Abstract

Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile causes severe diarrheal disease that is directly associated with antibiotic use and resistance. Although C. difficile demonstrates intrinsic resistance to many antimicrobials, few genetic mechanisms of resistance have been characterized in this pathogen. In this study, we investigated the putative resistance factor, CD1240 (VanZ1), an ortholog of the teicoplanin resistance factor, VanZ, of Enterococcus faecium. In C. difficile, the vanZ1 gene is located within the skin element of the sporulation factor σK, which is excised from the mother cell compartment during sporulation. This unique localization enabled us to create a vanZ1 deletion mutant by inducing excision of the skin element. The Δskin mutant exhibited moderately decreased resistance to teicoplanin and had small effects on growth in some other cell-surface antimicrobials tested. Examination of vanZ1 expression revealed induction of vanZ1 transcription by the antimicrobial peptide LL-37; however, LL-37 resistance was not impacted by VanZ1, and none of the other tested antimicrobials induced vanZ1 expression. Further, expression of vanZ1 via an inducible promoter in the Δskin mutant restored growth in teicoplanin. These results demonstrate that like the E. faecium VanZ, C. difficile VanZ1 contributes to low-level teicoplanin resistance through an undefined mechanism.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, vanZ, teicoplanin, vancomycin, glycopeptides, antimicrobial resistance

INTRODUCTION

Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (1). Standard treatments for C. difficile infection (CDI) include the antibiotics metronidazole, vancomycin, and fidaxomicin in the United States, and also teicoplanin in Europe. (2–5). Although the majority of C. difficile strains remain sensitive to vancomycin by clinical testing (6, 7), the possibility of vancomycin resistance in this pathogen remains a threat to successful treatment.

In bacteria, glycopeptide resistance is frequently conferred by one of several classes of cell wall modifications encoded by the van resistance gene clusters (8–10). Each class of van genes alters the D-Ala-D-Ala peptidoglycan terminus, which is the binding site of vancomycin. The vancomycin resistance classes VanA, VanB, VanD, VanM, and possibly VanF, replace the terminal D-Ala with D-Lac (11–15), whereas classes VanC, VanE, VanG, and VanL replace the terminal D-Ala with D-Ser (16–19). Both the D-Lac and D-Ser modifications decrease the affinity of vancomycin for the new peptidoglycan termini (20, 21). Only the resistance classes VanA and VanD have been linked with both vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance (12, 22). Of these classes, the VanA gene cluster is the best characterized. The VanA operon typically consists of the genes vanRSHAXYZ, where VanRS are an autoregulatory vancomycin-responsive two-component system (23), VanH and VanA are the enzymes responsible for the addition of D-Lac to peptidoglycan (20, 24), VanX cleaves remaining D-Ala-D-Ala termini (25), VanY is a non-essential D,D-carboxypeptidase (26), and VanZ encodes a protein of unknown function (8). Although the specific function of VanZ remains unknown, VanZ increases teicoplanin resistance in Enterococcus faecium, but has no impact on vancomycin resistance (27).

Several van gene orthologues have been identified in the C. difficile genome (28). Of these, only the vanG-like cluster has been studied to date (29–31). These studies indicated that expression of the vanG-like cluster is induced by vancomycin, but these genes do not confer significant vancomycin resistance (29, 31). Whether any of the other van-like genes in C. difficile confer vancomycin resistance is unknown.

In this study, we investigated a predicted vanZ-like gene encoded in the C. difficile genome to determine if it plays a role in antimicrobial resistance. This putative vanZ gene, CD630_12400 (CD1240), was previously identified as a component within the skincd element in C. difficile (32). To investigate whether CD1240 contributes to sub-clinical glycopeptide (vancomycin or teicoplanin) resistance, we created a CD1240 deletion mutant by excising the skin element from vegetative cells, and tested the growth and survival of this strain in the presence of a variety of antimicrobials. We found that CD1240 contributes to low-level teicoplanin resistance but does not substantially impact resistance to vancomycin or other cell surface-acting antimicrobials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli was grown aerobically at 37°C in LB medium (33). 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Cayman Chemical Company) and 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to cultures as necessary. C. difficile was grown anaerobically at 37°C as previously described (34). C. difficile was grown in brain heart infusion medium supplemented with 2% yeast extract (BHIS; Becton, Dickinson, and Company) or Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB; Difco) supplemented with 2 μg/ml thiamphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5 μg/ml LL-37 (Anaspec), 0.125 – 0.15 μg/ml teicoplanin (Cayman Chemical Company), 0.75 – 1.0 μg/ml vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 60 μg/ml cefoperazone (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.5–10 μg/ml nisin (MP Biomedicals), as indicated.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Plasmid or Strain | Relevant genotype or features | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| HB101 | F− mcrB mrr hsdS20(rB− mB−) recA13 leuB6 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 rpsL20 | B. Dupuy |

