Abstract

The field of human genomics has changed dramatically over time. Initial genomic studies were predominantly restricted to rare disorders in small families. Over the last decade, researches changed course from family-based studies and instead focused on common diseases and traits in populations of unrelated individuals. With further advancements in biobanking, computer science, electronic health record data, and more affordable high throughput genomics, we are experiencing a new paradigm in human genomic research. Rapidly changing technologies and resources now makes it possible to study thousands of diseases simultaneously at the genomic level. This review will focus on these advancements as scientists begin to incorporate phenome-wide strategies in human genomic research to understand the etiology of human disease and develop new drugs to treat them.

Keywords: phenome-wide association study, PheWAS, genome-wide association study, GWAS, biobank, drug development, pleiotropy, big data

A Genomic Perspective

We live in a rapidly advancing technological age driven by ever-increasing computational power. In genetics research, high throughput computing, high throughput genomics, and biobanking resources comprising “big data” have become increasingly important. The goal of this review is to describe the current trajectory of human genetic research in the context of advances in phenome-wide research; an innovative field of research that can often be compared to genome-wide research. However, before one can discuss future trajectories in human genomic research, it is always important to evaluate the trends of the past.

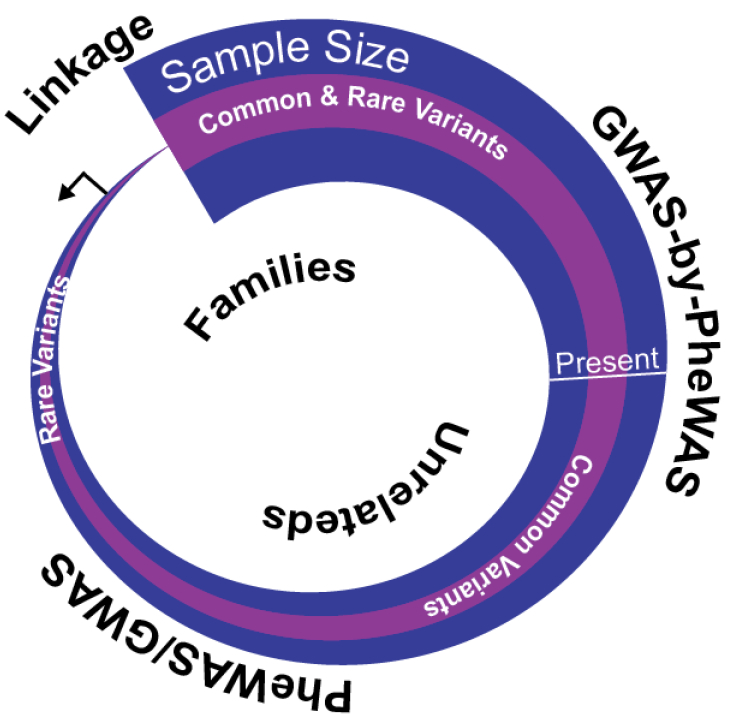

According to the Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man, there are nearly 4,000 genes with phenotype-causing variants [1, 2]. Most of these discoveries were made possible with family-based study designs which are effective in identifying rare variants with large effect sizes [3, 4]. Family-based study designs can include a variety of familial relationships (e.g., twins, sib-pairs, mother-father-child trios, and extended families). There are also a multitude of statistical tests that can be applied to family-based studies such as segregation and linkage analyses. Segregation analysis does not require genetic data but can be used to inform the likelihood a disease is heritable and provide insights on the disease’s genetic mode of inheritance. If a disease appears to be heritable and the mode of inheritance can be accurately defined, classical parametric linkage tests can identify regions of the genome that co-segregate with disease in families. These analyses are robust under population substructure and are useful for monogenic disorders. Linkage tests are less effective in the presence of locus heterogeneity, when the inheritance model is unknown, and for low penetrant variants, qualities often connected to complex diseases. An alternative to classical linkage analysis in family-based designs can include transmission disequilibrium tests. These tests can detect linkage in the presence of a genetic association and can have more statistical power in some instances as shown by Risch and Merikangas.[5] A significant challenge with any family-based study design is recruiting informative families to study the most interesting phenotypes. Over the last decade, studies like Risch and Merikangas,[5] advancements in high throughput genotyping, and ease of recruiting unrelated individuals, shifted human genomic research from family-based studies to studies of large numbers of unrelated individuals. More specifically, research groups have gravitated towards the genome-wide association study (GWAS) (Figure 1).

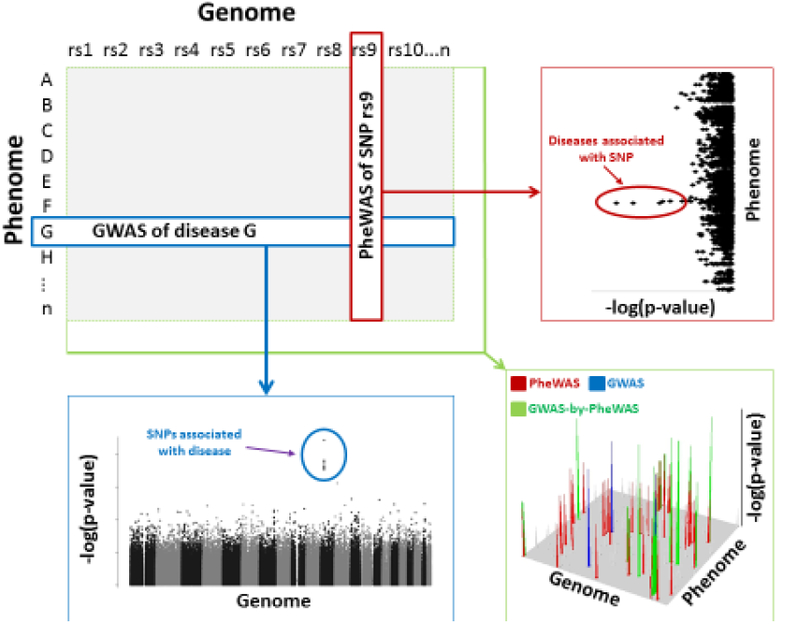

Figure 1 (Key Figure):

Schematic representation of a genome-wide association study (GWAS) (blue) and phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) (red) relative to a GWAS-by-PheWAS (green). Included are examples of corresponding results and significant findings.

