Abstract

Objective:

To compare the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) contraceptive effectiveness poster with a more patient-centered poster on factors affecting the likelihood of using effective contraceptives.

Methods:

The posters were tested in a randomized controlled trial. Women were eligible if they were aged 18–44, could speak and read English, were not pregnant or trying to conceive, and had engaged in vaginal intercourse in the past three months. An online survey administered through Amazon Mechanical Turk was used to collect baseline and immediate follow-up data on three primary outcomes: contraceptive knowledge (measured using the Contraceptive Knowledge Assessment), perceived pregnancy risk, and the effectiveness of the contraceptive the woman intended to use in the next year. Subgroup analyses were conducted in women with prior pregnancy scares, low numeracy, and no current contraceptive. Within and between group differences were compared for the two randomized groups.

Results:

From January 26 to February 13, 2018, 2930 people were screened and 990 randomized. For the primary outcomes, the only significant result was that the patient-centered poster produced a greater improvement in contraceptive knowledge than the CDC poster (p<0.001). Relative to baseline, both posters significantly improved contraceptive knowledge (CDC +3.6, patient-centered +6.4 percentage points, p<0.001) and a constructed score measuring the effectiveness of the contraceptive that women intended to use in the next year (CDC and patient-centered +3 percentage points, p<0.01). This is equivalent to 1 to 17 out of every 100 women who viewed a poster changing their intentions in favor of a more effective contraceptive.

Conclusion:

This study suggests that both posters educate women about contraception and may reduce unplanned pregnancy risk by improving contraceptive intentions. Of the three primary outcomes, the patient-centered poster performs significantly better than the CDC poster at increasing contraceptive knowledge.

Precis:

A patient-centered poster educated women about contraception more effectively.

Introduction

Increased contraceptive knowledge is associated with reduced risk of unplanned pregnancy, by more consistent use of highly effective contraceptives.1 However, overall contraceptive knowledge among U.S. women is low; at least half underestimate the effectiveness of contraceptives for pregnancy prevention.1–4 Decision aids like posters are one tool that could be used to educate women about contraception; a Cochrane review found that decision aids like posters could increase knowledge, help patients make decisions, and help them experience less conflict about those decisions.5

