Abstract

Focused ultrasound (FUS) has been shown to increase the permeability of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) and its feasibility for opening the Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier (BSCB) has also been demonstrated in small animal models, with great potential to impact the treatment of spinal cord disorders. For clinical translation, challenges to transvertebral focusing of ultrasound energy to the human spinal canal, such as focal depth of field and standing wave formation, must be addressed. A dual aperture approach using multi-frequency and phase shift keying (PSK) strategies for achieving a controlled focus in human thoracic vertebrae was investigated through numerical simulations, and benchtop experiments in ex vivo human vertebrae. An ~85% reduction in focal depth of field was achieved compared to a single aperture approach at 564khz. Short burst (2-cycle) excitations in combination with PSK were found to suppress the formation of standing waves in ex vivo human thoracic vertebrae when focusing through the vertebral laminae. The results make an important contribution towards the development of a clinical scale approach for targeting ultrasound therapy to the spinal cord.

Keywords: Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier (BSCB), Dual aperture, Focused Ultrasound (FUS), Multi-frequency, Phase Shift Keying (PSK), Therapeutics

I. Introduction

THE vasculature in the Central Nervous System (CNS) differs from vasculature elsewhere in the body, due to the presence of barriers like the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) and the Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier (BSCB). These barriers serve an important role in maintaining a specialized and selective environment within the CNS. They are characterized by non-fenestrated endothelial cells (ecs) with tight junctions (tjs) between them and lead to the reduction of both transcellular and paracellular transport [1]. The BBB and BSCB pose significant challenges to conventional intravenous and oral methods of drug delivery to the brain and Spinal Cord (SC). It has been estimated that 100% of large molecule drugs (Molecular Weight > 500Da) and approximately 98% of small molecule drugs are unable to cross the BBB in therapeutically relevant quantities [2], [3]. Existing methods to circumvent these barriers have a range of disadvantages including invasiveness, difficultly achieving therapeutic concentrations, and non-targeted effects [4]–[6].

Focused Ultrasound (FUS), in conjunction with the intravenous administration of ultrasound contrast agents/microbubbles (mbs), has been shown to produce consistent, reproducible and reversible BBB Opening (BBBO) [7]. There have been hundreds of preclinical studies implementing FUS induced BBBO for the delivery of tracers or therapeutic agents, ranging in size from small molecule drugs [8]–[10] to cells [11], [12], to the brain. FUS induced BBBO has reached the stage of clinical trials for the delivery of chemotherapeutic doxorubicin to brain tumours [13], [14] and in Alzheimer’s patients without an administered drug (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02986932).

Despite the clinical promise of FUS induced BBBO, application to the BSCB has received limited attention. Wachsmuth et al. Demonstrated the feasibility of FUS induced BSCB Opening (BSCBO) in Wistar rats in 2009 [15]. The method has since been successfully exploited for non-invasive targeted gene delivery to the spinal cord in rats [16]. Payne et al. Have demonstrated successful BSCBO in rats without gross tissue damage. However, minor neurological impairment was observed in some subjects, indicating the need for refinement of FUS parameters [17]. The efficacy of this method for antibody delivery for the treatment of leptomenigeal metastases has also been demonstrated [18].

Although initial studies of FUS induced BSCBO in small animal models have been promising, the delivery of ultrasound energy within the complex environment of the human spine is a challenge that must be overcome for clinical translation. The submegahertz frequencies required to minimize the effects of attenuation and aberration as ultrasound propagates through a layer of bone [19] lead to long focal zones compared to the size of the target within the spinal canal (human thoracic spinal canal depth is typically less than 20mm [20]).

Long focal zones may lead to internal reflections and the formation of standing waves. Standing waves result in heterogeneous patterns of barrier opening, potential off-focus effects and difficulty predicting in situ pressures [21], all of which increase the risk of overexposing the tissue. Further, acoustic cavitation events are more likely in a stationary wave compared to a travelling wave [22], and bubbles can become trapped at antinodes [23]. Due to lower attenuation, submegahertz frequencies are more likely to result in standing waves in the skull cavity compared to higher frequencies [24]. Standing waves have been shown to contribute to high pressure off-focus effects leading to unwanted and unpredictable damage and heating in transcranial studies [25], [26]. The most convincing example is the TRUMBI clinical trial which employed trans-skull sonications at 300khz [27] and had to be prematurely ended due to the occurrence of symptomatic haemorrhage in five patients. Comprehensive simulations using TRUMBI parameters were later performed and showed a wide range of off-target effects linked to the generation of standing waves [26]. The use of multi-element large aperture arrays combined with geometric effects of the skull reduce the potential for standing waves during transcranial therapies [28]. However, such large apertures cannot be easily realized for the spinal geometry, particularly in the thoracic region where the lungs and ribs restrict treatment geometry to a dorsal approach. This has severe implications for the formation of standing waves when focusing within the spinal cavity.

To achieve a controlled focus in the spinal canal and avoid off-focus effects resulting from reflections at the bone interfaces, it is necessary to overcome challenges relating to focal depth of field and standing waves. Confocal, dual-frequency FUS can reduce the focal depth of field. Exploiting the interference between two confocal, ultrasound beams with an angular separation, θ = 120°, and a frequency difference, Δf = 30Hz, has been shown to reduce the focal depth of field by 78% at 837khz for cavitation based ablation in a rat brain [29]. The success of this approach for controlled, microbubble-mediated BBBO in rats has also been demonstrated at 274.3khz, with θ = 102° and Δf = 31Hz [30]. Although confocal monofrequency FUS can reduce the depth of field by increasing the effective aperture it results in large secondary lobes. By implementing a dual-frequency approach, with a burst length greater than the beat frequency, the focal region can be smoothed to generate a single main lobe [30]. Although confocal, dual-frequency ultrasound has been demonstrated to reduce the focal depth of field [29], the effect of parameters, such as the angular separation, pulse length and the frequency difference between the transducers, on the focal profile has not been fully reported.

There has been substantial research geared towards standing wave mitigation in ultrasound. The use of swept-frequency (chirp) waves has been shown to reduce the standing wave artefact in vibroacoustography [31] and in radiation force measurements [32]. It was later shown that using random frequency modulations was a superior technique for standing wave minimization, compared to linear chirps, within the human skull and a plastic cavity of parallel walls [33]. To overcome challenges related to the broadband requirements for producing modulated frequency therapy pulses, phase-shift keying (PSK) excitations were investigated for mitigating standing waves. It has been shown that random PSK is more effective than sequential PSK for this purpose [34]. These techniques all rely on breaking the coherence between incident and reflected waves whereby the interference between the two is complicated and the standing wave pattern is disrupted. The efficacy of these methods has been verified in large cavities, on the order of magnitude of the human skull. However, experiments in the rat skull have been less promising [35]. One method that has been successful at minimizing the effects of standing waves in the rat skull is the use of closely timed short burst excitations compared to more conventional quasi-continuous therapy pulses [35]. Further, rapid-short pulse (rasp) sequences have been shown to improve spatiotemporal uniformity of MB activity during FUS exposure [36], [37]. However, these short-pulse excitations have all been implemented at frequencies above a megahertz and have yet to be studied in small cavities at frequencies relevant to clinical scale sonications.

The goal of this study was to identify a method for simultaneously achieving a reduction in both focal depth of field and standing wave content for sonications in the human spinal canal. In this paper the effects of confocal, dual-frequency FUS and sonication parameters on focal depth of field are characterized, and methods for the mitigation of standing waves in a phantom and in ex-vivo human thoracic vertebrae are investigated. The results of this study and their implications for future work and the clinical application of FUS induced BSCBO are discussed.