| MC277 | HB101 pRK24 pMC211 | (42) |

| MC901 | HB101 pRK24 pMC632 | This study |

| MC1038 | HB101 pRK24 pMC687 | This study |

| C. difficile | ||

| 630 | Clinical isolate | (53) |

| 630Δerm | ErmS derivative of strain 630 | (54) |

| MC1040 | 630Δerm pMC687 | This study |

| MC1041 | 630Δerm Δskin (ΔvanZ1) | This study |

| MC282 | 630Δerm pMC211 | (42) |

| MC907 | 630Δerm pMC632 | This study |

| MC1260 | Δskin (ΔvanZ1) pMC211 | This study |

| MC1261 | Δskin (ΔvanZ1) pMC632 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK24 | Tra+, Mob+; bla, tet | (55) |

| pMC123 | E. coli-C. difficile shuttle vector; bla, catP | (37) |

| pMC211 | pMC123 PcprA | (42) |

| pMC632 | pMC211 PcprA::vanZ1 | This study |

| pMC687 | pMC211 PcprA::CD1234 | This study |

Strain and plasmid construction

Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2. Primer design was based on C. difficile strain 630 (GenBank accession NC_009089.1), and genomic DNA from strain 630Δerm served as template for all PCR amplification reactions. For PCR verification of the skin element, DNA for the control strain (skin+) was obtained from 630Δerm grown in BHIS supplemented with 0.5% fructose to prevent sporulation and skin excision. PCR and molecular biology techniques were performed using standard protocols (34–36). For construction of plasmid pMC684, the CD630_12340 coding sequence was amplified using primers oMC1609 and oMC1610, and cloned into the BamHI/XhoI sites of plasmid pMC211 to express CD630_12340 from the nisin-inducible cprA promoter (37–39). To construct plasmid pMC632, the CD630_12400 coding sequence was amplified using primers oMC1397 and oMC1398, and ligated into pMC211 at the BamHI/PstI sites to express CD630_12400 from the nisin-inducible cprA promoter (37–39). Plasmid sequences were confirmed by standard sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon).

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides

| Primer | Sequencea | Use |

|---|---|---|

| oMC44 | CTAGCTGCTCCTATGTCTCACATC | rpoC qPCR (37) |

| oMC45 | CCAGTCTCTCCTGGATCAACTA | rpoC qPCR (37) |

| oMC1393 | TGAAACCATGAATCTTAGAAGCATAAAC | vanZ1 (CD1240) qPCR |

| oMC1394 | CACATATATCCCAAATGGTACAAATATAGC | vanZ1 (CD1240) qPCR |

| oMC1397 | GCCATGGATCCAGTAAGGAGGTAATAAATGAAATCTAG | vanZ1 (CD1240) cloning |

| oMC1398 | GATGCCTGCAGCTTACGTTCTATTTTAAGCTAAAC | vanZ1 (CD1240) cloning |

| oMC1609 | GTGGGATCCTAAGTATAAGACAAGTTTATGAGTTC | CD1234 cloning |

| oMC1610 | CACTGCAGGCAACTTCTCTATTCTCTTAAC | CD1234 cloning |

| QRTBD326 | TCATCAAGAACATAGTTAGCCTCTG | screen for skin element excision (32) |

| IMV833 | TTCAACGGAAGATCAGGATG | screen for skin element excision (32) |

Sequences are written 5′ to 3′. Underlines indicate restriction enzyme sites used for cloning.

To transfer plasmids to C. difficile, plasmids were first introduced into E. coli strain HB101 pRK24, then conjugated to C. difficile. Transconjugants were isolated as previously described and verified by PCR (38, 40).

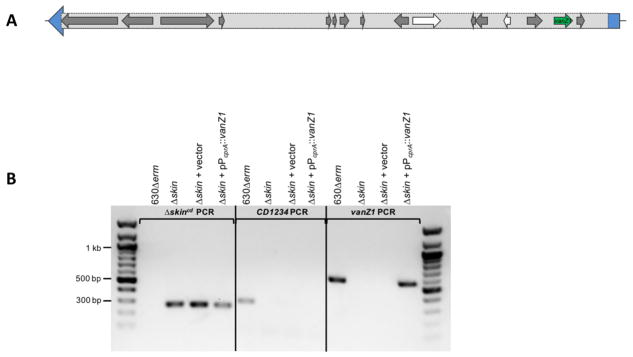

For deletion of the vanZ1 (CD1240) gene, we took advantage of the location of this gene within the skin element of sigK. The skin recombinase, CD1234, excises this element from the chromosome during sporulation (32). To excise the skin element, transcription of CD1234 was put under control of the nisin-inducible PcprA promoter (pMC687). This construct was used to induce expression of CD1234 and cause excision of the skin element in non-sporulating cells. The resulting clones were screened for successful excision of the skin element using primers flanking this region, and subsequently passaged without thiamphenicol to allow the loss of pMC687.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentration determination (MIC)

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined as previously described (41). Briefly, C. difficile cultures were grown in Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) to an OD600 of 0.45, diluted 1:10, and seeded at a further 1:10 dilution (for a starting inoculum of ~5 × 105 CFU/ml) into round-bottom 96-well plates prepared with serial dilutions of antimicrobials. For MICs with strains containing plasmids, 2 μg/ml thiamphenicol (to maintain plasmids) and 0.5 μg/ml nisin (to induce expression) was included. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of antimicrobial at which no growth was visible after 24 hours of anaerobic incubation at 37°C. Assays were performed a minimum of three times.