One of the first GWASs published was in 2005 which described the genotyping of 96 cases with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and 50 unaffected controls [6]. This study, along with two others published simultaneously in Science[7, 8], was able to map a common variant in CFH that was associated with AMD, which validated previous findings first discovered by family-based linkage analyses [9–12]. This result supported a popular hypothesis that common traits are largely influenced by a few common variants [13–15] and highlighted the inherent strength of the GWAS technique to study populations of unrelated individuals. Since then, the GWAS technique has been highly effective in associating common variants to common diseases. As of 2018, GWASs have identified over 50,000 candidate Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)-disease/trait associations (P<1*10−5) [16–18]. Incidentally, all these GWAS results support an iteration of the common disease common variant hypothesis where many variants with weak effects cumulatively contribute to disease risk.[19, 20] Unfortunately, an unexpected shortcoming of the GWAS approach was the challenge in extracting biological inferences from GWAS results. Whereas family-based approaches are well suited to identify rare variants with large effects that often cause perturbations to protein coding sequence, most variants identified by GWAS are non-coding and may influence genes that are kilobases away from candidate variants. This challenge is further compounded by linkage disequilibrium (LD), a phenomenon where alleles non-randomly associate with one another at two or more loci in a population, making it more difficult to identify causative variants [18, 21].

To better understand human disease, impact of common variants with ever smaller effect sizes, account for rare variants, and to overcome stringent corrections for multiple testing, larger GWASs have been conducted. For example, the first GWAS of AMD described above evaluated 146 cases-controls and was able to identify one statistically significant signal [6]. Only 11 years later, the largest GWAS of AMD to date genotyped nearly 16,000 cases and 18,000 controls to identify 52 statistically significant and independent variants, including rare variants [22]. Such GWASs are not feasible without highly collaborative consortiums and still require significant expense in patient recruitment and genomic data acquisition. This is particularly relevant as next-generation sequencing technologies replace SNP array platforms. Using biobanks with pre-existing genomic and phenomic data may help expedite such studies.

Biobanks in Genomic Research

A biobank is a collection of stored biological specimens. This may include residual tissues from clinical care saved for legal purposes or collected directly for research. Arguably, one of the most valuable biobanks in genomic research has included material gathered from Centre d’Etude du Polymorphism Humain (CEPH) families [23]. Established in 1984, lymphocytes from CEPH families were collected as a reference set for human genome mapping. Lymphocytes were immortalized so DNA could be obtained in perpetuity. These DNAs were some of the first to be used for mapping the genome with microsatellites [24, 25], SNPs [26, 27], and at the single base-pair level [28, 29]. A significant advantage of a biobank is its use in future research; future research that may not have been conceivable when the samples were first banked. For example, the immortalized lymphocytes initially designed to maintain DNA stocks from CEPH families have been developed into model systems for quantitative trait loci mapping of epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic variants [30–33]. These cell lines have also been used as a model system to map drug response phenotypes [34–37]. What the CEPH biobank lacks, and many others like it, is a connection to extensive disease information necessary for mapping human traits.

With the computer age, extensive disease information can now be collected and stored in an electronic health record (EHR). An EHR can include diagnostic/billing codes, prescription records, laboratory results, clinical notes, family histories, images, and many other clinically relevant data. Clinical information in an EHR is often updated in real-time and does not require patient interactions via a research protocol beyond initial recruitment. Recognizing the importance of EHR data, scientists have created large DNA biobanks linked to extractable clinical data. Multiple examples of such biobanks exist including academic healthcare institutions aligned with the electronic MEdical Records and GEnomics (eMERGE) Network [38–40], UK-biobank [41, 42], and deCODE [43]. More recently, much larger biobanks linked to medical record data are at varying stages of development including the National Institute of Health “All of Us” project (formally known as Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program; >1 million participants) [44] and the Million Veteran Program (>1 million participants) [45]. EHR data can provide an efficient mechanism to identify cases and controls for disease-specific research. For example, it may take many years to recruit thousands of patients with type II diabetes. Conversely, it may take a fraction of the time to develop a type II diabetes prediction algorithm to identify cases and controls in an EHR-linked biobank based on type II diabetes diagnostic codes, type II diabetic medication records, and/or fasting glucose/HbA1c test results [46]. Replicating this algorithm in another EHR system is even faster, on the order of days to weeks, once the algorithm has been validated. With sufficient time and subject matter expertise, and depending on the complexity of the input data, these algorithms can be developed to parse cases from controls with favorable predictive values. In the future, machine learning techniques in a complex EHR environment may expedite algorithm development and reduce the need for subject matter expertise.[47] Lastly, EHR-linked biobanks with pre-existing genomic data can further reduce project costs and can be repurposed to study many other diseases (Figure 2).