II. Materials and Methods

A. Confocal, dual-frequency FUS

Numerical simulations:

Simulations were performed in k-Wave, which is an open source toolbox for the time domain simulation of acoustic waves in MATLAB and C++ [38]. Simulations were performed in 2-D and in a homogeneous medium with the acoustic properties of water. The water temperature was assumed to be 20°C, and the speed of sound, c, was determined using the built-in k-Wave function, speedsoundwater(). 20°C was chosen to be consistent with benchtop experiments, which were done at room temperature. The density of the medium, ρ, was assumed to be 998kg/m3 [39]. The effects of attenuation were not considered.

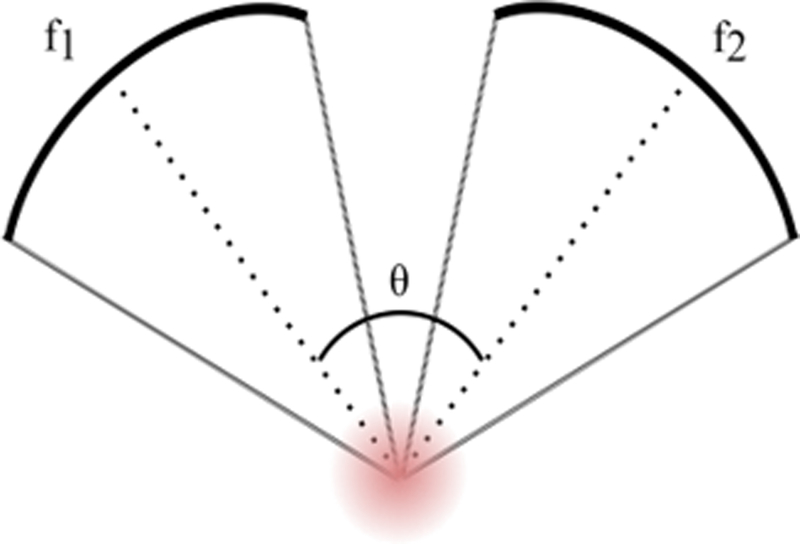

The parameters that were investigated numerically for their effects on confocal, dual-frequency FUS are outlined in Table I. Transducers were consistently defined with an aperture diameter of 5cm. A schematic diagram of the simulation layout is shown in Fig. 1. Each transducer was driven at a frequency offset from f by ±Δf/2. The focal depth of fields for single transducer cases were compared with confocal dual-frequency FUS. Numerical results were used to inform benchtop experiments.

TABLE I.

Parameters Investigated Numerically For Their Effect On Confocal, Dual-Frequency Fus

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-numbera | 1.2 | ||

| Frequency | f | kHz | 564 |

| Frequency Difference | Δf | kHz | 0:10:100 |

| Angular Separation | θ | ° | 60:10:120 |

| Number of cycles per pulse | N | cycles | 2,5,10:10:50 |

The F-number of a transducer is defined as the ratio of focal length to aperture diameter.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of simulation layout for investigating the effects of confocal, dual-frequency FUS on focal depth of field.

Benchtop experiments:

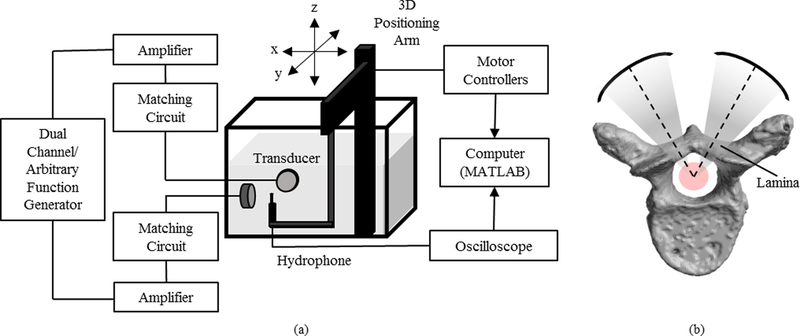

Parameters that showed promising results in simulations were investigated experimentally. A diagram illustrating the experimental set-up for investigating confocal, dual-frequency FUS is shown in Fig. 2(a). Ultrasound field measurements were made using a 0.5mm PVDF needle hydrophone (Precision Acoustics, Dorchester, UK). The hydrophone was navigated using a 3-D positioning arm (Velmex Inc., NY, USA) connected to a motor controller (RS-232, Velmex Inc., NY, USA), and mounted in a tank filled with deionized, degassed water.

Fig. 2.

(a) A diagram illustrating the experimental set-up for investigating the effects of confocal, dual-frequency FUS on focal depth of field. (b) A diagram showing the confocal, dual-frequency approach through the vertebral laminae.

In-house assembled, spherically-focused transducers (elements sourced from del Piezo Specialties, LLC, FL, USA) with a center frequency of 514 khz and F-number = 1.2 were used to generate the ultrasound. The transducers were matched to 50 Ω, 0° using external matching circuits and were driven using a dual-channel arbitrary/function generator (AFG 3052C, Tektronix, OR, USA) and 53db RF power amplifiers (NP-2519, NP Technologies Inc., ON, CA).

Time domain data from the hydrophone was displayed on a mixed domain oscilloscope (MDO 3014, Tektronix, OR, USA) and subsequently transferred to a PC, where it was stored and saved. Data was processed in MATLAB to visualize the temporal peak pressure distribution for the ultrasound field.

To ensure that the two transducers were confocal, the first transducer remained fixed, while the second transducer was mounted to a manual 3-D positioning stage for fine adjustment. The hydrophone was fixed aligned to the maximum pressure location of the first transducer. Subsequently, the hydrophone remained at the focus of the fixed transducer and the second transducer was adjusted until its maximum pressure location was aligned with that of the first transducer.

B. Standing wave mitigation

Focusing within a reflecting cavity using confocal, dual-frequency ultrasound was investigated in an acrylic tube phantom and in ex-vivo human thoracic vertebrae. Different pulse modifications in the time and frequency domains were evaluated for their potential to mitigate the formation of standing waves.

Numerical simulations:

The simulation medium was adjusted to include (a) a circular acrylic phantom of diameter 22mm and wall thickness 2mm (c = 2750m/s, ρ = 1190kg/m3 [40]), or (b) a homogeneous rendering of a slice through vertebrae obtained from CT data of degassed vertebral specimens (c = 2429m/s, ρ = 1900kg/m3 [19]). The values of c used for vertebral bone were based on the frequency dependent values reported for cortical skull bone in [19], under the assumption that measurements were performed at room temperature. The suspending medium remained with the acoustic properties of water. Ultrasound was focused through the vertebral laminae and the geometric foci of the transducers were aligned with the centre of the reflecting cavity (Fig. 2 (b)).

Simulations ignored the effects of shear mode propagation in vertebrae and assumed homogeneity. Results were used to inform benchtop experiments.

Benchtop experiments:

Benchtop experiments were adjusted to include (a) a cylindrical acrylic phantom of diameter 22mm, wall thickness 2mm and height 42mm, or (b) a degassed ex-vivo thoracic vertebra (T1, T3, T5, T7, T9, or T11). Vetebrae were degassed in a vacuum jar for a minimum of 2 hours prior to each experiment. Specimens were aligned in the scan tank so that the centre of the reflecting cavity roughly coincided with the maximum pressure location measured by the hydrophone. For benchtop experiments, standing waves were investigated first for the single aperture case, and then for the dual-aperture case.