Phase contrast microscopy

Active cultures of C. difficile grown in BHIS were back-diluted to a starting OD600 of 0.03–0.05 in BHIS or BHIS supplemented with antimicrobials as indicated, and grown to OD600 of approximately 0.50. One milliliter of culture was collected, pelleted, and 2 μl placed on a microscope slide prepared with a 0.7% agarose pad and visualized using a X100 Ph3 oil immersion objective on a Nikon Eclipse Ci-L microscope, as previously detailed (42). A DS-Fi2 camera was used to acquire multiple fields of view for three biological replicates of each strain and condition examined.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis (qRT-PCR)

Active cultures of C. difficile grown in BHIS were back diluted to a starting OD600 of 0.03–0.05 in BHIS or BHIS supplemented with 0.125 μg/ml teicoplanin, 0.75 μg/ml vancomycin, 60 μg/ml cefoperazone, 2 μg/ml LL-37, or 10 μg/ml nisin. These concentrations were empirically determined in rich BHIS medium to be high enough to impact growth, while remaining sub-inhibitory. Once grown to an OD600 of 0.50, 3 ml of culture was harvested into 1:1 ethanol:acetone and stored at −80°C until use. RNA extraction, DNase I treatment, generation of cDNA, and qRT-PCR reactions were performed as previously described (42, 43) using the primers listed in Table 2. Each qRT-PCR reaction was performed as technical triplicates on at least three biological replicates. Normalization was performed using the ΔΔCt method, with normalization to rpoC expression levels (44).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s or Sidak’s multiple-comparison tests were used, as indicated.

RESULTS

Identification of VanZ orthologs in C. difficile

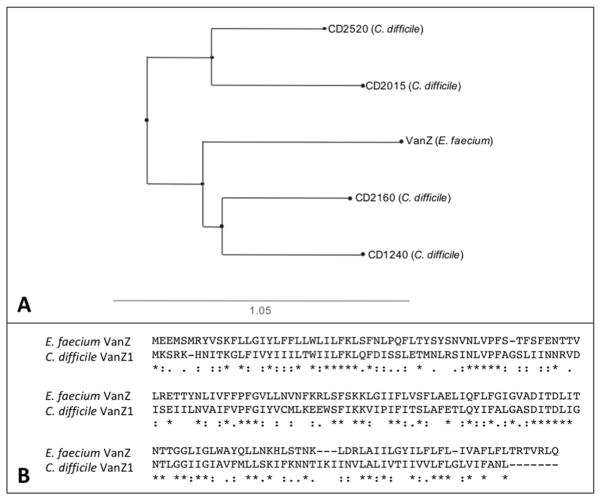

VanZ was originally identified in Enterococcus faecium, wherein it contributes to resistance to the glycopeptide antibiotic teicoplanin, but does not impact resistance to the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin (27). Protein BLAST analysis of the C. difficile strain 630 genome uncovered four putative VanZ orthologs: CD1240, CD2520, CD2015 and CD2160 (Fig 1A). CD1240 most closely aligns with VanZ relative to the other putative orthologs, sharing 38% identity and 60% similarity with E. faecium VanZ (Fig. 1B). An additional BLASTp analysis of all sequenced C. difficile genomes revealed widespread distribution of CD1240, which is localized within the skin element of the sporulation sigma factor, sigK (Fig. 2A). In a separate study investigating the transcriptional response of C. difficile to various antimicrobials, we also determined that CD1240 was induced over 25-fold in response to the host antimicrobial LL-37 (45). Based on the sequence similarity and the induction of CD1240 transcription by LL-37, we hypothesized that CD1240 could play a similar role to the E. faecium VanZ and may contribute to resistance against cell surface-acting antimicrobials, potentially impacting host resistance or therapeutic treatments.

Figure 1. Alignment of VanZ-family proteins.

A) Unrooted phylogenetic tree relating the VanZ of E. faecium to CD1240 (VanZ1) and three additional VanZ-like proteins (CD2015, CD2520 and CD2160) was created using Phylo.io version 1.0k (http://phylo.io/)(51). B) Protein sequences for C. difficile VanZ1 (CD1240, WP_009889012.1) and E. faecium VanZ (YP_006374628.1) were aligned using MAFFT version 7.388 (52). An asterisk below the sequence indicates identical residues, colons indicate similar residues, and dots indicate low similarity.

Figure 2. vanZ1 genetic context and deletion of the skincd element (Δskin mutant).

A) Graphical representation of the vanZ1 gene (green), within the sigK skincd element of strain 630Δerm. sigK (CD1230) is depicted in blue, with the skincd element delineated in the light gray box. Additional annotated skincd genes are depicted in grey, and pseudogenes are shown in white. B) Confirmation of skincd deletion and complementation. PCR products were generated using primers flanking the excised skincd element (280 bp, primers QRTBD326/IMV833), CD1234 (300 bp, primers oMC1609/oMC1610), or vanZ1 (564 bp, primers oMC1397/oMC1398). Genomic DNA from 630Δerm (control), Δskin (MC1041), Δskin + vector control (MC1260), or Δskin + pPcprA::vanZ1 (MC1261) were used as template.

