Abstract

Objective.

To assess whether recent anti-immigration rhetoric is significantly associated with inadequate prenatal care.

Methods.

This was a population-based cohort study (2011–2017). In their native language, patients were consented and queried regarding country of origin and time in the United States. Additional variables were collected or abstracted from the medical record, including documentation and timing of prenatal visits. Based on relevance and prevalence during the study period, publicly available Google search trends were mined for the terms “Make America Great Again,” “Mexico Wall,” and “Deportation” by geographic region. The time of first deviation from the mode Google search popularity value for each term was ascertained (mode inflection date). Perinatal data was averaged over 15 day moving windows, and the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index (APNCU) was used to categorically define inadequate prenatal care by validated standards.

Results.

Twenty-four thousand nine hundred thirty-three deliveries occurred during the study period. A mode inflection date was extrapolated from Google trend analytics and used to define the period prior to change in trends use pre (before rhetoric) and post (after rhetoric). Coincident to the rhetoric change, there was a significant increase in days until first prenatal visit, fewer prenatal visits and a decreased trend of mean hemoglobin nadir among U.S. non-native Hispanics (p<0.001). Immigrant status was an independent predictor of inadequate prenatal care as defined by the APNCU standard with increased adjusted odds among Hispanics (aOR 1.581, 95% CI 1.407–1.7771.4–1.8) coincident with anti-immigration rhetoric.

Conclusion.

Our findings are of likely significant public health importance, and suggest that recent anti-immigrant rhetoric is associated with adequate, timely, and regular access to prenatal care among nearly 25,000 deliveries in Houston, Texas.

Precis:

There is a temporal association between increased anti-immigrant political rhetoric and inadequate prenatal care among U.S. native and U.S. non-native gravidae.

Introduction

Addressing social determinants of health has become a critical concern in all areas of medicine. Significant ethnic and racial inequities with respect to both access to care and health outcomes are evident across multiple specialties, including obstetrics.1–3 Barriers to healthcare access may result from real or perceived social exclusion, which lead to delayed or fewer preventive health services, resulting in relatively worse outcomes when compared to similar individuals with legal resident status4–7.

Routine and early prenatal care is accepted as offering protection against maternal and infant morbidity and mortality and is a well-accepted standard of care8–9 Alongside attending regular prenatal care visits, identifying and treating common conditions of pregnancy (such as iron deficiency anemia) serve as reasonable proxies of access to standard obstetrical care.10–11

Current debate over immigration policies, deportation activities, and its accompanying political rhetoric may contribute to a sense of isolation among Hispanic, Latino, and undocumented patients. Immigrant responses to these exclusionary policies has been to adopt a policy of community avoidance.12,13However, research associating access and utilization of health care, particularly adequacy of prenatal care, to recent immigration policies, and the anti-immigrant rhetoric which accompanies such policies, is limited and has not yet extended to measures of adequacy of prenatal care.14,15

The aim of this study was not to argue for or against any policy nor practice of immigration reform, but rather to identify whether an association exists between anti-immigrant rhetoric and receipt of adequate prenatal care among patients who deliver in a U.S. based hospital.

Methods

This research study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (H-26364, most recent approval March 2, 2018; H-43085, most recent approval June 5, 2018). This is a retrospective population-based cohort study (August 2011 through July 2017) designed to evaluate rates and timing of prenatal care among women before and after significant increases in anti-immigrant political rhetoric. Hispanic and Latino women (hereafter condensed to “Hispanic”) were the cohort of interest, and were stratified by birth country of origin. These patients were compared against all other gravidae in the cohort, consistent with a population-based design. All patients in the cohort delivered at one of our two obstetrical hospitals (Ben Taub Hospital and the Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women, Houston, TX), and all patients delivering at either of these two hospitals were approached and consented and enrolled at the time of delivery for inclusion in our institutional database, PeriBank. 16. All patients in PeriBank are directly queried following consent regarding their birth country, parental birth country, duration in the U.S., and 5-digit zip code of residence and work through each trimester. Additional direct query and abstracted data included the patient history (including prior occurrence of preeclampsia and diabetes, smoking status, nicotine and substance use, familial obstetrical history, and entry into care, number of prenatal visits, and location of prenatal care clinics and providers), socioeconomic status (education, income, immigration status, birth country, time in the U.S.) and residential and workplace data (each trimester of pregnancy residence and work place five-digit zip code). Additional abstracted data analyzed in this study included the nadir hemoglobin value, as well as multiple comorbidities which may increase or decrease number of prenatnal visits (e.g., gestational diabetes, substance abuse). Given that treatment of iron deficiency anemia is standard obstetrical care, mean nadir hemoglobin measures were intended to be reasonable secondary objective proxy measures of attainment of prenatal care.

Patients included in the current study were enrolled in our PeriBank database between August 2011 through July 2017 (N=24,933 deliveries). The index pregnancy is defined as the most recent pregnancy in the database for each patient. All women who delivered were identified, and all patients had detailed prenatal care by gestational age and number of visits verified and abstracted. Women were assigned to the before and after groups based on the date of delivery for the index pregnancy. PeriBank includes all births occurring at both hospitals (Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women and Ben Taub Hospital). These two hospitals are distinct from one another with respect to payer mix, race and ethnicity, insurance status, and other sociodemographic variables. When considered together, they are representative of the general population of births in Houston, Texas.