Standing wave content was quantitatively evaluated using a newly developed metric, referred to here as the S-number, which considers the spatial frequency content along transducer axes. Spatial frequency spectra were determined by taking a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of a line along the transducer axis of the temporal maximum pressure distribution. Standing waves correspond to a critical spatial frequency, υcrit, which corresponds to half the wavelength (λ/2) of ultrasound used. The S-number is defined in equation 1.

| (1) |

where S is the S-number and ROI is the Region of Interest defined by the width of the peak at υcrit. This gives a measure of standing wave content relative to the pressure at the focus.

Linear chirp pulses, phase shift keying (PSK) and short burst excitations were evaluated for their potential to supress the formation of standing waves in thoracic vertebrae. Standing wave content was compared to a control case using an N = 30 cycles sinusoidal pulse (Fig. 3 (a)) to obtain a normalized S-number. N = 30 was chosen as the control pulse because at the frequencies of interest, it was long enough to allow the development of standing waves within the reflecting cavities, while being short enough allow for reasonable scan times and to avoid reflections from the rear wall of the scan tank during benchtop experiments.

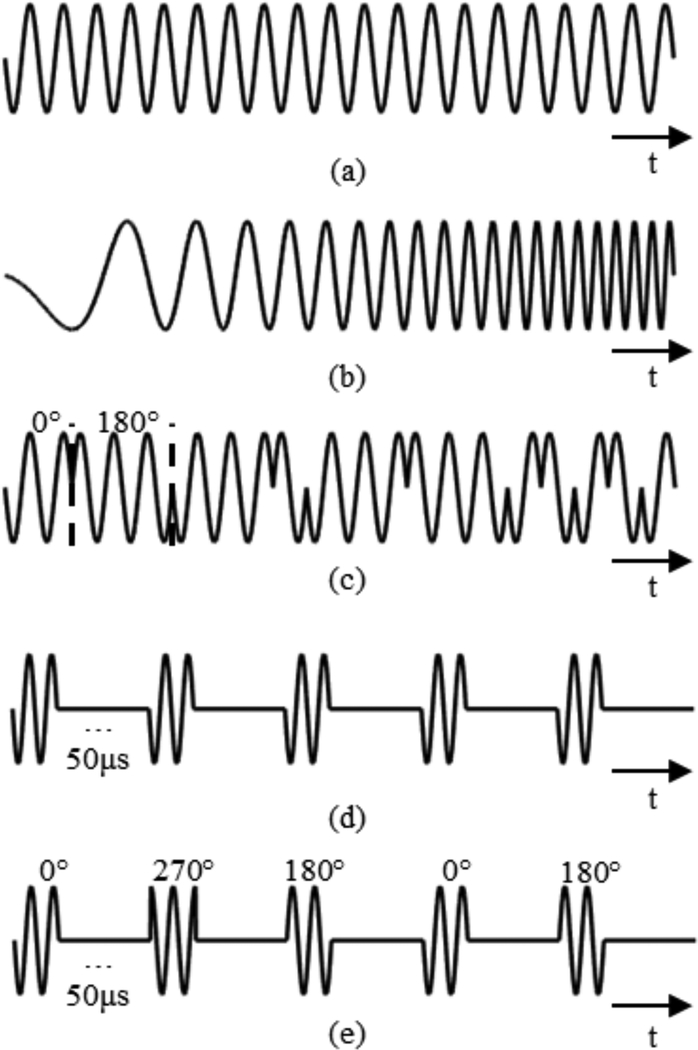

Fig. 3.

Plots showing examples of (a) the sinusoidal control pulse, (b) a linear chirp pulse, (c) random binary phase shift keying every cycle, (d) short burst (2-cycle) excitations, and (e) short burst excitations combined with random quadrature phase shift keying.

Linear chirp pulses:

A chirp bandwidth, W, was defined and the chirp was centred about the transducer driving frequency. Frequency was incremented linearly from a starting value, fstart, to an ending value, fend, such that |fend-fstart|=W. The chirp pulses used had an equivalent length to the control pulse and different chirp directions and values of W were investigated. An exaggerated example of a linear chirp pulse (W = 1khz) is shown in Fig. 3 (b).

Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK):

Random BPSK consisted of transmit pulses where the phase of the pulse was changed after a certain number of cycles, n. For BPSK the phases used were either 0° or 180°. At each interval, phase was assigned by a random variable. Different values of n were investigated. BPSK pulses used had an equivalent length to the control pulse. An example of BPSK (n = 1) is shown in Fig. 3 (c).

Quadrature Phase Shift Keying (QPSK):

Random QPSK pulses differed from BPSK pulses only with respect to the phases used. For QPSK 0°, 90°, 180° and 270° phase shifts were assigned randomly. QPSK pulses used had an equivalent length to the control pulse.

Short Burst Excitations:

Short, N=2, pulses with a pulse repetition period (PRP) of 50μs were used. An example of short burst excitations is shown in Fig. 3 (d).

Short Burst Excitations with random PSK:

Short, N=2, pulses with a pulse repetition period (PRP) of 50μs were used. At the start of each pulse, phase was randomly assigned. An example of short burst excitations combined with random QPSK is shown in Fig. 3 (e).

For benchtop experiments, pulses were generated in MATLAB and uploaded to the arbitrary/function generator.

S-numbers for modulated pulses were normalized to the control case to compare their levels of effectiveness. Pulses that showed promising results in simulations were investigated on the benchtop. Experimentally, pulses were first investigated for the case of a single transducer, and then for confocal transducers. Statistical significance of normalized S-numbers were determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Tukey test. Statistical significance was considered if there was a p-value < 0.05.

III. Results

A. Confocal, dual-frequency FUS

Numerical simulations:

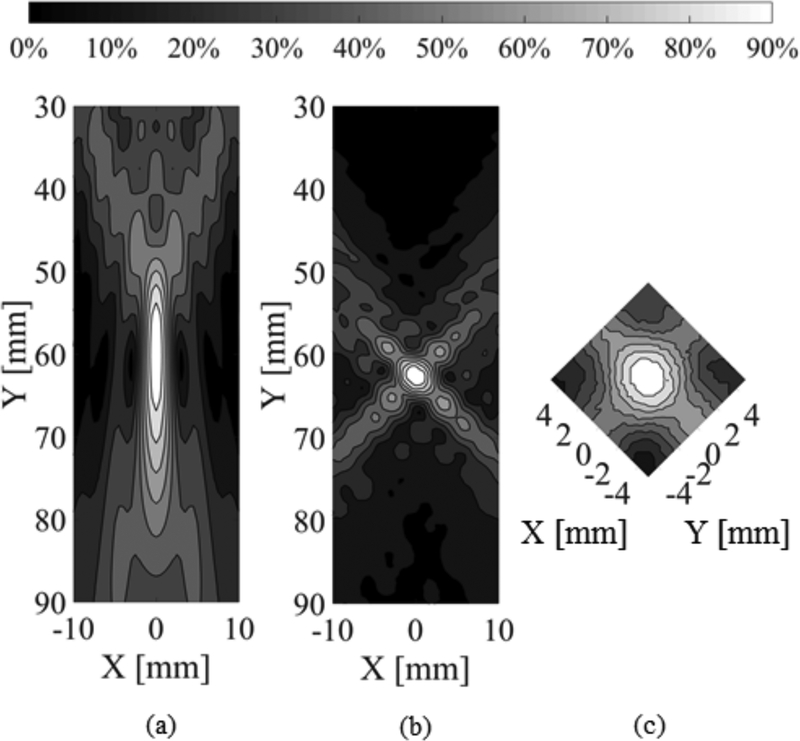

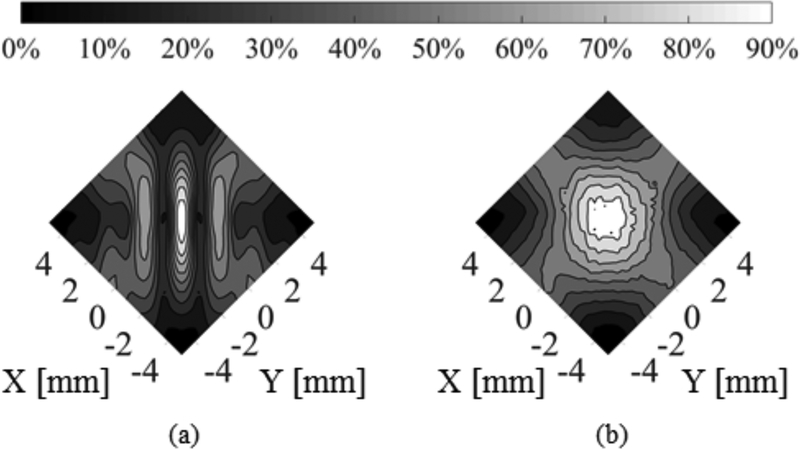

A comparison between a single transducer case and a confocal, dual-frequency case is shown in Fig. 4. Fig. 4 (a) shows a contour plot of the maximum pressure distribution for a single transducer with f = 564khz and a F-number of 1.2, driven with a 30-cycle pulse in water. Fig. 4 (b) shows a contour plot of the maximum pressure distribution for confocal transducers with f = 514khz and f = 614khz (Δf = 100khz), θ = 90°, driven with 30 cycle pulses in water.

Fig. 4.

(a) Contour plot of maximum pressure distribution for a simulation of a single transducer driven at 564kHz, with F-number of 1.2 (Transducer axis is parallel to the Y axis). (b) Contour plot of maximum pressure distribution for a simulation of confocal transducers driven at 514 and 614kHz, with F-number 1.2 and an angular separation of 90° (Transducer axes form a diagonal with plot axes). (c) Contour plots of experimental maximum pressure distribution for confocal transducers driven at 514 and 614 kHz in water, with F-number 1.2 and an angular separation of 90° (Transducer axes are parallel with plot axes).

Figs. 4(a) and (b) show that there is a decrease in the focal depth of field in the confocal, dual frequency case compared with the single transducer case. This reduction is due to the interference between the foci of the two transducers. Conventionally, the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), or the 50% contour, is used to denote the focal depth of field. Fig. 4 (b) shows that the 50% contour forms a cross where the two foci overlap. This superposition of foci is asymmetric because the two different frequencies result in slightly different focal dimensions. The pressure distribution tightens quickly, such that the 70% contour forms a more precise, ellipsoidal area. It is possible to actively control the peak pressures and FUS-induced BSCBO is a threshold effect [41]. Therefore, it should be possible to limit the therapeutic effect to within the 70% contour, or an even narrower region of the focus. Quantitatively, the focal depth of field for the single transducer case shown in Fig. 4 (a), as defined by the 70% contour is (24.5 ± 0.5) mm. In comparison, the focal depth of field for the confocal dual-frequency case shown in Fig. 4 (b) is (3.7 ± 0.5) mm. This corresponds to a reduction in the focal depth of field of approximately 85%.

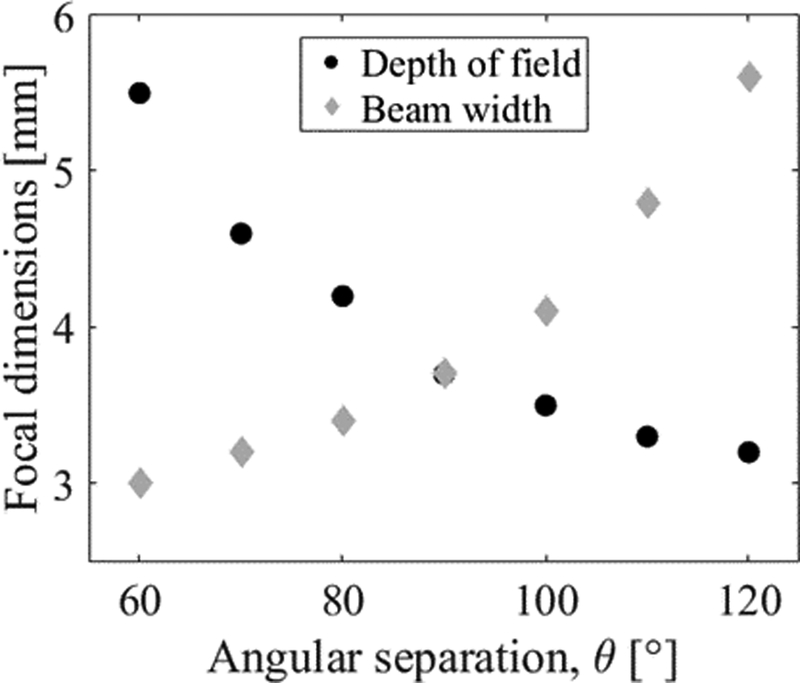

The effect of increasing or decreasing the angular separation, θ, is illustrated in Fig. 5. Although the larger values of θ result in the greatest reduction in depth of field, these large angles may not necessarily be achievable in practice due to the geometry of the vertebrae. Reducing θ to a more realistic 60° results in a 78% reduction in depth of field compared to the single transducer case.

Fig. 5.

A plot showing the relationship between angular separation, θ, and the 70% contour focal dimensions (depth of field and beam width). At θ = 90°, the depth of field and beam width are approximately equal.

Benchtop experiments:

Benchtop results agree with the simulations, showing that a focal spot precise enough to focus within the human spine can be achieved. Fig. 4 (c) shows the normalized maximum pressure distribution for confocal transducers driven at 514 and 614 khz in water with θ = 90° and N = 30. The focal depth of field as defined by the 70% contour is (4.21 ± 0.25) mm.

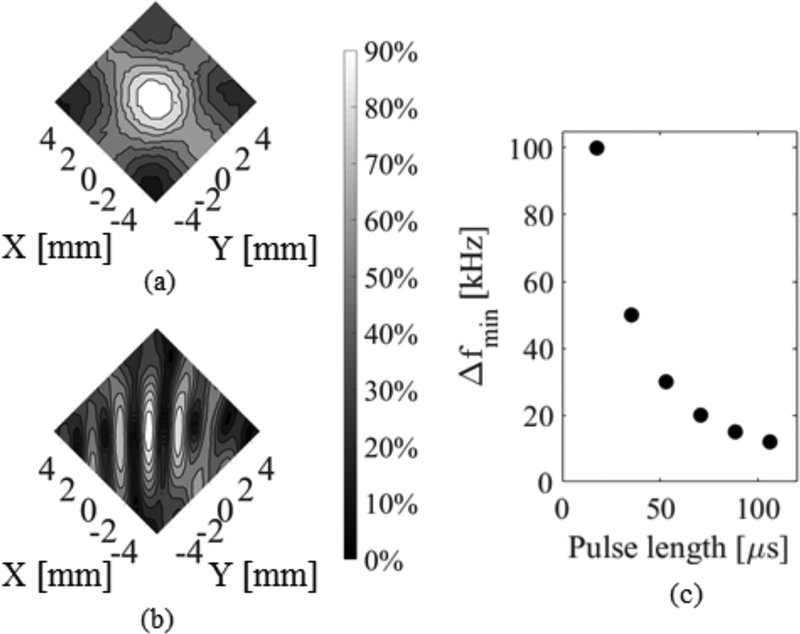

A frequency difference is required between the two transducers to avoid the formation of an interference pattern in the focal region due to the interaction of the two incident waves. Fig. 6 (b) shows the measured maximum pressure distributions for confocal transducers with Δf = 0 khz which contrasts the case shown in 5 (a) with Δf = 100 khz. In Fig. 6 (b), large secondary lobes are generated, while in Fig. 6 (a), the frequency difference leads to the smoothing effect in the focal region over time and the generation of a single main lobe. Numerically, an inverse relationship between the minimum frequency difference required, Δfmin, and pulse length was determined, as shown in Fig. 6 (c).