VanZ has minimal impact on the growth of C. difficile in cell surface-acting antimicrobials

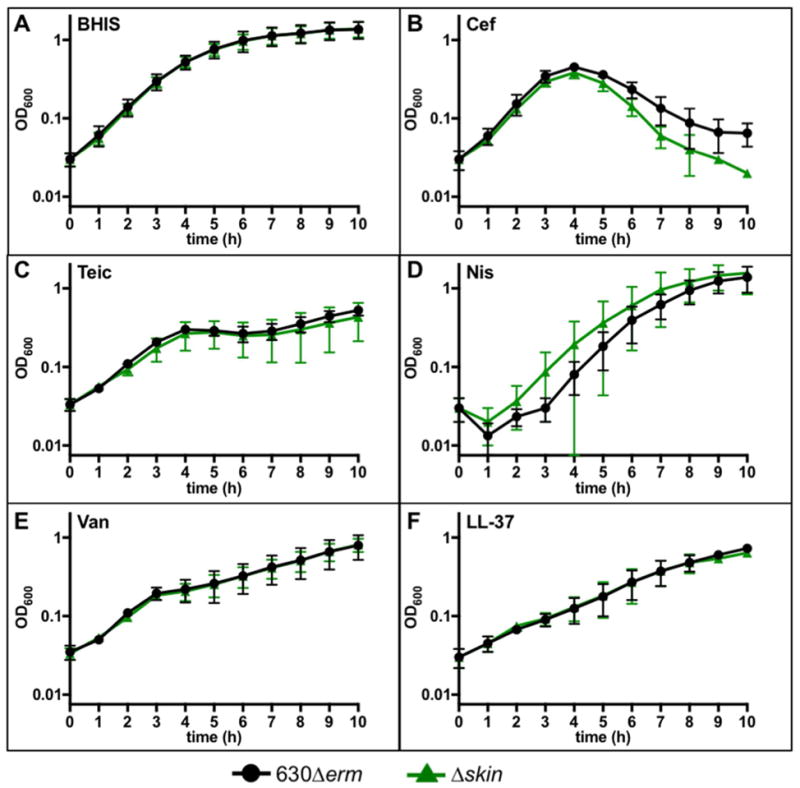

To test the hypothesis that CD1240 contributes to antimicrobial resistance, we excised the skincd element to create a CD1240 deletion mutant (Δskin; Fig. 2B) and examined the growth of the mutant in the presence of antimicrobials at sub-MIC concentrations (Fig. 3). The Δskin mutant demonstrated variable growth in teicoplanin (Fig. 3C), sometimes growing similarly to the parent strain and sometimes growing markedly less well. Similar results were obtained for teicoplanin when cells were grown in BHIS (not shown). The Δskin mutant had a modest deficiency for growth in cefoperazone (Fig. 3B) and slightly better growth than the parent strain in nisin (Fig. 3D). Although we were able to observe these trends, none of these differences were statistically significant, likely due to the highly variable nature of these phenotypes. No apparent differences in growth were observed in vancomycin, LL-37, or in rich medium alone (Fig. 3A, E, F).

Figure 3. Growth of the Δskin mutant in cell surface-acting antimicrobials.

Active cultures of strains 630Δerm and Δskin (MC1041) were diluted in A) BHIS, or BHIS supplemented with B) 60 μg/ml cefoperazone, C) 0.15 μg/ml teicoplanin, D) 10 μg/ml nisin, E) 1 μg/ml vancomycin, or F) 2.5 μg/ml LL-37. Graphs represent the mean OD600 readings from three independent replicates with error bars showing the standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test comparing 630Δerm to Δskin at each time point with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple tests. No statistically significant differences were observed for growth in any antibiotic at any time point.

To further assess the resistance and susceptibility of the Δskin mutant, minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays were performed with the aforementioned surface-acting antimicrobials. As detailed in Table 3, the Δskin mutant had a consistently two-fold lower MIC than the parent strain in teicoplanin (0.1 μg/ml in vanZ1 vs. 0.2 μg/ml in 630Δerm). Otherwise, the Δskin mutant demonstrated similar resistance profiles as the parent strain for all of the other antimicrobials tested.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 630Δerm and Δskin.

MIC values are reported in μg/ml. MICs were determined as described in Methods for vancomycin (Van), teicoplanin (Teic), LL-37, cefoperazone (Cef), and nisin (Nis). Values were obtained from three independent replicates, and results were consistent across replicates.