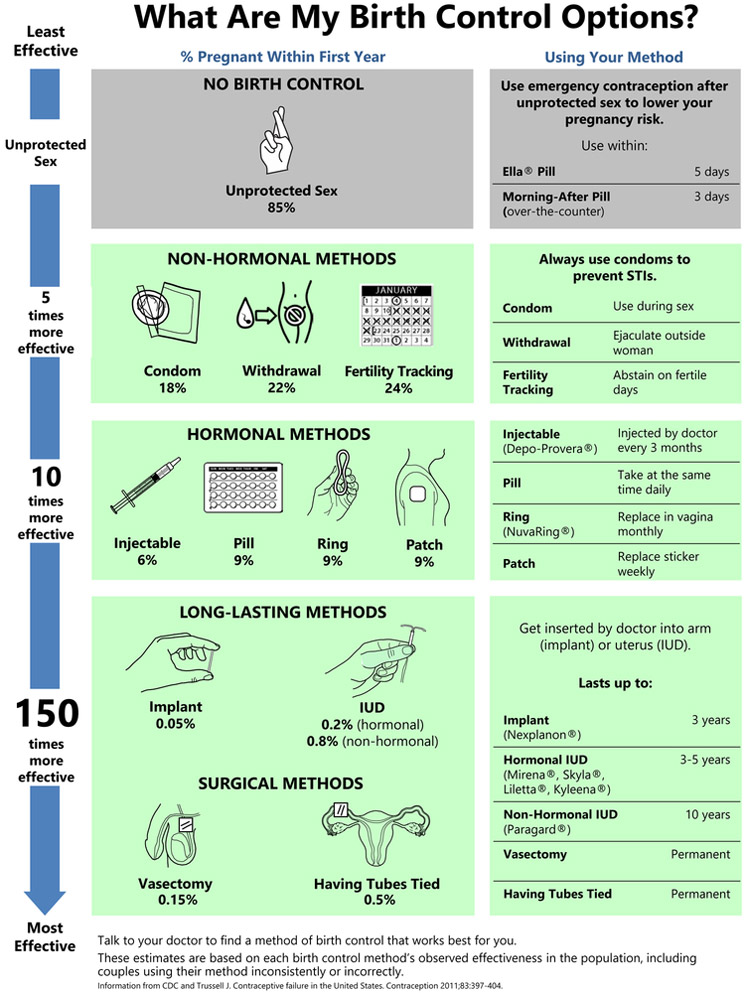

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that clinicians educate patients about contraceptive effectiveness and suggests their own contraceptive effectiveness poster as a potential tool.6 However, the CDC’s poster may not improve knowledge of the risk of pregnancy with unprotected sex, which is an important risk factor for inconsistent or non-use of contraceptives 3, 7, 8, because it does not include this information. Furthermore, the CDC poster’s design may be difficult to interpret for women with low health literacy or numeracy (i.e., facility with mathematics). The Institute of Medicine has declared designing educational materials for low health-literacy and numeracy populations a key public health priority.9

We designed a patient-centered poster that is appropriate for women with low numeracy that includes information about the risk of pregnancy with unprotected sex. Our main hypotheses are that women who view the patient-centered poster will immediately show greater increases in their contraceptive knowledge, greater accuracy in their perceived pregnancy risk, and greater effectiveness in their contraceptive intentions than women who view the CDC poster.

Methods

Our intervention compared exposure to either the CDC10 or the patient-centered (Figure 1) poster for as long as desired, with a minimum of one minute (average: 1.96 minutes for CDC, 1.79 minutes for patient-centered). The patient-centered poster was developed through cognitive interviews with 26 women aged 18–44 living in North Carolina who spoke and read English and had ever had sex.11 In that study, the final version of the patient-centered poster was preferred over the CDC poster by women overall based on its ease of comprehension, relevance to their decision-making needs, and visual appeal.

Figure 1:

The patient-centered contraceptive effectiveness poster. Data from Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011; 83:397–404 and modified with permission from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effectiveness of contraceptive methods. 2018; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/index.htm. Use of the material does not imply an endorsement by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or Health and Human Services (HHS) of any particular organization, service, or product, and that any views expressed in the book do not necessarily represent the views of CDC or HHS. Portions of the figure are reprinted with permission from: World Health Organization. Family planning: a global handbook for providers (2011 update). Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44028. Retrieved October 11, 2018; and World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP), Knowledge for Health Project. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers (2018 update). Baltimore and Geneva: CCP and WHO, 2018.

For this study, we used Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to select a convenience sample of U.S. women aged 18–44 who spoke and read English, were not pregnant or trying to conceive, and who had engaged in vaginal intercourse with a man in the past three months. MTurk is an online service which allows individuals to post surveys to be completed online for a fee.12 Data from MTurk users have been found to be as reliable or more reliable than data from other sources: workers have been consistently found to be attentive, their answers to questions consistent, and their answers no more or less truthful than in high-quality probability samples of the general population.13

We first screened for eligibility using a short online survey, for which participants were reimbursed $0.05. Eligible participants were invited to complete the full study survey online and reimbursed $3.60 upon completion, equivalent to the federal minimum wage for their time. The survey was implemented in Qualtrics, which automatically randomized women to equal-sized groups. The baseline data collection, intervention implementation, and outcome assessment were all conducted within one survey and the researchers were blind to assignment. The study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (IRB number 17–2955).

This study measured change in the mean scores for three primary outcomes: contraceptive knowledge, effectiveness of most likely contraceptive intended in the next year, and accuracy of perceived pregnancy risk. We gathered baseline and follow-up measures for each of these outcomes immediately before and after the intervention.

Contraceptive knowledge was measured objectively using the 25-item Contraceptive Knowledge Assessment.14 This produced a score between 0 (0% correct) and 25 (100% correct). Our contraceptive knowledge outcome was the change in this score between baseline and follow-up.