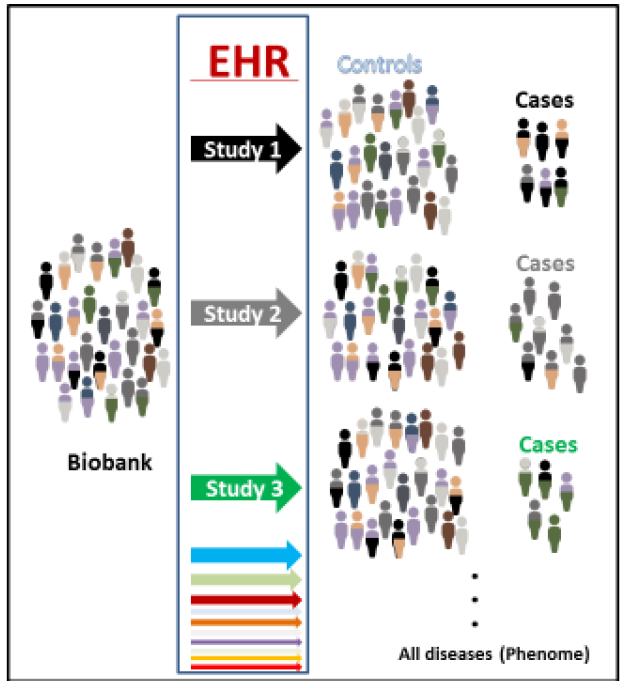

Figure 2:

An example of a biobank linked to an electronic health record (EHR). Different colors represent a heterogeneous population that can be separated (by color) into different case control groupings to study specific diseases or all diseases for PheWAS.

Whereas the extractable EHR data can be the greatest asset to a biobank, it is also its greatest limitation. For example, diagnostic codes, most notably the International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes that can be used to identity patients with a specific disease [e.g., diabetes code(s); ICD9 250 or ICD10 E08-E13], are used for billing purposes in the United States. These codes can have limited phenotypic resolution, change over time, and may be used differently across institutions and in clinical practice [48]. Likewise, medication data in an EHR can be incomplete as there are often disagreements between what is prescribed, what prescription is filled, and whether the patient is compliant. An EHR may also not list medications/supplements self-administered by a patient. Another limitation of an EHR is its inherent link to the stability of the patient population. Patients that are transient or seek care at multiple healthcare systems can leave significant gaps in the clinical record, particularly if each institution uses differing EHR systems. Yet, even with these challenges, EHR data has proven repeatedly to be an efficient data source for phenotypic information for genomic research [38–40]. Importantly, EHR data, and the biobanks that are linked to EHR data, has been invaluable for phenome-wide association studies (PheWASs).

A Phenomic Perspective

In classical genetics, there are two main strategies. “Forward” genetics is a phenotype-to-genotype strategy that is epitomized in human genomic research by family-based (e.g., linkage studies) and non-family-based studies of unrelated individuals (e.g., GWAS) (Figure 1). “Reverse” genetics is a genotype-to-phenotype strategy and has historically been limited to model organisms (e.g., mouse knockouts). In 2010, Denny et al. conducted the first proof-of-principle reverse genetic study in humans and coined it a PheWAS [49] (Figure 1). This study focused on five disease associated SNPs that were genotyped in their EHR-linked biobank. Case-control status for a wide variety of disease phenotypes were extracted from the medical record. In simplistic terms, individuals with an ICD code, or a combination of relevant codes, were defined as cases for that disease whereas those without any relevant codes were defined as unaffected controls for that disease. This was repeated for each ICD code to generate 776 different case-control groups that defined the phenome. Each SNP was then associated across the phenome (Figure 2). In most instances, and even with all the limitations of EHR data, the expected associations that were previously identified utilizing forward genetics (i.e., GWAS) could be rediscovered by PheWAS. Other groups have since provided additional proof-of-principle that reverse genetic screens in humans can rediscover known associations previously identified by GWAS [50–55]. More importantly, PheWAS can provide novel insights not readily attainable by forward genetic strategies.

As stated previously, reverse genetic approaches were primarily limited to model systems. For example, if a researcher wanted to understand the genetic contribution to pathophysiology, he/she could apply genome editing techniques to knock out a specific gene in a model system (e.g., mouse) and evaluate the model for differential outcomes. For obvious ethical reasons, a reverse genetic screen by genome editing should not be done in humans. However, a similar experiment can be accomplished in human populations utilizing what nature has already provided. For example, groups have conducted systematic PheWASs on common loss-of-function variants. These screens have rediscovered an association between cholesterol levels and a nonsense SNP in LPL (rs328) [56, 57], implicated a deleterious variant in KCNH2 with acquired hypothyroidism [56], and discovered that a polymorphic gene deletion and duplication of SULT1A1 may be related to common allergies [58]. Whereas most of the PheWASs have focused on common variants, others have begun to utilize sequencing data to study rare loss-of-function variants [59], variants that may have larger effects sizes compared to common variants. To give homage presumably to reverse genetic models, one group that is systematically evaluating these rare loss-of-function variants calls their study the “Human Knockout Project” [60].

A unique quality of the PheWAS technique is its capacity to evaluate cross-phenotype associations or pleiotropy [61–63]. There are numerous examples where genetic variants overlap different phenotypes. For example, multiple GWASs have implicated FTO with body mass index (BMI) and type II diabetes [16, 17]. A PheWAS focused on FTO variants rediscovered the same associations but also implicated other conditions not previously evaluated by GWAS including sleep apnea [52]. PheWAS can not only characterize pleiotropic effects and capture novel associations but is uniquely capable of evaluating confounding effects in the phenotypic information. As it relates to the PheWAS of FTO, results demonstrate that the genetic effect of type II diabetes is partially independent from BMI but sleep apnea is not [52].

The most pleiotropic region of the human genome may include the MHC region on chromosome 6 that encodes HLA genes. For example, the first PheWAS by Denny et al. provided evidence that HLA-DRB1, a gene previously implicated with multiple sclerosis [64], is also associated with risk for “erythematous conditions” [49]. This novel association was independently replicated by another PheWAS and further refined to include rosacea [65]. Two years later, multiple HLA genes, including HLA-DRB1, were identified to be associated with rosacea by the first GWAS on this condition [66]. Comprehensive evaluations of all HLA genes by PheWAS have further emphasized the capacity of the PheWAS technique to quantify pleiotropy in this important region of the human genome [67–69].