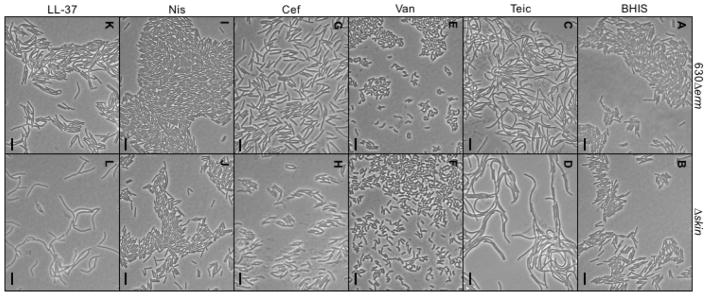

Analysis of cell morphology for the Δskin mutant and parent strain during growth revealed similar morphological phenotypes under all of the conditions tested, suggesting that deletion of VanZ1 does not result in apparent changes in gross morphology (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Deletion of vanZ1 does not alter gross cell morphology.

Phase contrast micrographs of strain 630Δerm (A, C, E, G, I, K) and Δskin (B, D, F, H, J, L) grown to mid-log phase in BHIS alone (A, B), 0.125 μg/ml teicoplanin (Teic; C, D), 1.0 μg/ml vancomycin (Van; E, F), 60 μg/ml cefoperazone (Cef; G, H), 10 μg/ml nisin (Nis; I, J), or 2.5 μg/ml LL-37 (K, L) are shown. Scale bars indicate 10 μm.

Effects of antimicrobials on vanZ1 expression

As previously stated, our preliminary studies suggested that vanZ1 expression was inducible by the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. To determine the impact of different antimicrobials on vanZ1 transcription, we performed transcriptional analysis by qRT-PCR to assess vanZ1 expression in the 630Δerm strain during growth in teicoplanin, cefoperazone, nisin, vancomycin, and LL-37 (Table 4). In confirmation of previous results, expression of vanZ1 was substantially induced during growth in LL-37 (~37-fold increase). Despite induction of vanZ1 expression in LL-37, the teicoplanin MIC of 630Δerm remained unchanged whether or not LL-37 was present (Supl. Table 1). Unexpectedly, small but statistically significant decreases in vanZ1 expression were observed during growth in vancomycin and cefoperazone. No change in vanZ1 expression occurred in teicoplanin or nisin.

Table 4.

vanZ1 expression in antimicrobials.

| Antimicrobial | Relative vanZ1 expressiona |

|---|---|

| Vanb | 0.64 ± 0.03 |

| Teic | 0.71 ± 0.10 |

| LL-37 | 36.9 ± 6.0 |

| Cef | 0.60 ± 0.14 |

| Nis | 0.85 ± 0.08 |

Expression of vanZ1 in 630Δerm was determined by qRT-PCR as described in Methods. Values are normalized to expression without any antimicrobial added. Values shown are the mean from three independent replicates ± the standard error of the mean. Expression levels in antimicrobials were compared the the expression level without antimicrobial by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. Bold values indicate adjusted P-value < 0.05.

Concentrations of antimicrobials used: vancomycin (Van) 0.75 μg/ml, teicoplanin (Teic) 0.125 μg/ml, LL-37 2 μg/ml, cefoperazone (Cef) 60 μg/ml, nisin (Nis) 10 μg/ml.

Expression of vanZ1 in the Δskin mutant restores growth in teicoplanin

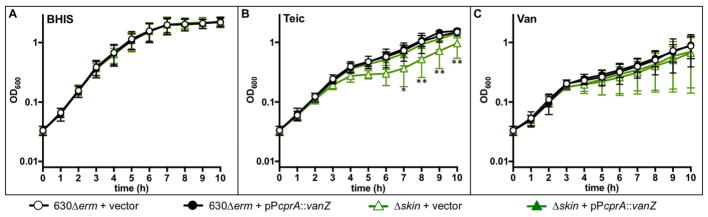

To further examine the impact of vanZ1 expression and to complement the Δskin mutant, a plasmid containing vanZ1 under the control of an inducible promoter was conjugated into the Δskin strain (Fig. 2B). In addition, this plasmid was used to induce expression of vanZ1 in the parent strain to determine the potential impact of vanZ1 overexpression on antimicrobial resistance. Strains expressing inducible, plasmid-encoded vanZ1 or empty vector controls, were assessed for growth with and without the addition of antimicrobials to the medium. All strains grew similarly in rich medium and in medium containing vancomycin (Fig. 5). Overexpression of exogenous vanZ1 in 630Δerm did not affect growth in teicoplanin. However, the Δskin strain expressing exogenous vanZ1 adapted and grew more quickly in teicoplanin relative to the Δskin strain carrying only the empty control vector (Fig. 5B; Fig. S1). Therefore, VanZ1 is sufficient to restore the growth of the Δskin mutant in teicoplanin. This finding indicates that vanZ1, and not other genes in the skin element, accounts for the growth defect in teicoplanin seen in the Δskin mutant

Figure 5. Addition of vanZ1 restores growth of the Δskin mutant in teicoplanin.

Active cultures of strains 630Δerm pMC211 (vector control, MC282), 630Δerm pMC632 (pPcprA::vanZ1, MC907), Δskin + pMC211 (vector control, MC1260), and Δskin pMC632 (pPcprA::vanZ1, MC1261) were diluted in A) BHIS, or with supplementation with B) 0.15 μg/ml teicoplanin, or C) 1.0 μg/ml vancomycin. All cultures also contained 2 μg/ml thiamphenicol to maintain the plasmid and 0.5 μg/ml nisin to induce expression from PcprA. Graphs represent the mean OD600 readings from three independent replicates (Figure S1) with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, comparing to 630Δerm vector control at the same time point. * indicates adjusted P-value < 0.05, ** indicates ≤ 0.001.