“Effectiveness of most likely contraceptive” was operationalized using a woman’s intention to continue using her current contraceptive and the contraceptive she reported being most likely to switch to were she to change methods in the next year. We first asked women at both baseline and follow-up: “Do you intend to use the same birth control method(s) that you are currently using for the next year?” If the woman said she intended to keep her contraceptive(s), the effectiveness of the most effective method she used in the past three months was used as her most likely contraceptive. The effectiveness of contraceptives was scored using the following WHO-defined categories2: IUDs, implants, and sterilization were considered highly effective (score = 3, 0–1% annual failure rate); the pill, patch, ring, and injection were considered effective (2, 2–9% annual failure rate); condoms, withdrawal, fertility tracking, and other methods were considered less effective (1, 10–30% annual failure rate); and no method was its own category (0, 85% annual failure rate). If a woman said she did not intend to keep her current contraceptive, we used the effectiveness of the contraceptive she intended to use. We measured this with the question, “If you had to change to a new birth control method in the next year, which of the following methods would you consider using?” Participants selected each method they would consider and then ranked the selected methods from most to least likely method. Our “effectiveness of most likely contraceptive intended in next year” outcome was the difference between a woman’s score at baseline and follow-up.

Finally, accuracy of perceived pregnancy risk was assessed by comparing a woman’s current contraceptive to her perceived pregnancy risk. Perceived pregnancy risk was measured using the following question: “What is your chance of getting pregnant this year?” with possible responses being very high (score = 5, annual pregnancy risk >50%), high (4, risk 25–50%), moderate (3, risk 5–25%), low (2, risk 1–5%), and very low (1, risk ≤1%). We assessed the accuracy of perceived risk based on the most effective birth control method a woman used in the past three months. In accordance with the WHO categories2, for highly effective methods, we coded an accurate perception to be very low risk; for effective methods, an accurate perception was low or moderate risk; for less effective methods, an accurate perception was moderate or high risk; for no method, an accurate perception was very high risk. An accurate perception was assigned a score of 1 and an inaccurate perception, 0. Our accuracy in perceived pregnancy risk outcome was the change in this score between baseline and follow-up.

Baseline data were collected on factors that might influence these outcomes. We measured prospective pregnancy intentions with the question, “Are you currently trying to get pregnant or avoid pregnancy?” with the response options: trying to get pregnant, wouldn’t mind getting pregnant, wouldn’t mind avoiding pregnancy, trying to avoid pregnancy, and don’t know.15 We measured past pregnancy scares by asking: “Have you ever had a pregnancy scare; that is, thought you were pregnant when you didn’t want to be, but later discovered that you weren’t pregnant after all?” We measured numeracy using the Berlin single item numeracy scale.16 This scale has been tested and validated to show that people who answer this question correctly are in the top 50% of the population in numeracy.16 We measured whether there were any contraceptives the woman could not use due to health or safety reasons using two questions. First, we asked the yes or no question: “Are there any types of birth control that you cannot use for health or safety reasons?”. If the woman responded “Yes” to this question, she was asked the follow-up question: “If yes, which forms of birth control are you prevented from using? Mark all that apply.” Her options included all of the methods except withdrawal and no method. Data were also collected on the sexes of the woman’s past sex partners, whether she had ever seen the poster before, and whether there were any types of birth control the woman could not use for cost reasons. The following variables were measured using questions from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG): biological sex, age, whether the participant was pregnant or trying to conceive, sexual intercourse in the past three months, education, time since first sex, and marital status. Finally, the following variables were measured using questions from the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health): race and ethnicity (Wave V), income (Wave IV), relationship status (Wave IV), and health insurance type (Wave IV).

We first tested whether the demographic and other factors were balanced between our randomized groups using two-sample t-tests and likelihood-ratio tests as appropriate. We did not find any statistically significant imbalances for any of the variables. We conducted two-sample t-tests on the change in the mean score for each of our outcomes to test whether each poster improved the three primary outcomes relative to baseline and in comparison to the other poster. We used the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. Using the same methods, we also tested the hypotheses that the three pre-specified subgroups (low numeracy, pregnancy scares, and no birth control) had greater increases in their mean scores for the patient-centered poster versus the CDC poster. We chose these subgroups because the patient-centered poster was designed to appeal to the needs of these groups. Finally, because correct answers to some of the questions on the Contraceptive Knowledge Assessment were not given by either poster, we could determine the proportion of the change in contraceptive knowledge that was attributable to the posters. We did this by analyzing the change in contraceptive knowledge separately for questions that did and did not have the correct answer provided by either poster. All analyses were conducted in Stata (Stata SE 15, College Station, TX, US).

