experiments alone.35,57 Through a comparison of isolated cell walls and purified PG and WTA, we have developed an NMR approach to specifically identify and compare PG and WTA content in isolated cell walls and in intact whole cells. In the former case of isolated cell walls, we can estimate the PG:WTA ratio using the 13C CPMAS spectrum of the isolated cell walls.

As a complex, heterogeneous and insoluble polymer, there is no other method that provides this PG:WTA estimation in intact, undigested cell walls. Furthermore, the most facile analysis of teichoic acid for quantitative purposes is performed through hydrolysis and phosphate quantification, but does not itself provide any other information about composition. An extensive protocol of chemical digestions and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry could be used to analyze composition, but is time consuming and subject to the inability to completely digest PG. We work to address challenges in understanding antibiotic modes of action, for example, where intact cell wall and whole-cell NMR analyses are needed in mode-of-action determinations and resolving ambiguities from biochemical data. Some strategies have employed selective isotopic labeling strategies, often using pairs of individually labeled amino acids.31,35,37 However, recently, we have focused on developing approaches that could identify specific compositional information in unlabeled samples with natural abundance 13CNMR analysis or uniform (non-selective) labeling of samples for 15N NMR examinations. Natural abundance 13CNMR approaches are attractive as bacteria could be grown in complex medium or could be analyzed after being removed from a host setting or other complex environment.

Moreover, teichoic acids are difficult molecules to study in the context of whole cells. Their abundance can be estimated through indirect measurements of the phosphate content of cell walls;47 crude measurements of dry weight;8 or by quantifying GlcNAc incorporation with radiometry or D-alanylation through colorimetric assays.16 Yet, in all cases, cellular digestions are required that could be incomplete or associated with cellular debris. Solid-state NMR allows for the determination of the composition of the cell walls through direct observation of the combined sum of the carbon chemical shifts present in a cell-wall sample, providing additional inspection of the sample’s entire chemical composition and other potential compositional changes. The fitting of the two individual PG and WTA spectra to the cell wall spectrum yields the quantitative estimate for the PG:TA carbon mass ratio. Doing so, we estimated that about 22% of the carbon mass of cell walls is due to wall teichoic acids for these cells, noting that the three samples (cell walls, PG and WTA) were isolated from cells harvested at OD 4.0 from growth in TSB nutrient medium. We also observed enhanced acetylation for the purified PG isolated from cells that cannot produce TA. This analysis can be performed on isolated cell walls from samples harvested from different growth states or as a function of growth variables, such as the introduction of inhibitors, to quantify the PG:WTA carbon mass ratio in the cell wall. Importantly, whole-cell spectral changes additionally corroborated observations made from isolated cell walls and can be used to compare large sample sets with the ease of just whole-cell centrifugation and lyophilization for sample preparation, followed by 13C and, ideally, 15N CPMAS analysis. More detailed analysis for important sample comparisons would then be performed on isolated cell wall samples.

Finally, determining whether a compound interferes with PG and/or teichoic acid synthesis is complicated using biochemical analyses alone. Here, we have presented a holistic, solid-state NMR approach to examine intact S. aureus cells to infer whether PG and/or WTA levels are reduced as cell wall synthesis is inhibited. These analyses would accompany more specific cell-wall NMR studies and could be coupled to specific enzymatic analyses or digestion experiments or additional NMR experiments using selective labeling that quantify specific bond densities, e.g. crosslinks. A unique power of solid-state NMR is the ability to quantify chemical composition – to account for the combinations of all carbon types or nitrogen types in samples as complex as whole cells - and also to measure distances and map structures. As shown with the comparison of treatment with the inhibitor tunicamycin, whole-cell NMR provides an evaluation of the carbon and nitrogen status in intact cells, with the ability to identify alterations involving PG and WTA given their unique carbon and nitrogen composition as compared to most other cellular constituents (Figure 5B). A whole-sample accounting or framework will be valuable in diverse studies involving changes to bacterial cell composition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Suzanne Walker for providing S. aureus MW2, MW2ΔdltA and MW2ΔtarO strains. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM117278.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Chemical quantification of inorganic phosphate in cell walls and teichoic acids, quantification of peaks in whole cell CPMAS spectra, 13C and 15N CPMAS spectra of whole cells under different growth conditions, 15N CPMAS of whole cells labeled with L-[ε−15N]lysine and D-[15N]alanine.