In addition, the MICs of these strains were assessed in the same antimicrobials used for analysis of the Δskin mutant (except nisin, due to the nisin-dependent expression system present) (Supplemental Table 2). The MIC values for the vector control strains differ slightly from the MIC values that were observed with the parent strains (Table 3). These differences may be attributed to the addition of thiamphenicol and nisin and the presence of plasmids in these strains. We did not observe any differences in MIC values for any of the strains grown with any of the antimicrobials, indicating that neither overexpression of vanZ1 in 630Δerm nor restoration of vanZ1 in the Δskin mutant is sufficient to increase resistance to teicoplanin, vancomycin, LL-37, or cefoperazone.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have characterized a predicted vanZ gene, CD1240, of C. difficile and assessed its contribution to antimicrobial resistance. The data demonstrate that vanZ1 deletion modestly impacts teicoplanin resistance, but does not significantly impact resistance to vancomycin or other cell surface-acting antimicrobials tested (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the C. difficile VanZ1 likely has a similar function to the VanZ of E. faecium (Fig. 1) (27).

Although the function of the E. faecium and C. difficile VanZ orthologs appear similar, the regulation and genomic context of these orthologs are quite different. In E. faecium and other vanZ-encoding species, the vanZ gene is located within the vanA gene cluster, which is regulated by the adjacent VanRS two-component system in response to glycopeptide exposure (8). In C. difficile, vanZ1 is not encoded within a VanA operon or near any other apparent vancomycin resistance genes. Further, vanZ1 is not expressed in response to glycopeptide antibiotics, but it instead is induced by the host antimicrobial peptide, LL-37 (Fig. 2 and Table 4).

Curiously, the vanZ1 gene is encoded within the skincd element of the sigK coding sequence, which is spliced to generate the mature sigK transcript during sporulation. As a result, the vanZ1 gene is excised from the DNA within the mother cell compartment during the late stages of sporulation, although it remains in the forespore to ensure survival of the gene in future daughter cells (32, 46). Previous studies have shown that vanZ1 is expressed during C. difficile sporulation and it is dependent on the master regulator of sporulation, Spo0A, for transcription (32, 47, 48). Though the skincd (vanZ1) mutant forms fully mature spores, the spore structure of the skincd mutant contained less compact electron-dense layers around the spore coat and was visually disorganized relative to wild-type spores (32). However, it is not clear whether this spore disorganization results from the absence of genes within the skincd element (such as vanZ1), is a consequence of early SigK activation in a skincd-deficient strain, or both. Unfortunately, the large size and dynamic processing of the skincd element precludes complementation with the entire skincd sequence, limiting complementation to genes within the element (32).

Deletion of the skin element had a two-fold effect on the teicoplanin concentration required for growth inhibition (Table 3), and we found that induction of plasmid-encoded vanZ1 expression in the Δskin mutant restored growth to the wild-type teicoplanin phenotype (Fig. 5). The similarity of the C. difficile VanZ1 to VanZ of E. faecalis, combined with their shared ability to confer teicoplanin resistance, suggests that these proteins function similarly. However, the specific function of VanZ has not been determined for E. faecium or for any other species that encode this factor. Analysis of the C. difficile VanZ1 and E. faecium VanZ predicted topologies suggests that both are membrane proteins containing five predicted transmembrane helices, but no enzymatic domains are apparent (TMpred; BLASTp). Phenotypic examination of the gross cellular morphology of the Δskin mutant did not uncover differences in cell shape, size, or apparent structure (Fig. 4), suggesting that VanZ1 is not a fundamental factor in the synthesis or turnover of the C. difficile cell wall during vegetative cell growth. The Δskin mutant demonstrates altered sensitivity to teicoplanin, nisin, and cefoperazone, which target lipid II and peptidoglycan crosslinks, respectively, but not to LL-37, which targets the membrane. (Fig. 3). This phenotype is consistent with resistance mechanisms that generate cell-surface modifications and broadly prevent association of antimicrobials with their cell-surface targets (49).

Similar to the E. faecium VanZ, the C. difficile VanZ1 ortholog contributes to the ability of the organism to grow in the presence of teicoplanin (27). Teicoplanin, though not approved for use in the US, is used as a treatment for CDI in Europe. A recent study found that teicoplanin may be the preferred choice for patients with severe CDI, because patients treated with teicoplanin had significantly lower recurrence rates than those treated with vancomycin (5, 50). As the use of teicoplanin as a treatment for CDI increases, care should be taken to consider the intrinsic sub-clinical teicoplanin resistance conferred by vanZ1 and the potential for selection of increased VanZ1 production as a mechanism of resistance. Additional characterization of VanZ1 function, as well as examination of other vanZ-like genes in C. difficile is needed to determine the potential for these factors to impact antimicrobial resistance.