For our power calculations, we assumed an alpha of 1% and a power of 80%. For our final analysis sample of N=936, comparing the two posters we can detect a 3 percentage point difference in mean change in contraceptive knowledge (standard deviation of 0.1814), a 0.8 percentage point difference in accuracy of perceived pregnancy risk (standard deviation of 0.05), and a 6 percentage point difference in the mean change in effectiveness of most likely contraceptive (standard deviation of 0.3517).

Results

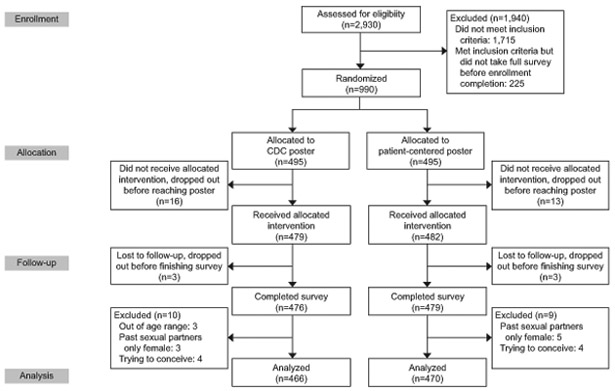

Participants were enrolled between January 26 and February 13, 2018 (Figure 2). Enrollment ended when our target enrollment goals were met.

Figure 2:

CONSORT flow diagram showing the progression to analysis sample by randomized poster group. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To evaluate the representativeness of our sample, we descriptively compare the distributions of baseline factors in our study sample to their distribution in the 2013–2015 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) survey, weighted to represent the national population of U.S. women eligible for our study (Table 1). We found no significant differences between the randomized groups on any of these baseline characteristics, but there are differences between the study population and the NSFG sample. The study sample appears to be more educated, more White, more middle-income, more likely to be cohabiting, less likely to be monogamous, more likely to have had female sexual partners, and less likely to be using effective contraceptives.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics for Full Sample, Randomized Poster Assignment Groups, and a Nationally Representative Survey

| Variable | CDC Poster (N=466)* |

Patient- Centered Poster (N = 470) |

Total (N = 936) |

NSFG 2013– 2015 (N = 3,021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, min, max) | 32 (18, 44) | 32 (18, 44) | 32 (18, 44) | 31.4 (18, 44) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | * (<1%) | * (<1%) | * (<1%) | 11% |

| High school graduate or GED | 138 (30%) | 130 (28%) | 268 (29%) | 34% |

| Two year college graduate | 82 (18%) | 94 (20%) | 176 (19%) | 19% |

| Four year college graduate | 177 (38%) | 184 (39%) | 361 (39%) | 23% |

| Graduate or professional school | 68 (15%) | 59 (13%) | 127 (14%) | 13% |

| Race or Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 352 (76%) | 350 (74%) | 702 (75%) | 62% |

| Black or African American | 44 (9%) | 35 (7%) | 79 (8%) | 13% |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 17 (4%) | 21 (4%) | 38 (4%) | 15% |