Pleiotropy identified by PheWAS may help in drug development. If there is evidence that “Disease A” and “Disease B” share a common genetic etiology through a pleiotropic variant, then it could be hypothesized that “Drug X” used to treat “Disease A” may be repurposed to treat “Disease B” (Figure 3). In the example of FTO variants that are associated with type II diabetes, obesity, and sleep apnea [52], one could hypothesize that anti-diabetic drugs that also result in weight loss (e.g., SGLT2 inhibitors) may be effective in treating BMI induced sleep apnea in type II diabetes patients.

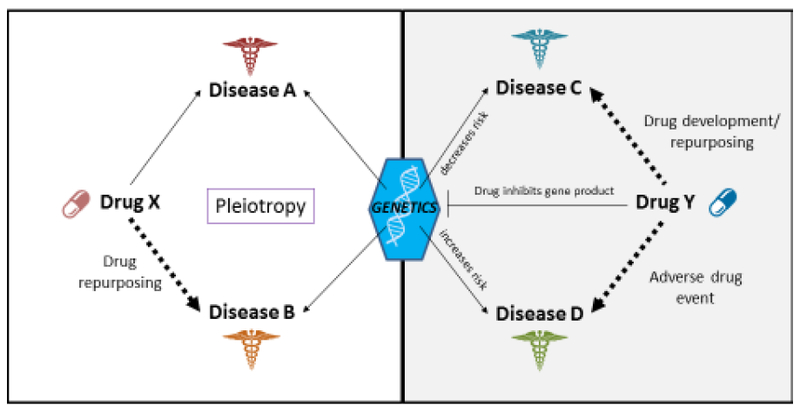

Figure 3:

An illustration on how PheWAS data can help with drug development/repurposing. Left side shows that if Drug X is effective in treating Disease A, Drug X may be repurposed to treat Disease B if both Disease A and Disease B share a common genetic etiology as evident by pleiotropy. Right side shows that if Drug Y inhibits a gene product and a loss-of-function variant in a gene decreases risk for Disease C, then Drug Y may be used to treat Disease C. If the same functional variant increases risk for Disease D, Disease D may be an adverse event when treating with Drug Y.

Even though PheWAS is uniquely capable of identifying pleiotropy, PheWAS data will likely prove useful in other ways during drug development. A PheWAS can show that “Disease C” is associated with a gene whose translated product can be targeted by “Drug Y” [70–73]. In this instance, “Disease C” could represent an indication for “Drug Y” (Figure 3). A recent example of genomic data describing such a relationship includes cholesterol-lowering PCSK9 inhibitors. This drug class was developed after it was shown that individuals with loss-of-function PCSK9 variants result in low circulating LDL levels [74–76]. Conducting follow-up PheWASs on functional PCSK9 variants may help identify additional targets for PCSK9 inhibitors. Moreover, such PheWAS data could also identify adverse drug events for PCSK9 inhibitors [77]. To use the example of “Drug Y” described above, if “Disease D” is associated with the same gene as “disease C” but with an opposite direction of effect, than “Disease D” may result in an adverse event if treated with “drug Y” (Figure 3).

Because of its potential value, pharmaceutical companies are heavily investing in GWASs and PheWASs to reduce costs and risks during drug development. Direct-to-consumer genomic companies (e.g., 23andMe) have adapted their business model to allow pharmaceutical companies to gain access to genomic and phenomic data from consenting customers for drug development [78, 79]. Given their success with their PCSK9 inhibitor, Regeneron has already exome sequenced over 50,000 participants from an EHR-linked biobank from Geisinger Health [80] to help with the drug discovery pipeline. Likewise, Regeneron and a consortium of other pharmaceutical companies are investing over $100 million to sequence 500,000 individuals in the UK-Biobank [81]. Whereas these partnerships may lead to new and effective treatments, they also introduce ethical concerns regarding data use when profiting from participant data. Regardless, with future trajectories pointing to larger datasets, a great deal will be learned in human genomic research.