References

- (1).Foster TJ FEMS microbiology reviews 2017, 41, 430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lovering AL; Safadi SS; Strynadka NC Annual review of biochemistry 2012, 81, 451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Egan AJ; Biboy J; van’t Veer I; Breukink E; Vollmer W Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 2015, 370: 20150031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sham LT; Butler EK; Lebar MD; Kahne D; Bernhardt TG; Ruiz N Science 2014, 345, 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhao H; Patel V; Helmann JD; Dorr T Molecular microbiology 2017, 106, 847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Schaefer K; Matano LM; Qiao Y; Kahne D; Walker S Nature chemical biology 2017, 13, 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Weidenmaier C; Kokai-Kun JF; Kristian SA; Chanturiya T; Kalbacher H; Gross M; Nicholson G; Neumeister B; Mond JJ; Peschel A Nature medicine 2004, 10, 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bertsche U; Yang SJ; Kuehner D; Wanner S; Mishra NN; Roth T; Nega M; Schneider A; Mayer C; Grau T; Bayer AS; Weidenmaier C PLoS One 2013, 8, e67398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bayer AS; Schneider T; Sahl HG Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2013, 1277, 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gautam S; Kim T; Lester E; Deep D; Spiegel DA ACS chemical biology 2016, 11, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wang H; Gill CJ; Lee SH; Mann P; Zuck P; Meredith TC; Murgolo N; She X; Kales S; Liang L; Liu J; Wu J; Santa Maria J; Su J; Pan J; Hailey J; McGuinness D; Tan CM; Flattery A; Walker S; Black T; Roemer T Chemistry & biology 2013, 20, 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Campbell J; Singh AK; Santa Maria JP Jr.; Kim Y; Brown S; Swoboda JG; Mylonakis E; Wilkinson BJ; Walker S ACS chemical biology 2011, 6, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lee SH; Wang H; Labroli M; Koseoglu S; Zuck P; Mayhood T; Gill C; Mann P; Sher X; Ha S; Yang SW; Mandal M; Yang C; Liang L; Tan Z; Tawa P; Hou Y; Kuvelkar R; DeVito K; Wen X; Xiao J; Batchlett M; Balibar CJ; Liu J; Xiao J; Murgolo N; Garlisi CG; Sheth PR; Flattery A; Su J; Tan C; Roemer T Science translational medicine 2016, 8, 329ra32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Campbell J; Singh AK; Swoboda JG; Gilmore MS; Wilkinson BJ; Walker S Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2012, 56, 1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Brown S; Santa Maria JP Jr.; Walker S Annual review of microbiology 2013, 67, 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Brown S; Xia G; Luhachack LG; Campbell J; Meredith TC; Chen C; Winstel V; Gekeler C; Irazoqui JE; Peschel A; Walker S Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109, 18909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Schirner K; Stone LK; Walker S ACS chemical biology 2011, 6, 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Schaefer K; Owens TW; Kahne D; Walker S Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Reichmann NT; Cassona CP; Grundling A Microbiology (Reading, England) 2013, 159, 1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schneewind O; Missiakas D Journal of bacteriology 2014, 196, 1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Santa Maria JP Jr.; Sadaka A; Moussa SH; Brown S; Zhang YJ; Rubin EJ; Gilmore MS; Walker S Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kho K; Meredith TC Journal of bacteriology 2018. doi: 10.1128/JB.00017-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kahan FM; Kahan JS; Cassidy PJ; Kropp H Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1974, 235, 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kahne D; Leimkuhler C; Lu W; Walsh C Chemical reviews 2005, 105, 425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cho H; Uehara T; Bernhardt TG Cell 2014, 159, 1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ling LL; Schneider T; Peoples AJ; Spoering AL; Engels I; Conlon BP; Mueller A; Schaberle TF; Hughes DE; Epstein S; Jones M; Lazarides L; Steadman VA; Cohen DR; Felix CR; Fetterman KA; Millett WP; Nitti AG; Zullo AM; Chen C; Lewis K Nature 2015, 517, 455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fiers WD; Craighead M; Singh I ACS Infect Dis 2017, 3, 688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lee