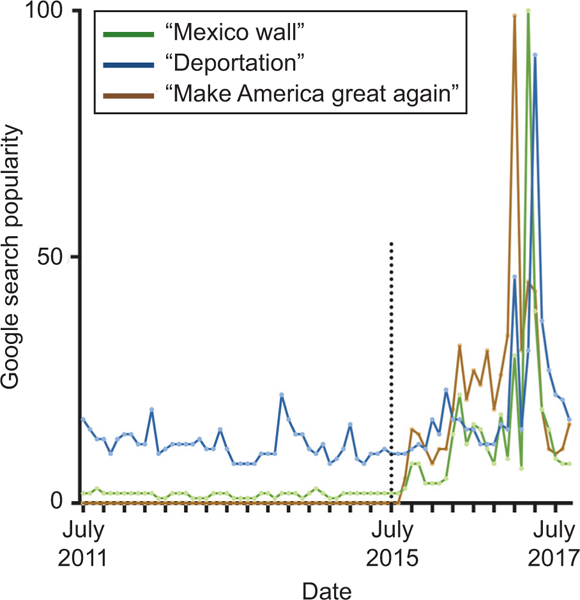

Publicly available Google search trends were mined for the search terms “Make America Great Again”, “Mexico wall” and “Deportation” by region, including the Southern United States (as defined by trends.google.com/explore/subregion, including Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, the Carolinas, Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee). These terms were chosen for their relation to common themes of the debate and accompanying political rhetoric surrounding immigration in the United States over our study time period and similarity of geographic region. Our choice of terms was further based on their representation of explicit (deportation, Mexico wall) and implicit (Make America Great Again) anti-immigrant sentiment. Since our population-based study aimed to determine the significance of association as aa large permeation and not just by increased usage of the terms, Google trend by a priori defined subregion and limited terms enabled best estimations true to the focus of the study in a contemporaneous region and time period. The time of first deviation from the mode Google search popularity value for each term was ascertained (mode inflection date). A mode inflection date of 7/1/2015 was extrapolated from the Google trend analytics and used to define the period prior to large scale change in trends in rhetoric use pre (before rhetoric) and post (after rhetoric) (Figure 1). No patient-specific data was used in determining these search terms, thus the terms and their inflection date were naïve to the primary outcome.

Figure 1.

Google search term analytics for anti-immigration rhetoric. The Google search popularity for the indicated search terms are provided for the years spanning the cohort’s enrollment period. July 2015 was chosen as it represented the major inflection point when the search terms experienced a spike in popularity.

The primary outcome in this analysis was adequacy of prenatal care. This was defined by multiple measures and means, including the gestational age at first prenatal visit, mean number of prenatal visits, and incidence of inadequate prenatal care in the index pregnancy. In order to categorically assign patients as having inadequate versus adequate or intermediate prenatal care, the previously validated and “gold standard” Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index (APNCU) was used.17,18,29 Briefly, the APNCU has been shown to be superior over the Kessner Institute of Medicine Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index when compared to its capacity for incorporating the month that prenatal care began, the proportion of the number of visits as recommended by the American College of Obstetrician Gynecologists (ACOG), and the gestational age at delivery. Inadequate prenatal care is thus defined as prenatal care begun after the 4th month or less than 50% of recommended prenatal visits received, as stratified by gestational age at delivery. Adequate and intermediate were collapsed into a single category, and defined as prenatal care begun by the 4th month and 50 to >100% of recommended visits received. All patients were categorized into either “inadequate” or “adequate/intermediate” for subsequent analysis.

All clinical and demographic data for pregnancies enrolled into our study were obtained from PeriBank as previously described.16 Preterm delivery was defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation. Groups of interest were compared by chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normal continuous variables. Given the large sample number, the normality of each data category was visually determined using histograms and normal Q-Q plots. Linear regression was performed for the trend in the before and after rhetoric groups.

In an effort to control for potential confounders, multivariate modeling was undertaken. Generalized linear models (GLMM, Proc GENMOD in SAS version 9.4) were used for estimation of Odds Ratio (OR), adjusted OR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for binomial outcome variables (inadequate prenatal care in this pregnancy [primary outcome]). Generalized linear mixed models (Proc GLIMMIX in SAS version 9.4) was used for estimation of least square means (LSM) for non-normally distributed continuous outcome variables and comparison between study groups. Adjustments were made for maternal age, Hispanic ethnicity, method of payment, gestational age at first visit, type 2 diabetes, chronic hypertension, and gestational age at diagnosis of preeclampsia in last pregnancy. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Because the exposure (change in anti-immigrant rhetoric) was measured over time and in relation to the primary outcome (sufficiency of prenatal care), there was no intent to ascribe causality per se and an E-value (as an estimate of the level of unmeasured confounding) was not calculated19.

Results

Baseline characteristics for the included cohort are shown in Table 1 and further divided by time relative to the identified date of rhetoric increase for Hispanic patients only in Table 2 and Table 3. Of the 23,580 patients included, 12,646 (46.3%) were not born in the U.S., with a majority originating from countries in Central America or Mexico. Compared to U.S. non-native patients, U.S. native patients had a greater average BMI, higher rate of preterm birth, a higher rate of Cesarean deliveries, and more frequently used tobacco, alcohol and other illegal or illicit substances. Patients born in Mexico, Central America and South America were generally more common in their exposures and outcomes, though individuals from South America were older, of a lower parity and had a greater rate of Cesarean deliveries than their other non-U.S. born Hispanic counterparts. For Hispanic patients, baseline characteristics of the enrolled cohort before and after rhetoric change remained the same, except for maternal age, maternal education, substance abuse and gestational diabetes (all of which were less common p<0.05). Overall, U.S. non-native patients had a lower BMI, and lower rates of preterm birth, Cesarean delivery, and polysubstance abuse.