A Future Perspective

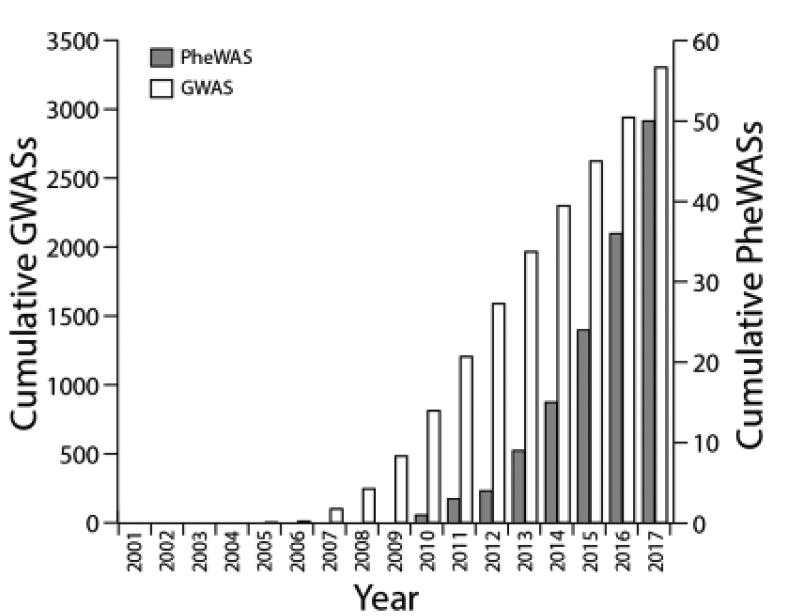

Before GWAS, there were countless candidate SNP association studies. Candidate SNP studies then evolved to candidate gene studies that evaluated multiple variants in a single gene, then further progressed to the study of multiple variants in multiple genes (e.g., multiple genes in a common biological pathway). This progression was made possible in part by array technologies along with SNP cataloguing efforts (e.g., dbSNP [82] and HapMap Project [83]). It is expected that advancements in PheWAS will take a similar but perhaps not as linear a path. This is evident by the first PheWASs starting with candidate SNP studies [49] then quickly followed by candidate gene [52, 55, 84, 85] and multiple gene studies [67, 68, 86–88]. Although the PheWAS community is taking a similar path that other scientists took to reach GWAS, growth in PheWAS will always be limited by the availability of phenomic data. There are only a limited number of institutions/groups that currently capture extensive phenomic data through ICD coding or by other data sources such as extensive epidemiologic [50, 89–91], rich text [54, 58], or biometric/laboratory data [69]. Even fewer groups have DNA linked to such data. Even when all necessary data is available, institutional politics/culture can make it difficult for one investigator to study all diseases simultaneously, especially when colleagues use the same data to carve out their own disease specific research. It is expected that the progression of PheWAS will be muted compared to the growth observed in GWAS. This is evident in the literature, as there were 50 PheWASs published between the first proof-of-concept PheWAS [25] and at end of 2017 according to manual inspection of PubMed results using the search-term “PheWAS.” Even if this PubMed search identified half of all published PheWASs, this still dwarfs in comparison to 1,588 GWASs published over a same eight year span according to the GWAS Catalogue [16–18] (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Cumulative number of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) [16–18] (white) and phenome-wide association studies (PheWASs) (grey) published over time.

Eventually, the GWAS and PheWAS communities will reach an inflection point. This inevitable event, which is already occurring (http://geneatlas.roslin.ed.ac.uk/ and http://pheweb.sph.umich.edu/) [69], will happen when thousands of diseases are studied by GWAS and millions of variants are studied by PheWAS in a single experiment; a GWAS-by-PheWAS (Figure 1). Conducting and interpreting a GWAS-by-PheWAS will have unique challenges. Statistical significance at the genome-wide level is often defined by P<5*10−8 [5, 21, 92]. In a PheWAS, adjusting for multiple comparison testing can be more complicated. Not only will there be correlations between closely related phenotypes much like two nearby SNPs in LD, distant diseases may also be correlated due to disease comorbidities (e.g., heart disease and diabetes). Regardless, when using a Bonferroni correction commonly applied during PheWAS, statistical significance for studying 5,000 phenotypes would be defined by P<1*10−5. In a GWAS-by-PheWAS, where every variant is associated with every phenotype, statistical significance could be defined by P<5*10−13. With future biobanks expected to include over 1 million participants linked to extensive phenotypic data (e.g., an EHR), a P>5*10−13 may not be insurmountable for common variants that are associated with common conditions. It is even expected that rare conditions with a disease prevalence of 0.1% (~1,000 cases in a population of 1 million participants) can also be evaluated but challenges will remain when evaluating rare variants and variants with weak effects.

With ever larger PheWASs and GWASs, disease misclassification may amplify false positives or lead to incorrect conclusions. For example, if there are 100,000 cases defined for a given disease but the misclassification rate for that disease is 1%, signals from the 1,000 misclassified cases could reach statistical significance. These associations would likely have weak effects, but it will be difficult to parse true associations from associations driven by other diseases. In addition to challenges with misclassification, population substructure may also lead to additional challenges under large sample sizes.[93] In a well-designed study, population structure can be accounted for by incorporating principal component analysis (PCA) into the statistical model.[94, 95] If a study population is large enough, it is possible subpopulations may exist that may not be accounted for in the first few PCAs. If a disease is linked to that subpopulation, population-associated alleles may be confused with disease-associated variants. Conversely, when evaluating rare variants in large sample sizes, adjusting for PCAs may adjust out the effect of the rare variant and reduce power.

Another challenge with ever larger datasets that are particularly relevant for PheWAS includes privacy issues. Manuscripts in themselves make summary data public by disclosing case/control counts, p-values, odds ratios and other non-individual level information. Conversely, funding agencies and journal publishing groups often require de-identified individual level data to be made public by depositing such data into access controlled databases (e.g., dbGAP). Genetic data by itself can be identifiable [96] but often lacks a naming source. When a naming source is available, genetic data is not only identifiable to the individual who provided the DNA, but also with relatives [97] as exemplified recently by the “Golden State Killer” case in the United States.[98, 99] Combinations of phenotypic data provided at an individual level could present another pronounced degree of identifiable information. Hypothetically, a male (50% of population) born with a club foot (~0.1% of all live births) [100] who has been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (~0.1% of individuals) [101], would represent a unique combination of variables using only three outwardly visible traits (~5 per 10 million individuals). With advances in computer science through machine learning and image analysis [102], the probability of some participants being identifiable could be compounded as people freely and unwittingly share health and genetic information through social media and crowd sourcing[103, 104]. To this end, lawmakers, regulators, and scientists need to continue to find ways to make individual level genomic and phenomic data available to the public but in a controlled and protected environment.

The field of human genetics has increasingly become ever more interdisciplinary through computer science, informatics, and statistics. Future studies that include GWAS-by-PheWAS data will represent billions of association results and terabytes of data that will need to be stored in a queryable data structure likely through big-data solutions. New methods will be required to evaluate phenomic data on top of genomic, proteomic, transcriptomic, and other -omic data. The complexities of such data, in combination with genome editing, single cell analysis, and other molecular techniques, may not only provide important insights into how human genetics influences human disease but also influences biological processes defined at the organ, tissue, and cellular level.