| Some other race | 28 (6%) | 33 (7%) | 61 (6%) | 11% |

| Multiple race | 25 (5%) | 31 (7%) | 56 (6%) | |

| Yearly Household Income | ||||

| <$9,999 | 16 (3%) | 11 (2%) | 17 (2%) | 10% |

| $10k to $14,999 | 21 (5%) | 18 (4%) | 39 (4%) | 7% |

| $15k to $19,999 | 19 (4%) | 20 (4%) | 39 (4%) | 5% |

| $20k to $24,999 | 22 (5%) | 31 (7%) | 53 (6%) | 4% |

| $25k to $29,999 | 33 (7%) | 30 (6%) | 63 (7%) | 6% |

| $30k to $39,999 | 53 (11%) | 55 (12%) | 108 (12%) | 11% |

| $40k to $49,999 | 62 (13%) | 69 (15%) | 131 (14%) | 8% |

| $50k to $74,999 | 101 (22%) | 118 (25%) | 219 (23%) | 19% |

| $75k to $99,999 | 72 (15%) | 67 (14%) | 139 (15%) | 10% |

| $100k> | 67 (15%) | 51 (11%) | 118 (13%) | 21% |

| Health Insurance Type | ||||

| No Insurance | 52 (11%) | 50 (11%) | 92 (10%) | 14% |

| Work | 140 (30%) | 140 (30%) | 280 (30%) | 65% |

| Spouse | 111 (24%) | 117 (25%) | 228 (24%) | |

| Parent | 31 (7%) | 30 (6%) | 61 (7%) | |

| Buy Private | 41 (9%) | 44 (9%) | 85 (9%) | |

| Medicaid | 77 (17%) | 83 (18%) | 160 (17%) | 17% |

| Other | 14 (3%) | * (<1%) | 30 (3%) | 3% |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Never married | 108 (23%) | 107 (23%) | 215 (23%) | 25% |

| Living with a partner | 116 (25%) | 126 (27%) | 242 (26%) | 19% |

| Married | 224 (48%) | 216 (46%) | 440 (47%) | 49% |

| Divorced | 14 (3%) | 18 (4%) | 32 (3%) | 4% |

| Separated | * (<1%) | * (<1%) | * (<1%) | 3% |

| Widowed | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0% |

| Number of Live Births | ||||

| 0 | 211 (45%) | 225 (48%) | 436 (47%) | 35% |

| 1 | 90 (19%) | 88 (19%) | 178 (19%) | 18% |

| 2 | 104 (22%) | 91 (19%) | 195 (21%) | 25% |

| 3 | 36 (8%) | 33 (7%) | 69 (7%) | 15% |

| 4 | 18 (4%) | 28 (6%) | 46 (5%) | 5% |

| 5+ | * (<1%) | * (<1%) | 12 (1%) | 2% |

| Pregnancy Scare | ||||

| Yes | 339 (73%) | 351 (75%) | 690 (74%) | |

| No | 126 (27%) | 118 (25%) | 244 (26%) | |

| Age at First Sex (mean, min, max) | 17.5 (7, 33) | 17.3 (11, 34) | 17.3 (7, 33) | 17.1 (3, 40) |

| Effectiveness of Most Effective Contraceptive Used in Past Three Months | ||||

| Highly Effective (IUD, Implant, etc.) | 72 (15%) | 81 (17%) | 153 (16%) | 37% |

| Effective (Pill, Patch, Ring, Injection) | 38 (8%) | 45 (10%) | 83 (9%) | 24% |

| Less Effective (Condom, etc.) | 258 (55%) | 246 (52%) | 504 (54%) | 29% |

| No Method | 98 (21%) | 96 (20%) | 194 (21%) | 10% |

| Cannot Use Some Contraceptives for Health Reasons | ||||

| Yes | 75 (16%) | 79 (17%) | 154 (16%) | |

| No | 391 (84%) | 391 (83%) | 782 (84%) | |

| Pregnancy Intentions | ||||

| Trying to get pregnant | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Wouldn’t mind getting pregnant | 36 (8%) | 44 (9%) | 80 (9%) | |

| Wouldn’t mind avoiding pregnancy | 33 (7%) | 23 (5%) | 56 (6%) | |

| Trying to avoid pregnancy | 389 (83%) | 396 (84%) | 785 (84%) | |

| Don’t know | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Previously Seen Poster | ||||

| Yes | 36 (8%) | 28 (6%) | 64 (7%) | |

| No | 415 (89%) | 438 (93%) | 853 (91%) | |

| Don’t know | * (<1%) | * (<1%) | 19 (2%) | |

| Numeracy | ||||

| Top 50% | 211 (45%) | 228 (49%) | 439 (47%) | |

| Bottom 50% | 255 (55%) | 240 (51%) | 495 (53%) |

Indicates cells with <10 observations

Table 2 shows descriptive results for our outcomes. Both groups started with a score of about 66% correct on the Contraceptive Knowledge Assessment. At baseline, the majority of women believed they were at very low risk of getting pregnant and only 23–24% of women had an accurate pregnancy risk perception. The majority of women (72%) using no method believed they had a low or very low chance of getting pregnant in the next year, despite the fact that 85 out of 100 sexually active non-users of contraceptives (or 164 of the 194 non-users of contraceptives in our study) will conceive over the course of a year.18 High percentages of women at baseline in both poster groups (64% CDC, 63% patient-centered) reported they were likely to use no or less effective contraceptives.