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics by Birth Place and Ethnicity

| U.S. native Non-Hispanic (n=6592) | U.S. native Hispanic (n=3326) | U.S. non-native Hispanic (n=12569) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Characteristics | |||

| Country of Origin | |||

| US | 6592 | 3326 | 0 |

| Mexico | 0 | 0 | 7190 |

| Central America | 0 | 0 | 5078 |

| South America | 0 | 0 | 301 |

| Maternal Age (yr) | 29.8 = 5.6 | 25.9 = 6.1 | 29.3= 6.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.2 = 9.6 | 31.9 = 10.1 | 29.9 = 10.1 |

| Gestational Age at Delivery (weeks & days) | 269.9 = 18.4 | 269.3 = 19.1 | 270.5 = 16.8 |

| Preterm | 1048 (15.9%) | 469 (14.1%) | 1506 (13.6%) |

| Cesarean | 2795 (42.3%) | 1066 (32.1%) | 3149 (25%) |

| Gravidity* | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| Parity* | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–3) |

| Co-Morbidities | |||

| Gestational Diabetes | 392 (5.9%) | 230 (6.9%) | 1691 (13.4%) |

| Preeclampsia | 95 (1.4%) | 30 (0.9%) | 16 (0.1%) |

| Alcohol Use | 170 (2.6%) | 19 (0.6%) | 44 (0.3%) |

| Smoking | 1535 (23.3%) | 509 (15.3%) | 290 (2.3%) |

| Substance Use Disorder | 964 (14.6%) | 262 (7.9%) | 85 (0.7%) |

| *Range (IQR) | |||

Table 2.

Maternal Characteristics by Country of Origin

| U.S. n=11318 |

Mexico n=7376 |

Central America n=5277 |

South America n=330 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3329 | 7190 | 5078 | 301 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 7605 | 27 | 22 | 28 |

| Maternal Age (yr) | 28.6 ± 6.0 | 29.4 ± 6.4 | 28.9 ± 6.2 | 32.7 ± 5.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.7 ± 9.8 | 30.1 ± 10.1 | 29.6 ± 10.2 | 29.1 ± 7.6 |

| Gestational Age at Delivery (weeks & days) | 38&4 ± 2.4 | 38&5 ± 2.3 | 38&5 ± 2.2 | 38&5 ± 2.0 |

| Preterm | 1517 (13.4%) | 848 (11.8%) | 632 (12.0%) | 42 (12.7%) |

| Cesarean | 3861 (34.1%) | 1833 (24.9%) | 1203 (22.8%) | 138 (41.8%) |

| Gravidity* | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) |

| Parity* | 1 (0–1) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 0 (0–1) |

| Co-Morbidities | ||||

| Gestational Diabetes | 622 (5.5%) | 1055 (9.3%) | 626 (5.5%) | 23 (0.2%) |

| Preeclampsia | 125 (1.1%) | 13 (0.1%) | 3 (0.03%) | 2 (0.02%) |

| Alcohol Use | 189 (1.7%) | 24 (0.2%) | 14 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| Smoking | 2240 (19.8%) | 196 (1.7%) | 71 (0.6%) | 46 (0.4%) |

| Substance Use Disorder | 1226 (10.8%) | 49 (0.4%) | 26 (0.2%) | 11 (0.1%) |

| *Range (IQR) | ||||

Table 3.

Maternal Characteristics - Hispanic Patients Only

| Before Rhetoric Increase | After Rhetoric Increase | Before v. After (p) | U.S. Native vs. Non-native (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | U.S. Native (n=1324) | U.S. non-native (n=8115) | U.S. Native (n=2002) | U.S. non-native (n=4442) | ||

|

Maternal Characteristics |

||||||

| Maternal Age (yr) | 25.1±6.2 | 29.2±6.3 | 26.4±6 | 29.5±6.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.9±10.3 | 29.9±10.2 | 31.8±10.1 | 30±9.8 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Gestational Age at Delivery (weeks & days) | 38&3 ± 2.6 | 38&5 ± 2.2 | 38&5 ± 2.4 | 38&5 ± 2.4 | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Preterm | 214 (16.2%) | 961 (11.8%) | 252 (12.6%) | 536 (12.1%) | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Cesarean | 421 (31.8%) | 2060 (25.4%) | 642 (32.1%) | 1086 (24.4%) | 0.2 | 0.29 |

| Gravidity | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) | <0.001* | <0.001* |

| Parity | 1 (0–1) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001* | <0.001* |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 639 (50%) | 3090 (40%) | 711 (36%) | 1678 (39%) | 0.45 | 0.63 |

| Married | 599 (47%) | 4473 (57%) | 1236 (62%) | 2587 (59%) | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 36 (3%) | 254 (3%) | 40 (2%) | 90 (2%) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| More than High School | 360 (32%) | 397 (6%) | 1045 (53%) | 671 (16%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| High School or Less | 754 (68%) | 6229 (94%) | 926 (47%) | 3518 (84%) | ||

| Co-Morbidities | ||||||

| Gestational Diabetes | 117 (9%) | 1299 (16%) | 112 (6%) | 390 (9%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Preeclampsia | 6 (0.45%) | 5 (0.06%) | 24 (1.2%) | 11 (0.25%) | 0.5 | 0.72 |

| Alcohol Use | 10 (0.8%) | 19 (0.2%) | 9 (0.4%) | 24 (0.5%) | 0.006 | 0.65 |

| Smoking | 124 (9.4%) | 150 (1.9%) | 413 (20.6%) | 156 (3.5%) | 0.007 | 0.32 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 60 (4.5%) | 37 (0.5%) | 202 (10.1%) | 48 (1.1%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| *Range (IQR) | ||||||