Regardless of the layers of data generated by GWAS, PheWAS, or GWAS-by-PheWAS, these studies are currently and predominantly rooted in populations of unrelated individuals. As mentioned in the beginning, a great deal has been historically learned in human genetics through family-based study designs. It is conceivable that if populations become large enough, especially in a healthcare system servicing a stable patient population, large familial pedigrees may be captured and used for genomic study. For example, approximately 20% of 2.6 million current and historic patients of Marshfield Clinic (Marshfield, WI) that serves a predominantly rural population can be placed in family pedigrees using readily available data in an EHR. Such pedigrees may be applied to phenome-wide research [105] and may be incorporated into existing biobanks for genetic association testing even if some family members are not directly genotyped [106]. If large populations of families are linked to extensive phenotypic and genomic data, human genomic research may come full circle back to family-based study designs [107] which will allow researchers to study thousands of human diseases in relationship to variants with a wide spectrum of allele frequencies and effect sizes (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

A simplified illustration of the historical and future progression of human genomic research starting with small family-based studies (e.g., linkage studies) to ever larger studies of unrelated individuals (e.g., GWAS, PheWAS, and GWAS-by-PheWAS). As sample size (purple) becomes exceptionally large, future studies may include population-based family studies to identify increasing number of trait associated variants (pink).

Concluding Remarks

With the computer age, technology is advancing at an ever increasing rate. Since genomic and healthcare research is progressively intertwined with technology, it is of my opinion that the field of human genomics in the 21st century is like an unstoppable boulder rolling downhill. With high throughput computing, big data, along with decreasing cost for whole-genome sequencing, society will soon expect genomic data to be incorporated into standard of care as part of precision medicine. Researchers will then have access to virtual DNA biobanks of millions of individuals that link together extensive genomic and phenomic data. When this inevitable future happens, there will be new challenges in data management, privacy issues, and clinical care but will also dramatically change how human genomic research is conducted as scientists search to understand and treat human disease using a combination of phenome-wide and genome-wide strategies (See Outstanding Questions).

Trends Box:

Human genetic research has morphed from studying rare disorders in families to common conditions in populations of unrelated individuals.

Advances in biobanking, computer science, and electronic health records linked to real life clinical data have allowed for the study of thousands of diseases simultaneously via phenome-wide association studies.

As genomic studies continue to grow in size and scale, both rare and common diseases may be studied simultaneously at the genome-wide and phenome-wide level which may help understand the genetic causes of human disease and ways to treat them.

Outstanding Questions Box:

If genomic data is collected on a large scale via clinical care or research, and such data is linked to extensive phenotypic information through an electronic health record, how will this data be used for research?

What will be the technical and practical challenges in human genomic research when study populations reach millions of individuals?

How will phenomic data be combined and used with genomic and other layers of omics data to better understand and treat human disease?

Glossary Box:

- Biobank:

A tissue repository collected via clinical care and/or research.

- EHR – Electronic Health Record:

An electronic data repository of health records collected via routine clinical care.

- GWAS – Genome-Wide Association Study:

A general study design or statistical methods intended to identify genetic variants associated with a phenotype. In a case-control study, each variate is evaluated to determine if the allele frequency is different in one group compared to the other. Although not exclusive, GWASs are often applied to populations of unrelated individuals.

- LD – Linkage Disequilibrium:

A measure of correlation within a population between two genetic markers. Genetic variants are in LD most often when two loci are physically in close proximity to one another. Because they are close together, few recombination events occur between the markers and they co-segregate during meiosis.

- Linkage Analysis:

A family-based statistical method that evaluates whether genetic markers co-segregate with disease in families. There are numerous types of linkage analyses that can be applied to different family structures and disease models.

- PCA – Principal Component Analysis:

A statistical method often applied in epidemiologic research to account for population substructures.

- PheWAS – Phenome-Wide Association Study:

A general study design or statistical method intended to identify phenotypes associated with a genotype. PheWASs often rely on in-depth phenotypic data, including EHR or epidemiologic data, to define case-control status for a wide variety of phenotypes.

- SNP – Single Nucleotide Polymorphism:

One of the most common types of genetic variation in the human genome that results in a single nucleotide point change in DNA sequence. SNPs are often measured for mapping human diseases

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.OMIM (2018) http://www.omim.org/, (accessed March 6 2018).

- 2.Amberger JS et al. (2015) OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM(R)), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res 43 (Database issue), D789–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manolio TA et al. (2009) Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461 (7265), 747–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonarakis SE and Beckmann JS (2006) Mendelian disorders deserve more attention. Nat Rev Genet 7 (4), 277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risch N and Merikangas K (1996) The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science 273 (5281), 1516–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein RJ et al. (2005) Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308 (5720), 385–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards AO et al. (2005) Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science 308 (5720), 421–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haines JL et al. (2005) Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science 308 (5720), 419–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majewski J et al. (2003) Age-related macular degeneration--a genome scan in extended families. Am J Hum Genet 73 (3), 540–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weeks DE et al. (2004) Age-related maculopathy: a genomewide scan with continued evidence of susceptibility loci within the 1q31, 10q26, and 17q25 regions. Am J Hum Genet 75 (2), 174–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abecasis GR et al. (2004) Age-related macular degeneration: a high-resolution genome scan for susceptibility loci in a population enriched for late-stage disease. Am J Hum Genet 74 (3), 482–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyengar SK et al. (2004) Dissection of genomewide-scan data in extended families reveals a major locus and oligogenic susceptibility for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 74 (1), 20–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lander ES (1996) The new genomics: global views of biology. Science 274 (5287), 536–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakravarti A (1999) Population genetics--making sense out of sequence. Nat Genet 21 (1 Suppl), 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich DE and Lander ES (2001) On the allelic spectrum of human disease. Trends Genet 17 (9), 502–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welter D et al. (2014) The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res 42 (Database issue), D1001–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacArthur J et al. (2017) The new NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS Catalog). Nucleic Acids Res 45 (D1), D896–D901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdett T et al. The NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies. www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas, (accessed January 1 2018).