Fig. 6.

(a) Contour plots of experimental maximum pressure distribution for confocal transducers driven at 514 and 614 kHz in water, with F-number 1.2 and an angular separation of 90°. (b) Contour plot of experimental maximum pressure distribution for confocal transducers driven with 30 cycle sinusoidal pulses both at 514 kHz in water, with an angular separation of 90°. (c) Relationship between minimum frequency difference, Δfmin, and pulse length determined from simulation results.

B. Standing wave mitigation

Numerical simulations:

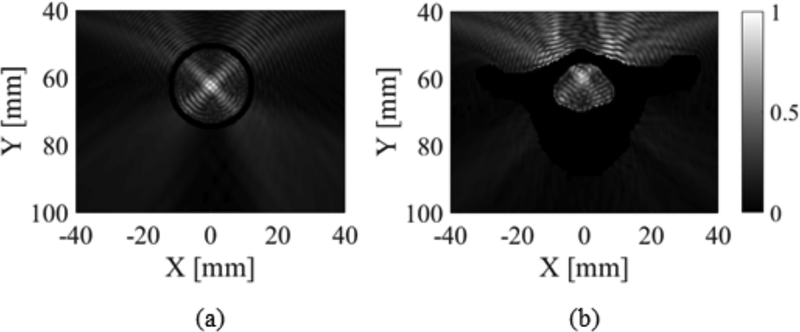

When simulating focusing within a reflecting cavity, such as the acrylic tube phantom or one of the thoracic vertebrae, a clear interference pattern corresponding to the formation of standing waves was observed. Fig. 7 shows the normalized maximum pressure distribution within the acrylic tube phantom and T1. In both cases, standing waves are present.

Fig. 7.

(a) Normalized maximum pressure distribution for a simulation of a confocal F-number 1.2 transducers driven at 514 and 614 kHz focusing within an acrylic tube phantom (θ = 90°). (b) Normalized maximum pressure distribution for a k-Wave simulation of a confocal F-number 1.2 transducers driven at 514 and 614 kHz focusing within T1 (θ = 90°). The pressures within the acrylic and the bone are excluded.

The normalized S-numbers for each modified pulsing regime compared to the control case in the acrylic tube phantom are shown in Table II.

TABLE II.

Normalized S-Numbers For Modified Pulsing Regimes For Simulations In Acrylic Tube Phantom

| Pulsing Regime | Normalized S-number |

|---|---|

| 200kHz Chirp | 0.44 |

| BPSK (n=l) | 0.40 |

| QPSK (n=l) | 0.38 |

| Short burst excitation | 0.36 |

| Short burst excitation with PSK | 0.22 |

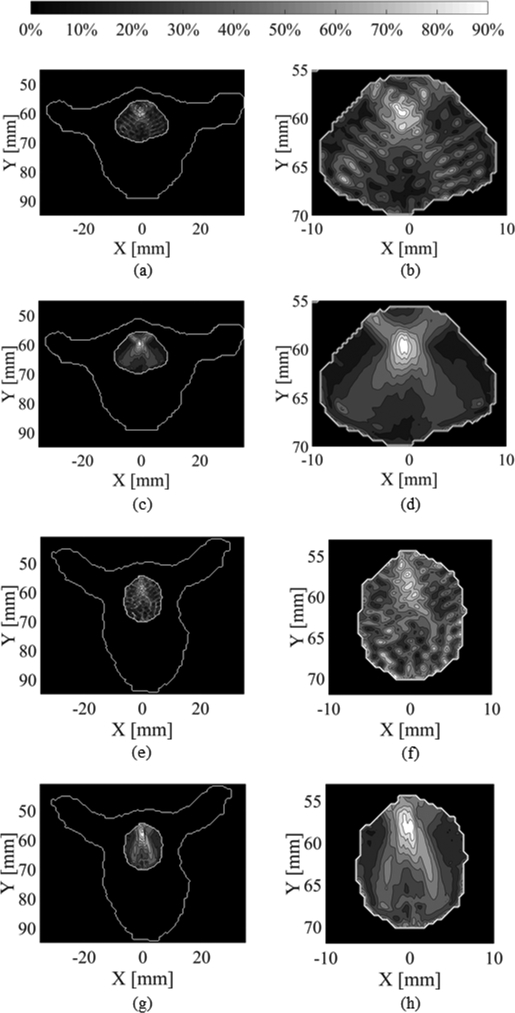

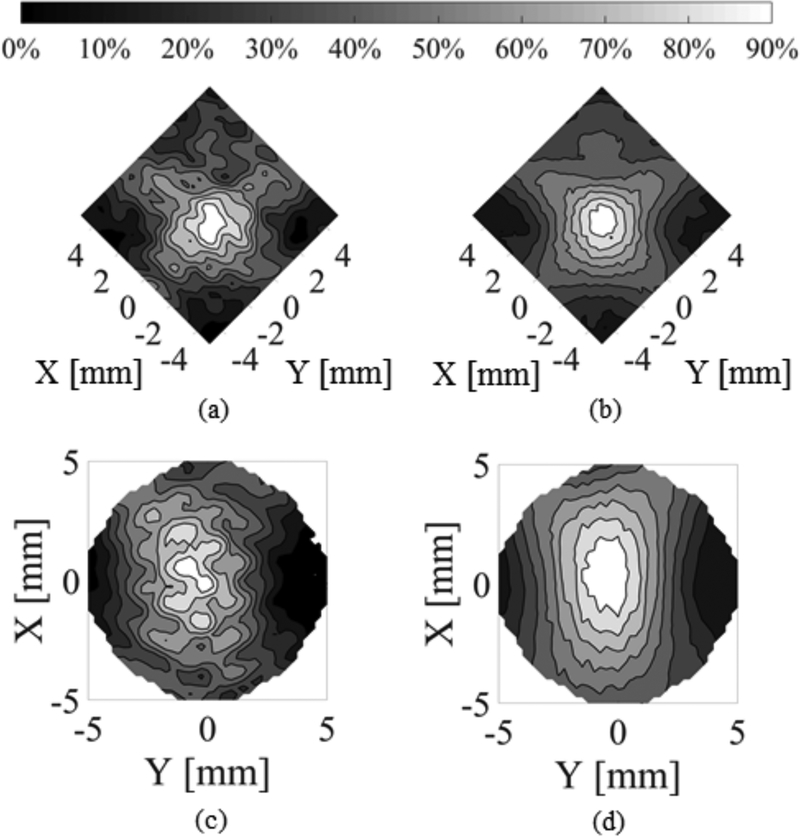

Simulations in the vertebrae also show promising results for the mitigation of standing waves. An example using the combination of short burst excitations with PSK is shown in Fig. 8. Fig. 8 (a)–(b) and (e)–(f) show the maximum pressure distribution using the control pulse (514, 614khz) in T1 and T5 respectively. Fig. 8 (c)–(d) and (g)–(h) show the maximum pressure distribution using short burst excitations with PSK (514, 614khz) in T1 and T5 respectively, and show more uniform focal spots compared to the control pulse.