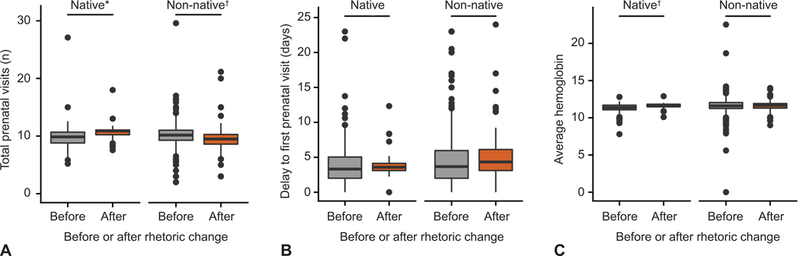

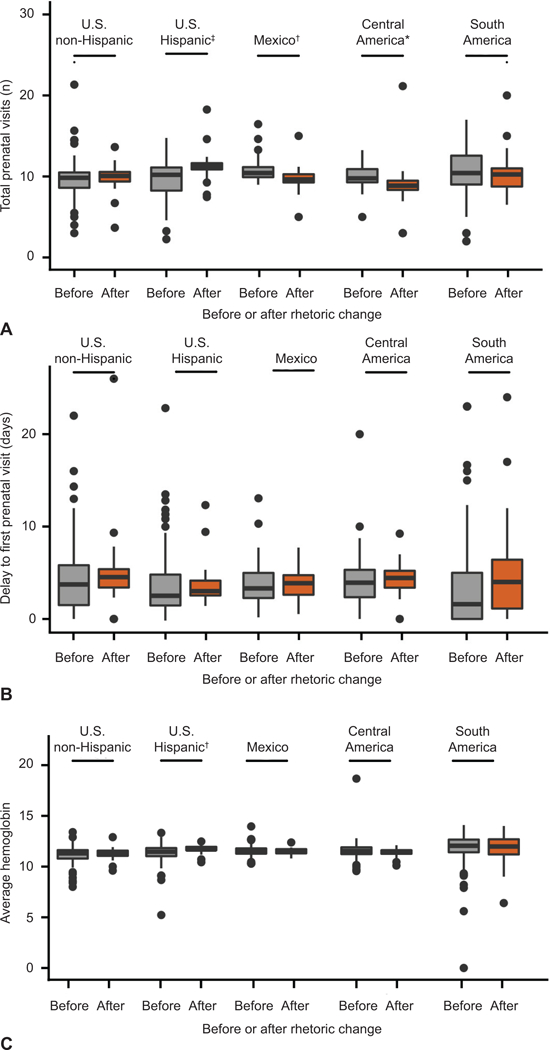

There was a significant reduction of total prenatal visits for U.S. non-native patients after the increase in anti-immigration rhetoric; in the same interval time period, there was a significant increase in the total number of prenatal visits for U.S. native patients (Figure 2A, p<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the delay to first prenatal visit for either group (Figure 2B). The nadir hemoglobin was increased for U.S. native patients over the study interval, but this was not true for U.S. non-natives(Figure 2C,p<0.05; Table 4. Comparisons by region of birthplace origin indicates the reduction of total of prenatal visits after rhetoric change was significant for patients from Mexico and Central America, but not South America (Figure 3A). Conversely, for U.S. native Hispanic gravidae, there was instead an increase in the total of prenatal visits (Figure 3A). However, there was no difference by region of birthplace in the delay before the first prenatal visit (Figure 3B), nor the nadir hemoglobin (Figure 3C), though U.S. native Hispanics saw a slight increase in the after rhetoric change period (Figure 3C).

Figure 2.

Comparisons of prenatal care between all U.S. native and U.S. non-native patients before and after rhetoric increase. Total number of prenatal visits (A), delay to first prenatal visit (B), and average hemoglobin (C). *P<.05; †P<.01.

Table 4.

Nadir Hemoglobin

| Before | After | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic U.S. native (n=2593) | 11.14 ± 0.91 | 11.28 ± 0.56 | n.s. |

| Hispanic U.S. non-native (n=6112) | 11.31 ± 0.93 | 11.66 ± 0.38 | <0.01 |

| Mexico (n=7376) | 11.53 ± 0.51 | 11.49 ± 0.33 | n.s. |

| Central America (n=5277) | 11.55 ± 0.90 | 11.38 ± 0.42 | n.s. |

| South America (n=330) | 11.67 ± 2.04 | 11.93 ± 1.19 | n.s. |

n.s.: non-significant

Figure 3.

Comparisons in prenatal care by country of birth. Data for total number of prenatal visits (A), delay to first prenatal visit (B), and average hemoglobin (C) stratified by country of origin, grouped into three major regions in the Americas. U.S. native patients shown as reference, stratified by non-Hispanic or Hispanic ethnicity. *P<.05; †P<.01, ‡P<.001.