W; Schaefer K; Qiao Y; Srisuknimit V; Steinmetz H; Muller R; Kahne D; Walker S Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Qiao Y; Srisuknimit V; Rubino F; Schaefer K; Ruiz N; Walker S; Kahne D Nature chemical biology 2017, 13, 793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Glauner B Analytical biochemistry 1988, 172, 451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zhou X; Cegelski L Biochemistry 2012, 51, 8143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kuru E; Hughes HV; Brown PJ; Hall E; Tekkam S; Cava F; de Pedro MA; Brun YV; VanNieuwenhze MS Angewandte Chemie 2012, 51, 12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sugimoto A; Maeda A; Itto K; Arimoto H Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cegelski L; Kim SJ; Hing AW; Studelska DR; O’Connor RD; Mehta AK; Schaefer J Biochemistry 2002, 41, 13053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Cegelski L; Steuber D; Mehta AK; Kulp DW; Axelsen PH; Schaefer J Journal of molecular biology 2006, 357, 1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kim SJ; Chang J; Singh M Biochimica et biophysica acta 2015, 1848, 350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kim SJ; Singh M; Sharif S; Schaefer J Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Yang H; Singh M; Kim SJ; Schaefer J Biochimica et biophysica acta 2017, 1859, 2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bui NK; Eberhardt A; Vollmer D; Kern T; Bougault C; Tomasz A; Simorre JP; Vollmer W Analytical biochemistry 2012, 421, 657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kern T; Giffard M; Hediger S; Amoroso A; Giustini C; Bui NK; Joris B; Bougault C; Vollmer W; Simorre JP Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132, 10911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Berejnaia O; Wang H; Labroli M; Yang C; Gill C; Xiao J; Hesk D; DeJesus R; Su J; Tan CM; Sheth PR; Kavana M; McLaren DG Analytical biochemistry 2017, 518, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Nygaard R; Romaniuk JA; Rice DM; Cegelski L Biophysical journal 2015, 108, 1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Rice DM; Romaniuk JA; Cegelski L Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance 2015, 72, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lusk G; Gullion T Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance 2018, 91, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Schaefer JSEO Journal of the American Chemical Society 1975, 98, 1031. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chen P; Toribara T.t.;Warner H Analytical chemistry 1956, 28, 1756. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ames BN; Dubin DTJ biol. Chem 1960, 235, 769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Swoboda JG; Campbell J; Meredith TC; Walker S Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology 2010, 11, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Bera A; Biswas R; Herbert S; Kulauzovic E; Weidenmaier C; Peschel A; Gotz F Journal of bacteriology 2007, 189, 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bera A; Herbert S; Jakob A; Vollmer W; Gotz F Molecular microbiology 2005, 55, 778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Bertsche U; Weidenmaier C; Kuehner D; Yang SJ; Baur S; Wanner S; Francois P; Schrenzel J; Yeaman MR; Bayer AS Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2011, 55, 3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Nygaard R; Romaniuk JAH; Rice DM; Cegelski L The journal of physical chemistry. B 2017, 121, 9331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Pasquina L; Santa Maria JP Jr.; McKay Wood B; Moussa SH; Matano LM; Santiago M; Martin SE; Lee W; Meredith TC; Walker S Nature chemical biology 2016, 12, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Romaniuk JA; Cegelski L Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 2015, 370: 20150024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).McDowell LM; Schmidt A; Cohen ER; Studelska DR; Schaefer J Journal of molecular biology 1996, 256, 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hakulinen JK; Hering J; Branden G; Chen H; Snijder A; Ek M; Johansson P Nature chemical biology 2017, 13, 265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Kim SJ; Cegelski L; Preobrazhenskaya M; Schaefer J Biochemistry 2006, 45, 5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.