Fig. 8.

Contour plots of the simulated maximum pressure distribution in the T1 vertebral canal for confocal, F-number =1.2 transducers at 514 and 614 kHz, with θ = 90° driven with (a)-(b) N = 30 pulses, and (c)-(d) N = 2 pulses combined with PSK. Contour plots of the simulated maximum pressure distribution in the T5 vertebral canal, for the same transducer parameters and θ = 60° for (e)-(f) N = 30 pulses, and (g)-(h) N = 2 pulses combined with PSK. (b), (d), (f) and (h) are magnified versions of (a), (c), (e) and (g) respectively.

Benchtop experiments – Single Transducer:

BPSK was not investigated experimentally due to its similar performance to QPSK in numerical simulations. Instead, a pulsing regime consisting of short burst excitations combined with time delays corresponding to PSK was tested. In total, five (5) pulsing regimes were investigated for mitigation of standing waves on the benchtop. These could be subdivided into two categories: (1) long-burst regimes and (2) short-burst regimes. The long-burst pulses were a 200khz chirp and a QPSK pulse (n=1), with pulse lengths equivalent to the control pulse. The short-burst pulses were a 2-cycle pulse train, a 2-cycle pulse train with PSK and a 2-cycle pulse train with time delays.

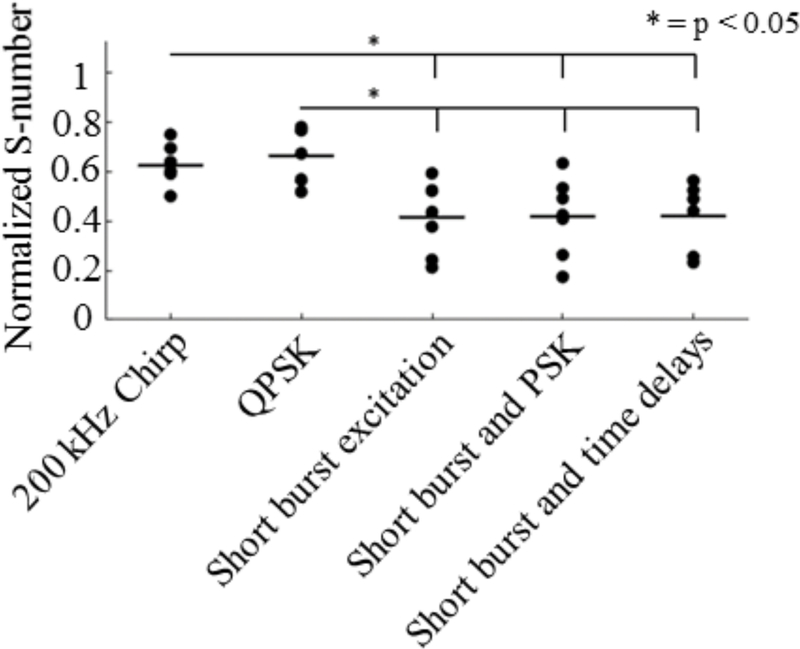

A plot of the normalized S-numbers compared with the control case across samples using a single transducer is shown in Fig. 9. While all methods did reduce standing wave content compared with the control case, short-burst methods performed significantly better than long-burst methods. A one-way ANOVA indicated significant difference among the groups (p = 0.0006). Through post-hoc Tukey testing, no significant difference was found either between long-burst methods or among short-burst methods. For example, the 200khz chirp vs. QPSK had p = 0.98, and short burst excitations vs. Short bursts with PSK had p = 1.00. Comparatively, QPSK vs. Short burst excitation had p = 0.01. These results imply that for the single transducer case the most important factor for mitigating standing waves in a cavity of this size is the pulse length.

Fig. 9.

Normalized S-numbers compared to a control case for different methods of standing wave mitigation with a single transducer driven at 514 kHz in the acrylic tube phantom and 6 ex vivo thoracic vertebrae. Bars represent the sample mean.

Benchtop experiments – Dual Aperture:

From single aperture investigations, it is apparent that short pulses are appropriate for reducing the effects of standing waves at 514khz in a reflecting cavity such as the human thoracic spinal canal. However, it is difficult to achieve the effects of confocal, dual-frequency FUS with short pulse durations (Fig. 6 (b)). The results show that the combination of short burst excitations with PSK leads to the generation of a single main lobe at the focus of the transducers and simultaneously negates the Δfmin requirement. Fig. 10 shows a comparison between short burst excitations and short burst excitations combined with PSK in water at 514 khz.

Fig. 10.

Contour plots of the experimental maximum pressure distribution in water for confocal F-number = 1.2 transducers driven at 514 kHz with θ = 90° using (a) short burst excitation and (b) short burst excitation and PSK.

Similar results were obtained both using a synthetic dual aperture (i.e. Measurements obtained for single transducer case and time domain data added in post processing in MATLAB.) In the acrylic tube phantom, T1 and T5 and using two physical transducers in the phantom and T1. Fig. 11 shows the comparison between the control pulse and the combination of short burst excitations with PSK in T1 and T5.

Fig. 11.

Contour plots of the experimental maximum pressure distribution in the T1 vertebral canal for F-number = 1.2 transducers driven at 514 kHz and 614 kHz using a synthetic dual aperture set up with θ = 90° using (a) N = 30 pulses, and (b) N = 2 pulses combined with PSK. Contour plots of the experimental maximum pressure distribution in the vertebral canal for the same transducer parameters using a synthetic dual aperture set up with θ = 60° using (a) N = 30 pulses, and (b) N = 2 pulses combined with PSK. In (a) and (b) transducers are parallel to the axes, while in (c) and (d) they form an angle with the axes. In (c) and (d), there are no experimental data for the corners of the plots.

IV. Discussion

The feasibility of creating a controlled focus within human thoracic vertebrae has been demonstrated ex vivo. A confocal, dual aperture approach led to a focal depth of field that was more appropriate, given the size of the vertebral canal, compared to a single aperture case (Fig. 4). This result is due to the temporal superposition of pressure fields from the two transducers. The introduction of a frequency difference between the transducers allows for the smoothing of the spatial pressure distribution over time [30]. For shorter pulse lengths, it is more difficult to achieve the smoothing effect, leading to increased values of Δf. In this study, all pulse lengths used were short compared to previous work [29], [30] which used pulse lengths on the order of 10ms. As a result, larger values of Δf were required for this study (Order of magnitude: 10–100khz compared to 10Hz). The dual aperture approach was superior to a single aperture approach as it produced a 70% contour small enough to fit within the human thoracic vertebral canal. The reduction in focal depth of field that has been demonstrated is important as it will allow for greater precision in FUS treatments in the vertebral canal compared to a single aperture case.