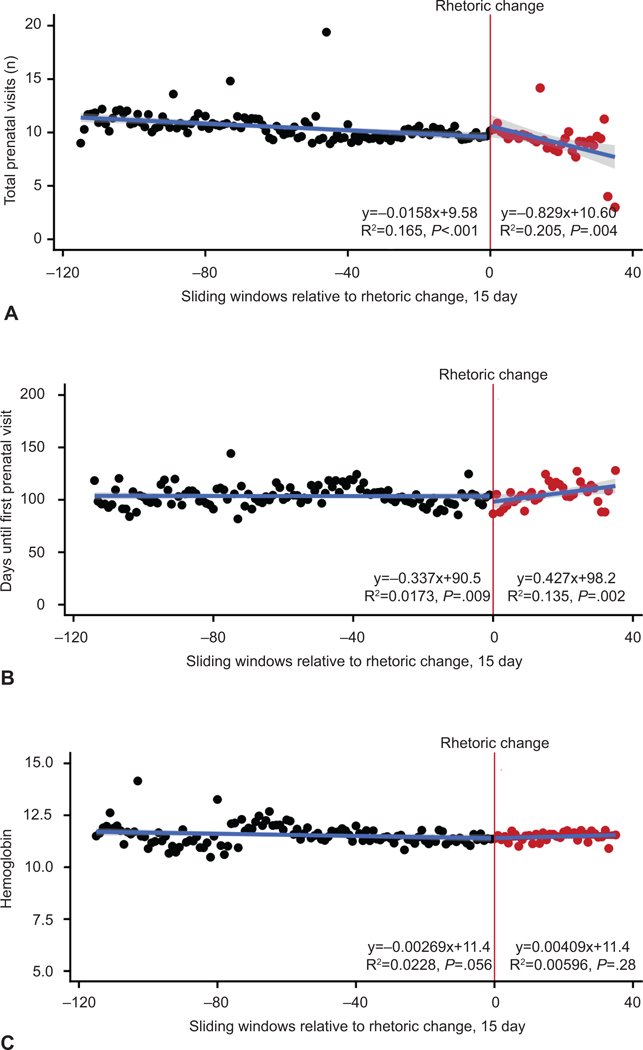

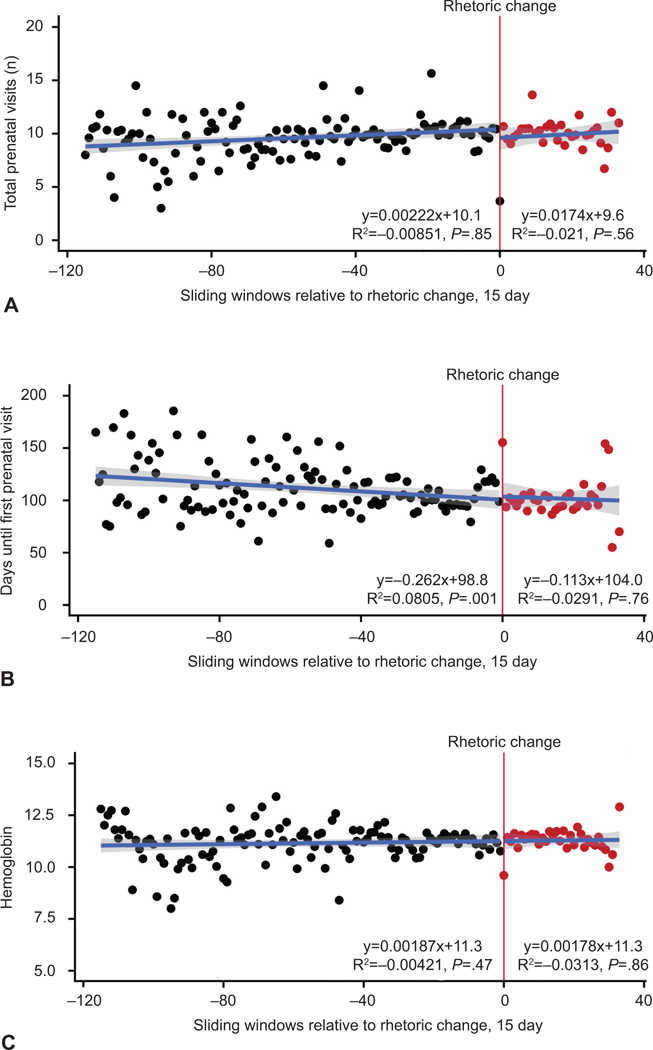

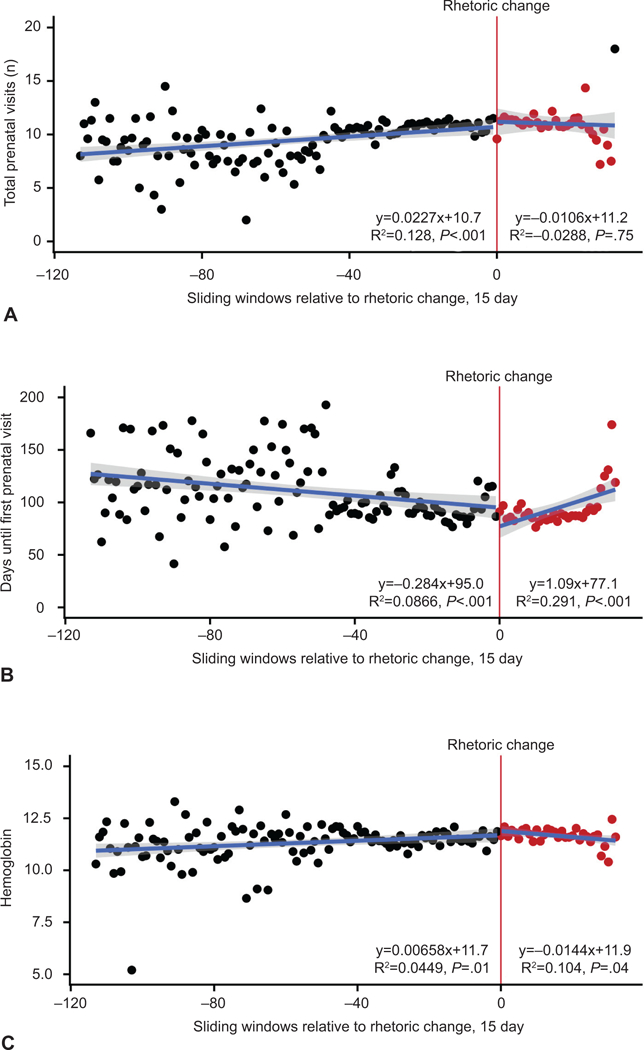

To evaluate for trending changes to prenatal care over time, patient data was averaged over 15 day sliding windows relative to the rhetoric date inflection point and a linear regression was fitted. There was a significant trending reduction of prenatal visits and an increase in days until first prenatal visits for Hispanic U.S. non-native, but not their U.S. native counterparts over time (Figure 4, Figure 5). There was similarly a significant trend for a greater delay until first prenatal visit for non-Hispanic U.S. native patients, although there was no significant trend in the total number of visits which remained the same before and after rhetoric change. (Figure 6). For all patients, the nadir hemoglobin remained constant during the time periods considered (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Trends in prenatal care relative to the increase in anti-immigration rhetoric, Hispanic U.S. non-natives. Data shown for total number of prenatal visits (A), delay until first prenatal visit (B), and antepartum hemoglobin measurements (C). Each dot represents an average value across 15-day intervals relative to the time of rhetoric increase (July 1, 2015). Black dots indicate before rhetoric change, red dots indicate after rhetoric change. Regression lines before and after this date are provided with the equation and significance shown.