Table 2:

Pre- and Post-Exposure Descriptive Statistics for Outcomes

| Outcome Variable | CDC Poster (N=466) | Patient-Centered Poster (N = 470) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Mean Contraceptive Knowledge Score†

Range: 0 to 25 |

16.6 ± 3.76 | 17.5 ± 3.68 | 16.7 ± 3.63 | 18.3 ± 3.49 |

| 66.4% | 70% | 66.8% | 73% | |

| correct | correct | correct | correct | |

| Perceived Pregnancy Risk‡ | ||||

| Very High | * | * | * | * |

| High | * | 12 (3%) | 14 (3%) | 17 (4%) |

| Moderate | 72 (15%) | 65 (14%) | 50 (14%) | 50 (11%) |

| Low | 127 (27%) | 130 (28%) | 109 (23%) | 117 (25%) |

| Very Low | 252 (54%) | 252 (54%) | 293 (62%) | 283 (60%) |

| Accuracy of Perceived Pregnancy Risk Score†

Range: 0 to 1 |

0.24 ± 0.43 | 0.24 ± 0.43 | 0.23 ± 0.42 | 0.24 ± 0.43 |

| Most Effective Acceptable Method in Next Year‡ | ||||

| Highly Effective (IUD, etc.) | 148 (32%) | 199 (43%) | 151 (32%) | 193 (41%) |

| Effective (Pill, etc.) | 133 (29%) | 128 (27%) | 152 (32%) | 154 (33%) |

| Less Effective (Condom, etc.) | 160 (34%) | 124 (27%) | 142 (30%) | 106 (23%) |

| No Method | 25 (5%) | 15 (3%) | 25 (5%) | 17 (4%) |

| Most Likely Method Intended in Next Year‡ | ||||

| Highly Effective (IUD, etc.) | 106 (23%) | 130 (28%) | 105 (22%) | 120 (26%) |

| Effective (Pill, etc.) | 65 (14%) | 59 (13%) | 69 (15%) | 76 (16%) |

| Less Effective (Condom, etc.) | 222 (48%) | 205 (44%) | 220 (47%) | 203 (43%) |

| No Method | 73 (16%) | 72 (15%) | 76 (16%) | 71 (15%) |

| Mean Most Likely Method Intended in Next Year Score† | 1.44 ± 1.01 | 1.53 ± 1.06 | 1.43 ± 1.01 | 1.52 ± 1.03 |

| Range: 0 to 3 | ||||

Reporting Mean ± standard deviation

Reporting n (% of total for that poster)

Table 3 shows the results of our main hypothesis tests. Out of our three main hypotheses, we found that the patient-centered poster was only significantly more effective than the CDC poster at improving contraceptive knowledge (p<0.001). Both posters significantly improved contraceptive knowledge relative to baseline (p<0.001). The patient-centered poster improved contraceptive knowledge scores by 6.4 percentage points, or 1.6 additional correct questions, and the CDC poster improved scores by 3.6 percentage points, or 0.9 additional correct questions on average.

Table 3:

Results of T-Tests

| Outcome | Comparison Pre and Post for CDC Poster (N=466) |

Comparison Pre and Post for Patient- Centered Poster (N=470) |

Comparison Between Posters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome: Mean Change in Contraceptive Knowledge Score (99% Confidence Interval) Range: −25 to 25 |

0.90** (0.66–1.13) | 1.6** (1.31–1.90) | Patient-centered performed better** |

| Absolute Percentage Point Change | 3.6 | 6.4 | |

| Primary Outcome: Mean Accuracy of Perceived Pregnancy Risk Score (99% Confidence Interval) Range: −1 to 1 |

0 (−0.02–0.02) | 0.013 (−0.01–0.04) | Fail to reject the null hypothesis |

| Absolute Percentage Point Change | 0 | 1.3 | |

| Primary Outcome: Mean Change in Most Likely Method Score (99% Confidence Interval) Range: −3 to 3 |

0.09** (0.02–0.17) | 0.09* (0.01–0.17) | Fail to reject the null hypothesis |

| Absolute Percentage Point Change | 3 | 3 | |

| Positive Control: Mean Change in Questions Addressed by Posters (99% Confidence Interval) Range: −11 to 11 |