The combination of short burst (N = 2) excitations and PSK has been shown to be a promising method of standing wave reduction in the thoracic vertebral canal both numerically and experimentally. This pulse is advantageous as it eliminates both standing waves and the interference pattern at the focus when using short bursts in the dual aperture configuration (Fig. 11), and can be easily implemented in practice using either phase or time delays to generate phase shifts within the pulses. Short bursts (N = 2) are superior to the N = 30 control pulse because the short pulse lengths and broad frequency content of short pulses minimize interference between incident and reflected waves within the vertebral canal. However, such short bursts do not achieve a single main focal lobe in the dual aperture set up, as the Δf required for spatial smoothing becomes extremely large. To compensate for this, instead of a frequency difference, random PSK, applied individually to each transducer, can be used to achieve the same effect over multiple bursts. The improved focal control (Fig. 11) compared to the N = 30 control pulse is necessary for therapeutic applications since standing wave content is difficult to predict. A shift in vertebral position on the order of 1mm can greatly alter the pressure distribution and standing wave content within the vertebral canal.

The chirp pulse (~3ghz/s) and short pulses used experimentally were likely subject to bandwidth limitations of the transducers. Piezocomposite transducer elements were used to achieve the necessary bandwidth to accommodate chirps and short pulse lengths. However, the transducers used in this study were air-backed, and the addition of a backing layer could further improve the transducer bandwidth.

Although this study did not include in vivo investigations, short pulses have previously been successful for BBBO [21], [35], [42]. Future investigations into the response of mbs to short pulses with PSK, both on the bench and in vivo, will allow treatments to be optimized for this pulse scheme. The effects of other exposure parameters, including the PRP and pulse train length and repetition frequency of the pulse train should also be investigated in future work.

Limitations of this study include the simplified numerical simulations, the hydrophone orientation and difficultly performing measurements covering the extent of the vertebral canal. The k-Wave model used in the simulations makes several simplifications, including modeling only two dimensions, assuming bone homogeneity and not accounting for shear mode propagation of ultrasound though vertebral bones. This is unrealistic, especially considering the complicated geometry of vertebral bone and the dependence of longitudinal and shear mode transmission on incidence angle [43].

The assumption of bone homogeneity may be insufficient to capture the complexity of ultrasound propagation through vertebral bone, which has been shown to have varying density and complex trabecular structures [44]. Recently, image homogenization has been shown to contribute to the underestimation of transmitted amplitude and time-of-flight in transcranial simulations [45], and is likely to under-predict focal distortions. Additionally, the acoustic properties used in these simulations were based on skull bone, and these may not be transferrable to vertebral bone. Unlike the skull, the vertebrae are load bearing structures, with trabeculae aligned along lines of stress [46], and it has been shown that the directions of trabecular orientation influence acoustic properties [47]. However, it is important to note that the posterior elements of human vertebrae, including the lamina, have a much reduced ratio of trabecular bone to cortical bone when compared to anterior elements [48], so the simulations performed in this study may be less affected by the assumption of homogeneity. Considering these limitations, the simulation results in this paper should be viewed only as a guideline for experimental work, as was intended.

For benchtop experiments, the hydrophone was orientated perpendicular to the axis of the transducers (Fig. 2). This means that the hydrophone shaft obstructs some sound travelling from the transducer face to the focus, leading to some focal distortion. Although this effect is not evident in the axial scans presented in this paper, and therefore does not pose an issue for this study, it does lead to focal distortion in the transverse plane [49]. Due to the fragility of the hydrophone and limitations of the scan arm software, only square grids (~10mm × 10mm) were measured within the vertebral canal. This means that there was some data that could not be captured, especially near the walls of the canal.

The results of numerical simulations and benchtop experiments presented in this paper, were done at room temperature, rather than the human body temperature of 37°C. Although the temperature impacts the speed of sound in a medium, it should not impact the results of this paper showing depth of field reduction and standing wave mitigation. Additional simulations and experiments were conducted at 37°C to confirm the results shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 11. These results confirmed that a controlled focus can be achieved in the thoracic vertebrae using a dual aperture approach and short burst excitations in combination with PSK.

Having demonstrated the feasibility of using a dual aperture approach and short bursts with PSK for creating a controlled focus within ex vivo thoracic vertebrae, future work will include the investigation of MB response to the selected exposures both on the benchtop and in vivo. Additionally, the selected exposures will be investigated for their safety and efficacy for BSCBO in vivo in a clinically relevant, large animal model. Ultimately these methods will be implemented on a phased array to allow for aberration correction and focal steering, providing even greater control of the therapeutic focus.

V. Conclusion

The feasibility of using a dual aperture approach and short burst exposures combined with PSK to achieve a controlled focus has been demonstrated in ex vivo human thoracic vertebrae. These exposures were shown to successfully reduce the focal depth of field and suppress standing waves through numerical simulations and benchtop experiments. Future work will focus on investigating MB response to the selected exposures and implementation in vivo.

Acknowledgments

S-M. P. Fletcher would like to thank R. Xu for simulation and experimental assistance, B. Hynynen for experimental assistance, and T. Watson for general assistance. She would also like to thank P. Wu, S. Seerala, A. Chau, R. Reyes and L. Deng for their assistance with transducer fabrication.

This work was supported in part by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through the Discovery Grant program, and by the U.S. National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) under Grant R21 EB023996–01.

Contributor Information

Stecia-Marie P. Fletcher, Physical Sciences Platform, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada and the Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, ON, Canada (sfletcher@sri.utoronto.ca)

Meaghan A. O’Reilly, Physical Sciences Platform, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada and the Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, ON, Canada (moreilly@sri.utoronto.ca).