Figure 5.

Trends in prenatal care relative to the increase in anti-immigration rhetoric, Hispanic U.S. natives. Data shown for total number of prenatal visits (A), delay until first prenatal visit (B), and antepartum hemoglobin measurements (C). Each dot represents an average value across 15-day intervals relative to the time of rhetoric increase (July 1, 2015). Black dots indicate before rhetoric change, red dots indicate after rhetoric change. Regression lines before and after this date are provided with the equation and significance shown.

Figure 6.

Trends in prenatal care relative to the increase in anti-immigration rhetoric, Non-Hispanic U.S. natives. Data shown for total number of prenatal visits (A), delay until first prenatal visit (B), and antepartum hemoglobin measurements (C). Each dot represents an average value across 15-day intervals relative to the time of rhetoric increase (July 1, 2015). Black dots indicate before rhetoric change, red dots indicate after rhetoric change. Regression lines before and after this date are provided with the equation and significance shown.

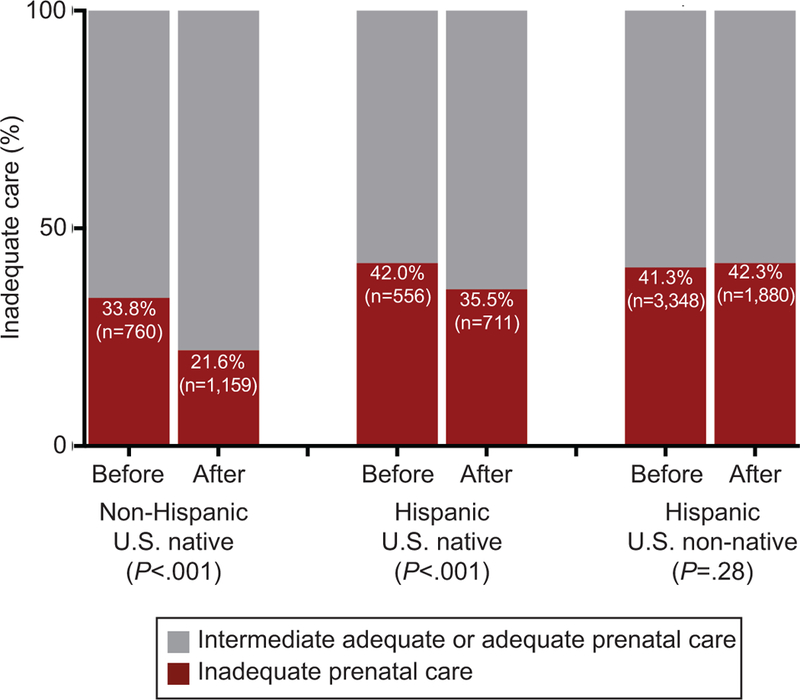

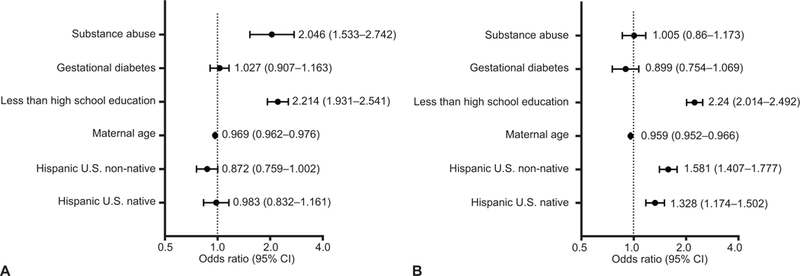

Adequate prenatal care was assessed using the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index (APNCU), which accounts for gestational age at delivery, the gestational age at the first prenatal visit, and the total number of visits.28,29 After rhetoric change, significantly fewer non-Hispanic U.S. native and Hispanic U.S. native patients had inadequate prenatal care (Figure 7, 33.8% to 21.6%; 41.9% to 35.5%; p<0.001). However, there was no significant change in the rate of inadequate prenatal care for Hispanic U.S. non-native patients (Figure 7, 41.3% to 42.3%, p=0.28). Thus, while all other patients observed a drop in the rate of inadequate and insufficient prenatal care, this same advantage was not seen among Hispanic U.S. non-native patients. A logistic regression model was fitted to formally evaluate the association between immigrant status and inadequate prenatal care, after controlling for maternal age, education, gestational diabetes and substance use (Table 5 Figure 8). In the time period before the rhetoric increase, less than a high school education (odds ratio, 2.214; CI 1.931–2.541) and substance use (odds ratio, 2.046; CI 1.533–2.742), but neither ethnicity nor immigrant status, were significantly associated with inadequate prenatal care. However, in the period after rhetoric change, both Hispanic U.S. native patients (odds ratio, 1.328; CI 1.174–1.502) and Hispanic U.S. non-native patients (odds ratio, 1.581; CI 1.407–1.777) were significantly more likely to have inadequate prenatal care (Table 5, Figure 8). Lastly, the adjusted odds ratios for Hispanic U.S. native and Hispanic U.S. non-native patients were statistically significant from each other (p=0.006), indicating that Hispanic immigrant status withstood as a significant predictor of inadequate prenatal care in the interval after rhetoric change.