0.64** (0.50–0.78) | 1.31** (1.11–1.51) | Patient-centered performed better** |

| Absolute Percentage Point Change | 5.8 | 11.9 | |

| Change in % Correct | 68.5% to 74.4% | 68.6% to 80.5% | |

| Negative Control: Mean Change in Questions Not Addressed by Either Poster (99% Confidence Interval) Range: −14 to 14 |

0.26** (0.10–0.42) | 0.29** (0.12–0.47) | Fail to reject the null hypothesis |

| Absolute Percentage Point Change | 1.8 | 2.1 | |

| Change in % Correct | 64.9% to 66.6% | 65.5% to 67.6% |

p<0.01,

p<0.001 to account for multiple comparisons

The results for the analyses testing the change in contraceptive knowledge for questions that were and were not addressed by the posters can also be found in Table 3. We found a smaller increase in the mean percent correct for questions that were not addressed by either poster (1.8 percentage points for CDC and 2.1 percentage points for patient-centered) as compared to questions that were addressed by the posters (5.8 percentage points for CDC and 11.9 percentage points for the patient-centered poster). The magnitude of the change in the mean score for questions that were not addressed by either poster did not significantly differ between the posters.

While neither poster performed significantly better than the other at improving the score measuring the effectiveness of the most likely contraceptive intended in the next year, both posters improved this score compared to baseline by 3 percentage points (p<0.001) (Table 3);. This increase corresponds to between 1 and 17 out of 100 women increasing the effectiveness of their most likely contraceptive by one category (i.e., moving from no method to a less effective method).

The results in our subgroup analyses of women with pregnancy scares, low numeracy, or no current contraceptive were similar for all outcomes (results available from corresponding author). Participants reported no harms or unintended effects.

Discussion

Out of our three primary outcomes, we found that the patient-centered poster was only significantly more effective than the CDC poster at improving contraceptive knowledge. There were no statistically significant differences between the CDC and patient-centered posters’ effects on perceived risk of pregnancy and the score measuring effectiveness of the most likely contraceptive intended for the next year. However, relative to baseline we found that both the CDC and patient-centered posters significantly improved contraceptive knowledge and a score measuring effectiveness of the most likely contraceptive intended for the next year. We also found that the increases in contraceptive knowledge were attributable to the posters themselves.

A Cochrane review19 identified interventions that increased contraceptive knowledge, including two that tested educational tables2 or charts20. These two studies reported 14 to 37 percentage point increases, depending on the chart, for two questions asking participants to select the more effective contraceptive from a pair of methods.2, 20 However, compared to past studies that only assessed a small number of items tailored to the intervention19, ours comprehensively assessed the impact of these educational posters on contraceptive knowledge. Our study also found significant impacts on women’s intended contraceptive, which the Health Belief Model 21 suggests is likely to be more strongly associated with contraceptive behavior than contraceptive knowledge. Our results held in subgroups of participants who had low numeracy, prior pregnancy scares, and who do not use birth control, who may have greater challenges understanding information about contraception. We also saw these results despite participants only being exposed to the poster passively and for a very short period of time, similar to what they might experience if viewing the posters while waiting in a clinician’s office.

Our results are not generalizable to the general population of U.S. women because participants were recruited online using MTurk, meaning that in addition to our other inclusion criteria, participants also were by definition internet users. It is notable that our sample is more White, educated, and wealthy than the U.S. female population. However, the differences between our study sample and the NSFG sample are similar to the differences between Americans who use the internet and the general U.S. population.22 In the United States 99% of 18–29 year olds and 96% of 30–45 year olds use the internet.23 Our study sample also appears to be more knowledgeable about contraception than the general population14; because of this, it is possible that our findings underestimate the impact of posters on contraceptive knowledge. On the other hand, because our sample is better educated than the general US population, it is possible that they were more capable of learning from the posters, and our findings may overestimate the impact of posters on contraceptive knowledge. Finally, our study does not assess the impact of these posters on actual behaviors. Because of this limitation and the lack of previous studies using the Contraceptive Knowledge Assessment in a clinical population, we are unable to comment on the clinical significance of the 3 percentage point difference in the increase in contraceptive knowledge that we observed between the CDC and patient-centered posters. However, we did measure contraceptive intentions, which have been shown to be a good predictor of behavior.24, 25 The impact of these posters on actual contraceptive choices in clinical practice should be studied in future research.