References

- [1].Bartanusz V, Jezova D, Alajajian B, and Digicaylioglu M, “The blood-spinal cord barrier: Morphology and clinical implications,” Ann. Neurol, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 194–206, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pardridge WM, “Blood-brain barrier delivery,” Drug Discov. Today, vol. 12, no. 1–2, pp. 54–61, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pardridge WM, “The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development,” Neuro Rx J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neurother, vol. 2, pp. 3–14, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Burgess A and Hynynen K, “Noninvasive and targeted drug delivery to the brain using focused ultrasound,” ACS Chem. Neurosci, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 519–526, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Burgess A and Hynynen K, “Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound,” Expert Opin. Drug Deliv, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 711–721, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rossi F, Perale G, Papa S, Forloni G, and Veglianese P, “Current options for drug delivery to the spinal cord.,” Expert Opin. Drug Deliv, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 385–396, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hynynen K, Mcdannold N, Vykhodtseva N, and A Jolesz F, “Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits.,” Radiology, vol. 220, no. 3, pp. 640–646, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Treat LH, Mcdannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Zhang Y, Tam K, and Hynynen K, “Targeted delivery of doxorubicin to the rat brain at therapeutic levels using MRI-guided focused ultrasound,” Int. J. Cancer, vol. 121, no. 4, pp. 901–907, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liu H-L et al. , “Blood-brain barrier disruption with focused ultrasound enhances delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs for glioblastoma treatment,” Radiology, vol. 255, no. 2, pp. 415–425, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aryal M, Vykhodtseva N, Zhang Y-Z, Park J, and Mcdannold N, “Multiple treatments with liposomal doxorubicin and ultrasound-induced disruption of blood-tumor and blood-brain barriers improves outcomes in a rat glioma model,” J. Control. Release, vol. 169, no. 0, pp. 103–111, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Burgess A, Ayala-Grosso CA, Ganguly M, Jordão JF, Aubert I, and Hynynen K, “Targeted delivery of neural stem cells to the brain using MRI-guided focused ultrasound to disrupt the blood-brain barrier,” plos One, vol. 6, no. 11, p. E27877, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alkins R, Burgess A, Kerbel R, Wels WS, and Hynynen K, “Early treatment of HER2-amplified brain tumors with targeted NK-92 cells and focused ultrasound improves survival,” Neuro. Oncol, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 974–981, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Poon C, Mcmahon D, and Hynynen K, “Neuropharmacology Noninvasive and targeted delivery of therapeutics to the brain using focused ultrasound,” Neuropharmacology, vol. 120, pp. 20–37, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Huang Y et al. , “Initial experience in a pilot study of blood-brain barrier opening for chemo-drug delivery to brain tumors by MR-guided focused ultrasound,” in Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wachsmuth J, Chopra R, and Hynynen K, “Feasibility of transient image-guided blood-spinal cord barrier disruption,” AIP Conf. Proc, vol. 1113, no. 1, pp. 256–259, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Weber-Adrian D et al. , “Gene delivery to the spinal cord using MRI-guided focused ultrasound.,” Gene Ther, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 568–577, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Payne AH et al. , “Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound to increase localized blood-spinal cord barrier permeability,” Neural Regen. Res, vol. 12, no. 12, pp. 2045–2049, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].O’Reilly MA et al. , “Preliminary investigation of focused ultrasound-facilitated drug delivery for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastases,” Sci. Rep, vol. 8, no. 9013, pp. 1–8, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pichardo S, Sin VW, and Hynynen K, “Multi-frequency characterization of the speed of sound and attenuation coefficient for longitudinal transmission of freshly excised human skulls,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 219–250, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Panjabi MM et al. , “Thoracic human vertebrae: Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy,” Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976)., vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 861–869, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Reilly MA, Waspe AC, Ganguly M, and Hynynen K, “Focused-ultrasound disruption of the blood-brain barrier using closely-timed short pulses: Influence of sonication parameters and injection rate,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 587–594, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kerr CL, Gregory DW, Shammari M, Watmough DJ, and Wheatley DN, “Differing effects of ultrasound-irradiation on suspension and monolayer cultured hela cells, investigated by scanning electron microscopy,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 397–401, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Eller A, “Force on a bubble in a standing acoustic wave,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 43, pp. 170–171, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Azuma T, Kawabata K, and Umemura S, “Schlieren observation of therapeutic field in water surrounded by cranium radiated from 500 khz ultrasonic sector transducer,” 2004 IEEE Ultrason. Symp, pp. 1001–1004, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Connor CW and Hynynen K, “Patterns of thermal deposition in the skull during transcranial focused ultrasound surgery,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 1693–1706, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Baron C, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Meairs S, and Fink M, “Simulation of intracranial acoustic fields in clinical trials of sonothrombolysis.,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 35, no. 7, pp. 1148–1158, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Daffertshofer M et al. , “Transcranial low-frequency ultrasound-mediated thrombolysis in brain ischemia: Increased risk of hemorrhage with combined ultrasound and tissue plasminogen activator - Results of a phase II clinical trial,” Stroke, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 1441–1446, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Song J, Pulkkinen A, Huang Y, and Hynynen K, “Investigation of standing wave formation in a human skull for a clinical prototype of a large-aperture, transcranial MR-guided Focused Ultrasound (mrgfus) phased array: An experimental and simulation study,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 435–444, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sutton J, Power Y, Zhang Y-Z, Vykhodtseva N, and Mcdannold N, “Design, characterization, and performance of a dual aperture, focused ultrasound system for microbubble-mediated, non-thermal ablation in rat brain,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 138, no. 3, pp. 1821–1821, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sun T, Sutton JT, Power C, Zhang Y, Miller EL, and Mcdannold NJ, “Transcranial cavitation-mediated ultrasound therapy at sub-mhz frequency via temporal interference modulation,” Appl. Phys. Lett, vol. 111, no. 163701, pp. 1–4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mitri FG, Greenleaf JF, and Fatemi M, “Chirp imaging vibro-acoustography for removing the ultrasound standing wave artifact,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 1249–1255, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Erpelding TN, Hollman KW, and O ‘Donnell M, “Bubble-based acoustic radiation force using chirp insonation to reduce standing wave effects,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 263–269, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tang SC and Clement GT, “Standing-wave suppression for transcranial ultrasound by random modulation,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 203–205, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tang SC and Clement GT, “Acoustic standing wave suppression using randomized phase-shift-keying excitations,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 126, no. 4, pp. 1667–1670, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].O’Reilly MA, Huang Y, and Hynynen K, “The impact of standing wave effects on transcranial focused ultrasound disruption of the blood-brain barrier in a rat model,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 55, no. 18, pp. 5251–5267, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Choi JJ and Coussios C-C, “Spatiotemporal evolution of cavitation dynamics exhibited by flowing microbubbles during ultrasound exposure,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 132, no. 5, pp. 3538–3549, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pouliopoulos AN, Li C, Tinguely M, Garbin V, Tang M-X, and Choi JJ, “Rapid short-pulse sequences enhance the spatiotemporal uniformity of acoustically driven microbubble activity during flow conditions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, vol. 140, no. 4, pp. 2469–2480, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Treeby BE and Cox BT, “k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields,” J. Biomed. Opt, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 21314–2- 21314–12, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tanaka M, Girard G, Davis R, Peuto A, and Bignell N, “Recommended table for the density of water between 0°C and 40°C based on recent experimental reports,” Metrologia, vol. 38, pp. 301–309, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Onda Corporation, “Acoustic properties of plastics,” 2003. [Online]. Available: http://www.ondacorp.com/images/Plastics.pdf. [Accessed: 09-Mar-2018].

- [41].Nhan T, Burgess A, Cho EE, Stefanovic B, Lilge L, and Hynynen K, “Drug delivery to the brain by focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier disruption: Quantitative evaluation of enhanced permeability of cerebral vasculature using two-photon microscopy,” J. Control. Release, vol. 172, no. 1, pp. 274–280, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Choi JJ, Selert K, Vlachos F, Wong A, and Konofagou EE, “Noninvasive and localized neuronal delivery using short ultrasonic pulses and microbubbles,” PNAS, vol. 108, no. 40, pp. 16539–16544, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].White PJ, Clement GT, and Hynynen K, “Longitudinal and shear mode ultrasound in human skull bone,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 1085–1096, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Banse X, Devogelaer JP, Munting E, Delloye C, Cornu O, and Grynpas M, “Inhomogeneity of Human Vertebral Cancellous Bone: Systematic Density and Structure Patterns Inside the Vertebral Body,” Bone, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 563–571, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Robertson J, Urban J, Stitzel J, and Treeby BE, “The effects of image homogenisation on simulated transcranial ultrasound propagation,” Phys. Med. Biol, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pal GP, Cosio L, and V Routal R, “Trajectory Architecture of the Trabecular Bone Between the Body and the Neural Arch in Human - Vertebrae,” Anat. Rec, vol. 222, pp. 418–425, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].F Nicholsont PH, Haddaway MJ, and J Daviet Charles MW, “The dependence of ultrasonic properties on orientation in human vertebral bone,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 39, pp. 1013–1024, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nottestad SY, Baumel JJ, Kimmel DB, Recker RR, and Heaney RP, “The proportion of trabecular bone in human vertebrae,” J. Bone Miner. Res, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 221–229, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Xu R and O’Reilly MA, “Simulating transvertebral ultrasound propagation with a multi-layered ray acoustics model,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 63, no. 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]