Figure 7.

Rate of inadequate prenatal care among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic U.S. natives and non-natives. Inadequate care was determined by the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index and the proportion of individuals with inadequate care shown. Statistical significance determined by a two-sample proportion z-test.

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for Inadequate Prenatal Care

| Before Rhetoric Increase | After Rhetoric Increase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio#

(95% CI) |

Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio#

(95% CI) |

|

| Hispanic U.S. Native | 1.416 (1.231–1.628) | 0.983 (0.832–1.161) | 1.994 (1.782–2.231) | 1.328 (1.174–1.502)* |

| Hispanic U.S. non-native | 1.373 (1.245–1.515) | 0.872 (0.759–1.002) | 2.657 (2.433–2.903) | 1.581 (1.407–1.777)* |

| Maternal Age | 0.965 (0.959–0.97) | 0.969 (0.962–0.976)* | 0.974 (0.969–0.979) | 0.959 (0.952–0.966) * |

| Less than High School Education | 2.128 (1.908–2.376) | 2.214 (1.931–2.541) * | 1.576 (1.437–1.729) | 2.24 (2.014–2.492)* |

| Gestational Diabetes | 0.952 (0.854–1.062) | 1.027 (0.907–1.163) | 0.911 (0.826–1.004) | 0.899 (0.754–1.069) |

| Substance Use Disorder | 2.028 (1.57–2.628) | 2.046 (1.533–2.742)* | 1.051 (0.846–1.303) | 1.005 (0.86–1.173) |

Factors accounted for in model include Ethnicity, Maternal Age, Maternal Education, Gestational Diabetes, Substance Use Disordere

p<0.001

Figure 8.

Predictors of inadequate prenatal care. A generalized linear model was performed to assess the impact of being a Hispanic U.S. non-native before (A) and after (B) rhetoric change after adjusting for potential confounding factors. Forest plot shows adjusted odds ratios for inadequate prenatal care controlling for ethnicity, maternal age, maternal education, gestational diabetes, and substance abuse.

Discussion

Some recent studies support public funding of prenatal care for undocumented immigrants20–22. However, there are arguments to withhold care to this population, and some of these arguments stem from reform of immigration policies and anti-immigrant biases, not from informed public health interests per se23. Currently, many immigrants access prenatal care through services such as the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and locally-funded state programs, and service is provided regardless of documentation status. In particular, the safety net of care provided by CHIP is responsible for coverage of 36,000 pregnant women in Texas alone24. The Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018, passed into law December 21, 2017, provides $2.85 billion in funding allotments for CHIP for the first half of 201825.

Our data demonstrates, coincident with increasing anti-immigration statements as determined by increasing popularity of web-searches of “Make America Great Again”, “Mexico wall”, and “Deportation”, that there has been significant decreases in the numbers of routine prenatal care visits and a delay in prenatal care establishment for pregnant women of Central American and Mexican origin. This trend is not observed for women of South American origin, who represent a much smaller percentage of the currently recognized 11 million undocumented population in the United States26. However, given the much smaller number of South American women in our cohort, we likely lack the adequate power necessary to make comparisons to or generalizations about this demographic. It is important to note that over this study interval, and temporally coincident with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), we observed a decrease in the prevalence and incidence of insufficient and inadequate prenatal care among all cohorts except Hispanic U.S. non-native patients. Whether it is fear or social isolation driving these women away from seeking timely and sufficient prenatal care, numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between lack of prenatal care and an increased risk for poor prenatal outcomes such as low birth weight and preterm delivery27–29.

A trend to a decrease in the hemoglobin nadir after the increased shift in rhetoric was also noted within the Hispanic U.S. non-native population. This suggests that this population is likely not obtaining appropriate routine iron supplementation recommended for patients with hemoglobin <11 g/dL during pregnancy. Regardless of the availability and accessibility of services, our research adds to a growing body of evidence showing that recent political anti-immigration sentiments are being heard by our patients, and that immigrant populations are either avoiding, not seeking, and ultimately not receiving recommended care during pregnancy.

Our study’s primary limitation is the relative fewer number of cases since the rhetoric inflection point. Thus, detection for morbidity and mortality is likely relatively underestimated and underpowered, therefore limiting our conclusions. Our study is additionally limited by its inability to determine causation and inability to capture patients who go on to deliver in other hospitals or have no prenatal care. There may be unmeasured and unaccounted for confounding which we have not considered, and we thus make no statements regarding causality and rather present our findings as temporal associations. Influence of prior prenatal care experience and outcomes that may have in subsequent pregnancy fall outside the scope of this paper and would be of interest for investigation. Here, prior prenatal experience and access to care must be acknowledged as a potential occult confounder.

Our study is strengthened by application of a rigorous tool for determination of adequate versus inadequate prenatal care, the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index (APNCU). This accounts for initiation of care and gestational age at delivery, and thus appropriately measures prenatal visits relative to the total number of weeks in which it could be maximally received. Our study has additional strengths, including use of 15 day sliding windows relative to the rhetoric date inflection point, and fit of both linear regression and application of logistic regression. This enabled us to optimally detect temporal associations with rigorous multivariate statistical measures. Finally, we benefit from direct questioning of patients under consent. Our consent rate approximates 96%, and we utilize research coordinators native and fluent in Spanish.

In sum, in this study we demonstrate the temporal co-occurrence of measurable health inequities in association with political rhetoric. To improve and broaden access during pregnancy, thereby limiting potential social disparities, we would concur with recent suggestions aimed at universally adopting and promoting a climate of engagement and promotion of health care regardless of nationality and documentation status. Given the close association with political rhetoric, platforms for positive promotional activities could include social media, written materials, and public health address in multiple community, regional, and national forums aimed at the populations most affected.