Supplementary Material

C. difficile encodes a conserved ortholog of VanZ from E. faecium

vanZ1 is induced by the host antimicrobial, LL-37, but not by teicoplanin

VanZ1 confers low-level resistance to teicoplanin, but not to LL-37

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the McBride lab for their feedback on this manuscript. The U.S. National Institutes of Health through research grants DK087763, DK101870, AI109526, and AI121684 to SMM, and GM008169 to ECW supported this work. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CDI

C. difficile infection

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- skin element

sigma K intervening element

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Asha NJ, Tompkins D, Wilcox MH. Comparative analysis of prevalence, risk factors, and molecular epidemiology of antibiotic-associated diarrhea due to Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2785–2791. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ European Society of Clinical M, Infectious D. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 2):1–26. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile in adults: Treatment 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tannock GW, Munro K, Taylor C, Lawley B, Young W, Byrne B, Emery J, Louie T. A new macrocyclic antibiotic, fidaxomicin (OPT-80), causes less alteration to the bowel microbiota of Clostridium difficile-infected patients than does vancomycin. Microbiology. 2010;156:3354–3359. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davido B, Leplay C, Bouchand F, Dinh A, Villart M, Le Quintrec JL, Teillet L, Salomon J, Michelon H. Oral Teicoplanin as an Alternative First-Line Regimen in Clostridium difficile Infection in Elderly Patients: A Case Series. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37:699–703. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng Z, Jin D, Kim HB, Stratton CW, Wu B, Tang YW, Sun X. Update on Antimicrobial Resistance in Clostridium difficile: Resistance Mechanisms and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1998–2008. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02250-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman J, Vernon J, Pilling S, Morris K, Nicholson S, Shearman S, Longshaw C, Wilcox MH. The ClosER study: results from a three-year pan-European longitudinal surveillance of antibiotic resistance among prevalent Clostridium difficile ribotypes, 2011–2014. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pootoolal JN, Wright JGD. Glycopeptide antibiotic resistance Annual Review Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2002;42:381–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091601.142813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courvalin P. Genetics of glycopeptide resistance in Gram-positive pathogens. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;294:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(Suppl 1):S25–34. doi: 10.1086/491711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugg TD, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh CT. Identification of vancomycin resistance protein VanA as a D-alanine:D-alanine ligase of altered substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2017–2021. doi: 10.1021/bi00222a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Quantitative analysis of the metabolism of soluble cytoplasmic peptidoglycan precursors of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:33–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casadewall B, Courvalin P. Characterization of the vanD glycopeptide resistance gene cluster from Enterococcus faecium BM4339. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3644–3648. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3644-3648.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Lin D, Yan G, Ye X, Wu S, Guo Y, Zhu D, Hu F, Zhang Y, Wang F, Jacoby GA, Wang M. vanM, a new glycopeptide resistance gene cluster found in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4643–4647. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01710-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraimow H, Knob C, Herrero IA, Patel R. Putative VanRS-like two-component regulatory system associated with the inducible glycopeptide resistance cluster of Paenibacillus popilliae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2625–2633. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2625-2633.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arias CA, Courvalin P, Reynolds PE. vanC cluster of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1660–1666. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1660-1666.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abadia Patino L, Courvalin P, Perichon B. vanE gene cluster of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6457–6464. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6457-6464.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Depardieu F, Bonora MG, Reynolds PE, Courvalin P. The vanG glycopeptide resistance operon from Enterococcus faecalis revisited. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:931–948. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd DA, Willey BM, Fawcett D, Gillani N, Mulvey MR. Molecular characterization of Enterococcus faecalis N06–0364 with low-level vancomycin resistance harboring a novel D-Ala-D-Ser gene cluster, vanL. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2667–2672. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01516-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bugg TD, Wright GD, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh CT. Molecular basis for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147: biosynthesis of a depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursor by vancomycin resistance proteins VanH and VanA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10408–10415. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billot-Klein D, Blanot D, Gutmann L, van Heijenoort J. Association constants for the binding of vancomycin and teicoplanin to N-acetyl-D-alanyl-D-alanine and N-acetyl-D-alanyl-D-serine. Biochem J. 1994;304(Pt 3):1021–1022. doi: 10.1042/bj3041021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Depardieu F, Reynolds PE, Courvalin P. VanD-type vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium 10/96A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:7–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.7-18.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arthur M, Molinas C, Courvalin P. The VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2582–2591. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2582-2591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bugg TD, Walsh CT. Intracellular steps of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan biosynthesis: enzymology, antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance. Nat Prod Rep. 1992;9:199–215. doi: 10.1039/np9920900199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds PE, Depardieu F, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance mediated by enterococcal transposon Tn1546 requires production of VanX for hydrolysis of D-alanyl-D-alanine. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1065–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright GD, Molinas C, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh CT. Characterization of vanY, a DD-carboxypeptidase from vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium BM4147. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1514–1518. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Molinas C, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. The vanZ gene of Tn1546 from Enterococcus faecium BM4147 confers resistance to teicoplanin. Gene. 1995;154:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00851-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sebaihia M, Wren BW, Mullany P, Fairweather NF, Minton N, Stabler R, Thomson NR, Roberts AP, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Wang H, Holden MT, Wright A, Churcher C, Quail MA, Baker S, Bason N, Brooks K, Chillingworth T, Cronin A, Davis P, Dowd L, Fraser A, Feltwell T, Hance Z, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Moule S, Mungall K, Price C, Rabbinowitsch E, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Stevens K, Unwin L, Whithead S, Dupuy B, Dougan G, Barrell B, Parkhill J. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:779–786. doi: 10.1038/ng1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peltier J, Courtin P, El Meouche I, Catel-Ferreira M, Chapot-Chartier MP, Lemee L, Pons JL. Genomic and expression analysis of the vanG-like gene cluster of Clostridium difficile. Microbiology. 2013;159:1510–1520. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.065060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ammam F, Marvaud JC, Lambert T. Distribution of the vanG-like gene cluster in Clostridium difficile clinical isolates. Can J Microbiol. 2012;58:547–551. doi: 10.1139/w2012-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ammam F, Meziane-Cherif D, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Blanot D, Patin D, Boneca IG, Courvalin P, Lambert T, Candela T. The functional vanGCd cluster of Clostridium difficile does not confer vancomycin resistance. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:612–625. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serrano M, Kint N, Pereira FC, Saujet L, Boudry P, Dupuy B, Henriques AO, Martin-Verstraete I. A Recombination Directionality Factor Controls the Cell Type-Specific Activation of sigmaK and the Fidelity of Spore Development in Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luria SE, Burrous JW. Hybridization between Escherichia coli and Shigella. J Bacteriol. 1957;74:461–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.74.4.461-476.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards AN, Suarez JM, McBride SM. Culturing and maintaining Clostridium difficile in an anaerobic environment. J Vis Exp. 2013 doi: 10.3791/50787:e50787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouillaut L, McBride SM, Sorg JA. Genetic manipulation of Clostridium difficile. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2011;Chapter 9(Unit 9A):2. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc09a02s20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorg JA, Dineen SS. Laboratory maintenance of Clostridium difficile. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2009;Chapter 9(Unit9A):1. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc09a01s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBride SM, Sonenshein AL. Identification of a genetic locus responsible for antimicrobial peptide resistance in Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 2011;79:167–176. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00731-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purcell EB, McKee RW, McBride SM, Waters CM, Tamayo R. Cyclic diguanylate inversely regulates motility and aggregation in Clostridium difficile. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/JB.00100-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suarez JM, Edwards AN, McBride SM. The Clostridium difficile cpr locus is regulated by a noncontiguous two-component system in response to type A and B lantibiotics. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:2621–2631. doi: 10.1128/JB.00166-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McBride SM, Sonenshein AL. The dlt operon confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides in Clostridium difficile. Microbiology. 2011;157:1457–1465. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.045997-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu R, Suarez JM, Weisblum B, Gellman SH, McBride SM. Synthetic Polymers Active against Clostridium difficile Vegetative Cell Growth and Spore Outgrowth. J Am Chem Soc. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ja506798e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards AN, Nawrocki KL, McBride SM. Conserved oligopeptide permeases modulate sporulation initiation in Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4276–4291. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02323-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dineen SS, McBride SM, Sonenshein AL. Integration of metabolism and virulence by Clostridium difficile CodY. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5350–5362. doi: 10.1128/JB.00341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woods EC, Edwards AN, McBride SM. The C. difficile clnRAB operon initiates adaptations to the host environment in response to LL-37. 2018 doi: 10.1101/347286. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haraldsen JD, Sonenshein AL. Efficient sporulation in Clostridium difficile requires disruption of the sigmaK gene. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:811–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paredes-Sabja D, Shen A, Sorg JA. Clostridium difficile spore biology: sporulation, germination, and spore structural proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fimlaid KA, Bond JP, Schutz KC, Putnam EE, Leung JM, Lawley TD, Shen A. Global Analysis of the Sporulation Pathway of Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nawrocki KL, Crispell EK, McBride SM. Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance Mechanisms of Gram-Positive Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel) 2014;3:461–492. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics3040461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Popovic N, Korac M, Nesic Z, Milosevic B, Urosevic A, Jevtovic D, Mitrovic N, Markovic A, Jordovic J, Katanic N, Barac A, Milosevic I. Oral teicoplanin versus oral vancomycin for the treatment of severe Clostridium difficile infection: a prospective observational study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson O, Dylus D, Dessimoz C. Phylo.io: Interactive Viewing and Comparison of Large Phylogenetic Trees on the Web. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:2163–2166. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wust J, Hardegger U. Transferable resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23:784–786. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.5.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hussain HA, Roberts AP, Mullany P. Generation of an erythromycin-sensitive derivative of Clostridium difficile strain 630 (630Δerm) and demonstration that the conjugative transposon Tn916ΔE enters the genome of this strain at multiple sites. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2005;54:137–141. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas CM, Smith CA. Incompatibility group P plasmids: genetics, evolution, and use in genetic manipulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:77–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.