Clinicians often struggle to educate their patients about the multitude of important health topics in the limited amount of time they have during appointments.26 This study tested two inexpensive tools to educate patients about contraception independently from a provider, and found that they effectively increase contraceptive knowledge and intentions to use more effective contraceptives. Using these posters in practice could allow doctors to spend more of their time answering questions about the patient’s specific contraceptive needs, rather than educating them on the basics of how each method works and how effective it is.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001111. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This research received support from the Population Research Infrastructure Program awarded to the Carolina Population Center (P2C HD050924) at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This work also received funding from the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine Small Grants Program Fund.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03372369.

References

- 1. Frost JJ, Lindberg LD, Finer LB. Young adults’ contraceptive knowledge, norms and attitudes: associations with risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012; 44:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner MJ, Dalebout S, Condon S, Dominik R, Trussell J. Understanding risk: A randomized controlled trial of communicating contraceptive effectiveness. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003; 102:709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaye K, Suellentrop K, Sloup C. The fog zone: How misperceptions, magical thinking, and ambivalence put young adults at risk for unplanned pregnancy Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biggs MA, Foster DG. Misunderstanding the risk of conception from unprotected and protected sex. Women’s health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 2013; 23:e47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col NF, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Library. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, Curtis K, Glass E, Godfrey E, et al. Providing quality family planning services. MMWR Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2014; 63:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polis CB, Zabin LS. Missed conceptions or misconceptions: Perceived infertility among unmarried young adults in the United States. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2012; 44:30–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg DL, Secura GM, Madden TE, Allsworth JE, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012; 206:479 e1–. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kindig DA, Panzer AM, Nielsen-Bohlman L. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prevention CfDCa. Effectiveness of Contraceptive Methods. CDC Website 20182017 [cited 2018]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson S, Barry M, Frerichs L, Wheeler SB, Halpern CT, Kaysin A, et al. Cognitive interviews to improve a patient-centered contraceptive effectiveness poster. Contraception. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paolacci G, Chandler J, Ipeirotis PG. Running experiments on amazon mechanical turk. Judgment and Decision making. 2010; 5:411–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandler J, Shapiro D. Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016; 12:53–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes MC, Ryan N, Saleh M, Winkel AF, Ades V. Contraceptive Knowledge Assessment: Validity and reliability of a novel contraceptive research tool. Contraception. 2017; 95:190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz EB, Lohr PA, Gold MA, Gerbert B. Prevalence and correlates of ambivalence towards pregnancy among nonpregnant women. Contraception. 2007; 75:305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cokely ET, Galesic M, Schulz E, Ghazal S, Garcia-Retamero R. Measuring risk literacy: The Berlin numeracy test. Judgment and Decision Making. 2012; 7:25. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonishak J, Kaye K, Swiader L. Impact of an online birth control support network on unintended pregnancy. Social Marketing Quarterly. 2015; 21:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trussell J Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011; 83:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez LM, Steiner M, Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Strategies for communicating contraceptive effectiveness. The Cochrane Library. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steiner MJ, Trussell J, Mehta N, Condon S, Subramaniam S, Bourne D. Communicating contraceptive effectiveness: A randomized controlled trial to inform a World Health Organization family planning handbook. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006; 195:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall KS. The Health Belief Model can guide modern contraceptive behavior research and practice. Journal of midwifery & women’s health. 2012; 57:74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillygus DS, Jackson N, Young M. Professional respondents in non-probability online panels. Online panel research: A data quality perspective. 2014:219–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Center PR. Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center Website2017 [updated January 12, 2017; cited 2017. April 21]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kothandapani V Validation of feeling, belief, and intention to act as three components of attitude and their contribution to prediction of contraceptive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1971; 19:321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim M-S, Hunter JE. Relationships among attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behavior: A meta-analysis of past research, part 2. Communication research. 1993; 20:331–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison I, Smith R. Hamster health care: time to stop running faster and redesign health care. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2000; 321:1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.