This study makes no statements nor does it address the immigration debate per se, and it is not the goal nor intent of the investigators to proffer opinion nor statement of fact regarding immigration reform. Rather, it is our intent to bring to light the associated effects of such discussions and their accompanying political rhetoric on timing and receipt of prenatal care among a population that will stay in the U.S. to deliver their infant. Additionally, generalizability of our conclusions to Hispanic or Latino populations outside of Texas would require further investigation. With that said, it is evident that there is an imminent need for immigration reform yielding transparent and acceptable policies by the public at-large. Until such policies are constructed and implemented, there is an evident risk that political rhetoric will continue to bear a significant influence on health disparities in the U.S. In this report, we have documented the impact of such rhetoric as a significant decrease in the numbers of routine prenatal care visits and a delay in prenatal care establishment for pregnant women of Central American and Mexican origin. As had been documented for decades, insufficient access and receipt of prenatal care only increases the occurrence and severity of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality and propagates health disparities. In so much as obstetrician–gynecologists are acknowledged advocates of equitable care for women and their infants, it is incumbent on us to provide objectively acquired scientific data to better inform public discourse. It is our hope that ours and others data may be used by public health policy experts to design, enable, implement, and enact well-informed policies with a unified goal of not allowing rhetoric to dictate health outcomes, and to mitigate health disparities whenever possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Baylor College of Medicine Medical Scientist Training Program (Derrick M. Chu and Kjersti M. Aagaard, NIH HIGMS T32 GM007330), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Derrick M. Chu, T32GM088129), and the Baylor Research Advocates for Student Scientists (Derrick M. Chu).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented at the SMFM Pregnancy Meeting Dallas, Texas, February 3, 2018.

References

- 1.Bryant AS, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrical Outcomes and Care: Prevalence and Determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010. Vol 202(4):335–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDorman MF, Callaghan WM, et al. Trends in the Preterm-Related Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity, United States 1994–2004. International Journal of Health Services. 2007. Vol 37(4)635–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

- 4.Bustamente V et al. Variations in Healthcare Access and Utilization Among Mexican Immigrants: the Role of Documentation Status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012. 14(1):146–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ku L, Matani S. Left out: immigrants access to health care and insurance. Health Aff (Milwood) 2001;20(1):247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su Dejun et al. Uninsurance, Underinsurance and Health Care Utilization in Mexico by US Border Residents. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health Vol 16(4):607–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff H, et al. Undocumented Migrants Lack Access to Pregnancy Care and Prevention. BMC Public Health 2008. (8)93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO sustainability health related targets. 2016. SDG Health and Health-Related Targets. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/EN_WHS2016_Chapter6.pdf

- 9.US department of Health and human services, Child Health USA 2013. Available at: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/chusa13/introduction.html

- 10.ACOG committee PB 95:2008, Anemia in pregnancy, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008. Vol 112 (1):201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.USPSTF Review. Screening for Iron Deficiency Anemia in Childhood and Pregnancy: Update of the 1996 U.S. Preventative Services Task Force Review, 2006. Available at: file:///C:/Users/megwh/Downloads/ironscrev.pdf [PubMed]

- 12.Garcia AS, Keyes DG. Life as an undocumented immigrant: How restrictive local immigration policies affect daily life. Center for American Progress; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes S, et al. The Impact of Local Immigration Enforcement Policies on the Health of Immigrant Hispanic/Latinos in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2015. Vol 105(2):329–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amnesty International. Deadly delivery: the maternal health care crisis in the USA. London (UK): Amnesty International Publications; 2010. Available at http://www.amnestyusa.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/deadlydelivery.pdf

- 15.MacDorman M et al. Recent Increases in the US Maternal Mortality Rate: Disentangling Trends from Measurement Issues. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016. Vol 128(3):447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antony KM, Hemarajata P, Chen J, et al. Generation and validation of a universal perinatal database and biospecimen repository: PeriBank. J Perinatol 2016. Vol 36:921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander GR & Kotelchuck M Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep 1996. Vol 111, 408–418; discussion 419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotelchuck M The Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index: its US distribution and association with low birthweight. Am J Public Health 1994. Vol 84, 1486–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017; Vol 167(4):268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu MC, et al. Elimination of public funding of prenatal care for undocumented immigrants in California: a cost/benefit analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000. Vol 182(1)233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown B Cutting public funding for undocumented immigrants’ prenatal care would raise the cost of neonatal care. Family Planning Perspective. 2000. Vol 32(3):145–147 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubard CA, Massing MW. Trends in emergency Medicaid expenditures for recent and undocumented immigrants. JAMA. 2007. Vol 297(10)1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bixby R Choosing our Words and Futures Wisely: Political Rhetoric and Prenatal Care Policy for Inclusion of Women with Undocumented Status. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2011. Vol 56 (2):91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi M, Livingston A. More than 400,000 Texans’ insurance at risk after Congress fails to renew CHIP. 2017. The Texas Tribune. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medicaid CHIP Funding. Medicaid.gov. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/chip/financing/index.html

- 26.Migration Policy Institute. Profile of the Unauthorized Population: United States, 2014. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/US

- 27.Guillory V, et al. Low birth weight in Kansas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2015. Vol 26(2)577–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loftus CT, et al. A Longitudinal Study of Changes in Prenatal Care Utilization Between First and Second Births and Low Birth Weight. 2015. Maternal and Child Health Journal. Vol 19(12)2627–2635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debiec KE, et al. Inadequate prenatal care and risk of preterm delivery among adolescents: a retrospective study over 10 years. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010. Vol 203(2):122–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.