- 19.Pritchard JK and Cox NJ (2002) The allelic architecture of human disease genes: common disease-common variant…or not? Hum Mol Genet 11 (20), 2417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y et al. (2018) Estimation of complex effect-size distributions using summary-level statistics from genome-wide association studies across 32 complex traits. Nat Genet. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy MI et al. (2008) Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet 9 (5), 356–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritsche LG et al. (2016) A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat Genet 48 (2), 134–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prescott SM et al. (2008) From linkage maps to quantitative trait loci: the history and science of the Utah genetic reference project. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 9, 347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. (1992).A comprehensive genetic linkage map of the human genome. NIH/CEPH Collaborative Mapping Group. Science 258 (5079), 67–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen D et al. (1993) A first-generation physical map of the human genome. Nature 366 (6456), 698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinds DA et al. (2005) Whole-genome patterns of common DNA variation in three human populations. Science 307 (5712), 1072–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers S et al. (2005) A fine-scale map of recombination rates and hotspots across the human genome. Science 310 (5746), 321–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abecasis GR et al. (2010) A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467 (7319), 1061–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abecasis GR et al. (2012) An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491 (7422), 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birney E et al. (2007) Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447 (7146), 799–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spielman RS et al. (2007) Common genetic variants account for differences in gene expression among ethnic groups. Nat Genet 39 (2), 226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lappalainen T et al. (2013) Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature 501 (7468), 506–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garge N et al. (2010) Identification of quantitative trait loci underlying proteome variation in human lymphoblastoid cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 9 (7), 1383–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W and Dolan ME (2009) Use of cell lines in the investigation of pharmacogenetic loci. Curr Pharm Des 15 (32), 3782–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalari KR et al. (2010) Copy number variation and cytidine analogue cytotoxicity: a genome-wide association approach. BMC Genomics 11, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shukla SJ and Dolan ME (2005) Use of CEPH and non-CEPH lymphoblast cell lines in pharmacogenetic studies. Pharmacogenomics 6 (3), 303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niu N et al. (2016) Metformin pharmacogenomics: a genome-wide association study to identify genetic and epigenetic biomarkers involved in metformin anticancer response using human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Hum Mol Genet 25 (21), 4819–4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarty CA et al. (2011) The eMERGE Network: a consortium of biorepositories linked to electronic medical records data for conducting genomic studies. BMC Med Genomics 4, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gottesman O et al. (2013) The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network: past, present, and future. Genet Med 15 (10), 761–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kho AN et al. (2011) Electronic medical records for genetic research: results of the eMERGE consortium. Sci Transl Med 3 (79), 79re1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sudlow C et al. (2015) UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 12 (3), e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen NE et al. (2014) UK biobank data: come and get it. Sci Transl Med 6 (224), 224ed4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hakonarson H et al. (2003) deCODE genetics, Inc. Pharmacogenomics 4 (2), 209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins FS and Varmus H (2015) A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 372 (9), 793–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaziano JM et al. (2016) Million Veteran Program: A mega-biobank to study genetic influences on health and disease. J Clin Epidemiol 70, 214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kho AN et al. (2012) Use of diverse electronic medical record systems to identify genetic risk for type 2 diabetes within a genome-wide association study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 19 (2), 212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hripcsak G and Albers DJ (2013) Next-generation phenotyping of electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 20 (1), 117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hebbring SJ (2014) The challenges, advantages and future of phenome-wide association studies. Immunology 141 (2), 157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denny JC et al. (2010) PheWAS: demonstrating the feasibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover gene-disease associations. Bioinformatics 26 (9), 1205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pendergrass SA et al. (2013) Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) for detection of pleiotropy within the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Network. PLoS Genet 9 (1), e1003087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Denny JC et al. (2013) Systematic comparison of phenome-wide association study of electronic medical record data and genome-wide association study data. Nat Biotechnol 31 (12), 1102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cronin RM et al. (2014) Phenome-wide association studies demonstrating pleiotropy of genetic variants within FTO with and without adjustment for body mass index. Front Genet 5, 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hall MA et al. (2014) Detection of pleiotropy through a Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) of epidemiologic data as part of the Environmental Architecture for Genes Linked to Environment (EAGLE) study. PLoS Genet 10 (12), e1004678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hebbring SJ et al. (2015) Application of clinical text data for phenome-wide association studies (PheWASs). Bioinformatics 31 (12), 1981–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diogo D et al. (2015) TYK2 protein-coding variants protect against rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity, with no evidence of major pleiotropic effects on nonautoimmune complex traits. PLoS One 10 (4), e0122271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verma A et al. (2016) eMERGE Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS) identifies clinical associations and pleiotropy for stop-gain variants. BMC Med Genomics 9 Suppl 1, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye Z et al. (2015) Phenome-wide association studies (PheWASs) for functional variants. Eur J Hum Genet 23 (4), 523–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J et al. (2017) Relationship of SULT1A1 copy number variation with estrogen metabolism and human health. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 174, 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verma SS et al. (2018) Rare variants in drug target genes contributing to complex diseases, phenome-wide. Sci Rep 8 (1), 4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saleheen D et al. (2017) Human knockouts and phenotypic analysis in a cohort with a high rate of consanguinity. Nature 544 (7649), 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tyler AL et al. (2016) The detection and characterization of pleiotropy: discovery, progress, and promise. Brief Bioinform 17 (1), 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pendergrass SA and Ritchie MD (2015) Phenome-Wide Association Studies: Leveraging Comprehensive Phenotypic and Genotypic Data for Discovery. Curr Genet Med Rep 3 (2), 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pendergrass SA et al. (2015) Phenome-Wide Association Studies: Embracing Complexity for Discovery. Hum Hered 79 (3–4), 111–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baranzini SE and Oksenberg JR (2017) The Genetics of Multiple Sclerosis: From 0 to 200 in 50 Years. Trends Genet 33 (12), 960–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hebbring SJ et al. (2013) A PheWAS approach in studying HLA-DRB1*1501. Genes Immun 14 (3), 187–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang ALS et al. (2015) Assessment of the genetic basis of rosacea by genome-wide association study. J Invest Dermatol 135 (6), 1548–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J et al. (2016) Phenome-wide association study maps new diseases to the human major histocompatibility complex region. J Med Genet 53 (10), 681–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karnes JH et al. (2017) Phenome-wide scanning identifies multiple diseases and disease severity phenotypes associated with HLA variants. Sci Transl Med 9 (389). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verma A et al. (2018) PheWAS and Beyond: The Landscape of Associations with Medical Diagnoses and Clinical Measures across 38,662 Individuals from Geisinger. Am J Hum Genet. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rastegar-Mojarad M et al. (2015) Opportunities for drug repositioning from phenome-wide association studies. Nat Biotechnol 33 (4), 342–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robinson JR et al. (2017) Genome-wide and Phenome-wide Approaches to Understand Variable Drug Actions in Electronic Health Records. Clin Transl Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roden DM (2017) Phenome-wide association studies: a new method for functional genomics in humans. J Physiol 595 (12), 4109–4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Versel N (2018) Vanderbilt Spins Out Nashville Biosciences to Offer BioVU, PheWAS Services to Pharma. https://www.genomeweb.com/informatics/vanderbilt-spins-out-nashville-biosciences-offer-biovu-phewas-services-pharma#.WsUlmq3rtkc, (accessed 4/4/2008 2018).

- 74.Zhao Z et al. (2006) Molecular characterization of loss-of-function mutations in PCSK9 and identification of a compound heterozygote. Am J Hum Genet 79 (3), 514–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roth EM et al. (2012) Atorvastatin with or without an antibody to PCSK9 in primary hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 367 (20), 1891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elguindy A and Yacoub MH (2013) The discovery of PCSK9 inhibitors: A tale of creativity and multifaceted translational research. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2013 (4), 343–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jerome RN et al. (2018) Using Human ‘Experiments of Nature’ to Predict Drug Safety Issues: An Example with PCSK9 Inhibitors. Drug Saf 41 (3), 303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petrone J (2017) 23andMe wades further into drug discovery. Nat Biotechnol 35 (10), 897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mason M et al. (2017) Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing and Orphan Drug Development. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 21 (8), 456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abul-Husn NS et al. (2016) Genetic identification of familial hypercholesterolemia within a single U.S. health care system. Science 354 (6319). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Herper M (2018) Drug Company Consortium To Sequence The Genes Of 500,000 Britons Over Next Two Years. https://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewherper/2018/01/08/drug-company-consortium-to-sequence-the-genes-of-500000-britons-over-next-two-years/, (accessed 2/1/2018 2018).

- 82.Sherry ST et al. (1999) dbSNP-database for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other classes of minor genetic variation. Genome Res 9 (8), 677–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.(2003) The International HapMap Project. Nature 426 (6968), 789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Denny JC et al. (2011) Variants near FOXE1 are associated with hypothyroidism and other thyroid conditions: using electronic medical records for genome- and phenome-wide studies. Am J Hum Genet 89 (4), 529–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Polimanti R et al. (2017) Phenome-wide association study for CYP2A6 alleles: rs113288603 is associated with hearing loss symptoms in elderly smokers. Sci Rep 7 (1), 1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shameer K et al. (2014) A genome- and phenome-wide association study to identify genetic variants influencing platelet count and volume and their pleiotropic effects. Hum Genet 133 (1), 95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ehm MG et al. (2017) Phenome-wide association study using research participants’ self-reported data provides insight into the Th17 and IL-17 pathway. PLoS One 12 (11), e0186405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klarin D et al. (2017) Genetic analysis in UK Biobank links insulin resistance and transendothelial migration pathways to coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 49 (9), 1392–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pendergrass SA et al. (2011) The use of phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS) for exploration of novel genotype-phenotype relationships and pleiotropy discovery. Genet Epidemiol 35 (5), 410–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Verma SS et al. (2016) PHENOME-WIDE INTERACTION STUDY (PheWIS) IN AIDS CLINICAL TRIALS GROUP DATA (ACTG). Pac Symp Biocomput 21, 57–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moore CB et al. (2015) Phenome-wide Association Study Relating Pretreatment Laboratory Parameters With Human Genetic Variants in AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocols. Open Forum Infect Dis 2 (1), ofu113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Khoury MJ and Yang Q (1998) The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases: an epidemiologic perspective. Epidemiology 9 (3), 350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marchini J et al. (2004) The effects of human population structure on large genetic association studies. Nat Genet 36 (5), 512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Price AL et al. (2006) Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 38 (8), 904–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Freedman ML et al. (2004) Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat Genet 36 (4), 388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gymrek M et al. (2013) Identifying personal genomes by surname inference. Science 339 (6117), 321–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Erlich Y and Narayanan A (2014) Routes for breaching and protecting genetic privacy. Nat Rev Genet 15 (6), 409–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Phillips C (2018) The Golden State Killer investigation and the nascent field of forensic genealogy. Forensic Sci Int Genet 36, 186–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Syndercombe Court D (2018) Forensic genealogy: Some serious concerns. Forensic Sci Int Genet 36, 203–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dobbs MB and Gurnett CA (2009) Update on clubfoot: etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467 (5), 1146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dilokthornsakul P et al. (2016) Multiple sclerosis prevalence in the United States commercially insured population. Neurology 86 (11), 1014–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Claes P et al. (2014) Modeling 3D facial shape from DNA. PLoS Genet 10 (3), e1004224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yuan J et al. (2018) DNA.Land is a framework to collect genomes and phenomes in the era of abundant genetic information. Nat Genet 50 (2), 160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kaplanis J et al. (2018) Quantitative analysis of population-scale family trees with millions of relatives. Science 360 (6385), 171–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Polubriaginof FCG et al. (2018) Disease Heritability Inferred from Familial Relationships Reported in Medical Records. Cell 173 (7), 1692–1704 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Huang X et al. (2018) Applying family analyses to electronic health records to facilitate genetic research. Bioinformatics 34 (4), 635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Staples J et al. (2018) Profiling and Leveraging Relatedness in a Precision Medicine Cohort of 92,455 Exomes. Am J Hum Genet 102 (5), 874–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]